| Voltaire | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière, c. 1724

| |

| Born |

François-Marie Arouet 21 November 1694 Paris, France |

| Died |

30 May 1778 (aged 83) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris, France |

| Pen name | Voltaire |

| Occupation | Writer, philosopher |

| Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Collège Louis-le-Grand |

| Partner | Émilie du Châtelet (1733–1749) |

Philosophy career | |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region |

Western philosophy French philosophy |

| School |

Lumières Philosophes Deism Classical liberalism |

Main interests

| Political philosophy, literature, historiography, biblical criticism |

Notable ideas

| Philosophy of history, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, separation of church and state |

François-Marie Arouet (French: [fʁɑ̃swa maʁi aʁwɛ]; 21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778), known by his nom de plume Voltaire (/voʊlˈtɛər/; French: [vɔltɛːʁ]), was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit, his criticism of Christianity, especially the Catholic Church, and his advocacy of freedom of religion, freedom of speech and separation of church and state.

Voltaire was a versatile and prolific writer, producing works in almost every literary form, including plays, poems, novels, essays and historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken advocate of civil liberties, despite the risk this placed him in under the strict censorship laws of the time. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma and the French institutions of his day.

Biography

By the time he left school, Voltaire had decided he wanted to be a writer, against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to become a lawyer. Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a notary, spent much of his time writing poetry. When his father found out, he sent Voltaire to study law, this time in Caen, Normandy. But the young man continued to write, producing essays and historical studies. Voltaire's wit made him popular among some of the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. In 1713, his father obtained a job for him as a secretary to the new French ambassador in the Netherlands, the marquis de Châteauneuf, the brother of Voltaire's godfather. At The Hague, Voltaire fell in love with a French Protestant refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer (known as 'Pimpette'). Their affair, considered scandalous, was discovered by de Châteauneuf and Voltaire was forced to return to France by the end of the year.

Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille from 16 May 1717 to 15 April 1718 in a windowless cell with ten-foot thick walls.

He mainly argued for religious tolerance and freedom of thought. He campaigned to eradicate priestly and aristo-monarchical authority, and supported a constitutional monarchy that protects people's rights.

Adopts the name Voltaire

The author adopted the name Voltaire in 1718, following his incarceration at the Bastille. Its origin is unclear. It is an anagram of AROVET LI, the Latinized spelling of his surname, Arouet, and the initial letters of le jeune ("the young"). According to a family tradition among the descendants of his sister, he was known as le petit volontaire ("determined little thing") as a child, and he resurrected a variant of the name in his adult life. The name also reverses the syllables of Airvault, his family's home town in the Poitou region.Richard Holmes supports the anagrammatic derivation of the name, but adds that a writer such as Voltaire would have intended it to also convey connotations of speed and daring. These come from associations with words such as voltige (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), volte-face (a spinning about to face one's enemies), and volatile (originally, any winged creature). "Arouet" was not a noble name fit for his growing reputation, especially given that name's resonance with à rouer ("to be beaten up") and roué (a débauché).

In a letter to Jean-Baptiste Rousseau in March 1719, Voltaire concludes by asking that, if Rousseau wishes to send him a return letter, he do so by addressing it to Monsieur de Voltaire. A postscript explains: "J'ai été si malheureux sous le nom d'Arouet que j'en ai pris un autre surtout pour n'être plus confondu avec le poète Roi", (I was so unhappy under the name of Arouet that I have taken another, primarily so as to cease to be confused with the poet Roi.) This probably refers to Adenes le Roi, and the 'oi' diphthong was then pronounced like modern 'ouai', so the similarity to 'Arouet' is clear, and thus, it could well have been part of his rationale. Voltaire is known also to have used at least 178 separate pen names during his lifetime.

La Henriade and Mariamne

Voltaire's next play, Artémire, set in ancient Macedonia, opened on 15 February 1720. It was a flop and only fragments of the text survive. He instead turned to an epic poem about Henry IV of France that he had begun in early 1717. Denied a licence to publish, in August 1722 Voltaire headed north to find a publisher outside France. On the journey, he was accompanied by his mistress, Marie-Marguerite de Rupelmonde, a young widow.At Brussels, Voltaire and Rousseau met up for a few days, before Voltaire and his mistress continued northwards. A publisher was eventually secured in The Hague. In the Netherlands, Voltaire was struck and impressed by the openness and tolerance of Dutch society. On his return to France, he secured a second publisher in Rouen, who agreed to publish La Henriade clandestinely. After Voltaire's recovery from a month-long smallpox infection in November 1723, the first copies were smuggled into Paris and distributed. While the poem was an instant success, Voltaire's new play, Mariamne, was a failure when it first opened in March 1724. Heavily reworked, it opened at the Comédie-Française in April 1725 to a much-improved reception. It was among the entertainments provided at the wedding of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńska in September 1725.

Great Britain

In early 1726, a young French nobleman, the chevalier de Rohan-Chabot, taunted Voltaire about his change of name, and Voltaire retorted that his name would be honoured while de Rohan would dishonour his. Infuriated, de Rohan arranged for Voltaire to be beaten up by thugs a few days later. Seeking compensation, redress, or revenge, Voltaire challenged de Rohan to a duel, but the aristocratic de Rohan family arranged for Voltaire to be arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille on 17 April 1726 without a trial or an opportunity to defend himself. Fearing an indefinite prison sentence, Voltaire suggested that he be exiled to England as an alternative punishment, which the French authorities accepted. On 2 May, he was escorted from the Bastille to Calais, where he was to embark for Britain.

