| |

| Developer | |

|---|---|

| Written in | C, C++ |

| OS family | Linux |

| Working state | Preinstalled on Chromebooks, Chromeboxes, Chromebits, Chromebase |

| Initial release | June 15, 2011 |

| Latest release | 72.0.3626.122 |

| Latest preview |

|

| Update method | Rolling release |

| Platforms | x86, ARMv7, x64 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic (Linux kernel) |

| Default user interface | WIMP-based [web browser] windows |

| License | Google Chrome OS Terms of Service |

| Official website | www |

Chrome OS is an operating system designed by Google that is based on the Linux kernel and uses the Google Chrome web browser as its principal user interface. As a result, Chrome OS primarily supports web applications.

Google announced the project in July 2009, conceiving it as an operating system in which both applications and user data reside in the cloud: hence Chrome OS primarily runs web applications. Source code and a public demo came that November. The first Chrome OS laptop, known as a Chromebook, arrived in May 2011. Initial Chromebook shipments from Samsung and Acer occurred in July 2011.

Chrome OS has an integrated media player and file manager. It supports Chrome Apps, which resemble native applications, as well as remote access to the desktop. Android applications started to become available for the operating system in 2014, and in 2016, access to Android apps in the entire Google Play Store was introduced on supported Chrome OS devices. Reception was initially skeptical, with some observers arguing that a browser running on any operating system was functionally equivalent. As more Chrome OS machines have entered the market, the operating system is now seldom evaluated apart from the hardware that runs it.

Chrome OS is only available pre-installed on hardware from Google manufacturing partners, but there are unofficial methods that allow it to be installed in other equipment. An open source equivalent, Chromium OS, can be compiled from downloaded source code. Early on, Google provided design goals for Chrome OS, but has not otherwise released a technical description.

History

Google announced Chrome OS on July 7, 2009, describing it as an operating system in which both applications and user data reside in the cloud.

To ascertain marketing requirements, the company relied on informal

metrics, including monitoring the usage patterns of some 200 Chrome OS

machines used by Google employees. Developers also noted their own usage

patterns. Matthew Papakipos, former

engineering director for the Chrome OS project, put three machines in

his house and found himself logging in for brief sessions: to make a

single search query or send a short email.

Chrome OS was initially intended for secondary devices like netbooks, not as a user's primary PC. While Chrome OS supports hard disk drives, Google has requested that its hardware partners use solid-state drives "for performance and reliability reasons"

as well as the lower capacity requirements inherent in an operating

system that accesses applications and most user data on remote servers.

In November 2009 Matthew Papakipos, engineering director for the Chrome

OS, claimed that the Chrome OS consumes one-sixtieth as much drive space

as Windows 7. The recovery images Google provides for Chrome OS range between 1 and 3 GB.

On November 19, 2009, Google released Chrome OS's source code as the Chromium OS project. At a November 19, 2009, news conference, Sundar Pichai,

at the time Google's vice president overseeing Chrome, demonstrated an

early version of the operating system. He previewed a desktop which

looked very similar to the Chrome browser, and in addition to the

regular browser tabs, also had application tabs, which take less space

and can be pinned for easier access. At the conference, the operating

system booted up in seven seconds, a time Google said it would work to reduce. Additionally, Chris Kenyon, vice president of OEM services at Canonical Ltd,

announced that Canonical was under contract to contribute engineering

resources to the project with the intent to build on existing open

source components and tools where feasible.

Early Chromebooks

In 2010, Google released the unbranded Cr-48 Chromebook in a pilot program. The launch date for retail hardware featuring Chrome OS was delayed from late 2010 until the next year. On 11 May 2011, Google announced two Chromebooks from Acer and Samsung at Google I/O. The Samsung model was released on 15 June 2011, but the Acer was delayed until mid-July. In August 2011, Netflix

announced official support for Chrome OS through its streaming service,

allowing Chromebooks to watch streaming movies and TV shows via

Netflix. At the time, other devices had to use Microsoft Silverlight to play videos from Netflix. Later in that same month, Citrix released a client application for Chrome OS, allowing Chromebooks to access Windows applications and desktops remotely.

