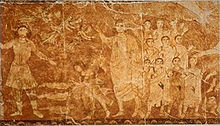

Samuel anoints David, Dura Europos, Syria, Date: 3rd century CE.

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, romanized: māšîaḥ; Greek: μεσσίας, romanized: messías, Arabic: مسيح, romanized: masîḥ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people.

The concepts of moshiach, messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible; a moshiach (messiah) is a king or High Priest traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil. Messiahs were not exclusively Jewish: the Book of Isaiah refers to Cyrus the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire, as a messiah for his decree to rebuild the Jerusalem Temple.

Ha mashiach (המשיח, 'the Messiah', 'the anointed one'), often referred to as melekh mashiach (מלך המשיח 'King Messiah'), is to be a human leader, physically descended from the paternal Davidic line through King David and King Solomon. He is thought to accomplish predetermined things in only one future arrival, including the unification of the tribes of Israel, the gathering of all Jews to Eretz Israel, the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, the ushering in of a Messianic Age of global universal peace, and the annunciation of the world to come.

In Christianity, the Messiah is called the Christ, from Greek: χριστός, romanized: khristós, translating the Hebrew word of the same meaning.

The concept of the Messiah in Christianity originated from the Messiah

in Judaism. However, unlike the concept of the Messiah in Judaism, the

Messiah in Christianity is the Son of God. Christ became the accepted Christian designation and title of Jesus of Nazareth, because Christians believe that the messianic prophecies in the Old Testament were fulfilled in his mission, death, and resurrection. These specifically include the prophecies of him being descended from the Davidic line, and being declared King of the Jews which happened on the day of his crucifixion.

They believe that Christ will fulfill the rest of the messianic

prophecies, specifically that he will usher in a Messianic Age and the world to come at his Second Coming.

In Islam, Jesus was a prophet and the Masîḥ (مسيح), the Messiah sent to the Israelites, and he will return to Earth at the end of times, along with the Mahdi, and defeat al-Masih ad-Dajjal, the false Messiah.

In Ahmadiyya theology, these prophecies concerning the Mahdi and the second coming of Jesus have been fulfilled in Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908), the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, and the terms 'Messiah' and 'Mahdi' are synonyms for one and the same person.

In Chabad messianism, Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (r. 1920–1950), sixth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of Chabad Lubavitch, and Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), seventh Rebbe of Chabad, are Messiah claimants.

Resembling early Christianity, the deceased Schneerson is believed to

be the Messiah among some adherents of the Chabad movement; his second

coming is believed to be imminent.

Etymology

Messiah (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, Modern: Mashiaẖ, Tiberian: Māšîăḥ; in modern Jewish texts in English spelled Mashiach; Aramaic: משיחא, Greek: Μεσσίας, Classical Syriac: ܡܫܺܝܚܳܐ, Məšîḥā, Arabic: المسيح, al-Masīḥ, Latin: Messias) literally means "anointed one". In Hebrew, the Messiah is often referred to as מלך המשיח (Meleḵ ha-Mašīaḥ in the Tiberian vocalization, pronounced [ˈmeleχ hamaˈʃiaħ], literally meaning "the Anointed King".)

The Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament renders all thirty-nine instances of the Hebrew word for "anointed" (Mašíaḥ) as Χριστός (Khristós). The New Testament records the Greek transliteration Μεσσίας, Messias twice in John.

al-Masīḥ (proper name, pronounced [maˈsiːħ]) is the Arabic word for messiah. In modern Arabic, it is used as one of the many titles of Jesus. Masīḥ is used by Arab Christians as well as Muslims, and is written as Yasūʿ al-Masih (يسوع المسيح) by Arab Christians or ʿĪsā al-Masīḥ (عيسى المسيح) by Muslims. The word al-Masīḥ literally means "the anointed", "the traveller", or the "one who cures by caressing".

Judaism

The literal translation of the Hebrew word mashiach (messiah) is "anointed", which refers to a ritual of consecrating someone or something by putting holy oil upon it. It is used throughout the Hebrew Bible

in reference to a wide variety of individuals and objects; for example,

kings, priests and prophets, the altar in the Temple, vessels,

unleavened bread, and even a non-Jewish king (Cyrus the Great).

