Methamphetamine (contracted from N-methylamphetamine) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is mainly used as a recreational drug and less commonly as a second-line treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obesity. Methamphetamine was discovered in 1893 and exists as two enantiomers: levo-methamphetamine and dextro-methamphetamine. Methamphetamine properly refers to a specific chemical, the racemic free base (while INN name metamfetamine refers to single enantiomer, dextromethamphetamine), which is an equal mixture of levomethamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine in their pure amine forms. It is rarely prescribed over concerns involving human neurotoxicity and potential for recreational use as an aphrodisiac and euphoriant, among other concerns, as well as the availability of safer substitute drugs with comparable treatment efficacy. Dextromethamphetamine is a much stronger CNS stimulant than levomethamphetamine.

Both methamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine are illicitly trafficked and sold owing to their potential for recreational use. The highest prevalence of illegal methamphetamine use occurs in parts of Asia, Oceania, and in the United States, where racemic methamphetamine, levomethamphetamine, and dextromethamphetamine are classified as schedule II controlled substances.

Levomethamphetamine is available as an over-the-counter (OTC) drug for use as an inhaled nasal decongestant in the United States. Internationally, the production, distribution, sale, and possession of methamphetamine is restricted or banned in many countries, due to its placement in schedule II of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances treaty. While dextromethamphetamine is a more potent drug, racemic methamphetamine is sometimes illicitly produced due to the relative ease of synthesis and limited availability of chemical precursors.

In low to moderate doses, methamphetamine can elevate mood, increase alertness, concentration and energy in fatigued individuals, reduce appetite, and promote weight loss. At relatively high doses, it can induce psychosis, breakdown of skeletal muscle, seizures and bleeding in the brain. Chronic high-dose use can precipitate unpredictable and rapid mood swings, stimulant psychosis (e.g., paranoia, hallucinations, delirium, and delusions) and violent behavior. Recreationally, methamphetamine's ability to increase energy has been reported to lift mood and increase sexual desire to such an extent that users are able to engage in sexual activity continuously for several days. Methamphetamine is known to possess a high addiction liability (i.e., a high likelihood that long-term or high dose use will lead to compulsive drug use) and high dependence liability (i.e. a high likelihood that withdrawal symptoms will occur when methamphetamine use ceases). Heavy recreational use of methamphetamine may lead to a post-acute-withdrawal syndrome, which can persist for months beyond the typical withdrawal period. Unlike amphetamine, methamphetamine is neurotoxic to human midbrain dopaminergic neurons. It has also been shown to damage serotonin neurons in the CNS. This damage includes adverse changes in brain structure and function, such as reductions in grey matter volume in several brain regions and adverse changes in markers of metabolic integrity.

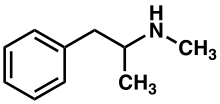

Methamphetamine belongs to the substituted phenethylamine and substituted amphetamine chemical classes. It is related to the other dimethylphenethylamines as a positional isomer of these compounds, which share the common chemical formula: C10H15N1.

Uses

Medical

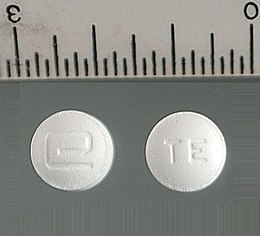

In the United States, dextromethamphetamine hydrochloride, under the trade name Desoxyn, has been approved by the FDA for treating ADHD and obesity in both adults and children; however, the FDA also indicates that the limited therapeutic usefulness of methamphetamine should be weighed against the inherent risks associated with its use. Methamphetamine is sometimes prescribed off label for narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia. In the United States, methamphetamine's levorotary form is available in some over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant products.As methamphetamine is associated with a high potential for misuse, the drug is regulated under the Controlled Substances Act and is listed under Schedule II in the United States. Methamphetamine hydrochloride dispensed in the United States is required to include a boxed warning regarding its potential for recreational misuse and addiction liability.

Recreational

Methamphetamine is often used recreationally for its effects as a potent euphoriant and stimulant as well as aphrodisiac qualities.

According to a National Geographic TV documentary on methamphetamine, an entire subculture known as party and play is based around sexual activity and methamphetamine use.