Dublin City University became the first educational institution in

Europe to provide Chromebooks for its students when it announced an

agreement with Google in September 2011.

Expansion

Samsung Chromebook

By 2012, demand for Chromebooks had begun to grow, and Google

announced a new range of devices, designed and manufactured by Samsung.

In so doing, they also released the first Chromebox, the Samsung Series 3, which was Chrome OS's entrance into the world of desktop computers.

Although they were faster than the previous range of devices, they were

still underpowered compared to other desktops and laptops of the time,

fitting in more closely with the Netbook

market. Only months later, in October, Samsung and Google released a

new Chromebook at a significantly lower price point ($250, compared to

the previous Series 5 Chromebooks' $450). It was the first Chromebook to use an ARM processor, one from Samsung's Exynos

line. In order to reduce the price, Google and Samsung also reduced the

memory and screen resolution of the device. An advantage of using the

ARM processor, however, was that the Chromebook didn't require a fan.

Acer followed quickly after with the C7 Chromebook, priced even lower

($199), but containing an Intel Celeron processor. One notable way which Samsung reduced the cost of the C7 was to use a laptop hard disk rather than a solid state drive.

In April 2012, Google made the first update to Chrome OS's user

interface since the operating system had launched, introducing a

hardware-accelerated window manager called "Aura" along with a

conventional taskbar. The additions marked a departure from the

operating system's original concept of a single browser with tabs and

gave Chrome OS the look and feel of a more conventional desktop

operating system. "In a way, this almost feels as if Google is admitting

defeat here", wrote Frederic Lardinois on TechCrunch. He argued that

Google had traded its original version of simplicity for greater

functionality. "That’s not necessarily a bad thing, though, and may just

help Chrome OS gain more mainstream acceptance as new users will surely

find it to be a more familiar experience." Lenovo and HP followed Samsung and Acer in manufacturing Chromebooks in early 2013 with their own models.

Lenovo specifically targeted their Chromebook at students, headlining

their press release with "Lenovo Introduces Rugged ThinkPad Chromebook

for Schools".

When Google released Google Drive, they also included Drive integration in the next version of Chrome OS (version 20), released in July 2012. While Chrome OS had supported Flash since 2010, by the end of 2012 it had been fully sandboxed, preventing issues with Flash from affecting other parts of Chrome OS. This affected all versions of Chrome including Chrome OS.

Chromebook Pixel

Chromebook Pixel (WiFi) open

Up to this point, Google had never made their own Chrome OS device. Instead, Chrome OS devices were much more similar to their Nexus

line of Android phones, with each Chrome OS device being designed,

manufactured, and marketed by third party manufacturers, but with Google

controlling the software. However, in February 2013 this changed when

Google released the Chromebook Pixel. The Chromebook Pixel was a departure from previous devices. Not only was it entirely Google-branded, but it contained an Intel i5

processor, a high-resolution (2,560x1,700) touchscreen display, and

came at a price point more competitive with business laptops.

Controversial Popularity

By

the end of 2013, analysts were undecided on the future of Chrome OS.

Although there had been articles predicting the demise of Chrome OS

since 2009, Chrome OS device sales continued to increase substantially year-over-year. In mid 2014, Time Magazine

published an article titled "Depending on Who's Counting, Chromebooks

are Either an Enormous Hit or Totally Irrelevant", which detailed the

differences in opinion. This controversy was further spurred by the fact that Intel

seemed to decide Chrome OS was a beneficial market for it, holding

their own Chrome OS events where they announced new Intel-based Chromebooks, Chromeboxes, and an all-in-one from LG called the Chromebase.

Seizing the opportunity created by the end of life for Windows XP, Google pushed hard to sell Chromebooks to businesses, offering significant discounts in early 2014.

