Yanomami woman and her child, June 1997

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approximately 35,339 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 16,000 (2009) | |

| 19,338 (2011) | |

| Languages | |

| Yanomaman languages | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism | |

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

The name Yanomami

The ethnonym Yanomami was produced by anthropologists on the basis of the word yanõmami, which, in the expression yanõmami thëpë, signifies "human beings." This expression is opposed to the categories yaro (game animals) and yai (invisible or nameless beings), but also napë (enemy, stranger, non-Indian).

According to ethnologist Jacques Lizot:

Yanomami is the Indians' self-denomination...the term refers to communities disseminated to the south of the Orinoco, [whereas] the variant Yanomawi is used to refer to communities north of the Orinoco. The term Sanumá corresponds to a dialect reserved for a cultural subgroup, much influenced by the neighboring Ye'kuana people. Other denominations applied to the Yanomami include Waika or Waica, Guiaca, Shiriana, Shirishana, Guaharibo or Guajaribo, Yanoama, Ninam, and Xamatari or Shamatari.

History

The

first report of the Yanomami to the Western world is from 1759, when a

Spanish expedition under Apolinar Diez de la Fuente visited some Ye'kuana people living on the Padamo River. Diez wrote:

By interlocution of an Uramanavi Indian, I asked Chief Yoni if he had navigated by the Orinoco to its headwaters; he replied yes, and that he had gone to make war against the Guaharibo [Yanomami] Indians, who were not very brave...and who will not be friends with any kind of Indian.

From approximately 1630 to 1720, the other river-based indigenous

societies who lived in the same region were wiped out or reduced as a

result of slave-hunting expeditions by the conquistadors and bandeirantes.

How this affected the Yanomami is unknown. Sustained contact with the

outside world began in the 1950s with the arrival of members of the New Tribes Mission as well as Catholic missionaries from the Society of Jesus and Salesians of Don Bosco.

In Roraima,

the 1970s saw the implementation of development projects within the

framework of the "National Integration Plan" launched by the Brazilian

military governments of the time. This meant the opening of a stretch of

perimeter road (1973–76) and various colonization programs on land

traditionally occupied by the Yanomami. During the same period, the

Amazonian resources survey project RADAM (1975) detected important

mineral deposits in the region. This triggered a progressive movement of

gold prospectors, which after 1987 took the form of a real gold rush. Hundreds of clandestine runways were opened by gold miners in the major tributaries of the Branco River

between 1987 and 1990. The number of gold miners in the Yanomami area

of Roraima was then estimated at 30 to 40 thousand, about five times the

indigenous population resident there. Although the intensity of this

gold rush has subsided greatly since 1990, gold prospecting continues

today in the Yanomami land, spreading violence and serious health and

social problems.

Increasing pressure from farmers, cattle ranchers, and gold miners, as well as those interested in securing the Brazilian border

by constructing roads and military bases near Yanomami communities, led

to a campaign to defend the rights of the Yanomami to live in a

protected area. In 1978 the Pro-Yanomami Commission (CCPY) was

established. Originally named the Commission for the Creation of a

Yanomami Park, it is a Brazilian non-governmental nonprofit organization dedicated to the defense of the territorial, cultural, and civil and political rights

of the Yanomami. CCPY devoted itself to a long national and

international campaign to inform and sensitize public opinion and put

pressure on the Brazilian government to demarcate an area suited to the

needs of the Yanomami. After 13 years the Yanomami indigenous land was

officially demarcated in 1991 and approved and registered in 1992, thus

ensuring that indigenous people had the constitutional right to the

exclusive use of almost 96,650 square kilometres (37,320 sq mi) located

in the States of Roraima and Amazonas.

The Alto Orinoco-Casiquiare Biosphere Reserve was created in 1993 with the objective of preserving the traditional territory and lifestyle of the Yanomami and Ye'kuana peoples.

