Tahiti is famous for black sand beaches

| |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 17°40′S 149°25′WCoordinates: 17°40′S 149°25′W |

| Archipelago | Society Islands |

| Major islands | Tahiti |

| Area | 1,044 km2 (403 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,241 m (7,352 ft) |

| Highest point | Mont Orohena |

| Administration | |

|

France

| |

| Overseas collectivity | French Polynesia |

| Largest settlement | Papeete (pop. 136,777 urban) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 189,517[1] (August 2017 census) |

| Pop. density | 181 /km2 (469 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Tahitians |

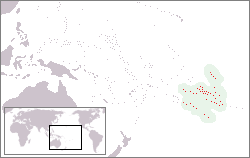

Location of French Polynesia

Tahiti (/təˈhiːti/; French pronunciation: [ta.iti]; previously also known as Otaheite (obsolete) is the largest island in the Windward group of French Polynesia. The island is located in the archipelago of the Society Islands in the central Southern Pacific Ocean, and is divided into two parts: the bigger, northwestern part, Tahiti Nui, and the smaller, southeastern part, Tahiti Iti. The island was formed from volcanic activity and is high and mountainous with surrounding coral reefs. The population is 189,517 inhabitants (2017 census), making it the most populous island of French Polynesia and accounting for 68.7% of its total population.

Tahiti is the economic, cultural and political centre of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity (sometimes referred to as an overseas country) of France. The capital of French Polynesia, Papeete, is located on the northwest coast of Tahiti. The only international airport in the region, Fa'a'ā International Airport, is on Tahiti near Papeete.

Tahiti was originally settled by Polynesians between 300 and 800 AD. They represent about 70% of the island's population, with the rest made up of Europeans, Chinese and those of mixed heritage.

The island was part of the Kingdom of Tahiti until its annexation by France in 1880, when it was proclaimed a colony of France, and the inhabitants became French citizens. French is the only official language, although the Tahitian language (Reo Tahiti) is widely spoken.

Geography

Tahiti-Mo'orea map.

Tahiti is the highest and largest island in French Polynesia lying close to Moorea island. It is located 4,400 kilometres (2,376 nautical miles) south of Hawaii, 7,900 km (4,266 nmi) from Chile, and 5,700 km (3,078 nmi) from Australia.[citation needed]

The island is 45 km (28 mi) across at its widest point and covers an area of 1,045 km2 (403 sq mi). The highest peak is Mont Orohena (Mou'a 'Orohena) (2,241 m (7,352 ft)). Mount Roonui, or Mount Ronui (Mou'a Rōnui), in the southeast rises to 1,332 m (4,370 ft). The island consists of two roughly round portions centred on volcanic mountains and connected by a short isthmus named after the small town of Taravao which is situated there.[citation needed]

Tahiti is an island located in the archipelago of the Society Islands. The archipelago is a part of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the French Republic situated in the central Southern Pacific Ocean.

The northwestern portion is known as Tahiti Nui ("big Tahiti"), while the much smaller southeastern portion is known as Tahiti Iti ("small Tahiti") or Tai'arapū. Tahiti Nui is heavily populated along the coast, especially around the capital, Papeete.[citation needed]

The interior of Tahiti Nui is almost entirely uninhabited.[2] Tahiti Iti has remained isolated, as its southeastern half (Te Pari) is accessible only to those travelling by boat or on foot. The rest of the island is encircled by a main road which cuts between the mountains and the sea.[citation needed]

A scenic and winding interior road climbs past dairy farms and citrus groves with panoramic views. Tahiti's landscape features lush rainforests and many rivers and waterfalls, including the Papenoo River on the north side, and the Fautaua Falls near Papeete.[3]

Geology

Diadem Mountain at Sunset, Tahiti, John LaFarge, c. 1891, Brooklyn Museum.

The Society archipelago is a hotspot volcanic chain consisting of ten islands and atolls. The chain is oriented along the N. 65° W. direction, parallel to the movement of the Pacific Plate. Due to the plate movement over the Society hotspot, the age of the islands decreases from 5 Ma at Maupiti to 0 Ma at Mehetia, where Mehetia is the inferred current location of the hotspot as evidenced by recent seismic activity. Maupiti, the oldest island in the chain, is a highly eroded shield volcano with at least 12 thin aa flows, which accumulated fairly rapidly between 4.79 and 4.05 Ma. Bora Bora is another highly eroded shield volcano consisting of basaltic lavas accumulated between 3.83 and 3.1 Ma. The lavas are intersected by post-shield dikes. Tahaa consists of shield-stage basalt with an age of 3.39 Ma, followed by additional eruptions 1.2 Ma later. Raiatea consists of shield-stage basalt followed by post-shield trachytic lava flows, all occurring from 2.75 to 2.29 Ma. Huahine consists of two coalesced basalt shield volcanoes, Huahine Nui and Huahine Iti, with several flows followed by post-shield trachyphonolitic lava domes from 3.08 to 2.06 Ma. Moorea consists of at least 16 flows of shield-stage basalt and post-shield lavas from 2.15 to 1.36 Ma. Tahiti consists of two basalt shield volcanoes, Tahiti Nui and Tahiti Iti, with an age range of 1.67 to 0.25 Ma.[4]

Climate

November to April is the wet season, the wettest month of which is January with 13.2 in (340 mm) of rain in Papeetē. August is the driest with 1.9 inches (48 millimetres).[citation needed]The average temperature ranges between 21 and 31 °C (70 and 88 °F), with little seasonal variation. The lowest and highest temperatures recorded in Papeete are 16 and 34 °C (61 and 93 °F), respectively.[5]

