The International Space Station on 23 May 2010 as seen from the departing Space Shuttle Atlantis during STS-132

| |

| |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| SATCAT no. | 25544 |

| Call sign | Alpha, Station |

| Crew | Fully crewed: 6 |

| Launch | 20 November 1998 |

| Launch pad | |

| Mass | ≈ 419,725 kg (925,335 lb) |

| Length | 72.8 m (239 ft) |

| Width | 108.5 m (356 ft) |

| Height | ≈ 20 m (66 ft) nadir–zenith, arrays forward–aft (27 November 2009) |

| Pressurised volume | 931.57 m3 (32,898 cu ft) (28 May 2016) |

| Atmospheric pressure | 101.3 kPa (29.9 inHg; 1.0 atm) |

| Perigee | 403 km (250 mi) AMSL |

| Apogee | 408 km (254 mi) AMSL |

| Orbital inclination | 51.64 degrees |

| Orbital speed | 7.66 km/s (27,600 km/h; 17,100 mph) |

| Orbital period | 92.68 minutes |

| Orbits per day | 15.54 |

| Orbit epoch | 28 November 2018, 14:37:49 UTC |

| Days in orbit | 20 years, 4 months, 9 days (29 March 2019) |

| Days occupied | 18 years, 4 months, 27 days (29 March 2019) |

| No. of orbits | 113,456 as of September 2018 |

| Orbital decay | 2 km/month |

| Statistics as of 9 March 2011 (unless noted otherwise) References: | |

| Configuration | |

Station elements as of June 2017

(exploded view) | |

The International Space Station (ISS) is a space station, or a habitable artificial satellite, in low Earth orbit. Its first component was launched into orbit in 1998, with the first long-term residents arriving in November 2000. It has been inhabited continuously since that date. The last pressurised module was fitted in 2011, and an experimental inflatable space habitat was added in 2016. The station is expected to operate until 2030. Development and assembly of the station continues, with several new elements scheduled for launch in 2019. The ISS is the largest human-made body in low Earth orbit and can often be seen with the naked eye from Earth. The ISS consists of pressurised habitation modules, structural trusses, solar arrays, radiators, docking ports, experiment bays and robotic arms. ISS components have been launched by Russian Proton and Soyuz rockets and American Space Shuttles.

The ISS serves as a microgravity and space environment research laboratory in which crew members conduct experiments in biology, human biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology, and other fields. The station is suited for the testing of spacecraft systems and equipment required for missions to the Moon and Mars. The ISS maintains an orbit with an altitude of between 330 and 435 km (205 and 270 mi) by means of reboost manoeuvres using the engines of the Zvezda module or visiting spacecraft. It circles the Earth in roughly 92 minutes and completes 15.5 orbits per day.

The ISS programme is a joint project between five participating space agencies: NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), JAXA (Japan), ESA (Europe), and CSA (Canada). The ownership and use of the space station is established by intergovernmental treaties and agreements. The station is divided into two sections, the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) and the United States Orbital Segment (USOS), which is shared by many nations. As of January 2018, operations of the American segment were funded until 2025. Roscosmos has endorsed the continued operation of ISS through 2024, but has proposed using elements of the Russian segment to construct a new Russian space station called OPSEK. In December 2018, the U.S. Senate extended ISS funding until 2030.

The ISS is the ninth space station to be inhabited by crews, following the Soviet and later Russian Salyut, Almaz, and Mir stations as well as Skylab from the US. The station has been continuously occupied for 18 years and 147 days since the arrival of Expedition 1 on 2 November 2000. This is the longest continuous human presence in low Earth orbit, having surpassed the previous record of 9 years and 357 days held by Mir. It has been visited by astronauts, cosmonauts and space tourists from 18 different nations. After the American Space Shuttle programme ended in 2011, Soyuz rockets became the only provider of transport for astronauts at the ISS.

The station is serviced by a variety of visiting spacecraft: the Russian Soyuz and Progress, the American Dragon and Cygnus, the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle, and formerly the American Space Shuttle and the European Automated Transfer Vehicle. The Dragon spacecraft allows the return of pressurised cargo to Earth (downmass), which is used for example to repatriate scientific experiments for further analysis. The Soyuz return capsule has minimal downmass capability next to the astronauts.

As of 14 March 2019, 236 people from 18 countries had visited the space station, many of them multiple times. The United States sent 149 people, Russia sent 47, nine were Japanese, eight were Canadian, five were Italian, four were French, three were German, and there were one each from Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Purpose

According to the original Memorandum of Understanding between NASA and Rosaviakosmos, the International Space Station was intended to be a laboratory, observatory and factory in low Earth orbit. It was also planned to provide transportation, maintenance, and act as a staging base for possible future missions to the Moon, Mars and asteroids. In the 2010 United States National Space Policy, the ISS was given additional roles of serving commercial, diplomatic and educational purposes.Scientific research

Expedition 8 Commander and Science Officer Michael Foale conducts an inspection of the Microgravity Science Glovebox

Fisheye view of several labs

CubeSats are deployed by the NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer

The ISS provides a platform to conduct scientific research. Small unmanned spacecraft can provide platforms for zero gravity and exposure to space, but space stations offer a long-term environment where studies can be performed potentially for decades, combined with ready access by human researchers over periods that exceed the capabilities of manned spacecraft.

The ISS simplifies individual experiments by eliminating the need for separate rocket launches and research staff. The wide variety of research fields include astrobiology, astronomy, human research including space medicine and life sciences, physical sciences, materials science, space weather, and weather on Earth (meteorology). Scientists on Earth have access to the crew's data and can modify experiments or launch new ones, which are benefits generally unavailable on unmanned spacecraft. Crews fly expeditions of several months' duration, providing approximately 160-man-hours per week of labour with a crew of 6.

To detect dark matter and answer other fundamental questions about our universe, engineers and scientists from all over the world built the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), which NASA compares to the Hubble Space Telescope, and says could not be accommodated on a free flying satellite platform partly because of its power requirements and data bandwidth needs. On 3 April 2013, NASA scientists reported that hints of dark matter may have been detected by the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer. According to the scientists, "The first results from the space-borne Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer confirm an unexplained excess of high-energy positrons in Earth-bound cosmic rays."

The space environment is hostile to life. Unprotected presence in space is characterised by an intense radiation field (consisting primarily of protons and other subatomic charged particles from the solar wind, in addition to cosmic rays), high vacuum, extreme temperatures, and microgravity. Some simple forms of life called extremophiles, as well as small invertebrates called tardigrades can survive in this environment in an extremely dry state through desiccation.

Medical research improves knowledge about the effects of long-term space exposure on the human body, including muscle atrophy, bone loss, and fluid shift. This data will be used to determine whether lengthy human spaceflight and space colonisation are feasible. As of 2006, data on bone loss and muscular atrophy suggest that there would be a significant risk of fractures and movement problems if astronauts landed on a planet after a lengthy interplanetary cruise, such as the six-month interval required to travel to Mars. Medical studies are conducted aboard the ISS on behalf of the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI). Prominent among these is the Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity study in which astronauts perform ultrasound scans under the guidance of remote experts. The study considers the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions in space. Usually, there is no physician on board the ISS and diagnosis of medical conditions is a challenge. It is anticipated that remotely guided ultrasound scans will have application on Earth in emergency and rural care situations where access to a trained physician is difficult.

Free fall

Gravity at the altitude of the ISS is approximately 90% as strong as at Earth's surface, but objects in orbit are in a continuous state of freefall, resulting in an apparent state of weightlessness. This perceived weightlessness is disturbed by five separate effects:- Drag from the residual atmosphere; when the ISS enters the Earth's shadow, the main solar panels are rotated to minimise this aerodynamic drag, helping reduce orbital decay.

- Vibration from movements of mechanical systems and the crew.

- Actuation of the on-board attitude control moment gyroscopes.

- Thruster firings for attitude or orbital changes.

- Gravity-gradient effects, also known as tidal effects. Items at different locations within the ISS would, if not attached to the station, follow slightly different orbits. Being mechanically interconnected these items experience small forces that keep the station moving as a rigid body.