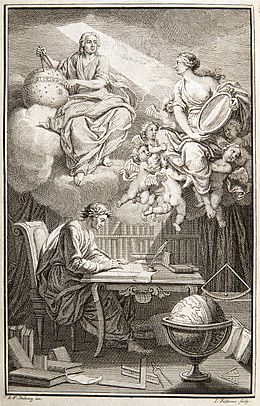

Elémens de la philosophie de Neuton, 1738

In England, Voltaire lived largely in Wandsworth, with acquaintances including Everard Fawkener. From December 1727 to June 1728 he lodged at Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, now commemorated by a plaque, to be nearer to his British publisher. Voltaire circulated throughout English high society, meeting Alexander Pope, John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and many other members of the nobility and royalty. Voltaire's exile in Great Britain greatly influenced his thinking. He was intrigued by Britain's constitutional monarchy in contrast to French absolutism, and by the country's greater support of the freedoms of speech and religion. He was influenced by the writers of the age, and developed an interest in earlier English literature, especially the works of Shakespeare, still relatively unknown in continental Europe. Despite pointing out his deviations from neoclassical standards, Voltaire saw Shakespeare as an example that French writers might emulate, since French drama, despite being more polished, lacked on-stage action. Later, however, as Shakespeare's influence began growing in France, Voltaire tried to set a contrary example with his own plays, decrying what he considered Shakespeare's barbarities. Voltaire may have been present at the funeral of Isaac Newton, and met Newton's niece, Catherine Conduitt. In 1727, he published two essays in English, Upon the Civil Wars of France, Extracted from Curious Manuscripts and Upon Epic Poetry of the European Nations, from Homer Down to Milton.

After two and a half years in exile, Voltaire returned to France, and after a few months living in Dieppe, the authorities permitted him to return to Paris. At a dinner, French mathematician Charles Marie de La Condamine proposed buying up the lottery that was organized by the French government to pay off its debts, and Voltaire joined the consortium, earning perhaps a million livres. He invested the money cleverly and on this basis managed to convince the Court of Finances that he was of good conduct and so was able to take control of a capital inheritance from his father that had hitherto been tied up in trust. He was now indisputably rich.

Further success followed, in 1732, with his play Zaïre, which when published in 1733 carried a dedication to Fawkener that praised English liberty and commerce. At this time he published his views on British attitudes toward government, literature, religion and science in a collection of essays in letter form entitled Letters Concerning the English Nation (London, 1733). In 1734, they were published in French as Lettres philosophiques in Rouen. Because the publisher released the book without the approval of the royal censor and Voltaire regarded the British constitutional monarchy as more developed and more respectful of human rights (particularly religious tolerance) than its French counterpart, the French publication of Letters caused a huge scandal; the book was publicly burnt and banned, and Voltaire was forced again to flee Paris.

Château de Cirey

In the frontispiece to Voltaire's book on Newton's philosophy, Émilie du Châtelet appears as Voltaire's muse, reflecting Newton's heavenly insights down to Voltaire.

Having learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began his habit of keeping out of personal harm's way and denying any awkward responsibility. He continued to write plays, such as Mérope (or La Mérope française) and began his long research into science and history. Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire were the years of his British exile, during which he had been strongly influenced by the works of Sir Isaac Newton. Voltaire strongly believed in Newton's theories; he performed experiments in optics at Cirey, and was one of the sources for the famous story of Newton and the apple falling from the tree, which he had learned from Newton's niece in London and first mentioned in his Letters.

Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1735

In the fall of 1735, Voltaire was visited by Francesco Algarotti, who was preparing a book about Newton in Italian. Partly inspired by the visit, the Marquise translated Newton's Latin Principia into French in full, and it remained the definitive French translation into the 21st century. Both she and Voltaire were also curious about the philosophies of Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary and rival of Newton. While Voltaire remained a firm Newtonian, the Marquise adopted certain aspects of Leibniz's arguments against Newton. Voltaire's own book Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (Elements of Newton's Philosophy) made Newton accessible and understandable to a far greater public, and the Marquise wrote a celebratory review in the Journal des savants. Voltaire's work was instrumental in bringing about general acceptance of Newton's optical and gravitational theories in France.

Voltaire and the Marquise also studied history, particularly those persons who had contributed to civilization. Voltaire's second essay in English had been "Essay upon the Civil Wars in France". It was followed by La Henriade, an epic poem on the French King Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, and by a historical novel on King Charles XII of Sweden. These, along with his Letters on the English mark the beginning of Voltaire's open criticism of intolerance and established religions. Voltaire and the Marquise also explored philosophy, particularly metaphysics, the branch of philosophy that deals with being and with what lies beyond the material realm, such as whether or not there is a God and whether people have souls. Voltaire and the Marquise analysed the Bible and concluded that much of its content was dubious. Voltaire's critical views on religion are reflected in his belief in separation of church and state and religious freedom, ideas that he had formed after his stay in England.

In August 1736, Frederick the Great, then Crown Prince of Prussia and a great admirer of Voltaire, initiated a correspondence with him. That December, Voltaire moved to Holland for two months and became acquainted with the scientists Herman Boerhaave and 's Gravesande. From mid-1739 to mid-1740 Voltaire lived largely in Brussels, at first with the Marquise, who was unsuccessfully attempting to pursue a 60-year-old family legal case regarding the ownership of two estates in Limburg. In July 1740, he traveled to the Hague on behalf of Frederick in an attempt to dissuade a dubious publisher, van Duren, from printing without permission Frederick's Anti-Machiavel. In September Voltaire and Frederick (now King) met for the first time in Moyland Castle near Cleves and in November Voltaire was Frederick's guest in Berlin for two weeks; in September 1742 they met in Aix-la-Chapelle. Voltaire was sent to Frederick's court in 1743 by the French government as an envoy and spy to gauge Frederick's military intentions in the War of the Austrian Succession.

Though deeply committed to the Marquise, Voltaire by 1744 found life at the château confining. On a visit to Paris that year, he found a new love—his niece. At first, his attraction to Marie Louise Mignot was clearly sexual, as evidenced by his letters to her (only discovered in 1957). Much later, they lived together, perhaps platonically, and remained together until Voltaire's death. Meanwhile, the Marquise also took a lover, the Marquis de Saint-Lambert.

Prussia

Die Tafelrunde by Adolph von Menzel: guests of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci, including members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Voltaire (third from left)

After the death of the Marquise in childbirth in September 1749, Voltaire briefly returned to Paris and in mid-1750 moved to Prussia at the invitation of Frederick the Great. The Prussian king (with the permission of Louis XV) made him a chamberlain in his household, appointed him to the Order of Merit, and gave him a salary of 20,000 French livres a year. He had rooms at Sanssouci and Charlottenburg Palace. Though life went well at first—in 1751 he completed Micromégas, a piece of science fiction involving ambassadors from another planet witnessing the follies of humankind—his relationship with Frederick the Great began to deteriorate after he was accused of theft and forgery by a Jewish financier, Abraham Hirschel, who had invested in Saxon government bonds, on behalf of Voltaire, at a time when Frederick was involved in sensitive diplomatic negotiations with Saxony.