In Jewish eschatology, the term came to refer to a future Jewish king from the Davidic line, who will be "anointed" with holy anointing oil, to be king of God's kingdom, and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age. In Judaism, the Messiah is not considered to be God or a pre-existent divine Son of God. He is considered to be a great political leader that has descended from King David. That is why he is referred to as Messiah ben David,

which means "Messiah, son of David". The messiah, in Judaism, is

considered to be a great, charismatic leader that is well oriented with

the laws that are followed in Judaism. He will be the one who will not "judge by what his eyes see" or "decide by what his ears hear".

Belief in the eventual coming of a future messiah is a fundamental part of Judaism, and is one of Maimonides' 13 Principles of Faith.

Maimonides describes the identity of the Messiah in the following terms:

And if a king shall arise from among the House of David, studying Torah and occupied with commandments like his father David, according to the written and oral Torah, and he will impel all of Israel to follow it and to strengthen breaches in its observance, and will fight God's wars, this one is to be treated as if he were the anointed one. If he succeeded and built the Holy Temple in its proper place and gathered the dispersed ones of Israel together, this is indeed the anointed one for certain, and he will mend the entire world to worship the Lord together, as it is stated: "For then I shall turn for the nations a clear tongue, so that they will all proclaim the Name of the Lord, and to worship Him with a united resolve (Zephaniah 3:9)."

Even though the eventual coming of the messiah is a strongly upheld

belief in Judaism, trying to predict the actual time when the messiah

will come is an act that is frowned upon. These kinds of actions are

thought to weaken the faith the people have in the religion. So in

Judaism, there is no specific time when the messiah comes. Rather, it is

the acts of the people that determines when the messiah comes. It is

said that the messiah would come either when the world needs his coming

the most (when the world is so sinful and in desperate need of saving by

the messiah) or deserves it the most (when genuine goodness prevails in

the world).

A common modern rabbinic interpretation is that there is a potential messiah in every generation. The Talmud, which often uses stories to make a moral point (aggadah), tells of a highly respected rabbi who found the Messiah at the gates of Rome

and asked him, "When will you finally come?" He was quite surprised

when he was told, "Today." Overjoyed and full of anticipation, the man

waited all day. The next day he returned, disappointed and puzzled, and

asked, "You said messiah would come 'today' but he didn't come! What

happened?" The Messiah replied, "Scripture says, 'Today, if you will but

hearken to his voice.'"

A Kabbalistic

tradition within Judaism is that the commonly discussed messiah who

will usher in a period of freedom and peace, Messiah ben David, will be

preceded by Messiah ben Joseph,

who will gather the children of Israel around him, lead them to

Jerusalem. After overcoming the hostile powers in Jerusalem, Messiah ben

Joseph, will reestablish the Temple-worship and set up his own

dominion. Then Armilus, according to one group of sources, or Gog and Magog,

according to the other, will appear with their hosts before Jerusalem,

wage war against Messiah ben Joseph, and slay him. His corpse, according

to one group, will lie unburied in the streets of Jerusalem; according

to the other, it will be hidden by the angels with the bodies of the

Patriarchs, until Messiah ben David comes and brings him back to life.

Chabad

Chabad

Halachic ruling declaring "every single Jew" had to believe in the

imminent second coming of the deceased 7th Lubavitcher Rebbe as the

Messiah

Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (r. 1920 - 1950), sixth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of Chabad Lubavitch, and Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902 - 1994), seventh Rebbe of Chabad, are messiah claimants.

As per Chabad-Lubavitch messianism, Menachem Mendel Schneerson openly declared his deceased father-in-law, the former 6th Rebbe of Chabad Lubavitch, to be the Messiah. He published about Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn to be "Atzmus u'mehus alein vi er hat zich areingeshtalt in a guf" (Yiddish and English for: "Essence and Existence [of God] which has placed itself in a body"). The gravesite of his deceased father-in-law Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, known as "the Ohel", became a central point of focus for Menachem Mendel Schneerson's prayers and supplications.

