Sikhism is based on the spiritual teachings of Guru Nanak, the first Guru (1469–1539), and the nine Sikh gurus that succeeded him. The Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, named the Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib as his successor, terminating the line of human Gurus and making the scripture the eternal, religious spiritual guide for Sikhs. Sikhism rejects claims that any particular religious tradition has a monopoly on Absolute Truth.

The Sikh scripture opens with Ik Onkar (ੴ), its Mul Mantar and fundamental prayer about One Supreme Being (God). Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as a means to feel God's presence. It teaches followers to transform the "Five Thieves" (lust, rage, greed, attachment, and ego). Hand in hand, secular life is considered to be intertwined with the spiritual life. Guru Nanak taught that living an "active, creative, and practical life" of "truthfulness, fidelity, self-control and purity" is above the metaphysical truth, and that the ideal man is one who "establishes union with God, knows His Will, and carries out that Will". Guru Hargobind, the sixth Sikh Guru, established the political/temporal (Miri) and spiritual (Piri) realms to be mutually coexistent.

Sikhism evolved in times of religious persecution. Two of the Sikh gurus – Guru Arjan (1563–1605) and Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675) – were tortured and executed by the Mughal rulers after they refused to convert to Islam. The persecution of Sikhs triggered the founding of the Khalsa as an order to protect the freedom of conscience and religion, with qualities of a "Sant-Sipāhī" – a saint-soldier. The Khalsa was founded by the last Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh.

Sikh terminology

The majority of Sikh scriptures were originally written in the Gurmukhī alphabet, a script standardised by Guru Angad out of Laṇḍā scripts used in North India.

Adherents of Sikhism are known as Sikhs, which means students or

disciples of the Guru. The anglicised word 'Sikhism' is derived from the

Punjabi verb Sikhi, with roots in Sikhana (to learn), and Sikhi connotes the "temporal path of learning".

Philosophy and teachings

Guru Nanak was the founder of the religion of Sikhism.

Sikh defined (SGPC):

Any human being who faithfully believes in

i. One Immortal Being,

ii. Ten Gurus, from Guru Nanak Sahib to Guru Gobind Singh Sahib,

iii. The Guru Granth Sahib,

iv. The utterances and teachings of the ten Gurus and

v. the baptism bequeathed by the tenth Guru, and who does not owe allegiance to any other religion, is a Sikh.

The basis of Sikhism lies in the teachings of Guru Nanak and his successors. Many sources call Sikhism a monotheistic religion, while others call it a monistic and panentheistic religion.

According to Eleanor Nesbitt, English renderings of Sikhism as a

monotheistic religion "tend misleadingly to reinforce a Semitic

understanding of monotheism, rather than Guru Nanak's mystical awareness

of the one that is expressed through the many. However, what is not in

doubt is the emphasis on 'one'".

In Sikhism, the concept of "God" is Waheguru considered Nirankar (shapeless), akal (timeless), and Alakh Niranjan (invisible). The Sikh scripture begins with Ik Onkar (ੴ), which refers to the "formless one", and understood in the Sikh tradition as monotheistic unity of God. Sikhism is classified as an Indian religion along with Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism, given its geographical origin and its sharing some concepts with them.

Sikh ethics emphasize the congruence between spiritual

development and everyday moral conduct. Its founder Guru Nanak

summarized this perspective with "Truth is the highest virtue, but

higher still is truthful living".

Concept of life

God in Sikhism is known as Ik Onkar, the One Supreme Reality or the all-pervading spirit (which is taken to mean God). This spirit has no gender in Sikhism, though translations may present it as masculine. It is also Akaal Purkh (beyond time and space) and Nirankar (without form). In addition, Nanak wrote that there are many worlds on which it has created life.

The traditional Mul Mantar goes from Ik Oankar until Nanak Hosee Bhee Sach. The opening line of the Guru Granth Sahib and each subsequent raga, mentions Ik Oankar (translated by Pashaura Singh):

ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ॥

Transliteration: ikk ōankār sat(i)-nām(u) karatā purakh(u) nirabha'u niravair(u) akāl(a) mūrat(i) ajūnī saibhan gur(a) prasād(i). "There is one supreme being, the eternal reality, the creator, without fear and devoid of enmity, immortal, never incarnated, self-existent, known by grace through the true Guru."

Worldly illusion

Māyā,

defined as a temporary illusion or "unreality", is one of the core

deviations from the pursuit of God and salvation: where worldly

attractions which give only illusory temporary satisfaction and pain

which distract the process of the devotion of God. However, Nanak

emphasised māyā as not a reference to the unreality of the world, but of

its values. In Sikhism, the influences of ego, anger, greed, attachment, and lust, known as the Five Thieves, are believed to be particularly distracting and hurtful. Sikhs believe the world is currently in a state of Kali Yuga (Age of Darkness) because the world is led astray by the love of and attachment to Maya.

The fate of people vulnerable to the Five Thieves ('Pānj Chor'), is

separation from God, and the situation may be remedied only after

intensive and relentless devotion.

Timeless truth

An Akali-Nihung Sikh Warrior at Harmandir Sahib, also called the Golden Temple

According to Guru Nanak the supreme purpose of human life is to reconnect with Akal (The Timeless One), however, egotism is the biggest barrier in doing this. Using the Guru's teaching remembrance of nām (the divine Word or the Name of the Lord) leads to the end of egotism. Guru Nanak designated the word 'guru' (meaning teacher) to mean the voice of "the spirit": the source of knowledge and the guide to salvation. As Ik Onkar is universally immanent, guru is indistinguishable from "Akal" and are one and the same. One connects with guru only with accumulation of selfless search of truth.

Ultimately the seeker realises that it is the consciousness within the

body which is seeker/follower of the Word that is the true guru. The human body is just a means to achieve the reunion with Truth.

Once truth starts to shine in a person's heart, the essence of current

and past holy books of all religions is understood by the person.

Liberation

Guru Nanak's teachings are founded not on a final destination of heaven or hell but on a spiritual union with the Akal which results in salvation or Jivanmukti (liberation whilst alive), a concept also found in Hinduism. Guru Gobind Singh makes it clear that human birth is obtained with great fortune, therefore one needs to be able to make the most of this life.

Sikhs believe in reincarnation and karma concepts found in Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. However, in Sikhism both karma and liberation "is modified by the concept of God's grace" (nadar, mehar, kirpa, karam etc.). Guru Nanak states "The body takes birth because of karma, but salvation is attained through grace". To get closer to God: Sikhs avoid the evils of Maya, keep the everlasting truth in mind, practice Shabad Kirtan, meditate on Naam, and serve humanity. Sikhs believe that being in the company of the Satsang or Sadh Sangat is one of the key ways to achieve liberation from the cycles of reincarnation.

Power and devotion (Shakti and Bhakti)

Sikhism was influenced by the Bhakti movement, but it was not simply an extension of Bhakti. Sikhism, for instance, disagreed with some views of Bhakti saints Kabir and Ravidas.

Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru and the founder of Sikhism, was a Bhakti saint. He taught, states Jon Mayled, that the most important form of worship is Bhakti. Guru Arjan, in his Sukhmani Sahib, recommended the true religion is one of loving devotion to God. The Sikh scripture Guru Granth Sahib includes suggestions on how a Sikh should perform constant Bhakti. Some scholars call Sikhism a Bhakti sect of Indian traditions, adding that it emphasises "nirguni Bhakti", that is loving devotion to a divine without qualities or physical form. However, Sikhism also accepts the concept of saguni, that is a divine with qualities and form.

While Western scholarship generally places Sikhism as arising primarily

within a Hindu Bhakti movement milieu while recognizing some Sufi

Islamic influences, Indian Sikh scholars disagree and state that Sikhism transcended the environment it emerged from.