However, while the constitution of Venezuela recognizes indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral domains,

few have received official title to their territories and the

government has announced it will open up large parts of the Amazon

rainforest to legal mining.

Organization

The

Yanomami do not recognize themselves as a united group, but rather as

individuals associated with their politically autonomous villages.

Yanomami communities are grouped together because they have similar ages

and kinship, and militaristic coalitions interweave communities

together. The Yanomami have common historical ties to Carib speakers who resided near the Orinoco river and moved to the highlands of Brazil and Venezuela, the location the Yanomami currently occupy.

Mature men hold most political and religious authority. A tuxawa

(headman) acts as the leader of each village, but no single leader

presides over the whole of those classified as Yanomami. Headmen gain

political power by demonstrating skill in settling disputes both within

the village and with neighbouring communities. A consensus of mature

males is usually required for action that involves the community, but

individuals are not required to take part.

Domestic life and diet

Yanomami shabono

Groups of Yanomami live in villages usually consisting of their

children and extended families. Villages vary in size, but usually

contain between 50 and 400 native people. In this largely communal

system, the entire village lives under a common roof called the shabono. Shabonos have a characteristic oval shape, with open grounds in the centre measuring an average of 100 yards (91 m). The shabono shelter constitutes the perimeter of the village, if it has not been fortified with palisades.

Under the roof, divisions exist marked only by support posts, partitioning individual houses and spaces. Shabonos

are built from raw materials from the surrounding rainforest, such as

leaves, vines, and tree trunks. They are susceptible to heavy damage

from rains, winds, and insect infestation. As a result, new shabonos are constructed every 4 to 6 years.

The Yanomami can be classified as foraging horticulturalists, depending heavily on rainforest resources; they use slash-and-burn horticulture, grow bananas,

gather fruit, and hunt animals and fish. When the soil becomes

exhausted, Yanomami frequently move to avoid areas that have become

overused, a practice known as shifting cultivation.

Yanomami women in Venezuela

Children stay close to their mothers when young; most of the

childrearing is done by women. Yanomami groups are a famous example of

the approximately fifty documented societies that openly accept polyandry, though polygyny among Amazonian tribes has also been observed.

Many unions are monogamous. Polygamous families consist of a large

patrifocal family unit based on one man, and smaller matrifocal

subfamilies: each woman's family unit, composed of the woman and her

children. Life in the village is centered around the small, matrilocal

family unit, whereas the larger patrilocal unit has more political

importance beyond the village.

The Yanomami are known as hunters, fishers, and horticulturists. The women cultivate cooking plantains and cassava

in gardens as their main crops. Men do the heavy work of clearing areas

of forest for the gardens. Another food source for the Yanomami is grubs.

Often the Yanomami will cut down palms in order to facilitate the

growth of grubs. The traditional Yanomami diet is very low in edible

salt. Their blood pressure is characteristically among the lowest of any demographic group. For this reason, the Yanomami have been the subject of studies seeking to link hypertension to sodium consumption.

Location of the Yanomami peoples

Rituals

are a very important part of Yanomami culture. The Yanomami celebrate a

good harvest with a big feast to which nearby villages are invited. The

Yanomami village members gather large amounts of food, which helps to

maintain good relations with their neighbours. They also decorate their

bodies with feathers and flowers. During the feast, the Yanomami eat a

lot, and the women dance and sing late into the night.

Hallucinogens or entheogens, known as yakoana or ebene, are used by Yanomami shamans as part of healing rituals for members of the community who are ill. Yakoana also refers to the tree from which it is derived, Virola elongata. Yopo, derived from a different plant with hallucinogenic effects (Anadenanthera peregrina), is usually cultivated in the garden by the shaman. The Xamatari also mix the powdered bark of Virola elongata with the powdered seeds of yopo to create the drug ebene. The drugs facilitate communication with the hekura, spirits that are believed to govern many aspects of the physical world. Women do not engage in this practice, known as shapuri.

