Rainforest ecosystems are rich in biodiversity. This is the Gambia River in Senegal's Niokolo-Koba National Park.

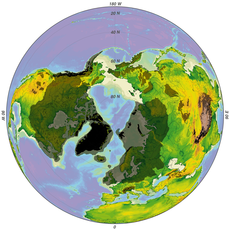

This article is about climate change and ecosystems. Future climate change is expected to affect particular ecosystems, including tundra, mangroves, coral reefs, and caves.

General

Unchecked global warming could affect most terrestrial ecoregions. Increasing global temperature means that ecosystems will change; some species are being forced out of their habitats (possibly to extinction)

because of changing conditions, while others are flourishing. Secondary

effects of global warming, such as lessened snow cover, rising sea

levels, and weather changes, may influence not only human activities but

also the ecosystem.

For the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, experts assessed the literature on the impacts of climate change on ecosystems. Rosenzweig et al.

(2007) concluded that over the last three decades, human-induced

warming had likely had a discernible influence on many physical and

biological systems (p. 81). Schneider et al. (2007) concluded, with very high confidence, that regional temperature trends had already affected species and ecosystems around the world (p. 792).

With high confidence, they concluded that climate change would result

in the extinction of many species and a reduction in the diversity of

ecosystems (p. 792).

- Terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity: With a warming of 3 °C, relative to 1990 levels, it is likely that global terrestrial vegetation would become a net source of carbon (Schneider et al., 2007:792). With high confidence, Schneider et al. (2007:788) concluded that a global mean temperature increase of around 4 °C (above the 1990-2000 level) by 2100 would lead to major extinctions around the globe.

- Marine ecosystems and biodiversity: With very high confidence, Schneider et al. (2007:792) concluded that a warming of 2 °C above 1990 levels would result in mass mortality of coral reefs globally. In addition, several studies dealing with planktonic organisms and modelling have shown that temperature plays a transcendental role in marine microbial food webs, which may have a deep influence on the biological carbon pump of marine planktonic pelagic and mesopelagic ecosystems.

- Freshwater ecosystems: Above about a 4 °C increase in global mean temperature by 2100 (relative to 1990-2000), Schneider et al. (2007:789) concluded, with high confidence, that many freshwater species would become extinct.

Impacts

Studying the association between Earth climate and extinctions over the past 520 million years, scientists from the University of York

write, "The global temperatures predicted for the coming centuries may

trigger a new ‘mass extinction event’, where over 50 per cent of animal

and plant species would be wiped out."

Many of the species at risk are Arctic and Antarctic fauna such as polar bears and emperor penguins. In the Arctic, the waters of Hudson Bay are ice-free for three weeks longer than they were thirty years ago, affecting polar bears, which prefer to hunt on sea ice. Species that rely on cold weather conditions such as gyrfalcons, and snowy owls that prey on lemmings that use the cold winter to their advantage may be hit hard. Marine invertebrates enjoy peak growth at the temperatures they have adapted to, regardless of how cold these may be, and cold-blooded animals found at greater latitudes and altitudes generally grow faster to compensate for the short growing season. Warmer-than-ideal conditions result in higher metabolism and consequent reductions in body size despite increased foraging, which in turn elevates the risk of predation. Indeed, even a slight increase in temperature during development impairs growth efficiency and survival rate in rainbow trout.

Rising temperatures are beginning to have a noticeable impact on birds, and butterflies

have shifted their ranges northward by 200 km in Europe and North

America. Plants lag behind, and larger animals' migration is slowed down

by cities and roads. In Britain, spring butterflies are appearing an

average of 6 days earlier than two decades ago.

A 2002 article in Nature

surveyed the scientific literature to find recent changes in range or

seasonal behaviour by plant and animal species. Of species showing

recent change, 4 out of 5 shifted their ranges towards the poles or

higher altitudes, creating "refugee species". Frogs were breeding,

flowers blossoming and birds migrating an average 2.3 days earlier each

decade; butterflies, birds and plants moving towards the poles by 6.1 km

per decade. A 2005 study concludes human activity is the cause of the

temperature rise and resultant changing species behaviour, and links

these effects with the predictions of climate models to provide validation for them. Scientists have observed that Antarctic hair grass is colonizing areas of Antarctica where previously their survival range was limited.

Mechanistic studies have documented extinctions due to recent climate change: McLaughlin et al. documented two populations of Bay checkerspot butterfly being threatened by precipitation change.

Parmesan states, "Few studies have been conducted at a scale that encompasses an entire species" and McLaughlin et al. agreed "few mechanistic studies have linked extinctions to recent climate change." Daniel Botkin and other authors in one study believe that projected rates of extinction are overestimated. For "recent" extinctions, see Holocene extinction.

