| Amazon rainforest | |

| Forest | |

|

Amazon rainforest, near Manaus, Brazil.

| |

| Countries | Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, France (French Guiana) |

|---|---|

| Part of | South America |

| River | Amazon River |

| Area | 5,500,000 km2 (2,123,562 sq mi) |

|

Map of the Amazon rainforest ecoregions as delineated by the WWF. The yellow line approximately encloses the Amazon drainage basin. National boundaries are shown in black.

(Satellite image from NASA) | |

Etymology

The name Amazon is said to arise from a war Francisco de Orellana fought with the Tapuyas and other tribes. The women of the tribe fought alongside the men, as was their custom.[3] Orellana derived the name Amazonas from the Amazons of Greek mythology, described by Herodotus and Diodorus.[3]History

Natural

Aerial view of the Amazon rainforest, near Manaus

The rainforest likely formed during the Eocene era. It appeared following a global reduction of tropical temperatures when the Atlantic Ocean had widened sufficiently to provide a warm, moist climate to the Amazon basin. The rainforest has been in existence for at least 55 million years, and most of the region remained free of savanna-type biomes at least until the current ice age, when the climate was drier and savanna more widespread.[4][5]

Following the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, the extinction of the dinosaurs and the wetter climate may have allowed the tropical rainforest to spread out across the continent. From 66–34 Mya, the rainforest extended as far south as 45°. Climate fluctuations during the last 34 million years have allowed savanna regions to expand into the tropics. During the Oligocene, for example, the rainforest spanned a relatively narrow band. It expanded again during the Middle Miocene, then retracted to a mostly inland formation at the last glacial maximum.[6] However, the rainforest still managed to thrive during these glacial periods, allowing for the survival and evolution of a broad diversity of species.[7]

Aerial view of the Amazon rainforest.

During the mid-Eocene, it is believed that the drainage basin of the Amazon was split along the middle of the continent by the Purus Arch. Water on the eastern side flowed toward the Atlantic, while to the west water flowed toward the Pacific across the Amazonas Basin. As the Andes Mountains rose, however, a large basin was created that enclosed a lake; now known as the Solimões Basin. Within the last 5–10 million years, this accumulating water broke through the Purus Arch, joining the easterly flow toward the Atlantic.[8][9]

There is evidence that there have been significant changes in Amazon rainforest vegetation over the last 21,000 years through the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and subsequent deglaciation. Analyses of sediment deposits from Amazon basin paleolakes and from the Amazon Fan indicate that rainfall in the basin during the LGM was lower than for the present, and this was almost certainly associated with reduced moist tropical vegetation cover in the basin.[10] There is debate, however, over how extensive this reduction was. Some scientists argue that the rainforest was reduced to small, isolated refugia separated by open forest and grassland;[11] other scientists argue that the rainforest remained largely intact but extended less far to the north, south, and east than is seen today.[12] This debate has proved difficult to resolve because the practical limitations of working in the rainforest mean that data sampling is biased away from the center of the Amazon basin, and both explanations are reasonably well supported by the available data.

Sahara Desert dust windblown to the Amazon

More than 56% of the dust fertilizing the Amazon rainforest comes from the Bodélé depression in Northern Chad in the Sahara desert. The dust contains phosphorus, important for plant growth. The yearly Sahara dust replaces the equivalent amount of phosphorus washed away yearly in Amazon soil from rains and floods.[13] Up to 50 million tonnes of Sahara dust per year are blown across the Atlantic Ocean.NASA's CALIPSO satellite has measured the amount of dust transported by wind from the Sahara to the Amazon: an average 182 million tons of dust are windblown out of the Sahara each year, at 15 degrees west longitude, across 1,600 miles (2,600 km) over the Atlantic Ocean (some dust falls into the Atlantic), then at 35 degrees West longitude at the eastern coast of South America, 27.7 million tons (15%) of dust fall over the Amazon basin, 132 million tons of dust remain in the air, 43 million tons of dust are windblown and falls on the Caribbean Sea, past 75 degrees west longitude.[16]

CALIPSO uses a laser range finder to scan the Earth's atmosphere for the vertical distribution of dust and other aerosols. CALIPSO regularly tracks the Sahara-Amazon dust plume. CALIPSO has measured variations in the dust amounts transported— an 86 percent drop between the highest amount of dust transported in 2007 and the lowest in 2011.

