Adolf Eichmann | |

|---|---|

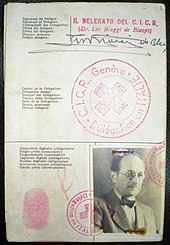

Eichmann in 1942 | |

| Born | Otto Adolf Eichmann 19 March 1906 |

| Died | 1 June 1962 (aged 56) Ayalon Prison, Ramla, Israel |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality |

|

| Other names |

|

| Organization | |

| Spouse | Veronika Liebl (m. 1935) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Awards |

|

| Allegiance | |

| Conviction(s) |

|

Date apprehended | 11 May 1960 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Signature | |

Otto Adolf Eichmann (/ˈaɪkmən/ EYEKH-mən, German: [ˈɔtoː ˈʔaːdɔlf ˈʔaɪçman]; 19 March 1906 – 1 June 1962) was a German-Austrian official of the Nazi Party, an officer of the Schutzstaffel (SS), and one of the major organisers of the Holocaust. He participated in the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, at which the implementation of the genocidal Final Solution to the Jewish Question was planned. Following this, he was tasked by SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich with facilitating and managing the logistics involved in the mass deportation of millions of Jews to Nazi ghettos and Nazi extermination camps across German-occupied Europe. He was captured and detained by the Allies in 1945, but escaped and eventually settled in Argentina. In May 1960, he was abducted by Mossad, the national intelligence agency of Israel. Eichmann subsequently stood trial with the Supreme Court of Israel. The highly publicised Eichmann trial resulted in his conviction in Jerusalem, following which he was executed by hanging in 1962.

After doing poorly in school, Eichmann briefly worked for his father's mining company in Austria, where the family had moved in 1914. He worked as a travelling oil salesman beginning in 1927, and joined both the Nazi Party and the SS in 1932. He returned to Germany in 1933, where he joined the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, "Security Service"); there he was appointed head of the department responsible for Jewish affairs – especially emigration, which the Nazis encouraged through violence and economic pressure. After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Eichmann and his staff arranged for Jews to be concentrated in ghettos in major cities with the expectation that they would be transported either farther east or overseas. He also drew up plans for a Jewish reservation, first at Nisko in southeast Poland and later in Madagascar, but neither of these plans was carried out.

The Nazis began the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, and their Jewish policy changed from coerced emigration to extermination. To coordinate planning for the genocide, Reinhard Heydrich, who was Eichmann's superior, hosted the regime's administrative leaders at the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942. Eichmann collected information for him, attended the conference, and prepared the minutes. Eichmann and his staff became responsible for Jewish deportations to extermination camps, where the victims were gassed. Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944, and Eichmann oversaw the deportation of much of the Jewish population. Most of the victims were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp, where about 75 per cent were murdered upon arrival. By the time the transports were stopped in July 1944, 437,000 of Hungary's 725,000 Jews had been killed. Dieter Wisliceny testified at Nuremberg that Eichmann told him he would "leap laughing into the grave because the feeling that he had five million people on his conscience would be for him a source of extraordinary satisfaction."

After Germany's defeat in 1945, Eichmann was captured by US forces, but escaped from a detention camp and moved around Germany to avoid re-capture. He ended up in a small village in Lower Saxony, where he lived until 1950, when he moved to Argentina using false papers he obtained with help from an organisation directed by Catholic bishop Alois Hudal. Information collected by Mossad, Israel's intelligence agency, confirmed his location in 1960. A team of Mossad and Shin Bet agents captured Eichmann and brought him to Israel to stand trial on 15 criminal charges, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against the Jewish people. During the trial, he did not deny the Holocaust or his role in organising it, but said he was simply following orders in a totalitarian Führerprinzip system. He was found guilty on all of the charges, and was executed by hanging on 1 June 1962.[c] The trial was widely followed in the media and was later the subject of several books, including Hannah Arendt's Eichmann in Jerusalem, in which Arendt coined the phrase "the banality of evil" to describe Eichmann.

Early life and education

Otto Adolf Eichmann, the eldest of five children, was born in 1906 to a Calvinist Protestant family in Solingen, Germany. His parents were Adolf Karl Eichmann, a bookkeeper, and Maria (née Schefferling), a housewife. The elder Adolf moved to Linz, Austria, in 1913 to take a position as commercial manager for the Linz Tramway and Electrical Company, and the rest of the family followed a year later. After the death of Maria in 1916, Eichmann's father married Maria Zawrzel, a devout Protestant with two sons.