ISS crew member storing samples

A comparison between the combustion of a candle on Earth (left) and in a free fall environment, such as that found on the ISS (right)

Researchers are investigating the effect of the station's

near-weightless environment on the evolution, development, growth and

internal processes of plants and animals. In response to some of this

data, NASA wants to investigate microgravity's effects on the growth of three-dimensional, human-like tissues, and the unusual protein crystals that can be formed in space.

Investigating the physics of fluids in microgravity will provide

better models of the behaviour of fluids. Because fluids can be almost

completely combined in microgravity, physicists investigate fluids that

do not mix well on Earth. In addition, examining reactions that are

slowed by low gravity and low temperatures will improve our

understanding of superconductivity.

The study of materials science

is an important ISS research activity, with the objective of reaping

economic benefits through the improvement of techniques used on the

ground.

Other areas of interest include the effect of the low gravity

environment on combustion, through the study of the efficiency of

burning and control of emissions and pollutants. These findings may

improve current knowledge about energy production, and lead to economic

and environmental benefits. Future plans are for the researchers aboard

the ISS to examine aerosols, ozone, water vapour, and oxides in Earth's atmosphere, as well as cosmic rays, cosmic dust, antimatter, and dark matter in the universe.

Exploration

A 3D plan of the Russia-based MARS-500 complex, used for ground-based experiments which complement ISS-based preparations for a human mission to Mars

The ISS provides a location in the relative safety of Low Earth Orbit

to test spacecraft systems that will be required for long-duration

missions to the Moon and Mars.

This provides experience in operations, maintenance as well as repair

and replacement activities on-orbit, which will be essential skills in

operating spacecraft farther from Earth, mission risks can be reduced

and the capabilities of interplanetary spacecraft advanced. Referring to the MARS-500

experiment, ESA states that "Whereas the ISS is essential for answering

questions concerning the possible impact of weightlessness, radiation

and other space-specific factors, aspects such as the effect of

long-term isolation and confinement can be more appropriately addressed

via ground-based simulations".

Sergey Krasnov, the head of human space flight programmes for Russia's

space agency, Roscosmos, in 2011 suggested a "shorter version" of

MARS-500 may be carried out on the ISS.

In 2009, noting the value of the partnership framework itself,

Sergey Krasnov wrote, "When compared with partners acting separately,

partners developing complementary abilities and resources could give us

much more assurance of the success and safety of space exploration. The

ISS is helping further advance near-Earth space exploration and

realisation of prospective programmes of research and exploration of the

Solar system, including the Moon and Mars." A manned mission to Mars

may be a multinational effort involving space agencies and countries

outside the current ISS partnership. In 2010, ESA Director-General

Jean-Jacques Dordain stated his agency was ready to propose to the other

four partners that China, India and South Korea be invited to join the

ISS partnership. NASA chief Charlie Bolden stated in February 2011, "Any mission to Mars is likely to be a global effort". Currently, American legislation prevents NASA co-operation with China on space projects.

Education and cultural outreach

Japan's Kounotori 4 berthing

The ISS crew provides opportunities for students on Earth by running

student-developed experiments, making educational demonstrations,

allowing for student participation in classroom versions of ISS

experiments, and directly engaging students using radio, videolink and

email. ESA offers a wide range of free teaching materials that can be downloaded for use in classrooms.

In one lesson, students can navigate a 3-D model of the interior and

exterior of the ISS, and face spontaneous challenges to solve in real

time.

JAXA aims both to "Stimulate the curiosity of children,

cultivating their spirits, and encouraging their passion to pursue

craftsmanship", and to "Heighten the child's awareness of the importance

of life and their responsibilities in society."

Through a series of education guides, a deeper understanding of the

past and near-term future of manned space flight, as well as that of

Earth and life, will be learned.

In the JAXA Seeds in Space experiments, the mutation effects of

spaceflight on plant seeds aboard the ISS is explored. Students grow

sunflower seeds which flew on the ISS for about nine months as a start

to 'touch the Universe'. In the first phase of Kibō utilisation

from 2008 to mid-2010, researchers from more than a dozen Japanese

universities conducted experiments in diverse fields.

Original Jules Verne manuscripts displayed by crew inside Jules Verne ATV

Amateur Radio on the ISS

(ARISS) is a volunteer programme which encourages students worldwide to

pursue careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics

through amateur radio

communications opportunities with the ISS crew. ARISS is an

international working group, consisting of delegations from nine

countries including several countries in Europe as well as Japan,

Russia, Canada, and the United States. In areas where radio equipment

cannot be used, speakerphones connect students to ground stations which

then connect the calls to the station.

First Orbit is a feature-length documentary film about Vostok 1,

the first manned space flight around the Earth. By matching the orbit

of the International Space Station to that of Vostok 1 as closely as

possible, in terms of ground path and time of day, documentary filmmaker

Christopher Riley and ESA astronaut Paolo Nespoli were able to film the view that Yuri Gagarin

saw on his pioneering orbital space flight. This new footage was cut

together with the original Vostok 1 mission audio recordings sourced

from the Russian State Archive. Nespoli, during Expedition 26/27, filmed

the majority of the footage for this documentary film, and as a result

is credited as its director of photography. The film was streamed through the website firstorbit.org in a global YouTube premiere in 2011, under a free licence.

In May 2013, commander Chris Hadfield shot a music video of David Bowie's "Space Oddity" on board the station; the film was released on YouTube. It was the first music video ever to be filmed in space.

In November 2017, while participating in Expedition 52/53 on the

ISS, Paolo Nespoli made two recordings (one in English the other in his

native Italian) of his spoken voice, for use on Wikipedia articles. These were the first content made specifically for Wikipedia, in space.

Manufacturing

ISS module Node 2 manufacturing and processing in the SSPF

Since the International Space Station is a multi-national

collaborative project, the components for in-orbit assembly had to be

manufactured in various factories around the world. The U.S. Modules (Destiny,Tranquillity, Unity and Harmony) as well as the Integrated Truss Structure and solar arrays were fabricated at the Marshall Space Flight Center and the Michoud Assembly Facility, beginning in the mid 1990s. The modules were delivered to the Operations and Checkout Building, and the Space Station Processing Facility at Kennedy Space Center for final assembly and processing for launch. Steel and aluminium sections of the truss were part contracted by Alcoa and ArcelorMittal USA, along with Boeing.

Russian modules - Zarya and Zvezda for example, were manufactured at the Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center in Moscow. Zvezda was initially manufactured in 1985 as a component for Mir-2, but was never launched and instead became the ISS Service Module. The European Space Agency Columbus module was manufactured at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in the Netherlands, along with many other contractors throughout Europe.

The Japanese Experiment Module Kibo, was fabricated in various technology manufacturing facilities in Japan, at the NASDA (now JAXA) Tanegashima Space Center and the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science.

The Kibo module was flown by aircraft to the KSC Space Station

Processing Facility, along with the ESA Columbus laboratory for shuttle

launch on STS-124 and STS-122 respectively.

The Mobile Servicing System - consisting of the Canadarm-2 and the Dextre

grapple fixture, were manufactured at various factories in Canada and

the United States. The mobile base system - the connecting framework for

Canadarm-2 mounted on rails, was built by Northrop Grumman in Carpinteria, CA. The Canadarm-2 and Dextre was made by MDA Space Missions, a satellite and aerospace factory in Brampton Ontario, under contract by the Canadian Space Agency and NASA.

Assembly

ISS in 2000, with Z1 truss added

ISS in 2000, with P6 truss added

ISS in 2002, with S0 truss added

ISS in 2002, with S1 truss added

ISS in 2002, with P1 Truss added

ISS in 2006, with P3/P4 truss added

ISS in 2006, with P5 truss added

ISS in 2007, with S3/S4 truss added

ISS in 2007, with S5 truss added

ISS in 2007, with P6 truss relocated

ISS in 2009, with S6 truss added

The assembly of the International Space Station, a major endeavour in space architecture, began in November 1998. Russian modules launched and docked robotically, with the exception of Rassvet. All other modules were delivered by the Space Shuttle, which required installation by ISS and shuttle crewmembers using the Canadarm2 (SSRMS) and extra-vehicular activities (EVAs); as of 5 June 2011, they had added 159 components during more than 1,000 hours of EVA (see List of ISS spacewalks).