Some Sikh sects outside the Punjab-region of India, such as those found in Maharashtra and Bihar, practice Aarti with lamps during bhakti in a Sikh Gurdwara. But, most Sikh Gurdwaras forbid the ceremonial use of lamps (aarti) during their bhakti practices.

While emphasizing Bhakti, the Sikh Gurus also taught that the spiritual life and secular householder life are intertwined.

In Sikh worldview, the everyday world is part of the Infinite Reality,

increased spiritual awareness leads to increased and vibrant

participation in the everyday world.

Guru Nanak, states Sonali Marwaha, described living an "active,

creative, and practical life" of "truthfulness, fidelity, self-control

and purity" as being higher than the metaphysical truth.

The 6th Sikh Guru, Guru Hargobind, after Guru Arjan martyrdom and faced with oppression by the Islamic Mughal Empire, affirmed the philosophy that the political/temporal (Miri) and spiritual (Piri) realms are mutually coexistent. According to the 9th Sikh Guru, Tegh Bahadur, the ideal Sikh should have both Shakti (power that resides in the temporal), and Bhakti (spiritual meditative qualities). This was developed into the concept of the Saint Soldier by the 10th Sikh Guru, Gobind Singh.

The concept of man as elaborated by Guru Nanak,

states Arvind-pal Singh Mandair, refines and negates the "monotheistic

concept of self/God", and "monotheism becomes almost redundant in the

movement and crossings of love".

The goal of man, taught the Sikh Gurus, is to end all dualities of

"self and other, I and not-I", attain the "attendant balance of

separation-fusion, self-other, action-inaction, attachment-detachment,

in the course of daily life".

Singing and music

Sikhs refer to the hymns of the Gurus as Gurbani (The Guru's word). Shabad Kirtan

is the singing of Gurbani. The entire verses of Guru Granth Sahib are

written in a form of poetry and rhyme to be recited in thirty one Ragas

of the Classical Indian Music as specified. However, the exponents of

these are rarely to be found amongst the Sikhs who are conversant with

all the Ragas in the Guru Granth Sahib. Guru Nanak started the Shabad

Kirtan tradition and taught that listening to kirtan is a powerful way

to achieve tranquility while meditating; Singing of the glories of the

Supreme Timeless One (God) with devotion is the most effective way to

come in communion with the Supreme Timeless One. The three morning prayers for Sikhs consist of Japji Sahib, Jaap Sahib and Tav-Prasad Savaiye. Baptised Sikhs – Amritdharis, rise early and meditate and then recite all the Five Banis of Nitnem before breakfast.

Remembrance of the divine name

A key practice by Sikhs is remembrance of the Divine Name Vaheguru (Naam – the Name of the Lord). This contemplation is done through Nām Japna (repetition of the divine name) or Naam Simran (remembrance of the divine Name through recitation).

The verbal repetition of the name of God or a sacred syllable has been

an ancient established practice in religious traditions in India,

however, Sikhism developed Naam-simran as an important Bhakti practice. Guru Nanak's ideal is the total exposure of one's being to the divine Name and a total conforming to Dharma or the "Divine Order". Nanak described the result of the disciplined application of nām simraṇ as a "growing towards and into God" through a gradual process of five stages. The last of these is sach khaṇḍ (The Realm of Truth) – the final union of the spirit with God.

Service and action

The Sikh Gurus taught that by constantly remembering the divine name (naam simran) and through selfless service, or sēvā, the devotee overcomes egoism (Haumai). This, it states, is the primary root of five evil impulses and the cycle of rebirth.

Service in Sikhism takes three forms: "Tan" – physical service;

"Man" – mental service (such as studying to help others); and "Dhan" –

material service. Sikhism stresses kirat karō: that is "honest work". Sikh teachings also stress the concept of sharing, or vaṇḍ chakkō, giving to the needy for the benefit of the community.

Justice and equality

Sikhism regards God as the true king, the king of all kings, the one who dispenses justice through the law of karma, a retributive model and divine grace.

The term for justice in the Sikh tradition is "Niau". It is related to the term "dharam" which in Sikhism connotes 'moral order' and righteousness. According to the Tenth Sikh Guru Guru Gobind Singh,

states Pashaura Singh – a professor of Sikh Studies, "one must first

try all the peaceful means of negotiation in the pursuit of justice" and

if these fail then it is legitimate to "draw the sword in defense of

righteousness".

Sikhism considers "an attack on dharam is an attack on justice, on

righteousness, and on the moral order generally" and the dharam "must be

defended at all costs".

The divine name is its antidote for all pain and vices. Forgiveness is

taught as a virtue in Sikhism, yet it also teaches its faithful to shun

those with evil intentions and to pick up the sword to fight injustice

and religious persecution.

Sikhism does not differentiate religious obligations by gender.

God in Sikhism has no gender, and the Sikh scripture does not

discriminate against the woman, nor bar her from any roles. Women in Sikhism have led battles and issued hukamnamas.

Ten gurus and authority

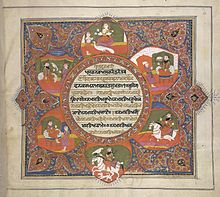

A rare Tanjore-style painting from the late 19th century depicting the ten Sikh Gurus with Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana

The term guru comes from the Sanskrit gurū, meaning teacher, guide, or mentor. The traditions and philosophy of Sikhism were established by ten gurus from 1469 to 1708.

Each guru added to and reinforced the message taught by the previous,

resulting in the creation of the Sikh religion. Guru Nanak was the first

guru and appointed a disciple as successor. Guru Gobind Singh

was the final guru in human form. Before his death, Guru Gobind Singh

decreed in 1708, that the Gurū Granth Sāhib would be the final and

perpetual guru of the Sikhs.

Guru Nanak stated that his Guru is God who is the same from the beginning of time to the end of time. Nanak claimed to be God's mouthpiece, God's slave and servant, but maintained that he was only a guide and teacher. Nanak stated that the human Guru is mortal, who is to be respected and loved but not worshipped. When Guru, or Satguru (The true guru) is used in Gurbani it is often referring to the highest expression of truthfulness – God.

Guru Angad

succeeded Guru Nanak. Later, an important phase in the development of

Sikhism came with the third successor, Guru Amar Das. Guru Nanak's

teachings emphasised the pursuit of salvation; Guru Amar Das began

building a cohesive community of followers with initiatives such as

sanctioning distinctive ceremonies for birth, marriage, and death. Amar

Das also established the manji (comparable to a diocese) system of clerical supervision.

Guru Amar Das's successor and son-in-law Guru Ram Das founded the city of Amritsar, which is home of the Harimandir Sahib and regarded widely as the holiest city for all Sikhs. Guru Arjan was arrested by Mughal authorities who were suspicious and hostile to the religious order he was developing.

His persecution and death inspired his successors to promote a military

and political organization of Sikh communities to defend themselves

against the attacks of Mughal forces.

The interior of the Akal Takht

The

Sikh gurus established a mechanism which allowed the Sikh religion to

react as a community to changing circumstances. The sixth guru, Guru Hargobind, was responsible for the creation of the concept of Akal Takht (throne of the timeless one), which serves as the supreme decision-making centre of Sikhism and sits opposite the Harmandir Sahib.

