| Andes Mountains | |

|---|---|

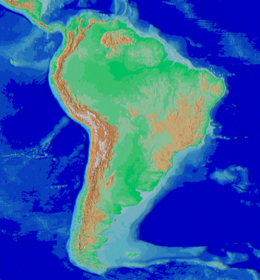

The

Andes mountain range as seen from a plane, between Santiago de Chile

and Mendoza, Argentina, in summer. The large icefield corresponds to the

southern slope of San José volcano (left) and Marmolejo (right). Tupungato at their right.

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Aconcagua (Las Heras Department, Mendoza, Argentina) |

| Elevation | 6,961 m (22,838 ft) |

| Coordinates | 32°S 70°WCoordinates: 32°S 70°W |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 7,000 km (4,300 mi) |

| Width | 50 km (31 mi) |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Anti (Quechua) |

| Geography | |

| Countries | |

The Andes or Andean Mountains (Spanish: Cordillera de los Andes) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The Andes also have the 2nd most elevated highest peak of any mountain range, only behind the Himalayas. The range is 7,000 km (4,300 mi) long, 200 to 700 km (120 to 430 mi) wide (widest between 18° south and 20° south latitude), and has an average height of about 4,000 m (13,000 ft). The Andes extend from north to south through seven South American countries: Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina.

Along their length, the Andes are split into several ranges, separated by intermediate depressions. The Andes are the location of several high plateaus – some of which host major cities such as Quito, Bogotá, Cali, Arequipa, Medellín, Bucaramanga, Sucre, Mérida and La Paz. The Altiplano plateau is the world's second-highest after the Tibetan plateau. These ranges are in turn grouped into three major divisions based on climate: the Tropical Andes, the Dry Andes, and the Wet Andes.

The Andes Mountains are the world's highest mountain range outside Asia. The highest mountain outside Asia, Argentina's Mount Aconcagua, rises to an elevation of about 6,961 m (22,838 ft) above sea level. The peak of Chimborazo in the Ecuadorian Andes is farther from the Earth's center than any other location on the Earth's surface, due to the equatorial bulge resulting from the Earth's rotation. The world's highest volcanoes are in the Andes, including Ojos del Salado on the Chile-Argentina border, which rises to 6,893 m (22,615 ft).

The Andes are also part of the American Cordillera, a chain of mountain ranges (cordillera) that consists of an almost continuous sequence of mountain ranges that form the western "backbone" of North America, Central America, South America and Antarctica.

"Cono de Arita" in the Puna de Atacama, Salta (Argentina)

Aconcagua

Etymology

The etymology of the word Andes has been debated. The majority consensus is that it derives from the Quechua word anti, which means "east" as in Antisuyu (Quechua for "east region"), one of the four regions of the Inca Empire.

Geography

Aerial view of Valle Carbajal in the Fuegian Andes

The Andes can be divided into three sections:

- The Southern Andes (south of Llullaillaco) in Argentina and Chile;

- The Central Andes in Peru, and Bolivia; and

- The Northern Andes in Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador.

In the northern part of the Andes, the isolated Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta range is often considered to be part of the Andes. The term cordillera comes from the Spanish word "cordel", meaning "rope". The Andes range is about 200 km (124 mi) wide throughout its length, except in the Bolivian flexure where it is about 640 kilometres (398 mi) wide. The Leeward Antilles islands Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, which lie in the Caribbean Sea

off the coast of Venezuela, were thought to represent the submerged

peaks of the extreme northern edge of the Andes range, but ongoing

geological studies indicate that such a simplification does not do

justice to the complex tectonic boundary between the South American and

Caribbean plates.

Geology

The Andes are a Mesozoic–Tertiary orogenic belt of mountains along the Pacific Ring of Fire, a zone of volcanic activity that encompasses the Pacific rim of the Americas as well as the Asia-Pacific region. The Andes are the result of tectonic plate processes, caused by the subduction of oceanic crust beneath the South American Plate.

It is the result of a convergent plate boundary between the Nazca Plate

and the South American Plate. The main cause of the rise of the Andes

is the compression of the western rim of the South American Plate due to the subduction of the Nazca Plate and the Antarctic Plate. To the east, the Andes range is bounded by several sedimentary basins, such as Orinoco, Amazon Basin, Madre de Dios and Gran Chaco, that separate the Andes from the ancient cratons in eastern South America. In the south, the Andes share a long boundary with the former Patagonia Terrane. To the west, the Andes end at the Pacific Ocean, although the Peru-Chile trench

can be considered their ultimate western limit. From a geographical

approach, the Andes are considered to have their western boundaries

marked by the appearance of coastal lowlands and a less rugged

topography. The Andes Mountains also contain large quantities of iron

ore located in many mountains within the range.