History

Prehistoric colonisation of Tahiti

The first Tahitians arrived from Western Polynesia in about 200 AD,[6] after a long migration from South East Asia or Indonesia, via the Fijian, Samoan and Tongan Archipelagos. This hypothesis of an emigration from Southeast Asia is supported by a number of linguistic, biological and archaeological proofs. For example, the languages of Fiji and Polynesia all belong to the same Oceanic sub-group, Fijian-Polynesian, which itself forms part of the great family of the Austronesian Languages.This emigration, across several hundred kilometres of ocean, was made possible by using outrigger canoes that were up to twenty or thirty meters long and could transport families as well as domestic animals. In 1769, for instance, James Cook mentions a great traditional ship (va'a) in Tahiti that was 33 m (108 ft) long, and could be propelled by sail or paddles.[7] In 2010, an expedition on a simple outrigger canoe with a sail retraced the route back from Tahiti to Asia.[8]

Civilisation before the arrival of the Europeans

Before the arrival of the Europeans the island was divided into different chiefdoms, very precise territories dominated by a single clan. These chiefdoms were linked to each other by allegiances based on the blood ties of their leaders and on their power in war. The most important clan on the island was the Teva,[9] whose territory extended from the peninsula in the south of Tahiti Nui. The Teva Clan was composed of the Teva i Uta (Teva of the Interior) and the Teva i Tai (Teva of the Sea), and was led by Amo and Purea.[10]

Captain Cook witnessed the ceremony of human sacrifice in Tahiti, c. 1773

A clan was composed of a chief (ari'i rahi), nobles (ari'i) and under-chiefs ( 'Īato'ai). The ari'i, considered descendants of the Polynesian gods, were full of mana (spiritual power). They traditionally wore belts of red feathers, symbols of their power. The chief of the clan did not have absolute power. Councils or general assemblies had to be called composed of the ari'i and the 'Īato'ai, especially in case of war.[9]

Each district or clan was organised around their marae, or stone temple. Anne Salmond quotes John Orsmond, an early missionary, as stating, "Marae were the sanctity and glory of the land, they were the pride of the people of these islands." This was especially true for the ancestral and national marae associated with the royal line. "It was the basis of royalty; It awakened the gods; It fixed the red feather girdle of the high chiefs."[11]:23,26–27

Followers of 'Oro were called ariori, and each district in Tahiti had an ariori lodge led by the avae parae, black leg. These leaders had legs tattooed from thigh to heel. The first 'Oro lodge was established around 1720 by Mahi, a representative of the high priest of Taputapuatea marae and Tamatoa I, the high chief of Ra'iatea. The first 'Oro marae was established at Tautira.[11]

Around 1750, war broke out between Atehuru and Papara, forcing Te'e'eva, the daughter of the Papara chief, to flee to Raiatea. She then married Tamatoa I's eldest son, Ari'ima'o, from which their son Mau'a was born. When Borabora warriors, led by Puni, invaded Raiatea in 1763, both Mau'a and the Taputapuatea priest Tupaia, were forced to flee to Tahiti, where the new Papara chief Amo and his wife Purea gave them refuge. This led to the building of the Mahaiatea marae at Papara. However, the marriage of Amo and Purea, and their status as black leg ariori, ended with the birth of their son Teri'irere. Tupaia then became Purea's lover. Tupaia would eventually sail with Captain Cook on the Endeavor, while Mau'a would sail with Lt. Gayangos on Aguila.[11]:35–38,60–61,85,134,208,277

First European visits

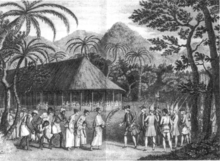

The meeting between Wallis and Oberea

Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, serving the Spanish Crown in an expedition to Terra Australis, was perhaps the first European to set eyes on the island of Tahiti. He sighted an inhabited island on 10 February 1606[12] which he called Sagitaria (or Sagittaria). However, whether the island that he saw was actually Tahiti or not has not been fully ascertained. It has been suggested that he actually saw the island of Rekareka to the south-east of Tahiti.[13] According to other authors the first European to arrive in Tahiti was Spanish explorer Juan Fernández in his expedition of 1576–1577.[14]

The first European to have visited Tahiti according to existing records was lieutenant Samuel Wallis, who was circumnavigating the globe in HMS Dolphin,[15] sighting the island on 18 June 1767,[16] and eventually harbouring in Matavai Bay. This bay was situated on the territory of the chiefdom of Pare-Arue, governed by Tu (Tu-nui-e-a'a-i-te-Atua) and his regent Tutaha, and the chiefdom of Ha'apape, governed by Amo and his wife "Oberea" (Purea). Wallis named the island King George's Island. The first contacts were difficult, since on the 24 and 26 June 1767,[17] Tahitian warriors in canoes showed aggression towards the British, hurling stones from their slings. In retaliation, the British sailors opened fire on the warriors in the canoes and on the hills. In reaction to this powerful counter-attack, the Tahitians laid down peace offerings for the British.[17] Following this episode, Samuel Wallis was able to establish cordial relations with the female chieftain "Oberea " (Purea) and remained on the island until 27 July 1767.[11]:45–84,104,135

Matavai Bay, painted by William Hodges, member of an expedition led by Cook

On 2 April 1768,[18] it was the turn of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, aboard Boudeuse and Etoile on the first French circumnavigation, to sight Tahiti. On 5 April, he anchored off Hitiaa O Te Ra, and was welcomed by its chief Reti. Bougainville was also visited by Tutaha. Bougainville only stayed about ten days on the island, which he called "Nouvelle-Cythère ", or "New Cythera (the island of Aphrodite)", because of the warm welcome he had received, the sweetness of the Tahitian customs, calling it a "sailor's Paradise." Ahutoru accompanied the French on the return voyage, becoming the first Tahitian to sail on a European vessel.[11]:93–109 The account Bougainville and Philibert Commerson gave of his port of call would contribute to the creation of the myth of a Polynesian paradise and nourished the theme of the noble savage, so dear to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which was very much in fashion.[11]:116–118 Between this date right until the end of the 18th century, the name of the island was spelled phonetically "Taïti". Beginning in the 19th century, the Tahitian orthography "Tahiti" became normal usage in French and English.[19]