The Akal Takht is located in the city of Amritsar. The leader is

appointed by the Shiromani Gurdwara Pabandhak Committee (SPGC). The Sarbat Ḵẖālsā (a representative portion of the Khalsa Panth) historically gathers at the Akal Takht on special festivals such as Vaisakhi or Hola Mohalla and when there is a need to discuss matters that affect the entire Sikh nation. A gurmatā (literally, guru's intention)

is an order passed by the Sarbat Ḵẖālsā in the presence of the Gurū

Granth Sāhib. A gurmatā may only be passed on a subject that affects the

fundamental principles of Sikh religion; it is binding upon all Sikhs. The term hukamnāmā (literally, edict or royal order)

is often used interchangeably with the term gurmatā. However, a

hukamnāmā formally refers to a hymn from the Gurū Granth Sāhib which is a

given order to Sikhs.

| Chronology of the ten Sikh Gurus |

|---|

The word Guru in Sikhism also refers to Akal Purkh (God), and God and Guru are often synonymous in Gurbani (Sikh writings).

Scripture

There is one primary scripture for the Sikhs: the Gurū Granth Sāhib. It is sometimes synonymously referred to as the Ādi Granth. Chronologically, however, the Ādi Granth – literally, The First Volume, refers to the version of the scripture created by Guru Arjan in 1604. The Gurū Granth Sāhib is the final expanded version of the scripture compiled by Guru Gobind Singh. While the Guru Granth Sahib is an unquestioned scripture in Sikhism, another important religious text, the Dasam Granth, does not enjoy universal consensus, and is considered a secondary scripture by many Sikhs.

Adi Granth

The Ādi Granth was compiled primarily by Bhai Gurdas under the supervision of Guru Arjan between the years 1603 and 1604. It is written in the Gurmukhī script, which is a descendant of the Laṇḍā script used in the Punjab at that time. The Gurmukhī

script was standardised by Guru Angad, the second guru of the Sikhs,

for use in the Sikh scriptures and is thought to have been influenced by

the Śāradā and Devanāgarī

scripts. An authoritative scripture was created to protect the

integrity of hymns and teachings of the Sikh gurus, and thirteen Hindu

and two Muslim bhagats of the Bhakti movement sant tradition in medieval India. The thirteen Hindu bhagats whose teachings were entered into the text included Ramananda, Namdev, Pipa, Ravidas, Beni, Bhikhan, Dhanna, Jaidev, Parmanand, Sadhana, Sain, Sur, Trilochan, while the two Muslim bhagats were Kabir and Sufi saint Farid.

Guru Granth Sahib

Gurū Granth Sāhib – the primary scripture of Sikhism

The Guru Granth Sahib is the holy scripture of the Sikhs, and regarded as the living Guru.

Compilation

The

Guru Granth started as a volume of Guru Nanak's poetic compositions.

Prior to his death, he passed on his volume to Guru Angad (Guru

1539–1551). The final version of the Gurū Granth Sāhib was compiled by Guru Gobind Singh in 1678. It consists of the original Ādi Granth with the addition of Guru Tegh Bahadur's

hymns. The predominant bulk of Guru Granth Sahib is compositions by

seven Sikh Gurus – Guru Nanak, Guru Angad, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das,

Guru Arjan, Guru Teg Bahadur and Guru Gobind Singh. It also contains the

traditions and teachings of thirteen Hindu Bhakti movement sants (saints) such as Ramananda, Namdev among others, and two Muslim saints namely Kabir and the Sufi Sheikh Farid.

The text comprises 6,000 śabads (line compositions), which are poetically rendered and set to rhythmic ancient north Indian classical music. The bulk of the scripture is classified into thirty one rāgas, with each Granth rāga subdivided according to length and author. The hymns in the scripture are arranged primarily by the rāgas in which they are read.

Language and script

The main language used in the scripture is known as Sant Bhāṣā, a language related to both Punjabi and Hindi and used extensively across medieval northern India by proponents of popular devotional religion (bhakti). The text is printed in Gurumukhi script, believed to have been developed by Guru Angad, but it shares the Indo-European roots found in numerous regional languages of India.

Teachings

A group of Sikh musicians at the Golden Temple complex

The vision in the Guru Granth Sahib, states Torkel Brekke, is a society based on divine justice without oppression of any kind.

The Granth begins with the Mūl Mantra, an iconic verse which received Guru Nanak directly from Akal Purakh (God).

The traditional Mul Mantar goes from Ik Oankar until Nanak hosee bhee sach.

- Punjabi: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥

- ISO 15919 transliteration: Ika ōaṅkāra sati nāmu karatā purakhu nirabha'u niravairu akāla mūrati ajūnī saibhaṅ gura prasādi.

- Simplified transliteration: Ik ōaṅgkār sat nām kartā purkh nirbha'u nirvair akāl mūrat ajūnī saibhaṅ gur prasād.

- Translation: One God Exists, Truth by Name, Creative Power, Without Fear, Without Enmity, Timeless Form, Unborn, Self-Existent, By the Guru's Grace.

As Guru

The

Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, named the Sikh scripture Guru Granth

Sahib as his successor, terminating the line of human Gurus and making

the scripture the literal embodiment of the eternal, impersonal Guru,

where Gods/Gurus word serves as the spiritual guide for Sikhs.

- Punjabi: ਸੱਬ ਸਿੱਖਣ ਕੋ ਹੁਕਮ ਹੈ ਗੁਰੂ ਮਾਨਯੋ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ।

- Transliteration: Sabb sikkhaṇ kō hukam hai gurū mānyō granth.

- English: All Sikhs are commanded to take the Granth as Guru.

The Guru Granth Sahib is installed in Sikh Gurdwara (temple);

many Sikhs bow or prostrate before it on entering the temple. The Guru

Granth Sahib is installed every morning and put to bed at night in many Gurdwaras. The Granth is revered as eternal gurbānī and the spiritual authority.

The copies of the Guru Granth Sahib are not regarded as material objects, but as living subjects which are alive.

According to Myrvold, the Sikh scripture is treated with respect like a

living person, in a manner similar to the Gospel in early Christian

worship. Old copies of the Sikh scripture are not thrown away, rather

funerary services are performed.

In India the Guru Granth Sahib is even officially recognised by

the Supreme Court of India as a judicial person which can receive

donations and own land. Yet, some Sikhs also warn that, without true comprehension of the text, veneration for the text can lead to bibliolatry, with the concrete form of the teachings becoming the object of worship instead of the teachings themselves.

Relation to Hinduism and Islam

The Sikh scriptures use Hindu terminology, with references to the Vedas,

and the names of gods and goddesses in Hindu bhakti movement

traditions, such as Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, Parvati, Lakshmi, Saraswati,

Rama, Krishna, but not to worship. It also refers to the spiritual concepts in Hinduism (Ishvara, Bhagavan, Brahman) and the concept of God in Islam (Allah) to assert that these are just "alternate names for the Almighty One".

While the Guru Granth Sahib acknowledges the Vedas, Puranas and Quran, it does not imply a syncretic bridge between Hinduism and Islam, but emphasises focusing on nitnem banis like Japu (repeating mantra

of the divine Name of God – Vaheguru), instead of Muslim practices such

as circumcision or praying on a carpet, or Hindu rituals such as

wearing thread or praying in a river.

Dasam Granth

The

Dasam Granth is a Sikh scripture which contains texts attributed to

Guru Gobind Singh. The major narrative in the text is on Chaubis Avtar (24 Avatars of Hindu god Vishnu), Rudra, Brahma, the Hindu warrior goddess Chandi and a story of Rama in Bachittar Natak.

The Dasam Granth is a scripture of Sikhs which contains texts attributed to the Guru Gobind Singh. The Dasam Granth is important to a great number of Sikhs, however it does not have the same authority as the Guru Granth Sahib. Some compositions of the Dasam Granth like Jaap Sahib, (Amrit Savaiye), and Benti Chaupai are part of the daily prayers (Nitnem) for Sikhs. The Dasam Granth is largely versions of Hindu mythology from the Puranas, secular stories from a variety of sources called Charitro Pakhyan – tales to protect careless men from perils of lust.

