Media bias is the bias or perceived bias of journalists and news producers within the mass media in the selection of events and stories that are reported and how they are covered. The term "media bias" implies a pervasive or widespread bias contravening the standards of journalism, rather than the perspective of an individual journalist or article. The direction and degree of media bias in various countries is widely disputed.

Practical limitations to media neutrality include the inability of journalists to report all available stories and facts, and the requirement that selected facts be linked into a coherent narrative. Government influence, including overt and covert censorship, biases the media in some countries, for example China, North Korea and Myanmar. Market forces that result in a biased presentation include the ownership of the news source, concentration of media ownership, the selection of staff, the preferences of an intended audience, and pressure from advertisers.

There are a number of national and international watchdog groups that report on bias in the media.

Types

The most commonly discussed forms of bias occur when the (allegedly partisan) media support or attack a particular political party, candidate, or ideology.D'Alessio and Allen list three forms of media bias as the most widely studied:

- Coverage bias (also known as visibility bias), when actors or issues are more or less visible in the news.

- Gatekeeping bias (also known as selectivity or selection bias), when stories are selected or deselected, sometimes on ideological grounds. It is sometimes also referred to as agenda bias, when the focus is on political actors and whether they are covered based on their preferred policy issues.

- Statement bias (also known as tonality bias or presentation bias), when media coverage is slanted towards or against particular actors or issues.

- Advertising bias, when stories are selected or slanted to please advertisers.

- Concision bias, a tendency to report views that can be summarized succinctly, crowding out more unconventional views that take time to explain.

- Corporate bias, when stories are selected or slanted to please corporate owners of media.

- Mainstream bias, a tendency to report what everyone else is reporting, and to avoid stories that will offend anyone.

- Sensationalism, bias in favor of the exceptional over the ordinary, giving the impression that rare events, such as airplane crashes, are more common than common events, such as automobile crashes.

- Structural bias, when an actor or issue receives more or less favorable coverage as a result of newsworthiness and media routines, not as the result of ideological decisions (e.g., incumbency bonus).

- False balance, when an issue is presented as even sided, despite disproportionate amounts of evidence.

- Undue Weight, when a story is given much greater significance or portent than a neutral journalist or editor would give.

- Speculative content, when stories focus not on what has occurred, but primarily on what might occur, using words like "could," "might," or "what if," without labeling the article as analysis or opinion.

- False Timeliness, implying that an event is a new event, and thus deriving notability, without addressing past events of the same kind.

- Ventriloquism, when experts or witnesses are quoted in a way that intentionally voices the author's own opinion.

United States

Media bias in the United States occurs when the media in the United States systematically emphasizes one particular point of view in a manner that contravenes the standards of professional journalism. Claims of media bias in the United States include claims of liberal bias, conservative bias, mainstream bias, and corporate bias and activist/cause bias. To combat this, a variety of watchdog groups that attempt to find the facts behind both biased reporting and unfounded claims of bias have been founded. These include:- Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), which has been described as both progressive and leaning left.

- Media Research Center (MRC), a conservative group, with the stated mission of which is to "prove—through sound scientific research—that liberal bias in the media does exist and undermines traditional American values."

Scholarly treatment in the United States and United Kingdom

Media bias is studied at schools of journalism, university departments (including Media studies, Cultural studies and Peace studies) and by independent watchdog groups from various parts of the political spectrum. In the United States, many of these studies focus on issues of a conservative/liberal balance in the media. Other focuses include international differences in reporting, as well as bias in reporting of particular issues such as economic class or environmental interests.Martin Harrison's TV News: Whose Bias? (1985) criticized the methodology of the Glasgow Media Group, arguing that the GMG identified bias selectively, via their own preconceptions about what phrases qualify as biased descriptions. For example, the GMG sees the word "idle" to describe striking workers as pejorative, despite the word being used by strikers themselves.

Herman and Chomsky (1988) proposed a propaganda model hypothesizing systematic biases of U.S. media from structural economic causes. They hypothesize media ownership by corporations, funding from advertising, the use of official sources, efforts to discredit independent media ("flak"), and "anti-communist" ideology as the filters that bias news in favor of U.S. corporate interests.