In between the visits of Bougainville and Cook, in December 1768, a war of succession amongst the Tahiti's clans took place for who would assume the role of paramount chief. Tutaha's Pare-'Arue army allied with Vehiatua's Tai'arapu army, Pohuetea's Puna'auia army, To'ofa's Paea army, and Tepau-i-ahura'i (Tepau) of Fa'a'a, to defeat Amo and Purea in Papara. The warriors, women and children of Papara were massacred, while their houses, gardens, crops and livestock destroyed. Even the Mahaiatea marae was ransacked, while Amo, Purea, Tupaia and Teri'irere fled into the mountains. Vehiatua built a wall of skulls (Te-ahu-upo'o) at his Tai'arapu marae from his war trophies.[11]:134–140,144–145,196

In July 1768, Captain James Cook was commissioned by the Royal Society and on orders from the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to observe the transit of Venus across the sun, a phenomenon that would be visible from Tahiti on 3 June 1769.[20] He arrived in Tahiti's Matavai Bay, commanding HMS Endeavour on 12 April 1769.[21][11]:141 On 14 April, Cook met with Tutaha and Tepau.[11]:144 On 15 April, Cook picked the site for a fortified camp at Point Venus along with Banks, Parkinson, Daniel Solander, to protect Charles Green's observatory.[11]:147 The length of stay enabled them to undertake for the first time real ethnographic and scientific observations of the island. Assisted by the botanist Joseph Banks, and by the artist Sydney Parkinson, Cook gathered valuable information on the fauna and flora, as well as the native society, language and customs, including the proper name of the island, 'Otaheite'. On 28 April, Cook met Purea and Tupaia, and Tupaia befriended Banks following the transit. On 21 June, Amo visited Cook, and then on 25 June, Pohuetea visited, signifying another chief seeking to ally himself with the British.[11]:154–155,175,183–185

Cook and Banks circumnavigated the island from 26 June to 1 July. On the exploration, they met Ahio, chief of Ha'apaiano'o or Papenoo, Rita, chief of Hitia'a, Pahairro, chief of Pueu, Vehiatua, chief of Tautra, Matahiapo, chief of Teahupo'o, Tutea, chief of Vaira'o, and Moe, chief of Afa'Ahiti. In Papara, guided by Tupaia, they investigated the ruins of Mahaiatea marae, an impressive structure containing a stone pyramid or ahu, measuring 44 feet (13 m) high, 267 feet (81 m) long and 87 feet (27 m) wide. Cook and Endeavour departed Tahiti on 13 July 1769, taking Raiatean navigator Tupaia along for his geographic knowledge of the islands.[11]:149,186–202,205

Cook estimated the population to be 200,000 including all the nearby islands in the chain.[22][11]:308 This estimate was later lowered to 35,000 by anthropologist Douglas L. Oliver, the foremost modern authority on Tahiti, at the time of first European contact in 1767.[23]

In between the visits of Cook and Bonechea, the war of succession resumed amongst the Tahitian clans. This time Tutaha and his allies fought Vehiatua and his. Several famous battles were fought, including 'Taora ofa'i' (shower of stones) and 'Te-tamai-i-te-tai-'ute 'ute' (the battle of the red sea). Tutahua and Tepau were eventually killed in battle, while Vehiatua died of old age. Vehiatua's son, Paitu, became Vehiatua II, while Tu became paramount chief of the island, ari'i maro 'ura.[11]:242–244,273

The Viceroy of Peru, Manuel de Amat y Juniet, following the instructions of the Spanish Crown, organised an expedition to settle and colonise the island in 1772, largely to prevent other powers from gaining a base in the Pacific from which to attack the coast of Peru, but also to evangelise. He sent two expeditions under the command of navigator Domingo de Bonechea, the first in 1772, aboard Aguila. Four Tahitians, Pautu, Tipitipia, Heiao and Tetuanui, accompanied Bonechea on his return voyage to Peru in 1773.[11]:236–256,325

Cook returned to Tahiti between 15 August and 1 September 1773, greeted by the chiefs Tai and Puhi, besides the young ari'i Vehiatua II and his stepfather Ti'itorea. Cook anchored in Vaitepiha Bay before returning to Point Venus where he met Tu, the paramount chief. Cook picked up two passengers from Tahiti during this trip, Porea and Ma'i, with Hitihiti later replacing Porea when Cook stopped at Raiatea. Cook took Hitihiti to Tahiti on 22 April, during his return leg. Then, Cook departed Tahiti on 14 May 1774.[11]:263–279,284,290,301–312

Pautu and Tetuanui returned to Tahiti with Bonechea aboard Aguila on 14 November 1774, Tipitipia and Heiao having passed away in the interim. Bonechea died on 26 January 1775 in Tahiti, and was buried near the Spanish mission at Tautira Bay. Lt. Tomas Gayangos took over command. Gayangos set sail for Peru on 27 Jan, leaving the two friars, Father Geronimo Clota and Father Narciso Gonzalez, and Maximo Rodriguez and Francisco Perez, in charge of the Spanish mission. However, the Spanish mission on Tahiti was abandoned on 12 November 1775, after Aguila's third voyage to Tahiti, when the Fathers begged its commander, Don Cayetano de Langara, to take them back to Lima.[24] Some maps still bear the name Isla de Amat for Tahiti, named after Viceroy Amat who ordered the expedition.[25] A most notable result of these voyages was the journal by a marine in the Spanish Navy named Maximo Rodriguez, which contains valuable information about the Tahitians of the 18th century, augmented with the accounts by the Chilean Don Jose de Andia y Varela.[11]:321,323,340,351–357,361,381–383