He encountered other difficulties: an argument with Maupertuis, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science and a former rival for Émilie's affections, provoked Voltaire's Diatribe du docteur Akakia ("Diatribe of Doctor Akakia"), which satirized some of Maupertuis's theories and his abuse of power in his persecutions of a mutual acquaintance, Johann Samuel König. This greatly angered Frederick, who ordered all copies of the document burned. On 1 January 1752, Voltaire offered to resign as chamberlain and return his insignia of the Order of Merit; at first, Frederick refused until eventually permitting Voltaire to leave in March. On a slow journey back to France, Voltaire stayed at Leipzig and Gotha for a month each, and Kassel for two weeks, arriving at Frankfurt on 31 May. The following morning, he was detained at the inn where he was staying by Frederick's agents, who held him in the city for over three weeks while they, Voltaire and Frederick argued by letter over the return of a satirical book of poetry Frederick had lent to Voltaire. Marie Louise joined him on 9 June. She and her uncle only left Frankfurt in July after she had defended herself from the unwanted advances of one of Frederick's agents and Voltaire's luggage had been ransacked and valuable items taken.

Voltaire's attempts to vilify Frederick for his agents' actions at Frankfurt were largely unsuccessful. Voltaire responded by composing Mémoires pour Servir à la Vie de M. de Voltaire, a work published after his death that paints a largely negative picture of his time spent with Frederick. However, the correspondence between them continued, and though they never met in person again, after the Seven Years' War they largely reconciled.

Geneva and Ferney

Voltaire's slow progress toward Paris continued through Mainz, Mannheim, Strasbourg, and Colmar, but in January 1754 Louis XV banned him from Paris, so instead he turned for Geneva, near which he bought a large estate (Les Délices) in early 1755. Though he was received openly at first, the law in Geneva, which banned theatrical performances, and the publication of The Maid of Orleans against his will soured his relationship with Calvinist Genevans. In late 1758, he bought an even larger estate at Ferney, on the French side of the Franco-Swiss border.

Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism). This satire on Leibniz's philosophy of optimistic determinism remains the work for which Voltaire is perhaps best known. He would stay in Ferney for most of the remaining 20 years of his life, frequently entertaining distinguished guests, such as James Boswell, Adam Smith, Giacomo Casanova, and Edward Gibbon. In 1764, he published one of his best-known philosophical works, the Dictionnaire philosophique, a series of articles mainly on Christian history and dogmas, a few of which were originally written in Berlin.

From 1762, he began to champion unjustly persecuted people, the case of Huguenot merchant Jean Calas being the most celebrated. Calas had been tortured to death in 1763, supposedly because he had murdered his eldest son for wanting to convert to Catholicism. His possessions were confiscated and his two daughters were taken from his widow and were forced into Catholic convents. Voltaire, seeing this as a clear case of religious persecution, managed to overturn the conviction in 1765.

Voltaire was initiated into Freemasonry a little over a month before his death. On 4 April 1778, Voltaire attended la Loge des Neuf Sœurs in Paris, and became an Entered Apprentice Freemason. According to some sources, "Benjamin Franklin ... urged Voltaire to become a freemason; and Voltaire agreed, perhaps only to please Franklin." However, Benjamin Franklin was merely a visitor at the time Voltaire was initiated, the two only met a month before Voltaire's death, and their interactions with each other were brief.

Death and burial

In February 1778, Voltaire returned for the first time in over 25 years to Paris, among other reasons to see the opening of his latest tragedy, Irene. The five-day journey was too much for the 83-year-old, and he believed he was about to die on 28 February, writing "I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition." However, he recovered, and in March saw a performance of Irene, where he was treated by the audience as a returning hero.

House in Paris where Voltaire died

He soon became ill again and died on 30 May 1778. The accounts of his deathbed have been numerous and varying, and it has not been possible to establish the details of what precisely occurred. His enemies related that he repented and accepted the last rites given by a Catholic priest, or that he died under great torment, while his adherents told how he was defiant to his last breath. According to one story of his last words, his response to a priest at his deathbed urging him to renounce Satan was "Now is not the time for making new enemies." However, this appears to have originated from a joke first published in a Massachusetts newspaper in 1856, and was only attributed to Voltaire in the 1970s.

Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial in Paris, but friends and relations managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières in Champagne, where Marie Louise's brother was abbé. His heart and brain were embalmed separately.

Voltaire's tomb in the Paris Panthéon

Regarding Voltaire as a forerunner of the French Revolution, the National Assembly of France had his remains brought back to Paris, and enshrined in the Panthéon on 11 July 1791. It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry had composed especially for the event, which included a part for the "tuba curva" (an instrument that originated in Roman times as the cornu but had recently been revived under a new name).

Writings

History

Voltaire had an enormous influence on the development of historiography through his demonstration of fresh new ways to look at the past. Guillaume de Syon argues:Voltaire recast historiography in both factual and analytical terms. Not only did he reject traditional biographies and accounts that claim the work of supernatural forces, but he went so far as to suggest that earlier historiography was rife with falsified evidence and required new investigations at the source. Such an outlook was not unique in that the scientific spirit that 18th-century intellectuals perceived themselves as invested with. A rationalistic approach was key to rewriting history.Voltaire's best-known histories are History of Charles XII (1731), The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and his Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). He broke from the tradition of narrating diplomatic and military events, and emphasized customs, social history and achievements in the arts and sciences. The Essay on Customs traced the progress of world civilization in a universal context, thereby rejecting both nationalism and the traditional Christian frame of reference. Influenced by Bossuet's Discourse on the Universal History (1682), he was the first scholar to make a serious attempt to write the history of the world, eliminating theological frameworks, and emphasizing economics, culture and political history. He treated Europe as a whole, rather than a collection of nations. He was the first to emphasize the debt of medieval culture to Middle Eastern civilization, but otherwise was weak on the Middle Ages. Although he repeatedly warned against political bias on the part of the historian, he did not miss many opportunities to expose the intolerance and frauds of the church over the ages. Voltaire advised scholars that anything contradicting the normal course of nature was not to be believed. Although he found evil in the historical record, he fervently believed reason and educating the illiterate masses would lead to progress.

