Surgeons repairing a ruptured Achilles tendon on a man

Surgery (from the Greek: χειρουργική cheirourgikē (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via Latin: chirurgiae,

meaning "hand work") is a medical specialty that uses operative manual

and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate or treat a

pathological condition such as a disease or injury, to help improve

bodily function or appearance or to repair unwanted ruptured areas.

The act of performing surgery may be called a "surgical

procedure", "operation", or simply "surgery". In this context, the verb

"operate" means to perform surgery. The adjective "surgical" means

pertaining to surgery; e.g. surgical instruments or surgical nurse. The patient or subject on which the surgery is performed can be a person or an animal. A surgeon is a person who practices surgery and a surgeon's assistant is a person who practices surgical assistance. A surgical team is made up of surgeon, surgeon's assistant, anesthesia provider, circulating nurse and surgical technologist.

Surgery usually spans minutes to hours, but it is typically not an

ongoing or periodic type of treatment. The term "surgery" can also refer

to the place where surgery is performed, or, in British English, simply

the office of a physician, dentist, or veterinarian.

Definitions

Surgery is a technology consisting of a physical intervention on tissues.

As a general rule, a procedure is considered surgical when it

involves cutting of a patient's tissues or closure of a previously

sustained wound. Other procedures that do not necessarily fall under

this rubric, such as angioplasty or endoscopy, may be considered surgery if they involve "common" surgical procedure or settings, such as use of a sterile environment, anesthesia, antiseptic conditions, typical surgical instruments, and suturing or stapling.

All forms of surgery are considered invasive procedures; so-called

"noninvasive surgery" usually refers to an excision that does not

penetrate the structure being excised (e.g. laser ablation of the

cornea) or to a radiosurgical procedure (e.g. irradiation of a tumor).

Types of surgery

Surgical

procedures are commonly categorized by urgency, type of procedure, body

system involved, the degree of invasiveness, and special

instrumentation.

- Based on timing: Elective surgery is done to correct a non-life-threatening condition, and is carried out at the patient's request, subject to the surgeon's and the surgical facility's availability. A semi-elective surgery is one that must be done to avoid permanent disability or death, but can be postponed for a short time. Emergency surgery is surgery which must be done promptly to save life, limb, or functional capacity.

- Based on purpose: Exploratory surgery is performed to aid or confirm a diagnosis. Therapeutic surgery treats a previously diagnosed condition. Cosmetic surgery is done to subjectively improve the appearance of an otherwise normal structure.

- By type of procedure: Amputation involves cutting off a body part, usually a limb or digit; castration is also an example. Resection is the removal of all of an internal organ or body part, or a key part (lung lobe; liver quadrant) of such an organ or body part that has its own name or code designation. Replantation involves reattaching a severed body part. Reconstructive surgery involves reconstruction of an injured, mutilated, or deformed part of the body. Excision is the cutting out or removal of only part of an organ, tissue, or other body part from the patient. Transplant surgery is the replacement of an organ or body part by insertion of another from different human (or animal) into the patient. Removing an organ or body part from a live human or animal for use in transplant is also a type of surgery.

- By body part: When surgery is performed on one organ system or structure, it may be classed by the organ, organ system or tissue involved. Examples include cardiac surgery (performed on the heart), gastrointestinal surgery (performed within the digestive tract and its accessory organs), and orthopedic surgery (performed on bones or muscles).

- By degree of invasiveness of surgical procedures: Minimally-invasive surgery involves smaller outer incision(s) to insert miniaturized instruments within a body cavity or structure, as in laparoscopic surgery or angioplasty. By contrast, an open surgical procedure such as a laparotomy requires a large incision to access the area of interest.

- By equipment used: Laser surgery involves use of a laser for cutting tissue instead of a scalpel or similar surgical instruments. Microsurgery involves the use of an operating microscope for the surgeon to see small structures. Robotic surgery makes use of a surgical robot, such as the Da Vinci or the ZEUS robotic surgical systems , to control the instrumentation under the direction of the surgeon.

Terminology

- Excision surgery names often start with a name for the organ to be excised (cut out) and end in -ectomy.

