Types of fallout

Atmospheric nuclear weapon tests almost doubled the concentration of radioactive 14C in the Southern Hemisphere, before levels slowly declined following the Partial Test Ban Treaty.

Fallout comes in two varieties. The first is a small amount of

carcinogenic material with a long half-life. The second, depending on

the height of detonation, is a huge quantity of radioactive dust and

sand with a short half-life.

All nuclear explosions produce fission

products, un-fissioned nuclear material, and weapon residues vaporized

by the heat of the fireball. These materials are limited to the original

mass of the device, but include radioisotopes with long lives. When the nuclear fireball does not reach the ground, this is the only fallout produced. Its amount can be estimated from the fission-fusion design and weight of the weapon. A modern W89 warhead weighs 324 pounds (147 kg). The fission bomb dropped on Hiroshima (Little Boy) weighed 9,700 pounds (4,400 kg).

Global fallout

After the detonation of a weapon at or above the fallout-free altitude (an air burst), fission

products, un-fissioned nuclear material, and weapon residues vaporized

by the heat of the fireball condense into a suspension of particles 10 nm to 20 µm in diameter. This size of particulate matter, lifted to the stratosphere, may take months or years to settle, and may do so anywhere in the world.

Its radioactive characteristics increase the statistical cancer risk.

Elevated atmospheric radioactivity remains measurable after the

widespread nuclear testing of the 1950s.

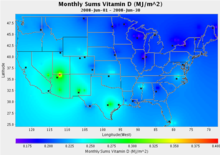

Radioactive fallout has occurred around the world, for example people have been exposed to "Iodine-131"

from atmospheric nuclear testing. Fallout accumulates on vegetation,

including fruits and vegetables. Starting from 1951 people may have

gotten exposure, depending on, whether they were outside, the weather

forecast, and whether they drank contaminated milk, vegetables or fruit.

Exposure can be on an intermediate time scale or long term.

The intermediate time scale results from fallout that has been put into

the troposphere and ejected by precipitation during the first month.

Long term fallout can sometimes occur from deposition of tiny particles

carried in the stratosphere.

By the time that stratospheric fallout has begun to reach the earth,

the radioactivity is very much decreased. Also, after a year it is

estimated that a sizable quantity of fission products move from the

northern to the southern stratosphere. The intermediate time scale is

between 1–30 days, with long term fallout occurring after that.

Examples of both intermediate and long term fallout occurred after the Chernobyl accident.

Chernobyl was a nuclear power facility in Soviet Russia, and in 1986 it

accidentally contaminated over about 5 million acres in Ukraine. The main fuel of the reactor was Uranium,

and surrounding this was graphite, both of which were vaporized by the

hydrogen explosion that destroyed the reactor and breached its

containment. An estimated 31 people died within a few weeks after this

happened, including two plant workers killed at the scene. Although

residents were evacuated within 36 hours, people started to complain of

vomiting, migraines and other major signs of radiation sickness. The officials of Ukraine had to close off an 18-mile area. Long term effects included at least 6000 cases of thyroid cancer,

mainly among children. Fallout spread throughout Western Europe, with

Northern Scandinavia receiving a heavy dose, contaminating reindeer

herds in Lapland, and salad greens becoming almost unavailable in

France.

Local fallout

During detonations of devices at ground level (surface burst), below the fallout-free altitude, or in shallow water, heat vaporizes large amounts of earth or water, which is drawn up into the radioactive cloud. This material becomes radioactive when it combines with fission products or other radiocontaminants, or when it is neutron-activated.

The table below summarizes the abilities of common isotopes to form fallout. Some radiation taints large amounts of land and drinking water causing formal mutations throughout animal and human life.

The 450 km (280 mi) fallout plume from 15 Mt shot Castle Bravo, 1954

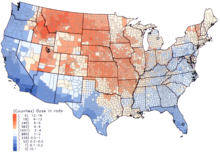

Per capita thyroid doses in the continental United States resulting from all exposure routes from all atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site from 1951–1962

A surface burst generates large amounts of particulate matter, composed of particles from less than 100 nm to several millimeters in diameter—in addition to very fine particles that contribute to worldwide fallout.

The larger particles spill out of the stem and cascade down the outside

of the fireball in a downdraft even as the cloud rises, so fallout

begins to arrive near ground zero within an hour. More than half the total bomb debris lands on the ground within about 24 hours as local fallout.

Chemical properties of the elements in the fallout control the rate at

which they are deposited on the ground. Less volatile elements deposit

first.

Severe local fallout contamination can extend far beyond the

blast and thermal effects, particularly in the case of high yield

surface detonations. The ground track of fallout from an explosion

depends on the weather from the time of detonation onwards. In stronger

winds, fallout travels faster but takes the same time to descend, so

although it covers a larger path, it is more spread out or diluted.

