The illegal drug trade in China is influenced by factors such as history, location, size, population, and current economic conditions. China has one-sixth of the world's population and a large and expanding economy. China's large land mass, close proximity to the Golden Triangle, Golden Crescent, and numerous coastal cities with large and modern port facilities make it an attractive transit center for drug traffickers. Opium has played an important role in the country's history since before the First and Second Opium Wars in the mid-19th century.

China's status in drug trafficking has changed significantly since the 1980s, when the country for the first time opened its borders to trade and tourism after 40 years of relative isolation. As trade with Southeast Asia and elsewhere increased, so did the flow of illicit drugs and precursor chemicals from, into, and through China.

Overview

China is a major source of precursor chemicals necessary for the production of fentanyl, cocaine, heroin, MDMA and crystal methamphetamine, which are used by many Southeast Asian and Pacific Rim nations. China produces over 100,000 metric tons of acetic anhydride each year, and imports an additional 20,000 metric tons from the United States and Singapore. Reports indicate that acetic anhydride is diverted from China to morphine and heroin refineries in the Golden Triangle. China is also a leading exporter of bulk ephedrine and has been a source country for much of the ephedrine and pseudoephedrine imported into Mexico; these precursor chemicals are subsequently used to manufacture methamphetamine destined for the United States. China is developing a significant MDMA production, trafficking, and consumption problem. Although China has taken actions through legislation and regulation of production and exportation of precursor chemicals, extensive action is required to control the illicit diversion and smuggling of precursor chemicals.

China not only continues to be a major transit route for Southeast Asian heroin bound for international drug markets, but also for Southwest Asian heroin entering northwestern China from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. A majority of the Southeast Asian heroin that enters China from Myanmar transits southern China to various international markets by maritime transport. Drug traffickers take advantage of expanding port facilities in coastal cities, such as Qingdao, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Guangdong, to ship heroin along maritime routes. Southwest Asian heroin (mainly from Afghanistan) represents as much as 22 percent of the heroin entering northwest China. Chinese authorities believe that these trends will increase and they attribute these increases to the continuing development of the infrastructure and economy in China. China is being forced to develop a complex counter-drug strategy that includes prevention, education, eradication, interdiction, and rehabilitation.

Cultivation and processing

Cannabis

Cannabis grows naturally throughout southwestern China, and is legally cultivated in some areas of China for use in commercial rope manufacturing. Most of the illicit cultivation of cannabis as a drug in China appears in Xinjiang and Yunnan and is primarily cultivated for domestic use. In 2002, approximately 1.3 metric tons of cannabis were seized in China, with over 80 percent of cannabis seized being less than 20 grams.

Ephedra

The Chinese Government owns and operates ephedra farms, where ephedra grass (ephedra sinica) is cultivated under strict government control. The active alkaloids, pseudoephedrine and ephedrine, are chemically extracted from the plant material and processed for pharmaceutical purposes. These chemicals are then sold domestically and for export. China and India are the major producers of these chemicals extracted from the ephedra plant. In addition to government-controlled farms, the ephedra plant grows wildly in many parts of the northern areas of China.

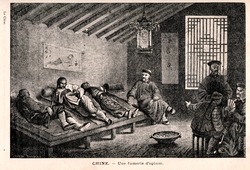

Opium

Illicit cultivation of the opium poppy in China is negligible in provinces such as Yunnan, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and the remote regions of the northwest frontier. Opium produced in these areas is not converted into heroin, but is consumed locally by ethnic minority groups in these isolated areas. Chinese officials report that in the last several years no heroin laboratories have been seized in China.

Legal cultivation of the opium poppy occurs on farms controlled by the Ministry of Agriculture and the National Drug Administration Bureau of the State Council. According to United Nations (UN) International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) data, China produces approximately 14 metric tons (31,000 lb) of legal opium per year for use in the domestic pharmaceutical industry. China reports that none of this opium is exported.

The Mao Zedong government is generally credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s using unrestrained repression and social reform. Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region. The remnant opium trade primarily served Southeast Asia, but spread to American soldiers during the Vietnam War, with 20 per cent of soldiers regarding themselves as addicted during the peak of the epidemic in 1971. In 2003, China was estimated to have four million regular drug users and one million registered drug addicts.

Synthetic drugs

Manufacture of crystal methamphetamine (ice, shabu, bingdu) is facilitated by the availability of precursor chemicals, such as pseudoephedrine and ephedrine. The unrestricted availability of these chemicals in the country facilitates the production of large quantities of crystal methamphetamine. Seizure information indicates that methamphetamine laboratories are located in provinces along the eastern and southeastern coastal areas. Many of the traffickers for the clandestine crystal methamphetamine laboratories are from organized crime groups based in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan.