During his final visit, Cook returned Ma'i to Tahiti on 12 August 1777, after Ma'i's long visit in England. Cook also brought two Maori from Queen Charlotte Sound, Te Weherua and Koa. Cook first harboured in Vaitepiha Bay, where he visited Vehiatua II's funeral bier and the prefabricated Spanish mission house. Cook also met Vehiatua III, and inscribed on the back of the Spanish cross, Georgius tertius Rex Annis 1767, 69, 73, 74 & 77, as a counterpoint to Christus Vincit Carolus III imperat 1774 on the front. On 23 August, Cook sailed for Matavai Bay, where he met Tu, his father Teu, his mother Tetupaia, his brothers Ari'ipaea and Vaetua, and his sisters Ari'ipaea-vahine, Tetua-te-ahama'i, and Auo. Cook also observed a human sacrifice, ta'ata tapu, at the 'Utu-'ai-mahurau marae, and 49 skulls from previous victims.[11]:405,419–435

On 29 September 1777, Cook sailed for Papeto'ai Bay on Mo'orea. Cook met Mahine in an act of friendship on 3 October, though he was an enemy of Tu. When a goat kid was stolen on 6 October, Cook, in a rage, ordered the burning of houses and canoes until it was returned. Cook sailed for Huahine on 11 October, Raiatea on 2 November, and Borabora on 7 December.[11]:440–444,447

British influence and the rise of the Pōmare

Mutineers of the Bounty

William Bligh overseeing the transplantation of breadfruit trees from Tahiti

On 26 October 1788, HMS Bounty, under the command of Captain William Bligh, landed in Tahiti with the mission of carrying Tahitian breadfruit trees (Tahitian: 'uru) to the Caribbean. Sir Joseph Banks, the botanist from James Cook's first expedition, had concluded that this plant would be ideal to feed the African slaves working in the Caribbean plantations at very little cost. The crew remained in Tahiti for about five months, the time needed to transplant the seedlings of the trees. Three weeks after leaving Tahiti, on 28 April 1789, the crew mutinied on the initiative of Fletcher Christian. The mutineers seized the ship and set the captain and most of those members of the crew who remained loyal to him adrift in a ship's boat. A group of mutineers then went back to settle in Tahiti.

Although various explorers had refused to get involved in tribal conflicts, the mutineers from Bounty offered their services as mercenaries and furnished arms to the family which became the Pōmare Dynasty. The chief Tū knew how to use their presence in the harbours favoured by sailors to his advantage. As a result of his alliance with the mutineers, he succeeded in considerably increasing his supremacy over the island of Tahiti.

In about 1790, the ambitious chief Tū took the title of king and gave himself the name Pōmare. Captain Bligh explains that this name was a homage to his eldest daughter Teriinavahoroa, who had died of tuberculosis, "an illness that made her cough (mare) a lot, especially at night (pō)". Thus he became Pōmare I, founding the Pōmare Dynasty and his lineage would be the first to unify Tahiti from 1788 to 1791. He and his descendants founded and expanded Tahitian influence to all of the lands that now constitute modern French Polynesia.

In 1791, HMS Pandora under Captain Edward Edwards called at Tahiti and took custody of fourteen of the mutineers. Four were drowned in the sinking of Pandora on her homeward voyage, three were hanged, four were acquitted, and three were pardoned.

Landings of the whalers

In the 1790s, whalers began landing at Tahiti during their fishing expeditions in the southern hemisphere. The arrival of these whalers, who were subsequently joined by merchants coming from the penal colonies in Australia, marked the first major overturning of traditional Tahitian society. The crews introduced alcohol, arms and illnesses into the island, and encouraged prostitution, which brought with it venereal disease. These first exchanges with westerners had catastrophic consequences for the Tahitian population, which shrank rapidly, ravaged by diseases. So many Tahitians were killed by disease in fact that by 1797, the population was only 16,000. Later it was to drop as low as 6,000.[26]Arrival of the missionaries

On 5 March 1797, representatives of the London Missionary Society landed at Matavai Bay (Mahina) on board Duff, with the intention of converting the pagan native populations to Christianity. The arrival of these missionaries marked a new turning point for the island of Tahiti, having a lasting impact on the local culture.The first years proved hard work for the missionaries, despite their association with the Pōmare, the importance of whom they were aware of thanks to the reports of earlier sailors. In 1803, upon the death of Pōmare I, his son Vaira'atoa succeeded him and took the title of Pomare II. He allied himself more and more with the missionaries, and from 1803 they taught him reading and the Gospels. Furthermore, the missionaries encouraged his wish to conquer his opponents, so that they would only have to deal with a single political contact, enabling them to develop Christianity in a unified country.[9] The conversion of Pōmare II to Protestantism in 1812 marks moreover the point when Protestantism truly took off on the island.

