A population decline (or depopulation) in humans is any great reduction in a human population caused by events such as long-term demographic trends, as in sub-replacement fertility, urban decay, white flight or rural flight, or due to violence, disease, or other catastrophes.[1]

Causes

A reduction over time in a region's population can be caused by several factors including sub-replacement fertility (along with limited immigration), heavy emigration, disease, famine, and war. History is replete with examples of large-scale depopulations. Many wars, for example, have been accompanied by significant depopulations. Before the 20th century, population decline was mostly observed due to disease, starvation or emigration. The Black Death in Europe, the arrival of Old World diseases to the Americas, the tsetse fly invasion of the Waterberg Massif in South Africa, and the Great Irish Famine all caused sizable population declines. In modern times, the AIDS epidemic caused declines in the population of some African countries. Less frequently, population declines are caused by genocide or mass execution; for example, in the 1970s, the population of Cambodia declined because of wide-scale executions by the Khmer Rouge.Underpopulation

Sometimes the term underpopulation is applied to a specific economic system. It does not refer to carrying capacity, and is not a term in opposition to overpopulation, which deals with the total possible population that can be sustained by available food, water, sanitation and other infrastructure. "Underpopulation" is usually defined as a state in which a country's population has declined too much to support its current economic system. Thus the term has nothing to do with the biological aspects of carrying capacity, but is an economic term employed to imply that the transfer payment schemes of some developed countries might fail once the population declines to a certain point. An example would be if retirees were supported through a social security system which does not invest savings, and then a large emigration movement occurred. In this case, the younger generation may not be able to support the older generation.Changing trends

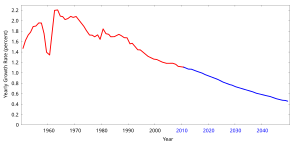

Since the dire predictions of coming population overshoot in the 1960s and 70s, and many other social changes, more couples in many countries have tended to choose to have fewer children. Today, emigration, sub-replacement fertility and high death rates in the former Soviet Union and its former allies are the principal reasons for that region's population decline.[citation needed] However, governments can influence the speed of the decline, including measures to halt, slow or suspend decline. Such measures include pro-birth policies and subsidies, media influence, immigration, bolstering healthcare and laws aimed at reducing death rates. Some of these have been applied in Russia, Armenia, and many Western European nations which have used immigration and other policies to suspend or slow population decline. Therefore, although the long-term trend may be for greater population decline, short term trends may slow the decline or even reverse it, creating seemingly conflicting statistical data. A great example of changing trends occurring over a century is Ireland.Interpretation of statistical data

Statistical data, especially those comparing only two sets of figures, can be misleading and may require careful interpretation. For instance a nation's population could have been increasing, but a one-off event could have resulted in a short-term decline; or vice versa. Nations can acquire territory or lose territory, and groups of people can acquire or lose citizenship, e.g. stateless persons, indigenous people, and illegal immigrants or long-stay foreign residents. Political instability can make it difficult to conduct a census in certain regions. Further, a country's population could rise in summer and decline in winter as deaths increase in winter in cold regions; a long census interval could show a rise in population when the population has already tipped into decline.Contemporary decline by country

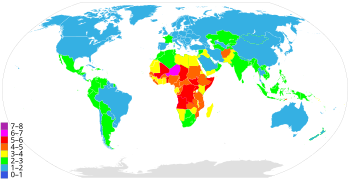

A number of nations today are declining in population: this is occurring in a region stretching from North Asia (Japan) through Eastern Europe, including Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Georgia, and into Central and Western Europe, including Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, and now Greece, Italy and Portugal, in addition to Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. Countries rapidly approaching population declines in the 2020-25 period include Spain, Germany, andSlovenia.Russia also faces long-term population decline, although the trend has been stalled through a reversal of stagnant birth rates.

