From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Clinical psychology is an integration of science, theory, and

clinical knowledge for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and

relieving psychologically-based distress or

dysfunction and to promote subjective

well-being and personal development. Central to its practice are

psychological assessment,

clinical formulation, and

psychotherapy,

although clinical psychologists also engage in research, teaching,

consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and

administration. In many countries, clinical psychology is a regulated

mental health profession.

The field is generally considered to have begun in 1896 with the opening of the first psychological

clinic at the

University of Pennsylvania by

Lightner Witmer.

In the first half of the 20th century, clinical psychology was focused

on psychological assessment, with little attention given to treatment.

This changed after the 1940s when World War II resulted in the need for a

large increase in the number of trained clinicians. Since that time,

three main educational models have developed in the USA—the Ph.D.

Clinical Science model (heavily focused on research), the

Ph.D. science-practitioner model (integrating research and practice), and the

Psy.D. practitioner-scholar model (focusing on clinical practice). In the UK and the Republic of Ireland, the

Clinical Psychology Doctorate

falls between the latter two of these models, whilst in much of

mainland Europe, the training is at the masters level and predominantly

psychotherapeutic. Clinical psychologists are expert in providing

psychotherapy, and generally train within four primary theoretical

orientations—

psychodynamic,

humanistic,

cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and

systems or family therapy.

History

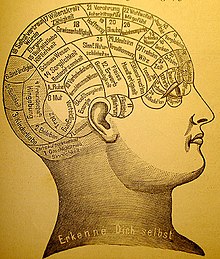

Many 18th c. treatments for psychological distress were based on pseudo-scientific ideas, such as Phrenology.

The earliest recorded approaches to assess and treat mental distress

were a combination of religious, magical and/or medical perspectives. Early examples of such physicians included

Patañjali,

Padmasambhava,

Rhazes,

Avicenna, and

Rumi. In the early 19th century, one approach to study mental conditions and behavior was using

phrenology,

the study of personality by examining the shape of the skull. Other

popular treatments at that time included the study of the shape of the

face (

physiognomy) and

Mesmer's treatment for mental conditions using magnets (

mesmerism).

Spiritualism and

Phineas Quimby's "mental healing" were also popular.

While the scientific community eventually came to reject all of

these methods for treating mental illness, academic psychologists also

were not concerned with serious forms of mental illness. The study of

mental illness was already being done in the developing fields of

psychiatry and

neurology within the

asylum movement. It was not until the end of the 19th century, around the time when

Sigmund Freud was first developing his "

talking cure" in

Vienna, that the first scientific application of clinical psychology began.

Early clinical psychology

Cover of The Psychological Clinic, the first journal of clinical psychology, published in 1907 by Lightner Witmer

By the second half of the 1800s, the scientific study of psychology

was becoming well established in university laboratories. Although there

were a few scattered voices calling for applied psychology, the general

field looked down upon this idea and insisted on "pure" science as the

only respectable practice.

[5] This changed when

Lightner Witmer (1867–1956), a past student of

Wundt and head of the psychology department at the

University of Pennsylvania,

agreed to treat a young boy who had trouble with spelling. His

successful treatment was soon to lead to Witmer's opening of the first

psychological clinic at Penn in 1896, dedicated to helping children with

learning disabilities. Ten years later in 1907, Witmer was to found the first journal of this new field,

The Psychological Clinic,

where he coined the term "clinical psychology", defined as "the study

of individuals, by observation or experimentation, with the intention of

promoting change". The field was slow to follow Witmer's example, but by 1914, there were 26 similar clinics in the U.S.

Even as clinical psychology was growing, working with issues of serious mental distress remained the domain of

psychiatrists and

neurologists. However, clinical psychologists continued to make inroads into this area due to their increasing skill at

psychological assessment. Psychologists' reputation as assessment experts became solidified during

World War I with the development of two intelligence tests,

Army Alpha and

Army Beta (testing verbal and nonverbal skills, respectively), which could be used with large groups of recruits.

Due in large part to the success of these tests, assessment was to

become the core discipline of clinical psychology for the next quarter

century, when another war would propel the field into treatment.

Early professional organizations

The

field began to organize under the name "clinical psychology" in 1917

with the founding of the American Association of Clinical Psychology.