In about 1810, Pōmare II married Teremo'emo'e daughter of the chief of Raiatea, to ally himself with the chiefdoms of the Leeward Islands. On 12 November 1815, thanks to these alliances, Pōmare II won a decisive battle at Fe'i Pī (Punaauia), notably against Opuhara,[27] the chief of the powerful clan of Teva.[10] This victory allowed Pōmare II to be styled Ari'i Rahi, or the king of Tahiti. It was the first time that Tahiti had been united under the control of a single family. It was the end of Tahitian feudalism and the military aristocracy, which were replaced by an absolute monarchy. At the same time, Protestantism quickly spread, thanks to the support of Pōmare II, and replaced the traditional beliefs. In 1816 the London Missionary Society sent John Williams as a missionary and teacher, and starting in 1817, the Gospels were translated into Tahitian (Reo Maohi) and taught in the religious schools. In 1818, the minister William Pascoe Crook founded the city of Papeete, which became the capital of the island.

Tahitians in missionary robes

In 1819, Pōmare II, encouraged by the missionaries, introduced the first Tahitian legal code, known under the name of the Pōmare Legal Code,[9] which consists of nineteen laws. The missionaries and Pōmare II thus imposed a ban on nudity (obliging them to wear clothes covering their whole body), banned dances and chants, described as immodest, tattoos and costumes made of flowers.

In the 1820s, the entire population of Tahiti converted to Protestantism. Duperrey, who berthed in Tahiti in May 1823, attests to the change in Tahitian society in a letter dated 15 May 1823: "The missionaries of the Royal Society of London have totally changed the morals and customs of the inhabitants. Idolatry no longer exists among them, and they generally profess the Christian religion. The women no longer come aboard the vessel, and even when we meet them on land they are extremely reserved. (...) The bloody wars that these people used to carry out and human sacrifices have no longer taken place since 1816."[28]

When, on 7 December 1821, Pōmare II died, his son Pōmare III was only eighteen months old. His uncle and the religious people therefore supported the regency, until 2 May 1824, the date on which the missionaries conducted his coronation, a ceremony unprecedented in Tahiti. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Pōmare, local chiefs won back some of their power and took the hereditary title of Tavana (from the English word 'governor'). The missionaries also took advantage of the situation to change the way in which powers were arranged, and to make the Tahitian monarchy closer to the English model of a constitutional monarchy. They therefore created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly, which first sat on 23 February 1824.

In 1827, the young Pōmare III suddenly died, and it was his half-sister, 'Aimata, aged thirteen, who took the title of Pōmare IV. The Birmingham born missionary George Pritchard, who was the acting British consul, became her main adviser and tried to interest her in the affairs of the kingdom. But the authority of the Queen, who was certainly less charismatic than her father, was challenged by the chiefs, who had won back an important part of their prerogatives since the death of Pōmare II. The power of the Pōmare had become more symbolic than real, time and time again Queen Pōmare, Protestant and anglophile, sought in vain the protection of England.[9]

Dupetit Thouars taking over Tahiti on 9 September 1842

In November 1835 Charles Darwin visited Tahiti aboard HMS Beagle on her circumnavigation, captained by Robert FitzRoy. He was impressed by what he perceived to be the positive influence the missionaries had had on the sobriety and moral character of the population. Darwin praised the scenery, but was not flattering towards Tahiti's Queen Pōmare IV. Captain Fitzroy negotiated payment of compensation for an attack on an English ship by Tahitians, which had taken place in 1833.[29]

Queen Pōmare IV, 1813–1877

In Sept. 1839, the island was visited by the United States Exploring Expedition.[30] One of its members, Alfred Thomas Agate, produced a number of sketches of Tahitian life, some of which were later published in the United States.

French protectorate and the end of the Pōmare kingdom

Queen Pomare and her family on the verandah of Mr. Pritchard's house, during the French Invasion of Tahiti, from the Missionary Repository for Youth and Sunday School Missionary Magazine, 1847[31]

In 1836, the Queen's advisor Pritchard had two French Catholic priests expelled, François Caret and Honoré Laval. As a result, in 1838 France sent Admiral Abel Aubert Dupetit-Thouars to get reparation. Once his mission had been completed, Admiral Du Petit-Thouars sailed towards the Marquesas Islands, which he annexed in 1842. Also in 1842, a European crisis involving Morocco escalated between France and Great Britain, souring their relations. In August 1842, Admiral Du Petit-Thouars returned and landed in Tahiti. He then made friends with Tahitian chiefs who were hostile to the Pōmare family and favourable to a French protectorate. He had them sign a request for protection in the absence of their Queen, before then approaching her and obliging her to ratify the terms of the treaty of protectorate. The treaty had not even been ratified by France itself when Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout was named royal commissaire alongside Queen Pōmare.

Within the framework of this treaty, France recognised the sovereignty of the Tahitian state. The Queen was responsible for internal affairs, while France would deal with foreign relations and assure the defence of Tahiti, as well as maintain order on the island. Once the treaty had been signed there began a struggle for influence between the English Protestants and the Catholic representatives of France. During the first years of the Protectorate, the Protestants managed to retain a considerable hold over Tahitian society, thanks to their knowledge of the country and its language. George Pritchard had been away at the time. He returned however to work towards indoctrinating the locals against the Roman Catholic French.

Tahitian War of independence (1844–47)

In 1843, the Queen's Protestant advisor, Pritchard, persuaded her to display the Tahitian flag in place of the flag of the Protectorate.[32] By way of reprisal, Admiral Dupetit-Thouars announced the annexation of the Kingdom of Pōmare on 6 November 1843 and set up the governor Armand Joseph Bruat there as the chief of the new colony. He threw Pritchard into prison, and later sent him back to Britain. The annexation caused the Queen to be exiled to the Leeward Islands, and after a period of troubles, a real Franco-Tahitian war began in March 1844. News of Tahiti reached Europe in early 1844. The French statesman François Guizot, supported by King Louis-Philippe of France, had denounced annexation of the island.The war ended in December 1846 in favour of the French. The Queen returned from exile in 1847 and agreed to sign a new covenant, considerably reducing her powers, while increasing those of the commissaire. The French nevertheless still reigned over the Kingdom of Tahiti as masters. In 1863, they put an end to the British influence and replaced the British Protestant Missions with the Société des missions évangéliques de Paris (Society of Evangelical Missions of Paris).

