From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

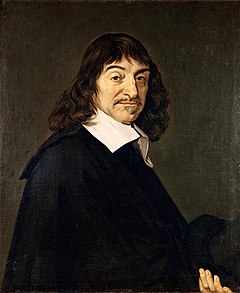

| René Descartes | |

|---|---|

Portrait after Frans Hals, 1648[1]

|

|

| Born | 31 March 1596 La Haye en Touraine, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 11 February 1650 (aged 53) Stockholm, Swedish Empire |

| Nationality | French |

| Religion | Catholic[2] |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Cartesianism, rationalism, foundationalism, founder of Cartesianism |

Main interests

|

metaphysics, epistemology, mathematics |

Notable ideas

|

Cogito ergo sum, method of doubt, method of normals, Cartesian coordinate system, Cartesian dualism, ontological argument for the existence of God, mathesis universalis; folium of Descartes |

| Signature | |

René Descartes (/ˈdeɪˌkɑrt/;[5] French: [ʁəne dekaʁt]; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; adjectival form: "Cartesian";[6] 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician and writer who spent most of his life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the father of modern philosophy, and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings,[7][8] which are studied closely to this day. In particular, his Meditations on First Philosophy continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes' influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the Cartesian coordinate system — allowing reference to a point in space as a set of numbers, and allowing algebraic equations to be expressed as geometric shapes in a two-dimensional coordinate system (and conversely, shapes to be described as equations) — was named after him. He is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. Descartes was also one of the key figures in the scientific revolution and has been described as an example of genius. He refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers, and refused to trust his own senses. Descartes frequently sets his views apart from those of his predecessors. In the opening section of the Passions of the Soul, a treatise on the early modern version of what are now commonly called emotions, Descartes goes so far as to assert that he will write on this topic "as if no one had written on these matters before".

Many elements of his philosophy have precedents in late Aristotelianism, the revived Stoicism of the 16th century, or in earlier philosophers like Augustine. In his natural philosophy, he differs from the schools on two major points: First, he rejects the splitting of corporeal substance into matter and form; second, he rejects any appeal to final ends—divine or natural—in explaining natural phenomena.[9] In his theology, he insists on the absolute freedom of God's act of creation.

Descartes laid the foundation for 17th-century continental rationalism, later advocated by Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, and opposed by the empiricist school of thought consisting of Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Leibniz, Spinoza and Descartes were all well versed in mathematics as well as philosophy, and Descartes and Leibniz contributed greatly to science as well.

His best known philosophical statement is "Cogito ergo sum" (French: Je pense, donc je suis; I think, therefore I am), found in part IV of Discourse on the Method (1637 – written in French but with inclusion of "Cogito ergo sum") and §7 of part I of Principles of Philosophy (1644 – written in Latin).

Early life

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine (now Descartes), Indre-et-Loire, France. When he was one year old, his mother Jeanne Brochard died. His father Joachim was a member of the Parlement of Brittany at Rennes.[10] René lived with his grandmother and with his great-uncle. Although the Descartes family was Roman Catholic, the Poitou region was controlled by the Protestant Huguenots.[11] In 1607, late because of his fragile health, he entered the Jesuit Collège Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche[12] where he was introduced to mathematics and physics, including Galileo's work.[13] After graduation in 1614, he studied two years at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and Licence in law, in accordance with his father's wishes that he should become a lawyer.[14] From there he moved to Paris.

In his book, Discourse On The Method, he says "I entirely abandoned the study of letters. Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that of which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth traveling, visiting courts and armies, mixing with people of diverse temperaments and ranks, gathering various experiences, testing myself in the situations which fortune offered me, and at all times reflecting upon whatever came my way so as to derive some profit from it."