Many of the positions in the preceding study are supported by a 2002 study by Jim A. Kuypers: Press Bias and Politics: How the Media Frame Controversial Issues. In this study of 116 mainstream US papers (including The New York Times, the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle), Kuypers found that the mainstream print press in America operate within a narrow range of liberal beliefs. Those who expressed points of view further to the left were generally ignored, whereas those who expressed moderate or conservative points of view were often actively denigrated or labeled as holding a minority point of view. In short, if a political leader, regardless of party, spoke within the press-supported range of acceptable discourse, he or she would receive positive press coverage. If a politician, again regardless of party, were to speak outside of this range, he or she would receive negative press or be ignored. Kuypers also found that the liberal points of view expressed in editorial and opinion pages were found in hard news coverage of the same issues. Although focusing primarily on the issues of race and homosexuality, Kuypers found that the press injected opinion into its news coverage of other issues such as welfare reform, environmental protection, and gun control; in all cases favoring a liberal point of view.

Studies reporting perceptions of bias in the media are not limited to studies of print media. A joint study by the Joan Shorenstein Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University and the Project for Excellence in Journalism found that people see media bias in television news media such as CNN. Although both CNN and Fox were perceived in the study as not being centrist, CNN was perceived as being more liberal than Fox. Moreover, the study's findings concerning CNN's perceived bias are echoed in other studies. There is also a growing economics literature on mass media bias, both on the theoretical and the empirical side. On the theoretical side the focus is on understanding to what extent the political positioning of mass media outlets is mainly driven by demand or supply factors. This literature is surveyed by Andrea Prat of Columbia University and David Stromberg of Stockholm University.

According to Dan Sutter of the University of Oklahoma, a systematic liberal bias in the U.S. media could depend on the fact that owners and/or journalists typically lean to the left.

Along the same lines, David Baron of Stanford GSB presents a game-theoretic model of mass media behaviour in which, given that the pool of journalists systematically leans towards the left or the right, mass media outlets maximise their profits by providing content that is biased in the same direction. They can do so, because it is cheaper to hire journalists who write stories that are consistent with their political position. A concurrent theory would be that supply and demand would cause media to attain a neutral balance because consumers would of course gravitate towards the media they agreed with. This argument fails in considering the imbalance in self-reported political allegiances by journalists themselves, that distort any market analogy as regards offer: (..) Indeed, in 1982, 85 percent of Columbia Graduate School of Journalism students identified themselves as liberal, versus 11 percent conservative" (Lichter, Rothman, and Lichter 1986: 48), quoted in Sutter, 2001.

This same argument would have news outlets in equal numbers increasing profits of a more balanced media far more than the slight increase in costs to hire unbiased journalists, notwithstanding the extreme rarity of self-reported conservative journalists (Sutton, 2001).

As mentioned above, Tim Groseclose of UCLA and Jeff Milyo of the University of Missouri at Columbia use think tank quotes, in order to estimate the relative position of mass media outlets in the political spectrum. The idea is to trace out which think tanks are quoted by various mass media outlets within news stories, and to match these think tanks with the political position of members of the U.S. Congress who quote them in a non-negative way. Using this procedure, Groseclose and Milyo obtain the stark result that all sampled news providers -except Fox News' Special Report and the Washington Times- are located to the left of the average Congress member, i.e. there are signs of a liberal bias in the US news media. However, the news media also show a remarkable degree of centrism, just because all outlets but one are located –from an ideological point of view- between the average Democrat and average Republican in Congress.

The methods Groseclose and Milyo used to calculate this bias have been criticized by Mark Liberman, a professor of Linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania. Liberman concludes by saying he thinks "that many if not most of the complaints directed against G&M are motivated in part by ideological disagreement – just as much of the praise for their work is motivated by ideological agreement. It would be nice if there were a less politically fraught body of data on which such modeling exercises could be explored."

Sendhil Mullainathan and Andrei Shleifer of Harvard University construct a behavioural model, which is built around the assumption that readers and viewers hold beliefs that they would like to see confirmed by news providers. When news customers share common beliefs, profit-maximizing media outlets find it optimal to select and/or frame stories in order to pander to those beliefs. On the other hand, when beliefs are heterogeneous, news providers differentiate their offer and segment the market, by providing news stories that are slanted towards the two extreme positions in the spectrum of beliefs.

Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse Shapiro of Chicago GSB present another demand-driven theory of mass media bias. If readers and viewers have a priori views on the current state of affairs and are uncertain about the quality of the information about it being provided by media outlets, then the latter have an incentive to slant stories towards their customers' prior beliefs, in order to build and keep a reputation for high-quality journalism. The reason for this is that rational agents would tend to believe that pieces of information that go against their prior beliefs in fact originate from low-quality news providers.

Given that different groups in society have different beliefs, priorities, and interests, to which group would the media tailor its bias? David Stromberg constructs a demand-driven model where media bias arises because different audiences have different effects on media profits. Advertisers pay more for affluent audiences and media may tailor content to attract this audience, perhaps producing a right-wing bias. On the other hand, urban audiences are more profitable to newspapers because of lower delivery costs. Newspapers may for this reason tailor their content to attract the profitable predominantly liberal urban audiences. Finally, because of the increasing returns to scale in news production, small groups such as minorities are less profitable. This biases media content against the interest of minorities.

Jimmy Chan of Shanghai University and Wing Suen of the University of Hong Kong develop a model where media bias arises because the media cannot tell "the whole truth" but are restricted to simple messages, such as political endorsements. In this setting, media bias arises because biased media are more informative; people with a certain political bias prefer media with a similar bias because they can more trust their advice on what actions to take.

The economics empirical literature on mass media bias mainly focuses on the United States.

Steve Ansolabehere, Rebecca Lessem and Jim Snyder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyze the political orientation of endorsements by U.S. newspapers. They find an upward trend in the average propensity to endorse a candidate, and in particular an incumbent one. There are also some changes in the average ideological slant of endorsements: while in the 1940s and in the 1950s there was a clear advantage to Republican candidates, this advantage continuously eroded in subsequent decades, to the extent that in the 1990s the authors find a slight Democratic lead in the average endorsement choice.

John Lott and Kevin Hassett of the American Enterprise Institute study the coverage of economic news by looking at a panel of 389 U.S. newspapers from 1991 to 2004, and from 1985 to 2004 for a subsample comprising the top 10 newspapers and the Associated Press. For each release of official data about a set of economic indicators, the authors analyze how newspapers decide to report on them, as reflected by the tone of the related headlines. The idea is to check whether newspapers display some kind of partisan bias, by giving more positive or negative coverage to the same economic figure, as a function of the political affiliation of the incumbent president. Controlling for the economic data being released, the authors find that there are between 9.6 and 14.7 percent fewer positive stories when the incumbent president is a Republican.

Riccardo Puglisi of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looks at the editorial choices of the New York Times from 1946 to 1997. He finds that the Times displays Democratic partisanship, with some watchdog aspects. This is the case, because during presidential campaigns the Times systematically gives more coverage to Democratic topics of civil rights, health care, labor and social welfare, but only when the incumbent president is a Republican. These topics are classified as Democratic ones, because Gallup polls show that on average U.S. citizens think that Democratic candidates would be better at handling problems related to them. According to Puglisi, in the post-1960 period the Times displays a more symmetric type of watchdog behaviour, just because during presidential campaigns it also gives more coverage to the typically Republican issue of Defense when the incumbent president is a Democrat, and less so when the incumbent is a Republican.

Alan Gerber and Dean Karlan of Yale University use an experimental approach to examine not whether the media are biased, but whether the media influence political decisions and attitudes. They conduct a randomized control trial just prior to the November 2005 gubernatorial election in Virginia and randomly assign individuals in Northern Virginia to (a) a treatment group that receives a free subscription to the Washington Post, (b) a treatment group that receives a free subscription to the Washington Times, or (c) a control group. They find that those who are assigned to the Washington Post treatment group are eight percentage points more likely to vote for the Democrat in the elections. The report also found that "exposure to either newspaper was weakly linked to a movement away from the Bush administration and Republicans."

Another unaffiliated group, Media Study Group, established seven categories of poor journalistic practice: for example, the journalist stating personal opinion in a report, asserting incorrect facts, applying unequal space or treatment to two sides of a controversial issue; then analyzed The Age Newspaper (Melbourne Australia) for the frequency of infraction of this code of practice. The resultant instances were then analyzed statistically with respect to the frequency they supported one or other side of the two-sided controversial issue under consideration. The goal of this group was to establish a quantitative methodology for the study of bias.