Participants in this subculture, which consists almost entirely of

homosexual male methamphetamine users, will typically meet up through internet dating sites and have sex. Due to its strong stimulant and aphrodisiac effects and inhibitory effect on ejaculation, with repeated use, these sexual encounters will sometimes occur continuously for several days on end. The crash following the use of methamphetamine in this manner is very often severe, with marked hypersomnia (excessive daytime sleepiness). The party and play subculture is prevalent in major US cities such as San Francisco and New York City.

Contraindications

Methamphetamine is contraindicated in individuals with a history of substance use disorder, heart disease, or severe agitation or anxiety, or in individuals currently experiencing arteriosclerosis, glaucoma, hyperthyroidism, or severe hypertension. The FDA states that individuals who have experienced hypersensitivity reactions to other stimulants in the past or are currently taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors should not take methamphetamine. The FDA also advises individuals with bipolar disorder, depression, elevated blood pressure, liver or kidney problems, mania, psychosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, seizures, thyroid problems, tics, or Tourette syndrome to monitor their symptoms while taking methamphetamine. Due to the potential for stunted growth, the FDA advises monitoring the height and weight of growing children and adolescents during treatment.Side effects

Physical

The physical effects of methamphetamine can include loss of appetite, hyperactivity, dilated pupils, flushed skin, excessive sweating, increased movement, dry mouth and teeth grinding (leading to "meth mouth"), headache, irregular heartbeat (usually as accelerated heartbeat or slowed heartbeat), rapid breathing, high blood pressure, low blood pressure, high body temperature, diarrhea, constipation, blurred vision, dizziness, twitching, numbness, tremors, dry skin, acne, and pale appearance.Meth mouth

A suspected case of meth mouth

Methamphetamine users and addicts may lose their teeth abnormally quickly, regardless of the route of administration, from a condition informally known as meth mouth. The condition is generally most severe in users who inject the drug, rather than swallow, smoke, or inhale it. According to the American Dental Association, meth mouth "is probably caused by a combination of drug-induced psychological and physiological changes resulting in xerostomia (dry mouth), extended periods of poor oral hygiene, frequent consumption of high-calorie, carbonated beverages and bruxism (teeth grinding and clenching)". As dry mouth is also a common side effect of other stimulants, which are not known to contribute severe tooth decay, many researchers suggest that methamphetamine associated tooth decay is more due to users' other choices. They suggest the side effect has been exaggerated and stylized to create a stereotype of current users as a deterrence for new ones.

Sexually transmitted infection

Methamphetamine use was found to be related to higher frequencies of unprotected sexual intercourse in both HIV-positive and unknown casual partners, an association more pronounced in HIV-positive participants. These findings suggest that methamphetamine use and engagement in unprotected anal intercourse are co-occurring risk behaviors, behaviors that potentially heighten the risk of HIV transmission among gay and bisexual men. Methamphetamine use allows users of both sexes to engage in prolonged sexual activity, which may cause genital sores and abrasions as well as priapism in men. Methamphetamine may also cause sores and abrasions in the mouth via bruxism, increasing the risk of sexually transmitted infection.Besides the sexual transmission of HIV, it may also be transmitted between users who share a common needle. The level of needle sharing among methamphetamine users is similar to that among other drug injection users.

Psychological

The psychological effects of methamphetamine can include euphoria, dysphoria, changes in libido, alertness, apprehension and concentration, decreased sense of fatigue, insomnia or wakefulness, self-confidence, sociability, irritability, restlessness, grandiosity and repetitive and obsessive behaviors. Peculiar to methamphetamine and related stimulants is "punding", persistent non-goal-directed repetitive activity. Methamphetamine use also has a high association with anxiety, depression, amphetamine psychosis, suicide, and violent behaviors.Neurotoxicity and neuroimmune response

This diagram depicts the neuroimmune mechanisms that mediate methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration in the human brain. The NF-κB-mediated neuroimmune response to methamphetamine use which results in the increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier arises through its binding at and activation of sigma receptors, the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), the dysregulation of glutamate transporters (specifically, EAAT1 and EAAT2) and glucose metabolism, and excessive Ca2+ ion influx in glial cells and dopamine neurons.