Five versions of Dasam Granth exist, and the authenticity of the Dasam Granth

is amongst the most debated topics within Sikhism. The text played a

significant role in Sikh history, but in modern times parts of the text

have seen antipathy and discussion among Sikhs.

Janamsakhis

The Janamsākhīs (literally birth stories), are writings which profess to be biographies of Nanak. Although not scripture in the strictest sense, they provide a hagiographic

look at Nanak's life and the early start of Sikhism. There are several –

often contradictory and sometimes unreliable – Janamsākhīs and they are

not held in the same regard as other sources of scriptural knowledge.

Observances

The Darbar Sahib of a Gurdwara

Observant Sikhs adhere to long-standing practices and traditions to

strengthen and express their faith. The daily recitation of the divine

name of God Vaheguru and from memory of specific passages from the Gurū

Granth Sāhib, like the Japu (or Japjī, literally chant)

hymns is recommended immediately after rising and bathing. Baptized

Sikhs recite the five morning prayers, the evening and night prayer.

Family customs include both reading passages from the scripture and

attending the gurdwara (also gurduārā, meaning the doorway to God; sometimes transliterated as gurudwara).

There are many gurdwaras prominently constructed and maintained across

India, as well as in almost every nation where Sikhs reside. Gurdwaras

are open to all, regardless of religion, background, caste, or race.

Worship in a gurdwara consists chiefly of singing of passages

from the scripture. Sikhs will commonly enter the gurdwara, touch the

ground before the holy scripture with their foreheads. The recitation of

the eighteenth century ardās

is also customary for attending Sikhs. The ardās recalls past

sufferings and glories of the community, invoking divine grace for all

humanity.

The gurdwara is also the location for the historic Sikh practice of "Langar" or the community meal. All gurdwaras are open to anyone of any faith for a free meal, always vegetarian. People eat together, and the kitchen is maintained and serviced by Sikh community volunteers.

Sikh festivals/events

Guru Amar Das chose festivals for celebration by Sikhs like Vaisakhi, wherein he asked Sikhs to assemble and share the festivities as a community.

Vaisakhi is one of the most important festivals of Sikhs, while

other significant festivals commemorate the birth, lives of the Gurus

and Sikh martyrs. Historically, these festivals have been based on the

moon calendar Bikrami calendar. In 2003, the SGPC, the Sikh organisation in charge of upkeep of the historical gurdwaras of Punjab, adopted Nanakshahi calendar. The new calendar is highly controversial among Sikhs and is not universally accepted. Sikh festivals include the following:

- Vaisakhi

which includes Parades and Nagar Kirtan occurs on 13 April or 14 April.

Sikhs celebrate it because on this day which fell on 30 March 1699, the

tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, inaugurated the Khalsa, the 11th body of Guru Granth Sahib and leader of Sikhs till eternity.

- Nagar Kirtan involves the processional singing of holy hymns throughout a community. While practiced at any time, it is customary in the month of Visakhi (or Vaisakhi). Traditionally, the procession is led by the saffron-robed Panj Piare (the five beloved of the Guru), who are followed by the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy Sikh scripture, which is placed on a float.

Nagar Kirtan crowd listening to Kirtan at Yuba City.

- Band Chor Diwas has been another important Sikh festival in its history. In recent years, instead of Diwali, the post-2003 calendar released by SGPC has named it the Bandi Chhor divas. Sikhs celebrate Guru Hargobind's release from the Gwalior Fort, with several innocent Raja kings who were also imprisoned by Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1619. This day continues to be commemorated on the same day of Hindu festival of Diwali, with lights, fireworks and festivities.

- Hola Mohalla is a tradition started by Guru Gobind Singh. It starts the day after Sikhs celebrate Holi, sometimes referred to as Hola. Guru Gobind Singh modified Holi with a three-day Hola Mohalla extension festival of martial arts. The extension started the day after the Holi festival in Anandpur Sahib, where Sikh soldiers would train in mock battles, compete in horsemanship, athletics, archery and military exercises.

- Gurpurbs are celebrations or commemorations based on the lives of the Sikh gurus. They tend to be either birthdays or celebrations of Sikh martyrdom. All ten Gurus have Gurpurbs on the Nanakshahi calendar, but it is Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh who have a gurpurb that is widely celebrated in Gurdwaras and Sikh homes. The martyrdoms are also known as a Shaheedi Gurpurbs, which mark the martyrdom anniversary of Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur.

Ceremonies and customs

Sikh funeral procession, Mandi, Himachal Pradesh

Khalsa Sikhs have also supported and helped develop major pilgrimage

traditions to sacred sites such as Harmandir Sahib, Anandpur Sahib,

Fatehgarh Sahib, Patna Sahib, Hazur Nanded Sahib, Hemkund Sahib and

others. Sikh pilgrims and Sikhs of other sects customarily consider these as holy and a part of their Tirath. The Hola Mohalla around the festival of Holi, for example, is a ceremonial and customary gathering every year in Anandpur Sahib attracting over 100,000 Sikhs. Major Sikh temples feature a sarovar where some Sikhs take a customary dip. Some take home the sacred water of the tank particularly for sick friends and relatives, believing that the waters of such sacred sites have restorative powers and the ability to purify one's karma.

Upon a child's birth, the Guru Granth Sahib is opened at a random

point and the child is named using the first letter on the top left

hand corner of the left page. All boys are given the last name Singh, and all girls are given the last name Kaur (this was once a title which was conferred on an individual upon joining the Khalsa).

The Sikh marriage ritual includes the anand kāraj ceremony. The marriage ceremony is performed in front of the Guru Granth Sahib by a baptized Khalsa, Granthi of the Gurdwara.

The tradition of circling the Guru Granth Sahib and Anand Karaj among

Khalsa is practised since the fourth Guru, Guru Ram Das. Its official

recognition and adoption came in 1909, during the Singh Sabha Movement.

Upon death, the body of a Sikh is usually cremated. If this is

not possible, any respectful means of disposing the body may be

employed. The kīrtan sōhilā and ardās prayers are performed during the funeral ceremony (known as antim sanskār).

Baptism and the Khalsa

Khalsa

(meaning "Sovereign") is the collective name given by Guru Gobind Singh

to those Sikhs who have been initiated by taking part in a ceremony

called ammrit sañcār (nectar ceremony).

During this ceremony, sweetened water is stirred with a double-edged

sword while liturgical prayers are sung; it is offered to the initiating

Sikh, who ritually drinks it.

Many adherents of Sikhism do not undergo this ceremony, but still

adhere to some components of the faith and identify as Sikhs. The

initiated Sikh, considered reborn, is referred to as Khalsa Sikh, while

those who do not get baptised are referred to as Kesdhari or Sahajdhari

Sikhs.

The first time that this ceremony took place was on Vaisakhi, which fell on 30 March 1699 at Anandpur Sahib in Punjab. It was on that occasion that Gobind Singh baptised the Pañj Piārē

– the five beloved ones, who in turn baptised Guru Gobind Singh

himself. To males who initiated, the last name Singh, meaning "lion",

was given, while the last name Kaur, meaning "princess", was given to

baptised Sikh females.

Baptised Sikhs wear five items, called the Five Ks (in Punjabi known as pañj kakkē or pañj kakār), at all times. The five items are: kēs (uncut hair), kaṅghā (small wooden comb), kaṛā (circular steel or iron bracelet), kirpān (sword/dagger), and kacchera (special undergarment). The Five Ks have both practical and symbolic purposes.

