Tibetan Gelug monk and sand mandala

Tibetan Buddhism has exerted a particularly strong influence on Tibetan culture since its introduction in the seventh century. Buddhist missionaries who came mainly from India, Nepal and China introduced arts and customs from India and China. Art, literature, and music all contain elements of the prevailing Buddhist beliefs, and Buddhism itself has adopted a unique form in Tibet, influenced by the Bön tradition and other local beliefs.

Several works on astronomy, astrology and medicine were translated from Sanskrit and Classical Chinese. The general appliances of civilization have come from China, among many things and skill imported were the making of butter, cheese, barley-beer, pottery, watermills and the national beverage, butter tea.

Tibet's specific geographic and climatic conditions have encouraged reliance on pastoralism, as well as the development of a different cuisine from surrounding regions, which fits the needs of the human body in these high altitudes.

Tibetan language

The Tibetan language is spoken in a variety of dialects in all parts of the Tibetan-inhabited area which covers 1/2 Million square miles. Some of these dialects are tonal like the Chinese language, while others remain non-tonal. Historically Tibet was divided into three cultural provinces called U-Tsang, Kham and Amdo. Each one of these three provinces has developed its own distinct dialect of Tibetan. Most widely spoken is the Lhasa dialect, also called Standard Tibetan, which is spoken in Central Tibet and also in Exile by most Tibetans. In Kham the Khams Tibetan dialect is spoken and in Amdo the Amdo Tibetan dialect. The Tibetan dialects are subject to the Tibetic languages which are part of the Tibeto-Burman languages. Modern Tibetan derives from Classical Tibetan, which is the written norm, and from Old Tibetan. The official language of Bhutan, Dzongkha, is also closely related to Tibetan.Visual arts

Tibetan art is deeply religious in nature, a form of religious art. It spreads over a wide range of paintings, frescos, statues, ritual objects, coins, ornaments and furniture.

Tibetan art is deeply religious sacred art. Tagong Monastery, 2009, using butter lamps

Mahayana Buddhist influence

As Mahayana Buddhism emerged as a separate school in the fourth century BCE. It emphasized the role of bodhisattvas, compassionate beings who forgo their personal escape to nirvana in order to assist others. From an early time various bodhisattvas were also subjects of statuary art. Tibetan Buddhism, as an offspring of Mahayana Buddhism, inherited this tradition.A common bodhisattva depicted in Tibetan art is the Avalokiteśvara, often portrayed as a four or a thousand-armed saint with an eye in the middle of each hand, representing the all-seeing compassionate one who hears our requests. The Dalai Lama is believed to be his reincarnation.

Tantric influence

Most of the typical Tibetan Buddhist art can be seen as part of the practice of tantra. A surprising aspect of Tantric Buddhism is the common representation of fierce deities, often depicted with angry faces, circles of flame, or with the skulls of the dead. These images represent Dharmapalas "Protectors"; their fearsome bearing belies their true compassionate nature. Their wrath represents their dedication to the protection of the dharma as well as to the protection of the specific tantric practices to prevent corruption or disruption of the practice.Bön influence

The indigenous shamanistic religion of the Himalayas is known as Bön. Bön contributes a pantheon of local tutelary deities to Tibetan art. In Tibetan temples, known as lhakhang, statues of Gautama Buddha or Padmasambhava are often paired with statues of the tutelary deity of the district who often appears angry or dark. These gods once inflicted harm and sickness on the local citizens but after the arrival of Padmasambhava, these negative forces have been subdued and now must serve Buddhism.Rugs

The Tibetan uses rugs for almost any domestic use from flooring to wall hanging to horse saddles.

Tibetan rug making is an ancient art and craft in the tradition of Tibetan people. These rugs are primarily made from Tibetan highland sheep's virgin wool. The Tibetan uses rugs for almost any domestic use from flooring to wall hanging to horse saddles. Traditionally the best rugs are from Gyantse, a city which is known for its rugs.

The process of making Tibetan rugs is unique in the sense that almost everything is done by hand. But with the introduction of modern technology, a few aspects of the rug making processes have been taken over by machine primarily because of cost, the disappearance of knowledge etc. Moreover, some new finishing touches are also made possible by machine.

Tibetan rugs are big business in not only Tibet, but also Nepal, where Tibetan immigrants brought with them their knowledge of rug making. Currently in Nepal the rug business is one of the largest industries in the country and there are many rug exporters.