Eichmann attended the Kaiser Franz Joseph Staatsoberrealschule (state secondary school) in Linz, the same high school Adolf Hitler had attended 17 years before. He played the violin and participated in sports and clubs, including a Wandervogel woodcraft and scouting group that included some older boys who were members of various right-wing militias. His poor school performance resulted in his father's withdrawing him from the Realschule and enrolling him in the Höhere Bundeslehranstalt für Elektrotechnik, Maschinenbau und Hochbau vocational college. He left without attaining a degree and joined his father's new enterprise, the Untersberg Mining Company, where he worked for several months. From 1925 to 1927 he worked as a sales clerk for the Oberösterreichische Elektrobau AG radio company. Next, between 1927 and early 1933, Eichmann worked in Upper Austria and Salzburg as district agent for the Vacuum Oil Company AG.

During this time, he joined the Jungfrontkämpfervereinigung, the youth section of Hermann Hiltl's right-wing veterans movement, and began reading newspapers published by the Nazi Party. The party platform included the dissolution of the Weimar Republic in Germany, rejection of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, radical antisemitism, and anti-Bolshevism. They promised a strong central government, increased Lebensraum (living space) for Germanic peoples, formation of a national community based on race, and racial cleansing via the active suppression of Jews, who would be stripped of their citizenship and civil rights.

Early career

On the advice of family friend and local SS leader Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Eichmann joined the Austrian branch of the Nazi Party on 1 April 1932, member number 889,895. His membership in the SS was confirmed seven months later (SS member number 45,326). His regiment was SS-Standarte 37, responsible for guarding the party headquarters in Linz and protecting party speakers at rallies, which would often become violent. Eichmann pursued party activities in Linz on weekends while continuing in his position at Vacuum Oil in Salzburg.

A few months after the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in January 1933, Eichmann lost his job due to staffing cutbacks at Vacuum Oil. The Nazi Party was banned in Austria around the same time. These events were factors in Eichmann's decision to return to Germany.

Like many other Nazis fleeing Austria in the spring of 1933, Eichmann left for Passau, where he joined Andreas Bolek at his headquarters. After he attended a training programme at the SS depot in Klosterlechfeld in August, Eichmann returned to the Passau border in September, where he was assigned to lead an eight-man SS liaison team to guide Austrian National Socialists into Germany and smuggle propaganda material from there into Austria. In late December, when this unit was dissolved, Eichmann was promoted to SS-Scharführer (squad leader, equivalent to corporal). Eichmann's battalion of the Deutschland Regiment was quartered at barracks next door to Dachau concentration camp.

By 1934, Eichmann requested transfer to the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) of the SS, to escape the "monotony" of military training and service at Dachau. Eichmann was accepted into the SD and assigned to the sub-office on Freemasons, organising seized ritual objects for a proposed museum and creating a card index of German Freemasons and Masonic organisations. He prepared an anti-Masonic exhibition, which proved to be extremely popular. Visitors included Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, Kaltenbrunner, and Baron Leopold von Mildenstein. Mildenstein invited Eichmann to join his Jewish Department, Section II/112 of the SD, at its Berlin headquarters. Eichmann's transfer was granted in November 1934. He later came to consider this as his big break. He was assigned to study and prepare reports on the Zionist movement and various Jewish organisations. He even learned a smattering of Hebrew and Yiddish, gaining a reputation as a specialist in Zionist and Jewish matters. On 21 March 1935 Eichmann married Veronika (Vera) Liebl (1909–93). The couple had four sons: Klaus (born 1936 in Berlin), Horst Adolf (born 1940 in Vienna), Dieter Helmut (born 1942 in Prague) and Ricardo Francisco (born 1955 in Buenos Aires). Eichmann was promoted to SS-Hauptscharführer (head squad leader) in 1936 and was commissioned as an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) the following year. Eichmann left the church in 1937.

Nazi Germany used violence and economic pressure to encourage Jews to leave Germany of their own volition; around 250,000 of the country's 437,000 Jews emigrated between 1933 and 1939. Eichmann travelled to British Mandatory Palestine with his superior Herbert Hagen in 1937 to assess the possibility of Germany's Jews voluntarily emigrating to that country, disembarking with forged press credentials at Haifa, whence they travelled to Cairo in Egypt. There they met Feival Polkes, an agent of the Haganah, with whom they were unable to strike a deal. Polkes suggested that more Jews should be allowed to leave under the terms of the Haavara Agreement, each being allowed to take £1000 with them so that they would qualify for entry to Palestine under a less restricted form of immigration. The suggestion was dismissed, Hagen giving two reasons in his report: a strong Jewish presence in Palestine might lead to their founding an independent state, which would run contrary to Reich policy; it was also against Reich policy to allow the free transferal of "Jewish capital". Eichmann and Hagen attempted to return to Palestine a few days later, but were denied entry after the British authorities refused them the required visas. Their report on their visit was published in 1982.