This only lasted until 1919, after which the

American Psychological Association (founded by

G. Stanley Hall in 1892) developed a section on Clinical Psychology, which offered certification until 1927.

Growth in the field was slow for the next few years when various

unconnected psychological organizations came together as the American

Association of Applied Psychology in 1930, which would act as the

primary forum for psychologists until after World War II when the APA

reorganized.

In 1945, the APA created what is now called Division 12, its division

of clinical psychology, which remains a leading organization in the

field. Psychological societies and associations in other

English-speaking countries developed similar divisions, including in

Britain, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

World War II and the integration of treatment

When

World War II

broke out, the military once again called upon clinical psychologists.

As soldiers began to return from combat, psychologists started to notice

symptoms of psychological trauma labeled "shell shock" (eventually to

be termed

posttraumatic stress disorder) that were best treated as soon as possible.

Because physicians (including psychiatrists) were over-extended in

treating bodily injuries, psychologists were called to help treat this

condition.

At the same time, female psychologists (who were excluded from the war

effort) formed the National Council of Women Psychologists with the

purpose of helping communities deal with the stresses of war and giving

young mothers advice on child rearing. After the war, the

Veterans Administration

in the U.S. made an enormous investment to set up programs to train

doctoral-level clinical psychologists to help treat the thousands of

veterans needing care. As a consequence, the U.S. went from having no

formal university programs in clinical psychology in 1946 to over half

of all Ph.D.s in psychology in 1950 being awarded in clinical

psychology.

WWII helped bring dramatic changes to clinical psychology, not

just in America but internationally as well. Graduate education in

psychology began adding psychotherapy to the science and research focus

based on the 1947

scientist-practitioner model, known today as the

Boulder Model, for Ph.D. programs in clinical psychology. Clinical psychology in

Britain developed much like in the U.S. after WWII, specifically within the context of the

National Health Service with qualifications, standards, and salaries managed by the

British Psychological Society.

Development of the Doctor of Psychology degree

By

the 1960s, psychotherapy had become embedded within clinical

psychology, but for many, the Ph.D. educational model did not offer the

necessary training for those interested in practice rather than

research. There was a growing argument that said the field of psychology

in the U.S. had developed to a degree warranting explicit training in

clinical practice. The concept of a practice-oriented degree was debated

in 1965 and narrowly gained approval for a pilot program at the

University of Illinois starting in 1968. Several other similar programs were instituted soon after, and in 1973, at the

Vail Conference on Professional Training in Psychology, the

practitioner–scholar model of clinical psychology—or

Vail Model—resulting in the Doctor of Psychology (

Psy.D.) degree was recognized.

Although training would continue to include research skills and a

scientific understanding of psychology, the intent would be to produce

highly trained professionals, similar to programs in medicine,

dentistry, and law. The first program explicitly based on the Psy.D.

model was instituted at

Rutgers University. Today, about half of all American graduate students in clinical psychology are enrolled in Psy.D. programs.

A changing profession

Since

the 1970s, clinical psychology has continued growing into a robust

profession and academic field of study. Although the exact number of

practicing clinical psychologists is unknown, it is estimated that

between 1974 and 1990, the number in the U.S. grew from 20,000 to

63,000.

Clinical psychologists continue to be experts in assessment and

psychotherapy while expanding their focus to address issues of

gerontology, sports, and the criminal justice system to name a few. One

important field is

health psychology, the fastest-growing employment setting for clinical psychologists in the past decade. Other major changes include the impact of

managed care

on mental health care; an increasing realization of the importance of

knowledge relating to multicultural and diverse populations; and

emerging privileges to prescribe psychotropic medication.

Professional practice

Clinical psychologists engage in a wide range of activities. Some focus solely on

research into the

assessment,

treatment, or cause of

mental illness and related conditions. Some teach, whether in a

medical school or

hospital setting, or in an academic department (e.g., psychology department) at an

institution of higher education.

The majority of clinical psychologists engage in some form of clinical

practice, with professional services including psychological assessment,

provision of psychotherapy, development and administration of clinical

programs, and

forensics (e.g., providing expert testimony in a

legal proceeding).

