| |

| Geographical range | Afro-Eurasia |

|---|---|

| Period | Lower Paleolithic |

| Dates | 2.6 million years BP – 1.7 million years BP |

| Major sites | Olduvai Gorge |

| Preceded by | Lomekwian |

| Followed by | Acheulean, Riwat |

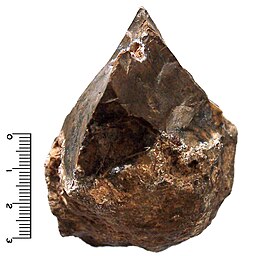

The Oldowan (or Mode I) is the earliest widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory.

These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes

chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower Paleolithic period, 2.6 million years ago up until 1.7 million years ago, by ancient Hominin (early humans) across much of Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and Europe. This technological industry was followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry.

Oldowan is pre-dated by Lomekwian tools at a single site dated to 3.3 mya (million years ago). It is not clear if the Lomekwian industry bears any relation to the Oldowan.

The term Oldowan is taken from the site of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where the first Oldowan lithics were discovered by the archaeologist Louis Leakey in the 1930s. However, some contemporary archaeologists and palaeoanthropologists prefer to use the term Mode 1 tools to designate pebble tool industries (including Oldowan), with Mode 2 designating bifacially worked tools (including Acheulean handaxes), Mode 3 designating prepared-core tools, and so forth.

Classification of Oldowan tools is still somewhat contentious. Mary Leakey

was the first to create a system to classify Oldowan assemblages, and

built her system based on prescribed use. The system included choppers, scrapers, and pounders.

However, more recent classifications of Oldowan assemblages have been

made that focus primarily on manufacture due to the problematic nature

of assuming use from stone artefacts. An example is Isaac et al.'s

tri-modal categories of "Flaked Pieces" (cores/choppers), "Detached

Pieces" (flakes and fragments), "Pounded Pieces" (cobbles utilized as

hammerstones, etc.) and "Unmodified Pieces" (manuports, stones

transported to sites).

Oldowan tools are sometimes called "pebble tools", so named because the

blanks chosen for their production already resemble, in pebble form,

the final product.

It is not known for sure which hominin species created and used

Oldowan tools. Its emergence is often associated with the species Australopithecus garhi and its flourishing with early species of Homo such as H. habilis and H. ergaster. Early Homo erectus appears to inherit Oldowan technology and refines it into the Acheulean industry beginning 1.7 million years ago.

Dates and ranges

The oldest known Oldowan tools have been found in Gona, Ethiopia, and are dated to about 2.6 mya.

The use of tools by apes including chimpanzees and orangutans can be used to argue in favour of tool-use as an ancestral feature of the hominin family. Tools made from bone, wood, or other organic materials were therefore in all probability used before the Oldowan. Oldowan stone tools are simply the oldest recognisable tools which have been preserved in the archaeological record.

There is a flourishing of Oldowan tools in eastern Africa,

spreading to southern Africa, between 2.4 and 1.7 mya. At 1.7 mya., the

first Acheulean tools appear even as Oldowan assemblages continue to be

produced. Both technologies are occasionally found in the same areas,

dating to the same time periods. This realisation required a rethinking

of old cultural sequences in which the more "advanced" Acheulean was

supposed to have succeeded the Oldowan. The different traditions may

have been used by different species of hominins living in the same area,

or multiple techniques may have been used by an individual species in

response to different circumstances.

Sometime before 1.8 mya Homo erectus had spread outside of Africa, reaching as far east as Java by 1.8 mya and in Northern China by 1.66 mya.

In these newly colonised areas, no Acheulean assemblages have been

found. In China, only "Mode 1" Oldowan assemblages were produced, while

in Indonesia stone tools from this age are unknown.

By 1.8 mya early Homo was present in Europe, as shown by the discovery of fossil remains and Oldowan tools in Dmanisi, Georgia. Remains of their activities have also been excavated in Spain at sites in the Guadix-Baza basin and near Atapuerca.

Most early European sites yield "Mode 1" or Oldowan assemblages. The

earliest Acheulean sites in Europe only appear around 0.5 mya. In

addition, the Acheulean tradition does not seem to spread to Eastern

Asia.

It is unclear from the archaeological record when the production of

Oldowan technologies ended. Other tool-making traditions seem to have

supplanted Oldowan technologies by 0.25 mya.