A self-described "progressive" media watchdog group, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), in consultation with the Survey and Evaluation Research Laboratory at Virginia Commonwealth University, sponsored a 1998 survey in which 141 Washington bureau chiefs and Washington-based journalists were asked a range of questions about how they did their work and about how they viewed the quality of media coverage in the broad area of politics and economic policy. "They were asked for their opinions and views about a range of recent policy issues and debates. Finally, they were asked for demographic and identifying information, including their political orientation". They then compared to the same or similar questions posed with "the public" based on Gallup, and Pew Trust polls. Their study concluded that a majority of journalists, although relatively liberal on social policies, were significantly to the right of the public on economic, labor, health care and foreign policy issues.

This study continues: "we learn much more about the political orientation of news content by looking at sourcing patterns rather than journalists' personal views. As this survey shows, it is government officials and business representatives to whom journalists "nearly always" turn when covering economic policy. Labor representatives and consumer advocates were at the bottom of the list. This is consistent with earlier research on sources. For example, analysts from the non-partisan Brookings Institution and from conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute are those most quoted in mainstream news accounts.

In direct contrast to the FAIR survey, in 2014, media communication researcher Jim A. Kuypers published a 40-year longitudinal, aggregate study of the political beliefs and actions of American journalists. In every single category (for instance, social, economic, unions, health care, and foreign policy) he found that nationwide, print and broadcast journalists and editors as a group were "considerably" to the political left of the majority of Americans, and that these political beliefs found their way into news stories. Kuypers concluded, "Do the political proclivities of journalists influence their interpretation of the news? I answer that with a resounding, yes. As part of my evidence, I consider testimony from journalists themselves. ... [A] solid majority of journalists do allow their political ideology to influence their reporting."

Jonathan M. Ladd, who has conducted intensive studies of media trust and media bias, concluded that the primary cause of belief in media bias is media telling their audience that particular media are biased. People who are told that a medium is biased tend to believe that it is biased, and this belief is unrelated to whether that medium is actually biased or not. The only other factor with as strong an influence on belief that media is biased is extensive coverage of celebrities. A majority of people see such media as biased, while at the same time preferring media with extensive coverage of celebrities.

Experimenter's bias

A major problem in studies is experimenter's bias. Research into studies of media bias in the United States shows that liberal experimenters tend to get results that say the media has a conservative bias, while conservatives experimenters tend to get results that say the media has a liberal bias, and those who do not identify themselves as either liberal or conservative get results indicating little bias, or mixed bias.The study "A Measure of Media Bias" by political scientist Timothy J. Groseclose of UCLA and economist Jeffrey D. Milyo of the University of Missouri-Columbia, purports to rank news organizations in terms of identifying with liberal or conservative values relative to each other. They used the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) scores as a quantitative proxy for political leanings of the referential organizations. Thus their definition of "liberal" includes the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research organization with strong ties to the Defense Department. Their work claims to detect a bias towards liberalism in the American media.

Efforts to correct bias

A technique used to avoid bias is the "point/counterpoint" or "round table", an adversarial format in which representatives of opposing views comment on an issue. This approach theoretically allows diverse views to appear in the media. However, the person organizing the report still has the responsibility to choose people who really represent the breadth of opinion, to ask them non-prejudicial questions, and to edit or arbitrate their comments fairly. When done carelessly, a point/counterpoint can be as unfair as a simple biased report, by suggesting that the "losing" side lost on its merits.Using this format can also lead to accusations that the reporter has created a misleading appearance that viewpoints have equal validity (sometimes called "false balance"). This may happen when a taboo exists around one of the viewpoints, or when one of the representatives habitually makes claims that are easily shown to be inaccurate.

One such allegation of misleading balance came from Mark Halperin, political director of ABC News. He stated in an internal e-mail message that reporters should not "artificially hold George W. Bush and John Kerry 'equally' accountable" to the public interest, and that complaints from Bush supporters were an attempt to "get away with ... renewed efforts to win the election by destroying Senator Kerry." When the conservative web site the Drudge Report published this message, many Bush supporters viewed it as "smoking gun" evidence that Halperin was using ABC to propagandize against Bush to Kerry's benefit, by interfering with reporters' attempts to avoid bias. An academic content analysis of election news later found that coverage at ABC, CBS, and NBC was more favorable toward Kerry than Bush, while coverage at Fox News Channel was more favorable toward Bush.