Regarding the deceased Menachem Mendel Schneerson, a later Chabad

Halachic ruling claims that it was "incumbent on every single Jew to

heed the Rebbe's words and believe that he is indeed King Moshiach, who will be revealed imminently". Outside of Chabad messianism, in Judaism, there is no basis to these claims. If anything, this resembles the faith in the resurrection of Jesus and his second coming in early Christianity.

Still today, the deceased rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson is believed to be the Messiah among adherents of the Chabad movement, and his second coming is believed to be imminent. He is venerated and invocated to by thousands of visitors and letters each year at two bamot-tombs (Ohel), especially in a pilgrimage each year on the anniversary of his death.

Christianity

The Last Judgment, by Jean Cousin the Younger (c. late 16th century)

The Greek translation of Messiah is khristos (χριστός), anglicized as Christ,

and Christians commonly refer to Jesus as either the "Christ" or the

"Messiah". Christians believe that messianic prophecies were fulfilled

in the mission, death, and resurrection of Jesus and that he will return to fulfill the rest of messianic prophecies.

The majority of historical and mainline Christian theologies consider Jesus to be the Son of God and God the Son, a concept of the Messiah fundamentally different from the Jewish and Islamic concepts. In each of the four New Testament Gospels, the only literal anointing of Jesus

is conducted by a woman. In the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and John,

this anointing occurs in Bethany, outside Jerusalem. In the Gospel of

Luke, the anointing scene takes place at an indeterminate location, but

context suggests it to be in Galilee, or even a separate anointing

altogether.

Islam

While the term "messiah" does appear in Islam, the meaning is

different from that found in Christianity and Judaism. "Though Islam

shares many of the beliefs and characteristics of the two

Semitic/Abrahamic/monotheistic religions which preceded it, the idea of

messianism, which is of central importance in Judaism and Christianity,

is alien to Islam as represented by the Qur'an."

The Quran identifies Jesus (Isa) as the messiah (Masih),

who will one day return to earth. At the time of the second coming,

"according to Islamic tradition, Jesus will come again and exercise his

power of healing. He will forever destroy falsehood, as embodied in the

Daj-jal, the great falsifier, the anti-Christ. Then God will reign forever."

Jesus is one of the most important prophets in the Islamic tradition, along with Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Muhammad.

Unlike Christians, Muslims see Jesus as a prophet, but not as God

himself or the son of God. Like all other prophets, Jesus is an ordinary

man, who receives revelations from God. According to religious scholar Mona Siddiqui,

in Islam, "Prophecy allows God to remain veiled and there is no

suggestion in the Qur'an that God wishes to reveal of himself just yet.

Prophets guarantee interpretation of revelation and that God's message

will be understood."

Prophecy in human form does not represent the true powers of God,

contrary to the way Jesus is depicted in mainstream Christianity.

The Quran states that Isa, the Son of Maryam (Arabic: Isa ibn Maryam), is the messiah and prophet sent to the Children of Israel. The birth of Isa is described in Quran sura 19 verses 1–33, and sura 4 verse 171 explicitly states Isa as the Son of Maryam. Sunni Muslims

believe Isa is alive in Heaven and did not die in the crucifixion, as

depicted in mainstream Christianity. According to religious scholar Mahmoud Ayoub,

"Jesus' close proximity or nearness (qurb) to God is affirmed in the

Qur'anic insistence that Jesus did not die, but was taken up to God and

remains with God" The Quran in sura 4 verse 157-158 states that: "They did not kill him,

nor did they crucify him, but they thought they did" since the messiah

was "made to resemble him to them."

It is believed that Isa will return to Earth to defeat the Masih ad-Dajjal (false Messiah), a figure similar to the Antichrist in Christianity, who will emerge shortly before Yawm al-Qiyāmah ("the Day of Resurrection"). The Mahdi will come shortly before the second coming of Jesus. After he has destroyed ad-Dajjal, his final task will be to become leader of the Muslims. Isa will unify the Muslim Ummah

(the followers of Islam) under the common purpose of worshipping Allah

alone in pure Islam, thereby ending divisions and deviations by

adherents. Mainstream Muslims believe that at that time Isa will dispel

Christian and Jewish claims about him.