Given his ambition to become a professional military officer, in 1618, Descartes joined the Dutch States Army in Breda under the command of Maurice of Nassau, and undertook a formal study of military engineering, as established by Simon Stevin. Descartes therefore received much encouragement in Breda to advance his knowledge of mathematics.[15] In this way he became acquainted with Isaac Beeckman, principal of a Dordrecht school, for whom he wrote the Compendium of Music (written 1618, published 1650). Together they worked on free fall, catenary, conic section and Fluid statics. Both believed that it was necessary to create a method that thoroughly linked mathematics and physics.[16] While in the service of the Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, Descartes visited the labs of Tycho Brahe in Prague and Johannes Kepler in Regensburg.

Visions

According to Adrien Baillet, on the night of 10–11 November 1619 (St. Martin's Day), while stationed in Neuburg an der Donau, Descartes shut himself in a room with an "oven" (probably a Kachelofen or masonry heater) to escape the cold. While within, he had three visions and believed that a divine spirit revealed to him a new philosophy.[17] Upon exiting he had formulated analytical geometry and the idea of applying the mathematical method to philosophy. He concluded from these visions that the pursuit of science would prove to be, for him, the pursuit of true wisdom and a central part of his life's work.[18][19] Descartes also saw very clearly that all truths were linked with one another, so that finding a fundamental truth and proceeding with logic would open the way to all science. This basic truth, Descartes found quite soon: his famous "I think therefore I am".[16]In 1620 he left the army. Descartes visited Basilica della Santa Casa in Loreto and other countries. He returned to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris. It was there that he composed his first essay on method: Regulae ad Directionem Ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind).[16] He arrived in La Haye in 1623, selling all of his property to invest in bonds, which provided a comfortable income for the rest of his life. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627. In the fall of the same year, in the residence of the papal nuncio Guidi di Bagno, where he came with Mersenne and many other scholars to listen to a lecture given by the alchemist Monsieur de Chandoux on the principles of a supposed new philosophy,[20] Cardinal Bérulle urged him to write an exposition of his own new philosophy.

Work

He returned to the Dutch Republic in 1628. In April 1629 he joined the University of Franeker, studying under Metius, living either with a Catholic family, or renting the Sjaerdemaslot, where he invited in vain a French cook and an optician. The next year, under the name "Poitevin", he enrolled at the Leiden University to study mathematics with Jacob Golius, who confronted him with Pappus's hexagon theorem, and astronomy with Martin Hortensius.[21] In October 1630 he had a falling-out with Beeckman, whom he accused of plagiarizing some of his ideas. In Amsterdam, he had a relationship with a servant girl, Helena Jans van der Strom, with whom he had a daughter, Francine, who was born in 1635 in Deventer, at which time Descartes taught at the Utrecht University. Unlike many moralists of the time, Descartes was not devoid of passions but rather defended them; he wept upon her death in 1640.[22] "Descartes said that he did not believe that one must refrain from tears to prove oneself a man." Russell Shorto postulated that the experience of fatherhood and losing a child formed a turning point in Descartes' work, changing its focus from medicine to a quest for universal answers.[23]

Despite frequent moves[24] he wrote all his major work during his 20-plus years in the Netherlands, where he managed to revolutionize mathematics and philosophy.[25] In 1633, Galileo was condemned by the Catholic Church, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish Treatise on the World, his work of the previous four years. Nevertheless, in 1637 he published part of this work in three essays: Les Météores (The Meteors), La Dioptrique (Dioptrics) and La Géométrie (Geometry), preceded by an introduction, his famous Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method), also meant for women. In it Descartes lays out four rules of thought, meant to ensure that our knowledge rests upon a firm foundation.

"The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt."

Descartes continued to publish works concerning both mathematics and philosophy for the rest of his life. In 1641 he published a metaphysics work, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), written in Latin and thus addressed to the learned. It was followed, in 1644, by Principia Philosophiæ (Principles of Philosophy), a kind of synthesis of the Meditations and the Discourse. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began (through Alfonso Polloti, an Italian general in Dutch service) a long correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, devoted mainly to moral and psychological subjects. Connected with this correspondence, in 1649 he published Les Passions de l'âme (Passions of the Soul), that he dedicated to the Princess. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the Louis XIV, though it was never paid.[26]