During the same period about a thousand Chinese, mainly Cantonese, were recruited at the request of a plantation owner in Tahiti, William Stewart, to work on the great cotton plantation at Atimaono. When the enterprise resulted in bankruptcy in 1873, a few Chinese workers returned to their country, but a large number stayed in Tahiti and mixed with the population.

In 1866 the district councils were formed, elected, which were given the powers of the traditional hereditary chiefs. In the context of the republican assimilation, these councils tried their best to protect the traditional way of life of the local people, which was threatened by European influence.[citation needed]

Tahitian children, c. 1906

In 1877, Queen Pōmare died after ruling for fifty years. Her son, Pōmare V, then succeeded her on the throne. The new king seemed little concerned with the affairs of the kingdom, and when in 1880 the governor Henri Isidore Chessé, supported by the Tahitian chiefs, pushed him to abdicate in favour of France, he accepted. On 29 June 1880, he ceded Tahiti to France along with the islands that were its dependencies. He was given the titular position of Officer of the Orders of the Legion of Honour and Agricultural Merit of France. Having become a colony, Tahiti thus lost all sovereignty. Tahiti was nevertheless a special colony, since all the subjects of the Kingdom of Pōmare would be given French citizenship.[33] On 14 July 1881, among cries of "Vive la République!" the crowds celebrated the fact that Polynesia now belonged to France; this was the first celebration of the Tiurai (national and popular festival). In 1890, Papeete became a commune of the Republic of France.

The French painter Paul Gauguin lived on Tahiti in the 1890s and painted many Tahitian subjects. Papeari has a small Gauguin museum.

In 1891 Matthew Turner, an American shipbuilder from San Francisco who had been seeking a fast passage between the city and Tahiti, built Papeete, a two-masted schooner that made the trip in seventeen days.[citation needed]

Twentieth century to present

In 1903, the Établissements Français d'Océanie (French Establishments in Oceania) were created, which collected together Tahiti, the other Society Islands, the Austral Islands, the Marquesas Islands and the Tuamotu Archipelago.

A one-franc World War II banknote (1943), printed in Papeete, depicting the outline of Tahiti on reverse

During the First World War, the Papeete region of the island was attacked by two German warships. A French gunboat as well as a captured German freighter were sunk in the harbour and the two German armoured cruisers bombarded the colony. Between 1966 and 1996 the French Government conducted 193 nuclear bomb tests above and below the atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa. The last test was conducted on 27 January 1996.[34]

In 1946, Tahiti and the whole of French Polynesia became an overseas territory (Territoire d'outre-mer). Tahitians were granted French citizenship, a right that had been campaigned for by nationalist leader Pouvanaa a Oopa for many years.[35] In 2003, French Polynesia's status was changed to that of an overseas collectivity (Collectivité d'outre-mer) and in 2004 it was declared an overseas country (pays d'outre-mer or POM).

In 2009, Tauatomo Mairau claimed the Tahitian throne, and attempted to re-assert the status of the monarchy in court.

On 2 April 2018, the doomed Chinese space station Tiangong-1 that de-orbited and fell to Earth narrowly missed hitting Tahiti as it disintegrated.

Politics

Flag of Tahiti

Political map of Oceania, showing EEZ borders

Tahitians are French citizens with complete civil and political rights. French is the official language but Tahitian and French are both in use. However, there was a time during the 1960s and 1970s when children were forbidden to speak Tahitian in schools. Tahitian is now taught in schools; it is sometimes even a requirement for employment.

Tahiti is part of French Polynesia. French Polynesia is a semi-autonomous territory of France with its own assembly, president, budget and laws. France's influence is limited to subsidies, education and security.

During a press conference on 26 June 2006 during the second France-Oceania Summit, French President Jacques Chirac said he did not think the majority of Tahitians wanted independence. He would keep an open door to a possible referendum in the future.

Elections for the Assembly of French Polynesia, the Territorial Assembly of French Polynesia, were held on 23 May 2004.

In a surprise result, Oscar Temaru's pro-independence progressive coalition, Union for Democracy, formed a government with a one-seat majority in the 57-seat parliament, defeating the conservative party, Tahoera'a Huiraatira, led by Gaston Flosse. On 8 October 2004, Flosse succeeded in passing a censure motion against the government, provoking a crisis. A controversy is whether the national government of France should use its power to call for new elections in a local government in case of a political crisis.

Demographics

The indigenous Tahitians are of Polynesian ancestry comprising 70% of the population alongside Europeans, East Asians (mostly Chinese) and people of mixed heritage sometimes referred to as Demis. They make up the largest population in French Polynesia. Most people from metropolitan France live in Papeete and its suburbs, notably Punaauia where they make up almost 20% of the population.[citation needed]

Administrative divisions

The island consists of 12 communes, which, along with Moorea-Maiao, make up the Windward Islands administrative subdivision.The capital is Pape'ete and the largest commune by population is Fa'a'ā while Taiarapu-Est has the largest area.