Pwnium competition

In March 2014, Google hosted a hacking contest aimed at computer security experts called "Pwnium". Similar to the Pwn2Own

contest, they invited hackers from around the world to find exploits in

Chrome OS, with prizes available for attacks. Two exploits were

demonstrated there, and a third was demonstrated at that year's Pwn2Own

competition. Google patched the issues within a week.

Material Design and App Runtime for Chrome

Although the Google Native Client has been available on Chrome OS since 2010,

there originally were few Native Client apps available, and most Chrome

OS apps were still web apps. However, in June 2014, Google announced at

Google I/O

that Chrome OS would both synchronise with Android phones to share

notifications and begin to run Android apps, installed directly from the

Google Play Store. This, along with the broadening selection of Chromebooks, provided an interesting future for Chrome OS.

At the same time, Google was also moving towards the then-new Material Design visual language for its products, which it would bring to its web products as well as Android Lollipop. One of the first Material Design items to come to Chrome OS was a new default wallpaper,

though Google did release some screenshots of a Material Design

experiment for Chrome OS that never made it into the stable version.

Chromebox for Meetings

In

an attempt to expand its enterprise offerings, Google released the

Chromebox for Meetings in February 2014. The Chromebox for Meetings is a

kit for conference rooms containing a Chromebox, a camera, a unit

containing both a noise-cancelling microphone and speakers, and a remote

control. It supports Google Hangouts meetings, Vidyo video conferences, and conference calls from UberConference.

Several partners announced Chromebox for Meetings models with Google,

and in 2016 Google announced an all-in-one Chromebase for Meetings for

smaller meeting rooms.

Hardware

A Chromebook.

Laptops running Chrome OS are known collectively as "Chromebooks". The first was the CR-48, a reference hardware design

that Google gave to testers and reviewers beginning in December 2010.

Retail machines followed in May 2011. A year later, in May 2012, a

desktop design marketed as a "Chromebox" was released by Samsung. In March 2015 a partnership with AOPEN was announced and the first commercial Chromebox was developed.

In early 2014, LG Electronics introduced the first device belonging to the new all-in-one form factor called "Chromebase". Chromebase devices are essentially Chromebox hardware inside a monitor with built-in camera, microphone and speakers.

The Chromebit is an HDMI dongle running Chrome OS. When placed in an HDMI slot on a television set or computer monitor, the device turns that display into a personal computer. The device was announced in March 2015 and shipped that November.

Chrome OS supports dual-monitor setups, on devices with a video-out port.

Applications

Chrome OS running six different web browsers

Initially, Chrome OS was almost a pure web thin client operating system that relied primarily on servers to host web applications and related data storage. Google gradually began encouraging developers to create "packaged applications", and later, Chrome Apps. The latter employs HTML5, CSS, Adobe Shockwave, and JavaScript to provide a user experience closer to a native application.

In September 2014, Google launched App Runtime for Chrome (beta), which allowed certain ported Android applications to run on Chrome OS. Runtime was launched with four Android applications: Duolingo, Evernote, Sight Words, and Vine. In 2016, Google made the Google Play Store available for Chrome OS, making most Android apps available for supported Chrome OS devices.

Google announced in 2018 that Chrome OS would be getting support for desktop Linux apps. This capability was released to the stable channel with Chrome 69 in October 2018, but was still marked as beta.

Chrome Apps

Google has encouraged developers to build not just conventional Web

applications for Chrome OS, but Chrome Apps (formerly known as Packaged

apps). From a user perspective, Chrome Apps resemble conventional native

applications: they can be launched outside of the Chrome browser, are

offline by default, can manage multiple windows, and interact with other

applications. Technologies employed include HTML5, JavaScript, and CSS.

Integrated media player, file manager

Google integrates a media player

into both Chrome OS and the Chrome browser, enabling users to play back

MP3s, view JPEGs, and handle other multimedia files while offline. It supports DRM videos.

Chrome OS also includes an integrated file manager, resembling

those found on other operating systems, with the ability to display

directories and the files they contain from both Google Drive and local

storage, as well as to preview and manage file contents using a variety

of Web applications, including Google Docs and Box.