Magnetic resonance imaging studies on human methamphetamine users have also found evidence of neurodegeneration, or adverse neuroplastic changes in brain structure and function. In particular, methamphetamine appears to cause hyperintensity and hypertrophy of white matter, marked shrinkage of hippocampi, and reduced gray matter in the cingulate cortex, limbic cortex, and paralimbic cortex in recreational methamphetamine users. Moreover, evidence suggests that adverse changes in the level of biomarkers of metabolic integrity and synthesis occur in recreational users, such as a reduction in N-acetylaspartate and creatine levels and elevated levels of choline and myoinositol.

Methamphetamine has been shown to activate TAAR1 in human astrocytes and generate cAMP as a result. Activation of astrocyte-localized TAAR1 appears to function as a mechanism by which methamphetamine attenuates membrane-bound EAAT2 (SLC1A2) levels and function in these cells.

Methamphetamine binds to and activates both sigma receptor subtypes, σ1 and σ2, in the brain. Sigma receptor activation by methamphetamine promotes methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity by facilitating hyperthermia, increasing dopamine synthesis and release, influencing microglial activation, and modulating apoptotic signaling cascades and the formation of reactive oxygen species.

A 2015 review concluded that the behaviour resulting from the use of methamphetamine is likely caused in part from the neurotoxic effects of the drug. Excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, metabolic compromise, UPS dysfunction, protein nitration, endoplasmic reticulum stress, p53 expression and other processes contributed to this neurotoxicity.

Overdose

A methamphetamine overdose may result in a wide range of symptoms. A moderate overdose of methamphetamine may induce symptoms such as: abnormal heart rhythm, confusion, difficult and/or painful urination, high or low blood pressure, high body temperature, over-active and/or over-responsive reflexes, muscle aches, severe agitation, rapid breathing, tremor, urinary hesitancy, and an inability to pass urine. An extremely large overdose may produce symptoms such as adrenergic storm, methamphetamine psychosis, substantially reduced or no urine output, cardiogenic shock, bleeding in the brain, circulatory collapse, hyperpyrexia (i.e., dangerously high body temperature), pulmonary hypertension, kidney failure, rapid muscle breakdown, serotonin syndrome, and a form of stereotypy ("tweaking"). A methamphetamine overdose will likely also result in mild brain damage due to dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotoxicity. Death from methamphetamine poisoning is typically preceded by convulsions and coma.Psychosis

Abuse of methamphetamine can result in a stimulant psychosis which may present with a variety of symptoms (e.g., paranoia, hallucinations, delirium, and delusions). A Cochrane Collaboration review on treatment for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine abuse-induced psychosis states that about 5–15% of users fail to recover completely. The same review asserts that, based upon at least one trial, antipsychotic medications effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis. Amphetamine psychosis may also develop occasionally as a treatment-emergent side effect.Emergency treatment

Acute methamphetamine intoxication is largely managed by treating the symptoms and treatments may initially include administration of activated charcoal and sedation. There is not enough evidence on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis in cases of methamphetamine intoxication to determine their usefulness. Forced acid diuresis (e.g., with vitamin C) will increase methamphetamine excretion but is not recommended as it may increase the risk of aggravating acidosis, or cause seizures or rhabdomyolysis. Hypertension presents a risk for intracranial hemorrhage (i.e., bleeding in the brain) and, if severe, is typically treated with intravenous phentolamine or nitroprusside. Blood pressure often drops gradually following sufficient sedation with a benzodiazepine and providing a calming environment.Antipsychotics such as haloperidol are useful in treating agitation and psychosis from methamphetamine overdose. Beta blockers with lipophilic properties and CNS penetration such as metoprolol and labetalol may be useful for treating CNS and cardiovascular toxicity. The mixed alpha- and beta-blocker labetalol is especially useful for treatment of concomitant tachycardia and hypertension induced by methamphetamine. The phenomenon of "unopposed alpha stimulation" has not been reported with the use of beta-blockers for treatment of methamphetamine toxicity.