AIDS has played some role in temporary population decline; however, available data suggest that, even with high AIDS mortality, fertility rates in Africa are high enough for the overpopulation trend to continue.[2] AIDS has contributed to a population explosion in Africa as money from fertility reduction programs was redirected into the HIV/AIDS crisis; African fertility rates have actually increased in the past two decades, and population has grown by over 50%.[3]

Below are some examples of countries that are experiencing population decline. The term population used here is based on the de facto definition of population, which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship, except for refugees not permanently settled in the country of asylum, who are generally considered part of the population of the country of origin. This means that population growth in this table includes net changes from immigration and emigration. For a table of natural population changes, see List of countries by natural increase.

| Country | Population | Avg annual rate of population change

(%) 2015 - 20[4] |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9,505,000 | -0.15 | low birth rate, emigration, population increased in 2014 due to positive net migration rate | |

| 3,350,000 | -0.22 | low birth rate, emigration, Bosnian War | |

| 7,050,000 | -0.67 | low birth rate, high death rate, high rate of abortions, emigration, a relatively high level of emigration of young people and a low level of immigration[5] | |

| 4,154,000 | -0.58 | low birth rate, emigration, War in Croatia, difference in statistical methods[6] | |

| 1,319,000 | -0.23 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 82,665,000 |

+0.20 | low birth rate, population increased in 2012, 2013, and 2014 due to positive net migration rate | |

| 11,184,000 | -0.21 | low birth rate, economic crisis, emigration | |

| 9,798,000 | -0.34 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 60, 494, 000 | -0.13 | low birth rate, economic crisis, population increased in 2012, 2013, and 2014 due to positive net migration rate | |

| 126,714,000 | -0.23 | low birth rate and a low level of immigration | |

| 1,940,000 | -1.03 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 2,800,000 | -0.55 | high death rate, low birth rate, emigration | |

| 2,998,000 | -0.24 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 38,422,000 | -0.17 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 10,291,000 | -0.39 | low birth rate, economic crisis, emigration | |

| 3,337,000 | -0.13 | low birth rate, economic crisis, emigration to the U.S. mainland | |

| 19,638,000 | -0.50 | low birth rate, high death rate, high rate of abortion, emigration | |

| 146,880,613 |

-0.01 | high death rate, low birth rate, high rate of abortions, emigration and a low level of immigration until recently[7] Population increased slightly since 2014 due to positive natural change and positive net migration rate | |

| 7,040,000 | -0.34 | low birth rate, emigration | |

| 46,698,000 | +0.03 | low birth rate, economic crisis | |

| 43,001,000 | -0.49 | Same as Russia + declining births, emigration | |

| Georgia | 3,718,000 | -0.27 | |

| World | 741,447,000 | +1.09 | |

| Europe | 7.62 billion | +0.07 |

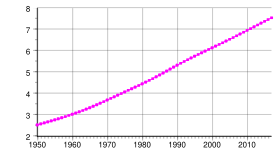

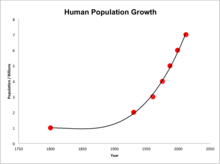

Long-term trends

A long-term population decline is typically caused by sub-replacement fertility, coupled with a net immigration rate that fails to compensate the excess of deaths over births.[8] A long-term decline is accompanied by population aging and creates an increase in the ratio of retirees to workers and children.[8] When a sub-replacement fertility rate remains constant, population decline accelerates over the long term,[8] however short term baby booms, healthcare improvements, among other factors created can cause flip-flops of trends. Population decline trends have seen long term reversals in places such as Russia, Germany, Ireland, and the UK, the latter two seeing declines as early as the 1970s, yet the UK now is growing more rapidly than any year since it first tipped into declines.[9] In spite of more recent declines, it is very uncommon for population to have dipped under the levels of the early post-world war 2 years. Bulgaria and Latvia are the only nations with a net population decline since 1950, and half of all nations worldwide have more than quadrupled their populations.[10] UAE's current population is over 120 times that of 1950, and Qatar's population has grown over 80 times the 1950s level.[10]United States

Despite ever increasing population in the United States, some American municipalities (city limits) have shrunk due to white flight and urban decay. Detroit is the most notable of a number of cities with population smaller than in 1950 and whose population shrinkage has been the most dramatic; Detroit's population was almost 1.85 million as of the 1950 census but has plummeted to 677,000 as of 2015, with the most rapid decline occurring between 2000 and 2010.Other American cities whose populations have shrunk substantially since the 1950s – although some have begun to grow again – include New Orleans; St. Louis; Buffalo, New York; Philadelphia; Chicago; Cleveland; Pittsburgh; and Wilmington, Delaware.