Since January 2015, Chrome OS can also integrate additional storage

sources into the file manager, relying on installed extensions that use

the File System Provider API.

Remote application access and virtual desktop access

In

June 2010, Google software engineer Gary Kačmarčík wrote that Chrome OS

will access remote applications through a technology unofficially

called "Chromoting", which would resemble Microsoft's Remote Desktop Connection. The name has since been changed to "Chrome Remote Desktop", and is like "running an application via Remote Desktop Services or by first connecting to a host machine by using RDP or VNC". Initial roll-outs of Chrome OS laptops (Chromebooks) indicate an interest in enabling users to access virtual desktops.

Android applications

At Google I/O 2014, a proof of concept showing Android applications, including Flipboard, running on Chrome OS was presented. In September 2014, Google introduced a beta version of the App Runtime for Chrome (ARC), which allows selected Android applications to be used on Chrome OS, using a Native Client-based

environment that provides the platforms necessary to run Android

software. Android applications do not require any modifications to run

on Chrome OS, but may be modified to better support a mouse and keyboard

environment. At its introduction, Chrome OS support was only available

for selected Android applications.

In 2016, Google introduced the ability to run Android apps on supported Chrome OS devices, with access to the entire Google Play Store. The previous Native Client-based solution was dropped in favor of a container containing Android's frameworks and dependencies (initially based on Android 6.0),

which allows Android apps to have direct access to the Chrome OS

platform, and allow the OS to interact with Android contracts such as

sharing. Engineering director Zelidrag Hornung explained that ARC had

been scrapped due to its limitations, including its incompatibility with

the Android Native Development Toolkit (NDK), and that it was unable to pass Google's own compatibility test suite.

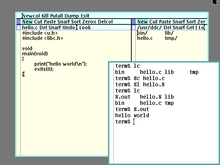

Linux Apps

Since 2013 it has been possible to run Linux applications in Chrome OS through the use of Crouton, a third-party set of scripts that allows access to a Linux distribution such as Ubuntu. However, in 2018 Google announced that desktop Linux apps were officially coming to Chrome OS.

The main benefit claimed by Google of their official Linux application

support is that it can run without enabling developer mode, keeping many

of the security features of Chrome OS. It was noticed in the Chromium

OS source code in early 2018. Early parts of Crostini were made available for the Google Pixelbook via the dev channel in February 2018 as part of Chrome OS version 66, and it was enabled by default via the beta channel for testing on a variety of chromebooks in August 2018 with version 69.

Architecture

Google's project for supporting Linux applications in Chrome OS is called Crostini, named for the Italian bread-based starter,

and as a pun on Crouton. Crostini runs a virtual machine through a

virtual machine monitor called crosvm, which uses Linux's built-in KVM

virtualization tool. Although Crosvm supports multiple virtual

machines, the one used for running Linux apps, Termina, contains a basic

Chrome OS kernel and userland utilities, in which it runs containers

based on Linux containers (specifically LXD).

Architecture

Chrome OS is built on top of the Linux kernel. Originally based on Ubuntu, its base was changed to Gentoo Linux in February 2010.

In preliminary design documents for the Chromium OS open source

project, Google described a three-tier architecture: firmware, browser

and window manager, and system-level software and userland services.

- The firmware contributes to fast boot time by not probing for hardware, such as floppy disk drives, that are no longer common on computers, especially netbooks. The firmware also contributes to security by verifying each step in the boot process and incorporating system recovery.

- System-level software includes the Linux kernel that has been patched to improve boot performance. Userland software has been trimmed to essentials, with management by Upstart, which can launch services in parallel, re-spawn crashed jobs, and defer services in the interest of faster booting.

- The window manager handles user interaction with multiple client windows much like other X window managers.