- Procedures involving cutting into an organ or tissue end in -otomy. A surgical procedure cutting through the abdominal wall to gain access to the abdominal cavity is a laparotomy.

- Minimally invasive procedures, involving small incisions through which an endoscope is inserted, end in -oscopy. For example, such surgery in the abdominal cavity is called laparoscopy.

- Procedures for formation of a permanent or semi-permanent opening called a stoma in the body end in -ostomy.

- Reconstruction, plastic or cosmetic surgery of a body part starts with a name for the body part to be reconstructed and ends in -oplasty. Rhino is used as a prefix for "nose", therefore a rhinoplasty is reconstructive or cosmetic surgery for the nose.

- Repair of damaged or congenital abnormal structure ends in -rraphy.

- Reoperation (return to the operating room) refers to a return to the operating theater after an initial surgery is performed to re-address an aspect of patient care best treated surgically. Reasons for reoperation include persistent bleeding after surgery, development of or persistence of infection.

Description of surgical procedure

Location

Inpatient surgery is performed in a hospital, and the patient stays at least one night in the hospital after the surgery. Outpatient surgery

occurs in a hospital outpatient department or freestanding ambulatory

surgery center, and the patient is discharged the same working day. Office surgery occurs in a physician's office, and the patient is discharged the same working day.

At a hospital, modern surgery is often performed in an operating theater using surgical instruments, an operating table

for the patient, and other equipment. Among United States

hospitalizations for non-maternal and non-neonatal conditions in 2012,

more than one-fourth of stays and half of hospital costs involved stays

that included operating room (OR) procedures. The environment and procedures used in surgery are governed by the principles of aseptic technique:

the strict separation of "sterile" (free of microorganisms) things from

"unsterile" or "contaminated" things. All surgical instruments must be

sterilized,

and an instrument must be replaced or re-sterilized if, it becomes

contaminated (i.e. handled in an unsterile manner, or allowed to touch

an unsterile surface). Operating room staff must wear sterile attire (scrubs,

a scrub cap, a sterile surgical gown, sterile latex or non-latex

polymer gloves and a surgical mask), and they must scrub hands and arms

with an approved disinfectant agent before each procedure.

Preoperative care

Prior to surgery, the patient is given a medical examination, receives certain pre-operative tests, and their physical status is rated according to the ASA physical status classification system.

If these results are satisfactory, the patient signs a consent form and

is given a surgical clearance. If the procedure is expected to result

in significant blood loss, an autologous blood donation may be made some weeks prior to surgery. If the surgery involves the digestive system, the patient may be instructed to perform a bowel prep by drinking a solution of polyethylene glycol the night before the procedure. Patients are also instructed to abstain from food or drink (an NPO order

after midnight on the night before the procedure), to minimize the

effect of stomach contents on pre-operative medications and reduce the

risk of aspiration if the patient vomits during or after the procedure.

Some medical systems have a practice of routinely performing

chest x-rays before surgery. The premise behind this practice is that

the physician might discover some unknown medical condition which would

complicate the surgery, and that upon discovering this with the chest

x-ray, the physician would adapt the surgery practice accordingly. In fact, medical specialty professional organizations recommend against routine pre-operative chest x-rays for patients who have an unremarkable medical history and presented with a physical exam which did not indicate a chest x-ray.

Routine x-ray examination is more likely to result in problems like

misdiagnosis, over-treatment, or other negative outcomes than it is to

result in a benefit to the patient. Likewise, other tests including complete blood count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, basic metabolic panel, and urinalysis should not be done unless the results of these tests can help evaluate surgical risk.

Staging for surgery

In the pre-operative holding area, the patient changes out of his or

her street clothes and is asked to confirm the details of his or her

surgery. A set of vital signs are recorded, a peripheral IV line is placed, and pre-operative medications (antibiotics, sedatives, etc.) are given.