The Yanomami people practice ritual endocannibalism, in which they consume the bones of deceased kinsmen. The body is wrapped in leaves and placed in the forest some distance from the shabono; then after insects have consumed the soft tissue (usually about 30 to 45 days), the bones are collected and cremated.

The ashes are then mixed with a kind of soup made from bananas, which

is consumed by the entire community. The ashes may be preserved in a gourd

and the ritual repeated annually until the ashes are gone. In daily

conversation, no reference may be made to a dead person except on the

annual "day of remembrance", when the ashes of the dead are consumed and

people recall the lives of their deceased relatives. This tradition is

meant to strengthen the Yanomami people and keep the spirit of that

individual alive.

The women are responsible for many domestic duties and chores, excluding hunting and killing game for food. Although the women do not hunt, they do work in the gardens and gather fruits, tubers, nuts and other wild foodstuffs. The garden plots are sectioned off by family, and grow bananas, plantains, sugarcane, mangoes, sweet potatoes, papayas, cassava, maize, and other crops.

Yanomami women cultivate until the gardens are no longer fertile, and

then move their plots. Women are expected to carry 70 to 80 pounds (32

to 36 kg) of crops on their backs during harvesting, using bark straps

and woven baskets.

In the mornings, while the men are off hunting, the women and young children go off in search of termite nests and other grubs, which will later be roasted at the family hearths. The women also pursue frogs, terrestrial crabs, or caterpillars,

or even look for vines that can be woven into baskets. While some women

gather these small sources of food, other women go off and fish for

several hours during the day. The women also prepare cassava, shredding the roots and expressing the toxic juice, then roasting the flour to make flat cakes (known in Spanish as casabe), which they cook over a small pile of coals.

Yanomami women

are expected to take responsibility for the children, who are expected

to help their mothers with domestic chores from a very young age, and

mothers rely very much on help from their daughters. Boys typically

become the responsibility of the male members of the community after

about age 8.

Using small strings of bark and roots, Yanomami women weave and decorate baskets. They use these baskets to carry plants, crops, and food to bring back to the shabono. They use a red berry known as onoto or urucu to dye the baskets, as well as to paint their bodies and dye their loin cloths. After the baskets are painted, they are further decorated with masticated charcoal pigment.

Female puberty and menstruation

The start of menstruation symbolizes the beginning of womanhood. Girls typically start menstruation around the age of 12-15.

Girls are often betrothed before menarche and the marriage may only be

consummated once the girl starts menstruating, though the taboo is often

violated and many girls become sexually active before then. The Yanomami word for menstruation (roo)

translates literally as "squatting" in English, as they use no pads or

cloths to absorb the blood. Due to the belief that menstrual blood is poisonous

and dangerous, girls are kept hidden away in a small tent-like

structure constructed of a screen of leaves. A deep hole is built in the

structure over which girls squat, to "rid themselves" of their blood.

These structures are regarded as isolation screens.

Yanomami girl at Xidea, Brazil, August 1997.

The mother

is notified immediately, and she, along with the elder female friends

of the girl, are responsible for disposing of her old cotton garments and must replace them with new ones symbolizing her womanhood and availability for marriage.

During the week of that first menstrual period the girl is fed with a

stick, for she is forbidden from touching the food in any way. While on

confinement she has to whisper when speaking and she may speak only to

close kin, such as sisters or her mother, but never a male.

Up until the time of menstruation, girls are treated as children,

and are only responsible for assisting their mothers in household work.

When they approach the age of menstruation, they are sought out by

males as potential wives. Puberty

is not seen as a significant time period with male Yanomami children,

but it is considered very important for females. After menstruating for

the first time, the girls are expected to leave childhood and enter

adulthood, and take on the responsibilities of a grown Yanomami woman.

After a young girl gets her period, she is forbidden from showing her genitalia and must keep herself covered with a loincloth.

The menstrual cycle

of Yanomami women does not occur frequently due to constant nursing or

child birthing, and is treated as a very significant occurrence only at

this time.