Tools

Manufacture

To obtain an Oldowan tool, a roughly spherical hammerstone is struck on the edge, or striking platform, of a suitable core rock to produce a conchoidal fracture with sharp edges useful for various purposes. The process is often called lithic reduction. The chip removed by the blow is the flake.

Below the point of impact on the core is a characteristic bulb with

fine fissures on the fracture surface. The flake evidences ripple marks.

The materials of the tools were for the most part quartz, quartzite, basalt, or obsidian, and later flint and chert.

Any rock that can hold an edge will do. The main source of these rocks

is river cobbles, which provide both hammer stones and striking

platforms. The earliest tools were simply split cobbles. It is not

always clear which is the flake. Later tool-makers clearly identified

and reworked flakes. Complaints that artifacts could not be

distinguished from naturally fractured stone have helped spark careful

studies of Oldowon techniques. These techniques have now been duplicated

many times by archaeologists and other knappers, making

misidentification of archaeological finds less likely.

Use of bone tools by hominins also producing Oldowan tools is known from Swartkrans, where a bone shaft with a polished point was discovered in Member (layer) I, dated 1.8–1.5 mya. The Osteodontokeratic industry, the "bone-tooth-horn" industry hypothesized by Raymond Dart, is less certain.

Shapes and uses

Oldowan-tradition stone chopper.

Mary Leakey classified the Oldowan tools as Heavy Duty, Light Duty, Utilized Pieces and Debitage, or waste. Heavy-duty tools are mainly cores. A chopper

has an edge on one side. It is unifacial if the edge was created by

flaking on one face of the core, or bifacial if on two. Discoid tools

are roughly circular with a peripheral edge. Polyhedral tools are edged

in the shape of a polyhedron. In addition there are spheroidal hammer

stones.

Light-duty tools are mainly flakes. There are scrapers, awls (with points for boring) and burins

(with points for engraving). Some of these functions belong also to

heavy-duty tools. For example, there are heavy-duty scrapers.

Utilized pieces are tools that began with one purpose in mind but were utilized opportunistically.

Oldowan tools were probably used for many purposes, which have

been discovered from observation of modern apes and hunter-gatherers.

Nuts and bones are cracked by hitting them with hammer stones on a stone

used as an anvil. Battered and pitted stones testify to this possible

use.

Heavy-duty tools could be used as axes for woodworking. Both

choppers and large flakes were probably used for this purpose. Once a

branch was separated, it could be scraped clean with a scraper, or

hollowed with pointed tools. Such uses are attested by characteristic

microscopic alterations of edges used to scrape wood. Oldowan tools

could also have been used for preparing hides. Hides must be cut by

slicing, piercing and scraping them clean of residues. Flakes are most

suitable for this purpose.

Lawrence Keeley, following in the footsteps of Sergei Semenov,

conducted microscopic studies (with a high-powered optical microscope)

on the edges of tools manufactured de novo and used for the

originally speculative purposes described above. He found that the marks

were characteristic of the use and matched marks on prehistoric tools.

Studies of the cut marks on bones using an electron microscope produce a

similar result.

Abbevillian

Abbevillian is a currently obsolescent name for a tool tradition that

is increasingly coming to be called Oldowan. The label Abbevillian

prevailed until the Leakey family discovered older (yet similar)

artifacts at Olduvai Gorge (a.k.a. Oldupai Gorge) and promoted the

African origin of man. Oldowan soon replaced Abbevillian in describing

African and Asian lithics. The term Abbevillian is still used but is now

restricted to Europe. The label, however, continues to lose popularity

as a scientific designation.

In the late 20th century, discovery of the discrepancies in date

caused a crisis of definition. If Abbevillian did not necessarily

precede Acheulean and both traditions had flakes and bifaces, how was

the difference to be defined? It was in this spirit that many artifacts

formerly considered Abbevillian were labeled Acheulean. In consideration

of the difficulty, some preferred to name both phases Acheulean. When

the topic of Abbevillian came up, it was simply put down as a phase of

Acheulean. Whatever was from Africa was Oldowan, and whatever from

Europe, Acheulean.

The solution to the definition problem is stated in the article

on Acheulean. The difference is to be defined in terms of complexity.

Simply struck tools are Oldowan. Retouched, or reworked tools are

Acheulean. Retouching is a second working of the artifact. The

manufacturer first creates an Oldowan tool. Then he reworks or retouches

the edges by removing very small chips so as to straighten and sharpen

the edge. Typically but not necessarily the reworking is accomplished by

pressure flaking.