When the patient enters the operating room, the skin surface to be

operated on, called the operating field, is cleaned and prepared by

applying an antiseptic such as chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine

to reduce the possibility of infection. If hair is present at the

surgical site, it is clipped off prior to prep application. The patient

is assisted by an anesthesiologist or resident to make a specific surgical position,

then sterile drapes are used to cover the surgical site or at least a

wide area surrounding the operating field; the drapes are clipped to a

pair of poles near the head of the bed to form an "ether screen", which

separates the anesthetist/anesthesiologist's working area (unsterile) from the surgical site (sterile).

Anesthesia is administered to prevent pain from an incision, tissue manipulation and suturing. Based on the procedure, anesthesia may be provided locally or as general anesthesia. Spinal anesthesia

may be used when the surgical site is too large or deep for a local

block, but general anesthesia may not be desirable. With local and

spinal anesthesia, the surgical site is anesthetized, but the patient

can remain conscious or minimally sedated. In contrast, general

anesthesia renders the patient unconscious and paralyzed during surgery.

The patient is intubated and is placed on a mechanical ventilator, and anesthesia is produced by a combination of injected and inhaled agents.

Choice of surgical method and anesthetic technique aims to reduce the risk of complications, shorten the time needed for recovery and minimize the surgical stress response.

Surgery

An incision is made to access the surgical site. Blood vessels may be clamped or cauterized

to prevent bleeding, and retractors may be used to expose the site or

keep the incision open. The approach to the surgical site may involve

several layers of incision and dissection, as in abdominal surgery,

where the incision must traverse skin, subcutaneous tissue, three layers

of muscle and then the peritoneum. In certain cases, bone may be cut to further access the interior of the body; for example, cutting the skull for brain surgery or cutting the sternum for thoracic (chest) surgery to open up the rib cage. Whilst in surgery aseptic technique

is used to prevent infection or further spreading of the disease. The

surgeons' and assistants' hands, wrists and forearms are washed

thoroughly for at least 4 minutes to prevent germs getting into the

operative field, then sterile gloves are placed onto their hands. An

antiseptic solution is applied to the area of the patient's body that

will be operated on. Sterile drapes are placed around the operative

site. Surgical masks are worn by the surgical team to avoid germs on

droplets of liquid from their mouths and noses from contaminating the

operative site.

Work to correct the problem in body then proceeds. This work may involve:

- excision – cutting out an organ, tumor, or other tissue.

- resection – partial removal of an organ or other bodily structure.

- reconnection of organs, tissues, etc., particularly if severed. Resection of organs such as intestines involves reconnection. Internal suturing or stapling may be used. Surgical connection between blood vessels or other tubular or hollow structures such as loops of intestine is called anastomosis.

- Reduction – the movement or realignment of a body part to its normal position. e.g. Reduction of a broken nose involves the physical manipulation of the bone or cartilage from their displaced state back to their original position to restore normal airflow and aesthetics.

- ligation – tying off blood vessels, ducts, or "tubes".

- grafts – may be severed pieces of tissue cut from the same (or different) body or flaps of tissue still partly connected to the body but resewn for rearranging or restructuring of the area of the body in question. Although grafting is often used in cosmetic surgery, it is also used in other surgery. Grafts may be taken from one area of the patient's body and inserted to another area of the body. An example is bypass surgery, where clogged blood vessels are bypassed with a graft from another part of the body. Alternatively, grafts may be from other persons, cadavers, or animals.

- insertion of prosthetic parts when needed. Pins or screws to set and hold bones may be used. Sections of bone may be replaced with prosthetic rods or other parts. Sometimes a plate is inserted to replace a damaged area of skull. Artificial hip replacement has become more common. Heart pacemakers or valves may be inserted. Many other types of prostheses are used.

- creation of a stoma, a permanent or semi-permanent opening in the body

- in transplant surgery, the donor organ (taken out of the donor's body) is inserted into the recipient's body and reconnected to the recipient in all necessary ways (blood vessels, ducts, etc.).

- arthrodesis – surgical connection of adjacent bones so the bones can grow together into one. Spinal fusion is an example of adjacent vertebrae connected allowing them to grow together into one piece.

- modifying the digestive tract in bariatric surgery for weight loss.