Because of its increasing popularity with young party goers in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, Chinese law enforcement officials report significant increases in the domestic production of MDMA (Ecstasy). Most MDMA production in China is for domestic consumption. MDMA tablets are also imported from the Netherlands into China to meet the demand.

Some laboratory operators in China mix MDMA powder, imported from Europe, with substances, such as caffeine and ketamine, while making the Ecstasy tablets. Given the availability of the precursor chemicals needed, open source reporting in 2006 indicates that MDMA tablets in China cost only US$0.06 to produce, while the tablets sell for as much as US$36 in Shanghai.

Trafficking

| Year | Arrests | Convictions |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 8,080 | 5,285 |

| 1992 | 7,025 | 6,588 |

| 1993 | 7,677 | 6,137 |

| 1994 | 10,434 | 7,883 |

| 1995 | 12,990 | 9,801 |

| 1996 | 18,860 | 13,787 |

| 1997 | 24,873 | 18,878 |

| 1998 | 34,287 | 27,229 |

| 1999 | 37,627 | 33,641 |

| 2000 | 39,604 | 33,203 |

| 2001 | 40,602 | 33,895 |

| 2002 | 42,854 | 32,222 |

| 2003 | 31,400 | 25,879 |

Trafficking groups

Many of the individuals involved in the international trafficking of Southeast Asian heroin are ethnic Kokang, Yunnanese, Fujianese, Cantonese, or members of other ethnic Chinese minority groups that reside outside of China. These groups reside, and are actively involved in drug trafficking in regions such as Myanmar, Cambodia, Canada, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, and the United States.

Reporting on the activities of drug trafficking organizations in China is sparse. However, Chinese officials report that drug traffickers are dividing their large shipments into smaller ones in order to minimize losses in case of seizure. Chinese officials also report that drug traffickers are increasingly using women, children, and poor, uneducated farmers to body-carry drugs from the Golden Triangle area to Guangdong and other provinces in China.

In China many individuals and criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking are increasingly arming themselves with automatic weapons and grenades to protect their drug shipments from theft by rival organizations. Many firefights occur along the Myanmar–China border, where larger drug shipments are more prevalent. Traffickers also arm themselves to avoid being captured by the police, and some smugglers are better armed than the local police forces. Furthermore, many traffickers believe they have a better chance of surviving a firefight than the outcome of any legal proceedings. In China, sentencing for drug trafficking could include capital punishment. For example, the seizure of 50 grams or more of heroin or crystal methamphetamine could result in the use of the death penalty by the Government.

Hui Muslim drug dealers are accused by Uyghur Muslims of pushing heroin on Uyghurs. Heroin has been vended by Hui dealers. There is a typecast image in the public eye of heroin being the province of Hui dealers. Hui have been involved in the Golden Triangle drug area.

Drug seizures

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin | 2,376 | 4,347 | 5,478 | 7,358 | 5,364 | 6,281 | 13.2 | 9.29 | 4.07 |

| Opium | 1.11 | 1,745 | 1,880 | 1,215 | 1,193 | 2,428 | 2.82 | 1.2 | N/A |

| Precursor chemicals | 86 | 219 | 383 | 344 | 272 | 215 | 208 | 300 | N/A |

| Marijuana | 0,466 | 4,876 | 2,408 | 5,079 | 0,106 | 4,493 | 0,751 | 1.3 | N/A |

| Crystal methamphetamine | 1,304 | 1,599 | 1,334 | 1,608 | 16,059 | 20.9 | 4.82 | 3.19 | 4.53 |

Heroin

China shares a 2000 km border with Myanmar, as well as smaller but significant borders with Laos and Vietnam. Chinese officials state that the majority of heroin entering China comes over the border from Myanmar. This heroin then transits southern China, through Yunnan or Guangxi, to Guangdong or Fujian to the southeastern coastal areas, and then on to international markets. Heroin is transported by various overland methods to ports in China's southeastern provinces of Guangdong and Fujian.

Heroin is transported to Guangdong and to the cities of Xiamen and Fuzhou in Fujian for shipment to international drug markets. Traffickers take advantage of expanding port facilities in northeast cities, such as Qingdao, Shanghai, and Tianjin, to ship heroin via maritime routes. Increased Chinese interdiction efforts along the Myanmar–China border have forced some traffickers to send heroin from Myanmar to China's southeastern provinces by fishing trawlers.