The Prophet said: There is no prophet between me and him, that is, Isa. He will descend (to the earth). When you see him, recognise him: a man of medium height, reddish fair, wearing two light yellow garments, looking as if drops were falling down from his head though it will not be wet. He will fight the people for the cause of Islam. He will break the cross, kill swine, and abolish jizyah. Allah will perish all religions except Islam. He will destroy the Antichrist and will live on the earth for forty years and then he will die. The Muslims will pray over him.

Both Sunni and Shia Muslims agree

that al-Mahdi will arrive first, and after him, Isa. Isa will proclaim

al-Mahdi as the Islamic community leader. A war will be fought—the

Dajjal against al-Mahdi and Isa. This war will mark the approach of the

coming of the Last Day. After Isa slays al-Dajjāl at the Gate of Lud, he will bear witness and reveal that Islam is indeed the true and last word from God to humanity as Yusuf Ali's

translation reads: "And there is none of the People of the Book but

must believe in him before his death; and on the Day of Judgment he will

be a witness against them." A hadith in Sahih Bukhari says:

"Allah's Apostle said 'How will you be when the son of Mariam descends among you and your Imam is from among you?'"

The Quran denies the crucifixion of Jesus, claiming that he was neither killed nor crucified. The Quran also emphasizes the difference between Allah (God in Arabic)

and the Messiah:

"Those who say that Allah is the Messiah, son of Mary, are unbelievers.

The Messiah said: "O Children of Israel, worship Allah, my Lord and your

Lord... unbelievers too are those who have said that Allah is the third

of three... the Messiah, son of Mary, was only a Messenger before whom

other Messengers had gone."

Shia Islam

Shi'i Islam, which significantly values and revolves around the 12 spiritual leaders called Imams,

differs significantly from the beliefs of Sunni Islam. Unlike Sunni

Islam, "Messianism is an essential part of religious belief and practice

for almost all Shi'a Muslims."

Shi'i Islam believes that the last Imam will return again, with the

return of Jesus. According to religious scholar Mona Sidique, "Shi'is

are acutely aware of the existence everywhere of the twelfth Imam, who

disappeared in 874. Shi'i piety teaches that the hidden Imam will return

with Jesus Christ to set up the messianic kingdom before the final

Judgement Day, when all humanity will stand before God. There is some

controversy as to the identity of this imam. There are sources that

underscore how the Shia sect agrees with the Jews and Christians that

Imam Mehdi (al-Mahdi) is another name for Elijah, whose return prior to

the arrival of the Messiah was prophesied in the Old Testament. On the other hand, there is also belief from among Shia and Sunni adherents that the imam will be Muhammad.

The Imams and Fatima will have a direct impact on the judgements

rendered that day. This will represent the ultimate intercession."

There is debate on whether Shi'i Muslims should accept the death of

Jesus. Religious scholar Mahmou Ayoub argues "Modern Shi'i thinkers have

allowed the possibility that Jesus died and only his spirit was taken

up to heaven." Conversely, religious scholar Mona Siddiqui argues that Shi'i thinkers believe Jesus was "neither crucified nor slain." She also argues that Shi'i Muslims believe that the twelfth imam did not die, but "was taken to God to return in God's time," and "will return at the end of history to establish the kingdom of God on earth as the expected Mahdi."

Other sects

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, considered by Ahmadis to be the Promised Messiah of the latter days

- In Ahmadiyya theology, the terms "Messiah" and "Mahdi" are synonymous terms for one and the same person. The term "Mahdi" means guided by God, thus implying a direct ordainment by God of a divinely chosen individual.

According to Ahmadiyya thought, Messiahship is a phenomenon through

which a special emphasis is given on the transformation of a people by

way of offering suffering for the sake of God instead of giving

suffering (i.e. refraining from revenge). Ahmadis believe that this special emphasis was given through the person of Jesus and Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908) among others.