Addiction

Current models of addiction from chronic drug use involve alterations in gene expression in certain parts of the brain, particularly the nucleus accumbens. The most important transcription factors that produce these alterations are ΔFosB, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB). ΔFosB plays a crucial role in the development of drug addictions, since its overexpression in D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for most of the behavioral and neural adaptations that arise from addiction. Once ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it induces an addictive state that becomes increasingly more severe with further increases in ΔFosB expression. It has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, propofol, and substituted amphetamines, among others.ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase enzyme, both directly oppose the induction of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens (i.e., they oppose increases in its expression). Sufficiently overexpressing ΔJunD in the nucleus accumbens with viral vectors can completely block many of the neural and behavioral alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB). ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise. Since both natural rewards and addictive drugs induce expression of ΔFosB (i.e., they cause the brain to produce more of it), chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological state of addiction. ΔFosB is the most significant factor involved in both amphetamine addiction and amphetamine-induced sex addictions, which are compulsive sexual behaviors that result from excessive sexual activity and amphetamine use. These sex addictions (i.e., drug-induced compulsive sexual behaviors) are associated with a dopamine dysregulation syndrome which occurs in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs, such as amphetamine or methamphetamine.

Epigenetic factors in methamphetamine addiction

Methamphetamine addiction is persistent for many individuals, with 61% of individuals treated for addiction relapsing within one year. About half of those with methamphetamine addiction continue with use over a ten-year period, while the other half reduce use starting at about one to four years after initial use.The frequent persistence of addiction suggests that long-lasting changes in gene expression may occur in particular regions of the brain, and may contribute importantly to the addiction phenotype. Recently a crucial role has been found for epigenetic mechanisms in driving lasting changes in gene expression in the brain.

A review in 2015 summarized a number of studies involving chronic methamphetamine use in rodents. Epigenetic alterations were observed in the brain "reward" regions, including the ventral tegmental area, the nucleus accumbens, the dorsal striatum, the hippocampus, and the prefrontal cortex. Chronic methamphetamine use caused gene-specific histone acetylations, deacetylations and methylations. Gene-specific DNA methylations in particular regions of the brain were also observed. The various epigenetic alterations caused downregulations or upregulations of specific genes important in addiction. For instance, chronic methamphetamine use caused methylation of the lysine in position 4 of histone 3 located at the promoters of the c-fos and the C-C chemokine receptor 2 (ccr2) genes, activating those genes in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). c-fos is well known to be important in addiction. The ccr2 gene is also important in addiction, since mutational inactivation of this gene impairs addiction.

In methamphetamine addicted rats, epigenetic regulation through reduced acetylation of histones, in brain striatal neurons, caused reduced transcription of glutamate receptors. Glutamate receptors play an important role in regulating the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse.

Treatment and management

Cognitive behavioral therapy is currently the most effective clinical treatment for psychostimulant addictions in general. As of May 2014, there is no effective pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine addiction. Methamphetamine addiction is largely mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Magnesium ions inhibit NMDA receptors by blocking the receptor calcium channel.Dependence and withdrawal

Tolerance is expected to develop with regular methamphetamine use and, when used recreationally, this tolerance develops rapidly. In dependent users, withdrawal symptoms are positively correlated with the level of drug tolerance. Depression from methamphetamine withdrawal lasts longer and is more severe than that of cocaine withdrawal.According to the current Cochrane review on drug dependence and withdrawal in recreational users of methamphetamine, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue [methamphetamine] use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose". Withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in up to 87.6% of cases, and persist for three to four weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week. Methamphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, dysphoric mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and vivid or lucid dreams.

Methamphetamine that is present in a mother's bloodstream can pass through the placenta to a fetus and be secreted into breast milk. Infants born to methamphetamine-abusing mothers may experience a neonatal withdrawal syndrome, with symptoms involving of abnormal sleep patterns, poor feeding, tremors, and hypertonia. This withdrawal syndrome is relatively mild and only requires medical intervention in approximately 4% of cases.