127 of these spacewalks originated from the station, and the remaining

32 were launched from the airlocks of docked Space Shuttles. The beta angle

of the station had to be considered at all times during construction,

as it directly affects how long during its orbit the station (and any

docked or docking spacecraft) is exposed to the sun; the Space Shuttle

would not perform optimally above a limit called the "beta cutoff". Many of the modules that launched on the Space Shuttle were integrated and tested on the ground at the Space Station Processing Facility to find and correct issues prior to launch.

The first module of the ISS, Zarya, was launched on 20 November 1998 on an autonomous Russian Proton rocket. It provided propulsion, attitude control, communications, electrical power, but lacked long-term life support functions. Two weeks later, a passive NASA module Unity was launched aboard Space Shuttle flight STS-88 and attached to Zarya by astronauts during EVAs. This module has two Pressurized Mating Adapters (PMAs), one connects permanently to Zarya, the other allows the Space Shuttle to dock to the space station. At that time, the Russian station Mir was still inhabited. The ISS remained unmanned for two years, while Mir was de-orbited. On 12 July 2000, Zvezda

was launched into orbit. Preprogrammed commands on board deployed its

solar arrays and communications antenna. It then became the passive

target for a rendezvous with Zarya and Unity: it maintained a station-keeping orbit while the Zarya-Unity vehicle performed the rendezvous and docking via ground control and the Russian automated rendezvous and docking system. Zarya's computer transferred control of the station to Zvezda's computer soon after docking. Zvezda added sleeping quarters, a toilet, kitchen, CO2

scrubbers, dehumidifier, oxygen generators, exercise equipment, plus

data, voice and television communications with mission control. This

enabled permanent habitation of the station.

The first resident crew, Expedition 1, arrived in November 2000 on Soyuz TM-31. At the end of the first day on the station, astronaut Bill Shepherd requested the use of the radio call sign "Alpha", which he and cosmonaut Krikalev preferred to the more cumbersome "International Space Station". The name "Alpha" had previously been used for the station in the early 1990s, and following the request, its use was authorised for the whole of Expedition 1. Shepherd had been advocating the use of a new name to project managers for some time. Referencing a naval tradition

in a pre-launch news conference he had said: "For thousands of years,

humans have been going to sea in ships. People have designed and built

these vessels, launched them with a good feeling that a name will bring

good fortune to the crew and success to their voyage." Yuri Semenov, the President of Russian Space Corporation Energia at the time, disapproved of the name "Alpha"; he felt that Mir was the first space station, and so he would have preferred the names "Beta" or "Mir 2" for the ISS.

Expedition 1 arrived midway between the flights of STS-92 and STS-97. These two Space Shuttle flights each added segments of the station's Integrated Truss Structure,

which provided the station with Ku-band communication for US

television, additional attitude support needed for the additional mass

of the USOS, and substantial solar arrays supplementing the station's existing 4 solar arrays.

Over the next two years, the station continued to expand. A Soyuz-U rocket delivered the Pirs docking compartment. The Space Shuttles Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour delivered the Destiny laboratory and Quest airlock, in addition to the station's main robot arm, the Canadarm2, and several more segments of the Integrated Truss Structure.

The expansion schedule was interrupted by the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003 and a resulting two-year hiatus in the Space Shuttle programme. The space shuttle was grounded until 2005 with STS-114 flown by Discovery.

Assembly resumed in 2006 with the arrival of STS-115 with Atlantis,

which delivered the station's second set of solar arrays. Several more

truss segments and a third set of arrays were delivered on STS-116, STS-117, and STS-118.

As a result of the major expansion of the station's power-generating

capabilities, more pressurised modules could be accommodated, and the Harmony node and Columbus European laboratory were added. These were soon followed by the first two components of Kibō. In March 2009, STS-119

completed the Integrated Truss Structure with the installation of the

fourth and final set of solar arrays. The final section of Kibō was delivered in July 2009 on STS-127, followed by the Russian Poisk module. The third node, Tranquility, was delivered in February 2010 during STS-130 by the Space Shuttle Endeavour, alongside the Cupola, followed in May 2010 by the penultimate Russian module, Rassvet. Rassvet was delivered by Space Shuttle Atlantis on STS-132 in exchange for the Russian Proton delivery of the Zarya module in 1998 which had been funded by the United States. The last pressurised module of the USOS, Leonardo, was brought to the station by Discovery on her final flight, STS-133, in February 2011. The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer was delivered by Endeavour on STS-134 the same year.

As of June 2011, the station consisted of 15 pressurised modules and the Integrated Truss Structure. Five modules are still to be launched, including the Nauka with the European Robotic Arm, the Uzlovoy Module, and two power modules called NEM-1 and NEM-2. As of August 2017, Russia's future primary research module Nauka

is set to launch in November 2019, along with the European Robotic Arm

which will be able to relocate itself to different parts of the Russian

modules of the station. After the Nauka module is attached, the

Uzlovoy Module will be attached to one of its docking ports. When

completed, the station will have a mass of more than 400 tonnes (440

short tons).

The gross mass of the station changes over time. The total launch

mass of the modules on orbit is about 417,289 kg (919,965 lb) (as of

3 September 2011).

The mass of experiments, spare parts, personal effects, crew,

foodstuff, clothing, propellants, water supplies, gas supplies, docked

spacecraft, and other items add to the total mass of the station.

Hydrogen gas is constantly vented overboard by the oxygen generators.

Structure

3-D model of the International Space Station (click to rotate)

Technical blueprint of components

The ISS is a third generation modular space station.

Modular stations can allow the mission to be changed over time and new

modules can be added or removed from the existing structure, allowing

greater flexibility.

Comparison

The ISS follows Salyut and Almaz series, Skylab, and Mir as the 11th space station launched, as the Genesis prototypes were never intended to be manned. Other examples of modular station projects include the Soviet/Russian Mir and the planned Russian OPSEK and Chinese space station. First generation space stations, such as early Salyuts and NASA's Skylab were not designed for re-supply. Generally, each crew had to depart the station to free the only docking port for the next crew to arrive, Skylab had more than one docking port but was not designed for resupply. Salyut 6 and 7 had more than one docking port and were designed to be resupplied routinely during crewed operation.

Pressurised modules

Zarya

Zarya as seen by Space Shuttle Endeavour during STS-88

Zarya (Russian: Заря́; lit. dawn), also known as the Functional Cargo Block

or FGB (from the Russian "Функционально-грузовой блок",

Funktsionalno-gruzovoy blok or ФГБ), was the first module of the

International Space Station to be launched. The FGB provided electrical

power, storage, propulsion, and guidance to the ISS during the initial

stage of assembly. With the launch and assembly in orbit of other

modules with more specialised functionality, Zarya is now primarily used for storage, both inside the pressurised section and in the externally mounted fuel tanks. Zarya is a descendant of the TKS spacecraft designed for the Soviet Salyut programme. The name Zarya

was given to the FGB because it signified the dawn of a new era of

international co-operation in space. Although it was built by a Russian

company, it is owned by the United States. Zarya weighs 19,300 kg (42,500 lb), is 12.55 m (41.2 ft) long and 4.1 m (13 ft) wide, discounting solar arrays.

Zarya was built from December 1994 to January 1998 at the Khrunichev State Research and Production Space Center (KhSC) in Moscow. The control system was developed by the Ukrainian Khartron corporation in Kharkiv.

Zarya was launched on 20 November 1998, on a Russian Proton rocket from Baikonur Cosmodrome Site 81 in Kazakhstan to a 400 km (250 mi) high orbit with a designed lifetime of at least 15 years. After Zarya reached orbit, STS-88 launched on 4 December 1998, to attach the Unity module.