In 1938, Eichmann was posted to Vienna to help organise Jewish emigration from Austria, which had just been integrated into the Reich through the Anschluss. Jewish community organisations were placed under supervision of the SD and tasked with encouraging and facilitating Jewish emigration. Funding came from money seized from other Jewish people and organisations, as well as donations from overseas, which were placed under SD control. Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) in July 1938, and appointed to the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna, created in August in a room in the former Palais Albert Rothschild at Prinz-Eugen-Straße 20–22. By the time he left Vienna in May 1939, nearly 100,000 Jews had left Austria legally, and many more had been smuggled out to Palestine and elsewhere.

World War II

Policy transition from emigration to deportation

Within weeks of the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, Nazi policy toward the Jews changed from voluntary emigration to forced deportation. After discussions with Hitler in the preceding weeks, on 21 September SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the SD, advised his staff that Jews were to be collected into cities in Poland with good rail links to facilitate their expulsion from territories controlled by Germany, starting with areas that had been incorporated into the Reich. He announced plans to create a reservation in the General Government (the portion of Poland not incorporated into the Reich), where Jews and others deemed undesirable would await further deportation. On 27 September 1939 the SD and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo, "Security Police") – the latter comprising the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) and Kriminalpolizei (Kripo) police agencies – were combined into the new Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, "Reich Security Main Office"), which was placed under Heydrich's control.

After a posting in Prague to assist in setting up an emigration office there, Eichmann was transferred to Berlin in October 1939 to command the Reichszentrale für jüdische Auswanderung ("Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration") for the entire Reich under Heydrich and Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo. He was immediately assigned to organise the deportation of 70,000 to 80,000 Jews from Ostrava district in Moravia and Katowice district in the recently annexed portion of Poland. On his own initiative, Eichmann also laid plans to deport Jews from Vienna. Under the Nisko Plan, Eichmann chose Nisko as the location for a new transit camp where Jews would be temporarily housed before being deported elsewhere. In the last week of October 1939, 4,700 Jews were sent to the area by train and were essentially left to fend for themselves in an open meadow with no water and little food. Barracks were planned but never completed. Many of the deportees were driven by the SS into Soviet-occupied territory and others were eventually placed in a nearby labour camp. The operation soon was called off, partly because Hitler decided the required trains were better used for military purposes for the time being. Meanwhile, as part of Hitler's long-range resettlement plans, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were being transported into the annexed territories, and ethnic Poles and Jews were being moved further east, particularly into the General Government.

On 19 December 1939, Eichmann was assigned to head RSHA Referat IV D4 (RSHA Sub-Department IV-D4), tasked with overseeing Jewish affairs and evacuation. Heydrich announced Eichmann to be his "special expert", in charge of arranging for all deportations into occupied Poland. The job entailed co-ordinating with police agencies for the physical removal of the Jews, dealing with their confiscated property, and arranging financing and transport. Within a few days of his appointment, Eichmann formulated a plan to deport 600,000 Jews into the General Government. The plan was stymied by Hans Frank, governor-general of the occupied territories, who was disinclined to accept the deportees as to do so would have a negative impact on economic development and his ultimate goal of Germanisation of the region. In his role as minister responsible for the Four Year Plan, on 24 March 1940 Hermann Göring forbade any further transports into the General Government unless cleared first by himself or Frank. Transports continued, but at a much slower pace than originally envisioned. From the start of the war until April 1941, around 63,000 Jews were transported into the General Government. On many of the trains in this period, up to a third of the deportees died in transit. While Eichmann claimed at his trial to be upset by the appalling conditions on the trains and in the transit camps, his correspondence and documents of the period show that his primary concern was to achieve the deportations economically and with minimal disruption to Germany's ongoing military operations.

Jews were concentrated into ghettos in major cities with the expectation that at some point they would be transported farther east or even overseas. Horrendous conditions in the ghettos – severe overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of food – resulted in a high death rate. On 15 August 1940, Eichmann released a memorandum titled Reichssicherheitshauptamt: Madagaskar Projekt (Reich Security Main Office: Madagascar Project), calling for the resettlement to Madagascar of a million Jews per year for four years. When Germany failed to defeat the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain, the invasion of Britain was postponed indefinitely. As Britain still controlled the Atlantic and her merchant fleet would not be at Germany's disposal for use in evacuations, planning for the Madagascar proposal stalled. Hitler continued to mention the Plan until February 1942, when the idea was permanently shelved.