Many species of freshwater and saltwater plants and animals are

dependent on glacier-fed waters to ensure a cold water habitat that they

have adapted to. Some species of freshwater fish need cold water to

survive and to reproduce, and this is especially true with salmon and cutthroat trout. Reduced glacier runoff can lead to insufficient stream flow to allow these species to thrive. Ocean krill, a cornerstone species, prefer cold water and are the primary food source for aquatic mammals such as the blue whale. Alterations to the ocean currents, due to increased freshwater inputs from glacier melt, and the potential alterations to thermohaline circulation of the worlds oceans, may affect existing fisheries upon which humans depend as well.

The white lemuroid possum, only found in the Daintree

mountain forests of northern Queensland, may be the first mammal species

to be driven extinct by global warming in Australia. In 2008, the white

possum has not been seen in over three years. The possums cannot

survive extended temperatures over 30 °C (86 °F), which occurred in

2005.

A 27-year study of the largest colony of Magellanic penguins

in the world, published in 2014, found that extreme weather caused by

climate change is responsible for killing 7% of penguin chicks per year

on average, and in some years studied climate change accounted for up to

50% of all chick deaths. Since 1987, the number of breeding pairs in the colony has reduced by 24%.

Climate change is leading to a mismatch between the snow camouflage of arctic animals such as snowshoe hares with the increasingly snow-free landscape.

Forests

Change in Photosynthetic Activity in Northern Forests 1982-2003; NASA Earth Observatory

Pine forests in British Columbia have been devastated by a pine beetle

infestation, which has expanded unhindered since 1998 at least in part

due to the lack of severe winters since that time; a few days of extreme

cold kill most mountain pine beetles and have kept outbreaks in the

past naturally contained. The infestation, which (by November 2008) has

killed about half of the province's lodgepole pines (33 million acres or

135,000 km²) is an order of magnitude larger than any previously recorded outbreak.

One reason for unprecedented host tree mortality may be due to that the

mountain pine beetles have higher reproductive success in lodgepole

pine trees growing in areas where the trees have not experienced

frequent beetle epidemics, which includes much of the current outbreak

area. In 2007 the outbreak spread, via unusually strong winds, over the continental divide to Alberta. An epidemic also started, be it at a lower rate, in 1999 in Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana. The United States forest service predicts that between 2011 and 2013 virtually all 5 million acres (20,000 km2) of Colorado’s lodgepole pine trees over five inches (127 mm) in diameter will be lost.

As the northern forests are a carbon sink,

while dead forests are a major carbon source, the loss of such large

areas of forest has a positive feedback on global warming. In the worst

years, the carbon emission due to beetle infestation of forests in

British Columbia alone approaches that of an average year of forest

fires in all of Canada or five years worth of emissions from that country's transportation sources.

Besides the immediate ecological and economic impact, the huge

dead forests provide a fire risk. Even many healthy forests appear to

face an increased risk of forest fires

because of warming climates. The 10-year average of boreal forest

burned in North America, after several decades of around 10,000 km² (2.5

million acres), has increased steadily since 1970 to more than

28,000 km² (7 million acres) annually.

Though this change may be due in part to changes in forest management

practices, in the western U.S., since 1986, longer, warmer summers have

resulted in a fourfold increase of major wildfires and a sixfold

increase in the area of forest burned, compared to the period from 1970

to 1986. A similar increase in wildfire activity has been reported in

Canada from 1920 to 1999.

Forest fires in Indonesia

have dramatically increased since 1997 as well. These fires are often

actively started to clear forest for agriculture. They can set fire to

the large peat bogs in the region and the CO₂released by these peat bog

fires has been estimated, in an average year, to be 15% of the quantity

of CO₂produced by fossil fuel combustion.

A 2018 study found that trees grow faster due to increased carbon

dioxide levels, however, the trees are also eight to twelve percent

lighter and denser since 1900. The authors note, "Even though a greater

volume of wood is being produced today, it now contains less material

than just a few decades ago."

Mountains

Mountains

cover approximately 25 percent of earth's surface and provide a home to

more than one-tenth of global human population. Changes in global

climate pose a number of potential risks to mountain habitats. Researchers expect that over time, climate change will affect mountain and lowland ecosystems, the frequency and intensity of forest fires, the diversity of wildlife, and the distribution of fresh water.

Studies suggest a warmer climate in the United States would

cause lower-elevation habitats to expand into the higher alpine zone.

Such a shift would encroach on the rare alpine meadows and other

high-altitude habitats. High-elevation plants and animals have limited

space available for new habitat as they move higher on the mountains in

order to adapt to long-term changes in regional climate.

Changes in climate will also affect the depth of the mountains

snowpacks and glaciers. Any changes in their seasonal melting can have

powerful impacts on areas that rely on freshwater runoff

from mountains. Rising temperature may cause snow to melt earlier and

faster in the spring and shift the timing and distribution of runoff.