Thus, the width of the fallout pattern for any given dose rate is

reduced where the downwind distance is increased by higher winds. The

total amount of activity deposited up to any given time is the same

irrespective of the wind pattern, so overall casualty figures from

fallout are generally independent of winds. But thunderstorms can bring down activity as rain allows fallout to drop more rapidly, particularly if the mushroom cloud is low enough to be below ("washout"), or mixed with ("rainout"), the thunderstorm.

Whenever individuals remain in a radiologically contaminated

area, such contamination leads to an immediate external radiation

exposure as well as a possible later internal hazard from inhalation and

ingestion of radiocontaminants, such as the rather short-lived iodine-131, which is accumulated in the thyroid.

Factors affecting fallout

Location

There

are two main considerations for the location of an explosion: height

and surface composition. A nuclear weapon detonated in the air, called

an air burst,

produces less fallout than a comparable explosion near the ground. A

nuclear explosion in which the fireball touches the ground pulls soil

and other materials into the cloud and neutron activates it before it

falls back to the ground. An air burst produces a relatively small

amount of the highly radioactive heavy metal components of the device

itself.

In case of water surface bursts, the particles tend to be rather

lighter and smaller, producing less local fallout but extending over a

greater area. The particles contain mostly sea salts with some water; these can have a cloud seeding effect causing local rainout and areas of high local fallout. Fallout from a seawater burst is difficult to remove once it has soaked into porous surfaces because the fission products are present as metallic ions

that chemically bond to many surfaces. Water and detergent washing

effectively removes less than 50% of this chemically bonded activity

from concrete or steel. Complete decontamination requires aggressive treatment like sandblasting, or acidic treatment. After the Crossroads

underwater test, it was found that wet fallout must be immediately

removed from ships by continuous water washdown (such as from the fire sprinkler system on the decks).

Parts of the sea bottom may become fallout. After the Castle Bravo test, white dust—contaminated calcium oxide particles originating from pulverized and calcined corals—fell for several hours, causing beta burns and radiation exposure to the inhabitants of the nearby atolls and the crew of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru fishing boat. The scientists called the fallout Bikini snow.

For subsurface bursts, there is an additional phenomenon present called "base surge".

The base surge is a cloud that rolls outward from the bottom of the

subsiding column, which is caused by an excessive density of dust or

water droplets in the air. For underwater bursts, the visible surge is,

in effect, a cloud of liquid (usually water) droplets with the property

of flowing almost as if it were a homogeneous fluid. After the water

evaporates, an invisible base surge of small radioactive particles may

persist.

For subsurface land bursts, the surge is made up of small solid particles, but it still behaves like a fluid.

A soil earth medium favors base surge formation in an underground

burst. Although the base surge typically contains only about 10% of the

total bomb debris in a subsurface burst, it can create larger radiation

doses than fallout near the detonation, because it arrives sooner than

fallout, before much radioactive decay has occurred.

Meteorological

Comparison

of fallout gamma dose and dose rate contours for a 1 Mt fission land

surface burst, based on DELFIC calculations. Because of radioactive

decay, the dose rate contours contract after fallout has arrived, but

dose contours continue to grow.

Meteorological

conditions greatly influence fallout, particularly local fallout.

Atmospheric winds are able to bring fallout over large areas. For

example, as a result of a Castle Bravo surface burst of a 15 Mt thermonuclear device at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954, a roughly cigar-shaped area of the Pacific

extending over 500 km downwind and varying in width to a maximum of

100 km was severely contaminated. There are three very different

versions of the fallout pattern from this test, because the fallout was

only measured on a small number of widely spaced Pacific Atolls. The two

alternative versions both ascribe the high radiation levels at north Rongelap

to a downwind hotspot caused by the large amount of radioactivity

carried on fallout particles of about 50–100 micrometres size.

After Bravo, it was discovered that fallout landing on the ocean disperses in the top water layer (above the thermocline

at 100 m depth), and the land equivalent dose rate can be calculated by

multiplying the ocean dose rate at two days after burst by a factor of

about 530. In other 1954 tests, including Yankee and Nectar, hotspots were mapped out by ships with submersible probes, and similar hotspots occurred in 1956 tests such as Zuni and Tewa. However, the major U.S. "DELFIC"

(Defence Land Fallout Interpretive Code) computer calculations use the

natural size distributions of particles in soil instead of the afterwind sweep-up spectrum, and this results in more straightforward fallout patterns lacking the downwind hotspot.

Snow and rain,

especially if they come from considerable heights, accelerate local

fallout. Under special meteorological conditions, such as a local rain

shower that originates above the radioactive cloud, limited areas of

heavy contamination just downwind of a nuclear blast may be formed.