The pictures in the introduction to this article are mainly

labeled Acheulean, but this is the now false Acheulean, which also

includes Abbevillian. The artifacts shown are clearly in the Oldowan

tradition. One or two of the more complex bifaces may have edges made

straighter by a large percussion or two, but there is no sign of

pressure flaking as depicted. The pictures included with this subsection

show the difference.

Tool users

Current anthropological thinking is that Oldowan tools were made by late Australopithecus and early Homo. Homo habilis was named "skillful" because it was considered the earliest tool-using human ancestor.

Indeed, the genus Homo was in origin intended to separate tool-using species from their tool-less predecessors, hence the name of Australopithecus garhi, garhi meaning "surprise", a tool-using Australopithecine discovered in 1996 and described as the "missing link" between the Australopithecus and Homo genera. There is also evidence that some species of Paranthropus utilized stone tools.

Artistic interpretation of a female member of the Australopithecus genus. The emergence of Oldowan tools is often associated with the species Australopithecus garhi.

There is presently no evidence to show that Oldowan tools were the sole creation of members of the Homo

line or that the ability to produce them was a special characteristic

of only our ancestors. Research on tool use by modern wild chimpanzees

in West Africa shows there is an operational sequence when chimpanzees

use lithic implements to crack nuts. In the course of nut cracking,

sometimes they will create unintentional flakes. Although the morphology

of chimpanzees' hammer is different from Oldowan hammer, chimpanzees'

ability to use stone tools indicates that the earliest lithic industries

were probably not produced by only one kind of hominin species.

The makers of Oldowan tools were mainly right-handed. "Handedness" (lateralization)

had thus already evolved, though it is not clear how related to modern

lateralization it was, since other animals show handedness as well.

In the mid-1970s, Glynn Isaac

touched off a debate by proposing that human ancestors of this period

had a "place of origin" and that they foraged outward from this home

base, returning with high-quality food to share

and to be processed. Over the course of the last 30 years, a variety of

competing theories about how foraging occurred have been proposed, each

one implying certain kinds of social strategy. The available evidence

from the distribution of tools and remains is not enough to decide which

theories are the most probable. However, three main groups of theories

predominate.

- Glynn Isaac's model became the Central Forage Point, as he responded to critics that accused him of attributing too much "modern" behavior to early hominins with relatively free-form searches outward.

- A second group of models took modern chimpanzee behavior as a starting point, having the hominids use relatively fixed routes of foraging, and leaving tools where it was best to do so on a constant track.

- A third group of theories had relatively loose bands scouring the range, taking care to move carcasses from dangerous death sites and leaving tools more or less at random.

Each group of models implies different grouping and social

strategies, from the relative altruism of central base models to the

relatively disjointed search models.

Hominins probably lived in social groups that had contact with

others. This conclusion is supported by the large number of bones at

many sites, too large to be the work of one individual, and all of the

scatter patterns implying many different individuals. Since modern

primates in Africa have fluid boundaries between groups, as individuals

enter, become the focus of bands, and others leave, it is also probable

that the tools we find are the result of many overlapping groups working

the same territories, and perhaps competing over them. Because of the

huge expanse of time and the multiplicity of species associated with

possible Oldowan tools, it is difficult to be more precise than this,

since it is almost certain that different social groupings were used at

different times and in different places.

There is also the question of what mix of hunting, gathering and

scavenging the tool users employed. Early models focused on the tool

users as hunters. The animals butchered by the tools include waterbuck, hartebeest, springbok, pig and zebra.

However, the disposition of the bones allows some question about

hominin methods of obtaining meat. That they were omnivores is

unquestioned, as the digging implement and the probable use of hammer

stones to smash nuts indicate. Lewis Binford first noticed that the

bones at Olduvai contained a disproportionately high incidence of

extremities, which are low in food substance. He concluded other

predators had taken the best meat, and the hominins had only scavenged.

The counter view is that while hunting many large animals would be

beyond the reach of an individual human, groups could bring down larger

game, as pack hunting animals are capable of doing. Moreover, since many

animals both hunt and scavenge, it is possible that hominins hunted

smaller animals, but were not above driving carnivores from larger

kills, as they probably were driven from kills themselves from time to

time.