A French translation of Principia Philosophiæ, prepared by Abbot Claude Picot, was published in 1647. This edition Descartes dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. In the preface Descartes praised true philosophy as a means to attain wisdom. He identifies four ordinary sources to reach wisdom, and finally says that there is a fifth, better and more secure, consisting in the search for first causes.[27]

Death

René Descartes was a guest at the house of Pierre Chanut, living on Västerlånggatan, less than 500 meters from Tre Kronor in Stockholm. (There Chanut and Descartes made observations with a Torricellian barometer, a tube with mercury. Challenging Blaise Pascal Descartes took the first set of barometric readings in Stockholm to see if atmospheric pressure could be used in forecasting the weather.[28][29]) Descartes had been invited by Christina, Queen of Sweden to organize a new scientific academy, and tutor her in his ideas about love. She was interested in and stimulated Descartes to publish the "Passions of the Soul", a work based on his correspondence with Princess Elisabeth.[30] The lessons appear to have begun after her birthday, early in the morning at 5 a.m in her hardly heated and draughty castle and three times a week. Soon it became clear they did not like each other; she did not like his mechanical philosophy, he did not appreciate her interest for Ancient Greek. On 15 January Descartes had seen Christina only four or five times. On 1 February Descartes caught a cold. His illness quickly turned into a serious respiratory infection. The cause of death on 11 February 1650 was according to Chanut pneumonia, according to the doctor Van Wullen who was not allowed to bleed him, peripneumonia.[31] (The winter seems to have been mild,[32] except for the second half of January) which was harsh as described by Descartes himself. "This remark was probably intended to be as much Descartes' take on the intellectual climate as it was about the weather."[30]

In 1991 E. Pies, a German scholar, published a book questioning this account, based on a letter by Van Wullen, and more arguments against its veracity have been raised since.[33] Descartes might have been assassinated[34][35] as he asked the doctor for an emetic: wine mixed with tobacco[36] and seems to have died without saying a word.

The tomb of Descartes (middle, with detail of the inscription), in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard used mainly for orphans in Adolf Fredriks kyrka in Stockholm. His manuscripts came in the possession of Claude Clerselier, Chanut's brother-in-law, and "a devout Catholic who has begun the process of turning Descartes into a saint by cutting, adding and publishing his letters selectively."[37] In 1663, the Pope placed his works on the Index of Prohibited Books. In 1666 his remains were taken to France and buried in the Saint-Étienne-du-Mont. In 1671 Louis XIV prohibited all the lectures in Cartesianism. Although the National Convention in 1792 had planned to transfer his remains to the Panthéon, he was reburied in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1819, missing a finger and the skull.[38]

Religious beliefs

The religious beliefs of René Descartes have been rigorously debated within scholarly circles. He claimed to be a devout Catholic, saying that one of the purposes of the Meditations was to defend the Christian faith, although his reasoning for being Catholic could be because he "preferred to avoid all collision with ecclesiastical authority."[2] However, in his own era, Descartes was accused of harboring secret deist or atheist beliefs. His contemporary Blaise Pascal said that "I cannot forgive Descartes; in all his philosophy, Descartes did his best to dispense with God. But Descartes could not avoid prodding God to set the world in motion with a snap of his lordly fingers; after that, he had no more use for God."[39] Stephen Gaukroger's biography of Descartes reports that "he had a deep religious faith as a Catholic, which he retained to his dying day, along with a resolute, passionate desire to discover the truth."[40] The debate continues whether Descartes was a Catholic/Christian apologist, or a deist/atheist concealed behind pious sentiments who placed the world on a mechanistic framework, within which only man could freely move due to the grace of will granted by God.[26]Philosophical work

Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker to emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences.[41] For him the philosophy was a thinking system that embodied all knowledge, and expressed it in this way:[42]| “ | Thus, all Philosophy is like a tree, of which Metaphysics is the root, Physics the trunk, and all the other sciences the branches that grow out of this trunk, which are reduced to three principals, namely, Medicine, Mechanics, and Ethics. By the science of Morals, I understand the highest and most perfect which, presupposing an entire knowledge of the other sciences, is the last degree of wisdom. | ” |