Effects

A wide range of biological

changes may follow the irradiation of animals. These vary from rapid

death following high doses of penetrating whole-body radiation, to

essentially normal lives for a variable period of time until the

development of delayed radiation effects, in a portion of the exposed

population, following low dose exposures.

The unit of actual exposure is the röntgen, defined in ionisations per unit volume of air. All ionisation based instruments (including geiger counters and ionisation chambers)

measure exposure. However, effects depend on the energy per unit mass,

not the exposure measured in air. A deposit of 1 joule per kilogram has

the unit of 1 gray

(Gy). For 1 MeV energy gamma rays, an exposure of 1 röntgen in air

produces a dose of about 0.01 gray (1 centigray, cGy) in water or

surface tissue. Because of shielding by the tissue surrounding the

bones, the bone marrow

only receives about 0.67 cGy when the air exposure is 1 röntgen and the

surface skin dose is 1 cGy. Some lower values reported for the amount

of radiation that would kill 50% of personnel (the LD50) refer to bone marrow dose, which is only 67% of the air dose.

Short term

Fallout shelter sign on a building in New York City

The dose that would be lethal to 50% of a population is a common

parameter used to compare the effects of various fallout types or

circumstances. Usually, the term is defined for a specific time, and

limited to studies of acute lethality. The common time periods used are

30 days or less for most small laboratory animals and to 60 days for

large animals and humans. The LD50 figure assumes that the individuals did not receive other injuries or medical treatment.

In the 1950s, the LD50 for gamma rays was set at 3.5

Gy, while under more dire conditions of war (a bad diet, little medical

care, poor nursing) the LD50 was 2.5 Gy (250 rad). There have been few documented cases of survival beyond 6 Gy. One person at Chernobyl

survived a dose of more than 10 Gy, but many of the persons exposed

there were not uniformly exposed over their entire body. If a person is

exposed in a non-homogeneous manner then a given dose (averaged over the

entire body) is less likely to be lethal. For instance, if a person

gets a hand/low arm dose of 100 Gy, which gives them an overall dose of 4

Gy, they are more likely to survive than a person who gets a 4 Gy dose

over their entire body. A hand dose of 10 Gy or more would likely result

in loss of the hand. A British industrial radiographer who was estimated to have received a hand dose of 100 Gy over the course of his lifetime lost his hand because of radiation dermatitis. Most people become ill after an exposure to 1 Gy or more. The fetuses of pregnant women are often more vulnerable to radiation and may miscarry, especially in the first trimester.

One hour after a surface burst, the radiation from fallout in the crater region is 30 grays per hour (Gy/h). Civilian dose rates in peacetime range from 30 to 100 µGy per year.

Fallout radiation decays relatively quickly with time. Most areas

become fairly safe for travel and decontamination after three to five

weeks.

For yields of up to 10 kt,

prompt radiation is the dominant producer of casualties on the

battlefield. Humans receiving an acute incapacitating dose (30 Gy) have

their performance degraded almost immediately and become ineffective

within several hours. However, they do not die until five to six days

after exposure, assuming they do not receive any other injuries.

Individuals receiving less than a total of 1.5 Gy are not incapacitated.

People receiving doses greater than 1.5 Gy become disabled, and some

eventually die.

A dose of 5.3 Gy to 8.3 Gy is considered lethal but not

immediately incapacitating. Personnel exposed to this amount of

radiation have their cognitive performance degraded in two to three

hours,[12][13]

depending on how physically demanding the tasks they must perform are,

and remain in this disabled state at least two days. However, at that

point they experience a recovery period and can perform non-demanding

tasks for about six days, after which they relapse for about four weeks.

At this time they begin exhibiting symptoms of radiation poisoning

of sufficient severity to render them totally ineffective. Death

follows at approximately six weeks after exposure, although outcomes may

vary.

Long term

Comparison of predicted fallout "hotline" with test results in the 3.53 Mt 15% fission Zuni

test at Bikini in 1956. The predictions were made under simulated

tactical nuclear war conditions aboard ship by Edward A. Schuert.

Following the detonation of the first atomic bomb, pre-war steel

and post-war steel which is manufactured without atmospheric air,

became a valuable commodity for scientists wishing to make extremely

precise instruments that detect radioactive emissions, since these two

types of steel are the only steels that do not contain trace amounts of

fallout.

Late or delayed effects of radiation occur following a wide range of

doses and dose rates. Delayed effects may appear months to years after irradiation and include a wide variety of effects involving almost all tissues or organs. Some of the possible

delayed consequences of radiation injury, with the rates above the

background prevalence, depending on the absorbed dose, include carcinogenesis, cataract formation, chronic radiodermatitis, decreased fertility, and genetic mutations.