Methamphetamine is metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP2D6, so CYP2D6 inhibitors will prolong the elimination half-life of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine also interacts with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), since both MAOIs and methamphetamine increase plasma catecholamines; therefore, concurrent use of both is dangerous. Methamphetamine may decrease the effects of sedatives and depressants and increase the effects of antidepressants and other stimulants as well. Methamphetamine may counteract the effects of antihypertensives and antipsychotics due to its effects on the cardiovascular system and cognition respectively. The pH of gastrointestinal content and urine affects the absorption and excretion of methamphetamine. Specifically, acidic substances will reduce the absorption of methamphetamine and increase urinary excretion, while alkaline substances do the opposite. Due to the effect pH has on absorption, proton pump inhibitors, which reduce gastric acid, are known to interact with methamphetamine.

Pharmacology

This illustration depicts the normal operation of the dopaminergic

terminal to the left, and the dopaminergic terminal in the presence of

methamphetamine to the right. Methamphetamine reverses the action of the

dopamine transporter (DAT) by activating TAAR1

(not shown). TAAR1 activation also causes some of the dopamine

transporters to move into the presynaptic neuron and cease transport

(not shown). At VMAT2 (labeled VMAT), methamphetamine causes dopamine

efflux (release).

Pharmacodynamics

Methamphetamine has been identified as a potent full agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that regulates brain catecholamine systems. Activation of TAAR1 increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production and either completely inhibits or reverses the transport direction of the dopamine transporter (DAT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and serotonin transporter (SERT). When methamphetamine binds to TAAR1, it triggers transporter phosphorylation via protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, ultimately resulting in the internalization or reverse function of monoamine transporters. Methamphetamine is also known to increase intracellular calcium, an effect which is associated with DAT phosphorylation through a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CAMK)-dependent signaling pathway, in turn producing dopamine efflux. TAAR1 also has been shown to reduce the firing rate of neurons through direct activation of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels.[106][107][108] TAAR1 activation by methamphetamine in astrocytes appears to negatively modulate the membrane expression and function of EAAT2, a type of glutamate transporter.In addition to the plasma membrane monoamine transporters, methamphetamine inhibits uptake and induces efflux of neurotransmitters and other substrates at the vesicular monoamine transporters, VMAT1 and VMAT2. In neurons, methamphetamine induces monoamine neurotransmitter efflux through VMAT2, resulting in the outflow of monoamines from synaptic vesicles into the cytosol (intracellular fluid) of the presynaptic neuron. Other transporters that methamphetamine is known to inhibit are SLC22A3 and SLC22A5. SLC22A3 is an extraneuronal monoamine transporter that is present in astrocytes, and SLC22A5 is a high-affinity carnitine transporter.

Methamphetamine is also an agonist of the alpha-2 adrenergic receptors and sigma receptors with a greater affinity for σ1 than σ2, and inhibits monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B). Sigma receptor activation by methamphetamine facilitates its central nervous system stimulant effects and promotes neurotoxicity within the brain. Methamphetamine is known to inhibit the CYP2D6 liver enzyme as well. Dextromethamphetamine is a stronger psychostimulant (approximately ten times on striatal dopamine), but levomethamphetamine has stronger peripheral effects, a longer half-life, and longer perceived effects among addicts. At high doses, both enantiomers of methamphetamine can induce similar stereotypy and methamphetamine psychosis, but levomethamphetamine has shorter psychodynamic effects.

Pharmacokinetics

Following oral administration, methamphetamine is well-absorbed into the bloodstream, with peak plasma methamphetamine concentrations achieved in approximately 3.13–6.3 hours post ingestion. Methamphetamine is also well absorbed following inhalation and following intranasal administration. Due to the high lipophilicity of methamphetamine, it can readily move through the blood–brain barrier faster than other stimulants, where it is more resistant to degradation by monoamine oxidase. The amphetamine metabolite peaks at 10–24 hours. Methamphetamine is excreted by the kidneys, with the rate of excretion into the urine heavily influenced by urinary pH. When taken orally, 30–54% of the dose is excreted in urine as methamphetamine and 10–23% as amphetamine. Following IV doses, about 45% is excreted as methamphetamine and 7% as amphetamine. The half-life of methamphetamine is variable with a range of 5–30 hours.CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase, flavin-containing monooxygenase 3, butyrate-CoA ligase, and glycine N-acyltransferase are the enzymes known to metabolize methamphetamine or its metabolites in humans. The primary metabolites are amphetamine and 4-hydroxymethamphetamine; other minor metabolites include: 4-hydroxyamphetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone, the metabolites of amphetamine. Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are amphetamine, 4‑hydroxyamphetamine, 4‑hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxymethamphetamine, and norephedrine.