Although only designed to fly autonomously for six to eight months, Zarya did so for almost two years because of delays with the Russian Service Module, Zvezda, which finally launched on 12 July 2000, and docked with Zarya on 26 July using the Russian Kurs docking system.

Unity

Unity as pictured by Space Shuttle Endeavour

Unity, or Node 1, is one of three nodes, or passive connecting modules, in the US Orbital Segment

of the station. It was the first US-built component of the Station to

be launched. The module is made of aluminium and cylindrical in shape,

with six berthing locations facilitating connections to other modules.

Essential space station resources such as fluids, environmental control

and life support systems, electrical and data systems are routed through

Unity to supply work and living areas of the station. More than

50,000 mechanical items, 216 lines to carry fluids and gases, and 121

internal and external electrical cables using six miles of wire were

installed in the Unity node. Prior to its launch, conical

Pressurized Mating Adapters (PMAs) were attached to the aft and forward

berthing mechanisms of Unity. Unity and the two mating

adapters together weighed about 11,600 kg (25,600 lb). The adapters

allow the docking systems used by the Space Shuttle and by Russian

modules to attach to the node's hatches and berthing mechanisms.

Unity was carried into orbit by Space Shuttle Endeavour in 1998 as the primary cargo of STS-88,

the first Space Shuttle mission dedicated to assembly of the station.

On 6 December 1998, the STS-88 crew mated the aft berthing port of Unity with the forward hatch of the already orbiting Zarya module.

Zvezda

Zvezda (Russian: Звезда́, meaning "star"), also known as DOS-8, Service Module or SM (Russian: СМ). Early in the station's life, Zvezda provided all of its critical systems.

It made the station permanently habitable for the first time, adding

life support for up to six crew and living quarters for two. Zvezda's DMS-R computer handles guidance, navigation and control for the entire space station. A second computer which performs the same functions will be installed in the Nauka module, FGB-2.

Initially built to be the core of the cancelled Mir-2 space station, the hull of Zvezda was completed in February 1985, with major internal equipment installed by October 1986. The module was launched by a Proton-K rocket from Site 81/23 at Baikonur, on 12 July 2000. Zvezda

is at the rear of the station according to its normal direction of

travel and orientation, and its engines may be used to boost the

station's orbit. Alternatively Russian and European spacecraft can dock

to Zvezda's aft port and use their engines to boost the station.

Destiny

Destiny laboratory interior in February 2001

Robotic equipment near the aft end of the module, being operated by Leland Melvin

Destiny,

also known as the U.S. Lab, is the primary research facility for United

States payloads aboard the ISS. In 2011, NASA chose the not-for-profit

group Center for the Advancement of Science in Space

(CASIS) to be the sole manager of all American science on the station

which does not relate to manned exploration. The module houses 24 International Standard Payload Racks, some of which are used for environmental systems and crew daily living equipment. Destiny also serves as the mounting point for the station's Truss Structure.

Quest

Quest airlock during installation in 2001

Quest is the only USOS airlock, and hosts spacewalks with both United States EMU and Russian Orlan spacesuits.

It consists of two segments: the equipment lock, which stores

spacesuits and equipment, and the crew lock, from which astronauts can

exit into space. This module has a separately controlled atmosphere.

Crew sleep in this module, breathing a low nitrogen mixture the night

before scheduled EVAs, to avoid decompression sickness (known as "the bends") in the low-pressure suits.

Pirs and Poisk

Pirs (Russian: Пирс, meaning "pier"), (Russian: Стыковочный отсек), "docking module", SO-1 or DC-1 (docking compartment), and Poisk (Russian: По́иск; lit. Search), also known as the Mini-Research Module 2 (MRM 2), Малый исследовательский модуль 2, or МИМ 2. Pirs and Poisk are Russian airlock modules, each having 2 identical hatches. An outward-opening hatch on the Mir

space station failed after it swung open too fast after unlatching,

because of a small amount of air pressure remaining in the airlock. A different entry was used, and the hatch was repaired. All EVA hatches on the ISS open inwards and are pressure-sealing. Pirs was used to store, service, and refurbish Russian Orlan suits

and provided contingency entry for crew using the slightly bulkier

American suits. The outermost docking ports on both airlocks allow

docking of Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, and the automatic transfer of

propellants to and from storage on the ROS.

Harmony

Harmony node in 2011

Tranquility node in 2011

Harmony,

also known as Node 2, is the second of the station's node modules and

the utility hub of the USOS. The module contains four racks that provide

electrical power, bus electronic data, and acts as a central connecting

point for several other components via its six Common Berthing

Mechanisms (CBMs). The European Columbus and Japanese Kibō

laboratories are permanently berthed to the starboard and port radial

ports respectively. The nadir and zenith ports can be used for docking

visiting spacecraft including HTV, Dragon, and Cygnus, with the nadir

port serving as the primary docking port. American Shuttle Orbiters

docked with the ISS via PMA-2, attached to the forward port.

Tranquility

Tranquility,

also known as Node 3, is the third and last of the station's US nodes,

it contains an additional life support system to recycle waste water for

crew use and supplements oxygen generation. Like the other US nodes, it

has six berthing mechanisms, five of which are currently in use. The

first one connects to the station's core via the Unity module, others host the Cupola, the PMA docking port #3, the Leonardo PMM and the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module. The final zenith port remains free.

Columbus

Columbus module in 2008

Columbus, the primary research facility for European payloads aboard the ISS, provides a generic laboratory as well as facilities specifically designed for biology, biomedical research and fluid physics.

Several mounting locations are affixed to the exterior of the module,

which provide power and data to external experiments such as the European Technology Exposure Facility (EuTEF), Solar Monitoring Observatory, Materials International Space Station Experiment, and Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space. A number of expansions are planned for the module to study quantum physics and cosmology.

ESA's development of technologies on all the main areas of life support

has been ongoing for more than 20 years and are/have been used in

modules such as Columbus and the ATV. The German Aerospace Center manages ground control operations for Columbus and the ATV is controlled from the French CNES Toulouse Space Center.

Kibō

Not large enough for crew using spacesuits, the airlock on Kibō has a sliding drawer for external experiments.

Kibō (Japanese: きぼう, "hope")

is a laboratory and the largest ISS module. It is used for research in

space medicine, biology, Earth observations, materials production,

biotechnology and communications, and has facilities for growing plants

and fish. During August 2011, the MAXI observatory mounted on Kibō,

which uses the ISS's orbital motion to image the whole sky in the X-ray

spectrum, detected for the first time the moment when a star was

swallowed by a black hole.

The laboratory contains 23 racks, including 10 experiment racks, and

has a dedicated airlock for experiments. In a 'shirt sleeves'

environment, crew attach an experiment to the sliding drawer within the

airlock, close the inner, and then open the outer hatch. By extending

the drawer and removing the experiment using the dedicated robotic arm,

payloads are placed on the external platform. The process can be

reversed and repeated quickly, allowing access to maintain external

experiments without the delays caused by EVAs.

A smaller pressurised module is attached to the top of Kibō, serving as a cargo bay. The dedicated Interorbital Communications System (ICS) allows large amounts of data to be beamed from Kibō's

ICS, first to the Japanese KODAMA satellite in geostationary orbit,

then to Japanese ground stations. When a direct communication link is

used, contact time between the ISS and a ground station is limited to

approximately 10 minutes per visible pass. When KODAMA relays data

between a LEO spacecraft and a ground station, real-time communications

are possible in 60% of the flight path of the spacecraft. Japanese

ground controllers use telepresence robotics

to remotely conduct onboard research and experiments, thus reducing the

workload of station astronauts. Ground controllers also use a

free-floating autonomous ball camera to photodocument astronaut and space station activities, further freeing up astronaut time.

Cupola

The Cupola's design has been compared to the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars.

Dmitri Kondratyev and Paolo Nespoli in the Cupola. Background left to right, Progress M-09M, Soyuz TMA-20, the Leonardo module and HTV-2.