History

Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the founder of Sikhism, was born in the village of Rāi Bhōi dī Talwandī, now called Nankana Sahib (in present-day Pakistan). His parents were Khatri Hindus. According to the hagiography Puratan Janamsakhi composed more than two centuries after his death and probably based on oral tradition, Nanak as a boy was fascinated by religion and spiritual matters, spending time with wandering ascetics and holy men.

His friend was Mardana, a Muslim. Together they would sing devotional

songs all night in front of the public, and bathe in the river in the

morning. One day, at the usual bath, Nanak went missing and his family

feared he had drowned. Three days later he returned home, and declared:

"There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" ("nā kōi hindū nā kōi musalmān").

Thereafter, Nanak started preaching his ideas that form the tenets of

Sikhism. In 1526, Guru Nanak at age 50, started a small commune in

Kartarpur and his disciples came to be known as Sikhs.

Although the exact account of his itinerary is disputed, hagiographic

accounts state he made five major journeys, spanning thousands of miles,

the first tour being east towards Bengal and Assam, the second south towards Andhra and Tamil Nadu, the third north to Kashmir, Ladakh, and Mount Sumeru in Tibet, and the fourth to Baghdad. In his last and final tour, he returned to the banks of the Ravi River to end his days.

There are two competing theories on Guru Nanak's teachings. One, according to Cole and Sambhi, is based on hagiographical Janamsakhis,

and states that Nanak's teachings and Sikhism were a revelation from

God, and not a social protest movement nor any attempt to reconcile

Hinduism and Islam in the 15th century. The other states, Nanak was a Guru.

According to Singha, "Sikhism does not subscribe to the theory of

incarnation or the concept of prophethood. But it has a pivotal concept

of Guru. He is not an incarnation of God, not even a prophet. He is an

illumined soul." The hagiographical Janamsakhis

were not written by Nanak, but by later followers without regard for

historical accuracy, and contain numerous legends and myths created to

show respect for Nanak.

The term revelation, clarify Cole and Sambhi, in Sikhism is not limited

to the teachings of Nanak, they include all Sikh Gurus, as well as the

words of past, present and future men and women, who possess divine

knowledge intuitively through meditation. The Sikh revelations include

the words of non-Sikh bhagats, some who lived and died before the birth of Nanak, and whose teachings are part of the Sikh scriptures.

The Adi Granth and successive Sikh Gurus repeatedly emphasised, states

Mandair, that Sikhism is "not about hearing voices from God, but it is

about changing the nature of the human mind, and anyone can achieve

direct experience and spiritual perfection at any time".

Scholars state that in its origins, Sikhism was influenced by the nirguni (formless God) tradition of Bhakti movement in medieval India. Nanak was raised in a Hindu family and belonged to the Bhakti Sant tradition. The roots of the Sikh tradition are, states Louis Fenech, perhaps in the Sant-tradition of India whose ideology grew to become the Bhakti tradition. Furthermore, adds Fenech, "Indic mythology permeates the Sikh sacred canon, the Guru Granth Sahib and the secondary canon, the Dasam Granth and adds delicate nuance and substance to the sacred symbolic universe of the Sikhs of today and of their past ancestors".

Historical influences

The development of Sikhism was influenced by the Bhakti movement; however, Sikhism was not simply an extension of the Bhakti movement. Sikhism developed while the region was being ruled by the Mughal Empire. Two of the Sikh gurus – Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur, after they refused to convert to Islam, were tortured and executed by the Mughal rulers. The Islamic era persecution of Sikhs triggered the founding of the Khalsa, as an order for freedom of conscience and religion. A Sikh is expected to embody the qualities of a "Sant-Sipāhī" – a saint-soldier.

Growth of Sikhism

Guru Nanak explaining Sikh teachings to Sadhus

In 1539, Guru Nanak chose his disciple Lahiṇā as a successor to the guruship rather than either of his sons. Lahiṇā was named Guru Angad and became the second guru of the Sikhs. Nanak conferred his choice at the town of Kartarpur on the banks of the river Ravi. Sri Chand, Guru Nanak's son was also a religious man, and continued his own commune of Sikhs. His followers came to be known as the Udasi Sikhs, the first parallel sect of Sikhism that formed in Sikh history.

The Udasis believe that the Guruship should have gone to Sri Chand,

since he was a man of pious habits in addition to being Nanak's son.

Guru Angad, before joining Guru Nanak's commune, worked as a pujari (priest) and religious teacher centered around Hindu goddess Durga. On Nanak's advice, Guru Angad moved from Kartarpur to Khadur, where his wife Khivi

and children were living, until he was able to bridge the divide

between his followers and the Udasis. Guru Angad continued the work

started by Guru Nanak and is widely credited for standardising the Gurmukhī script as used in the sacred scripture of the Sikhs.

Guru Amar Das became the third Sikh guru in 1552 at the age of 73. He adhered to the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism for much of his life, before joining the commune of Guru Angad. Goindval

became an important centre for Sikhism during the guruship of Guru Amar

Das. He was a reformer, and discouraged veiling of women's faces (a

Muslim custom) as well as sati (a Hindu custom). He encouraged the Kshatriya people to fight in order to protect people and for the sake of justice, stating this is Dharma. Guru Amar Das started the tradition of appointing manji (zones of religious administration with an appointed chief called sangatias), introduced the dasvandh ("the tenth" of income) system of revenue collection in the name of Guru and as pooled community religious resource, and the famed langar

tradition of Sikhism where anyone, without discrimination of any kind,

could get a free meal in a communal seating. The collection of revenue

from Sikhs through regional appointees helped Sikhism grow.

Guru Amar Das named his disciple and son-in-law Jēṭhā as the next Guru, who came to be known as Guru Ram Das.

The new Guru faced hostilities from the sons of Guru Amar Das and

therefore shifted his official base to lands identified by Guru Amar Das

as Guru-ka-Chak. He moved his commune of Sikhs there and the place then was called Ramdaspur, after him. This city grew and later became Amritsar – the holiest city of Sikhism. Guru Ram Das expanded the manji

organization for clerical appointments in Sikh temples, and for revenue

collections to theologically and economically support the Sikh

movement.

In 1581, Guru Arjan – youngest son of Guru Ram Das,

became the fifth guru of the Sikhs. The choice of successor, as

throughout most of the history of Sikh Guru successions, led to disputes

and internal divisions among the Sikhs. The elder son of Guru Ram Das named Prithi Chand

is remembered in the Sikh tradition as vehemently opposing Guru Arjan,

creating a faction Sikh community which the Sikhs following Guru Arjan

called as Minas (literally, "scoundrels").

Guru Arjan is remembered in the Sikh for many things. He built the first Harimandir Sahib (later to become the Golden Temple). He was a poet and created the first edition of Sikh sacred text known as the Ādi Granth (literally the first book)

and included the writings of the first five gurus and other enlightened

13 Hindu and 2 Muslim Sufi saints. In 1606, he was tortured and killed

by the Mughal emperor Jahangir, for refusing to convert to Islam. His martyrdom is considered a watershed event in the history of Sikhism.

Political advancement

After the martyrdom of Guru Arjan, his son Guru Hargobind

at age eleven became the sixth guru of the Sikhs and Sikhism

dramatically evolved to become a political movement in addition to being

religious. Guru Hargobind carried two swords, calling one spiritual and the other for temporal purpose (known as mīrī and pīrī in Sikhism).

According to the Sikh tradition, Guru Arjan asked his son Hargobind to

start a military tradition to protect the Sikh people and always keep

himself surrounded by armed Sikhs. The building of an armed Sikh militia

began with Guru Hargobind.