Wannsee Conference

From the start of the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Einsatzgruppen (task forces) followed the army into conquered areas and rounded up and killed Jews, Comintern officials, and ranking members of the Communist Party. Eichmann was one of the officials who received regular detailed reports of their activities. On 31 July, Göring gave Heydrich written authorisation to prepare and submit a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in all territories under German control and to co-ordinate the participation of all involved government organisations. The Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) called for deporting the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia, for use as slave labour or to be murdered.

Eichmann stated at his later interrogations that Heydrich told him in mid-September that Hitler had ordered that all Jews in German-controlled Europe were to be killed. "I never saw a written order," Eichmann said at his trial. "All I know is that Heydrich told me, 'the Führer ordered the physical extermination of the Jews.'" The initial plan was to implement Generalplan Ost after the conquest of the Soviet Union. However, with the entry of the United States into the war in December and the German failure in the Battle of Moscow, Hitler decided that the Jews of Europe were to be exterminated immediately rather than after the war, which now had no end in sight. Around this time, Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel), the highest rank he achieved.

To co-ordinate planning for the proposed genocide, Heydrich hosted the Wannsee Conference, which brought together administrative leaders of the Nazi regime on 20 January 1942. In preparation for the conference, Eichmann drafted for Heydrich a list of the numbers of Jews in various European countries and prepared statistics on emigration. Eichmann attended the conference, oversaw the stenographer who took the minutes, and prepared the official distributed record of the meeting. In his covering letter, Heydrich specified that Eichmann would act as his liaison with the departments involved. Under Eichmann's supervision, large-scale deportations began almost immediately to extermination camps at Bełżec, Sobibor, Treblinka and elsewhere. The genocide was code-named Operation Reinhard in honour of Heydrich, who had died in Prague in early June from wounds suffered in an assassination attempt. Kaltenbrunner succeeded Heydrich as head of the RSHA.

Eichmann did not make policy, but acted in an operational capacity. Specific deportation orders came from his RSHA superior, Gestapo chief Müller, acting on Himmler's behalf. Eichmann's office was responsible for collecting information on the Jews in each area, organising the seizure of their property, and arranging for and scheduling trains. His department was in constant contact with the Foreign Office, as Jews of conquered nations such as France could not as easily be stripped of their possessions and deported to their deaths. Eichmann held regular meetings in his Berlin offices with his department members working in the field and travelled extensively to visit concentration camps and ghettos. His wife, who disliked Berlin, resided in Prague with the children. Eichmann initially visited them weekly, but as time went on, his visits tapered off to once a month.

Occupation of Hungary

Germany invaded Hungary on 19 March 1944. Eichmann arrived the same day, and was soon joined by top members of his staff and five or six hundred members of the SD, SS, and SiPo. Hitler's appointment of a Hungarian government more amenable to the Nazis meant that the Hungarian Jews, who had remained essentially unharmed until that point, would now be deported to Auschwitz concentration camp to serve as forced labour or be gassed. Eichmann toured northeastern Hungary in the last week of April and visited Auschwitz in May to assess the preparations. During the Nuremberg Trials, Rudolf Höss, commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, testified that Himmler had told Höss to receive all operational instructions for the implementation of the Final Solution from Eichmann. Round-ups began on 16 April, and from 14 May, four trains of 3,000 Jews per day left Hungary and travelled to the camp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, arriving along a newly built spur line that terminated a few hundred metres away from the gas chambers. Between 10 and 25 per cent of the people on each train were chosen as forced labourers; the rest were killed within hours of arrival. Under international pressure, the Hungarian government halted deportations on 6 July 1944, by which time over 437,000 of Hungary's 725,000 Jews had died. In spite of the orders to stop, Eichmann personally made arrangements for additional trains of victims to be sent to Auschwitz on 17 and 19 July.

In a series of meetings beginning on 25 April, Eichmann met with Joel Brand, a Hungarian Jew and member of the Relief and Rescue Committee (RRC). Eichmann later testified that Berlin had authorised him to allow emigration of a million Jews in exchange for 10,000 trucks equipped to handle the wintry conditions on the Eastern Front. Nothing came of the proposal, as the Western Allies refused to consider the offer. In June 1944 Eichmann was involved in negotiations with Rudolf Kasztner that resulted in the rescue of 1,684 people, who were sent by train to safety in Switzerland in exchange for three suitcases full of diamonds, gold, cash, and securities.

Eichmann, resentful that Kurt Becher and others were becoming involved in Jewish emigration matters, and angered by Himmler's suspension of deportations to the death camps, requested reassignment in July. At the end of August he was assigned to head a commando squad to assist in the evacuation of 10,000 ethnic Germans trapped on the Hungarian border with Romania in the path of the advancing Red Army. The people they were sent to rescue refused to leave, so instead the soldiers helped evacuate members of a German field hospital trapped close to the front. For this Eichmann was awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class. Throughout October and November, Eichmann arranged for tens of thousands of Jewish victims to be forced to march, in appalling conditions, from Budapest to Vienna, a distance of 210 kilometres (130 mi).