These changes could affect the availability of freshwater for natural

systems and human uses.

Oceans

Ocean Acidification

Estimated

annual mean sea surface anthropogenic dissolved inorganic carbon

concentration for the present day (normalised to year 2002) from the

Global Ocean Data Analysis Project v2 (GLODAPv2) climatology.

Annual mean sea surface dissolved oxygen from the World Ocean Atlas 2009. Dissolved oxygen here is in mol O2m-3.

Ocean acidification poses a severe threat to the earth's natural process of regulating atmospheric C02 levels, causing a decrease in water's ability to dissolve oxygen and created oxygen-vacant bodies of water called "dead zones." The ocean absorbs up to 55% of atmospheric carbon dioxide, lessoning the effects of climate change. This diffusion of carbon dioxide into seawater results in three acidic molecules: bicarbonate ion (HCO3-), aqueous carbon dioxide (CO2aq), and carbonic acid (H2CO3).

These three compounds increase the ocean's acidity, decreasing its ph

by up to 0.1 per 100ppm (part per million) of atmospheric CO2.

The increase of ocean acidity also decelerates the rate of

calcification in salt water, leading to slower growing reefs which

support a whopping 25% of marine life.

As seen with the great barrier reef, the increase in ocean acidity in

not only killing the coral, but also the wildly diverse population of

marine inhabitants which coral reefs support.

Dissolved Oxygen

Another

issue faced by increasing global temperatures is the decrease of the

ocean's ability to dissolve oxygen, one with potentially more severe

consequences than other repercussions of global warming.

Ocean depths between 100 meters and 1,000 meters are known as "oceanic

mid zones" and host a plethora of biologically diverse species, one of

which being zooplankton. Zooplankton feed on smaller organisms such as phytoplankton, which are an integral part of the marine food web.

Phytoplankton perform photosynthesis, receiving energy from light, and

provide sustenance and energy for the larger zooplankton, which provide

sustenance and energy for the even larger fish, and so on up the food

chain.

The increase in oceanic temperatures lowers the ocean's ability to

retain oxygen generated from phytoplankton, and therefore reduces the

amount of bioavailable oxygen that fish and other various marine

wildlife rely on for their survival.

This creates marine dead zones, and the phenomenon has already

generated multiple marine dead zones around the world, as marine

currents effectively "trap" the deoxygenated water.

Combined Impact

Eventually

the planet will warm to such a degree that the ocean's ability to

dissolve water will no longer exist, resulting in a worldwide dead zone.

Dead zones, in combination with ocean acidification, will usher in an

era where marine life in most forms will cease to exist, causing a sharp

decline in the amount of oxygen generated through bio carbon

sequestration, perpetuating the cycle.

This disruption to the food chain will cascade upward, thinning out

populations of primary consumers, secondary consumers, tertiary

consumers, etc., as primary consumers being the initial victims of these

phenomenon.

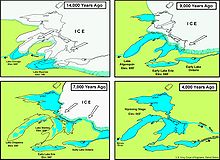

Fresh Water

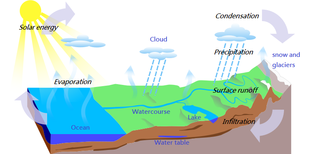

Disruption to Water-Cycle

The Water Cycle

Fresh water covers only 0.8% of the Earth's surface, but contains up to 6% of all life on the planet.

However, the impacts climate change deal to its ecosystems are often

overlooked. Very few studies showcase the potential results of climate

change on large-scale ecosystems which are reliant on freshwater, such

as river ecosystems, lake ecosystems, desert ecosystems, etc. However, a

comprehensive study published in 2009 delves into the effects to be

felt by lotic (flowing) and lentic (still) freshwater ecosystems in the

American Northeast. According to the study, persistent rainfall,

typically felt year round, will begin to diminish and rates of

evaporation will increase, resulting in drier summers and more sporadic

periods of precipitation throughout the year.

Additionally, a decrease in snowfall is expected, which leads to less

runoff in the spring when snow thaws and enters the watershed, resulting

in lower-flowing fresh water rivers.

This decrease in snowfall also leads to increased runoff during winter

months, as rainfall cannot permeate the frozen ground usually covered by

water-absorbing snow. These effects on the water cycle will wreak havoc for indigenous species residing in fresh water lakes and streams.

Salt Water Contamination and Cool Water Species

Eagle River in central Alaska, home to various indigenous freshwater species.

Species of fish living in cold or cool water can see a reduction in

population of up to 50% in the majority of U.S. fresh water streams,

according to most climate change models.

The increase in metabolic demands due to higher water temperatures, in

combination with decreasing amounts of food will be the main

contributors to their decline.

Additionally, many fish species (such as salmon) utilize seasonal water

levels of streams as a means of reproducing, typically breeding when

water flow is high and migrating to the ocean after spawning.