Painting

Thangkas, a syncrestistic art of Chinese hanging scrolls with Nepalese and Kashmiri painting, first survive from the eleventh century. Rectangular and intricately painted on cotton or linen, they are usually traditional compositions depicting deities, famous monks, and other religious, astrological, and theological subjects, and sometimes mandalas. To ensure that the image will not fade, the painting is framed in colorful silk brocades, and stored rolled up. The word thangka means "something to roll" and refers to the fact that thangkas can easily be rolled up for transportation.Besides thangkas, Tibetan Buddhist wall paintings can be found on temple walls as frescos and furniture and many other items have ornamental painting.

- Tibetan art

- Vajrasattva statue

- Coral prayer beads

Literature

There is a rich ancient tradition of lay Tibetan literature which includes epics, poetry, short stories, dance scripts and mime, plays and so on which has expanded into a huge body of work - some of which has been translated into Western languages. Tibetan literature has a historical span of over 1300 years. Perhaps the best known category of Tibetan literature outside of Tibet are the epic stories - particularly the famous Epic of King Gesar.Architecture

The White Palace of the Potala Palace

Tagong Monastery with prayer flags

The most unusual feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often made of a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against frequent earthquakes in the mountainous area.

World Heritage Site

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace, designated as a World Heritage site in 1994 and extended to include the Norbulingka area in 2001, is considered a most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lamas, it contains over a thousand rooms within thirteen stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided into the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures.Traditional architecture

Traditional Kham architecture is seen in most dwellings in Kangding. Kham houses tend to be spacious and fit in well with their environment. Their floors and ceilings are wooden, as houses are throughout in Kangding. [this article is dated. Modern Kangding city is now rebuilt, eliminating the earlier fire-prone wooden architecture]. Horizontal timber beams support the roof and these in turn are supported by wooden columns. Although the area has been heavily logged, wood is imported and used abundantly for housing. The Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Kham, surrounded by forests, is known for its beautiful wooden houses built in a range of styles and lavishly decorated with wooden ornamentation. The interiors of houses are usually paneled with wood and the cabinetry is ornately decorated. Although various materials are used in the well-built houses, it is the skilful carpentry that is striking. This skill is passed down from father to son and there appear to be plenty of carpenters. However a threat to traditional Tibetan carpentry is the growing use of concrete structures. Some consider the increased use of concrete as a deliberate infiltration of the Chinese influence into Tibet. In Gaba Township, where there are few Han Chinese, almost all the structures are traditional.Architecture and monastic architecture

Gyantse Kumbum, a good example of Dzong architecture

The events that took place in Tibet in the twentieth century exacted a heavy toll on Tibetan monastic architecture.

Under the 13th Dalai Lama, the Tengyeling monastery was demolished in 1914 for seeking to come to terms with the Chinese. Under Regent Taktra, the Sera monastery was bombarded with howitzers and ransacked by the Tibetan army in 1947 for siding with former regent Reting.

It is important to see that Sera monastery was by no means destroyed but only looted partially. The major destruction happened during the Cultural Revolution. China's Cultural Revolution resulted in the deterioration or loss of Buddhist monasteries, both by intentional destruction and through lack of protection and maintenance.

Starting in the 1980s, Tibetans have begun to restore those monasteries that survived. This has become an international effort. Experts are teaching the Tibetans how to restore the building and save the remaining monasteries on the eastern plateau.

Monasteries such as the Kumbum Monastery continue to be affected by Chinese politics. Simbiling Monastery was completely flattened in 1967, although it has to some degree been restored.

Tashi Lhunpo Monastery shows the influence of Mongol architecture. Tradruk Temple is one of the oldest in Tibet, said to have been first built in the 7th century during the reign of Songtsen Gampo of the Tibetan Empire (605?-650). Jokhang was also originally built under Songsten Gampo. Tsurphu Monastery was founded by Düsum Khyenpa, 1st Karmapa Lama (1110–1193) in 1159, after he visited the site and laid the foundation for an establishment of a seat there by making offerings to the local protectors, dharmapalas and genius loci. In 1189 he revisited the site and founded his main seat there. The monastery grew to hold 1000 monks. Tsozong Gongba Monastery is a small shrine built around the fourteenth century Palcho Monastery was founded in 1418 and known for its kumbum which has 108 chapels on its four floors. Chokorgyel Monastery, founded in 1509 the 2nd Dalai Lama once housed 500 monks but was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Ramoche Temple is an important temple in Lhasa. The original building complex was strongly influenced by Tang dynasty architectural style as it was first built by Han Chinese architects in the middle of the 7th century. Princess Wencheng took charge of this project and ordered the temple be erected facing east to show her homesickness.