Presently, the only teratological effect observed in humans following nuclear attacks on highly populated areas is microcephaly which is the only proven malformation, or congenital abnormality, found in the in utero

developing human fetuses present during the Hiroshima and Nagasaki

bombings. Of all the pregnant women who were close enough to be exposed

to the prompt burst of intense neutron and gamma doses in the two cities, the total number of children born with microcephaly was below 50. No statistically demonstrable increase of congenital malformations was found among the later conceived children born to survivors of the nuclear detonations at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The surviving women of Hiroshima and Nagasaki who could conceive and

were exposed to substantial amounts of radiation went on and had

children with no higher incidence of abnormalities than the Japanese

average.

The Baby Tooth Survey founded by the husband and wife team of physicians Eric Reiss and Louise Reiss, was a research effort focused on detecting the presence of strontium-90, a cancer-causing

radioactive isotope created by the more than 400 atomic tests conducted

above ground that is absorbed from water and dairy products into the

bones and teeth given its chemical similarity to calcium. The team sent collection forms to schools in the St. Louis, Missouri

area, hoping to gather 50,000 teeth each year. Ultimately, the project

collected over 300,000 teeth from children of various ages before the

project was ended in 1970.

Preliminary results of the Baby Tooth Survey were published in the November 24, 1961, edition of the journal Science, and showed that levels of strontium 90 had risen steadily in children born in the 1950s, with those born later showing the most pronounced increases.

The results of a more comprehensive study of the elements found in the

teeth collected showed that children born after 1963 had levels of

strontium 90 in their baby teeth that was 50 times higher than that

found in children born before large-scale atomic testing began. The

findings helped convince U.S. President John F. Kennedy to sign the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the United Kingdom and Soviet Union, which ended the above-ground nuclear weapons testing that created the greatest amounts of atmospheric nuclear fallout.

The baby tooth survey was a "campaign [that] effectively employed

a variety of media advocacy strategies" to alarm the public and

"galvanized" support against atmospheric nuclear testing,

with putting an end to such testing being commonly viewed as a positive

outcome for a myriad of other reasons. The survey could not show then

at the time, nor in the decades that have elapsed, that the levels of

global strontium-90 or fallout in general, were in any way

life-threatening, primarily because "50 times the strontium-90 from before

nuclear testing" is a minuscule number, and multiplication of minuscule

numbers results in only a slightly larger minuscule number. Moreover,

the Radiation and Public Health Project which currently retains the teeth has had their stance and publications heavily criticized: A 2003 article in The New York Times states that the group's work has been controversial and has little credibility with the scientific establishment. Similarly, in an April 2014 article in Popular Science, Sarah Fecht explains that the group's work, specifically the widely discussed case of cherry-picking data to suggest that fallout from the 2011 Fukushima accident caused infant deaths in America, is "junk science",

as despite their papers being peer-reviewed, all independent attempts

to corroborate their results return findings that are not in agreement

with what the organization suggests. The organization had earlier also tried to suggest the same thing occurred after the 1979 Three Mile Island accident but this was likewise exposed to be without merit.

The tooth survey, and the expansion of the organization into attempting

the same test-ban approach with US nuclear electric power stations as

the new target, is likewise detailed and critically labelled as the "Tooth Fairy issue" by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Effects on the environment

In the event of a large-scale nuclear exchange, the effects would be

drastic on the environment as well as directly to the human population.

Within direct blast zones everything would be vaporized and destroyed.

Cities damaged but not completely destroyed would lose their water

system due to the loss of power and supply lines rupturing.

Within the local nuclear fallout pattern suburban areas' water supplies

would become extremely contaminated. At this point stored water would

be the only safe water to use. All surface water within the fallout

would be contaminated by falling fission products.

Within the first few months of the nuclear exchange the nuclear

fallout will continue to develop and detriment the environment. Dust,

smoke, and radioactive particles will fall hundreds of kilometers downwind of the explosion point and pollute surface water supplies. Iodine-131

would be the dominant fission product within the first few months, and

in the months following the dominant fission product would be strontium-90.

These fission products would remain in the fallout dust, resulting

rivers, lakes, sediments, and soils being contaminated with the fallout.

Rural areas' water supplies would be slightly less polluted by

fission particles in intermediate and long-term fallout than cities and

suburban areas. Without additional contamination, the lakes, reservoirs,

rivers, and runoff would be gradually less contaminated as water

continued to flow through its system.