In clinical practice, clinical psychologists may work with

individuals, couples, families, or groups in a variety of settings,

including private practices, hospitals, mental health organizations,

schools, businesses, and non-profit agencies. Clinical psychologists who

provide clinical services may also choose to specialize. Some

specializations are codified and credentialed by regulatory agencies

within the country of practice. In the United States such specializations are credentialed by the

American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP).

Training and certification to practice

Clinical

psychologists study a generalist program in psychology plus

postgraduate training and/or clinical placement and supervision. The

length of training differs across the world, ranging from four years

plus post-Bachelors supervised practice to a doctorate of three to six years which combines clinical placement. In the USA, about half of all clinical psychology graduate students are being trained in

Ph.D. programs—a model that emphasizes research—with the other half in

Psy.D. programs, which has more focus on practice (similar to professional degrees for medicine and law). Both models are accredited by the

American Psychological Association

and many other English-speaking psychological societies. A smaller

number of schools offer accredited programs in clinical psychology

resulting in a

Masters degree, which usually take two to three years post-Bachelors.

In the U.K., clinical psychologists undertake a Doctor of Clinical Psychology (D.Clin.Psych.), which is a practitioner

doctorate with both clinical and research components. This is a three-year full-time salaried program sponsored by the

National Health Service

(NHS) and based in universities and the NHS. Entry into these programs

is highly competitive and requires at least a three-year undergraduate

degree in psychology plus some form of experience, usually in either the

NHS as an Assistant Psychologist or in academia as a Research

Assistant. It is not unusual for applicants to apply several times

before being accepted onto a training course as only about one-fifth of

applicants are accepted each year. These clinical psychology doctoral degrees are accredited by the

British Psychological Society and the Health Professions Council (

HPC). The

HPC

is the statutory regulator for practitioner psychologists in the UK.

Those who successfully complete clinical psychology doctoral degrees are

eligible to apply for registration with the HPC as a clinical

psychologist.

The practice of clinical psychology requires a license in the

United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and many other countries.

Although each of the U.S. states is somewhat different in terms of

requirements and licenses, there are three common elements:

- Graduation from an accredited school with the appropriate degree

- Completion of supervised clinical experience or internship

- Passing a written examination and, in some states, an oral examination

All U.S. state and Canadian province licensing boards are members of

the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB) which

created and maintains the Examination for Professional Practice in

Psychology (EPPP). Many states require other examinations in addition to

the EPPP, such as a jurisprudence (i.e. mental health law) examination

and/or an oral examination.

Most states also require a certain number of continuing education

credits per year in order to renew a license, which can be obtained

through various means, such as taking audited classes and attending

approved workshops. Clinical psychologists require the Psychologist

license to practice, although licenses can be obtained with a

masters-level degree, such as Marriage and Family Therapist (MFT),

Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC), and Licensed Psychological Associate (LPA).

In the U.K. registration as a clinical psychologist with the Health Professions Council

(HPC) is necessary. The

HPC

is the statutory regulator for practitioner psychologists in the U.K.

In the U.K. the following titles are restricted by law "registered

psychologist" and "practitioner psychologist"; in addition, the

specialist title "clinical psychologist" is also restricted by law.

Assessment

An important area of expertise for many clinical psychologists is

psychological assessment, and there are indications that as many as 91% of

psychologists engage in this core clinical practice. Such evaluation is usually done in service to gaining insight into and forming

hypotheses

about psychological or behavioral problems. As such, the results of

such assessments are usually used to create generalized impressions

(rather than

diagnoses)

in service to informing treatment planning. Methods include formal

testing measures, interviews, reviewing past records, clinical

observation, and physical examination.

Measurement domains

There exist hundreds of various assessment tools, although only a few have been shown to have both high

validity (i.e., test actually measures what it claims to measure) and

reliability (i.e., consistency). These measures generally fall within one of several categories, including the following:

- Intelligence & achievement tests – These tests are designed to measure certain specific kinds of cognitive functioning (often referred to as IQ) in comparison to a norming group. These tests, such as the WISC-IV,

attempt to measure such traits as general knowledge, verbal skill,

memory, attention span, logical reasoning, and visual/spatial

perception. Several tests have been shown to predict accurately certain

kinds of performance, especially scholastic.