Because snowfall is expected to be reduced due to climate change, water

runoff is expected to decrease which leads to lower flowing streams,

effecting the spawning of millions of salmon.

To add to this, rising seas will begin to flood coastal river systems,

converting them from fresh water habitats to saline environments where

indigenous species will likely perish. In southeast Alaska, the sea

rises by 3.96cm/year, redepositing sediment in various river channels

and bringing salt water inland.

This rise in sea level not only contaminates streams and rivers with

saline water, but also the reservoirs they are connected to, where

species such as Sockeye Salmon live. Although this species of Salmon can

survive in both salt and fresh water, the loss of a body of fresh water

stops them from reproducing in the spring, as the spawning process

requires fresh water.

Undoubtedly, the loss of fresh water systems of lakes and rivers in

Alaska will result in the imminent demise of the state's once-abundant

population of salmon.

Combined Impact

In

general, as the planet warms, the amount of fresh water bodies across

the planet decreases, as evaporation rates increase, rain patterns

become more sporadic , and watershed patterns become fragmented,

resulting in less cyclical water flow in river and stream systems. This

disruption to fresh water cycles disrupts the feeding, mating, and

migration patterns of organisms reliant on fresh water ecosystems.

Additionally, the encroachment of saline water into fresh water river

systems endangers indigenous species which can only survive in fresh

water.

Ecological productivity

- According to a paper by Smith and Hitz (2003:66), it is reasonable to assume that the relationship between increased global mean temperature and ecosystem productivity is parabolic. Higher carbon dioxide concentrations will favourably affect plant growth and demand for water. Higher temperatures could initially be favourable for plant growth. Eventually, increased growth would peak then decline.

- According to IPCC (2007:11), a global average temperature increase exceeding 1.5–2.5 °C (relative to the period 1980–99), would likely have a predominantly negative impact on ecosystem goods and services, e.g., water and food supply.

- Research done by the Swiss Canopy Crane Project suggests that slow-growing trees only are stimulated in growth for a short period under higher CO2 levels, while faster growing plants like liana benefit in the long term. In general, but especially in rainforests, this means that liana become the prevalent species; and because they decompose much faster than trees their carbon content is more quickly returned to the atmosphere. Slow growing trees incorporate atmospheric carbon for decades.

Species migration

In 2010, a gray whale

was found in the Mediterranean Sea, even though the species had not

been seen in the North Atlantic Ocean since the 18th century. The whale

is thought to have migrated from the Pacific Ocean via the Arctic.

Climate Change & European Marine Ecosystem Research (CLAMER) has also reported that the Neodenticula seminae

alga has been found in the North Atlantic, where it had gone extinct

nearly 800,000 years ago. The alga has drifted from the Pacific Ocean

through the Arctic, following the reduction in polar ice.

In the Siberian subarctic,

species migration is contributing to another warming albedo-feedback,

as needle-shedding larch trees are being replaced with dark-foliage

evergreen conifers which can absorb some of the solar radiation that

previously reflected off the snowpack beneath the forest canopy.

It has been projected many fish species will migrate towards the North

and South poles as a result of climate change, and that many species of

fish near the Equator will go extinct as a result of global warming.

Migratory birds are especially at risk for endangerment due to

the extreme dependability on temperature and air pressure for migration,

foraging, growth, and reproduction. Much research has been done on the

effects of climate change on birds, both for future predictions and for

conservation. The species said to be most at risk for endangerment or

extinction are populations that are not of conservation concern.

It is predicted that a 3.5 degree increase in surface temperature will

occur by year 2100, which could result in between 600 and 900

extinctions, which mainly will occur in the tropical environments.

Agriculture

Droughts have been occurring more frequently because of global

warming and they are expected to become more frequent and intense in

Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, most of the Americas,

Australia, and Southeast Asia.

Their impacts are aggravated because of increased water demand,

population growth, urban expansion, and environmental protection efforts

in many areas. Droughts result in crop failures and the loss of pasture grazing land for livestock.

Droughts are becoming more frequent and intense in arid and semiarid

western North America as temperatures have been rising, advancing the

timing and magnitude of spring snow melt floods and reducing river flow

volume in summer. Direct effects of climate change include increased

heat and water stress, altered crop phenology,

and disrupted symbiotic interactions. These effects may be exacerbated

by climate changes in river flow, and the combined effects are likely to

reduce the abundance of native trees in favor of non-native herbaceous

and drought-tolerant competitors, reduce the habitat quality for many

native animals, and slow litter decomposition and nutrient cycling.

Climate change effects on human water demand and irrigation may

intensify these effects.

By 2012, North American corn prices had risen to a record $8.34 per

bushel in August, leaving 20 of the 211 U.S. ethanol fuel plants idle.