Groundwater supplies such as aquifers would however remain

unpolluted initially in the event of a nuclear fallout. Over time the

groundwater could become contaminated with fallout particles, and would

remain contaminated for over 10 years after a nuclear engagement. It would take hundreds or thousands of years for an aquifer to become completely pure. Groundwater would still be safer than surface water supplies and would need to be consumed in smaller doses. Long term, cesium-137 and strontium-90 would be the major radionuclides affecting the fresh water supplies.

The dangers of nuclear fallout do not stop at increased risks of

cancer and radiation sickness, but also include the presence of

radionucleides in human organs from food. A fallout event would leave

fission particles in the soil for animals to consume, followed by

humans. Radioactively contaminated milk, meat, fish, vegetables, grains

and other food would all be dangerous because of fallout.

From 1945 to 1967 the U.S. conducted hundred of nuclear weapon tests. Atmospheric testing

took place over the US mainland during this time and as a consequence

scientists have been able to study the effect of nuclear fallout on the

environment. Detonations conducted near the surface of the earth

irradiated thousands of tons of soil.

Of the material drawn into the atmosphere, portions of radioactive

material will be carried by low altitude winds and deposited in

surrounding areas as radioactive dust. The material intercepted by high

altitude winds will continue to travel. When a radiation cloud at high

altitude is exposed to rainfall, the radioactive fallout will

contaminate the downwind area below.

Agricultural fields and plants will absorb the contaminated

material and animals will consume the radioactive material. As a result,

the nuclear fallout may cause livestock to become ill or die, and if

consumed the radioactive material will be passed on to humans.

The damage to other living organism as a result to nuclear fallout depends on the species.

Mammals particularly are extremely sensitive to nuclear radiation,

followed by birds, plants, fish, reptiles, crustaceans, insects, moss,

lichen, algae, bacteria, mollusks, and viruses.

Climatologist Alan Robock

and atmospheric and oceanic sciences professor Brian Toon created a

model of a hypothetical small-scale nuclear war that would have

approximately 100 weapons used. In this scenario, the fires would create

enough soot into the atmosphere to block sunlight, lowering global

temperatures by more than one degree Celsius. The result would have the potential of creating widespread food insecurity (nuclear famine).

Precipitation across the globe would be disrupted as a result. If

enough soot was introduced in the upper atmosphere the planet's ozone

layer could potentially be depleted, affecting plant growth and human

health.

Radiation from the fallout would linger in soil, plants, and food

chains for years. Marine food chains are more vulnerable to the nuclear

fallout and the effects of soot in the atmosphere.

Fallout radionuclides' detriment in the human food chain is apparent in the lichen-caribou-eskimo studies in Alaska. The primary effect on humans observed was thyroid dysfunction.

The result of a nuclear fallout is detrimental to human

survival and the biosphere. Fallout alters the quality of our

atmosphere, soil, and water and causes species to go extinct.

Fallout protection

During the Cold War,

the governments of the U.S., the USSR, Great Britain, and China

attempted to educate their citizens about surviving a nuclear attack by

providing procedures on minimizing short-term exposure to fallout. This

effort commonly became known as Civil Defense.

Fallout protection is almost exclusively concerned with

protection from radiation. Radiation from a fallout is encountered in

the forms of alpha, beta, and gamma radiation, and as ordinary clothing affords protection from alpha and beta radiation, most fallout protection measures deal with reducing exposure to gamma radiation. For the purposes of radiation shielding, many materials have a characteristic halving thickness:

the thickness of a layer of a material sufficient to reduce gamma

radiation exposure by 50%. Halving thicknesses of common materials

include: 1 cm (0.4 inch) of lead, 6 cm (2.4 inches) of concrete, 9 cm

(3.6 inches) of packed earth or 150 m (500 ft) of air. When multiple

thicknesses are built, the shielding is additive. A practical fallout

shield is ten halving-thicknesses of a given material, such as 90 cm

(36 inches) of packed earth, which reduces gamma ray exposure by

approximately 1024 times (210). A shelter built with these materials for the purposes of fallout protection is known as a fallout shelter.

Personal protective equipment

As

the nuclear energy sector continues to grow, the international rhetoric

surrounding nuclear warfare intensifies, and the ever-present threat of

radioactive materials falling into the hands of dangerous people

persists, many scientists are working hard to find the best way to

protect human organs from the harmful effects of high energy radiation. Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) is the most immediate risk to humans when exposed to ionizing radiation in dosages greater than around 0.1 Gy/hr. Radiation in the low energy spectrum (alpha and beta radiation) with minimal penetrating power is unlikely to cause significant damage to internal organs. The high penetrating power of gamma and neutron radiation,

however, easily penetrates the skin and many thin shielding mechanisms

to cause cellular degeneration in the stem cells found in bone marrow.