Cupola is a seven-window observatory, used to view Earth and docking spacecraft. Its name derives from the Italian word cupola,

which means "dome". The Cupola project was started by NASA and Boeing,

but cancelled due to budget cuts. A barter agreement between NASA and

ESA led to ESA resuming development of Cupola in 1998. It was built by

Thales Alenia Space in Turin, Italy. The module comes equipped with

robotic workstations for operating the station's main robotic arm and

shutters to protect its windows from damage caused by micrometeorites.

It features 7 windows, with an 80-centimetre (31 in) round window, the

largest window on the station (and the largest flown in space to date).

The distinctive design has been compared to the 'turret' of the

fictitious Millennium Falcon from the motion picture Star Wars; the original prop lightsaber used by actor Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker in the 1977 film was flown to the station in 2007.

Rassvet

Rassvet (Russian: Рассве́т; lit. "dawn"), also known as the Mini-Research Module 1 (MRM-1) (Russian: Ма́лый иссле́довательский модуль, МИМ 1) and formerly known as the Docking Cargo Module (DCM), is similar in design to the Mir Docking Module launched on STS-74 in 1995. Rassvet is primarily used for cargo storage and for docking by visiting spacecraft. It was flown to the ISS aboard NASA's Space Shuttle Atlantis on the STS-132 mission and connected in May 2010, Rassvet is the only Russian-owned module launched by NASA, to repay for the launch of Zarya, which is Russian designed and built, but partially paid for by NASA. Rassvet was launched with the Russian Nauka laboratory's experiments airlock temporarily attached to it, and spare parts for the European Robotic Arm.

Leonardo

Leonardo installed

Leonardo Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM) is a storage module attached to the Tranquility node. The three NASA Space Shuttle MPLM cargo containers—Leonardo, Raffaello and Donatello—were built for NASA in Turin, Italy by Alcatel Alenia Space, now Thales Alenia Space.

The MPLMs were provided to NASA's ISS programme by Italy (independent

of their role as a member state of ESA) and are considered to be US

elements. In a bartered exchange for providing these containers, the US

gave Italy research time aboard the ISS out of the US allotment in

addition to that which Italy receives as a member of ESA. The Permanent Multipurpose Module was created by converting Leonardo into a module that could be permanently attached to the station.

Bigelow Expandable Activity Module

Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) is a prototype inflatable space habitat serving as a two-year technology demonstration. It was built by Bigelow Aerospace under a contract established by NASA on 16 January 2013. BEAM was delivered to the ISS aboard SpaceX CRS-8 on 10 April 2016, was berthed to the aft port of the Tranquility node on 16 April, and was fully expanded on 28 May.

During its two-year test run, instruments are measuring its

structural integrity and leak rate, along with temperature and radiation

levels. The hatch leading into the module remains closed except for

periodic visits by space station crew members for inspections and data

collection. The module was originally planned to be jettisoned from the

station following the test, but following positive data after a year in orbit, NASA has suggested that it could remain on the station as a storage area.

International Docking Adapter-2

The International Docking Adapter (IDA) is a spacecraft docking system adapter being developed to convert APAS-95 to the NASA Docking System (NDS) / International Docking System Standard (IDSS). IDA-2 was launched on SpaceX CRS-9 on 18 July 2016. It was attached and connected to PMA-2 during a spacewalk on 19 August 2016.

Elements pending Russia launch

Nauka

Nauka (Russian: Нау́ка; lit. "science"), also known as the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM) or FGB-2 (Russian: Многофункциональный лабораторный модуль, МЛМ),

is the major Russian laboratory module. It was scheduled to arrive at

the station in 2014, docking to the port that was occupied by the Pirs module. Due to deterioration during many years spent in storage, it proved necessary to build a new propulsion module, and the launch date was postponed to 2018. Before the Nauka module arrives, a Progress spacecraft will remove Pirs from the station and deorbit it to reenter over the Pacific Ocean. Nauka

contains an additional set of life support systems and attitude

control. Originally it would have routed power from the single

Science-and-Power Platform, but that single module design changed over

the first ten years of the ISS mission, and the two science modules,

which attach to Nauka via the Uzlovoy Module, or Russian node, each incorporate their own large solar arrays to power Russian science experiments in the ROS.

Nauka's

mission has changed over time. During the mid-1990s, it was intended as

a backup for the FGB, and later as a universal docking module (UDM);

its docking ports will be able to support automatic docking of both

spacecraft, additional modules and fuel transfer. Nauka has its own engines. Like Zvezda and Zarya, Nauka will be launched by a Proton rocket, while smaller Russian modules such as Pirs and Poisk were delivered by modified Progress spacecraft. Russia plans to separate Nauka, along with the rest of the Russian Orbital Segment, to form the OPSEK space station before the ISS is deorbited.

Prichal

Prichal, also known as the Uzlovoy Module (UM), or Node Module is a 4-metric-ton

ball-shaped module that will allow docking of two scientific and power

modules during the final stage of the station assembly, and provide the

Russian segment additional docking ports to receive Soyuz MS and

Progress MS spacecraft. UM is due to be launched in 2020.

It will be integrated with a special version of the Progress cargo ship

and launched by a standard Soyuz rocket. Progress would use its own

propulsion and flight control system to deliver and dock the Node Module

to the nadir (Earth-facing) docking port of the Nauka MLM/FGB-2

module. One port is equipped with an active hybrid docking port, which

enables docking with the MLM module. The remaining five ports are

passive hybrids, enabling docking of Soyuz and Progress vehicles, as

well as heavier modules and future spacecraft with modified docking

systems. The node module was conceived to serve as the only permanent

element of the future Russian successor to the ISS, OPSEK.

Equipped with six docking ports, the Node Module would serve as a

single permanent core of the future station with all other modules

coming and going as their life span and mission required. This would be a progression beyond the ISS and Russia's modular Mir space station, which are in turn more advanced than early monolithic first generation stations such as Skylab, and early Salyut and Almaz stations.

Science Power Modules 1 and 2

(NEM-1, NEM-2) (Russian: Нау́чно-Энергетический Модуль-1 и -2)

Elements pending US launch

International Docking Adapter-3

The International Docking Adapter (IDA) is a spacecraft docking system adapter being developed to convert APAS-95 to the NASA Docking System (NDS)/ International Docking System Standard (IDSS). IDA-3 is scheduled to be launched on the SpaceX CRS-18 mission in May 2019. IDA-3 is being built mostly from spare parts to speed construction.

Bishop Airlock Module

The Bishop Airlock Module is a commercially-funded airlock module intended to be launched in 2019. The module is being built by NanoRacks and Boeing, and will be used to deploy CubeSats, small satellites, and other external payloads for NASA, CASIS, and other commercial and governmental customers. It is intended to be manifested with a Commercial Resupply Services mission.

The cancelled Habitation module under construction in 1997

Cancelled components

Several modules planned for the station were cancelled over the

course of the ISS programme. Reasons include budgetary constraints, the

modules becoming unnecessary, and station redesigns after the 2003 Columbia disaster. The US Centrifuge Accommodations Module would have hosted science experiments in varying levels of artificial gravity. The US Habitation Module would have served as the station's living quarters. Instead, the sleep stations are now spread throughout the station. The US Interim Control Module and ISS Propulsion Module would have replaced the functions of Zvezda in case of a launch failure. Two Russian Research Modules were planned for scientific research. They would have docked to a Russian Universal Docking Module. The Russian Science Power Platform would have supplied power to the Russian Orbital Segment independent of the ITS solar arrays.

Unpressurised elements

ISS Truss Components breakdown showing Trusses and all ORUs in situ

The ISS has a large number of external components that do not require pressurisation. The largest of these is the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS), to which the station's main solar arrays and thermal radiators are mounted. The ITS consists of ten separate segments forming a structure 108.5 m (356 ft) long.