Scott Norvell, the London bureau chief for Fox News, stated in a May 20, 2005 interview with the Wall Street Journal that:

"Even we at Fox News manage to get some lefties on the air occasionally, and often let them finish their sentences before we club them to death and feed the scraps to Karl Rove and Bill O'Reilly. And those who hate us can take solace in the fact that they aren't subsidizing Bill's bombast; we payers of the BBC license fee don't enjoy that peace of mind.Another technique used to avoid bias is disclosure of affiliations that may be considered a possible conflict of interest. This is especially apparent when a news organization is reporting a story with some relevancy to the news organization itself or to its ownership individuals or conglomerate. Often this disclosure is mandated by the laws or regulations pertaining to stocks and securities. Commentators on news stories involving stocks are often required to disclose any ownership interest in those corporations or in its competitors.

Fox News is, after all, a private channel and our presenters are quite open about where they stand on particular stories. That's our appeal. People watch us because they know what they are getting. The Beeb's (British Broadcasting Corporation) (BBC) institutionalized leftism would be easier to tolerate if the corporation was a little more honest about it".

In rare cases, a news organization may dismiss or reassign staff members who appear biased. This approach was used in the Killian documents affair and after Peter Arnett's interview with the Iraqi press. This approach is presumed to have been employed in the case of Dan Rather over a story that he ran on 60 Minutes in the month prior to the 2004 election that attempted to impugn the military record of George W. Bush by relying on allegedly fake documents that were provided by Bill Burkett, a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the Texas Army National Guard.

Finally, some countries have laws enforcing balance in state-owned media. Since 1991, the CBC and Radio Canada, its French language counterpart, are governed by the Broadcasting Act. This act states, among other things:

the programming provided by the Canadian broadcasting system shouldBesides these manual approaches, several (semi-)automated approaches have been developed by social scientists and computer scientists. These approaches identify differences in news coverage, which potentially resulted from media bias, by analyzing the text and meta data, such as author and publishing date. For instance, NewsCube is a news aggregator that extracts key phrases that describe a topic differently. Other approaches make use of text- and meta-data, e.g., matrix-based news aggregation spans a matrix over two dimensions, such as publisher countries (in which articles have been published) and mentioned countries (on which country an article reports). As a result, each cell contains only articles that have been published in one country and that report on another country. Particularly in international news topics, matrix-based news aggregation helps to reveal differences in media coverage between the involved countries.

(i) be varied and comprehensive, providing a balance of information, enlightenment and entertainment for men, women and children of all ages, interests and tastes, (...)

(iv) provide a reasonable opportunity for the public to be exposed to the expression of differing views on matters of public concern

History

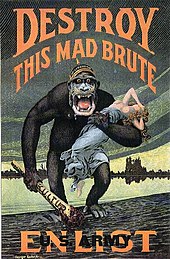

Political bias has been a feature of the mass media since its birth with the invention of the printing press. The expense of early printing equipment restricted media production to a limited number of people. Historians have found that publishers often served the interests of powerful social groups.John Milton's pamphlet Areopagitica, a Speech for the Liberty of Unlicensed Printing, published in 1644, was one of the first publications advocating freedom of the press.

In the 19th century, journalists began to recognize the concept of unbiased reporting as an integral part of journalistic ethics. This coincided with the rise of journalism as a powerful social force. Even today, though, the most conscientiously objective journalists cannot avoid accusations of bias.

Like newspapers, the broadcast media (radio and television) have been used as a mechanism for propaganda from their earliest days, a tendency made more pronounced by the initial ownership of broadcast spectrum by national governments. Although a process of media deregulation has placed the majority of the western broadcast media in private hands, there still exists a strong government presence, or even monopoly, in the broadcast media of many countries across the globe. At the same time, the concentration of media ownership in private hands, and frequently amongst a comparatively small number of individuals, has also led to accusations of media bias.

There are many examples of accusations of bias being used as a political tool, sometimes resulting in government censorship.

- In the United States, in 1798, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which prohibited newspapers from publishing "false, scandalous, or malicious writing" against the government, including any public opposition to any law or presidential act. This act was in effect until 1801.

- During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln accused newspapers in the border states of bias in favor of the Southern cause, and ordered many newspapers closed.