- Tibetan monastic Architecture

- Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, reflects a style which would influence that of Mongol styles of architecture

- The Dalai Lama's Quarters in the Potala Palace

- Roof of the Jokhang

- Tibetan Architectural details

Clothing

Children

Tibetans tend to be conservative in their dress, and though some have taken to wearing Western clothes, traditional styles still abound. Women wear dark-colored wrap dresses over a blouse, and a colorfully striped, woven wool apron, called pangden signals that she is married. Men and women both wear long sleeves even in summer months.

In his 1955 book, Tibetan Marches, André Migot describes Tibetan clothing as follows:

Tibetan herdsman's coat, fur-lined. A portable shrine for worship was carried with a shoulder strap. Field Museum of Natural History

Except for the lamas and for certain laymen who shave their heads, the Tibetans wear their hair either long or in a braid wound around their heads and embellished with a complicated pattern of lesser braids which make the whole thing look like some sort of crown. They often wear a huge conical felt hat, whose shape varies according to the district they come from; sometimes its peak supports a kind of mortarboard from which dangles a thick woolen fringe. In order to prevent their hats being blown away, they attach them to their heads with the long braid I have just described, and which has to be unwound for the purpose. In their left ear they wear a heavy silver ring decorated with a huge ornament of either coral or turquoise. Their costume is not elaborate. It normally consists only of a chuba, a long capacious robe with wide, elongated sleeves which hang almost to the ground. This is caught up at the waist by a woolen girdle, so that its skirts reach only to the knees and its upper folds form an enormous circular pocket round its wearer's chest. This is called the ampa, and in it are stowed a wide range of implements — an eating bowl, a bag of tsampa, and many other small necessities. Many chubas are made of wool, either the plain gray wool they spin in Sikang or the splendid, warm, soft stuff from Lhasa, dyed a rich dark red. The nomads, on the other hand, generally wear a sheepskin chuba, hand-sewn and crudely tanned in butter, with the fleece on the inside. The town-dwelling Tibetans, prosperous merchants for the most part, supplement this garment with cotton or woolen drawers and a cotton or silk undershirt with long sleeves, but the nomads normally wear nothing at all underneath it, though in winter they sometimes put on sheepskin drawers. The Tibetans hardly ever do their chubas up over their chests. The right shoulder and arm are almost always left free, and when they are on the march or at work the whole top part of the robe is allowed to slip down so that it is supported only by the belt. This leaves them naked above the waist and clad in a very odd-looking sort of skirt below it. They hardly feel the cold at all and in the depth of winter, heedless of frost or snow or wind, they trudge imperturbably along with their bosoms bared to the icy blast. Their feet, too, are bare inside their great high boots. These have soft soles of raw, untanned leather; the loose-fitting leg of the boot, which may be red or black or green, has a sort of woolen garter around the top of it which is fastened to the leg above the knee with another, very brightly colored strip of woolen material.

— André Migot (1953), Tibetan Marches

- Tibetan people

- Young woman wearing a chuba

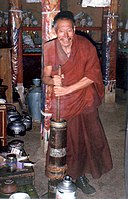

- Monk churning butter tea

- Monks at Sakya Monastery

- Tibetan women in the White House

- Tibetan people at the Tibet Nagqu Horse Racing Festival

- Woman from Kham

- Pilgrim with prayer wheel, Tsurphu Monastery, 1993

- Monks at Shigatse

- Young Monks in Litang County

- Tibetan woman with a prayer wheel praying

Cuisine

Thukpa is a Tibetan delicacy.

Butter tea

Tibetan kitchen items. The butter churn is of a small size with shoulder strap, suitable for nomadic life.

Mustard seed is cultivated in Tibet, and therefore features strongly in its cuisine. Yak yogurt, butter and cheese are frequently eaten, and well-prepared yogurt is considered something of a prestige item.