A possibility causing the variation is the Sahel, a strip of semi-arid land on the southern border of the Sahara. When rain amounts in the Sahel are higher, the volume of dust is lower. The higher rainfall could make more vegetation grow in the Sahel, leaving less sand exposed to winds to blow away.[17]

Human activity

Based on archaeological evidence from an excavation at Caverna da Pedra Pintada, human inhabitants first settled in the Amazon region at least 11,200 years ago.[18] Subsequent development led to late-prehistoric settlements along the periphery of the forest by AD 1250, which induced alterations in the forest cover.[19]

Geoglyphs on deforested land in the Amazon rainforest, Acre.

For a long time, it was thought that the Amazon rainforest was only ever sparsely populated, as it was impossible to sustain a large population through agriculture given the poor soil. Archeologist Betty Meggers was a prominent proponent of this idea, as described in her book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise. She claimed that a population density of 0.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (0.52/sq mi) is the maximum that can be sustained in the rainforest through hunting, with agriculture needed to host a larger population.[20] However, recent anthropological findings have suggested that the region was actually densely populated. Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in AD 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that at Marajó, and inland dwellers.[21] By 1900 the population had fallen to 1 million and by the early 1980s it was less than 200,000.[21]

The first European to travel the length of the Amazon River was Francisco de Orellana in 1542.[22] The BBC's Unnatural Histories presents evidence that Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that a complex civilization was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. It is believed that the civilization was later devastated by the spread of diseases from Europe, such as smallpox.[23]

Since the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land dating between AD 1–1250, furthering claims about Pre-Columbian civilizations.[24][25] Ondemar Dias is accredited with first discovering the geoglyphs in 1977 and Alceu Ranzi with furthering their discovery after flying over Acre.[23][26] The BBC's Unnatural Histories presented evidence that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening and terra preta.[23] Terra preta is found over large areas in the Amazon forest; and is now widely accepted as a product of indigenous soil management. The development of this fertile soil allowed agriculture and silviculture in the previously hostile environment; meaning that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are probably the result of centuries of human management, rather than naturally occurring as has previously been supposed.[27] In the region of the Xingu tribe, remains of some of these large settlements in the middle of the Amazon forest were found in 2003 by Michael Heckenberger and colleagues of the University of Florida. Among those were evidence of roads, bridges and large plazas.[28]

Biodiversity

Deforestation

in the Amazon rainforest threatens many species of tree frogs, which

are very sensitive to environmental changes (pictured: giant leaf frog)

Scarlet macaw, which is indigenous to the American tropics.

Wet tropical forests are the most species-rich biome, and tropical forests in the Americas are consistently more species rich than the wet forests in Africa and Asia.[29] As the largest tract of tropical rainforest in the Americas, the Amazonian rainforests have unparalleled biodiversity. One in ten known species in the world lives in the Amazon rainforest.[30] This constitutes the largest collection of living plants and animal species in the world.

The region is home to about 2.5 million insect species,[31] tens of thousands of plants, and some 2,000 birds and mammals. To date, at least 40,000 plant species, 2,200 fishes,[32] 1,294 birds, 427 mammals, 428 amphibians, and 378 reptiles have been scientifically classified in the region.[33] One in five of all bird species are found in the Amazon rainforest, and one in five of the fish species live in Amazonian rivers and streams. Scientists have described between 96,660 and 128,843 invertebrate species in Brazil alone.[34]

The biodiversity of plant species is the highest on Earth with one 2001 study finding a quarter square kilometer (62 acres) of Ecuadorian rainforest supports more than 1,100 tree species.[35] A study in 1999 found one square kilometer (247 acres) of Amazon rainforest can contain about 90,790 tonnes of living plants. The average plant biomass is estimated at 356 ± 47 tonnes per hectare.[36] To date, an estimated 438,000 species of plants of economic and social interest have been registered in the region with many more remaining to be discovered or catalogued.[37] The total number of tree species in the region is estimated at 16,000.[2]