On 24 December 1944, Eichmann fled Budapest just before the Soviets completed their encirclement of the capital. He returned to Berlin, where he arranged for the incriminating records of Department IV-B4 to be burned. Along with many other SS officers who fled in the closing months of the war, Eichmann and his family were living in relative safety in Austria when the war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945.

After World War II

At the end of the war, Eichmann was captured by US forces and spent time in several camps for SS officers using forged papers that identified him as Otto Eckmann. He escaped from a work detail at Cham, Germany, when he realised that his identity had been discovered. He obtained new identity papers with the name of Otto Heninger and relocated frequently over the next several months, moving ultimately to the Lüneburg Heath. He initially found work in the forestry industry and later leased a small plot of land in Altensalzkoth, where he lived until 1950. Meanwhile, former commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Höss and others gave damning evidence about Eichmann at the Nuremberg trials of major war criminals starting in 1946.

In 1948, Eichmann obtained a landing permit for Argentina and false identification under the name Ricardo Klement through an organisation directed by Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian cleric and Nazi sympathiser then residing in Italy. These documents enabled him to obtain an International Committee of the Red Cross humanitarian passport and the remaining entry permits in 1950 that would allow emigration to Argentina. He travelled across Europe, staying in a series of monasteries that had been set up as safe houses. He departed from Genoa by ship on 17 June 1950 and arrived in Buenos Aires on 14 July.

Eichmann initially lived in Tucumán Province, where he worked for a government contractor. He sent for his family in 1952, and they moved to Buenos Aires. He held a series of low-paying jobs until finding employment at Mercedes-Benz, where he rose to department head. The family built a house at 14 Garibaldi Street (now 6061 Garibaldi Street) and moved in during 1960.

Eichmann was extensively interviewed for four months beginning in late 1956 by Nazi expatriate journalist Willem Sassen with the intention of producing a biography. Eichmann produced tapes, transcripts, and handwritten notes. The surviving audio recordings became public in 2022. Eichmann confessed that he in fact knew that millions of Jews and others were being killed: "I didn't care about the Jews deported to Auschwitz, whether they lived or died. It was the Fuehrer's order: Jews who were fit to work would work and those who weren't would be sent to the Final Solution." Sassen asked him: "When you say Final Solution, do you mean they should be eradicated?", to which Eichmann replied: "Yes."

The memoirs were used as the basis for a series of articles that appeared in Life and Stern magazines in late 1960. The Sassen tapes form the basis of the documentary series The Devil's Confession: The Lost Eichmann Tapes screened on Israeli television in 2022. The documentary, directed by Yariv Mozer and produced by Kobi Sitt, featured extracts of Eichmann speaking in German.

Capture in Argentina

Several survivors of the Holocaust, among them Jewish Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, dedicated themselves to finding Eichmann and other Nazis. Wiesenthal learned from a letter shown to him in 1953 that Eichmann had been seen in Buenos Aires, and he passed that information to the Israeli consulate in Vienna in 1954. Eichmann's father died in 1960, and Wiesenthal made arrangements for private detectives to surreptitiously photograph members of the family; Eichmann's brother Otto was said to bear a strong family resemblance and there were no current photos of Eichmann. He provided these photographs to Mossad agents on 18 February.

Lothar Hermann, a Jewish German who had emigrated to Argentina in 1938, was also instrumental in exposing Eichmann's identity. His daughter Sylvia began dating a man named Klaus Eichmann in 1956 who boasted about his father's Nazi exploits, and Hermann alerted Fritz Bauer, prosecutor-general of the state of Hesse in West Germany. Hermann then sent his daughter on a fact-finding mission; she was met at the door by Eichmann himself, who said that he was Klaus's uncle. Klaus arrived not long after, however, and addressed Eichmann as "Father". In 1957, Bauer passed the information in person to Mossad director Isser Harel, who assigned operatives to undertake surveillance, but no concrete evidence was initially found. Bauer did not trust the German police or legal system, and feared that if he informed them, they would likely tip off Eichmann. Thus he decided to turn directly to Israeli authorities. Moreover, when Bauer called on the German government to get Eichmann extradited from Argentina, they immediately responded negatively. The government of Israel paid a reward to Hermann in 1971, twelve years after he had provided the information. German geologist Gerhard Klammer, who had worked with Eichmann in the early 1950s, provided Bauer with Eichmann's address and photograph. Klammer's identity was only revealed in 2021.