Security

In

March 2010, Google software security engineer Will Drewry discussed

Chrome OS security. Drewry described Chrome OS as a "hardened" operating

system featuring auto-updating and sandbox features that will reduce malware exposure. He said that Chrome OS netbooks will be shipped with Trusted Platform Module

(TPM), and include both a "trusted bootpath" and a physical switch

under the battery compartment that actuates a developer mode. That mode

drops some specialized security functions but increases developer

flexibility. Drewry also emphasized that the open source nature of the

operating system will contribute greatly to its security by allowing

constant developer feedback.

At a December 2010 press conference, Google claimed that Chrome

OS would be the most secure consumer operating system due in part to a verified boot ability, in which the initial boot code, stored in read-only memory, checks for system compromises.

Shell access

Chrome OS includes the Chrome Shell, or "crosh", which documents minimal functionality such as ping and SSH at crosh start-up.

In developer mode, a full-featured bash shell (which is supposed to be used for development purposes) can be opened via VT-2, and is also accessible using the crosh command

shell. To access full privileges in shell (e.g. sudo) a root password is requested. For some time the default was "chronos" in Chrome OS and "facepunch" in Chrome OS Vanilla and later the default was empty, and instructions on updating it were displayed at each login.

Open source

Chrome OS is partially developed under the open source Chromium OS project.

As with other open source projects, developers can modify the code from

Chromium OS and build their own versions, whereas Chrome OS code is

only supported by Google and its partners and only runs on hardware

designed for the purpose. Unlike Chromium OS, Chrome OS is automatically

updated to the latest version.

Chrome OS on Windows

On Windows 8 exceptions allow the default desktop web browser to offer a variant that can run inside its full-screen "Metro" shell and access features such as the Share charm, without necessarily needing to be written with Windows Runtime.

Chrome's "Windows 8 mode" was previously a tablet-optimized version of

the standard Chrome interface. In October 2013, the mode was changed on

Developer channel to offer a variant of the Chrome OS desktop.

Design

Early in the project, Google provided publicly many details of the Chrome OS's design goals and direction, although the company has not followed up with a technical description of the completed operating system.

User interface

Old Chrome-Chromium OS login screen

Design goals for Chrome OS's user interface included using minimal

screen space by combining applications and standard Web pages into a

single tab strip, rather than separating the two. Designers considered a

reduced window management scheme that would operate only in full-screen

mode. Secondary tasks would be handled with "panels": floating windows

that dock to the bottom of the screen for tasks like chat and music

players. Split screens were also under consideration for viewing two

pieces of content side-by-side. Chrome OS would follow the Chrome

browser's practice of leveraging HTML5's

offline modes, background processing, and notifications. Designers

proposed using search and pinned tabs as a way to quickly locate and

access applications.

New window manager and graphics engine

On

April 10, 2012, a new build of Chrome OS offered a choice between the

original full-screen window interface and overlapping, re-sizable

windows, such as found on Microsoft Windows and Apple's macOS.

The feature was implemented through the Ash window manager, which runs

atop the Aura hardware-accelerated graphics engine. The April 2012

upgrade also included the ability to display smaller, overlapping

browser windows, each with its own translucent tabs, browser tabs that

can be "torn" and dragged to new positions or merged with another tab

strip, and a mouse-enabled shortcut list across the bottom of the

screen. One icon on the task bar shows a list of installed applications

and bookmarks. Writing in CNET, Stephen Shankland argued that with

overlapping windows, "Google is anchoring itself into the past" as both

iOS and Microsoft's Metro

interface are largely or entirely full-screen. Even so, "Chrome OS

already is different enough that it's best to preserve any familiarity

that can be preserved".

Printing

Google Cloud Print

is a Google service that helps any application on any device to print

on supported printers. While the cloud provides virtually any connected

device with information access, the task of "developing and maintaining

print subsystems for every combination of hardware and operating

system—from desktops to netbooks to mobile devices—simply isn't

feasible." The cloud service requires installation of a piece of software called proxy,

as part of the Chrome OS. The proxy registers the printer with the

service, manages the print jobs, provides the printer driver

functionality, and gives status alerts for each job.

In 2016, Google included "Native CUPS

Support" in Chrome OS as an experimental feature that may eventually

become an official feature. With CUPS support turned on, it becomes

possible to use most USB printers even if they do not support Google

Cloud Print.