In larger Tibetan towns and cities many restaurants nowadays serve Sichuan-style Chinese food. Western imports and fusion dishes, such as fried yak and chips, are also popular. Nevertheless, many small restaurants serving traditional Tibetan dishes persist in both cities and the countryside.

Jasmine tea and yak butter tea are drunk. Alcoholic beverages include:

Tibetan family life

Tibetans traditionally venerate their elders within their families.Polyandry and polygyny

Tibetans used to practice polyandry widely. In his memoirs about his life in Tibet in the 1940s, Austrian writer Heinrich Harrer reports encountering nomads practising polyandry: "We were astonished to find polyandry practised among the nomads." "When several brothers share the same wife, the eldest is always the master in the household and the others have rights only when he is away or amusing himself elsewhere."Harrer also mentions the practice of polygyny in one particular case: a man marrying "several daughters of a house in which there is no son and heir." "The arrangement prevents the family fortune from being dispersed."

Calendar

Butter lamps

The Tibetan calendar is the lunisolar calendar, that is, the Tibetan year is composed of either 12 or 13 lunar months, each beginning and ending with a new moon. A thirteenth month is added approximately every three years, so that an average Tibetan year is equal to the solar year. The months have no names, but are referred to by their numbers except the fourth month which is called the saka dawa, celebrating the birth and enlightenment of Buddha.

The Tibetan New Year celebration is Losar.

Each year is associated with an animal and an element. The animals alternate in the following order:

| Rabbit | Dragon | Snake | Horse | Goat | Monkey | Rooster | Dog | Pig | Rat | Ox | Tiger |

The elements alternate in the following order:

| Fire | Earth | Iron | Water | Wood |

Each element is associated with two consecutive years, first in its male aspect, then in its female aspect. For example, a male Earth-Dragon year is followed by a female Earth-Snake year, then by a male Iron-Horse year. The sex may be omitted, as it can be inferred from the animal.

The element-animal designations recur in cycles of 60 years, starting with a (female) Fire-Rabbit year. These big cycles are numbered. The first cycle started in 1027. Therefore, 2005 roughly corresponds to the (female) Wood-Rooster year of the 17th cycle, and 2008 corresponds to a (male) Earth-Rat year of the same cycle.

Days of the week

Tibetan inscription on a stupa

Tent made of yak wool

| Day | Tibetan (Wylie) | THL | Object |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | གཟའ་ཉི་མ་ (gza' nyi ma) | za nyima | Sun |

| Monday | གཟའ་ཟླ་བ་ (gza' zla ba) | za dawa | Moon |

| Tuesday | གཟའ་མིག་དམར་ (gza' mig dmar) | za mikmar | Mars |

| Wednesday | གཟའ་ལྷག་པ་ (gza' lhak pa) | za lhakpa | Mercury |

| Thursday | གཟའ་ཕུར་པུ་ (gza' phur bu) | za purpu | Jupiter |

| Friday | གཟའ་པ་སངས་ (gza' pa sangs) | za pasang | Venus |

| Saturday | གཟའ་སྤེན་པ་ (gza' spen pa) | za penpa | Saturn |

Om mani padme hum, prayer written in Tibetan language

Nyima "Sun", Dawa "Moon" and Lhakpa "Mercury" are common personal names for people born on Sunday, Monday or Wednesday respectively.

Tibetan eras

- Rab byung: The first year of the first 60-year cycle is equivalent to AD 1027.

- Rab lo: The total number of years since 1027 are counted.

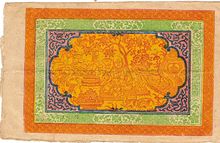

- Tibetan Era (used on Tibetan banknotes): The first year of this era is equivalent to AD 255.

- rgyal lo or bod rgyal lo: The first year of this era is equivalent to 127 BC.

Traditional gifts

Old Tibetan banknote

Tibetan coin

Censer from Tibet, late 19th century, silver

The khata is a highly versatile gift. It can be presented at any festive occasions to a host or at weddings, funerals, births, graduations, arrivals and departure of guests etc. The Tibetans commonly give a kind acknowledgment of "Tashi Delek" (meaning good luck) at the time of presenting.

A gift traditionally given at the time of a new birth is that of an ibex figurine, as described below by August Hermann Francke.