The station in its complete form has several smaller external components, such as the six robotic arms, the three External Stowage Platforms (ESPs) and four ExPRESS Logistics Carriers (ELCs).[146][147] While these platforms allow experiments (including MISSE, the STP-H3 and the Robotic Refueling Mission)

to be deployed and conducted in the vacuum of space by providing

electricity and processing experimental data locally, their primary

function is to store spare Orbital Replacement Units

(ORUs). ORUs are parts that can be replaced when they fail or pass

their design life. Examples of ORUs include pumps, storage tanks,

antennas and battery units. Such units are replaced either by astronauts

during EVA or by robotic arms. Spare parts were routinely transported

to and from the station via Space Shuttle resupply missions, with a

heavy emphasis on ORU transport once the NASA Shuttle approached

retirement. Several shuttle missions were dedicated to the delivery of ORUs, including STS-129, STS-133 and STS-134. As of January 2011, only one other mode of transportation of ORUs had been utilised – the Japanese cargo vessel HTV-2 – which delivered an FHRC and CTC-2 via its Exposed Pallet (EP).

Construction of the Integrated Truss Structure over New Zealand.

There are also smaller exposure facilities mounted directly to laboratory modules; the Kibō Exposed Facility serves as an external 'porch' for the Kibō complex, and a facility on the European Columbus laboratory provides power and data connections for experiments such as the European Technology Exposure Facility and the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space. A remote sensing instrument, SAGE III-ISS, was delivered to the station in February 2017 aboard CRS-10, and the NICER experiment was delivered aboard CRS-11 in June 2017. The largest scientific payload externally mounted to the ISS is the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), a particle physics experiment launched on STS-134 in May 2011, and mounted externally on the ITS. The AMS measures cosmic rays to look for evidence of dark matter and antimatter.

The commercial Bartolomeo External Payload Hosting

Platform, manufactured by Airbus, is due to launch in May 2019 aboard a

commercial ISS resupply vehicle and be attached to the European Columbus module. It will provide a further 12 external payload slots, supplementing the eight on the ExPRESS Logistics Carriers, ten on Kibō, and four on Columbus.

The system is designed to be robotically serviced and will require no

astronaut intervention. It is named after Christopher Columbus's younger

brother.

Robotic arms and cargo cranes

Dextre, like many of the station's experiments and robotic arms, can be operated from Earth and perform tasks while the crew sleeps.

The Integrated Truss Structure serves as a base for the station's primary remote manipulator system, called the Mobile Servicing System (MSS), which is composed of three main components. Canadarm2,

the largest robotic arm on the ISS, has a mass of 1,800 kilograms

(4,000 lb) and is used to dock and manipulate spacecraft and modules on

the USOS, hold crew members and equipment in place during EVAs and move

Dextre around to perform tasks. Dextre

is a 1,560 kg (3,440 lb) robotic manipulator with two arms, a rotating

torso and has power tools, lights and video for replacing orbital replacement units (ORUs) and performing other tasks requiring fine control. The Mobile Base System

(MBS) is a platform which rides on rails along the length of the

station's main truss. It serves as a mobile base for Canadarm2 and

Dextre, allowing the robotic arms to reach all parts of the USOS. To gain access to the Russian Segment a grapple fixture was added to Zarya on STS-134, so that Canadarm2 can inchworm itself onto the ROS. Also installed during STS-134 was the 15 m (50 ft) Orbiter Boom Sensor System

(OBSS), which had been used to inspect heat shield tiles on Space

Shuttle missions and can be used on station to increase the reach of the

MSS.

Staff on Earth or the station can operate the MSS components via remote

control, performing work outside the station without space walks.

Japan's Remote Manipulator System, which services the Kibō Exposed Facility, was launched on STS-124 and is attached to the Kibō Pressurised Module.

The arm is similar to the Space Shuttle arm as it is permanently

attached at one end and has a latching end effector for standard grapple

fixtures at the other.

The European Robotic Arm, which will service the Russian Orbital Segment, will be launched alongside the Multipurpose Laboratory Module in 2017.

The ROS does not require spacecraft or modules to be manipulated, as

all spacecraft and modules dock automatically and may be discarded the

same way. Crew use the two Strela (Russian: Стрела́;

lit. Arrow) cargo cranes during EVAs for moving crew and equipment

around the ROS. Each Strela crane has a mass of 45 kg (99 lb).

Systems

Life support

The critical systems are the atmosphere control system, the water

supply system, the food supply facilities, the sanitation and hygiene

equipment, and fire detection and suppression equipment. The Russian

Orbital Segment's life support systems are contained in the Zvezda service module. Some of these systems are supplemented by equipment in the USOS. The MLM Nauka laboratory has a complete set of life support systems.

Atmospheric control systems

The interactions between the components of the ISS Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS)

The atmosphere on board the ISS is similar to the Earth's. Normal air pressure on the ISS is 101.3 kPa (14.7 psi);

the same as at sea level on Earth. An Earth-like atmosphere offers

benefits for crew comfort, and is much safer than a pure oxygen

atmosphere, because of the increased risk of a fire such as that

responsible for the deaths of the Apollo 1 crew. Earth-like atmospheric conditions have been maintained on all Russian and Soviet spacecraft.

The Elektron system aboard Zvezda and a similar system in Destiny generate oxygen aboard the station. The crew has a backup option in the form of bottled oxygen and Solid Fuel Oxygen Generation (SFOG) canisters, a chemical oxygen generator system. Carbon dioxide is removed from the air by the Vozdukh system in Zvezda. Other by-products of human metabolism, such as methane from the intestines and ammonia from sweat, are removed by activated charcoal filters.

Part of the ROS atmosphere control system is the oxygen supply.

Triple-redundancy is provided by the Elektron unit, solid fuel

generators, and stored oxygen. The primary supply of oxygen is the

Elektron unit which produces O

2 and H

2 by electrolysis of water and vents H2 overboard. The 1 kW system uses approximately one litre of water per crew member per day. This water is either brought from Earth or recycled from other systems. Mir was the first spacecraft to use recycled water for oxygen production. The secondary oxygen supply is provided by burning O

2-producing Vika cartridges (see also ISS ECLSS). Each 'candle' takes 5–20 minutes to decompose at 450–500 °C, producing 600 litres of O

2. This unit is manually operated.

2 and H

2 by electrolysis of water and vents H2 overboard. The 1 kW system uses approximately one litre of water per crew member per day. This water is either brought from Earth or recycled from other systems. Mir was the first spacecraft to use recycled water for oxygen production. The secondary oxygen supply is provided by burning O

2-producing Vika cartridges (see also ISS ECLSS). Each 'candle' takes 5–20 minutes to decompose at 450–500 °C, producing 600 litres of O

2. This unit is manually operated.

The US Orbital Segment has redundant supplies of oxygen, from a pressurised storage tank on the Quest airlock module delivered in 2001, supplemented ten years later by ESA-built Advanced Closed-Loop System (ACLS) in the Tranquility module (Node 3), which produces O

2 by electrolysis. Hydrogen produced is combined with carbon dioxide from the cabin atmosphere and converted to water and methane.

2 by electrolysis. Hydrogen produced is combined with carbon dioxide from the cabin atmosphere and converted to water and methane.

Power and thermal control

Russian solar arrays, backlit by sunset

One of the eight truss mounted pairs of USOS solar arrays

Double-sided solar, or Photovoltaic, arrays provide electrical power

for the ISS. These bifacial cells are more efficient and operate at a

lower temperature than single-sided cells commonly used on Earth, by

collecting sunlight on one side and light reflected off the Earth on the other.

The Russian segment of the station, like the Space Shuttle and most spacecraft, uses 28 volt DC from four rotating solar arrays mounted on Zarya and Zvezda.

The USOS uses 130–180 V DC from the USOS PV array, power is stabilised

and distributed at 160 V DC and converted to the user-required 124 V DC.

The higher distribution voltage allows smaller, lighter conductors, at the expense of crew safety. The ROS uses low voltage; the two station segments share power with converters.

The USOS solar arrays are arranged as four wing pairs, for a total production of 75 to 90 kilowatts. These arrays normally track the sun to maximise power generation. Each array is about 375 m2 (4,036 sq ft) in area and 58 m (190 ft) long. In the complete configuration, the solar arrays track the sun by rotating the alpha gimbal once per orbit; the beta gimbal follows slower changes in the angle of the sun to the orbital plane. The Night Glider mode

aligns the solar arrays parallel to the ground at night to reduce the

significant aerodynamic drag at the station's relatively low orbital

altitude.