In his Discourse on the Method, he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called hyperbolical/metaphysical doubt, also sometimes referred to as methodological skepticism: he rejects any ideas that can be doubted, and then reestablishes them in order to acquire a firm foundation for genuine knowledge.[43]

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: thought exists. Thought cannot be separated from me, therefore, I exist (Discourse on the Method and Principles of Philosophy). Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum (English: "I think, therefore I am"). Therefore, Descartes concluded, if he doubted, then something or someone must be doing the doubting, therefore the very fact that he doubted proved his existence. "The simple meaning of the phrase is that if one is skeptical of existence, that is in and of itself proof that he does exist."[44]

Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists because he thinks. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously been unreliable. So Descartes determines that the only indubitable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is what he does, and his power must come from his essence. Descartes defines "thought" (cogitatio) as "what happens in me such that I am immediately conscious of it, insofar as I am conscious of it". Thinking is thus every activity of a person of which the person is immediately conscious.[45]

To further demonstrate the limitations of these senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as the Wax Argument. He considers a piece of wax; his senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. When he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: it is still the same piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Therefore, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he should put aside the senses. He must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

| “ | And so something that I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgment which is in my mind. | ” |

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and instead admitting only deduction as a method. In the third and fifth Meditation, he offers an ontological proof of a benevolent God (through both the ontological argument and trademark argument). Because God is benevolent, he can have some faith in the account of reality his senses provide him, for God has provided him with a working mind and sensory system and does not desire to deceive him. From this supposition, however, he finally establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception. In terms of epistemology therefore, he can be said to have contributed such ideas as a rigorous conception of foundationalism and the possibility that reason is the only reliable method of attaining knowledge. He, nevertheless, was very much aware that experimentation was necessary in order to verify and validate theories.[42]

Descartes also wrote a response to External world scepticism. He argues that sensory perceptions come to him involuntarily, and are not willed by him. They are external to his senses, and according to Descartes, this is evidence of the existence of something outside of his mind, and thus, an external world. Descartes goes on to show that the things in the external world are material by arguing that God would not deceive him as to the ideas that are being transmitted, and that God has given him the "propensity" to believe that such ideas are caused by material things. He gave reasons for thinking that waking thoughts are distinguishable from dreams, and that one's mind cannot have been "hijacked" by an evil demon placing an illusory external world before one's senses.

Dualism

Descartes in his Passions of the Soul and The Description of the Human Body suggested that the body works like a machine, that it has material properties. The mind (or soul), on the other hand, was described as a nonmaterial and does not follow the laws of nature. Descartes argued that the mind interacts with the body at the pineal gland. This form of dualism or duality proposes that the mind controls the body, but that the body can also influence the otherwise rational mind, such as when people act out of passion. Most of the previous accounts of the relationship between mind and body had been uni-directional.Descartes suggested that the pineal gland is "the seat of the soul" for several reasons. First, the soul is unitary, and unlike many areas of the brain the pineal gland appeared to be unitary (though subsequent microscopic inspection has revealed it is formed of two hemispheres). Second, Descartes observed that the pineal gland was located near the ventricles. He believed the cerebrospinal fluid of the ventricles acted through the nerves to control the body, and that the pineal gland influenced this process. Sensations delivered by the nerves to the pineal, he believed, caused it to vibrate in some sympathetic manner, which in turn gave rise to the emotions and caused the body to act.[26] Cartesian dualism set the agenda for philosophical discussion of the mind–body problem for many years after Descartes' death.[46]

In present day discussions on the practice of animal vivisection, it is normal to consider Descartes as an advocate of this practice, as a result of his dualistic philosophy. Some of the sources say that Descartes denied the animals could feel pain, and therefore could be used without concern.[47] Other sources consider that Descartes denied that animals had reason or intelligence, but did not lack sensations or perceptions, but these could be explained mechanistically.[48]