- Anti-Semitic politicians who favored the United States entering World War II on the Nazi side asserted that the international media were controlled by Jews, and that reports of German mistreatment of Jews were biased and without foundation. Hollywood was accused of Jewish bias, and films such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator were offered as alleged proof.

- In the 1980s, the South African government accused newspapers of liberal bias and instituted government censorship. In 1989, the newspaper New Nation was closed by the government for three months for publishing anti-apartheid propaganda. Other newspapers were not closed, but were extensively censored.

- In the US during the labor union movement and the civil rights movement, newspapers supporting liberal social reform were accused by conservative newspapers of communist bias. Film and television media were accused of bias in favor of mixing of the races, and many television programs with racially mixed casts, such as I Spy and Star Trek, were not aired on Southern stations.

- During the war between the United States and North Vietnam, Vice President Spiro Agnew accused newspapers of anti-American bias, and in a famous speech delivered in San Diego in 1970, called anti-war protesters "the nattering nabobs of negativism."

Role of language

Mass media, despite its ability to project worldwide, is limited in its cross-ethnic compatibility by one simple attribute – language. Ethnicity, being largely developed by a divergence in geography, language, culture, genes and similarly, point of view, has the potential to be countered by a common source of information. Therefore, language, in the absence of translation, comprises a barrier to a worldwide community of debate and opinion, although it is also true that media within any given society may be split along class, political or regional lines. Furthermore, if the language is translated, the translator has room to shift a bias by choosing weighed words for translation.Language may also be seen as a political factor in mass media, particularly in instances where a society is characterized by a large number of languages spoken by its populace. The choice of language of mass media may represent a bias towards the group most likely to speak that language, and can limit the public participation by those who do not speak the language. On the other hand, there have also been attempts to use a common-language mass media to reach out to a large, geographically dispersed population, such as in the use of Arabic language by news channel Al Jazeera.

Many media theorists concerned with language and media bias point towards the media of the United States, a large country where English is spoken by the majority of the population. Some theorists argue that the common language is not homogenizing; and that there still remain strong differences expressed within the mass media. This viewpoint asserts that moderate views are bolstered by drawing influences from the extremes of the political spectrum. In the United States, the national news therefore contributes to a sense of cohesion within the society, proceeding from a similarly informed population. According to this model, most views within society are freely expressed, and the mass media are accountable to the people and tends to reflect the spectrum of opinion.

Language may also introduce a more subtle form of bias. The selection of metaphors and analogies, or the inclusion of personal information in one situation but not another can introduce bias, such as a gender bias. Use of a word with positive or negative connotations rather than a more neutral synonym can form a biased picture in the audience's mind. For example, it makes a difference whether the media calls a group "terrorists" or "freedom fighters" or "insurgents". A 2005 memo to the staff of the CBC states:

- Rather than calling assailants "terrorists," we can refer to them as bombers, hijackers, gunmen (if we're sure no women were in the group), militants, extremists, attackers or some other appropriate noun.

National and ethnic viewpoint

Many news organizations reflect, or are perceived to reflect in some way, the viewpoint of the geographic, ethnic, and national population that they primarily serve. Media within countries are sometimes seen as being sycophantic or unquestioning about the country's government.Western media are often criticized in the rest of the world (including eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East) as being pro-Western with regard to a variety of political, cultural and economic issues. Al Jazeera is frequently criticized both in the West and in the Arab world.

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict and wider Arab–Israeli issues are a particularly controversial area, and nearly all coverage of any kind generates accusation of bias from one or both sides. This topic is covered in a separate article.

Anglophone bias in the world media

It has been observed that the world's principal suppliers of news, the news agencies, and the main buyers of news are Anglophone corporations and this gives an Anglophone bias to the selection and depiction of events. Anglophone definitions of what constitutes news are paramount; the news provided originates in Anglophone capitals and responds first to their own rich domestic markets.Despite the plethora of news services, most news printed and broadcast throughout the world each day comes from only a few major agencies, the three largest of which are the Associated Press, Reuters and Agence France-Presse. Although these agencies are 'global' in the sense of their activities, they each retain significant associations with particular nations, namely the United States (AP), the United Kingdom (Reuters) and France (AFP). Chambers and Tinckell suggest that the so-called global media are agents of Anglophone values which privilege norms of 'competitive individualism, laissez-faire capitalism, parliamentary democracy and consumerism.' They see the presentation of the English language as international as a further feature of Anglophone dominance.