Sites and archaeologists

Africa

Ethiopia

Oldowan choppers dating to 1.7 million years BP, from Melka Kunture, Ethiopia

Afar Triangle

Sites in the Gona river system in the Hadar region of the Afar triangle,

excavated by Helene Roche, J. W. Harris and Sileshi Semaw, yielded some

of the oldest known Oldowan assemblages, dating to about 2.6 million

years ago. Raw material analysis done by Semaw showed that some

assemblages in this region are biased towards a certain material (e.g.:

70% of the artifacts at sites EG10 and EG12 were composed of trachyte)

indicating a selectivity in the quality of stone used.

Recent excavations have yielded tools in association with cut-marked

bones, indicating that Oldowan were used in meat-processing or

-acquiring activities.

Omo River basin

The second oldest known Oldowan tool site comes from the Shungura formation of the Omo River basin. This formation documents the sediments of the Plio-Pleistocene

and provides a record of the hominins that lived there. Lithic

assemblages have been classified as Oldowan in members E and F in the

lower Omo basin. Although there have been lithic assemblages found in

multiple sites in these areas, only the Omo sites 57 and 123 in member F

are accepted as hominin lithic remains. The assemblages at Omo sites 71

and 84 in member E do not show evidence of hominin modification and are

therefore classified as natural assemblages.

The tools are never found in direct association with the

hominins, but archaeologists believe that they would be the strongest

candidates for tool manufacture. There are no hominins in those layers,

but the same layers elsewhere in the Omo valley contain Paranthropus and early Homo fossils. Paranthropus occurs in the preceding layers. In the last layer at 1.4 million years ago is only Homo erectus.

Egypt

Along the Nile River, within the 100-foot terrace, evidence of Chellean or Oldowan cultures has been found.

Algeria

In

November 2018 Science published a report of Oldowan artefacts in a

secure dating context of 1.9 to 2.4 million years from four levels in

the foothills of the Atlas mountains near the Algerian coast.

Kenya

Kanjera South, part of the Kanjera site complex, is located on the Homa Peninsula. The site is estimated around 2 million years old. One of the significant excavations, in the area, is Leakey’s expedition in 1932-35. In 1995, Oldowan and Plio-Pleistocene faunal remains surfaced from the site. There has been fieldwork to understand the geochronology of Kanjera.

East Turkana

The numerous Koobi Fora sites on the east side of Lake Turkana are now part of Sibiloi National Park. Sites were initially excavated by Richard Leakey, Meave Leakey, Jack Harris, Glynn Isaac

and others. Currently the artifacts found are classified as Oldowan or

KBS Oldowan dated from 1.9–1.7 mya, Karari (or "advanced Oldowan") dated

to 1.6–1.4 mya, and some early Acheulean at the end of the Karari. Over

200 hominins have been found, including Australopithecus and Homo.

Tanzania

Olduvai Gorge

Chopper from Olduvai Gorge, some 1.8 million years old

The Oldowan industry is named after discoveries made in the Olduvai Gorge of Tanzania in east Africa by the Leakey family, primarily Mary Leakey, but also her husband Louis and their son, Richard.

Mary Leakey organized a typology of Early Pleistocene stone tools,

which developed Oldowan tools into three chronological variants, A, B

and C.

Developed Oldowan B is of particular interest due to changes in

morphology that appear to have been driven mostly by the short term

availability of a chert resource from 1.65 mya to 1.53 mya. The flaking

properties of this new resource resulted in considerably more core

reduction and a higher prevalence of flake retouch.

Similar tools had already been found in various locations in Europe and

Asia for some time, where they were called Chellean and Abbevillian.

The oldest tool sites are in the East African Rift system, on the sediments of ancient streams and lakes. This is consistent with what we surmise of the evolution of man. Genetic studies tell us that the human line (the hominins) possibly diverged from the chimpanzee line (the hominids), and the native territory of the latter is the forests of Central Africa nearby. Fossil chimpanzees have been found in Kenya.

The forests of central and western Africa are a stable

environment containing food in abundance for animals such as

chimpanzees, and any species living in such an environment would have

been under little pressure to evolve further. Eastern Africa is a land

of often harsh and unstable environments, and resources are

correspondingly scarcer and more difficult to get. Species living in the

latter environment would be under greater pressure to evolve and change

as needed to survive. A facility for tool-using would contribute to the

species' chances of survival.