- Personality tests – Tests of personality aim to describe patterns of behavior, thoughts, and feelings. They generally fall within two categories: objective and projective. Objective measures, such as the MMPI,

are based on restricted answers—such as yes/no, true/false, or a rating

scale—which allow for the computation of scores that can be compared to

a normative group. Projective tests, such as the Rorschach inkblot test, allow for open-ended answers, often based on ambiguous stimuli.

- Neuropsychological tests – Neuropsychological tests consist of specifically designed tasks used to measure psychological functions known to be linked to a particular brain structure or pathway. They are typically used to assess impairment after an injury or illness known to affect neurocognitive functioning, or when used in research, to contrast neuropsychological abilities across experimental groups.

- Clinical observation – Clinical psychologists are also

trained to gather data by observing behavior. The clinical interview is a

vital part of the assessment, even when using other formalized tools,

which can employ either a structured or unstructured format. Such

assessment looks at certain areas, such as general appearance and

behavior, mood and affects, perception, comprehension, orientation,

insight, memory, and content of the communication. One psychiatric

example of a formal interview is the mental status examination, which is often used in psychiatry as a screening tool for treatment or further testing.

Diagnostic impressions

Several new models are being discussed, including a "dimensional

model" based on empirically validated models of human differences (such

as the

five factor model of personality) and a "psychosocial model", which would take changing, intersubjective states into greater account.

The proponents of these models claim that they would offer greater

diagnostic flexibility and clinical utility without depending on the

medical concept of illness.

However, they also admit that these models are not yet robust enough to

gain widespread use, and should continue to be developed.

Clinical psychologists do not tend to diagnose, but rather use

formulation—an

individualized map of the difficulties that the patient or client

faces, encompassing predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating

(maintaining) factors.

Clinical v. mechanical prediction

Clinical assessment can be characterized as a

prediction problem where the purpose of assessment is to make inferences (predictions) about past, present, or future behavior. For example, many

therapy decisions are made on the basis of what a

clinician expects will help a patient make therapeutic gains. Once observations have been collected (e.g.,

psychological test results, diagnostic impressions, clinical history,

X-ray, etc.), there are two mutually exclusive ways to combine those sources of information to arrive at a decision,

diagnosis, or prediction. One way is to combine the data in an

algorithmic,

or "mechanical" fashion. Mechanical prediction methods are simply a

mode of combination of data to arrive at a decision/prediction of

behavior (e.g.,

treatment response).

The mechanical prediction does not preclude any type of data from being

combined; it can incorporate clinical judgments, properly coded, in the

algorithm.

The defining characteristic is that, once the data to be combined is

given, the mechanical approach will make a prediction that is 100%

reliable.

That is, it will make exactly the same prediction for exactly the same

data every time. Clinical prediction, on the other hand, does not

guarantee this, as it depends on the

decision-making processes of the clinician making the judgment, their current state of mind, and knowledge base.

What has come to be called the "clinical versus statistical prediction" debate was first described in detail in 1954 by

Paul Meehl,

where he explored the claim that mechanical (formal, algorithmic)

methods of data combination could outperform clinical (e.g., subjective,

informal, "in the clinician's head") methods when such combinations are

used to arrive at a prediction of behavior. Meehl concluded that

mechanical modes of combination performed as well or better than

clinical modes. Subsequent

meta-analyses of studies that directly compare mechanical and clinical predictions have born out Meehl's 1954 conclusions. A 2009 survey of practicing

clinical psychologists found that clinicians almost exclusively use their clinical judgment to make behavioral predictions for their

patients, including

diagnosis and

prognosis.

Intervention

Psychotherapy involves a formal relationship between professional and

client—usually an individual, couple, family, or small group—that

employs a set of procedures intended to form a therapeutic alliance,

explore the nature of psychological problems, and encourage new ways of

thinking, feeling, or behaving.

Clinicians have a wide range of individual interventions to draw

from, often guided by their training—for example, a cognitive behavioral

therapy (

CBT) clinician might use worksheets to record distressing cognitions, a

psychoanalyst might encourage

free association, while a psychologist trained in

Gestalt

techniques might focus on immediate interactions between client and

therapist. Clinical psychologists generally seek to base their work on

research evidence and outcome studies as well as on trained clinical

judgment. Although there are literally dozens of recognized therapeutic

orientations, their differences can often be categorized on two

dimensions: insight vs. action and in-session vs. out-session.