In addition to Southeast Asian heroin entering into China, Southwest Asian heroin enters northwestern China from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. Chinese authorities state that Southwest Asian heroin (mainly originating from Afghanistan) represents as much as 20 percent of the heroin that enters the northwest Xinjiang. This trend is increasing, and is attributed to the continuing development of the infrastructure and economy in the western parts of China.

Synthetic drugs

Due to the availability of the precursor chemicals, traffickers produce large amounts of crystal methamphetamine. Although much of the crystal methamphetamine is consumed locally, some is available for shipment to other markets throughout Southeast Asia. Several ports in southern China serve as transit points for crystal methamphetamine transported by containerized cargo to international drug markets.

Some MDMA traffickers in China are linked directly to the United States. In June 2001, tablets from seizures in two DEA San Francisco investigations were linked to the same source as a 300,000-tablet seizure in Shenzhen, China that had occurred days before. Although the San Francisco seizures were much smaller than the Shenzhen seizure, the capabilities of these trafficking groups appear to be significant. Chinese officials seized over 3 million Ecstasy tablets in China in 2002.

Another case involved Liu Zhaohua, who produced up to 31 tonnes of methamphetamine and made more than $5.5 billion USD from it. In 2006, during the term of Hu Jintao, Liu was sentenced to death for drug trafficking, and in 2009 Liu was executed.

Precursor chemicals

China is of paramount importance in global cooperative efforts to prevent the diversion of precursor chemicals. With its large chemical industry, China remains a source country for legitimately produced chemicals that are diverted for production of heroin and cocaine, as well as many amphetamine-type stimulants. China and its neighbor India are the leading exporters of bulk ephedrine in the world. China produces over 100,000 metric tons of acetic anhydride each year, and imports an additional 20,000 metric tons from the United States and Singapore. China is also the second largest producer of potassium permanganate in the world.

To combat the diversion of precursor chemicals, China implemented several regulations on the control of precursor chemicals between 1992 and 1998, including adoption of the 1988 U.N. Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances in 1993. Additionally, the Government further improved regulations to strengthen control of ephedrine during 1999 and 2000.

China fully participates in the DEA's Operations TOPAZ and PURPLE, which are international monitoring initiatives that target acetic anhydride and potassium permanganate, respectively. Acetic anhydride is used to synthesize morphine base into heroin, and potassium permanganate is used as an oxidizer in cocaine production. Both chemicals are targeted because they are the chemicals most often preferred, and most widely used, by illicit drug manufacturers. However, the effectiveness of Operation PURPLE has been declining recently, since participant nations are exporting significant amounts of potassium permanganate to non-participant countries.

Additionally, Chinese authorities further control the export of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine through the voluntary use of the Letter of Non-Objection (LONO) system. China will not allow exports of ephedrine or pseudoephedrine without a positive affirmation by authorities in the importing country as to the bona fides of the consignee. For those countries that do not issue import permits, a letter of non-objection must be provided to Chinese authorities.

China is a source country for significant amounts of the ephedrine and pseudoephedrine exported to Mexico, and subsequently used to manufacture methamphetamine destined for the United States.

Increases in pseudoephedrine diversion were noted, beginning with the seizures in March and April 2003 of four shipments of product destined for Mexico. The seizures occurred in the United States and Panama, and totaled over 22 million, 60-milligram pseudoephedrine tablets. The source of supply has been identified as legitimate pharmaceutical companies in Hong Kong. Additional investigations have revealed other companies in Hong Kong that have been engaged in supplying substantial amounts of pseudoephedrine to firms, sometime fictitious, shells or fronts, in Mexico.

Also, reports indicate that acetic anhydride is diverted from China to morphine/heroin refineries found in the Golden Triangle. Domestically, Chinese officials express concern over the increasing number of synthetic drug production operations in their country. Seizures of precursor chemicals in China increased from 50 metric tons in 1991 to 383 metric tons in 1997; only 300 metric tons were seized in 2002.

In the past money laundering was not considered a significant problem in China. However, with the booming economy promoting greater trade investment and the ever-increasing number of foreign bank branches opening throughout the country, it appears that China may become an emerging money laundering center.

China, however, has taken some initial steps to begin investigation of money laundering activities. An Economic Crimes Investigation Department was established in the Ministry of Public Security to focus on illicit activities. The People's Bank of China (China's central bank) began several structural reforms such as the establishment of two new divisions, the Payment Trade Supervisory Division and the Money Laundering Working Division. The People's Bank of China also prepared guidelines for use by financial institutions to report suspicious transactions, and to sensitize the public about new regulations on money laundering and terrorist financing issues.

