The Golden toad of Monteverde, Costa Rica, was among the first casualties of amphibian declines. Formerly abundant, it was last seen in 1989.

The decline in amphibian populations is an ongoing mass extinction of amphibian species worldwide. Since the 1980s, decreases in amphibian populations, including population crashes and mass localized extinctions, have been observed in locations all over the world. These declines are known as one of the most critical threats to global biodiversity, and several causes are believed to be involved, including disease, habitat destruction and modification, exploitation, pollution, pesticide use, introduced species, and ultraviolet-B

radiation (UV-B). However, many of the causes of amphibian declines are

still poorly understood, and the topic is currently a subject of much

ongoing research. Calculations based on extinction rates suggest that

the current extinction rate of amphibians could be 211 times greater

than the background extinction rate and the estimate goes up to 25,000–45,000 times if endangered species are also included in the computation.

Although scientists began observing reduced populations of

several European amphibian species already in the 1950s, awareness of

the phenomenon as a global problem and its subsequent classification as a

modern-day mass extinction only dates from the 1980s. By 1993, more

than 500 species of frogs and salamanders present on all five continents

were in decline. Today, the phenomenon of declining amphibian

populations affects thousands of species in all types of ecosystems and

is thus recognized as one of the most severe examples of the Holocene extinction, with severe implications for global biodiversity.

Background

In the past three decades, declines in populations of amphibians (the class of organisms that includes frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians)

have occurred worldwide. In 2004, the results were published of the

first worldwide assessment of amphibian populations, the Global

Amphibian Assessment. This found that 32% of species were globally

threatened, at least 43% were experiencing some form of population

decrease, and that between 9 and 122 species have become extinct since

1980. As of 2010, the IUCN Red List, which incorporates the Global Amphibian Assessment and subsequent updates, lists 486 amphibian species as "Critically Endangered".

Despite the high risk this group faces, recent evidence suggests the

public is growing largely indifferent to this and other environmental

problems, posing serious problems for conservationists and environmental

workers alike.

Habitat loss, disease and climate change are thought to be responsible for the drastic decline in populations in recent years.

Declines have been particularly intense in the western United States, Central America, South America, eastern Australia and Fiji

(although cases of amphibian extinctions have appeared worldwide).

While human activities are causing a loss of much of the world's

biodiversity, amphibians appear to be suffering much greater effects

than other classes of organism. Because amphibians generally have a

two-staged life cycle consisting of both aquatic (larvae) and terrestrial (adult) phases, they are sensitive to both terrestrial and aquatic environmental effects. Because their skins are highly permeable, they may be more susceptible to toxins in the environment than other organisms such as birds or mammals. Many scientists believe that amphibians serve as "canaries in a coal mine," and that declines in amphibian populations and species indicate that other groups of animals and plants will soon be at risk.

Declines in amphibian populations were first widely recognized in the late 1980s, when a large gathering of herpetologists reported noticing declines in populations in amphibians across the globe. Among these species, the Golden toad (Bufo periglenes) endemic to Monteverde, Costa Rica,

featured prominently. It was the subject of scientific research until

populations suddenly crashed in 1987 and it had disappeared completely

by 1989. Other species at Monteverde, including the Monteverde Harlequin Frog (Atelopus varius),

also disappeared at the same time. Because these species were located

in the pristine Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, and these extinctions

could not be related to local human activities, they raised particular

concern among biologists.

Initial skepticism

When

amphibian declines were first presented as a conservation issue in the

late 1980s, some scientists remained unconvinced of the reality and

gravity of the conservation issue.

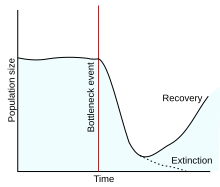

Some biologists argued that populations of most organisms, amphibians

included, naturally vary through time. They argued that the lack of

long-term data on amphibian populations made it difficult to determine

whether the anecdotal declines reported by biologists were worth the

(often limited) time and money of conservation efforts.

However, since this initial skepticism, biologists have come to a

consensus that declines in amphibian populations are a real and severe

threat to biodiversity.

This consensus emerged with an increase in the number of studies that

monitored amphibian populations, direct observation of mass mortality in

pristine sites that lacked apparent cause, and an awareness that

declines in amphibian populations are truly global in nature.