Communes of Tahiti

The following is a list of communes and their subdivisions sorted alphabetically:[44]| Commune | Population | Area | Density | Subdivisions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arue | 9,494 | 21.45 km2 (8.28 sq mi) | 443/km2 (1,150/sq mi) | Tetiaroa, an atoll north of Arue belongs to the commune. | |

| Fa'a'ā | 29,781 | 34.2 km2 (13.2 sq mi) | 871/km2 (2,260/sq mi) | Largest commune (by population) in Tahiti and French Polynesia. | |

| Hitiaa O Te Ra | 8,691 | 218.2 km2 (84.2 sq mi) | 40/km2 (100/sq mi) | Hitiaa, Mahaena, Papenoo, Tiarei | The administrative centre of the commune is the settlement of Hitiaa. |

| Mahina | 14,356 | 51.6 km2 (19.9 sq mi) | 278/km2 (720/sq mi) | Close to the Papenoo River. | |

| Paea | 12,084 | 64.5 km2 (24.9 sq mi) | 187/km2 (480/sq mi) | ||

| Papara | 10,634 | 92.5 km2 (35.7 sq mi) | 115/km2 (300/sq mi) | ||

| Pape'ete | 26,050 | 17.4 km2 (6.7 sq mi) | 1,497/km2 (3,880/sq mi) | Capital of French Polynesia and 2nd largest city. | |

| Pirae | 14,551 | 35.4 km2 (13.7 sq mi) | 411/km2 (1,060/sq mi) | Located between Papeete and Arue. | |

| Punaauia | 25,399 | 75.9 km2 (29.3 sq mi) | 335/km2 (870/sq mi) | French painter Paul Gauguin lived in Punaauia in the 1890s. Punaauia is the 3rd largest city in French Polynesia. | |

| Taiarapu-Est | 11,538 | 218.3 km2 (84.3 sq mi) | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) | Afaahiti, Faaone, Pueu, Tautira | An offshore island called Mehetia belongs to the commune. |

| Taiarapu-Ouest | 7,007 | 104.3 km2 (40.3 sq mi) | 67/km2 (170/sq mi) | Teahupo'o, Taohotu, Vairao | Extends over half of the peninsula of Tahiti Iti. |

| Teva I Uta | 8,591 | 119.5 km2 (46.1 sq mi) | 72/km2 (190/sq mi) | Mataiea, Papeari | The administrative centre of the commune is the settlement of Mataiea. |

Economy

Tourism is a significant industry.

Southern suburbs of Papeete (commune of Punaauia).

In July, the Heivā festival in Papeete celebrates Polynesian culture and the commemoration of the storming of the Bastille in Paris. After the establishment of the CEP (Centre d'Experimentation du Pacifique) in 1963, the standard of living in French Polynesia increased considerably and many Polynesians abandoned traditional activities and emigrated to the urban centre of Pape'ete. Even though the standard of living is elevated (due mainly to French foreign direct investment), the economy is reliant on imports. At the cessation of CEP activities, France signed the Progress Pact with Tahiti to compensate the loss of financial resources and assist in education and tourism with an investment of about US$150 million a year from the beginning of 2006.

The main trading partners are Metropolitan France for about 40% of imports and about 25% of exports, the other main trading partners are the US, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

Tahitian pearl (Black pearl) farming is also a substantial source of revenues, most of the pearls being exported to Japan, Europe and the US. Tahiti also exports vanilla, fruits, flowers, monoi, fish, copra oil, and noni. Tahiti is also home to a single winery, whose vineyards are located on the Rangiroa atoll.[45]

Unemployment affects about 13% of the active population, especially women and unqualified young people.

Tahiti's currency, the French Pacific Franc (CFP, also known as XPF), is pegged to the Euro at 1 CFP = EUR .0084 (1 EUR = 119.05 CFP, approx. 113 CFP to the US Dollar in March 2017). Hotels and financial institutions offer exchange services.

Sales tax in Tahiti is called Taxe sur la Valeur Ajoutée (TVA or value added tax (V.A.T.) in English). V.A.T. 2009 on tourist services is 10% and V.A.T. 2009 on hotels, small boarding houses, food and beverages is 6%. V.A.T. on the purchase of goods and products is 16%.

Energy and electricity

French Polynesia imports its petroleum and has no local refinery or production. Daily consumption of imported oil products was 7,430 barrels, according to the US Energy Information Administration.[46]Culture

Tahitian woman in festive costume c. 1906

Tahitian cultures included an oral tradition that involved the mythology of gods, such as 'Oro and beliefs, as well as ancient traditions such as tattooing and navigation. The annual Heivā Festival in July is a celebration of traditional culture, dance, music and sports including a long distance race between the islands of French Polynesia, in modern outrigger canoes (va'a).

The Paul Gauguin Museum is dedicated to the life and works of French artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) who painted famous works such as Two Tahitian Women, Tahitian Women on the Beach and Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?.

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles (Museum of Tahiti and the Island) is in Punaauia. It is an ethnographic museum that was founded in 1974 to conserve and restore Polynesian artefacts and cultural practices.

The Robert Wan Pearl Museum is the world's only museum dedicated to pearls. The Papeete Market sells local arts and crafts.

Dance

Tahitians wearing the pareo wrap-around garment and practising a 'upa'upa dance

One of the most widely recognised images of the islands is the world-famous Tahitian dance. The 'ote'a (sometimes written as otea) is a traditional dance from Tahiti, where the dancers, standing in several rows, execute figures. This dance, easily recognised by its fast hip-shaking and grass skirts, is often confused with the Hawaiian hula, a generally slower more graceful dance which focuses more on the hands and storytelling than the hips.

The ʻōteʻa is one of the few dances which existed in pre-European times as a male dance. On the other hand, the hura (Tahitian vernacular for hula), a dance for women, has disappeared, and the couple's dance 'upa'upa is likewise gone but may have re-emerged as the tamure. Nowadays, the ʻōteʻa can be danced by men (ʻōteʻa tāne), by women (ʻōteʻa vahine), or by both genders (ʻōteʻa ʻāmui = united ʻō.). The dance is with music only, drums, but no singing. The drum can be one of the types of the tōʻere, a laying log of wood with a longitudinal slit, which is struck by one or two sticks. Or it can be the pahu, the ancient Tahitian standing drum covered with a shark skin and struck by the hands or with sticks. The rhythm from the tōʻere is fast, from the pahu it is slower. A smaller drum, the faʻatete, can be used.