Even though Olduvai Gorge is the type site, Oldowan tools from

here are not the oldest known examples. They occur in Beds I–IV. Bed I,

dated 1.85 mya to 1.7 mya, contains Oldowan and fossils of Paranthropus boisei as well as Homo habilis, as does Bed II, 1.7–1.2 mya. H. habilis gives way to Homo erectus at about 1.6 mya but P. boisei goes on. Oldowan continues to Bed IV at 800,000 to 600,000 before present (BP).

South Africa

Abbé Breuil

was the first recognized archaeologist to go on record to assert the

existence of Oldowan tools. While his description was for "Chello-Abbevillean" tools, and post-dated Leakey's finds at Olduvai Gorge

by at least ten years, his descriptions nonetheless represented the

scholarly acceptance of this technology as legitimate. These findings

were cited as being from the location of the Vaal River, at Vereeniging,

and Breuil noted the distinct absence of a significant number of cores,

suggesting a "portable culture". At the time, this was considered very

significant, as portability supported the conclusion that the Oldowan

tool-makers were capable of planning for future needs, by creating the

tools in a location which was distant from their use.

Swartkrans

The Swartkrans

site is a cave filled with layered fossil-bearing limestone deposits.

Oldowan is found in Members (layers) I–III, 1.8–.5 mya, in association

with Paranthropus robustus and Homo habilis. The Member I assemblage also includes a shaft of pointed bone polished at the pointed end.

Member I contained a high percentage of primate remains compared to other animal remains, which did not fit the hypothesis that H. habilis or P. robustus

lived in the cave. C. K. Brain conducted a more detailed study and

discovered the cave had been the abode of leopards, who preyed on the

hominins.

Sterkfontein

Another site of limestone caves is Sterkfontein, found in South Africa. This site contains a large number of not only Oldowan tools, but also early Acheulean technology.

Europe

Georgia

Stone tool (Oldowan style) from Dmanisi paleontological site (right, 1.8 mya, replica), to be compared with the more "modern" Acheulean style (left)

In 1999 and 2002, two Homo erectus skulls (H. georgicus) were discovered at Dmanisi

in southern Georgia. The archaeological layer in which the human

remains, hundreds of Oldowan stone tools, and numerous animal bones were

unearthed is dated approximately 1.6-1.8 million years ago. The site

yields the earliest unequivocal evidence for presence of early humans

outside the African continent.

Bulgaria

At Kozarnika,

in the ground layers, dated to 1.4-1.6 Ma, archaeologists have

discovered a human molar tooth, lower palaeolithic assemblages that

belong to a core-and-flake non-Acheulian industry and incised bones that

may be the earliest example of human symbolic behaviour.

Russia

Ainikab-1 and Muhkay-2 (North Caucasus, Daghestan)

are the extraordinary sites in relation to date and the culture.

Geological and geomorphological data, palynological studies and

paleomagnetic testing unequivocally point to Early Pleistocene (Eopleistocene), indicating the age of the sites as being within the range of 1.8 – 1.2 Ma.

Spain

Extremely archaic handaxe from the Quaternary fluvial terraces of Duero river (Valladolid, Spain) dated to Oldowan/Abbevillian period (Lower Paleolithic).

Typical Acheulean handaxe with tear form, from a superficial site in the Zamora province (Spain), in the Duero river.

Oldowan tools have been found at the following sites: Fuente Nueva 3, Barranco del Leon, Sima del Elefante, Atapuerca TD 6.

France

Oldowan tools have been found at: Lézignan-la-Cèbe, 1.5 mya; Abbeville, 1–.5 mya; Vallonnet cave, French Riviera; Soleihac, open-air site in Massif Central. Oldowan tools have also been found at Tautavel in the foothills of the Pyrenees. These were discovered by Henry de Lumbley alongside human remains (cranium). The tools are of limestone and quartz.

Elsewhere

Oldowan tools have been found in Italy at the Monte Poggiolo

open air site dated to approximately 850 kya, making them the oldest

evidence of human habitation in Italy. In Germany tools have been found

in river gravels at Kärlich

dating from 300 kya. In the Czech Republic tools have been found in

ancient lake deposits at Przeletice and a cave site at Stranska Skala,

dated no later than 500 kya. In Hungary tools have been found at a

spring site at Vértesszőlős dating from 500 kya.

Asia

Oldowan tools have been found at sites in South Asia and Southwest Asia. In November 2008 tens of sites of Oldowan tools industry were found on the island of Socotra (Yemen).