The Andean orogen has a series of bends or oroclines. The Bolivian Orocline is a seaward concave bending in the coast of South America and the Andes Mountains at about 18° S. At this point, the orientation of the Andes turns from Northwest in Peru to South in Chile and Argentina. The Andean segment north and south of the orocline have been rotated 15° to 20° counter clockwise and clockwise respectively. The Bolivian Orocline area overlaps with the area of maximum width of the Altiplano Plateau and according to Isacks (1988) the orocline is related to crustal shortening. The specific point at 18° S where the coastline bends is known as the "Arica Elbow".

Further south lies the Maipo Orocline a more subtle orocline between

30° S and 38°S with a seaward-concave break in trend at 33° S. Near the southern tip of the Andes lies the Patagonian orocline.

Orogeny

The western rim of the South American Plate has been the place of several pre-Andean orogenies since at least the late Proterozoic and early Paleozoic, when several terranes and microcontinents collided and amalgamated with the ancient cratons of eastern South America, by then the South American part of Gondwana.

The formation of the modern Andes began with the events of the Triassic when Pangaea began the break up that resulted in developing several rifts. The development continued through the Jurassic Period. It was during the Cretaceous Period that the Andes began to take their present form, by the uplifting, faulting and folding of sedimentary and metamorphic

rocks of the ancient cratons to the east. The rise of the Andes has not

been constant, as different regions have had different degrees of

tectonic stress, uplift, and erosion.

Tectonic forces above the subduction zone along the entire west coast of South America where the Nazca Plate and a part of the Antarctic Plate are sliding beneath the South American Plate continue to produce an ongoing orogenic event resulting in minor to major earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to this day. In the extreme south, a major transform fault separates Tierra del Fuego from the small Scotia Plate. Across the 1,000 km (620 mi) wide Drake Passage lie the mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula south of the Scotia Plate which appear to be a continuation of the Andes chain.

The regions immediately east of the Andes experience a series of changes resulting from the Andean orogeny. Parts of the Sunsás Orogen in Amazonian craton disappeared from the surface of earth being overridden by the Andes.

The Sierras de Córdoba, where the effects of the ancient Pampean orogeny can be observed, owe their modern uplift and relief to the Andean orogeny in the Tertiary. Further south in southern Patagonia the onset of the Andean orogeny caused the Magallanes Basin to evolve from being an extensional back-arc basin in the Mesozoic to being a compressional foreland basin in the Cenozoic.

Volcanism

Rift valley near Quilotoa, Ecuador

This photo from the ISS

shows the high plains of the Andes Mountains in the foreground, with a

line of young volcanoes facing the much lower Atacama Desert

The Andes range has many active volcanoes distributed in four

volcanic zones separated by areas of inactivity. The Andean volcanism is

a result of subduction

of the Nazca Plate and Antarctic Plate underneath the South American

Plate. The belt is subdivided into four main volcanic zones that are

separated from each other by volcanic gaps. The volcanoes of the belt

are diverse in terms of activity style, products and morphology. While

some differences can be explained by which volcanic zone a volcano

belongs to, there are significant differences inside volcanic zones and

even between neighbouring volcanoes. Despite being a type location for calc-alkalic

and subduction volcanism, the Andean Volcanic Belt has a large range of

volcano-tectonic settings, such as rift systems and extensional zones,

transpressional faults, subduction of mid-ocean ridges and seamount chains apart from a large range of crustal thicknesses and magma ascent paths, and different amount of crustal assimilations.

Ore deposits and evaporates

The Andes Mountains host large ore and salt deposits and some of their eastern fold and thrust belt acts as traps for commercially exploitable amounts of hydrocarbons. In the forelands of the Atacama desert some of the largest porphyry copper mineralizations occurs making Chile and Peru the first and second largest exporters of copper in the world. Porphyry copper in the western slopes of the Andes has been generated by hydrothermal fluids (mostly water) during the cooling of plutons

or volcanic systems. The porphyry mineralization further benefited from

the dry climate that let them largely out of the disturbing actions of meteoric water. The dry climate in the central western Andes has also led to the creation of extensive saltpeter deposits which were extensively mined until the invention of synthetic nitrates. Yet another result of the dry climate are the salars of Atacama and Uyuni, the first one being the largest source of lithium today and the second the world's largest reserve of the element. Early Mesozoic and Neogene plutonism in Bolivia's Cordillera Central created the Bolivian tin belt as well as the famous, now depleted, deposits of Cerro Rico de Potosí.