- Insight – emphasis is on gaining a greater understanding of the

motivations underlying one's thoughts and feelings (e.g. psychodynamic

therapy)

- Action – focus is on making changes in how one thinks and acts (e.g. solution focused therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy)

- In-session – interventions center on the here-and-now interaction

between client and therapist (e.g. humanistic therapy, Gestalt therapy)

- Out-session – a large portion of therapeutic work is intended to

happen outside of session (e.g. bibliotherapy, rational emotive behavior

therapy)

The methods used are also different in regards to the population

being served as well as the context and nature of the problem. Therapy

will look very different between, say, a traumatized child, a depressed

but high-functioning adult, a group of people recovering from substance

dependence, and a ward of the state suffering from terrifying delusions.

Other elements that play a critical role in the process of

psychotherapy include the environment, culture, age, cognitive

functioning, motivation, and duration (i.e. brief or long-term therapy).

Four main schools

Many clinical psychologists are

integrative or

eclectic

and draw from the evidence base across different models of therapy in

an integrative way, rather than using a single specific model.

In the UK, clinical psychologists have to show competence in at

least two models of therapy, including CBT, to gain their doctorate. The

British Psychological Society

Division of Clinical Psychology has been vocal about the need to follow

the evidence base rather than being wedded to a single model of

therapy.

Psychodynamic

The psychodynamic perspective developed out of the

psychoanalysis of

Sigmund Freud.

The core object of psychoanalysis is to make the unconscious

conscious—to make the client aware of his or her own primal drives

(namely those relating to sex and aggression) and the various

defenses used to keep them in check. The essential tools of the psychoanalytic process are the use of

free association and an examination of the client's

transference

towards the therapist, defined as the tendency to take unconscious

thoughts or emotions about a significant person (e.g. a parent) and

"transfer" them onto another person. Major variations on Freudian

psychoanalysis practiced today include

self psychology,

ego psychology, and

object relations theory. These general orientations now fall under the umbrella term

psychodynamic psychology,

with common themes including examination of transference and defenses,

an appreciation of the power of the unconscious, and a focus on how

early developments in childhood have shaped the client's current

psychological state.

Humanistic

Humanistic psychology was developed in the 1950s in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis, largely due to the

person-centered therapy of

Carl Rogers (often referred to as Rogerian Therapy) and

existential psychology developed by

Viktor Frankl and

Rollo May.

Rogers believed that a client needed only three things from a clinician

to experience therapeutic improvement—congruence, unconditional

positive regard, and empathetic understanding. By using

phenomenology,

intersubjectivity

and first-person categories, the humanistic approach seeks to get a

glimpse of the whole person and not just the fragmented parts of the

personality.

This aspect of holism links up with another common aim of humanistic

practice in clinical psychology, which is to seek an integration of the

whole person, also called

self-actualization. From 1980,

Hans-Werner Gessmann integrated the ideas of humanistic psychology into group psychotherapy as

humanistic psychodrama. According to humanistic thinking,

each individual person already has inbuilt potentials and resources

that might help them to build a stronger personality and self-concept.

The mission of the humanistic psychologist is to help the individual

employ these resources via the therapeutic relationship.

Behavioral and cognitive behavioral

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) developed from the combination of

cognitive therapy and

rational emotive behavior therapy, both of which grew out of

cognitive psychology and

behaviorism.

CBT is based on the theory that how we think (cognition), how we feel

(emotion), and how we act (behavior) are related and interact together

in complex ways. In this perspective, certain dysfunctional ways of

interpreting and appraising the world (often through

schemas or

beliefs)

can contribute to emotional distress or result in behavioral problems.

The object of many cognitive behavioral therapies is to discover and

identify the biased, dysfunctional ways of relating or reacting and

through different methodologies help clients transcend these in ways

that will lead to increased well-being. There are many techniques used, such as

systematic desensitization,

socratic questioning,

and keeping a cognition observation log. Modified approaches that fall

into the category of CBT have also developed, including

dialectic behavior therapy and

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Behavior therapy is a rich tradition. It is well researched with a strong evidence base. Its roots are in

behaviorism.