Descartes' moral philosophy

For Descartes, ethics was a science, the highest and most perfect of them. Like the rest of the sciences, ethics had its roots in metaphysics.[42] In this way he argues for the existence of God, investigates the place of man in nature, formulates the theory of mind-body dualism, and defends free will. However, as he was a convinced rationalist, Descartes clearly states that reason is sufficient in the search for the goods that we should seek, and virtue consists in the correct reasoning that should guide our actions. Nevertheless, the quality of this reasoning depends on knowledge, because a well-informed mind will be more capable of making good choices, and it also depends on mental condition. For this reason he said that a complete moral philosophy should include the study of the body. He discussed this subject in the correspondence with Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, and as a result wrote his work The Passions of the Soul, that contains a study of the psychosomatic processes and reactions in man, with an emphasis on emotions or passions.[49]Humans should seek the sovereign good that Descartes, following Zeno, identifies with virtue, as this produces a solid blessedness or pleasure. For Epicurus the sovereign good was pleasure, and Descartes says that in fact this is not in contradiction with Zeno's teaching, because virtue produces a spiritual pleasure, that is better than bodily pleasure. Regarding Aristotle's opinion that happiness depends on the goods of fortune, Descartes does not deny that this good contributes to happiness, but remarks that they are in great proportion outside one's own control, whereas one's mind is under one's complete control.[49]

The moral writings of Descartes came at the last part of his life, but earlier, in his Discourse on Method he adopted three maxims to be able to act while he put all his ideas into doubt. This is known as his "Provisional Morals".

Historical impact

Emancipation from Church doctrine

Descartes has been often dubbed as the father of modern Western philosophy, the philosopher that with his skeptic approach has profoundly changed the course of Western philosophy and set the basis for modernity.[7][50] The first two of his Meditations on First Philosophy, those that formulate the famous methodic doubt, represent the portion of Descartes' writings that most influenced modern thinking.[51] It has been argued that Descartes himself didn't realize the extent of his revolutionary gesture.[52] In shifting the debate from "what is true" to "of what can I be certain?," Descartes shifted the authoritative guarantor of truth from God to humanity. (While the traditional concept of "truth" implies an external authority, "certainty" instead relies on the judgment of the individual.) In an anthropocentric revolution, the human being is now raised to the level of a subject, an agent, an emancipated being equipped with autonomous reason. This was a revolutionary step that posed the basis of modernity, the repercussions of which are still ongoing: the emancipation of humanity from Christian revelational truth and Church doctrine, a person who makes his own law and takes his own stand.[53][54][55] In modernity, the guarantor of truth is not God anymore but human beings, each of whom is a "self-conscious shaper and guarantor" of their own reality.[56][57] In that way, each person is turned into a reasoning adult, a subject, and agent,[56] as opposed to a child obedient to God. This change in perspective was characteristic of the shift from the Christian medieval period to the modern period; that shift had been anticipated in other fields, and now Descartes was giving it a formulation in the field of philosophy.[56][58]This anthropocentric perspective, establishing human reason as autonomous, provided the basis for the Enlightenment's emancipation from God and the Church. It also provided the basis for all subsequent anthropology.[59] Descartes' philosophical revolution is sometimes said to have sparked modern anthropocentrism and subjectivism.[7][60][61][62]

Mathematical legacy

One of Descartes' most enduring legacies was his development of Cartesian or analytic geometry, which uses algebra to describe geometry. He "invented the convention of representing unknowns in equations by x, y, and z, and knowns by a, b, and c". He also "pioneered the standard notation" that uses superscripts to show the powers or exponents; for example, the 4 used in x4 to indicate squaring of squaring.[63][64] He was first to assign a fundamental place for algebra in our system of knowledge, and believed that algebra was a method to automate or mechanize reasoning, particularly about abstract, unknown quantities. European mathematicians had previously viewed geometry as a more fundamental form of mathematics, serving as the foundation of algebra. Algebraic rules were given geometric proofs by mathematicians such as Pacioli, Cardan, Tartaglia and Ferrari. Equations of degree higher than the third were regarded as unreal, because a three-dimensional form, such as a cube, occupied the largest dimension of reality. Descartes professed that the abstract quantity a2 could represent length as well as an area. This was in opposition to the teachings of mathematicians, such as Vieta, who argued that it could represent only area. Although Descartes did not pursue the subject, he preceded Leibniz in envisioning a more general science of algebra or "universal mathematics," as a precursor to symbolic logic, that could encompass logical principles and methods symbolically, and mechanize general reasoning.[65]