- repair of a fistula, hernia, or prolapse

- other procedures, including:

- clearing clogged ducts, blood or other vessels

- removal of calculi (stones)

- draining of accumulated fluids

- debridement – removal of dead, damaged, or diseased tissue

Blood or blood expanders may be administered to compensate for blood lost during surgery. Once the procedure is complete, sutures or staples

are used to close the incision. Once the incision is closed, the

anesthetic agents are stopped or reversed, and the patient is taken off

ventilation and extubated (if general anesthesia was administered).

Post-operative care

After completion of surgery, the patient is transferred to the post anesthesia care unit

and closely monitored. When the patient is judged to have recovered

from the anesthesia, he/she is either transferred to a surgical ward

elsewhere in the hospital or discharged home. During the post-operative

period, the patient's general function is assessed, the outcome of the

procedure is assessed, and the surgical site is checked for signs of

infection. There are several risk factors associated with postoperative

complications, such as immune deficiency and obesity. Obesity has long

been considered a risk factor for adverse post-surgical outcomes. It has

been linked to many disorders such as obesity hypoventilation syndrome, atelectasis and pulmonary embolism, adverse cardiovascular effects, and wound healing complications.

If removable skin closures are used, they are removed after 7 to 10

days post-operatively, or after healing of the incision is well under

way.

It is not uncommon for surgical drains

to be required to remove blood or fluid from the surgical wound during

recovery. Mostly these drains stay in until the volume tapers off, then

they are removed. These drains can become clogged, leading to abscess.

Postoperative therapy may include adjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or administration of medication such as anti-rejection medication for transplants. Other follow-up studies or rehabilitation may be prescribed during and after the recovery period.

The use of topical antibiotics on surgical wounds to reduce infection rates has been questioned. Antibiotic ointments are likely to irritate the skin, slow healing, and could increase risk of developing contact dermatitis and antibiotic resistance.

It has also been suggested that topical antibiotics should only be used

when a person shows signs of infection and not as a preventative. A systematic review published by Cochrane (organization)

in 2016, though, concluded that topical antibiotics applied over

certain types of surgical wounds reduce the risk of surgical site

infections, when compared to no treatment or use of antiseptics.

The review also did not find conclusive evidence to suggest that

topical antibiotics increased the risk of local skin reactions or

antibiotic resistance.

Through a retrospective analysis of national administrative data,

the association between mortality and day of elective surgical

procedure suggests a higher risk in procedures carried out later in the

working week and on weekends. The odds of death were 44% and 82% higher

respectively when comparing procedures on a Friday to a weekend

procedure. This “weekday effect” has been postulated to be from several

factors including poorer availability of services on a weekend, and

also, decrease number and level of experience over a weekend.

Epidemiology

United States

In

2011, of the 38.6 million hospital stays in U.S. hospitals, 29%

included at least one operating room procedure. These stays accounted

for 48% of the total $387 billion in hospital costs.

The overall number of procedures remained stable from 2001 to

2011. In 2011, over 15 million operating room procedures were performed

in U.S. hospitals.

Data from 2003 to 2011 showed that U.S. hospital costs were

highest for the surgical service line; the surgical service line costs

were $17,600 in 2003 and projected to be $22,500 in 2013. For hospital stays in 2012 in the United States, private insurance had the highest percentage of surgical expenditure. in 2012, mean hospital costs in the United States were highest for surgical stays.

Special populations

Elderly people

Older adults have widely varying physical health. Frail elderly

people are at significant risk of post-surgical complications and the

need for extended care. Assessment of older patients before elective

surgery can accurately predict the patients' recovery trajectories. One frailty scale uses five items: unintentional weight loss, muscle weakness,

exhaustion, low physical activity, and slowed walking speed. A healthy

person scores 0; a very frail person scores 5. Compared to non-frail

elderly people, people with intermediate frailty scores (2 or 3) are

twice as likely to have post-surgical complications, spend 50% more time

in the hospital, and are three times as likely to be discharged to a

skilled nursing facility instead of to their own homes.

Frail elderly patients (score of 4 or 5) have even worse outcomes,

with the risk of being discharged to a nursing home rising to twenty

times the rate for non-frail elderly people.