Japan

Though Japan's population has been predicted to decline for years, and its monthly and even annual estimates have shown a decline in the past, the 2010 census result figure was slightly higher, at just above 128 million,[11] than the 2005 census. Factors implicated in the higher figures were more Japanese returnees than expected as well as changes to the methodology of data collection. The official count put the population as of Oct 1, 2015, at 127.1 million, down by 947,000 or 0.7% from the previous census in 2010.[12][13] The gender ratio is increasingly skewed; some 106 women per 100 men live in Japan. The total population is still 52% above 1950 levels.[14] In 2013, Japan's population fell by a record-breaking 244,000.[15] The Tohoku region in Japan now has fewer people than in 1950.Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics

Population is falling due to health factors and low replacement, as well as emigration of ethnic Russians to Russia. Exceptions to this rule are in those ex-Soviet states that have a Muslim majority (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan), where high birth rates are traditional. Much of Eastern Europe has lost population due to migration to Western Europe. In Eastern Europe and Russia, natality fell abruptly after the end of the Soviet Union, and death rates generally rose. Together these nations occupy over 21,000,000 square kilometres (8,000,000 sq mi) and are home to over 400 million people (less than six percent of the world population), but if current trends continue, more of the developed world and some of the developing world could join this trend.Albania

Albania's population in 1989 recorded 3,182,417 people, the largest for any census. Since then, its population declined to an estimated 2,893,005 in Jan 2015.[16] This represents a decrease of 10% in total population since the peak census figure.Armenia

Armenia's population peaked at 3,604,000 in 1991[17] and declined to 3,010,600 in the Jan 2015 state statistical estimate.[18] This represents a 19.7% decrease in total population since the peak census figure.Belarus

Belarus' population peaked at 10,151,806 in 1989 Census, and declined to 9,480,868 as of 2015 as estimated by the state statistical service.[19] This represents a 7.1% decline since the peak census figure.Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina's population is thought to have peaked at 4,377,033 in 1991 Census, shortly before splitting from Yugoslavia before the ensuing war. The latest census of 2013 reported 3,791,622 people.[20] This represents a 15.4% decline since the peak census figure.Bulgaria

Bulgaria's population declined from a peak of 9,009,018 in 1989 and since 2001, has lost yet another 600,000 people, according to 2011 census preliminary figures to no more than 7.3 million.,[21] further down to 7,245,000. This represents a 24.3% decrease in total population since the peak, and a -0.82% annual rate in the last 10 years.Croatia

Croatia's population declined from 4,784,265 in 1991[22] to 4,456,096[23] (by old statistical method) of which 4,284,889[24] are permanent residents (by new statistical method), in 2011, a decline of 8% (11,5% by the new definition of permanent residency in 2011 census). The main reasons for the decline since 1991 are: low birth rates, emigration and War in Croatia. From 2001 and 2011 main reason for the drop in population is due to a difference in definition of permanent residency used in census' till 2001 (census' of 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001) and the one used in 2011.[6]Estonia

In the last Soviet census of 1989, it had a population of 1,565,662, which was close to its peak population.[25] The state statistics reported an estimate of 1,314,370 for 2016.[25] This represents a 19.2% decline since the peak census figure.Georgia

In the last Soviet census of 1989, it had a population of 5,400,841, which was close to its peak population.[26] The state statistics reported an estimate of 4,010,000 for 2014 Census, which includes estimated numbers for quasi-independent Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[26] This represents a 25.7% decline since the peak census figure, but nevertheless somewhat higher than the 1950 population.Latvia

When Latvia split from the Soviet Union, it had a population of 2,666,567, which was close to its peak population.[27] The latest census recorded a population of 2,067,887 in 2011, while the state statistics reported an estimate of 1,986,086 for 2015.[27] This represents a 25.5% decline since the peak census figure, only one of 2 nations worldwide falling below 1950 levels. The decline is caused by both a negative natural population growth (more deaths than births) and a negative net migration rate.Lithuania