Drug abuse and treatment

Drugs of choice

| Drug | Location | Price |

|---|---|---|

| Southeast Asian heroin (price per 1 unit = 700 grams) | Guangzhou | $18,000 |

| Fuzhou | 18,000 | |

| Burmese border | 5,000 | |

| Crystal methamphetamine (price per kilogram) | Guangzhou | 3,700 |

| Xiamen | 4,000 | |

| MDMA (price per tablet) | Beijing | 27-36 |

| Shanghai | 27-36 | |

| Guangzhou | 9 | |

| Fuzhou | 9 |

The major drugs of choice are injectable heroin, morphine, smokeable opium, crystal methamphetamine, nimetazepam, temazepam, and MDMA. Preferences between opium and heroin/morphine, and methods of administration, differ from region to region within China. The use of heroin and opium has increased among the younger population, as income has grown and the youth have more free time. China considers crystal methamphetamine abuse second to heroin/morphine as a major drug problem. The use of MDMA has only recently become popular in China's growing urban areas.

The South China Morning Post reports the rise in the use of ketamine, easy to mass-produce in illicit labs in southern China, particularly among the young. Because of its low cost, and low profit margin, drug peddlers rely on mass distribution to make money, thus increasing its penetrative power to all, including schoolchildren. The journal cites social workers saying that four people can get high by sharing just HK$20 worth of ketamine, and estimates 80 per cent of young drug addicts take 'K'.

Addict population

As of 2013, there were 2,475,000 registered drug addicts in China, 1,326,000 of which were addicted to heroin, accounting for 53.6% of the addict population. Some unofficial estimates range as high as 12 million drug addicts. Of the registered drug addicts, 83.7 percent are male and 73.9 percent are under the age of 35.

In 2001, intravenous heroin users accounted for 70.9 percent of the confirmed 22,000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) cases. Chinese officials are becoming increasingly concerned about the abuse of methamphetamine and other amphetamine-type stimulants.

Treatment and demand reduction programs

Both voluntary and compulsory drug treatment programs are provided in China, although the compulsory treatment is more common. Most addicts who attend these centers do so involuntarily upon orders from the Government. Voluntary treatment is provided at centers operated by Public Health Bureaus, but these programs are more expensive and many people cannot afford to attend them. Addicts who return to drug use after having received treatment, and cannot be cured by other means, may be sentenced to rehabilitation in labor camps for re-education through labor. These centers are run under conditions similar to prisons, including isolation from the outside world, restricted patient movement and a paramilitary routine.

Demand reduction efforts target individuals between the ages of 17 and 35, since this is the largest segment of drug users. These efforts include, but are not limited to, media campaigns and establishment of drug-free communities.

Drug law enforcement agencies and legislation

At the national level, the agencies specifically responsible for the control of legal and illicit drugs are the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Customs General Administration. The State Food and Drug Administration oversees implementation of the laws regulating the pharmaceutical industry. In the Customs General Administration, the Smuggling Prevention Department plays the major role in intercepting illegal drug shipments. The Narcotics Control Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security handles all criminal investigations involving opium, heroin, and methamphetamine.

In 1990, the Chinese government set up the National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), composed of 25 departments, including the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Health and General Administration of Customs. The NNCC leads the nation's drug control work in a unified way, and is responsible for international drug control cooperation, with an operational agency based in the Ministry of Public Security.

Treaties and conventions

China is a party to the 1988 U.N. Drug Convention, the 1961 U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 Protocol, and the 1971 U.N. Convention on Psychotropic Substances. China is a member of the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), and has been a member of the INCB since 1984.

China also participates in a drug control program with Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Russia, and the United States. This program is designed to enhance information sharing and coordination of drug law enforcement activities by countries in and around the Central Asian Region.

In June 2000, China and the United States signed a Mutual Legal Assistance Agreement (MLAT). This treaty subsequently went into effect on March 8, 2001. In 1999, China and the United States signed a Bilateral Customs Mutual Assistance Agreement. However, this agreement has not yet been activated. A May 1997 United States and China Memorandum of Understanding on law enforcement cooperation allows the two countries to provide assistance on drug investigations and prosecutions on a case-by-case basis.

China has over 30 MLATs with 24 nations covering both civil and criminal matters. In 1996, China signed MLATs that gave specific attention to drug trafficking with Russia, Mexico, and Pakistan. China also signed a drug control cooperation agreement with India.

China and Myanmar continue dialogue on counter-drug issues, such as drug trafficking by the United Wa State Army along the China–Myanmar border. The Government of China encourages and provides assistance for alternative crop programs in Myanmar along the China–Myanmar border. China is also building on Memoranda of Understanding that are currently in place with Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.