In behavior therapy, environmental events predict the way we think and

feel. Our behavior sets up conditions for the environment to feedback

back on it. Sometimes the feedback leads the behavior to increase-

reinforcement and sometimes the behavior decreases- punishment.

Oftentimes behavior therapists are called

applied behavior analysts or behavioral health counselors. They have studied many areas from developmental disabilities to

depression and

anxiety disorders.

In the area of mental health and addictions a recent article looked at

APA's list for well established and promising practices and found a

considerable number of them based on the principles of operant and

respondent conditioning. Multiple assessment techniques have come from this approach including

functional analysis (psychology),

which has found a strong focus in the school system. In addition,

multiple intervention programs have come from this tradition including

community reinforcement approach for treating addictions,

acceptance and commitment therapy,

functional analytic psychotherapy, including

dialectic behavior therapy and

behavioral activation. In addition, specific techniques such as

contingency management and

exposure therapy have come from this tradition.

Systems or family therapy

Systems or

family therapy

works with couples and families, and emphasizes family relationships as

an important factor in psychological health. The central focus tends to

be on interpersonal dynamics, especially in terms of how change in one

person will affect the entire system.

Therapy is therefore conducted with as many significant members of the

"system" as possible. Goals can include improving communication,

establishing healthy roles, creating alternative narratives, and

addressing problematic behaviors.

Other therapeutic perspectives

There exist dozens of recognized schools or orientations of

psychotherapy—the list below represents a few influential orientations

not given above. Although they all have some typical set of techniques

practitioners employ, they are generally better known for providing a

framework of theory and philosophy that guides a therapist in his or her

working with a client.

- Existential – Existential psychotherapy

postulates that people are largely free to choose who we are and how we

interpret and interact with the world. It intends to help the client

find deeper meaning in life and to accept responsibility for living. As

such, it addresses fundamental issues of life, such as death, aloneness,

and freedom. The therapist emphasizes the client’s ability to be

self-aware, freely make choices in the present, establish personal

identity and social relationships, create meaning, and cope with the

natural anxiety of living.

- Gestalt - Gestalt therapy was primarily founded by Fritz Perls

in the 1950s. This therapy is perhaps best known for using techniques

designed to increase self-awareness, the best-known perhaps being the

"empty chair technique." Such techniques are intended to explore

resistance to "authentic contact", resolve internal conflicts, and help

the client complete "unfinished business".

- Postmodern – Postmodern psychology says that the experience

of reality is a subjective construction built upon language, social

context, and history, with no essential truths.

Since "mental illness" and "mental health" are not recognized as

objective, definable realities, the postmodern psychologist instead sees

the goal of therapy strictly as something constructed by the client and

therapist. Forms of postmodern psychotherapy include narrative therapy, solution-focused therapy, and coherence therapy.

- Transpersonal – The transpersonal perspective places a stronger focus on the spiritual facet of human experience. It is not a set of techniques so much as a willingness to help a client explore spirituality and/or transcendent states of consciousness. It also is concerned with helping clients achieve their highest potential.

- Multiculturalism – Although the theoretical foundations of

psychology are rooted in European culture, there is a growing

recognition that there exist profound differences between various ethnic

and social groups and that systems of psychotherapy need to take those

differences into greater consideration.

Further, the generations following immigrant migration will have some

combination of two or more cultures—with aspects coming from the parents

and from the surrounding society—and this process of acculturation

can play a strong role in therapy (and might itself be the presenting

problem). Culture influences ideas about change, help-seeking, locus of

control, authority, and the importance of the individual versus the

group, all of which can potentially clash with certain givens in

mainstream psychotherapeutic theory and practice.

As such, there is a growing movement to integrate knowledge of various

cultural groups in order to inform therapeutic practice in a more

culturally sensitive and effective way.

- Feminism – Feminist therapy

is an orientation arising from the disparity between the origin of most

psychological theories (which have male authors) and the majority of

people seeking counseling being female. It focuses on societal,

cultural, and political causes and solutions to issues faced in the

counseling process. It openly encourages the client to participate in

the world in a more social and political way.

- Positive psychology – Positive psychology is the scientific study of human happiness and well-being, which started to gain momentum in 1998 due to the call of Martin Seligman, then president of the APA. The history of psychology shows that the field has been primarily dedicated to addressing mental illness

rather than mental wellness. Applied positive psychology's main focus,

therefore, is to increase one's positive experience of life and ability

to flourish by promoting such things as optimism about the future, a

sense of flow in the present, and personal traits like courage,

perseverance, and altruism.