Language

Yanomaman languages comprise four main varieties: Ninam, Sanumá, Waiká, and Yanomamö.

Many local variations and dialects also exist, such that people from

different villages cannot always understand each other. Many linguists

consider the Yanomaman family to be a language isolate, unrelated to other South American indigenous languages. The origins of the language are obscure.

Violence

Traditional face painting.

In

early anthropological studies the Yanomami culture was described as

being permeated with violence. The Yanomami people have a history of

acting violently not only towards other tribes, but towards one another.

An influential ethnography by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon described the Yanomami as living in "a state of chronic warfare".

Chagnon's account and similar descriptions of the Yanomami portrayed

them as aggressive and warlike, sparking controversy amongst

anthropologists and creating an enormous interest in the Yanomami. The

debate centered around the degree of violence in Yanomami society, and

the question of whether violence and warfare were best explained as an

inherent part of Yanomami culture, or rather as a response to specific

historical situations. Writing in 1985, anthropologist Jacques Lizot, who had lived among the Yanomami for more than twenty years, stated:

I would like my book to help revise the exaggerated representation that has been given of Yanomami violence. The Yanomami are warriors; they can be brutal and cruel, but they can also be delicate, sensitive, and loving. Violence is only sporadic; it never dominates social life for any length of time, and long peaceful moments can separate two explosions. When one is acquainted with the societies of the North American plains or the societies of the Chaco in South America, one cannot say that Yanomami culture is organized around warfare as Chagnon does.

Anthropologists working in the ecologist tradition, such as Marvin Harris,

argued that a culture of violence had evolved among the Yanomami

through competition resulting from a lack of nutritional resources in

their territory. However, the 1995 study "Yanomami Warfare", by R. Brian Ferguson, examined all documented cases of warfare among the Yanomami and concluded:

Although some Yanomami really have been engaged in intensive warfare and other kinds of bloody conflict, this violence is not an expression of Yanomami culture itself. It is, rather, a product of specific historical situations: The Yanomami make war not because Western culture is absent, but because it is present, and present in certain specific forms. All Yanomami warfare that we know about occurs within what Neil Whitehead and I call a "tribal zone", an extensive area beyond state administrative control, inhabited by nonstate people who must react to the far-flung effects of the state presence.

Ferguson stresses the idea that contrary to Chagnon's description of

the Yanomami as unaffected by Western culture, the Yanomami experienced

the effects of colonization long before their territory became

accessible to Westerners in the 1950s, and that they had acquired many

influences and materials from Western culture through trade networks

much earlier.

Lawrence Keeley questioned Ferguson's analysis, writing that the

character and speed of changes caused by contact with civilization are

not well understood, and that diseases, trade items, weapons, and

population movements likely all existed as possible contributors to

warfare before civilization.

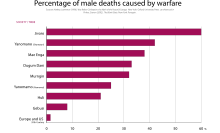

Percentage of male deaths due to warfare in two Yanomami subgroups, as compared to other indigenous ethnic groups in New Guinea and South America and to some industrialized nations.

Violence is one of the leading causes of Yanomami death. Up to half

of all of Yanomami males die violent deaths in the constant conflict

between neighboring communities over local resources. Often these

confrontations lead to Yanomami leaving their villages in search of new

ones.

Women are often victims of physical abuse and anger. Inter-village

warfare is common, but does not too commonly affect women. When Yanomami

tribes fight and raid nearby tribes, women are often raped, beaten, and brought back to the shabono

to be adopted into the captor's community. Wives may be beaten

frequently, so as to keep them docile and faithful to their husbands. Sexual jealousy causes much of the violence. Women are beaten with clubs, sticks, machetes, and other blunt or sharp objects. Burning with a branding stick occurs often, and symbolizes a male’s strength or dominance over his wife.