Voltaire explains his view of historiography in his article on "History" in Diderot's Encyclopédie: "One demands of modern historians more details, better ascertained facts, precise dates, more attention to customs, laws, mores, commerce, finance, agriculture, population." Voltaire's histories imposed the values of the Enlightenment on the past, but at the same time he helped free historiography from antiquarianism, Eurocentrism, religious intolerance and a concentration on great men, diplomacy, and warfare. Yale professor Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history", citing his "scrupulous concern for truths", "careful sifting of evidence", "intelligent selection of what is important", "keen sense of drama", and "grasp of the fact that a whole civilization is a unit of study".

Poetry

From an early age, Voltaire displayed a talent for writing verse and his first published work was poetry. He wrote two book-long epic poems, including the first ever written in French, the Henriade, and later, The Maid of Orleans, besides many other smaller pieces.The Henriade was written in imitation of Virgil, using the alexandrine couplet reformed and rendered monotonous for modern readers but it was a huge success in the 18th and early 19th century, with sixty-five editions and translations into several languages. The epic poem transformed French King Henry IV into a national hero for his attempts at instituting tolerance with his Edict of Nantes. La Pucelle, on the other hand, is a burlesque on the legend of Joan of Arc. Voltaire's minor poems are generally considered superior to either of these two works.

Prose

Frontispiece and first page of an early English translation by T. Smollett et al. of Voltaire's Candide, 1762

Many of Voltaire's prose works and romances, usually composed as pamphlets, were written as polemics. Candide attacks the passivity inspired by Leibniz's philosophy of optimism through the character Pangloss's frequent refrain that circumstances are the "best of all possible worlds". L'Homme aux quarante ecus (The Man of Forty Pieces of Silver), addresses social and political ways of the time; Zadig and others, the received forms of moral and metaphysical orthodoxy; and some were written to deride the Bible. In these works, Voltaire's ironic style, free of exaggeration, is apparent, particularly the restraint and simplicity of the verbal treatment. Candide in particular is the best example of his style. Voltaire also has—in common with Jonathan Swift—the distinction of paving the way for science fiction's philosophical irony, particularly in his Micromégas and the vignette Plato's Dream (1756).

In general, his criticism and miscellaneous writing show a similar style to Voltaire's other works. Almost all of his more substantive works, whether in verse or prose, are preceded by prefaces of one sort or another, which are models of his caustic yet conversational tone. In a vast variety of nondescript pamphlets and writings, he displays his skills at journalism. In pure literary criticism his principal work is the Commentaire sur Corneille, although he wrote many more similar works—sometimes (as in his Life and Notices of Molière) independently and sometimes as part of his Siècles.

Voltaire's works, especially his private letters, frequently contain the word "l'infâme" and the expression "écrasez l'infâme", or "crush the infamous". The phrase refers to abuses of the people by royalty and the clergy that Voltaire saw around him, and the superstition and intolerance that the clergy bred within the people. He had felt these effects in his own exiles, the burnings of his books and those of many others, and in the hideous sufferings of Jean Calas and François-Jean de la Barre. He stated in one of his most famous quotes that "Superstition sets the whole world in flames; philosophy quenches them."

The most oft-cited Voltaire quotation is apocryphal. He is incorrectly credited with writing, "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." These were not his words, but rather those of Evelyn Beatrice Hall, written under the pseudonym S. G. Tallentyre in her 1906 biographical book The Friends of Voltaire. Hall intended to summarize in her own words Voltaire's attitude towards Claude Adrien Helvétius and his controversial book De l'esprit, but her first-person expression was mistaken for an actual quotation from Voltaire. Her interpretation does capture the spirit of Voltaire's attitude towards Helvetius; it had been said Hall's summary was inspired by a quotation found in a 1770 Voltaire letter to an Abbot le Riche, in which he was reported to have said, "I detest what you write, but I would give my life to make it possible for you to continue to write." Nevertheless, scholars believe there must have again been misinterpretation, as the letter does not seem to contain any such quote.

Voltaire's first major philosophical work in his battle against "l'infâme" was the Traité sur la tolérance (Treatise on Tolerance), exposing the Calas affair, along with the tolerance exercised by other faiths and in other eras (for example, by the Jews, the Romans, the Greeks and the Chinese). Then, in his Dictionnaire philosophique, containing such articles as "Abraham", "Genesis", "Church Council", he wrote about what he perceived as the human origins of dogmas and beliefs, as well as inhuman behavior of religious and political institutions in shedding blood over the quarrels of competing sects. Amongst other targets, Voltaire criticized France's colonial policy in North America, dismissing the vast territory of New France as "a few acres of snow" ("quelques arpents de neige").

Letters

Voltaire also engaged in an enormous amount of private correspondence during his life, totalling over 20,000 letters. Theodore Besterman's collected edition of these letters, completed only in 1964, fills 102 volumes. One historian called the letters "a feast not only of wit and eloquence but of warm friendship, humane feeling, and incisive thought."In Voltaire's correspondence with Catherine the Great he derided democracy. He wrote, "Almost nothing great has ever been done in the world except by the genius and firmness of a single man combating the prejudices of the multitude."

Religious views

Voltaire at 70; engraving from 1843 edition of his Philosophical Dictionary

Like other key Enlightenment thinkers, Voltaire was a deist, expressing the idea: "What is faith? Is it to believe that which is evident? No. It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason." Voltaire held mixed views of the Abrahamic religions but had a favourable view of Hinduism.

In a 1763 essay, Voltaire supported the toleration of other religions and ethnicities: "It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?"

In one of his many denunciations of priests of every religious sect, Voltaire describes them as those who "rise from an incestuous bed, manufacture a hundred versions of God, then eat and drink God, then piss and shit God."

Christianity

In a letter to Frederick II, King of Prussia, dated 5 January 1767, he wrote about Christianity:La nôtre [religion] est sans contredit la plus ridicule, la plus absurde, et la plus sanguinaire qui ait jamais infecté le monde.