Climate and hydrology

Central Andes

Bolivian Andes

The climate in the Andes varies greatly depending on latitude,

altitude, and proximity to the sea. Temperature, atmospheric pressure

and humidity decrease in higher elevations. The southern section is

rainy and cool, the central section is dry. The northern Andes are

typically rainy and warm, with an average temperature of 18 °C (64 °F)

in Colombia. The climate is known to change drastically in rather short

distances. Rainforests

exist just miles away from the snow-covered peak Cotopaxi. The

mountains have a large effect on the temperatures of nearby areas. The snow line

depends on the location. It is at between 4,500 and 4,800 m (14,800 and

15,700 ft) in the tropical Ecuadorian, Colombian, Venezuelan, and

northern Peruvian Andes, rising to 4,800–5,200 m (15,700–17,100 ft) in

the drier mountains of southern Peru south to northern Chile south to

about 30°S, then descending to 4,500 m (14,760 ft) on Aconcagua at 32°S,

2,000 m (6,600 ft) at 40°S, 500 m (1,640 ft) at 50°S, and only 300 m

(980 ft) in Tierra del Fuego at 55°S; from 50°S, several of the larger glaciers descend to sea level.

The Andes of Chile and Argentina can be divided in two climatic and glaciological zones: the Dry Andes and the Wet Andes. Since the Dry Andes extend from the latitudes of Atacama Desert to the area of Maule River,

precipitation is more sporadic and there are strong temperature

oscillations. The line of equilibrium may shift drastically over short

periods of time, leaving a whole glacier in the ablation area or in the accumulation area.

In the high Andes of central Chile and Mendoza Province, rock glaciers are larger and more common than glaciers; this is due to the high exposure to solar radiation.

Though precipitation increases with the height, there are

semiarid conditions in the nearly 7,000-metre (23,000 ft) highest

mountains of the Andes. This dry steppe climate is considered to be

typical of the subtropical position at 32–34° S. The valley bottoms have

no woods, just dwarf scrub. The largest glaciers, as e.g. the Plomo

glacier and the Horcones glaciers, do not even reach 10 km (6.2 mi) in

length and have an only insignificant ice thickness. At glacial times,

however, c. 20,000 years ago, the glaciers were over ten times longer.

On the east side of this section of the Mendozina Andes, they flowed

down to 2,060 m (6,760 ft) and on the west side to about 1,220 m

(4,000 ft) above sea level.

The massifs of Cerro Aconcagua (6,961 m (22,838 ft)), Cerro Tupungato

(6,550 m (21,490 ft)) and Nevado Juncal (6,110 m (20,050 ft)) are tens

of kilometres away from each other and were connected by a joint ice

stream network. The Andes' dendritic glacier arms, i.e. components of

valley glaciers, were up to 112.5 km (69.9 mi) long, over 1,250 m

(4,100 ft) thick and overspanned a vertical distance of 5,150 m

(16,900 ft). The climatic glacier snowline (ELA) was lowered from

4,600 m (15,100 ft) to 3,200 m (10,500 ft) at glacial times.

Flora

Laguna de Sonso tropical dry forest in Northern Andes

The Andean region cuts across several natural and floristic regions due to its extension from Caribbean Venezuela to cold, windy and wet Cape Horn passing through the hyperarid Atacama Desert. Rainforests and tropical dry forests used to encircle much of the northern Andes but are now greatly diminished, especially in the Chocó

and inter-Andean valleys of Colombia. Opposite of the humid Andean

slopes are the relatively dry Andean slopes in most of western Peru,

Chile and Argentina. Along with several Interandean Valles, they are typically dominated by deciduous woodland, shrub and xeric vegetation, reaching the extreme in the slopes near the virtually lifeless Atacama Desert.

About 30,000 species of vascular plants live in the Andes, with roughly half being endemic to the region, surpassing the diversity of any other hotspot. The small tree Cinchona pubescens, a source of quinine which is used to treat malaria, is found widely in the Andes as far south as Bolivia. Other important crops that originated from the Andes are tobacco and potatoes. The high-altitude Polylepis

forests and woodlands are found in the Andean areas of Colombia,

Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile. These trees, by locals referred to as

Queñua, Yagual and other names, can be found at altitudes of 4,500 m

(14,760 ft) above sea level. It remains unclear if the patchy

distribution of these forests and woodlands is natural, or the result of

clearing which began during the Incan period. Regardless, in modern times the clearance has accelerated, and the trees are now considered to be highly endangered, with some believing that as little as 10% of the original woodland remains.