The station uses rechargeable nickel–hydrogen batteries (NiH

2) for continuous power during the 35 minutes of every 90-minute orbit that it is eclipsed by the Earth. The batteries are recharged on the day side of the Earth. They have a 6.5-year lifetime (over 37,000 charge/discharge cycles) and will be regularly replaced over the anticipated 20-year life of the station. As of 2017, the nickel–hydrogen batteries are being replaced by lithium-ion batteries, which are expected to last until the end of the ISS program.

2) for continuous power during the 35 minutes of every 90-minute orbit that it is eclipsed by the Earth. The batteries are recharged on the day side of the Earth. They have a 6.5-year lifetime (over 37,000 charge/discharge cycles) and will be regularly replaced over the anticipated 20-year life of the station. As of 2017, the nickel–hydrogen batteries are being replaced by lithium-ion batteries, which are expected to last until the end of the ISS program.

The station's large solar panels generate a high potential

voltage difference between the station and the ionosphere. This could

cause arcing through insulating surfaces and sputtering of conductive

surfaces as ions are accelerated by the spacecraft plasma sheath. To

mitigate this, plasma contactor units (PCU)s create current paths

between the station and the ambient plasma field.

ISS External Active Thermal Control System (EATCS) diagram

The station's systems and experiments consume a large amount of

electrical power, almost all of which converts to heat. Little of this

heat dissipates through the walls of the station. To keep the internal

ambient temperature within comfortable, workable limits, ammonia

is continuously pumped through pipes throughout the station to collect

heat, then into external radiators to emit infrared radiation, then back

into the station. Thus this passive thermal control system (PTCS) is made of external surface materials, insulation such as MLI, and heat pipes.

If the PTCS cannot keep up with the heat load, an External Active

Thermal Control System (EATCS) maintains the temperature. The EATCS

consists of an internal, non-toxic, water coolant loop used to cool and

dehumidify the atmosphere, which transfers collected heat into an

external liquid ammonia loop that can withstand the much lower

temperature of space, and is circulated through radiators to remove the

heat. The EATCS provides cooling for all the US pressurised modules,

including Kibō and Columbus, as well as the main power

distribution electronics of the S0, S1 and P1 trusses. It can reject up

to 70 kW. This is much more than the 14 kW of the Early External Active

Thermal Control System (EEATCS) via the Early Ammonia Servicer (EAS),

which was launched on STS-105 and installed onto the P6 Truss.

Communications and computers

The communications systems used by the ISS

Radio communications provide telemetry and scientific data links between the station and Mission Control Centres. Radio links are also used during rendezvous and docking procedures and for audio and video communication between crew members, flight controllers and family members. As a result, the ISS is equipped with internal and external communication systems used for different purposes.

Radio communications provide telemetry and scientific data links between the station and Mission Control Centres. Radio links are also used during rendezvous and docking procedures and for audio and video communication between crew members, flight controllers and family members. As a result, the ISS is equipped with internal and external communication systems used for different purposes.

The Russian Orbital Segment communicates directly with the ground via the Lira antenna mounted to Zvezda. The Lira antenna also has the capability to use the Luch data relay satellite system. This system, used for communications with Mir, fell into disrepair during the 1990s, and so is no longer in use, although two new Luch satellites—Luch-5A and Luch-5B—were launched in 2011 and 2012 respectively to restore the operational capability of the system. Another Russian communications system is the Voskhod-M, which enables internal telephone communications between Zvezda, Zarya, Pirs, Poisk and the USOS, and also provides a VHF radio link to ground control centres via antennas on Zvezda's exterior.

The US Orbital Segment (USOS) makes use of two separate radio links mounted in the Z1 truss structure: the S band (used for audio) and Ku band (used for audio, video and data) systems. These transmissions are routed via the United States Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) in geostationary orbit, which allows for almost continuous real-time communications with NASA's Mission Control Center (MCC-H) in Houston. Data channels for the Canadarm2, European Columbus laboratory and Japanese Kibō modules are routed via the S band and Ku band systems, although the European Data Relay System and a similar Japanese system will eventually complement the TDRSS in this role. Communications between modules are carried on an internal digital wireless network.

An array of laptops in the US lab

Laptop computers surround the Canadarm2 console

UHF radio is used by astronauts and cosmonauts conducting EVAs.

UHF is used by other spacecraft that dock to or undock from the

station, such as Soyuz, Progress, HTV, ATV and the Space Shuttle (except

the shuttle also makes use of the S band and Ku band systems via TDRSS), to receive commands from Mission Control and ISS crewmembers. Automated spacecraft are fitted with their own communications equipment; the ATV uses a laser attached to the spacecraft and equipment attached to Zvezda, known as the Proximity Communications Equipment, to accurately dock to the station.

The ISS is equipped with about 100 IBM/Lenovo ThinkPad and HP ZBook 15 laptop computers. The laptops have run Windows 95, Windows 2000, Windows XP, Windows 7, Windows 10 and Linux operating systems. Each computer is a commercial off-the-shelf

purchase which is then modified for safety and operation including

updates to connectors, cooling and power to accommodate the station's

28V DC power system and weightless environment. Heat generated by the

laptops does not rise but stagnates around the laptop, so additional

forced ventilation is required. Laptops aboard the ISS are connected to

the station's wireless LAN via Wi-Fi and to the ground via Ku band. This provides speeds of 10 Mbit/s download and 3 Mbit/s upload from the station, comparable to home DSL connection speeds. Laptop hard drives have been known to fail occasionally, requiring manual replacement.

Other computer failures include instances in 2001, 2007 and 2017; some

of these failures have required EVAs to replace computers in externally

mounted devices.

The operating system used for key station functions is the Debian Linux distribution. The migration from Microsoft Windows was made in May 2013 for reasons of reliability, stability and flexibility.

Operations

Expeditions and private flight

Zarya and Unity were entered for the first time on 10 December 1998.

Soyuz TM-31 being prepared to bring the first resident crew to the station in October 2000

ISS was slowly assembled over a decade of spaceflights and crews

Each permanent crew is given an expedition number. Expeditions run up

to six months, from launch until undocking, an 'increment' covers the

same time period, but includes cargo ships and all activities.

Expeditions 1 to 6 consisted of 3 person crews, Expeditions 7 to 12 were

reduced to the safe minimum of two following the destruction of the

NASA Shuttle Columbia. From Expedition 13 the crew gradually increased

to 6 around 2010. With the arrival of the American Commercial Crew vehicles in the middle of the 2010s, expedition size may be increased to seven crew members, the number ISS is designed for.

Gennady Padalka, member of Expeditions 9, 19/20, 31/32, and 43/44, and Commander of Expedition 11, has spent more time in space than anyone else, a total of 878 days, 11 hours, and 29 minutes. Peggy Whitson has spent the most time in space of any American, totalling 665 days, 22 hours, and 22 minutes during her time on Expeditions 5, 16, and 50/51/52.

Travellers who pay for their own passage into space are termed spaceflight participants by Roscosmos and NASA, and are sometimes referred to as space tourists, a term they generally dislike.[note 1]

All seven were transported to the ISS on Russian Soyuz spacecraft. When

professional crews change over in numbers not divisible by the three

seats in a Soyuz, and a short-stay crewmember is not sent, the spare

seat is sold by MirCorp through Space Adventures. When the space shuttle

retired in 2011, and the station's crew size was reduced to 6, space

tourism was halted, as the partners relied on Russian transport seats

for access to the station. Soyuz flight schedules increase after 2013,

allowing 5 Soyuz flights (15 seats) with only two expeditions (12 seats)

required. The remaining seats are sold for around US$40 million

to members of the public who can pass a medical exam. ESA and NASA

criticised private spaceflight at the beginning of the ISS, and NASA

initially resisted training Dennis Tito, the first man to pay for his own passage to the ISS.