Yanomami men have been known to kill children while raiding enemy villages. Helena Valero, a Brazilian woman kidnapped by Yanomami warriors in the 1930s, witnessed a Karawetari raid on her tribe:

They killed so many. I was weeping for fear and for pity but there was nothing I could do. They snatched the children from their mothers to kill them, while the others held the mothers tightly by the arms and wrists as they stood up in a line. All the women wept... The men began to kill the children; little ones, bigger ones, they killed many of them.

Controversies

Gold was found in Yanomami territory in the early 1970s and the inevitable influx of miners brought disease, alcoholism, and violence. Yanomami culture was severely endangered.

In the mid-1970s, garimpeiros (small independent gold-diggers) started to enter the Yanomami country. Where these garimpeiros settled, they killed members of the Yanomami tribe in conflict over land. In addition, mining techniques by the garimpeiros led to environmental degradation. Despite the existence of FUNAI,

the federal agency representing the rights and interests of indigenous

populations, the Yanomami have received little protection from the

government against these intrusive forces. In some cases the government

can be cited as supporting the infiltration of mining companies into

Yanomami lands. In 1978, the militarized government, under pressure from

anthropologists and the international community, enacted a plan that

demarcated land for the Yanomami. These reserves, however, were small

"island" tracts of land lacking consideration for Yanomami lifestyle,

trading networks, and trails, with boundaries that were determined

solely by the concentration of mineral deposits. In 1990, more than 40,000 garimpeiros had entered the Yanomami land. In 1992, the government of Brazil, led by Fernando Collor de Mello, demarcated an indigenous Yanomami area on the recommendations of Brazilian anthropologists and Survival International,

a campaign that started in the early 1970s. Non-Yanomami people

continue to enter the land; the Brazilian and Venezuelan governments do

not have adequate enforcement programs to prevent the entry of

outsiders.

Ethical controversy has arisen about Yanomami blood taken for study by scientists such as Napoleon Chagnon and his associate James Neel.

Although Yanomami religious tradition prohibits the keeping of any

bodily matter after the death of that person, the donors were not warned

that blood samples would be kept indefinitely for experimentation.

Several prominent Yanomami delegations have sent letters to the

scientists who are studying them, demanding the return of their blood

samples. These samples are currently being taken out of storage for

shipping to the Amazon as soon as the scientists can figure out whom to

deliver them to and how to prevent any potential health risks in doing

so.

Members of the American Anthropological Association debated a dispute that has divided their discipline, voting 846 to 338 to rescind a 2002 report on allegations of misconduct by scholars studying the Yanomami people. The dispute has raged since Patrick Tierney published Darkness in El Dorado

in 2000. The book charged that anthropologists had repeatedly caused

harm—and in some cases, death—to members of the Yanomami people whom

they had studied in the 1960s. In 2010, Brazilian director José Padilha revisited the Darkness in El Dorado controversy in his documentary Secrets of the Tribe.

Population decrease

From 1987 to 1990, the Yanomami population was severely affected by malaria, mercury poisoning, malnutrition, and violence due to an influx of garimpeiros searching for gold in their territory.

Without the protection of the government, Yanomami populations declined

when miners were allowed to enter the Yanomami territory frequently

throughout this 3-year span. In 1987, FUNAI President Romero Jucá denied that the sharp increase in Yanomami deaths was due to garimpeiro invasions, and José Sarney, then president of Brazil, also supported the economic venture of the garimpeiros over the land rights of the Yanomami.

Alcida Rita Ramos, an anthropologist who worked closely with the

Yanomami, says this three-year period "led to charges against Brazil for

genocide."

Massacres

The Haximu massacre, also known as the Yanomami massacre, was an armed conflict in 1993, just outside Haximu, Brazil, close to the border with Venezuela. A group of garimpeiros killed approximately 16 Yanomami. In turn, Yanomami warriors killed at least two garimpeiros and wounded two more.