"Our [religion] is assuredly the most ridiculous, the most absurd and the most bloody religion which has ever infected this world. Your Majesty will do the human race an eternal service by extirpating this infamous superstition, I do not say among the rabble, who are not worthy of being enlightened and who are apt for every yoke; I say among honest people, among men who think, among those who wish to think. … My one regret in dying is that I cannot aid you in this noble enterprise, the finest and most respectable which the human mind can point out."In La bible enfin expliquée, he expressed the following attitude to lay reading of the Bible:

It is characteristic of fanatics who read the holy scriptures to tell themselves: God killed, so I must kill; Abraham lied, Jacob deceived, Rachel stole: so I must steal, deceive, lie. But, wretch, you are neither Rachel, nor Jacob, nor Abraham, nor God; you are just a mad fool, and the popes who forbade the reading of the Bible were extremely wise.Voltaire's opinion of the Christian Bible was mixed. Although influenced by Socinian works such as the Bibliotheca Fratrum Polonorum, Voltaire's skeptical attitude to the Bible separated him from Unitarian theologians like Fausto Sozzini or even Biblical-political writers like John Locke. His statements on religion also brought down on him the fury of the Jesuits and in particular Claude-Adrien Nonnotte. This did not hinder his religious practice, though it did win for him a bad reputation in certain religious circles. The deeply Christian Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote to his father the year of Voltaire's death, saying, "The arch-scoundrel Voltaire has finally kicked the bucket ...". Voltaire was later deemed to influence Edward Gibbon in claiming that Christianity was a contributor to the fall of the Roman Empire in his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

As Christianity advances, disasters befall the [Roman] empire—arts, science, literature, decay—barbarism and all its revolting concomitants are made to seem the consequences of its decisive triumph—and the unwary reader is conducted, with matchless dexterity, to the desired conclusion—the abominable Manicheism of Candide, and, in fact, of all the productions of Voltaire's historic school—viz., "that instead of being a merciful, ameliorating, and benignant visitation, the religion of Christians would rather seem to be a scourge sent on man by the author of all evil."However, Voltaire also acknowledged the self-sacrifice of Christians. He wrote: "Perhaps there is nothing greater on earth than the sacrifice of youth and beauty, often of high birth, made by the gentle sex in order to work in hospitals for the relief of human misery, the sight of which is so revolting to our delicacy. Peoples separated from the Roman religion have imitated but imperfectly so generous a charity." Yet "His hatred of religion increased with the passage of years. The attack, launched at first against clericalism and theocracy, ended in a furious assault upon Holy Scripture, the dogmas of the Church, and even upon the person of Jesus Christ Himself, who was depicted now as a degenerate". The reasoning of which may be summed up in his well-known quote, "Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities".

Judaism

According to Orthodox rabbi Joseph Telushkin, the most significant Enlightenment hostility against Judaism was found in Voltaire; thirty of the 118 articles in his Dictionnaire philosophique dealt with Jews and described them in consistently negative ways. For example, in Voltaire's A Philosophical Dictionary, he wrote of Jews: "In short, we find in them only an ignorant and barbarous people, who have long united the most sordid avarice with the most detestable superstition and the most invincible hatred for every people by whom they are tolerated and enriched."On the other hand, Peter Gay, a contemporary authority on the Enlightenment, also points to Voltaire's remarks (for instance, that the Jews were more tolerant than the Christians) in the Traité sur la tolérance and surmises that "Voltaire struck at the Jews to strike at Christianity". Whatever anti-semitism Voltaire may have felt, Gay suggests, derived from negative personal experience. Bertram Schwarzbach's far more detailed studies of Voltaire's dealings with Jewish people throughout his life concluded that he was anti-biblical, not anti-semitic. His remarks on the Jews and their "superstitions" were essentially no different from his remarks on Christians.

Telushkin states that Voltaire did not limit his attack to aspects of Judaism that Christianity used as a foundation, repeatedly making it clear that he despised Jews. Arthur Hertzberg claims that Gay's second suggestion is also untenable, as Voltaire himself denied its validity when he remarked that he had "forgotten about much larger bankruptcies through Christians".

Some authors link Voltaire's anti-Judaism to his polygenism. According to Joxe Azurmendi this anti-Judaism has a relative importance in Voltaire's philosophy of history. However, Voltaire's anti-Judaism influences later authors like Ernest Renan.

According to the historian Will Durant, Voltaire had initially condemned the persecution of Jews on several occasions including in his work Henriade. As stated by Durant, Voltaire had praised the simplicity, sobriety, regularity, and industry of Jews. However, subsequently, Voltaire had become strongly anti-Semitic after some regrettable personal financial transactions and quarrels with Jewish financiers. In his Essai sur les moeurs Voltaire had denounced the ancient Hebrews using strong language; a Catholic priest had protested against this censure. The anti-Semitic passages in Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique were criticized by Issac Pinto in 1762. Subsequently, Voltaire agreed with the criticism of his anti-Semitic views and stated that he had been "wrong to attribute to a whole nation the vices of some individuals"; he also promised to revise the objectionable passages for forthcoming editions of the Dictionnaire philosophique, but failed to do so.

Islam

Voltaire's views about Islam remained negative as he considered the Qur'an to be ignorant of the laws of physics. In a 1740 letter to Frederick II of Prussia, Voltaire ascribes to Muhammad a brutality that "is assuredly nothing any man can excuse" and suggests that his following stemmed from superstition and lack of enlightenment. Voltaire continued in his letter, "But that a camel-merchant should stir up insurrection in his village; that in league with some miserable followers he persuades them that he talks with the angel Gabriel; that he boasts of having been carried to heaven, where he received in part this unintelligible book, each page of which makes common sense shudder; that, to pay homage to this book, he delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse, at least if he was not born a Turk, or if superstition has not extinguished all natural light in him." – Referring to Muhammad, in a letter to Frederick II of Prussia (December 1740), published in Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Vol. 7 (1869), edited by Georges Avenel, p. 105.In 1748, after having read Henri de Boulainvilliers and George Sale, he wrote again about Mohammed and Islam in an article, "De l'Alcoran et de Mahomet" (On the Quran and on Mohammed). In the article, Voltaire maintained that Mohammed was a "sublime charlatan" Drawing also on complementary information in the "Oriental Library" of Herbelot, Voltaire, according to René Pomeau, had a judgement of the Qur'an where he found the book in spite of "the contradictions, the absurdities, the anachronisms", "rhapsody, without connection, without order, and without art". Thus he "henceforward conceded" that "if his book was bad for our times and for us, it was very good for his contemporaries, and his religion even more so. It must be admitted that he removed almost all of Asia from idolatry" and that "it was difficult for such a simple and wise religion, taught by a man who was constantly victorious, could hardly fail to subjugate a portion of the earth." He considered that "its civil laws are good; its dogma is admirable which it has in common with ours" but that "his means are shocking; deception and murder".

Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations

Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations (French: Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations) is a work of Voltaire, published for the first time in its entirety in 1756. In this work, Voltaire deals with the history of Europe before Charlemagne to the dawn of the age of Louis XIV, also evoking that of the colonies and the East. As a historian he devoted several chapters to Islam, Voltaire highlighted the Arabian, Turkish courts, and conducts. Here he called Mohammed a "poet", and furthermore he was not an illiterate. As a "legislator" who "changed the face of part of Europe, one half of Asia", In the chapter VI, Voltaire finds similarities between Arabs and ancient Hebrews, that they both kept running to battle in the name of god, and sharing the passion for booty and spoils. Voltaire continues that, "It is to be believed that Mohammed, like all enthusiasts, violently struck by his ideas, first presented them in good faith, strengthened them with fantasy, fooled himself in fooling others, and supported through necessary deceptions a doctrine which he considered good." He thus compares "the genius of the Arab people" with "the genius of the ancient Romans".Drama Mahomet

The tragedy Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet (French: Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophete) was written in 1736 by Voltaire. The play is a study of religious fanaticism and self-serving manipulation. The character Muhammad orders the murder of his critics. Voltaire described the play as "written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect".Voltaire described Muhammad as an "impostor", a " false prophet", a "fanatic" and a "hypocrite". Defending the play, Voltaire said that he "tried to show in it into what horrible excesses fanaticism, led by an impostor, can plunge weak minds".

When Voltaire wrote in 1742 to César de Missy, he described Mohammed as a "deceitful character."

In his play, Mohammed was "whatever trickery can invent that is most atrocious and whatever fanaticism can accomplish that is most horrifying. Mahomet here is nothing other than Tartuffe with armies at his command." After later having judged that he had made Mohammed in his play "somewhat nastier than he really was", Voltaire claims that Muhammad stole the idea of an angel weighing both men and women from Zoroastrians, who are often referred to as "Magi". Voltaire continues about Islam, saying:

"Nothing is more terrible than a people who, having nothing to lose, fight in the united spirit of rapine and of religion."In a 1745 letter recommending the play to Pope Benedict XIV, Voltaire described Muhammad as "the founder of a false and barbarous sect" and "a false prophet." Voltaire wrote: "Your holiness will pardon the liberty taken by one of the lowest of the faithful, though a zealous admirer of virtue, of submitting to the head of the true religion this performance, written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect. To whom could I with more propriety inscribe a satire on the cruelty and errors of a false prophet, than to the vicar and representative of a God of truth and mercy?". His view was modified slightly for Essai sur les Moeurs et l'Esprit des Nations, although they remained negative. In 1751, Voltaire performed his play Mohamet once again, with great success.

Hinduism

Commenting on the sacred texts of the Hindus, the Vedas, Voltaire observed:The Veda was the most precious gift for which the West had ever been indebted to the East.He regarded Hindus as "[a] peaceful and innocent people, equally incapable of hurting others or of defending themselves". Voltaire was himself a supporter of animal rights and was a vegetarian. He used the antiquity of Hinduism to land what he saw as a devastating blow to the Bible's claims and acknowledged that the Hindus' treatment of animals showed a shaming alternative to the immorality of European imperialists.

Views on race and slavery

Voltaire rejected the biblical Adam and Eve story and was a polygenist who speculated that each race had entirely separate origins. According to William Cohen, like most other polygenists, Voltaire believed that because of their different origins blacks did not entirely share the natural humanity of whites. According to David Allen Harvey, Voltaire often invoked racial differences as a means to attack religious orthodoxy, and the Biblical account of creation.His most famous remark on slavery is found in Candide, where the hero is horrified to learn "at what price we eat sugar in Europe" after coming across a slave in French Guiana who has been mutilated for escaping, who opines that, if all human beings have common origins as the Bible taught, it makes them cousins, concluding that "no one could treat their relatives more horribly". Elsewhere, he wrote caustically about "whites and Christians [who] proceed to purchase negroes cheaply, in order to sell them dear in America". Voltaire has been accused of supporting the slave trade as per a letter attributed to him, although it has been suggested that this letter is a forgery "since no satisfying source attests to the letter's existence."

In his Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire endorses Montesquieu's criticism of the slave trade: "Montesquieu was almost always in error with the learned, because he was not learned, but he was almost always right against the fanatics and the promoters of slavery."

Zeev Sternhell argues that despite his shortcomings, Voltaire was a forerunner of liberal pluralism in his approach to history and non-European cultures. Voltaire wrote, "We have slandered the Chinese because their metaphysics is not the same as ours ... This great misunderstanding about Chinese rituals has come about because we have judged their usages by ours, for we carry the prejudices of our contentious spirit to the end of the world." In speaking of Persia, he condemned Europe's "ignorant audacity" and "ignorant credulity". When writing about India, he declares, "It is time for us to give up the shameful habit of slandering all sects and insulting all nations!" In Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations, he defended the integrity of the Native Americans and wrote favorably of the Inca Empire.

Appreciation and influence

According to Victor Hugo: "To name Voltaire is to characterize the entire eighteenth century." Goethe regarded Voltaire to be the greatest literary figure in modern times, and possibly of all times. According to Diderot, Voltaire's influence on posterity would extend far into the future.Napoleon commented that till he was sixteen he "would have fought for Rousseau against the friends of Voltaire, today it is the opposite...The more I read Voltaire the more I love him. He is a man always reasonable, never a charlatan, never a fanatic." Frederick the Great commented on his good fortune for having lived in the age of Voltaire, and corresponded with him throughout his reign until Voltaire's death.