Anousheh Ansari

became the first Iranian in space and the first self-funded woman to

fly to the station. Officials reported that her education and experience

make her much more than a tourist, and her performance in training had

been "excellent."

Ansari herself dismisses the idea that she is a tourist. She did

Russian and European studies involving medicine and microbiology during

her 10-day stay. The documentary Space Tourists

follows her journey to the station, where she fulfilled "an age-old

dream of man: to leave our planet as a "normal person" and travel into

outer space."

In 2008, spaceflight participant Richard Garriott placed a geocache aboard the ISS during his flight. This is currently the only non-terrestrial geocache in existence. At the same time, the Immortality Drive, an electronic record of eight digitised human DNA sequences, was placed aboard the ISS.

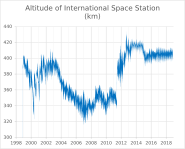

Orbit

Graph showing the changing altitude of the ISS from November 1998 until November 2018

Animation of ISS orbit from 14 September 2018 to 14 November 2018. Earth is not shown.

The ISS is maintained in a nearly circular orbit with a minimum mean

altitude of 330 km (205 mi) and a maximum of 410 km (255 mi), in the

centre of the thermosphere, at an inclination of 51.6 degrees to Earth's equator, necessary to ensure that Russian Soyuz and Progress spacecraft launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome

may be safely launched to reach the station. Spent rocket stages must

be dropped into uninhabited areas and this limits the directions rockets

can be launched from the spaceport.

It travels at an average speed of 27,724 kilometres per hour

(17,227 mph), and completes 15.54 orbits per day (93 minutes per orbit).

The station's altitude was allowed to fall around the time of each NASA

shuttle mission. Orbital boost burns would generally be delayed until

after the shuttle's departure. This allowed shuttle payloads to be

lifted with the station's engines during the routine firings, rather

than have the shuttle lift itself and the payload together to a higher

orbit. This trade-off allowed heavier loads to be transferred to the

station. After the retirement of the NASA shuttle, the nominal orbit of

the space station was raised in altitude. Other, more frequent supply ships do not require this adjustment as they are substantially lighter vehicles.

Orbital boosting can be performed by the station's two main engines on the Zvezda service module, or Russian or European spacecraft docked to Zvezda's aft port. The ATV has been designed with the possibility of adding a second docking port

to its other end, allowing it to remain at the ISS and still allow

other craft to dock and boost the station. It takes approximately two

orbits (three hours) for the boost to a higher altitude to be completed. Maintaining ISS altitude uses about 7.5 tonnes of chemical fuel per annum at an annual cost of about $210 million.

Orbits of the ISS, shown in April 2013

In December 2008 NASA signed an agreement with the Ad Astra Rocket Company which may result in the testing on the ISS of a VASIMR plasma propulsion engine. This technology could allow station-keeping to be done more economically than at present.

The Russian Orbital Segment contains the Data Management System,

which handles Guidance, Navigation and Control (ROS GNC) for the entire

station. Initially, Zarya, the first module of the station, controlled the station until a short time after the Russian service module Zvezda docked and was transferred control. Zvezda contains the ESA built DMS-R Data Management System. Using two fault-tolerant computers (FTC), Zvezda

computes the station's position and orbital trajectory using redundant

Earth horizon sensors, Solar horizon sensors as well as Sun and star

trackers. The FTCs each contain three identical processing units working

in parallel and provide advanced fault-masking by majority voting.

Orientation

Zvezda uses gyroscopes (reaction wheels)

and thrusters to turn itself around. Gyroscopes do not require

propellant, rather they use electricity to 'store' momentum in flywheels

by turning in the opposite direction to the station's movement. The

USOS has its own computer controlled gyroscopes to handle the extra mass

of that section. When gyroscopes 'saturate', thrusters are used to cancel out the stored momentum. During Expedition 10,

an incorrect command was sent to the station's computer, using about 14

kilograms of propellant before the fault was noticed and fixed. When

attitude control computers in the ROS and USOS fail to communicate

properly, it can result in a rare 'force fight' where the ROS GNC

computer must ignore the USOS counterpart, which has no thrusters.

When an ATV, NASA Shuttle, or Soyuz is docked to the station, it can

also be used to maintain station attitude such as for troubleshooting.

Shuttle control was used exclusively during installation of the S3/S4 truss, which provides electrical power and data interfaces for the station's electronics.

Mission controls

The components of the ISS are operated and monitored by their respective space agencies at mission control centres across the globe, including:

- Roscosmos's Mission Control Center at Korolyov, Moscow Oblast, controls the Russian Orbital Segment which handles Guidance, Navigation and Control for the entire Station, in addition to individual Soyuz and Progress missions.

- ESA's ATV Control Centre, at the Toulouse Space Centre (CST) in Toulouse, France, controls flights of the unmanned European Automated Transfer Vehicle.

- JAXA's JEM Control Center and HTV Control Center at Tsukuba Space Center (TKSC) in Tsukuba, Japan, are responsible for operating the Kibō complex and all flights of the 'White Stork' HTV Cargo spacecraft, respectively.

- NASA's Mission Control Center at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, serves as the primary control facility for the United States segment of the ISS and also controlled the Space Shuttle missions that visited the station.

- NASA's Payload Operations and Integration Center at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, coordinates payload operations in the USOS.

- ESA's Columbus Control Centre at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany, manages the European Columbus research laboratory.

- CSA's MSS Control at Saint-Hubert, Quebec, Canada, controls and monitors the Mobile Servicing System, or Canadarm2.

Repairs

While anchored on the end of the OBSS during STS-120, astronaut Scott Parazynski performs makeshift repairs to a US solar array which damaged itself when unfolding.

Mike Hopkins on his Christmas Eve spacewalk

Orbital Replacement Units

(ORUs) are spare parts that can be readily replaced when a unit either

passes its design life or fails. Examples of ORUs are pumps, storage

tanks, controller boxes, antennas, and battery units. Some units can be

replaced using robotic arms. Many are stored outside the station, either

on small pallets called ExPRESS Logistics Carriers (ELCs) or share larger platforms called External Stowage Platforms

which also hold science experiments. Both kinds of pallets have

electricity as many parts which could be damaged by the cold of space

require heating. The larger logistics carriers also have computer local

area network connections (LAN) and telemetry to connect experiments. A

heavy emphasis on stocking the USOS with ORU's occurred around 2011,

before the end of the NASA shuttle programme, as its commercial

replacements, Cygnus and Dragon, carry one tenth to one quarter the payload.

Unexpected problems and failures have impacted the station's

assembly time-line and work schedules leading to periods of reduced

capabilities and, in some cases, could have forced abandonment of the

station for safety reasons, had these problems not been resolved. During

STS-120

in 2007, following the relocation of the P6 truss and solar arrays, it

was noted during the redeployment of the array that it had become torn

and was not deploying properly. An EVA was carried out by Scott Parazynski, assisted by Douglas Wheelock.

The men took extra precautions to reduce the risk of electric shock, as

the repairs were carried out with the solar array exposed to sunlight.

The issues with the array were followed in the same year by problems

with the starboard Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ), which rotates the

arrays on the starboard side of the station. Excessive vibration and

high-current spikes in the array drive motor were noted, resulting in a

decision to substantially curtail motion of the starboard SARJ until the

cause was understood. Inspections during EVAs on STS-120 and STS-123

showed extensive contamination from metallic shavings and debris in the

large drive gear and confirmed damage to the large metallic race ring

at the heart of the joint, and so the joint was locked to prevent

further damage. Repairs to the joint were carried out during STS-126 with lubrication of both joints and the replacement of 11 out of 12 trundle bearings on the joint.

2009 saw damage to the S1 radiator, one of the components of the station's cooling system. The problem was first noticed in Soyuz imagery in September 2008, but was not thought to be serious.

The imagery showed that the surface of one sub-panel has peeled back

from the underlying central structure, possibly because of

micro-meteoroid or debris impact. It is also known that a Service Module

thruster cover, jettisoned during an EVA in 2008, had struck the S1