Guru Hargobind was soon arrested by the Mughals and kept in jail in

Gwalior. It is unclear how many years he served in prison, with

different texts stating it to be between 2 and 12 years. He married three women, built a fort to defend Ramdaspur and created a formal court called Akal Takht, now the highest Khalsa Sikh religious authority.

In 1644, Guru Hargobind named his grandson Har Rai as the guru. The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan attempted political means to undermine the Sikh tradition, by dividing and influencing the succession.

The Mughal ruler gave land grants to Dhir Mal, a grandson of Guru

Hargobind living in Kartarpur, and attempted to encourage Sikhs to

recognise Dhir Mal as the rightful successor to Guru Hargobind. Dhir Mal issued statements in favour of the Mughal state, and critical of his grandfather Guru Arjan.

Guru Hargobind rejected Dhir Mal, the later refused to give up the

original version of the Adi Granth he had, and the Sikh community was

divided.

Guru Har Rai is famed to have met Dara Shikoh during a time Dara

Shikoh and his younger brother Aurangzeb were in a bitter succession

fight. Aurangzeb summoned Guru Har Rai, who refused to go and sent his

elder son Ram Rai instead.

The emperor found a verse in the Sikh scripture insulting to Muslims,

and Ram Rai agreed it was a mistake then changed it. Ram Rai thus

pleased Aurangzeb, but displeased Guru Har Rai who excommunicated his

elder son. He nominated his younger son Guru Har Krishan to succeed him in 1661. Aurangzeb responded by granting Ram Rai a jagir (land grant). Ram Rai founded a town there and enjoyed Aurangzeb's patronage, the town came to be known as Dehradun, after Dehra referring to Ram Rai's shrine. Sikhs who followed Ram Rai came to be known as Ramraiya Sikhs.

Guru Har Krishan became the eighth Guru at the age of five, and died of

smallpox before reaching the age of eight. No hymns composed by these

three gurus are included in the Guru Granth Sahib.

Guru Tegh Bahadur, the uncle of Guru Har Krishan, became Guru in 1665. Tegh Bahadur resisted the forced conversions of Kashmiri Pandits and non-Muslims to Islam, and was publicly beheaded in 1675 on the orders of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in Delhi for refusing to convert to Islam. His beheading traumatized the Sikhs. His body was cremated in Delhi, the head was carried secretively by Sikhs and cremated in Anandpur. He was succeeded by his son, Gobind Rai who militarised his followers by creating the Khalsa in 1699, and baptising the Pañj Piārē. From then on, he was known as Guru Gobind Singh, and Sikh identity was redefined into a political force resisting religious persecution.

Sikh confederacy and the rise of the Khalsa

Guru Gobind Singh inaugurated the Khalsa (the collective body of all initiated Sikhs)

as the Sikh temporal authority in the year 1699. It created a community

that combines its spiritual purpose and goals with political and

military duties. Shortly before his death, Guru Gobind Singh proclaimed the Gurū Granth Sāhib (the Sikh Holy Scripture) to be the ultimate spiritual authority for the Sikhs.

Some bodyguard of Maharaja Ranjit Singh at the Sikh capital, Lahore, Punjab

The Sikh Khalsa's rise to power began in the 17th century during a

time of growing militancy against Mughal rule. The creation of a Sikh Empire began when Guru Gobind Singh sent a Sikh general, Banda Singh Bahadur, to fight the Mughal rulers of India and those who had committed atrocities against Pir Buddhu Shah.

Banda Singh advanced his army towards the main Muslim Mughal city of

Sirhind and, following the instructions of the guru, punished all the

culprits. Soon after the invasion of Sirhind, while resting in his

chamber after the Rehras prayer Guru Gobind Singh was stabbed by a Pathan assassin hired by Mughals.

Gobind Singh killed the attacker with his sword. Though a European

surgeon stitched the Guru's wound, the wound re-opened as the Guru

tugged at a hard strong bow after a few days, causing profuse bleeding

that led to Gobind Singh's death.

After the Guru's death, Baba Banda Singh Bahadur became the commander-in-chief of the Khalsa. He organised the civilian rebellion and abolished or halted the Zamindari system in time he was active and gave the farmers proprietorship of their own land. Banda Singh was executed by the emperor Farrukh Siyar after refusing the offer of a pardon if he converted to Islam. The confederacy of Sikh warrior bands known as misls emerged, but these fought between themselves. Ranjit Singh achieved a series of military victories and created a Sikh Empire in 1799.

The Sikh empire had its capital in Lahore, spread over almost 200,000 square miles (520,000 square kilometres) comprising what is now northwestern Indian subcontinent.

The Sikh Empire entered into a treaty with the colonial British powers,

with each side recognizing Sutlej River as the line of control and

agreeing not to invade the other side. Ranjit Singh's most lasting legacy was the restoration and expansion of the Harmandir Sahib, most revered Gurudwara of the Sikhs, with marble and gold, from which the popular name of the "Golden Temple" is derived.

After the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Sikh Empire fell into

disorder. Ranjit Singh had failed to establish a lasting structure for

Sikh government or stable succession, and the Sikh Empire rapidly

declined after his death. Factions divided the Sikhs, and led to Anglo

Sikh wars. The British easily defeated the confused and demoralised Khalsa forces, then disbanded them into destitution. The youngest son of Ranjit Singh named Duleep Singh ultimately succeeded, but he was arrested and exiled after the defeat of Sikh Khalsa.

Singh Sabha movement

The

last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire Duleep Singh converted to Christianity

in 1853, a controversial but influential event in Sikh history. Along

with his conversion, and after Sikh Empire had been dissolved and the

region made a part of the colonial British Empire, proselytising activities of Christians, Brahmo Samajis, Arya Samaj,

Muslim Anjuman-i-Islamia and Ahmadiyah sought to convert the Sikhs in

northwestern Indian subcontinent into their respective faiths. These developments launched the Singh Sabha Movement.

Sikhs sought to revive Sikhism in late 19th century. Its first

meeting was in the Golden Temple, Amritsar in 1873, and it was largely

launched by the Sanatan Sikhs, Gianis, priests, and granthis.

Shortly thereafter, Nihang Sikhs began influencing the movement,

followed by a sustained campaign by Tat Khalsa. The movement became a

struggle between Sanatan Sikhs and Tat Khalsa in defining and

interpreting Sikhism.

Sanatan Sikhs led by Khem Singh Bedi

– who claimed to be a direct descendant of Guru Nanak, Avtar Singh

Vahiria and others supported a more inclusive approach which considered

Sikhism as a reformed tradition of Hinduism, while Tat Khalsa campaigned

for an exclusive approach to the Sikh identity, disagreeing with

Sanatan Sikhs and seeking to modernize Sikhism. The Sikh Sabha movement expanded in north and northwest Indian subcontinent, leading to about a 100 Singh Sabhas.

By the early decades of the 20th century, the influence of Tat Khalsa

increased in interpreting the nature of Sikhism and their control over

the Sikh Gurdwaras.

Tat Khalsa introduced new practices such as the wedding ceremony in

1909 that centered around the Sikh Scripture replacing the earlier yagna fire, after removing the historic idols and the images of Sikh gurus from the Golden Temple

in 1905. They undertook a sustained campaign to redefine how Sikh

Gurdwaras looked and ran, as well as reinterpreted the Sikh scriptures

to purify the Sikh identity.

According to Oberoi, the Singh Sabha movement had a lasting impact on

Sikhism by "eradicating all forms of religious diversity within Sikhism"

and "establishing uniform norms of religious orthodoxy and orthopraxy".

Partition

Sikhs

participated and contributed to the decades-long Indian independence

movement from the colonial rule in the first half of the 20th century.