Detection in biological fluids

Methamphetamine and amphetamine are often measured in urine or blood as part of a drug test for sports, employment, poisoning diagnostics, and forensics. Chiral techniques may be employed to help distinguish the source the drug to determine whether it was obtained illicitly or legally via prescription or prodrug. Chiral separation is needed to assess the possible contribution of levomethamphetamine, which is an active ingredients in some OTC nasal decongestants, toward a positive test result. Dietary zinc supplements can mask the presence of methamphetamine and other drugs in urine.Chemistry

Pure shards of methamphetamine hydrochloride, also known as crystal meth

Methamphetamine is a chiral compound with two enantiomers, dextromethamphetamine and levomethamphetamine. At room temperature, the free base of methamphetamine is a clear and colorless liquid with an odor characteristic of geranium leaves. It is soluble in diethyl ether and ethanol as well as miscible with chloroform. In contrast, the methamphetamine hydrochloride salt is odorless with a bitter taste. It has a melting point between 170 to 175 °C (338 to 347 °F) and, at room temperature, occurs as white crystals or a white crystalline powder. The hydrochloride salt is also freely soluble in ethanol and water.

Degradation

Bleach exposure time and concentration are correlated with destruction of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine in soils has shown to be a persistent pollutant. Methamphetamine is largely degraded within 30 days in a study of bioreactors under exposure to light in wastewater.Synthesis

Racemic methamphetamine may be prepared starting from phenylacetone by either the Leuckart or reductive amination methods. In the Leuckart reaction, one equivalent of phenylacetone is reacted with two equivalents of N-methylformamide to produce the formyl amide of methamphetamine plus carbon dioxide and methylamine as side products. In this reaction, an iminium cation is formed as an intermediate which is reduced by the second equivalent of N-methylformamide. The intermediate formyl amide is then hydrolyzed under acidic aqueous conditions to yield methamphetamine as the final product. Alternatively, phenylacetone can be reacted with methylamine under reducing conditions to yield methamphetamine.

Methamphetamine synthesis

Methods of methamphetamine synthesis via the Leuckart reaction

History, society, and culture

Pervitin, a methamphetamine brand used by German soldiers during World War II, was dispensed in these tablet containers.

U.S. drug overdose related fatalities in 2017 were more than 72,000, including 10,721 of those related to methamphetamine overdose.

During World War II, methamphetamine was sold in tablet form under the brand name Pervitin (not to be confused with Perviton, which is a synonym for Phenatine), produced by the Berlin-based Temmler pharmaceutical company. It was used extensively by all branches of the combined Wehrmacht armed forces of the Third Reich, and was popular with Luftwaffe pilots in particular, for its performance-enhancing stimulant effects and to induce extended wakefulness. Pervitin became colloquially known among the German troops as "Stuka-Tablets" (Stuka-Tabletten) and "Herman-Göring-Pills" (Hermann-Göring-Pillen). Side effects were so serious that the army sharply cut back its usage in 1940. Historian Lukasz Kamienski says "A soldier going to battle on Pervitin usually found himself unable to perform effectively for the next day or two. Suffering from a drug hangover and looking more like a zombie than a great warrior, he had to recover from the side effects." Some soldiers turned very violent, committing war crimes against civilians; others attacked their own officers.

Obetrol, patented by Obetrol Pharmaceuticals in the 1950s and indicated for treatment of obesity, was one of the first brands of pharmaceutical methamphetamine products. Due to the psychological and stimulant effects of methamphetamine, Obetrol became a popular diet pill in America in the 1950s and 1960s. Eventually, as the addictive properties of the drug became known, governments began to strictly regulate the production and distribution of methamphetamine. For example, during the early 1970s in the United States, methamphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act. Currently, methamphetamine is sold under the trade name Desoxyn, trademarked by the Danish pharmaceutical company Lundbeck. As of January 2013, the Desoxyn trademark had been sold to Italian pharmaceutical company Recordati.