Children

Surgery

on children requires considerations which are not common in adult

surgery. Children and adolescents are still developing physically and

mentally making it difficult for them to make informed decisions and

give consent for surgical treatments. Bariatric surgery in youth is among the controversial topics related to surgery in children.

Vulnerable populations

Doctors perform surgery with the consent of the patient. Some patients are able to give better informed consent than others. Populations such as incarcerated persons, people living with dementia,

the mentally incompetent, persons subject to coercion, and other people

who are not able to make decisions with the same authority as a typical

patient have special needs when making decisions about their personal

healthcare, including surgery.

In low- and middle-income countries

In

2014, the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery was launched to examine

the case for surgery as an integral component of global health care and

to provide recommendations regarding the delivery of surgical and

anesthesia services in low and middle income countries. Among the conclusions in this study, two primary conclusions were reached:

- Five billion people worldwide lack access to safe, timely, and affordable surgical and anesthesia care. Areas in which especially large proportions of the population lack access include Sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, Central Asia and, to a lesser extent, Russia and China. Of the estimated 312.9 million surgical procedures undertaken worldwide in 2012, only 6.3% were done in countries comprising the poorest 37.3% of the world's population.

- An additional 143 million surgical procedures are needed each year to prevent unnecessary death and disability.

Globally, 4.2 million people are estimated to die within 30 days of

surgery each year, with half of these occurring in low- and

middle-income countries.

A prospective study of 10,745 adult patients undergoing emergency

abdominal surgery from 357 centers across 58 countries found that

mortality is three times higher in low- compared with high-human

development index (HDI) countries even when adjusted for prognostic

factors.

In this study the overall global mortality rate was 1·6 per cent at

24 hours (high HDI 1·1 per cent, middle HDI 1·9 per cent, low HDI 3·4

per cent), increasing to 5·4 per cent by 30 days (high HDI 4·5 per cent,

middle HDI 6·0 per cent, low HDI 8·6 per cent; P < 0·001). A

sub-study of 1,409 children undergoing emergency abdominal surgery from

253 centers across 43 countries found that adjusted mortality in

children following surgery may be as high as 7 times greater in low-HDI

and middle-HDI countries compared with high-HDI countries. This

translate to 40 excess deaths per 1000 procedures performed in these

settings. Patient safety factors were suggested to play an important role, with use of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist associated with reduced mortality at 30 days.

Human rights

Access

to surgical care is increasingly recognized as an integral aspect of

healthcare, and therefore is evolving into a normative derivation of

human right to health. The ICESCR Article 12.1 and 12.2 define the human right to health as “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” In the August 2000, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

(CESCR) interpreted this to mean “right to the enjoyment of a variety

of facilities, goods, services, and conditions necessary for the

realization of the highest attainable health”. Surgical care can be thereby viewed as a positive right – an entitlement to protective healthcare.

Woven through the International Human and Health Rights

literature is the right to be free from surgical disease. The 1966

ICESCR Article 12.2a described the need for “provision for the reduction

of the stillbirth-rate and of infant mortality and for the healthy

development of the child” which was subsequently interpreted to mean “requiring measures to improve… emergency obstetric services”.

Article 12.2d of the ICESCR stipulates the need for “the creation of

conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical

attention in the event of sickness”,

and is interpreted in the 2000 comment to include timely access to

“basic preventative, curative services… for appropriate treatment of injury and disability.”. Obstetric care shares close ties with reproductive rights, which includes access to reproductive health.

Surgeons and public health advocates, such as Kelly McQueen, have described surgery as “Integral to the right to health”. This is reflected in the establishment of the WHO Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care in 2005, the 2013 formation of the Lancet Commission for Global Surgery, the 2015 World Bank Publication of Volume 1 of its Disease Control Priorities “Essential Surgery”, and the 2015 World Health Assembly 68.15 passing of the Resolution for Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage.

The Lancet Commission for Global Surgery outlined the need for access

to “available, affordable, timely and safe” surgical and anesthesia

care; dimensions paralleled in ICESCR General Comment No. 14, which similarly outlines need for available, accessible, affordable and timely healthcare.