Ultimately when the British Empire recognized independent India, the

land was partitioned into Hindu majority India and Muslim majority

Pakistan (East and West) in 1947. This event, states Banga, was a

watershed event in Sikh history.

The Sikhs had historically lived in northwestern region of Indian

subcontinent on both sides of the partition line ("Radcliffe line").

According to Banga and other scholars, the Sikhs had strongly opposed

the Muslim League demands and saw it as "perpetuation of Muslim

domination" and anti-Sikh policies in what just a 100 years before was a

part of the Sikh Empire. During the discussions with the colonial

authorities, Tara Singh emerged as an important leader who campaigned to

prevent the partition and for the recognition of Sikhs as the third

community. In 1940, a few Sikhs such as the victims of Komagata Maru in Canada proposed the idea of Khalistan as a buffer state between Pakistan and India. These leaders, however, were largely ignored. Many other Sikh leaders supported the partition along religious and demographic lines.

When partition was announced, the newly created line divided the

Sikh population into two halves. The Sikhs suffered organized violence

and riots against them in West Pakistan, and Sikhs moved en masse to the

Indian side leaving behind their property and the sacred places of

Sikhism. This reprisals on Sikhs were not one sided, because as Sikhs

entered the Indian side, the Muslims in East Punjab experienced

reprisals and they moved to West Pakistan.

Before the partition, Sikhs constituted about 15% of the population in

West Punjab that became a part of Pakistan, the majority being Muslims

(55%). The Sikhs were the economic elite and wealthiest in West Punjab,

with them having the largest representation in West Punjab's

aristocracy, nearly 700 Gurdwaras and 400 educational institutions that

served the interests of the Sikhs.

Prior to the partition, there were a series of disputes between the

majority Muslims and minority Sikhs, such as on the matters of jhatka versus halal meat, the disputed ownership of Gurdwara Sahidganj

in Lahore which Muslims sought as a mosque and Sikhs as a Gurdwara, and

the insistence of the provincial Muslim government in switching from

Indian Gurmukhi script to Arabic-Persian Nastaliq script in schools.

During and after the Simla Conference in June 1945, headed by Lord

Wavell, the Sikh leaders initially expressed their desire to be

recognized as the third party, but ultimately relegated their demands

and sought a United India where Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims would live

together, under a Swiss style constitution. The Muslim League rejected

this approach, demanding that entire Punjab should be granted to

Pakistan.

The Sikh leaders then sought the partition instead, and Congress

Working Committee passed a resolution in support of partitioning Punjab

and Bengal.

Sikh Light Infantry personnel march past during the Republic day parade in New Delhi, India

Between March and August 1947, a series of riots, arson, plunder of

Sikh property, assassination of Sikh leaders, and killings in Jhelum

districts, Rawalpindi, Attock and other places made Tara Singh call the

situation in Punjab as "civil war", while Lord Mountbatten stated "civil

war preparations were going on". The riots had triggered the early

waves of migration in April, with some 20,000 people leaving northwest

Punjab and moving to Patiala.

In Rawalpindi, 40,000 people became homeless. The Sikh leaders made

desperate petitions, but all religious communities were suffering in the

political turmoil. Sikhs, states Banga, were "only 4 million out of a

total of 28 million in Punjab, and 6 million out of nearly 400 million

in India; they did not constitute the majority, not even in a single

district".

When the partition line was formally announced in August 1947,

the violence was unprecedented, with Sikhs being one of the most

affected religious community both in terms of deaths, as well as

property loss, injury, trauma and disruption.

Sikhs and Muslims were both victims and perpetrators of retaliatory

violence against each other. Estimates range between 200,000 and 2

million deaths of Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims.

There were numerous rapes of and mass suicides by Sikh women, they

being taken captives, their rescues and above all a mass exodus of Sikhs

from newly created Pakistan into newly created India. The partition

created the "largest foot convoy of refugees recorded in [human]

history, stretching over 100 kilometer long", states Banga, with nearly

300,000 people consisting of mostly "distraught, suffering, injured and

angry Sikhs". Sikh and Hindu refugees from Pakistan flooded into India,

Muslim refugees from India flooded into Pakistan, each into their new

homeland.

Khalistan

Sikhs in London protesting against the Indian government

The early 1980s witnessed some Sikh groups seeking an independent nation named Khalistan

carved out from India and Pakistan. The Golden Temple and Akal Takht

were occupied by various militant groups in 1982. These included the Dharam Yudh Morcha led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the Babbar Khalsa, the AISSF and the National Council of Khalistan. Between 1982 and 1983, there were Anandpur Resolution demand-related terrorist attacks against civilians in parts of India.

By late 1983, the Bhindranwale led group had begun to build bunkers and

observations posts in and around the Golden Temple, with militants

involved in weapons training. In June 1984, the then Prime Minister of India Indira Gandhi ordered Indian Army to begin Operation Blue Star against the militants.

The fierce engagement took place in the precincts of Darbar Sahib and

resulted in many deaths, including Bhindranwale, the destruction of the

Sikh Reference Library, which was considered a national treasure that

contained over a thousand rare manuscripts,

and destroyed Akal Takht. Numerous soldiers, civilians and militants

died in the cross fire. Within days of the Operation Bluestar, some

2,000 Sikh soldiers in India mutinied and attempted to reach Amritsar to

liberate the Golden Temple. Within six months, on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi's Sikh bodyguards assassinated her. The assassination triggered the 1984 anti-Sikh riots.

According to Donald Horowitz, while anti-Sikh riots led to much damage

and deaths, many serious provocations by militants also failed to

trigger ethnic violence in many cases throughout the 1980s. The Sikhs

and their neighbors, for most part, ignored attempts to provoke riots

and communal strife.

Sikh people

| State/UT | % Sikh | % Hindu | % Muslim | % Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punjab | 58% | 38.5% | 1.9% | Rest |

| Chandigarh | 13.1% | 80.8% | 4.9% | Rest |

| Haryana | 4.9% | 87.6% | 7.0% | Rest |

| Delhi | 3.4% | 80.7% | 12.9% | Rest |

| Uttarakhand | 2.3% | 83.0% | 14.0% | Rest |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 1.9% | 28.4% | 68.3% | Rest |

| Rajasthan | 1.3% | 88.5% | 9.1% | Rest |

| Himachal Pradesh | 1.2% | 95.2% | 2.2% | Rest |

Estimates state that Sikhism has some 25 million followers worldwide.

According to Pew Research, a religion demographics and research group

in Washington DC, "more than nine-in-ten Sikhs are in India, but there

are also sizable Sikh communities in the United Kingdom, the United

States and Canada."

Within India, the Sikh population is founded in every state and union

territory, but it is predominantly found the northwestern and northern

states. Only in the state of Punjab, Sikhs constitute a majority (58% of

the total, per 2011 census).

The states and union territories of India where Sikhs constitute more

than 1.5% of its population are Punjab, Chandigarh, Haryana, Delhi,

Uttarakhand and Jammu & Kashmir.

Sikhism was founded in northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent in what is now Pakistan. Some of the Gurus were born near Lahore

and in other parts of Pakistan. Prior to 1947, in British India,

millions of Sikhs lived in what later became Pakistan. During the

partition, Sikhs and Hindus left the newly created Muslim-majority

Pakistan and moved to Hindu-majority India, while Muslims in India left

and moved to Pakistan.

According to 2017 news reports, only about 20,000 Sikhs remain in

Pakistan and their population is dwindling (0.01% of its estimated 200

million population). The Sikhs in Pakistan, like others in the region,

have been "rocked by an Islamist insurgency for more than a decade".