When Lithuania split from the Soviet Union, it had a population of 3.7 million, which was close to its peak population.[28] The latest census recorded a population of 3.05 million in 2011, down from 3.4 million in 2001.,[28] further falling to 2,988,000 in September 1, 2012.[29] This represents a 23.8% decline since the peak census figure, and some 13.7% since 2001.Ukraine

Ukraine census in 1989 resulted in 51,452,034 people,[30] Ukraine's own estimates show a peak of 52,244,000 people in 1993,[31] however this number has plummeted to 45,439,822 as of Dec 1, 2013.,[32] having lost Crimean territory and experienced war, the population has plunged to 42,981,850 as of August 2014.[33] This represents a 19.7% decrease in total population since the peak figure, but 16.8% above the 1950 population even without Crimea.[14] Its absolute total decline (9,263,000) since its peak population is the highest of all nations; this includes loss of territory and heavy net emigration. Eastern Ukraine may yet lose many Russian speaking citizens due to new Russian citizenship law.[34]Hungary

Hungary's population peaked in 1980, at 10,709,000,[35] and has continued its decline to under 10 million as of August 2010.[36] This represents a decline of 7.1% since its peak; however, compared to neighbors situated to the East, Hungary peaked almost a decade earlier yet the rate has been far more modest, averaging -0.23% a year over the period.Romania

Romania's 1991 census showed 23,185,084 people, and the October 2011 census recorded 20,121,641 people, while the state statistical estimate for 2014 is 19,947,311.[37] This represents a decrease of 16.2% since the historical peak in 1991.Serbia

Serbia recorded a peak census population of 7,576,837 in 1991, falling to 7,186,862 in the 2011 census.[38] That represents a decline of 5.1% since its peak census figure.Halted declines

Russia

The decline in Russia's total population is among the largest in numbers, but not in percentage. After having peaked at 148,689,000 in 1991, the population then decreased, falling to 142,737,196 by 2008.[39] This represents a 4.0% decrease in total population since the peak census figure. Still, the Russian government estimates an increase in the population to 143,500,000 in 2013. This recent trend can be attributed to a lower death rate, higher birth rate, and continued immigration, mostly from Ukraine and Armenia. It is some 40% above the 1950 population.[14]Germany

In Germany a decades-long tendency to population decline has been offset by waves of immigration. The 2011 national census recorded a population of 80.2 million people.[40] At the end of 2012 it had risen to 82.0 million according to federal estimates.[41] This represents about 14% increase over 1950.[42]Ireland

In the current area of the Republic of Ireland, the population has fluctuated dramatically. The population of Ireland was 8 million in 1841, but it dropped due to the Irish famine and later emigration. The population of the Republic of Ireland hit bottom at 2.8 million in the 1961 census, but it then rose and in 2011 it was 4.58 million.Declines within race or ethnicity

Some large (and even majority groups within a population) have shown an overall decline in numbers, while the total population increased. Such is the case in California, where the Non-Hispanic Whites population declined from 15.8 million to 14.95 million,[43] meanwhile the total population increased from 33 million to over 37 million, from 2000 to 2010 censuses. Singapore also has one of the world's lowest birthrate. The ratio of "original" Singaporeans towards "immigrant" Singaporeans and migrants continues to erode, with originals decreasing in absolute figures, despite the country planning to increase the population by over 20% in coming years.Economic consequences

Old man at a nursing home in Norway.

The effects of a declining population can be adverse for an economy which has borrowed extensively for repayment by younger generations. However, population growth is also becoming increasingly unsustainable due to global warming, which is expected to have harsh economic consequences. Economically declining populations are thought to lead to deflation[citation needed], which has a number of effects. However, Russia, whose economy has been rapidly growing (8.1% in 2007) even as its population is shrinking, currently has high inflation (12% as of late 2007).[44] For an agricultural or mining economy the average standard of living in a declining population, at least in terms of material possessions, will tend to rise as the amount of land and resources per person will be higher.