A giant, bundled liana in western Brazil

The green leaf area of plants and trees in the rainforest varies by about 25% as a result of seasonal changes. Leaves expand during the dry season when sunlight is at a maximum, then undergo abscission in the cloudy wet season. These changes provide a balance of carbon between photosynthesis and respiration.[38]

The rainforest contains several species that can pose a hazard. Among the largest predatory creatures are the black caiman, jaguar, cougar, and anaconda. In the river, electric eels can produce an electric shock that can stun or kill, while piranha are known to bite and injure humans.[39] Various species of poison dart frogs secrete lipophilic alkaloid toxins through their flesh. There are also numerous parasites and disease vectors. Vampire bats dwell in the rainforest and can spread the rabies virus.[40] Malaria, yellow fever and Dengue fever can also be contracted in the Amazon region.

- Bullet ants have an extremely painful sting

- Parrots at clay lick in Yasuni National Park, Ecuador

Deforestation

Deforestation in the Maranhão state of Brazil, 2016

Deforestation is the conversion of forested areas to non-forested areas. The main sources of deforestation in the Amazon are human settlement and development of the land.[41] Prior to the early 1960s, access to the forest's interior was highly restricted, and the forest remained basically intact.[42] Farms established during the 1960s were based on crop cultivation and the slash and burn method. However, the colonists were unable to manage their fields and the crops because of the loss of soil fertility and weed invasion.[43] The soils in the Amazon are productive for just a short period of time, so farmers are constantly moving to new areas and clearing more land.[43] These farming practices led to deforestation and caused extensive environmental damage.[44] Deforestation is considerable, and areas cleared of forest are visible to the naked eye from outer space.

In the 1970s construction began on the Trans-Amazonian highway. This highway represented a major threat to the Amazon rainforest.[45] Fortunately for the rainforest, the highway has not been completed, hereby reducing the environmental damage.

Between 1991 and 2000, the total area of forest lost in the Amazon rose from 415,000 to 587,000 square kilometres (160,000 to 227,000 sq mi), with most of the lost forest becoming pasture for cattle.[46] Seventy percent of formerly forested land in the Amazon, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, is used for livestock pasture.[47][48] Currently, Brazil is the second-largest global producer of soybeans after the United States. New research however, conducted by Leydimere Oliveira et al., has shown that the more rainforest is logged in the Amazon, the less precipitation reaches the area and so the lower the yield per hectare becomes. So despite the popular perception, there has been no economical advantage for Brazil from logging rainforest zones and converting these to pastoral fields.[49]

The needs of soy farmers have been used to justify many of the controversial transportation projects that are currently developing in the Amazon. The first two highways successfully opened up the rainforest and led to increased settlement and deforestation. The mean annual deforestation rate from 2000 to 2005 (22,392 km2 or 8,646 sq mi per year) was 18% higher than in the previous five years (19,018 km2 or 7,343 sq mi per year).[50] Although deforestation has declined significantly in the Brazilian Amazon between 2004 and 2014, there has been an increase to the present day.[51]

- Fires and deforestation in the state of Rondônia.

Conservation and climate change

Amazon rainforest

Environmentalists are concerned about loss of biodiversity that will result from destruction of the forest, and also about the release of the carbon contained within the vegetation, which could accelerate global warming. Amazonian evergreen forests account for about 10% of the world's terrestrial primary productivity and 10% of the carbon stores in ecosystems[52]—of the order of 1.1 × 1011 metric tonnes of carbon.[53] Amazonian forests are estimated to have accumulated 0.62 ± 0.37 tons of carbon per hectare per year between 1975 and 1996.[53]

One computer model of future climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions shows that the Amazon rainforest could become unsustainable under conditions of severely reduced rainfall and increased temperatures, leading to an almost complete loss of rainforest cover in the basin by 2100.[54][55] However, simulations of Amazon basin climate change across many different models are not consistent in their estimation of any rainfall response, ranging from weak increases to strong decreases.[56] The result indicates that the rainforest could be threatened though the 21st century by climate change in addition to deforestation.