While full body shielding in a secure fallout shelter as described above

is the most optimal form of radiation protection, it requires being

locked in a very thick bunker for a significant amount of time. In the

event of a nuclear catastrophe of any kind, it is imperative to have mobile protection equipment

for medical and security personnel to perform necessary containment,

evacuation, and any number of other important public safety objectives.

The mass of the shielding material required to properly protect the

entire body from high energy radiation would make functional movement

essentially impossible. This has led scientists to begin researching the

idea of partial body protection: a strategy inspired by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

The idea is to use enough shielding material to sufficiently protect

the high concentration of bone marrow in the pelvic region, which

contains enough regenerative stem cells to repopulate the body with

unaffected bone marrow. More information on bone marrow shielding can be found in the Health Physics Radiation Safety Journal article Selective Shielding of Bone Marrow: An Approach to Protecting Humans from External Gamma Radiation, or in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA)'s 2015 report: Occupational Radiation Protection in Severe Accident Management.

The Seven Ten Rule

The

danger of radiation from fallout also decreases rapidly with time due

in large part to the exponential decay of the individual radionuclides.

A book by Cresson H. Kearny presents data showing that for the first

few days after the explosion, the radiation dose rate is reduced by a

factor of ten for every seven-fold increase in the number of hours since

the explosion. He presents data showing that "it takes about seven

times as long for the dose rate to decay from 1000 roentgens per hour

(1000 R/hr) to 10 R/hr (48 hours) as to decay from 1000 R/hr to 100 R/hr

(7 hours)." This is a fairly rough rule of thumb based on observed data, not a precise relation.

Government Guides to Fallout Protection in the 1960s

The United States government, often the Office of Civil Defense in the Department of Defense,

provided guides to fallout protection in the 1960s, frequently in the

form of booklets. These booklets provided information on how to best

survive nuclear fallout. They also included instructions for various fallout shelters, whether for a family, a hospital, or a school shelter were provided.

There were also instructions for how to create an improvised fallout

shelter, and what to do to best increase a person’s chances for survival

if they were unprepared.

The central idea in these guides is that materials like concrete,

dirt, and sand are necessary to shield a person from fallout particles

and radiation. A significant amount of materials of this type are

necessary to protect a person from fallout radiation, so safety clothing

cannot protect a person from fallout radiation.

However, protective clothing can keep fallout particles off a person’s

body, but the radiation from these particles will still permeate through

the clothing. For safety clothing to be able to block the fallout

radiation, it would have to be so thick and heavy that a person could

not function.

These guides indicated that fallout shelters should contain enough resources to keep its occupants alive for up to two weeks.

Community shelters were preferred over single-family shelters. The more

people in a shelter, the greater quantity and variety of resources that

shelter would be equipped with. These communities’ shelters would also

help facilitate efforts to recuperate the community in the future. Single family shelters should be built below ground if possible. Many different types of fallout shelters could be made for a relatively small amount of money. A common format for fallout shelters

was to build the shelter underground, with solid concrete blocks to act

as the roof. If a shelter could only be partially underground, it was

recommended to mound over that shelter with as much dirt as possible. If

a house had a basement, it is best for a fallout shelter to be constructed in a corner of the basement.

The center of a basement is where the most radiation will be because

the easiest way for radiation to enter a basement is from the floor

above.

The two of the walls of the shelter in a basement corner will be the

basement walls that are surrounded by dirt outside. Cinder blocks filled

with sand or dirt were highly recommended for the other two walls.

Concrete blocks, or some other dense material, should be used as a roof

for a basement fallout shelter because the floor of a house is not an

adequate roof for a fallout shelter. These shelters should contain water, food, tools, and a method for dealing with human waste.

If a person did not have a shelter previously built, these guides

recommended trying to get underground. If a person had a basement but

no shelter, they should put food, water, and a waste container in the

corner of the basement. Then items such as furniture should be piled up to create walls around the person in the corner.

The more things a person can surround themselves with the better. If

the underground cannot be reached, a tall apartment building at least

ten miles from the blast was recommended as a good fallout shelter.

People in these buildings should get as close to the center of the

building as possible and avoid the top and ground floors.

Once again, people should surround themselves with whatever they can

find and acquire whatever resources they can to create a barrier between

themselves and fallout particles and radiation.

During this time, schools were a favorable place to act as a fallout shelter according to the Office of Civil Defense.

For starters, schools, not including universities, contained

one-quarter of the population of the United States when they were in

session at that time.

Schools distribution across the nation reflected the density of the

population and were often a best building in a community to act as a

fallout shelter. Also, schools also already had organization with

leaders set in place. The Office of Civil Defense

recommended altering current schools and the construction of future

schools to include thicker walls and roofs, better protected electrical

systems, a purifying ventilation system, and a protected water pump. The Office of Civil Defense

determined 10 square feet of net area per person were necessary in

schools that were to function as a fallout shelter. A normal classroom

could provide 180 people with area to sleep. If an attack were to happen, all the unnecessary furniture was to be moved out of the classrooms to make more room for people. It was recommended to keep one or two tables in the room if possible to use as a food serving station.