There is now preliminary empirical evidence to show that by promoting

Seligman's three components of happiness—positive emotion (the pleasant

life), engagement (the engaged life), and meaning (the meaningful

life)—positive therapy can decrease clinical depression.

Integration

In the last couple of decades, there has been a growing movement to

integrate the various therapeutic approaches, especially with an

increased understanding of cultural, gender, spiritual, and

sexual-orientation issues. Clinical psychologists are beginning to look

at the various strengths and weaknesses of each orientation while also

working with related fields, such as

neuroscience,

behavioral genetics,

evolutionary biology, and

psychopharmacology.

The result is a growing practice of eclecticism, with psychologists

learning various systems and the most efficacious methods of therapy

with the intent to provide the best solution for any given problem.

Professional ethics

The field of clinical psychology in most countries is strongly

regulated by a code of ethics. In the U.S., professional ethics are

largely defined by the APA Code of Conduct, which is often used

by states to define licensing requirements. The APA Code generally sets a

higher standard than that which is required by law as it is designed to

guide responsible behavior, the protection of clients, and the

improvement of individuals, organizations, and society. The Code is applicable to all psychologists in both research and applied fields.

The APA Code is based on five principles: Beneficence and

Nonmaleficence, Fidelity and Responsibility, Integrity, Justice, and

Respect for People's Rights and Dignity.

Detailed elements address how to resolve ethical issues, competence,

human relations, privacy and confidentiality, advertising, record

keeping, fees, training, research, publication, assessment, and therapy.

In the UK the

British Psychological Society

has published a Code of Conduct and Ethics for clinical psychologists.

This has four key areas: Respect, Competence, Responsibility and

Integrity. Other European professional organisations have similar codes of conduct and ethics.

Comparison with other mental health professions

Psychiatry

Although clinical psychologists and

psychiatrists

can be said to share a same fundamental aim—the alleviation of mental

distress—their training, outlook, and methodologies are often quite

different. Perhaps the most significant difference is that psychiatrists

are licensed physicians. As such, psychiatrists often use the

medical model to assess psychological problems (i.e., those they treat are seen as patients with an illness) and rely on

psychotropic medications as the chief method of addressing the illness—although many also employ

psychotherapy as well. Psychiatrists and

medical psychologists

(who are clinical psychologists that are also licensed to prescribe)

are able to conduct physical examinations, order and interpret

laboratory tests and

EEGs, and may order brain imaging studies such as

CT or

CAT,

MRI, and

PET scanning.

Clinical psychologists generally do not

prescribe medication, although there is a growing movement for psychologists to have

prescribing privileges. These medical privileges require additional training and education. To date,

medical psychologists

may prescribe psychotropic medications in Guam, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois,

New Mexico, Louisiana, the Public Health Service, the Indian Health

Service, and the United States Military.

Counseling psychology

Counseling psychologists

undergo the same level of rigor in study and use many of the same

interventions and tools as clinical psychologists, including

psychotherapy and assessment. Traditionally, counseling psychologists

helped people with what might be considered normal or moderate

psychological problems—such as the feelings of anxiety or sadness

resulting from major life changes or events.

However, that distinction has faded over time, and of the counseling

psychologists who do not go into academia (which does not involve

treatment or diagnosis), the majority of counseling psychologists treat

mental illness alongside clinical psychologists. Many counseling

psychologists also receive specialized training in career assessment,

group therapy, and relationship counseling.

Counseling psychology as a field values multiculturalism

and social advocacy, often stimulating research in multicultural

issues. There are fewer counseling psychology graduate programs than

those for clinical psychology and they are more often housed in

departments of education rather than psychology. Counseling

psychologists tend to be more frequently employed in university

counseling centers compared to hospitals and private practice for

clinical psychologists.