In England, Voltaire's views influenced Godwin, Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Bentham, Byron and Shelley. Macaulay made note of the fear that Voltaire's very name incited in tyrants and fanatics.

In Russia, Catherine the Great had been reading Voltaire for sixteen years prior to becoming Empress in 1762. In October 1763, she began a correspondence with the philosopher that continued till his death. The content of these letters has been described as being akin to a student writing to a teacher. Upon Voltaire's death, the Empress purchased his library, which was then transported and placed in The Hermitage. Alexander Herzen remarked that "The writings of the egoist Voltaire did more for liberation than those of the loving Rousseau did for brotherhood." In his famous Letter to Gogol, Vissarion Belinsky wrote that Voltaire "stamped out the fires of fanaticism and ignorance in Europe by ridicule".

In his native Paris, Voltaire was viewed as the defender of Jean Calas and Pierre Sirven. Although he failed in securing the annulment of la Barre's execution for "blasphemies" against Christianity, despite a protracted campaign, the criminal code that sanctioned the execution was revised during Voltaire's lifetime. In 1764, Voltaire successfully intervened and secured the release of Claude Chamont for the crime of attending Protestant services. When Comte de Lally was executed for treason in 1766, Voltaire wrote a 300-page document absolving de Lally. Subsequently, in 1778, the judgment against de Lally was expunged just before Voltaire's death. The Genevan Protestant minister Pomaret once said to Voltaire, "You seem to attack Christianity, and yet you do the work of a Christian." Frederick the Great noted the significance of a philosopher capable of influencing judges to change their unjust decisions, commenting that this alone is sufficient to ensure the prominence of Voltaire as a humanitarian.

Under the French Third Republic, anarchists and socialists often invoked Voltaire's writings in their struggles against militarism, nationalism, and the Catholic Church. The section condemning the futility and imbecility of war in the Dictionnaire philosophique was a frequent favorite, as were his arguments that nations can only grow at the expense of others. Following the liberation of France from the Vichy regime in 1944, Voltaire's 250th birthday was celebrated in both France and the Soviet Union, honoring him as "one of the most feared opponents" of the Nazi collaborators and someone "whose name symbolizes freedom of thought, and hatred of prejudice, superstition, and injustice."

Jorge Luis Borges stated that "not to admire Voltaire is one of the many forms of stupidity" and included his short fiction such as Micromégas in "The Library of Babel" and "A Personal Library." Gustave Flaubert believed that France had erred gravely by not following the path forged by Voltaire instead of Rousseau.

Most architects of modern America were adherents of Voltaire's views. According to Will Durant:

Italy had a Renaissance, and Germany had a Reformation, but France had Voltaire; he was for his country both Renaissance and Reformation, and half the Revolution. He was first and best in his time in his conception and writing of history, in the grace of his poetry, in the charm and wit of his prose, in the range of his thought and his influence. His spirit moved like a flame over the continent and the century, and stirs a million souls in every generation.

Voltaire and Rousseau

Voltaire's junior contemporary Jean Jacques Rousseau commented on how Voltaire's book Letters on the English played a great role in his intellectual development. Having written some literary works and also some music, in December 1745 Rousseau wrote a letter introducing himself to Voltaire, who was by then the most prominent literary figure in France, to which Voltaire replied with a polite response. Subsequently, when Rousseau sent Voltaire a copy of his book Discourse on Inequality, Voltaire replied, noting his disagreement with the views expressed in the book:No one has ever employed so much intellect to persuade men to be beasts. In reading your work one is seized with a desire to walk on four paws [marcher à quatre pattes]. However, as it is more than sixty years since I lost that habit, I feel, unfortunately, that it is impossible for me to resume it.Subsequently, commenting on Rousseau's romantic novel Julie, or the New Heloise, Voltaire stated:

No more about Jean-Jacques' romance if you please. I have read it, to my sorrow, and it would be to his if I had time to say what I think of this silly book.Voltaire speculated that the first half of Julie had been written in a brothel and the second half in a lunatic asylum. In his Lettres sur La Nouvelle Heloise, written under a pseudonym, Voltaire offered criticism highlighting grammatical mistakes in the book:

Paris recognized Voltaire's hand and judged the patriarch to be bitten by jealousy.In reviewing Rousseau's book Emile after its publication, Voltaire dismissed it as "a hodgepodge of a silly wet nurse in four volumes, with forty pages against Christianity, among the boldest ever known." However, he expressed admiration for the section in this book titled Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar, calling it "fifty good pages...it is regrettable that they should have been written by...such a knave." He went on to predict that Emile would be forgotten after a month.

In 1764, Rousseau published Lettres de la montagne, containing nine letters on religion and politics. In the fifth letter he wondered why Voltaire had not been able to imbue the Genevan councilors, who frequently met him, "with that spirit of tolerance which he preaches without cease, and of which he sometimes has need". The letter continued with an imaginary speech delivered by Voltaire, imitating his literary style, in which he accepts authorship for the book Sermon of the Fifty—a book whose authorship Voltaire had repeatedly denied because it contained many heresies.

In 1772, when a priest sent Rousseau a pamphlet denouncing Voltaire, Rousseau responded with a defense of Voltaire:

He has said and done so many good things that we should draw the curtain over his irregularities.In 1778, when Voltaire was given unprecedented honors at the Théâtre-Français, an acquaintance of Rousseau ridiculed the event. This was met by a sharp retort from Rousseau:

How dare you mock the honors rendered to Voltaire in the temple of which he is the god, and by the priests who for fifty years have been living off his masterpieces?On 2 July 1778, Rousseau died one month after Voltaire's death. In October 1794, Rousseau's remains were moved to the Panthéon, where they were placed near the remains of Voltaire.

Louis XVI, while incarcerated in the Temple, had remarked that Rousseau and Voltaire had "destroyed France", by which he meant his dynasty.