The Office of Civil Defense

conducted four case studies to find the cost of turning four standing

schools into fallout shelters and what their capacity would be. The cost

of the schools per occupant in the 1960's were $66.00, $127.00, $50.00,

and $180.00. The capacity of people these schools could house as shelters were 735 ,511, 484, and 460 respectively.

Nuclear reactor accident

Fallout can also refer to nuclear accidents, although a nuclear reactor does not explode like a nuclear weapon. The isotopic signature of bomb fallout is very different from the fallout from a serious power reactor accident (such as Chernobyl or Fukushima).

The key differences are in volatility and half-life.

Volatility

The boiling point of an element (or its compounds)

is able to control the percentage of that element a power reactor

accident releases. The ability of an element to form a solid controls

the rate it is deposited on the ground after having been injected into

the atmosphere by a nuclear detonation or accident.

Half-life

A half life is the time it takes half of the radiation of a specific substance to decay. A large amount of short-lived isotopes such as 97Zr

are present in bomb fallout. This isotope and other short-lived

isotopes are constantly generated in a power reactor, but because the criticality occurs over a long length of time, the majority of these short lived isotopes decay before they can be released.

Preventative measures

Nuclear

fallout can occur due to a number of different sources. One of the most

common potential sources of nuclear fallout is that of nuclear reactors. Because of this, steps must be taken to ensure the risk of nuclear fallout at nuclear reactors is controlled.

In the 1950's and 60's, the United States Atomic Energy Commission

(AEC) began developing safety regulations against nuclear fallout for

civilian nuclear reactors. Because the effects of nuclear fallout are

more widespread and longer lasting than other forms of energy production

accidents, the AEC desired a more proactive response towards potential

accidents than ever before. One step to prevent nuclear reactor accidents was the Price-Anderson Act.

Passed by Congress in 1957, the Price-Anderson Act insured government

assistance above the $60 million covered by private insurance companies

in the case of a nuclear reactor accident. The main goal of the

Price-Anderson Act was to protect the multibillion-dollar companies

overseeing the production of nuclear reactors. Without this protection,

the nuclear reactor industry could potentially come to a halt, and the

protective measures against nuclear fallout would be reduced.

However, because of the limited experience in nuclear reactor

technology, engineers had a difficult time calculating the potential

risk of released radiation.

Engineers were forced to imagine every unlikely accident, and the

potential fallout associated with each accident. The AEC's regulations

against potential nuclear reactor fallout were centered on the ability

of the power plant to the Maximum Credible Accident, or MCA. The MCA

involved a "large release of radioactive isotopes after a substantial

meltdown of the reactor fuel when the reactor coolant system failed

through a Loss-of-Coolant Accident".

The prevention of the MCA enabled a number of new nuclear fallout

preventative measures. Static safety systems, or systems without power

sources or user input, were enabled to prevent potential human error.

Containment buildings, for example, were reliably effective at

containing a release of radiation and did not need to be powered or

turned on to operate. Active protective systems, although far less

dependable, can do many things that static systems cannot. For example, a

system to replace the escaping steam of a cooling system with cooling

water could prevent reactor fuel from melting. However, this system

would need a sensor to detect the presence of releasing steam. Sensors

can fail, and the results of a lack of preventative measures would

result in a local nuclear fallout. The AEC had to choose, then, between

active and static systems to protect the public from nuclear fallout.

With a lack of set standards and probabilistic calculations, the AEC and

the industry became divided on the best safety precautions to use.

This division gave rise to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission,

or NRC. The NRC was committed to 'regulations through research', which

gave the regulatory committee a knowledge bank of research on which to

draw their regulations. Much of the research done by the NRC sought to

move safety systems from a deterministic viewpoint into a new

probabilistic approach. The deterministic approach sought to foresee all

problems before they arose. The probabilistic approach uses a more

mathematical approach to weigh the risks of potential radiation leaks.

Much of the probabilistic safety approach can be drawn from the radiative transfer theory in Physics, which describes how radiation travels in free space and through barriers. Today, the NRC is still the leading regulatory committee on nuclear reactor power plants.

Determining extent of nuclear fallout

The International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale

(INES) is the primary form of categorizing the potential health and

environmental effects of a nuclear or radiological event and

communicating it to the public. The scale, which was developed in 1990 by the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Nuclear Energy Agency of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, classifies these nuclear accidents based off the potential impact of the fallout:

- Defence-in-Depth: This is the lowest form of nuclear accidents and refers to events that have no direct impact on people or the environment but must be taken note of to improve future safety measures.