However, counseling and clinical psychologists can be employed in a

variety of settings, with a large degree of overlap (prisons, colleges,

community mental health, non-profits, corporations, private practice,

hospitals and Veterans Affairs). Distinctions between the two fields

continue to fade.

| Comparison of mental health professionals in USA

|

| Occupation

|

Degree

|

Common Licenses

|

Prescription Privilege

|

Ave. 2004

Income (USD)

|

| Clinical Psychologist

|

PhD/PsyD

|

Psychologist

|

Mostly no

|

$75,000

|

| Counseling Psychologist (Doctorate)

|

PhD/PsyD

|

Psychologist

|

No

|

$65,000

|

| Counseling Psychologist (Master's)

|

MA/MS/MC

|

MFT/LPC/LPA

|

No

|

$49,000

|

| School Psychologist

|

PhD, EdD

|

Psychologist

|

No

|

$78,000

|

| Psychiatrist

|

MD/DO

|

Psychiatrist

|

Yes

|

$145,600

|

| Clinical Social Worker

|

PhD/MSW

|

LCSW

|

No

|

$36,170

|

| Psychiatric Nurse

|

PhD/MSN/BSN

|

APRN/PMHN

|

No

|

$53,450

|

| Psychiatric and mental health Nurse Practitioner

|

DNP/MSN

|

MHNP

|

Yes (Varies by state)

|

$75,711

|

| Expressive/Art Therapist

|

MA

|

ATR

|

No

|

$45,000

|

School psychology

School psychologists

are primarily concerned with the academic, social, and emotional

well-being of children and adolescents within a scholastic environment.

In the U.K., they are known as "educational psychologists". Like

clinical (and counseling) psychologists, school psychologists with

doctoral degrees are eligible for licensure as health service

psychologists, and many work in private practice. Unlike clinical

psychologists, they receive much more training in education, child

development and behavior, and the psychology of learning. Common degrees

include the

Educational Specialist Degree (Ed.S.),

Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and

Doctor of Education (Ed.D.).

Traditional job roles for school psychologists employed in school

settings have focused mainly on assessment of students to determine

their eligibility for special education services in schools, and on

consultation with teachers and other school professionals to design and

carry out interventions on behalf of students. Other major roles also

include offering individual and group therapy with children and their

families, designing prevention programs (e.g. for reducing dropout),

evaluating school programs, and working with teachers and administrators

to help maximize teaching efficacy, both in the classroom and

systemically.

Clinical social work

Social workers

provide a variety of services, generally concerned with social

problems, their causes, and their solutions. With specific training,

clinical social workers may also provide psychological counseling (in

the U.S. and Canada), in addition to more traditional social work. The

Masters in Social Work in the U.S. is a two-year, sixty credit program

that includes at least a one-year practicum (two years for clinicians).

Occupational therapy

Occupational therapy—often

abbreviated OT—is the "use of productive or creative activity in the

treatment or rehabilitation of physically, cognitively, or emotionally

disabled people."

Most commonly, occupational therapists work with people with

disabilities to enable them to maximize their skills and abilities.

Occupational therapy practitioners are skilled professionals whose

education includes the study of human growth and development with

specific emphasis on the physical, emotional, psychological,

sociocultural,

cognitive

and environmental components of illness and injury. They commonly work

alongside clinical psychologists in settings such as inpatient and

outpatient mental health, pain management clinics, eating disorder

clinics, and child development services. OT's use support groups,

individual counseling sessions, and activity-based approaches to address

psychiatric symptoms and maximize functioning in life activities.

Criticisms and controversies

Clinical

psychology is a diverse field and there have been recurring tensions

over the degree to which clinical practice should be limited to

treatments supported by empirical research. Despite some evidence showing that all the major therapeutic orientations are about of equal effectiveness, there remains much debate about the efficacy of various forms treatment in use in clinical psychology.

It has been reported that clinical psychology has rarely allied itself with

client groups

and tends to individualize problems to the neglect of wider economic,

political and social inequality issues that may not be the

responsibility of the client.

It has been argued that therapeutic practices are inevitably bound up

with power inequalities, which can be used for good and bad. A

critical psychology

movement has argued that clinical psychology, and other professions

making up a "psy complex", often fail to consider or address

inequalities and power differences and can play a part in the social and

moral control of disadvantage, deviance and unrest.

An October 2009 editorial in the journal

Nature

suggests that a large number of clinical psychology practitioners in

the United States consider scientific evidence to be "less important

than their personal – that is, subjective – clinical experience."