Harel dispatched Shin Bet chief interrogator Zvi Aharoni to Buenos Aires on 1 March 1960, and he was able to confirm Eichmann's identity after several weeks of investigation. Argentina had a history of turning down extradition requests for Nazi criminals, so rather than filing a probably futile request for extradition, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion made the decision that Eichmann should be captured and brought to Israel for trial. Harel arrived in May 1960 to oversee the capture. Mossad operative Rafi Eitan was named leader of the eight-man team, most of whom were Shin Bet agents.

The team captured Eichmann on 11 May 1960 near his home on Garibaldi Street in San Fernando, Buenos Aires, an industrial community 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of the center of Buenos Aires. The agents had arrived in April and observed his routine for many days, noting that he arrived home from work by bus at about the same time every evening. They planned to seize him when he was walking beside an open field from the bus stop to his house. The plan was almost abandoned on the designated day when Eichmann was not on the bus that he usually took home, but he got off another bus about half an hour later. Mossad agent Peter Malkin engaged him, asking him in Spanish if he had a moment. Eichmann was frightened and attempted to leave, but two more Mossad men came to Malkin's aid. The three wrestled Eichmann to the ground and, after a struggle, moved him to a car where they hid him on the floor under a blanket.

Eichmann was taken to one of several Mossad safe houses that had been set up by the team. He was held there for nine days, during which time his identity was double-checked and confirmed. During these days, Harel tried to locate Josef Mengele, the notorious Nazi doctor from Auschwitz, as Mossad had information that he was also living in Buenos Aires. He was hoping to bring Mengele back to Israel on the same flight. However, Mengele had already left his last known residence in the city, and Harel had no further leads, so the plans for his capture were abandoned. Eitan told the Haaretz newspaper in 2008 that the team decided not to pursue Mengele as it might have jeopardised the Eichmann operation.

Near midnight on 20 May, Eichmann was sedated by an Israeli doctor who was part of the Mossad team and dressed as a flight attendant. He was smuggled out of Argentina aboard the same El Al Bristol Britannia aircraft that had carried Israel's delegation a few days earlier to the official 150th anniversary celebration of the May Revolution. There was a tense delay at the airport while the flight plan was approved, then the plane took off for Israel, stopping in Dakar, Senegal to refuel. They arrived in Israel on 22 May, and Ben-Gurion announced his capture to the Knesset the following afternoon.

In Argentina, news of the abduction was met with a violent wave of antisemitism carried out by far-right elements, including the Tacuara Nationalist Movement. Argentina requested an urgent meeting of the United Nations Security Council in June 1960 after unsuccessful negotiations with Israel, as they regarded the capture to be a violation of their sovereign rights. In the ensuing debate, Israeli representative (and later prime minister) Golda Meir claimed that the abductors were not Israeli agents but private individuals, meaning that the incident was only an "isolated violation of Argentine law." On 23 June, the Council passed Resolution 138, which agreed that Argentine sovereignty had been violated and requested that Israel should make reparations. Israel and Argentina issued a joint statement on 3 August, after further negotiations, admitting the violation of Argentinian sovereignty but agreeing to end the dispute. The Israeli court ruled that the circumstances of Eichmann's capture had no bearing on the legality of his trial.

US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) documents declassified in 2006 show that the capture of Eichmann caused alarm at the CIA and West German Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND). Both organisations had known for at least two years that Eichmann was hiding in Argentina, but they did not act because it did not serve their interests in the Cold War. Both were concerned about what Eichmann might say in his testimony about West German national security advisor Hans Globke, who had coauthored several antisemitic Nazi laws, including the Nuremberg Laws. The documents also revealed that both agencies had used some of Eichmann's former Nazi colleagues to spy on European communist countries.

The assertion that the CIA knew Eichmann's location and withheld that information from the Israelis has been challenged as "ahistorical". Special investigator Eli Rosenbaum cites an unreliable 1958 CIA source which said Eichmann was born in Israel, had lived in Argentina until 1952 under the (erroneous) alias "Clemens", and was living in Jerusalem.

Trial in Jerusalem

Eichmann was taken to a fortified police station at Yagur in Israel, where he spent nine months. The Israelis were unwilling to take him to trial based solely on the evidence in documents and witness testimony, so he was subject to daily interrogations, the transcripts of which totalled over 3,500 pages. The interrogator was Chief Inspector Avner Less of the national police. Using documents provided primarily by Yad Vashem and Nazi hunter Tuviah Friedman, Less was often able to determine when Eichmann was lying or being evasive. When additional information was brought forward that forced Eichmann into admitting what he had done, Eichmann would insist he had no authority in the Nazi hierarchy and was only following orders. Inspector Less noted that Eichmann did not seem to realise the enormity of his crimes and showed no remorse. His pardon plea, released in 2016, did not contradict this: "There is a need to draw a line between the leaders responsible and the people like me forced to serve as mere instruments in the hands of the leaders", Eichmann wrote. "I was not a responsible leader, and as such do not feel myself guilty."