Sikh sects

Sikh sects are sub-traditions within Sikhism that believe in an

alternate lineage of Gurus, or have a different interpretation of the

Sikh scriptures, or believe in following a living guru, or other

concepts that differ from the orthodox Khalsa Sikhs.

The major historic sects of Sikhism, states Harjot Oberoi, have

included Udasi, Nirmala, Nanakpanthi, Khalsa, Sahajdhari, Namdhari Kuka,

Nirankari and Sarvaria.

Namdhari Sikhs, also called the Kuka Sikhs are a sect of Sikhism known for their crisp white dress and horizontal pagari (turban). Above: Namdhari singer and musicians.

The early Sikh sects were Udasis and Minas founded by Sri Chand – the elder son of Guru Nanak, and Prithi Chand – the elder son of Guru Ram Das respectively, in parallel to the official succession of the Sikh Gurus. Later on Ramraiya sect grew in Dehradun with the patronage of Aurangzeb. Many splintered Sikh communities formed during the Mughal Empire

era. Some of these sects were financially and administratively

supported by the Mughal rulers in the hopes of gaining a more favorable

and compliant citizenry.

After the collapse of Mughal Empire, and particularly during the

rule of Ranjit Singh, Udasi Sikhs protected Sikh shrines, preserved the

Sikh scripture and rebuilt those that were desecrated or destroyed

during the Muslim–Sikh wars. However, Udasi Sikhs kept idols and images

inside these Sikh temples. In the 19th century, Namdharis and Nirankaris sects were formed in Sikhism, seeking to reform and return to what each believed was the pure form of Sikhism.

All these sects differ from Khalsa orthodox Sikhs in their

beliefs and practices, such as continuing to solemnize their weddings

around fire and being strictly vegetarian. Many accept the concept of living Gurus such as Guru Baba Dyal Singh.

The Nirankari sect though unorthodox was influential in shaping the

views of Tat Khalsa and the contemporary era Sikh beliefs and practices. Another significant Sikh sect of the 19th century was the Radhasoami movement in Punjab led by Baba Shiv Dyal. Other contemporary era Sikhs sects include the 3HO, formed in 1971, which exists outside India, particularly in North America and Europe.

Sikh castes

According to Surinder Jodhka, the state of Punjab with a Sikh majority has the "largest proportion of scheduled caste

population in India". Although decried by Sikhism, Sikhs have practiced

a caste system. The system, along with untouchability, has been more

common in rural parts of Punjab.The landowning dominant Sikh castes,

states Jodhka, "have not shed all their prejudices against the lower

castes or dalits;

while dalits would be allowed entry into the village gurdwaras they

would not be permitted to cook or serve langar." The Sikh dalits of

Punjab have tried to build their own gurdwara, other local level

institutions and sought better material circumstances and dignity.

According to Jodhka, due to economic mobility in contemporary Punjab,

castes no longer mean an inherited occupation nor are work relations

tied to a single location.

In 1953, the government of India acceded to the demands of the Sikh leader, Master Tara Singh, to include Sikh dalit castes in the list of scheduled castes. In the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee, 20 of the 140 seats are reserved for low-caste Sikhs.

Over 60% of Sikhs belong to the Jat caste, which is an agrarian caste. Despite being very small in numbers, the mercantile Khatri and Arora castes wield considerable influence within the Sikh community. Other common Sikh castes include Sainis, Rajputs, Ramgarhias (artisans), Ahluwalias (formerly brewers), Kambojs (rural caste), Labanas, Kumhars and the two Dalit castes, known in Sikh terminology as the Mazhabis (the Chuhras) and the Ramdasias (the Chamars).

Sikh diaspora

Sikhism is the fifth-largest amongst the major world religions, and one of the youngest. Worldwide, there are 25.8 million Sikhs, which makes up 0.39% of the world's population. Approximately 75% of Sikhs live in Punjab,

where they constitute over 50% of the state's population. Large

communities of Sikhs migrate to the neighboring states such as Indian

State of Haryana which is home to the second largest Sikh population in

India with 1.1 million Sikhs as per 2001 census, and large immigrant

communities of Sikhs can be found across India. However, Sikhs only

comprise about 2% of the Indian population.

Sikh migration to Canada began in the 19th century and led to the creation of significant Sikh communities, predominantly in South Vancouver, British Columbia, Surrey, British Columbia, and Brampton, Ontario. Today temples, newspapers, radio stations, and markets cater to these large, multi-generational Indo-Canadian groups. Sikh festivals such as Vaisakhi and Bandi Chhor are celebrated in those Canadian cities by the largest groups of followers in the world outside the Punjab.

Sikhs also migrated to East Africa, West Africa, the Middle East,

Southeast Asia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.

These communities developed as Sikhs migrated out of Punjab to fill in

gaps in imperial labour markets.

In the early twentieth century a significant community began to take

shape on the west coast of the United States. Smaller populations of

Sikhs are found within many countries in Western Europe, Mauritius,

Malaysia, Philippines, Fiji, Nepal, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq,

Singapore, United States, and many other countries.

Prohibitions in Sikhism

Some major prohibitions include:

- Cutting Hair: Cutting hair is forbidden in Sikhism for those who have taken the Amrit initiation ceremony. These Amritdhari or Khalsa Sikhs are required to keep unshorn hair.

- Intoxication: Consumption of alcohol, non-medicinal drugs, tobacco, and other intoxicants is forbidden in Sikhism according to the "Sikh Rahit Maryada". A Khalsa Amritdhari Sikh who consumes any intoxicant is considered patit lapsed, and may be readmitted into Khalsa only if re-baptised. In contrast, Nihangs of Sikh tradition who protect Sikh shrines wearing visible and ready weaponry along with their notable blue turbans, practice meditation with the aid of cannabis. Sehajdari Sikhs, in practice however, socially consume some alcohol; the prohibition on smoking is practiced almost universally by all Sikhs.

- Priestly Class: Sikhism does not have priests, but does have liturgical service which employs people for a salary to sing hymns (Kirtan), officiate an Ardās Puja or marriage, and perform services at a Gurdwara. Any Sikh can become a Granthi to look after the Guru Granth Sahib, and any Sikh is free to read from the Guru Granth Sahib.

- Eating Halal Meat: Both initiated and uninitiated Sikhs are strictly prohibited from eating meat from animals slaughtered by the halal method, known as Kutha meat, where the animal is killed by pronouncing the name of Allah and then exsanguination (via throat-cutting). According to Eleanor Nesbitt, on the general issue of vegetarianism versus non-vegetarianism, there is no definitive instruction in the Sikh code. In an Adi Granth verse, Guru Nanak responds to Hindu Brahmins who teach that it is polluting to eat meat by saying that as human beings, we are part of the chain of life, and even plants are living organisms. In other verses, Guru Nanak says that "Fools wrangle about eating meat", and calls out the Pandits by saying that "The eating of meat is considered sinful, but gratifying of greed is held good", in essence teaching that quelling the cruelty of the human mind is supreme rather than mere abstaining from eating meat. The ban on kutha meat (taken along with ban on sexual relations with Muslims and a ban on smoking – a habit common among 18th-century Indian Muslims), states Nesbitt, may have been meant for Sikhs to have a social separation from the Muslims due to the 17th- and 18th-century resistance of the Sikhs to the oppression of the Mughal and Afghan armies (both formed of Muslims). Amritdhari Sikhs, or those baptised with the Amrit, have been strict vegetarians, abstaining from all meat and eggs. Sikhs who eat meat seek the Jhatka method of producing meat believing it to cause less suffering to the animal. The uninitiated Sikhs too are not habitual meat-eaters by choice, and beef (cow meat) has been a traditional taboo. Typically meat is not served in community free meals such as langar.

- Adultery is forbidden.