Descartes' work provided the basis for the calculus developed by Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, who applied infinitesimal calculus to the tangent line problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics.[66] His rule of signs is also a commonly used method to determine the number of positive and negative roots of a polynomial.

Descartes discovered an early form of the law of conservation of mechanical momentum (a measure of the motion of an object), and envisioned it as pertaining to motion in a straight line, as opposed to perfect circular motion, as Galileo had envisioned it. He outlined his views on the universe in his Principles of Philosophy.

Descartes also made contributions to the field of optics. He showed by using geometric construction and the law of refraction (also known as Descartes' law or more commonly Snell's law) that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42 degrees (i.e., the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow's centre is 42°).[67] He also independently discovered the law of reflection, and his essay on optics was the first published mention of this law.[68]

Contemporary reception

Although Descartes was well known in academic circles towards the end of his life, the teaching of his works in schools was controversial. Henri de Roy (Henricus Regius, 1598–1679), Professor of Medicine at the University of Utrecht, was condemned by the Rector of the University, Gijsbert Voet (Voetius), for teaching Descartes' physics.[69]Writings

- 1618. Musicae Compendium. A treatise on music theory and the aesthetics of music written for Descartes' early collaborator, Isaac Beeckman (first posthumous edition 1650).

- 1626–1628. Regulae ad directionem ingenii (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). Incomplete. First published posthumously in Dutch translation in 1684 and in the original Latin at Amsterdam in 1701 (R. Des-Cartes Opuscula Posthuma Physica et Mathematica). The best critical edition, which includes the Dutch translation of 1684, is edited by Giovanni Crapulli (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1966).

- 1630–1631. La recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle (The Search for Truth) unfinished dialogue published in 1701.

- 1630–1633. Le Monde (The World) and L'Homme (Man). Descartes' first systematic presentation of his natural philosophy. Man was published posthumously in Latin translation in 1662; and The World posthumously in 1664.

- 1637. Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method). An introduction to the Essais, which include the Dioptrique, the Météores and the Géométrie.

- 1637. La Géométrie (Geometry). Descartes' major work in mathematics. There is an English translation by Michael Mahoney (New York: Dover, 1979).

- 1641. Meditationes de prima philosophia (Meditations on First Philosophy), also known as Metaphysical Meditations. In Latin; a French translation, probably done without Descartes' supervision, was published in 1647. Includes six Objections and Replies. A second edition, published the following year, included an additional objection and reply, and a Letter to Dinet.

- 1644. Principia philosophiae (Principles of Philosophy), a Latin textbook at first intended by Descartes to replace the Aristotelian textbooks then used in universities. A French translation, Principes de philosophie by Claude Picot, under the supervision of Descartes, appeared in 1647 with a letter-preface to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia.

- 1647. Notae in programma (Comments on a Certain Broadsheet). A reply to Descartes' one-time disciple Henricus Regius.

- 1648. La description du corps humaine (The Description of the Human Body). Published posthumously by Clerselier in 1667.

- 1648. Responsiones Renati Des Cartes... (Conversation with Burman). Notes on a Q&A session between Descartes and Frans Burman on 16 April 1648. Rediscovered in 1895 and published for the first time in 1896. An annotated bilingual edition (Latin with French translation), edited by Jean-Marie Beyssade, was published in 1981 (Paris: PUF).

- 1649. Les passions de l'âme (Passions of the Soul). Dedicated to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate.

- 1657. Correspondance. Published by Descartes' literary executor Claude Clerselier. The third edition, in 1667, was the most complete; Clerselier omitted, however, much of the material pertaining to mathematics.