Legacy

Voltaire, by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1778 (National Gallery of Art)

Voltaire perceived the French bourgeoisie to be too small and ineffective, the aristocracy to be parasitic and corrupt, the commoners as ignorant and superstitious, and the Church as a static and oppressive force useful only on occasion as a counterbalance to the rapacity of kings, although all too often, even more rapacious itself. Voltaire distrusted democracy, which he saw as propagating the idiocy of the masses. Voltaire long thought only an enlightened monarch could bring about change, given the social structures of the time and the extremely high rates of illiteracy, and that it was in the king's rational interest to improve the education and welfare of his subjects. But his disappointments and disillusions with Frederick the Great changed his philosophy somewhat, and soon gave birth to one of his most enduring works, his novella Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism, 1759), which ends with a new conclusion: "It is up to us to cultivate our garden." His most polemical and ferocious attacks on intolerance and religious persecutions indeed began to appear a few years later. Candide was also burned and Voltaire jokingly claimed the actual author was a certain 'Demad' in a letter, where he reaffirmed the main polemical stances of the text.

He is remembered and honoured in France as a courageous polemicist who indefatigably fought for civil rights (as the right to a fair trial and freedom of religion) and who denounced the hypocrisies and injustices of the Ancien Régime. The Ancien Régime involved an unfair balance of power and taxes between the three Estates: clergy and nobles on one side, the commoners and middle class, who were burdened with most of the taxes, on the other. He particularly had admiration for the ethics and government as exemplified by the Chinese philosopher Confucius.

Voltaire is also known for many memorable aphorisms, such as "Si Dieu n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer" ("If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him"), contained in a verse epistle from 1768, addressed to the anonymous author of a controversial work on The Three Impostors. But far from being the cynical remark it is often taken for, it was meant as a retort to atheistic opponents such as d'Holbach, Grimm, and others. He has had his detractors among his later colleagues. The Scottish Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle argued that "Voltaire read history, not with the eye of devout seer or even critic, but through a pair of mere anti-catholic spectacles."

The town of Ferney, where Voltaire lived out the last 20 years of his life, was officially named Ferney-Voltaire in honour of its most famous resident in 1878. His château is a museum. Voltaire's library is preserved intact in the National Library of Russia at Saint Petersburg, Russia. In the Zurich of 1916, the theatre and performance group who would become the early avant-garde movement Dada named their theater The Cabaret Voltaire. A late-20th-century industrial music group then named themselves after the theater. Astronomers have bestowed his name to the Voltaire crater on Deimos and the asteroid 5676 Voltaire.

Voltaire was also known to have been an advocate for coffee, as he was reported to have drunk it 50–72 times per day. It has been suggested that high amounts of caffeine acted as a mental stimulant to his creativity. His great-grand-niece was the mother of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Catholic philosopher and Jesuit priest. His book Candide was listed as one of The 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written, by Martin Seymour-Smith.

In the 1950s, the bibliographer and translator Theodore Besterman started to collect, transcribe and publish all of Voltaire's writings. He founded the Voltaire Institute and Museum in Geneva where he began publishing collected volumes of Voltaire's correspondence. On his death in 1976, he left his collection to the University of Oxford, where the Voltaire Foundation became established as a department. The Foundation has continued to publish the Complete Works of Voltaire, a complete chronological series which is expected to reach completion in 2018, reaching around 200 volumes, fifty years after the series began. It also publishes the series Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment, begun by Bestermann as Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, which has reached more than 500 volumes.

Chronology

Works

Philosophical and political treatises, essays and letters

- Letters on the Quakers (1727)

- Letters concerning the English nation (London, 1733) (French version entitled Lettres philosophiques sur les Anglais, Rouen, 1734), revised as Letters on the English (circa 1778)

- Le Mondain (1736)

- Sept Discours en Vers sur l'Homme (1738)

- The Elements of Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophy (1738; 2nd expanded ed. 1745)

- Dictionnaire philosophique (1752)

- The Sermon of the Fifty (1759)

- The Calas Affair: A Treatise on Tolerance (1762)

- Traité sur la tolérance (1763)

- Ce qui plaît aux dames (1764)

- Idées républicaines (1765)

- La Philosophie de l'histoire (1765)

- Questions sur les Miracles (1765)

- L'Ingénu (1767)

- La Princesse de Babylone (1768)

- Des singularités de la nature (1768)

Novellas

- The One-eyed Street Porter, Cosi-sancta (1715)

- Plato's Dream (1737)

- Micromegas (1738)

- The World as it Goes (1750)

- Memnon (1750)

- Bababec and the Fakirs (1750)

- Timon (1755)

- The Travels of Scarmentado (1756)

- The Two Consoled Ones (1756)

- Zadig, or, Destiny (1757)

- Candide, or Optimism (1758)

- Story of a Good Brahman (1759)

- The King of Boutan (1761)

- The City of Cashmere (1760)

- An Indian Adventure (1764)

- The White and the Black (1764)

- Jeannot and Colin (1764)

- The Blind Judges of Colors (1766)

- The Princess of Babylon (1768)

- The Man with Forty Crowns (1768)

- The Letters of Amabed (1769)

- The Huron, or Pupil of Nature (1771)

- The White Bull (1772)

- An Incident of Memory (1773)

- The History of Jenni (1774)

- The Travels of Reason (1774)

- The Ears of Lord Chesterfield and Chaplain Goudman (1775)

Plays

Voltaire wrote between fifty and sixty plays, including a few unfinished ones. Among them are:- Œdipe (1718)

- Mariamne (1724)

- Éryphile (1732)

- Zaïre (1732)

- Mahomet (1741)

- Mérope (1743)

- La princesse de Navarre (1745)

- Nanine (1749)

- L'Orphelin de la Chine (1755)

- Socrate (published 1759)

- La Femme qui a Raison (1759)

- Irène (1778)

- Agathocle (1779)

History

- History of Charles XII, King of Sweden (1731)

- The Age of Louis XIV (1751)

- The Age of Louis XV (1746–1752; published separately 1768)

- Annals of the Empire – Charlemagne, AD 742 – Henry VII 1313, Vol. I (1754)

- Annals of the Empire – Louis of Bavaria, 1315 to Ferdinand II 1631 Vol. II (1754)

- Essay on Universal History, the Manners, and Spirit of Nations (1756)

- History of the Russian Empire Under Peter the Great (Vol. I 1759; Vol. II 1763)

Critical editions

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, A. Beuchot (ed.). 72 vols. (1829–40)

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Louis E.D. Moland and G. Bengesco (eds.}. 52 vols. (1877–85)

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Theodore Besterman, et al. (eds.). 144 vols. (1968–<2018>)