Eichmann's trial before a special tribunal of the Jerusalem District Court began on 11 April 1961. The legal basis of the charges against Eichmann was the 1950 Nazi and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law, under which he was indicted on 15 criminal charges, including crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against the Jewish people, and membership in a criminal organisation. The trial was presided over by three judges: Moshe Landau, Benjamin Halevy and Yitzhak Raveh. The chief prosecutor was Israeli Attorney General Gideon Hausner, assisted by Deputy Attorney General Gabriel Bach and Tel Aviv District Attorney Yaakov Bar-Or. The defence team consisted of German lawyer Robert Servatius, legal assistant Dieter Wechtenbruch, and Eichmann himself. As foreign lawyers had no right of audience before Israeli courts at the time of Eichmann's capture, Israeli law was modified to allow those facing capital charges to be represented by a non-Israeli lawyer. In an Israeli cabinet meeting shortly after Eichmann's capture, Justice Minister Pinchas Rosen stated, "I think that it will be impossible to find an Israeli lawyer, a Jew or an Arab, who will agree to defend him", and thus a foreign lawyer would be necessary.

The Israeli government arranged for the trial to have prominent media coverage. Capital Cities Broadcasting Corporation of the United States obtained exclusive rights to videotape the proceedings for television broadcast. Many major newspapers from all over the globe sent reporters and published front-page coverage of the story. The trial was held at Beit Ha'am (today known as the Gerard Behar Center), an auditorium in central Jerusalem. Eichmann sat inside a bulletproof glass booth to protect him from assassination attempts. The building was modified to allow journalists to watch the trial on closed-circuit television, and 750 seats were available in the auditorium itself. Videotape was flown daily to the United States for broadcast the following day.

The prosecution case was presented over the course of 56 days, involving hundreds of documents and 112 witnesses (many of them Holocaust survivors). Hausner ignored police recommendations to call only 30 witnesses; only 14 of the witnesses called had seen Eichmann during the war. Hausner's intention was to not only demonstrate Eichmann's guilt but to present material about the entire Holocaust, thus producing a comprehensive record. Hausner's opening address began, "It is not an individual that is in the dock at this historic trial and not the Nazi regime alone, but anti-Semitism throughout history." Defense attorney Servatius repeatedly tried to curb the presentation of material not directly related to Eichmann, and was mostly successful. In addition to wartime documents, material presented as evidence included tapes and transcripts from Eichmann's interrogation and Sassen's interviews in Argentina. In the case of the Sassen interviews, only Eichmann's hand-written notes were admitted into evidence.

The defence next engaged in a lengthy direct examination of Eichmann. Observers such as Moshe Pearlman and Hannah Arendt have remarked on Eichmann's ordinariness in appearance and flat affect. In his testimony throughout the trial, Eichmann insisted he had no choice but to follow orders, as he was bound by an oath of loyalty to Hitler – the same superior orders defence used by some defendants in the 1945–1946 Nuremberg trials. Eichmann asserted that the decisions had been made not by him, but by Müller, Heydrich, Himmler, and ultimately Hitler. Servatius also proposed that decisions of the Nazi government were acts of state and therefore not subject to normal judicial proceedings. Regarding the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann stated that he felt a sense of satisfaction and relief at its conclusion. As a clear decision to exterminate had been made by his superiors, the matter was out of his hands; he felt absolved of any guilt. On the last day of the examination, he stated that he was guilty of arranging the transports, but he did not feel guilty for the consequences.

Throughout his cross-examination, prosecutor Hausner attempted to get Eichmann to admit he was personally guilty, but no such confession was forthcoming. Eichmann admitted to not liking the Jews and viewing them as adversaries, but stated that he never thought their annihilation was justified. When Hausner produced evidence that Eichmann had stated in 1945 that "I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction", Eichmann said he meant "enemies of the Reich" such as the Soviets. During later examination by the judges, he admitted he meant the Jews, and said the remark was an accurate reflection of his opinion at the time.