History

Plates vi & vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus, an Egyptian surgical treatise

Trepanation

Surgical treatments date back to the prehistoric era. The oldest for which there is evidence is trepanation, in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the skull, thus exposing the dura mater in order to treat health problems related to intracranial pressure and other diseases.

Ancient Egypt

Prehistoric surgical techniques are seen in Ancient Egypt, where a mandible dated to approximately 2650 BC shows two perforations just below the root of the first molar, indicating the draining of an abscessed tooth.

Surgical texts from ancient Egypt date back about 3500 years ago.

Surgical operations were performed by priests, specialized in medical

treatments similar to today, and used sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey.

India

Sushruta, the author of Sushruta Samhita, one of the oldest texts on surgery

Remains from the early Harappan periods of the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300 BC) show evidence of teeth having been drilled dating back 9,000 years. Susruta was an ancient Indian surgeon commonly credited as the author of the treatise Sushruta Samhita. He is dubbed as the "founding father of surgery" and his period is usually placed between the period of 1200–600 BC. One of the earliest known mention of the name is from the Bower Manuscript where Sushruta is listed as one of the ten sages residing in the Himalayas. Texts also suggest that he learned surgery at Kasi from Lord Dhanvantari, the god of medicine in Hindu mythology.

It is one of the oldest known surgical texts and it describes in detail

the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous

ailments, as well as procedures on performing various forms of cosmetic

surgery, plastic surgery and rhinoplasty.

Ancient Greece

Hippocrates

stated in the oath (c. 400 BC) that general physicians must never

practice surgery and that surgical procedures are to be conducted by

specialists

In ancient Greece, temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Greek: Ασκληπιεία, sing. Asclepieion Ασκληπιείον), functioned as centers of medical advice, prognosis, and healing. In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus,

some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal

abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic

enough to have taken place. The Greek Galen

was one of the greatest surgeons of the ancient world and performed

many audacious operations – including brain and eye surgery – that were

not tried again for almost two millennia.

Islamic World

Surgery was developed to a high degree in the Islamic world. Abulcasis (Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi), an Andalusian-Arab physician and scientist who practiced in the Zahra suburb of Córdoba. His works on surgery, largely based upon Paul of Aegina's Pragmateia, were influential.

Early modern Europe

Ambroise Paré (c. 1510–1590), father of modern military surgery.

12th century medieval eye surgery in Italy

In Europe, the demand grew for surgeons to formally study for many years before practicing; universities such as Montpellier, Padua and Bologna were particularly renowned. In the 12th century, Rogerius Salernitanus composed his Chirurgia, laying the foundation for modern Western surgical manuals. Barber-surgeons

generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the

development of academic surgery as a specialty of medicine, rather than

an accessory field. Basic surgical principles for asepsis etc., are known as Halsteads principles.

There were some important advances to the art of surgery during this period. The professor of anatomy at the University of Padua, Andreas Vesalius, was a pivotal figure in the Renaissance transition from classical medicine and anatomy based on the works of Galen, to an empirical approach of 'hands-on' dissection. In his anatomic treatis De humani corporis fabrica,

he exposed the many anatomical errors in Galen and advocated that all

surgeons should train by engaging in practical dissections themselves.

The second figure of importance in this era was Ambroise Paré (sometimes spelled "Ambrose"),

a French army surgeon from the 1530s until his death in 1590. The

practice for cauterizing gunshot wounds on the battlefield had been to

use boiling oil; an extremely dangerous and painful procedure. Paré

began to employ a less irritating emollient, made of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine. He also described more efficient techniques for the effective ligation of the blood vessels during an amputation.

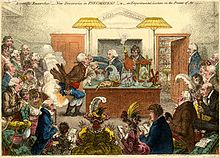

Modern surgery

The discipline of surgery was put on a sound, scientific footing during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe. An important figure in this regard was the Scottish surgical scientist, John Hunter, generally regarded as the father of modern scientific surgery. He brought an empirical and experimental

approach to the science and was renowned around Europe for the quality

of his research and his written works. Hunter reconstructed surgical

knowledge from scratch; refusing to rely on the testimonies of others,

he conducted his own surgical experiments to determine the truth of the

matter. To aid comparative analysis, he built up a collection of over

13,000 specimens of separate organ systems, from the simplest plants and

animals to humans.