Fauna

A male Andean cock-of-the-rock, a species found in humid Andean forests and the national bird of Peru

The Andes are rich in fauna: With almost 1,000 species, of which roughly 2/3 are endemic to the region, the Andes are the most important region in the world for amphibians.

The diversity of animals in the Andes is high, with almost 600 species of mammals (13% endemic), more than 1,700 species of birds (about 1/3 endemic), more than 600 species of reptile (about 45% endemic), and almost 400 species of fish (about 1/3 endemic).

The vicuña and guanaco can be found living in the Altiplano, while the closely related domesticated llama and alpaca are widely kept by locals as pack animals and for their meat and wool. The crepuscular (active during dawn and dusk) chinchillas, two threatened members of the rodent order, inhabit the Andes' alpine regions. The Andean condor, the largest bird of its kind in the Western Hemisphere, occurs throughout much of the Andes but generally in very low densities. Other animals found in the relatively open habitats of the high Andes include the huemul, cougar, foxes in the genus Pseudalopex, and, for birds, certain species of tinamous (notably members of the genus Nothoprocta), Andean goose, giant coot, flamingos (mainly associated with hypersaline lakes), lesser rhea, Andean flicker, diademed sandpiper-plover, miners, sierra-finches and diuca-finches.

Lake Titicaca hosts several endemics, among them the highly endangered Titicaca flightless grebe and Titicaca water frog. A few species of hummingbirds, notably some hillstars, can be seen at altitudes above 4,000 m (13,100 ft), but far higher diversities can be found at lower altitudes, especially in the humid Andean forests ("cloud forests") growing on slopes in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and far northwestern Argentina. These forest-types, which includes the Yungas and parts of the Chocó, are very rich in flora and fauna, although few large mammals exist, exceptions being the threatened mountain tapir, spectacled bear and yellow-tailed woolly monkey.

Birds of humid Andean forests include mountain-toucans, quetzals and the Andean cock-of-the-rock, while mixed species flocks dominated by tanagers and furnariids commonly are seen – in contrast to several vocal but typically cryptic species of wrens, tapaculos and antpittas.

A number of species such as the royal cinclodes and white-browed tit-spinetail are associated with Polylepis, and consequently also threatened.

Human activity

The Andes Mountains form a north-south axis of cultural influences. A

long series of cultural development culminated in the expansion of the Inca civilization and Inca Empire in the central Andes during the 15th century. The Incas formed this civilization through imperialistic militarism as well as careful and meticulous governmental management. The government sponsored the construction of aqueducts and roads in addition to preexisting installations. Some of these constructions are still in existence today.

Devastated by European diseases to which they had no immunity and civil wars, in 1532 the Incas were defeated by an alliance composed of tens of thousands of allies from nations they had subjugated (e.g. Huancas, Chachapoyas, Cañaris) and a small army of 180 Spaniards led by Francisco Pizarro. One of the few Inca sites the Spanish never found in their conquest was Machu Picchu,

which lay hidden on a peak on the eastern edge of the Andes where they

descend to the Amazon. The main surviving languages of the Andean

peoples are those of the Quechua and Aymara language families. Woodbine Parish and Joseph Barclay Pentland surveyed a large part of the Bolivian Andes from 1826 to 1827.

Cities

La Paz, Bolivia is the highest capital city in the world

In modern times, the largest cities in the Andes are Bogotá, Colombia, with a population of about eight million, Santiago, Chile, and Medellin, Colombia and Cali. Lima is a coastal city adjacent to the Andes and is the largest city of all Andean countries. It is the seat of the Andean Community of Nations.

La Paz, Bolivia's

seat of government, is the highest capital city in the world, at an

elevation of approximately 3,650 m (11,975 ft). Parts of the La Paz

conurbation, including the city of El Alto, extend up to 4,200 m (13,780 ft).