- Radiological Barriers and Control: This category refers to events that have no direct impact on people or the environment and only refer to the damage caused within major facilities.

- People and the Environment: This section of the scale comprises of more serious nuclear accidents. Events in this category could potentially cause radiation to spread to people close to the location of the accident. This also includes an unplanned, widespread release of the radioactive material.

The INES scale is composed of seven steps that categorize the nuclear

events, ranging from anomalies that must be recorded to improve upon

safety measures to serious accidents that require immediate action.

Chernobyl

The 1986 nuclear reactor explosion at Chernobyl

was categorized as a Level 7 accident, which is the highest possible

ranking on the INES scale, due to widespread environmental and health

effects and “external release of a significant fraction of reactor core

inventory”. The nuclear accident still stands as the only accident in commercial nuclear power that led to radiation-related deaths. The steam explosion and fires released approximately 5200 PBq, or at least 5 percent of the reactor core, into the atmosphere.

The explosion itself resulted in the deaths of two plant workers, while

28 people died over the weeks that followed of severe radiation

poisoning.

Furthermore, young children and adolescents in the areas most

contaminated by the radiation exposure showed an increase in the risk

for thyroid cancer, although the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation stated that "there is no evidence of a major public health impact" apart from that.

The nuclear accident also took a heavy toll on the environment,

including contamination in urban environments caused by the deposition

of radionuclides and the contamination of “different crop types, in

particular, green leafy vegetables … depending on the deposition levels,

and time of the growing season”.

Three Mile Island

The nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island

in 1979 was categorized as a Level 5 accident on the INES scale because

of the “severe damage to the reactor core” and the radiation leak

caused by the incident.

The explosion was the most serious accident in the history of American

commercial nuclear power plants, yet the effects were different than

that of the Chernobyl accident. A study done by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

following the incident reveals that the nearly 2 million people

surrounding the Three Mile Island plant “are estimated to have received

an average radiation dose of only 1 millirem above the usual background

dose”.

Furthermore, unlike those affected by radiation in the Chernobyl

accident, the development of thyroid cancer in the people around Three

Mile Island was “less aggressive and less advanced”.

Fukushima

Like the Three Mile Island incident, the incident at Fukushima

was initially categorized as a Level 5 accident on the INES scale after

a tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of three reactors,

which then suffered significant melting in the days that followed.

However, after combining the accidents on the three reactors rather

than assessing them as individual events, the explosion was upgraded to a

Level 7 accident. The radiation exposure from the incident caused a recommended evacuation for inhabitants up to 30 km away from the plant.

However, it was also hard to track such exposure because 23 out of the

24 radioactive monitoring stations were also disabled by the tsunami.

Removing contaminated water, both in the plant itself and run-off water

that spread into the sea and nearby areas, became a huge challenge for

the Japanese government and plant workers. During the containment period

following the accident, thousands of cubic meters of slightly

contaminated water were released in the sea to free up storage for more

contaminated water in the reactor and turbine buildings. However, the fallout from the Fukushima accident had a minimal impact on the surrounding population. According to the Institut de Radioprotection et de Surêté Nucléaire,

over 62 percent of assessed residents within the Fukushima prefecture

received external doses of less than 1 mSv in the four months following

the accident.

In addition, comparing screening campaigns for children inside the

Fukushima prefecture and in the rest of the country revealed no

significant difference in the risk of thyroid cancer.

International nuclear safety standards

Founded in 1974, the International Atomic Energy Agency

(IAEA) was created to set forth international standards for nuclear

reactor safety. However, without a proper policing force, the guidelines

set forth by the IAEA were often treated lightly or ignored completely.

In 1986, the disaster at Chernobyl was evidence that international nuclear reactor safety was not to be taken lightly. Even in the midst of the Cold War, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission sought to improve the safety of Soviet nuclear reactors. As noted by IAEA Director General Hans Blix, "A radiation cloud doesn't know international boundaries."

The NRC showed the Soviets the safety guidelines used in the US:

capable regulation, safety-minded operations, and effective plant

designs. The soviets, however, had their own priority: keeping the plant

running at all costs. In the end, the same shift between deterministic

safety designs to probabilistic safety designs prevailed. In 1989, the World Association of Nuclear Operators

(WANO) was formed to cooperate with the IAEA to ensure the same three

pillars of reactor safety across international borders. In 1991, WANO

concluded (using a probabilistic safety approach) that all former

communist-controlled nuclear reactors could not be trusted, and should

be closed. Compared to a "Nuclear Marshall Plan", efforts were taken throughout the 1990s and 2000s to ensure international standards of safety for all nuclear reactors.