Link handling

Chrome OS

was designed with the intention of storing user documents and files on

remote servers. Both Chrome OS and the Chrome browser may introduce

difficulties to end users when handling specific file types offline; for

example, when opening an image or document residing on a local storage

device, it may be unclear whether and which specific Web application

should be automatically opened for viewing, or the handling should be

performed by a traditional application acting as a preview utility.

Matthew Papakipos, Chrome OS engineering director, noted in 2010 that

Windows developers have faced the same fundamental problem: "Quicktime

is fighting with Windows Media Player, which is fighting with Chrome."

Release channels and updates

Chrome

OS uses the same release system as Google Chrome: there are three

distinct channels: Stable, Beta, and Developer preview (called the "Dev"

channel). The stable channel is updated with features and fixes that

have been thoroughly tested in the Beta channel, and the Beta channel is

updated approximately once a month with stable and complete features

from the Developer channel. New ideas get tested in the Developer

channel, which can be very unstable at times. A fourth canary

channel was confirmed to exist by Google Developer Francois Beaufort

and hacker Kenny Strawn, by entering the Chrome OS shell in developer

mode, typing the command shell to access the bash shell, and finally entering the command update_engine_client -channel canary-channel -update.

It is possible to return to verified boot mode after entering the

canary channel, but the channel updater disappears and the only way to

return to another channel is using the "powerwash" factory reset.

Reception

At its debut, Chrome OS was viewed as a competitor to Microsoft, both directly to Microsoft Windows and indirectly the company's word processing and spreadsheet applications—the latter through Chrome OS's reliance on cloud computing.

But Chrome OS engineering director Matthew Papakipos argued that the

two operating systems would not fully overlap in functionality because

Chrome OS is intended for netbooks, which lack the computational power

to run a resource-intensive program like Adobe Photoshop.

Some observers claimed that other operating systems already

filled the niche that Chrome OS was aiming for, with the added advantage

of supporting native applications in addition to a browser. Tony

Bradley of PC World wrote in November 2009:

| “ | We can already do most, if not all, of what Chrome OS promises to deliver. Using a Windows 7 or Linux-based netbook, users can simply not install anything but a web browser and connect to the vast array of Google products and other web-based services and applications. Netbooks have been successful at capturing the low-end PC market, and they provide a web-centric computing experience today. I am not sure why we should get excited that a year from now we'll be able to do the same thing, but locked into doing it from the fourth-place web browser. | ” |

After this 2009 statement Chrome browser rose to become the number one browser used worldwide.

By 2016, Chromebooks had become the most popular computer in the US K–12 education market.

Relationship to Android

Google's offering of two open source operating systems, Android and Chrome OS, has drawn some criticism despite the similarity between this situation and that of Apple Inc's two operating systems, macOS and iOS. Steve Ballmer, Microsoft CEO at the time, accused Google of not being able to make up its mind. Steven Levy wrote that "the dissonance between the two systems was apparent" at Google I/O 2011. The event featured a daily press conference in which each team leader, Android's Andy Rubin and Chrome's Sundar Pichai, "unconvincingly tried to explain why the systems weren't competitive." Google co-founder Sergey Brin

addressed the question by saying that owning two promising operating

systems was "a problem that most companies would love to face". Brin suggested that the two operating systems "will likely converge over time."

The speculation over convergence increased in March 2013 when Chrome OS

chief Pichai replaced Rubin as the senior vice president in charge of

Android, thereby putting Pichai in charge of both.

The relationship between Android and Chrome OS became more

substantial at Google I/O 2014, where developers demonstrated native

Android software running on Chrome OS through a Native Client based runtime.

In October 2015, The Wall Street Journal reported that Chrome OS would

be folded into Android so that a single OS would result by 2017. The

resulting OS will be Android, but it will be expanded to run on laptops.

Google responded that while the company has "been working on ways to

bring together the best of both operating systems, there's no plan to

phase out Chrome OS."