Other cities in or near the Andes include Arequipa, Cusco, Huancayo, Cajamarca, Juliaca, Huánuco, Huaraz, and Puno in Peru; Quito, Cuenca, Ambato, Loja, Riobamba, and Ibarra in Ecuador; Cochabamba, Oruro, Sucre, and Tarija in Bolivia; Calama and Rancagua in Chile; Armenia, Cúcuta, Bucaramanga, Ibagué, Pereira, Pasto, Palmira, Popayán, Tunja, Villavicencio, and Manizales in Colombia; and Barquisimeto, San Cristóbal, Mérida, and Valera in Venezuela and Mendoza, Tucumán, Salta, and San Juan in Argentina. The cities of Caracas, Valencia, and Maracay are in the Venezuelan Coastal Range, which is a debatable extension of the Andes at the northern extreme of South America.

Transportation

Cities and large towns are connected with asphalt-paved roads, while smaller towns are often connected by dirt roads, which may require a four-wheel-drive vehicle.

The rough terrain has historically put the costs of building highways and railroads that cross the Andes out of reach of most neighboring countries, even with modern civil engineering practices. For example, the main crossover of the Andes between Argentina and Chile is still accomplished through the Paso Internacional Los Libertadores. Only recently the ends of some highways that came rather close to one another from the east and the west have been connected. Much of the transportation of passengers is done via aircraft.

However, there is one railroad that connects Chile with Peru via

the Andes, and there are others that make the same connection via

southern Bolivia. See railroad maps of that region.

There are multiple highways in Bolivia that cross the Andes. Some of these were built during a period of war between Bolivia and Paraguay,

in order to transport Bolivian troops and their supplies to the war

front in the lowlands of southeastern Bolivia and western Paraguay.

For decades, Chile claimed ownership of land on the eastern side

of the Andes. However, these claims were given up in about 1870 during

the War of the Pacific between Chile, the allied Bolivia and Peru, in a diplomatic deal to keep Peru out of the war. The Chilean Army and Chilean Navy

defeated the combined forces of Bolivia and Peru, and Chile took over

Bolivia's only province on the Pacific Coast, some land from Peru that

was returned to Peru decades later. Bolivia has been a completely landlocked country ever since. It mostly uses seaports in eastern Argentina and Uruguay for international trade because its diplomatic relations with Chile have been suspended since 1978.

Because of the tortuous terrain in places, villages and towns in the mountains—to which travel via motorized vehicles is of little use—are still located in the high Andes of Chile, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador. Locally, the relatives of the camel, the llama, and the alpaca continue to carry out important uses as pack animals, but this use has generally diminished in modern times. Donkeys, mules, and horses are also useful.

Agriculture

Peruvian farmers sowing maize and beans

The ancient peoples of the Andes such as the Incas have practiced irrigation techniques for over 6,000 years. Because of the mountain slopes, terracing

has been a common practice. Terracing, however, was only extensively

employed after Incan imperial expansions to fuel their expanding realm.

The potato holds a very important role as an internally consumed staple crop. Maize was also an important crop for these people, and was used for the production of chicha, important to Andean native people. Currently, tobacco, cotton and coffee are the main export crops. Coca, despite eradication programmes in some countries, remains an important crop for legal local use in a mildly stimulating herbal tea, and, both controversially and illegally, for the production of cocaine.

Irrigation

Irrigating land in the Peruvian Andes

In unirrigated land, pasture

is the most common type of land use. In the rainy season (summer), part

of the rangeland is used for cropping (mainly potatoes, barley, broad

beans and wheat).

Irrigation is helpful in advancing the sowing data of the summer

crops which guarantees an early yield in the period of food shortage.

Also, by early sowing, maize can be cultivated higher up in the

mountains (up to 3,800 m (12,500 ft)). In addition it makes cropping in

the dry season (winter) possible and allows the cultivation of frost

resistant vegetable crops like onion and carrot.

Mining

Chilean huasos, 19th century

The Andes rose to fame for their mineral wealth during the Spanish conquest of South America. Although Andean Amerindian peoples crafted ceremonial jewelry of gold and other metals, the mineralizations of the Andes were first mined in large scale after the Spanish arrival. Potosí in present-day Bolivia and Cerro de Pasco in Peru were one of the principal mines of the Spanish Empire in the New World. Río de la Plata and Argentina derive their names from the silver of Potosí.

Currently, mining in the Andes of Chile and Peru places these countries as the first and third major producers of copper in the world. Peru also contains the 4th largest goldmine in the world: the Yanacocha. The Bolivian Andes produce principally tin although historically silver mining had a huge impact on the economy of 17th century Europe.

There is a long history of mining in the Andes, from the Spanish silver mines in Potosí in the 16th century to the vast current porphyry copper deposits of Chuquicamata and Escondida in Chile and Toquepala in Peru. Other metals including iron, gold and tin in addition to non-metallic resources are important.