But for many industrial economies, the opposite might be true as those economies often thrive on mortgaging the future by way of debt and retirement transfer payments that originally assumed rising tax revenues from a continually expanding population base (i.e. there would be fewer taxpayers in a declining population). However, standard of living does not necessarily correlate with quality of life, which may increase as the population declines due to presumably reduced pollution and consumption of natural resources, and the decline of social pressures and overutilization of resources that can be linked to overpopulation. There may also be reduced pressure on infrastructure, education, and other services as well.

The period immediately after the Black Death, for instance, was one of great prosperity, as people had inheritances from many different family members. However, that situation was not comparable, as it did not have a continually declining population, but rather a sudden shock, followed by population increase. Predictions of the net economic (and other) effects from a slow and continuous population decline (e.g. due to low fertility rates) are mainly theoretical since such a phenomenon is a relatively new and unprecedented one.

A declining population due to low fertility rates will also be accompanied by population ageing which can contribute problems for a society. This can adversely affect the quality of life for the young as an increased social and economic pressure in the sense that they have to increase per-capita output in order to support an infrastructure with costly, intensive care for the oldest among their population. The focus shifts away from the planning of future families and therefore further degrades the rate of procreation. The decade-long economic malaise of Japan and Germany in the 1990s and early 2000s is often linked to these demographic problems, though there were also several other causes. The worst-case scenario is a situation where the population falls too low a level to support a current social welfare economic system, which is more likely to occur with a rapid decline than with a more gradual one.

The economies of both Japan and Germany both went into recovery around the time their populations just began to decline (2003–2006). In other words, both the total and per capita GDP in both countries grew more rapidly after 2005 than before. Russia's economy also began to grow rapidly from 1999 onward, even though its population has been shrinking since 1992-93 (the decline is now decelerating).[45] In addition, many Eastern European countries have been experiencing similar effects to Russia. Such renewed growth calls into question the conventional wisdom that economic growth requires population growth, or that economic growth is impossible during a population decline. However, it may be argued that this renewed growth is in spite of population decline rather than because of it, and economic growth in these countries would potentially be greater if they were not undergoing such demographic decline. For example, Russia has become quite wealthy selling fossil fuels such as oil, which are now high-priced, and in addition, its economy has expanded from a very low nadir due to the economic crisis of the late 1990s. And although Japan and Germany have recovered somewhat from having been in a deflationary recession and stagnation, respectively, for the past decade, their recoveries seem to have been quite tepid. Both countries fell into the global recession of 2008–2009, but are now recovering once again, being among the first countries to recover.[46][47]

In a country with a declining population, the growth of GDP per capita is higher than the growth of GDP. For example, Japan has a higher growth per capita than the United States, even though the U.S. GDP growth is higher than Japan's.[48] Even when GDP growth is zero or negative, the GDP growth per capita can still be positive (by definition) if the population is shrinking faster than the GDP.

A declining population (regardless of the cause) can also create a labor shortage, which can have a number of positive and negative effects. While some labor-intensive sectors of the economy may be hurt if the shortage is severe enough, others may adequately compensate by increased outsourcing or automation. Initially, the labor participation rates (which are low in many countries) can also be increased to temporarily reduce or delay the shortage. On the positive side, such a shortage increases the demand for labor, which can potentially result in a reduced unemployment rate as well as higher wages. Conversely, a high population means labor is in plentiful supply, which usually means wages will be lower. This is seen in countries like China and India.

Analysing data for 40 countries, Lee et al. show that fertility well above replacement and population growth would typically be most beneficial for government budgets. However, fertility near replacement and population stability would be most beneficial for standards of living when the analysis includes the effects of age structure on families as well as governments. And fertility moderately below replacement and population decline would maximize standards of living when the cost of providing capital for a growing labour force is taken into account.[49]

A smaller national population can also have geo-strategic effects, but the correlation between population and power is a tenuous one. Technology and resources often play more significant roles.

National efforts to reverse declining populations

Many European countries, including France, Italy, Germany and Poland, have offered some combination of bonuses and monthly payments to families.Paid maternity and paternity leave policies can also be used as an incentive. Sweden built up an extensive welfare state from the 1930s and onward, partly as a consequence of the debate following Crisis in the Population Question, published in 1934. Today, Sweden has extensive parental leave where parents are entitled to share 16 months paid leave per child, the cost divided between both employer and State.