The dancers make gestures, re-enacting daily occupations of life. For the men the themes can be chosen from warfare or sailing, and then they may use spears or paddles.

For women the themes are closer to home or from nature: combing their hair or the flight of a butterfly, for example. More elaborate themes can be chosen, for example, one where the dancers end up in a map of Tahiti, highlighting important places. In a proper ʻōteʻa the story of the theme should pervade the whole dance.

The group dance called 'Aparima is often performed with the dancers dressed in pareo and maro. There are two types of ʻaparima: the ʻaparima hīmene (sung handdance) and the ʻaparima vāvā (silent handdance), the latter being performed with music only and no singing.

Newer dances include the hivinau and the pa'o'a.

Death

W. Woolett engraving after William Hodges of a toupapow, or funeral bier, and Chief Mourner, from Cook's 2nd voyage to Tahiti

Tahitian Parae, or Chief Mourner costume, on display in the Bishop Museum

The Tahitians believed in the afterlife, a paradise called Rohutu-no'ano'a. When a Tahitian died, the barkcloth wrapped corpse was placed on a funeral bier, fare tupapa 'u, which was a raised canoe awning on posts surrounded by bamboo. Food for the gods was placed nearby to prevent them from eating the body, which would condemn the spirit to the underworld. Mourners would slash themselves with shark's teeth and the blood smeared on barkcloth placed nearby. Most importantly, the Chief Mourner, donned the parae, an elaborate costume composed of an iridescent mask made of four polished pearl shell discs. One disk was black signifying Po, the spirit world, while one was white, signifying Ao, the world of people. A crown of red feathers signified 'Oro. A curved wooden board, pautu, below the mask contained five polished pearl shells, which signified Hina, the moon goddess. Hanging below were more shells in rows, ahu-parau, signifying the Pleiades, considered to be the eyes of former chiefs. Finally, a ceremonial garment, tiputa, covered the body and was decorated with an apron of polished coconut shells, ahu-'aipu.[11]:151-152,177-179,308

Sport

The Tahitian national sport is Va'a. In English, this paddle sport is also known as outrigger canoe. The Tahitians consistently achieve record-breaking and top times as world champion in this sport.Major sports in Tahiti include rugby union and association football and the island has fielded a national basketball team, which is a member of FIBA Oceania.

Another sport is surfing, with famous surfers such as Malik Joyeux and Michel Bourez. Teahupo'o is one of the deadliest surf breaks in the world.

Rugby union in Tahiti is governed by the Fédération Tahitienne de Rugby de Polynésie Française which was formed in 1989. The Tahiti national rugby union team has been active since 1971 but have only played 12 games since then.

Football in Tahiti is administered by the Fédération Tahitienne de Football and was founded in 1938. The Tahiti Division Fédérale is the top division on the island and the Tahiti Championnat Enterprise is the second tier. Some of the major clubs are AS Manu-Ura, who play in Stade Hamuta, AS Pirae, who play in the Stade Pater Te Hono Nui and AS Tefana, who play in the Stade Louis Ganivet. Lesser clubs include Matavai. In 2012, the national team won the OFC Nations Cup qualifying for the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup in Brazil and becoming the first team other than Australia or New Zealand to win it.

The Tahiti Cup is the islands' premier football knockout tournament and has been played for since 1938. The winner of the Tahiti Cup goes on to play the winner of the Tahiti Division Fédérale in the Tahiti Coupe des Champions.

In 2010, Tahiti was chosen as the host of the 2013 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup, which was held in September 2013.

In 2011, Tahiti was accepted into as a member of the Asia-Pacific Rugby League Federation. Tahiti join as new members along with India, Philippines, Tokelau and American Samoa in a meeting of the federation in Auckland over 5–6 December. This is a sign of the growing popularity of Rugby league in the Pacific islands.[citation needed]

Tahiti has also been represented at the World Championship of Pétanque. They are the pre-eminent country in the Oceania region for Pétanque, undoubtably due to their strong connections to France.

Education

Tahiti is home to the University of French Polynesia (Université de la Polynésie Française). It is a growing university, with 3,200 students and 62 researchers. Many courses are available such as law, commerce, science, and literature. There is also the Collège La Mennais located in Papeete.Transport

Air

Tahitian coast

Faa'a International Airport is located 5 km (3.1 mi) from Papeete in the commune of Faaa and is the only international airport in French Polynesia. Because of limited level terrain, rather than levelling large stretches of sloping agricultural land, the airport is built primarily on reclaimed land on the coral reef just off-shore.

International destinations such as Auckland, Hanga Roa, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Paris, Santiago de Chile, Sydney and Tokyo are served by Air France, Air New Zealand, Air Tahiti Nui French Polynesia's flag carrier, Hawaiian Airlines and LATAM Airlines.

Flights within French Polynesia and to New Caledonia are available from Aircalin and Air Tahiti; Air Tahiti has their headquarters at the airport.

Ferry

Two Tahitian girls with a hibiscus flower

The Mo'orea Ferry operates from Papeete and takes about 45 minutes to travel to Moorea. Other ferries are the Aremiti 5 and the Aremiti 7 and these two ferries sail to Moorea in about half an hour. There are also several ferries that transport people and goods throughout the islands. The Bora Bora cruiseline sails to Bora Bora about once a week. The main hub for these ferries is the Papeete Wharf.