Religious bias

The media are often accused of bias favoring a particular religion or of bias against a particular religion. In some countries, only reporting approved by a state religion is permitted. In other countries, derogatory statements about any belief system are considered hate crimes and are illegal.According to the Encyclopedia of Social Work (19th edition), the news media play an influential role in the general public's perception of cults. As reported in several studies, the media have depicted cults as problematic, controversial, and threatening from the beginning, tending to favor sensationalistic stories over balanced public debates. It furthers the analysis that media reports on cults rely heavily on police officials and cult "experts" who portray cult activity as dangerous and destructive, and when divergent views are presented, they are often overshadowed by horrific stories of ritualistic torture, sexual abuse, mind control, and other such practices. Furthermore, unfounded allegations, when proved untrue, receive little or no media attention.

In 2012, Huffington Post, columnist Jacques Berlinerblau argued that secularism has often been misinterpreted in the media as another word for atheism, stating that: "Secularism must be the most misunderstood and mangled ism in the American political lexicon. Commentators on the right and the left routinely equate it with Stalinism, Nazism and Socialism, among other dreaded isms. In the United States, of late, another false equation has emerged. That would be the groundless association of secularism with atheism. The religious right has profitably promulgated this misconception at least since the 1970s."

According to Stuart A. Wright, there are six factors that contribute to media bias against minority religions: first, the knowledge and familiarity of journalists with the subject matter; second, the degree of cultural accommodation of the targeted religious group; third, limited economic resources available to journalists; fourth, time constraints; fifth, sources of information used by journalists; and finally, the frond-end/back-end disproportionality of reporting. According to Yale Law professor Stephen Carter, "it has long been the American habit to be more suspicious of—and more repressive toward—religions that stand outside the mainline Protestant-Roman Catholic-Jewish troika that dominates America's spiritual life." As for front-end/back-end disproportionality, Wright says: "news stories on unpopular or marginal religions frequently are predicated on unsubstantiated allegations or government actions based on faulty or weak evidence occurring at the front-end of an event. As the charges weighed in against material evidence, these cases often disintegrate. Yet rarely is there equal space and attention in the mass media given to the resolution or outcome of the incident. If the accused are innocent, often the public is not made aware."

Other influences

The apparent bias of media is not always specifically political in nature. The news media tend to appeal to a specific audience, which means that stories that affect a large number of people on a global scale often receive less coverage in some markets than local stories, such as a public school shooting, a celebrity wedding, a plane crash, a "missing white woman", or similarly glamorous or shocking stories. For example, the deaths of millions of people in an ethnic conflict in Africa might be afforded scant mention in American media, while the shooting of five people in a high school is analyzed in depth. Bias is also known to exist in sports broadcasting; in the United States, broadcasters tend to favor teams on the East Coast, teams in major markets, older and more established teams and leagues, teams based in their respective country (in international sport) and teams that include high-profile celebrity athletes. The reason for these types of bias is a function of what the public wants to watch and/or what producers and publishers believe the public wants to watch.Bias has also been claimed in instances referred to as conflict of interest, whereby the owners of media outlets have vested interests in other commercial enterprises or political parties. In such cases in the United States, the media outlet is required to disclose the conflict of interest.

However, the decisions of the editorial department of a newspaper and the corporate parent frequently are not connected, as the editorial staff retains freedom to decide what is covered as well as what is not. Biases, real or implied, frequently arise when it comes to deciding what stories will be covered and who will be called for those stories.

Accusations that a source is biased, if accepted, may cause media consumers to distrust certain kinds of statements, and place added confidence on others.

How People View The Media: Two-thirds (67%) said agreed with the statement: "In dealing with political and social issues, news organizations tend to favor one side." That was up 14 points from 53 percent who gave that answer in 1985. Those who believed the media "deal fairly with all sides" fell from 34 percent to 27 percent. "In one of the most telling complaints, a majority (54%) of Americans believe the news media gets in the way of society solving its problems," Pew reported. Republicans "are more likely to say news organizations favor one side than are Democrats or independents (77 percent vs. 58 percent and 69 percent, respectively)." The percentage who felt "news organizations get the facts straight" fell from 55 percent to 37 percent.