In 1989, environmentalist C.M. Peters and two colleagues stated there is economic as well as biological incentive to protecting the rainforest. One hectare in the Peruvian Amazon has been calculated to have a value of $6820 if intact forest is sustainably harvested for fruits, latex, and timber; $1000 if clear-cut for commercial timber (not sustainably harvested); or $148 if used as cattle pasture.[57]

As indigenous territories continue to be destroyed by deforestation and ecocide, such as in the Peruvian Amazon[58] indigenous peoples' rainforest communities continue to disappear, while others, like the Urarina continue to struggle to fight for their cultural survival and the fate of their forested territories. Meanwhile, the relationship between non-human primates in the subsistence and symbolism of indigenous lowland South American peoples has gained increased attention, as have ethno-biology and community-based conservation efforts.

From 2002 to 2006, the conserved land in the Amazon rainforest has almost tripled and deforestation rates have dropped up to 60%. About 1,000,000 square kilometres (250,000,000 acres) have been put onto some sort of conservation, which adds up to a current amount of 1,730,000 square kilometres (430,000,000 acres).[59]

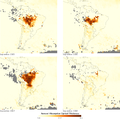

- Aerosols over the Amazon each September for four burning seasons (2005 through 2008). The aerosol scale (yellow to dark reddish-brown) indicates the relative amount of particles that absorb sunlight.

Remote sensing

This image reveals how the forest and the atmosphere interact to create a uniform layer of "popcorn-shaped" cumulus clouds.

The use of remotely sensed data is dramatically improving conservationists' knowledge of the Amazon basin. Given the objectivity and lowered costs of satellite-based land cover analysis, it appears likely that remote sensing technology will be an integral part of assessing the extent and damage of deforestation in the basin.[61] Furthermore, remote sensing is the best and perhaps only possible way to study the Amazon on a large scale.[62]

The use of remote sensing for the conservation of the Amazon is also being used by the indigenous tribes of the basin to protect their tribal lands from commercial interests. Using handheld GPS devices and programs like Google Earth, members of the Trio Tribe, who live in the rainforests of southern Suriname, map out their ancestral lands to help strengthen their territorial claims.[63] Currently, most tribes in the Amazon do not have clearly defined boundaries, making it easier for commercial ventures to target their territories.

To accurately map the Amazon's biomass and subsequent carbon related emissions, the classification of tree growth stages within different parts of the forest is crucial. In 2006 Tatiana Kuplich organized the trees of the Amazon into four categories: (1) mature forest, (2) regenerating forest [less than three years], (3) regenerating forest [between three and five years of regrowth], and (4) regenerating forest [eleven to eighteen years of continued development].[64] The researcher used a combination of Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and Thematic Mapper (TM) to accurately place the different portions of the Amazon into one of the four classifications.

Impact of early 21st-century Amazon droughts

In 2005, parts of the Amazon basin experienced the worst drought in one hundred years,[65] and there were indications that 2006 could have been a second successive year of drought.[66] A July 23, 2006 article in the UK newspaper The Independent reported Woods Hole Research Center results showing that the forest in its present form could survive only three years of drought.[67][68] Scientists at the Brazilian National Institute of Amazonian Research argue in the article that this drought response, coupled with the effects of deforestation on regional climate, are pushing the rainforest towards a "tipping point" where it would irreversibly start to die. It concludes that the forest is on the brink of being turned into savanna or desert, with catastrophic consequences for the world's climate.According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the combination of climate change and deforestation increases the drying effect of dead trees that fuels forest fires.[69]

In 2010 the Amazon rainforest experienced another severe drought, in some ways more extreme than the 2005 drought. The affected region was approximate 1,160,000 square miles (3,000,000 km2) of rainforest, compared to 734,000 square miles (1,900,000 km2) in 2005. The 2010 drought had three epicenters where vegetation died off, whereas in 2005 the drought was focused on the southwestern part. The findings were published in the journal Science. In a typical year the Amazon absorbs 1.5 gigatons of carbon dioxide; during 2005 instead 5 gigatons were released and in 2010 8 gigatons were released.[70][71] Additional severe droughts occurred in 2010, 2015, and 2016.