In July 2012 the government of Venezuela investigated another

alleged massacre. According to the Yanomami, a village of eighty people

was attacked by a helicopter and the only known survivors of the village

were three men who happened to be out hunting while the attack

occurred. However, in September 2012 Survival International,

who had been supporting the Yanomami in this allegation, retracted

their support after journalists could find no evidence to support the

claim.

Groups working for the Yanomami

David Good, son of the anthropologist Kenneth Good and his wife Yarima, created The Good Project to help support the future of the Yanomami people.

UK-based non-governmental organization Survival International has created global awareness-raising campaigns on the human rights situation of the Yanomami people.

In 1988 the US-based World Wildlife Fund (WWF) funded the musical Yanomamo, by Peter Rose and Anne Conlon, to convey what is happening to the people and their natural environment in the Amazon rainforest. It tells of Yanomami tribesmen/tribeswomen living in the Amazon and has been performed by many drama groups around the world.

The German-based non-governmental organization Yanomami-Hilfe eV

is building medical stations and schools for the Yanomami in Venezuela

and Brazil. Founder Christina Haverkamp

crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1992 on a self-made bamboo raft in order

to draw attention to the continuing oppression of the Yanomami people.

The Brazilian-based Yanomami formed their own indigenous organization Hutukara Associação Yanomami and accompanying website.

Comissão Pró-Yanomami (CCPY)

CCPY (formerly Comissão pela Criação do Parque Yanomami) is a Brazilian NGO focused on improving health care and education for the Yanomami. Established in 1978 by photographer Claudia Andujar,

anthropologist Bruce Albert, and Catholic missionary Carlo Zacquini,

CCPY has dedicated itself to the defense of Yanomami territorial rights

and the preservation of Yanomami culture. CCPY launched an international

campaign to publicize the destructive effects of the garimpeiro

invasion and promoted a political movement to designate an area along

the Brazil-Venezuela border as the Yanomami Indigenous Area. This campaign was ultimately successful.

Following demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Area in 1992,

CCPY's health programs, in conjunction with the now-defunct NGO URIHI

(Yanomami for "forest"), succeeded in reducing the incidence of malaria

among the Brazilian Yanomami by educating Yanomami community health agents

in how to diagnose and treat malaria. Between 1998 and 2001 the

incidence of malaria among Brazilian Yanomami Indians dropped by 45%.

In 2000, CCPY sponsored a project to foster a market for

Yanomami-grown fruit trees. This project aimed to help the Yanomami as

they transition to an increasingly sedentary lifestyle because of

environmental and political pressures.

In a separate venture, the CCPY, per the request of Yanomami leaders,

established Yanomami schools that teach Portuguese, aiming to aid the

Yanomami in their navigation of Brazilian politics and international

arenas in their struggle to defend land rights. Additionally, these

village schools teach Yanomami about Brazilian society, including money

use, good production, and record-keeping.

In popular culture

- The Yanomami's reputation for violence was dramatized in Ruggero Deodato's controversial film Cannibal Holocaust, in which natives apparently practiced endocannibalism.

- Peter Rose and Anne Conlon, Yanomamo, a musical entertainment published by Josef Weinberger, London (1983)

- The 2008 Christian movie Yai Wanonabälewä: The Enemy God featured one of the Yanomami in the telling of the history and culture of his people.

- In the 2006 novel World War Z by Max Brooks, a Brazilian doctor named Fernando Oliveira, in the aftermath of the titular zombie war, is living with the Yanomami. It is unclear whether he is being kept as a hostage or taking refuge.

- In the animated series Metalocalypse (season 2, episode 9), a Yanomami tribe is shown, and they share with the main characters their drug made of yopo.

- The Yanomami are mentioned as kinfolk to jaguar werecats known as "Balam", in the Tabletop role-playing game, Werewolf: The Apocalypse.

- In the Sergio Bonelli comic book Mister No, the eponymous protagonist was once married to a Yanomami woman and often interacts with Yanomami (they are called "Yanoama" in the comic).