"Our Christian evangelist at Khalatse had become a father a few weeks before, and the people of the village had made presents of "flour-ibex" to him and his wife. He gave me one of those figures, which are made of flour and butter, and told me that it was a custom in Tibet and Ladakh, to make presents of "flour-ibex" on the occasion of the birth of a child. This is quite interesting information. I had often wondered why there were so many rock carvings of ibex at places connected with the pre-Buddhist religion of Ladakh. Now it appears probable that they are thank offerings after the birth of children. As I have tried to show in my previous article, people used to go to the pre-Buddhist places of worship, in particular, to pray to be blessed with children."

Performing arts

Music

Horn player monks

Musicians in Ladakh

Chanting

Tibetan music often involves chanting in Tibetan or Sanskrit as an integral part of the religion. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Other styles include those unique to the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the classical music of the popular Gelug school and the romantic music of the Nyingma, Sakya and Kagyu schools.Secular Tibetan music has been promoted by organizations like the 14th Dalai Lama's Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. This organization specialized in the lhamo, an operatic style, before branching out into other styles, including dance music like toeshey and nangma. Nangma is especially popular in the karaoke bars of the urban center of Tibet, Lhasa. Another form of popular music is the classical gar style, which is performed at rituals and ceremonies. Lu are a type of songs that feature glottal vibrations and high pitches which are typically sung by nomads. There are also epic bards who sing of Tibet's national hero, Gesar.

Modern and popular

Tibetans are well represented in Chinese popular culture. Tibetan singers are particularly known for their strong vocal abilities, which many attribute to the high altitudes of the Tibetan Plateau. Tseten Dolma (才旦卓玛) rose to fame in the 1960s for her music-and-dance suite "The Earth is Red". Kelsang Metok (格桑梅朵) is a popular singer who combines traditional Tibetan songs with elements of Chinese and Western pop. Purba Rgyal (Pubajia or 蒲巴甲) was the 2006 winner of Haonaner, the Chinese version of American Idol. In 2006, he starred in Sherwood Hu's Prince of the Himalayas, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Hamlet, set in ancient Tibet and featuring an all-Tibetan cast.Tibetan music has influenced certain styles of Western music, such as new-age. Philip Glass, Henry Eichheim and other composers are known for Tibetan elements in their music. The first Western fusion with Tibetan music was Tibetan Bells in 1971. The soundtrack to Kundun, by Glass, has also popularized Tibetan music in the West.

Foreign styles of popular music have also had a major impact within Tibet. Indian ghazal and filmi are very popular, as is rock and roll, an American style which has produced Tibetan performers like Rangzen Shonu. Since the relaxation of some laws in the 1980s, Tibetan pop, popularized by the likes of Yadong, Jampa Tsering, 3-member group AJIA, 4-member group Gao Yuan Hong, 5-member group Gao Yuan Feng, and Dechen Shak-Dagsay are well-known, as are the sometimes politicized lyrics of nangma. Gaoyuan Hong in particular has introduced elements of Tibetan language rapping into their singles.

Drama

The Tibetan folk opera known as (Ache) Lhamo "(sister) goddess", is a combination of dances, chants and songs. The repertoire is drawn from Buddhist stories and Tibetan history. Lhamo was founded in the fourteenth century by the Thang Tong Gyalpo, a lama and important historical civil engineer. Gyalpo and seven recruited girls organized the first performance to raise funds for building bridges that would facilitate transportation in Tibet. The tradition continued, and lhamo is held on various festive occasions such as the Linka and Shoton festivals.The performance is usually a drama, held on a barren stage, that combines dances, chants and songs. Colorful masks are sometimes worn to identify a character, with red symbolizing a king and yellow indicating deities and lamas.

The performance starts with a stage purification and blessings. A narrator then sings a summary of the story, and the performance begins. Another ritual blessing is conducted at the end of the play.

Festivals

Tibetan festivals such as Losar, Shoton, the Bathing Festival and many more are deeply rooted in indigenous religion, and also contain foreign influences. Tibetan festivals are a high source of entertainment and can include many sports such as yak racing. Tibetans consider festivals as an integral part of their life and almost everyone participates in the festivities.- Tibetan musicians

- A street musician in Shigatse

Domestic animals

- Tibetan Domestic animals

- Shepherd with his Tibetan Mastiff

- Domestic yak. In Tibet, yaks are decorated and honored by the families they are part of.

- A Lhasa Apso with a long, dense coat, a dog originating in Tibet.