Ahmadis hold that the prophesied eschatological figures of

Christianity and Islam, the Messiah and Mahdi, were in fact to be

fulfilled in one person who was to represent all previous prophets.

Numerous hadith are presented by the Ahmadis in support of their view, such as one from Sunan Ibn Majah, which says, "There is No Mahdi other than Jesus son of Mary."

Ahmadis believe that the prophecies concerning the Mahdi and the

second coming of Jesus have been fulfilled in Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

(1835–1908), the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement. Unlike mainstream

Muslims, the Ahmadis do not believe that Jesus is alive in heaven, but

that he survived the crucifixion and migrated towards the east where he

died a natural death and that Ghulam Ahmad was only the promised

spiritual second coming and likeness of Jesus, the promised Messiah and

Mahdi. He also claimed to have appeared in the likeness of Krishna and that his advent fulfilled certain prophecies found in Hindu scriptures. He stated that the founder of Sikhism was a Muslim saint, who was a reflection of the religious challenges he perceived to be occurring. Ghulam Ahmad wrote Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, in 1880, which incorporated Indian, Sufi, Islamic and Western aspects in order to give life to Islam in the face of the British Raj,

Protestant Christianity, and rising Hinduism. He later declared himself

the Promised Messiah and the Mahdi following Divine revelations in

1891. Ghulam Ahmad argued that Jesus had appeared 1300 years after the

formation of the Muslim community and stressed the need for a current

Messiah, in turn claiming that he himself embodied both the Mahdi and

the Messiah. Ghulam Ahmad was supported by Muslims who especially felt

oppressed by Christian and Hindu missionaries.

- In Buddhism, Maitreya is considered to the next Buddha (awakened one) that is promised to come. He is expected to come to renew the laws of Buddhism once the teaching of Gautama Buddha has completely decayed.

- Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Bahá'í Faith, claimed to be the figure prophesied in the scriptures of the world's religions. His name, when translated literally, means "The Glory of God" in Arabic. According to the Bahá'í Faith, Bahá'u'lláh addressed not only those timeless theological and philosophical questions that have stayed with humanity since old times such as: Who is God? What is goodness? and Why are we here? but also the questions that have preoccupied philosophers of the 20th century: What motivates human nature? Is real peace indeed possible? Does God still care for humanity? and the like. He taught that there is only one God, that all of the world's religions are from God, and that now is the time for humanity to recognize its oneness and unite.

- Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia is believed to be the Messiah by followers of the Rastafari movement. This idea further supports the belief that God himself is black, which they (followers of the Rastafarian movement) try to further strengthen by a verse from the Bible. Even if the Emperor denied being the messiah, the followers of the Rastafari movement believe that he is a messenger from God. To justify this, Rastafarians used reasons such as Emperor Haile Selassie's bloodline, which is assumed to come from King Solomon of Israel, and the various titles given to him, which include Lord of Lords, King of Kings and Conquering Lion of the tribe of Judah.

- In Kebatinan (Javanese religious tradition), Satrio Piningit is a character in Jayabaya's prophecies who is destined to become a great leader of Nusantara and to rule the world from Java. In Serat Pararaton, King Jayabaya of Kediri foretold that before Satrio Piningit's coming, there would be flash floods and that volcanoes would erupt without warning. Satrio Piningit is a Krishna-like figure known as "Ratu Adil" (Indonesian King of Justice) and his weapon is a trishula.

Popular culture

- The Messiah, a 2007 Persian film depicting the life of Jesus from an Islamic perspective

- The Young Messiah, a 2016 American film depicting the childhood life of Jesus from a Christian perspective

- Dune Messiah, a 1969 novel by Frank Herbert, second in his Dune trilogy, also part of a miniseries, one of the widest-selling works of fiction in the 1960s

- Messiah is the final persona of Persona 3's protagonist, obtained after he understands the meaning of his journey

The following works include the concept of a messiah as a leader of a cause or liberator of a people:

- The Jewish Messiah, a 2008 novel by Arnon Grunberg

- Messiah, a 1999 novel by Andrei Codrescu