The trial adjourned on 14 August, and the verdict was read on 12 December. Eichmann was convicted on 15 counts of crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against the Jewish people, and membership in a criminal organisation. The judges declared him not guilty of personally killing anyone and not guilty of overseeing and controlling the activities of the Einsatzgruppen. He was deemed responsible for the dreadful conditions on board the deportation trains and for obtaining Jews to fill those trains. In addition to being found guilty of crimes against Jews, he was convicted for crimes against Poles, Slovenes, and Roma. Moreover, Eichmann was found guilty of membership in three organisations that had been declared criminal at the Nuremberg trials: the Gestapo, the SD, and the SS. When considering the sentence, the judges concluded that Eichmann had not merely been following orders, but believed in the Nazi cause wholeheartedly and had been a key perpetrator of the genocide. On 15 December 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging.

Appeals and execution

Eichmann's defence team appealed the verdict to the Israeli Supreme Court. The appeal was heard by a five-judge Supreme Court panel consisting of Supreme Court President Yitzhak Olshan and judges Shimon Agranat, Moshe Zilberg, Yoel Zussman, and Alfred Witkon. The defence team mostly relied on legal arguments about Israel's jurisdiction and the legality of the laws under which Eichmann was charged. Appeal hearings took place between 22 and 29 March 1962. Eichmann's wife Vera flew to Israel and saw him for the last time at the end of April. On 29 May, the Supreme Court rejected the appeal and upheld the District Court's judgment on all counts. Eichmann immediately petitioned Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi for clemency. The content of his letter and other trial documents were made public on 27 January 2016. In addition, Servatius submitted a request for clemency to Ben-Zvi and petitioned for a stay of execution pending his planned appeals for extradition to the West German government. Eichmann's wife and brothers also wrote to Ben-Zvi requesting clemency. Prominent people such as Hugo Bergmann, Pearl S. Buck, Martin Buber, and Ernst Simon spoke against applying the death penalty. Ben-Gurion called a special cabinet meeting to resolve the issue. The cabinet decided to recommend to President Ben-Zvi that Eichmann not be granted clemency, and Ben-Zvi rejected the clemency petition. At 8:00 p.m. on 31 May, Eichmann was informed that the appeal for presidential clemency had been denied.

Eichmann was hanged at a prison in Ramla hours later. The hanging, scheduled for midnight at the end of 31 May, was slightly delayed and thus took place a few minutes past midnight on 1 June 1962. The execution was attended by a small group of officials, four journalists and the Canadian clergyman William Lovell Hull, who had been Eichmann's spiritual counselor while in prison. His last words were reported to be:

Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the three countries with which I have been most connected and which I will not forget. I greet my wife, my family and my friends. I am ready. We'll meet again soon, as is the fate of all men. I die believing in God.

Rafi Eitan, who accompanied Eichmann to the hanging, claimed in 2014 to have heard him later mumble "I hope that all of you will follow me", making those his final words.

Within hours Eichmann's body had been cremated, and his ashes scattered in the Mediterranean Sea, outside Israeli territorial waters, by an Israeli Navy patrol boat.

Eichmann's youngest son Ricardo Eichmann has said he is not resentful toward Israel for executing his father. He does not agree that his father's "following orders" argument excuses his actions and observes how his father's lack of remorse caused "difficult emotions" for the Eichmann family. Ricardo was a professor of archaeology at the German Archaeological Institute until 2020.

Aftermath

The trial received widespread coverage by the press in West Germany, and many schools added material studying the issues to their curricula. In Israel, the testimony of witnesses at the trial led to a deeper awareness of the impact of the Holocaust on survivors, especially among younger citizens. The trial therefore greatly reduced the previously popular misconception that Jews had gone "like sheep to the slaughter".

The use of "Eichmann" as an archetype stems from Hannah Arendt's notion of the "banality of evil". Arendt, a political theorist who reported on Eichmann's trial for The New Yorker, described Eichmann in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem as the embodiment of the "banality of evil", as she thought he appeared to have an ordinary personality, displaying neither guilt nor hatred. In his 1988 book Justice, Not Vengeance, Wiesenthal said: "The world now understands the concept of 'desk murderer'. We know that one doesn't need to be fanatical, sadistic, or mentally ill to murder millions; that it is enough to be a loyal follower eager to do one's duty." The term "little Eichmanns" became a pejorative term for bureaucrats charged with indirectly and systematically harming others.

In her 2011 book Eichmann Before Jerusalem, based largely on the Sassen interviews and Eichmann's notes made while in exile, Bettina Stangneth argues instead that Eichmann was an ideologically motivated antisemite and lifelong committed Nazi who intentionally built a persona as a faceless bureaucrat for presentation at the trial. Historians such as Christopher Browning, Deborah Lipstadt, Yaacov Lozowick, and David Cesarani reached a similar conclusion: that Eichmann was not the unthinking bureaucratic functionary that Arendt believed him to be.