He greatly advanced knowledge of venereal disease and introduced many new techniques of surgery, including new methods for repairing damage to the Achilles tendon and a more effective method for applying ligature of the arteries in case of an aneurysm. He was also one of the first to understand the importance of pathology, the danger of the spread of infection and how the problem of inflammation of the wound, bone lesions and even tuberculosis

often undid any benefit that was gained from the intervention. He

consequently adopted the position that all surgical procedures should be

used only as a last resort.

Other important 18th- and early 19th-century surgeons included Percival Pott (1713–1788) who described tuberculosis on the spine and first demonstrated that a cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen (he noticed a connection between chimney sweep's exposure to soot and their high incidence of scrotal cancer). Astley Paston Cooper (1768–1841) first performed a successful ligation of the abdominal aorta, and James Syme (1799–1870) pioneered the Symes Amputation for the ankle joint and successfully carried out the first hip disarticulation.

Modern pain control through anesthesia was discovered in the mid-19th century. Before the advent of anesthesia, surgery was a traumatically painful procedure and surgeons were encouraged to be as swift as possible to minimize patient suffering. This also meant that operations were largely restricted to amputations

and external growth removals. Beginning in the 1840s, surgery began to

change dramatically in character with the discovery of effective and

practical anesthetic chemicals such as ether, first used by the American surgeon Crawford Long, and chloroform, discovered by Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson and later pioneered by John Snow, physician to Queen Victoria.

In addition to relieving patient suffering, anesthesia allowed more

intricate operations in the internal regions of the human body. In

addition, the discovery of muscle relaxants such as curare allowed for safer applications.

Infection and antisepsis

Unfortunately,

the introduction of anesthetics encouraged more surgery, which

inadvertently caused more dangerous patient post-operative infections.

The concept of infection was unknown until relatively modern times. The

first progress in combating infection was made in 1847 by the Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis

who noticed that medical students fresh from the dissecting room were

causing excess maternal death compared to midwives. Semmelweis, despite

ridicule and opposition, introduced compulsory hand washing for everyone

entering the maternal wards and was rewarded with a plunge in maternal

and fetal deaths; however, the Royal Society dismissed his advice.

Joseph Lister, pioneer of antiseptic surgery

Until the pioneering work of British surgeon Joseph Lister in the 1860s, most medical men believed that chemical damage from exposures to bad air was responsible for infections in wounds, and facilities for washing hands or a patient's wounds were not available. Lister became aware of the work of French chemist Louis Pasteur, who showed that rotting and fermentation could occur under anaerobic conditions if micro-organisms were present. Pasteur suggested three methods to eliminate the micro-organisms responsible for gangrene: filtration, exposure to heat, or exposure to chemical solutions. Lister confirmed Pasteur's conclusions with his own experiments and decided to use his findings to develop antiseptic

techniques for wounds. As the first two methods suggested by Pasteur

were inappropriate for the treatment of human tissue, Lister

experimented with the third, spraying carbolic acid on his instruments. He found that this remarkably reduced the incidence of gangrene and he published his results in The Lancet. Later, on 9 August 1867, he read a paper before the British Medical Association in Dublin, on the Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery, which was reprinted in The British Medical Journal.

His work was groundbreaking and laid the foundations for a rapid

advance in infection control that saw modern antiseptic operating

theaters widely used within 50 years.

Lister continued to develop improved methods of antisepsis and asepsis

when he realised that infection could be better avoided by preventing

bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the

rise of sterile surgery. Lister introduced the Steam Steriliser to sterilize

equipment, instituted rigorous hand washing and later implemented the

wearing of rubber gloves. These three crucial advances – the adoption of

a scientific methodology toward surgical operations, the use of

anesthetic and the introduction of sterilized equipment – laid the

groundwork for the modern invasive surgical techniques of today.

The use of X-rays as an important medical diagnostic tool began with their discovery in 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen. He noticed that these rays could penetrate the skin, allowing the skeletal structure to be captured on a specially treated photographic plate.