Potential causes

Numerous

potential explanations for amphibian declines have been proposed. Most

or all of these causes have been associated with some population

declines, so each cause is likely to affect in certain circumstances but

not others. Many of the causes of amphibian declines are well

understood, and appear to affect other groups of organisms as well as

amphibians. These causes include habitat modification and

fragmentation, introduced predators or competitors, introduced species,

pollution, pesticide use, or over-harvesting. However, many amphibian

declines or extinctions have occurred in pristine habitats where the

above effects are not likely to occur. The causes of these declines are

complex, but many can be attributed to emerging diseases, climate

change, increased ultraviolet-B radiation, or long-distance transmission

of chemical contaminants by wind.

Artificial lighting has been suggested as another potential

cause. Insects are attracted to lights making them scarcer within the

amphibian habitats.

Habitat modification

Habitat

modification or destruction is one of the most dramatic issues

affecting amphibian species worldwide. As amphibians generally need

aquatic and terrestrial habitats to survive, threats to either habitat

can affect populations. Hence, amphibians may be more vulnerable to

habitat modification than organisms that only require one habitat type.

Large scale climate changes may further be modifying aquatic habitats,

preventing amphibians from spawning altogether.

Habitat fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation occurs when habitats are isolated by habitat

modification, such as when a small area of forest is completely

surrounded by agricultural fields. Small populations that survive

within such fragments are often susceptible to inbreeding, genetic drift, or extinction due to small fluctuations in the environment.

Pollution and chemical contaminants

There is evidence of chemical pollutants causing frog developmental deformities (extra limbs, or malformed eyes). Pollutants have varying effects on frogs. Some alter the central nervous system; others like atrazine

cause a disruption in the production and secretion of hormones.

Experimental studies have also shown that exposure to commonly used

herbicides such as glyphosate (Tradename Roundup) or insecticides such as malathion or carbaryl greatly increase mortality of tadpoles.

Additional studies have indicated that terrestrial adult stages of

amphibians are also susceptible to non-active ingredients in Roundup,

particularly POEA, which is a surfactant.

Atrazine has been shown to cause male tadpoles of African clawed frogs

to become hermaphroditic with development of both male and female

organs. Such feminization has been reported in many parts of the world.

In a study conducted in a laboratory at Uppsala University in Sweden,

more than 50% of frogs exposed to levels of estrogen-like pollutants

existing in natural bodies of water in Europe and the United States

became females. Tadpoles exposed even to the weakest concentration of

estrogen were twice as likely to become females while almost all of the

control group given the heaviest dose became female.

While most pesticide effects are likely to be local and restricted to areas near agriculture, there is evidence from the Sierra Nevada mountains of the western United States that pesticides are traveling long distances into pristine areas, including Yosemite National Park in California.

Some recent evidence points to ozone as a possible contributing factor to the worldwide decline of amphibians.

Ozone depletion, ultraviolet radiation and cloud cover

Like many other organisms, increasing ultraviolet-B (UVB) radiation due to stratospheric ozone depletion and other factors may harm the DNA of amphibians, particularly their eggs.

The amount of damage depends upon the life stage, the species type and

other environmental parameters. Salamanders and frogs that produce less photolyase,

an enzyme that counteracts DNA damage from UVB, are more susceptible to

the effects of loss of the ozone layer. Exposure to ultraviolet

radiation may not kill a particular species or life stage but may cause

sublethal damage.

More than three dozen species of amphibians have been studied,

with severe effects reported in more than 40 publications in

peer-reviewed journals representing authors from North America, Europe

and Australia. Experimental enclosure approaches to determine UVB

effects on egg stages have been criticized; for example, egg masses were

placed at water depths much shallower than is typical for natural

oviposition sites. While UVB radiation is an important stressor for

amphibians, its effect on the egg stage may have been overstated.

Anthropogenic climate change has likely exerted a major effect on

amphibian declines. For example, in the Monteverde Cloud Forest, a

series of unusually warm years led to the mass disappearances of the

Monteverde Harlequin frog and the Golden Toad. An increased level of cloud cover, a result of geoengineering

and global warming, which has warmed the nights and cooled daytime

temperatures, has been blamed for facilitating the growth and

proliferation of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (the causative agent of the fungal infection chytridiomycosis).

An adult male Ecnomiohyla rabborum in the Atlanta Botanical Garden, a species ravaged by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis

in its native habitat. It was the last known surviving member of its

species, and with its death on Sept 28, 2016, the species is believed to

be extinct.

Although the immediate cause of the die offs was the chytrid, climate

change played a pivotal role in the extinctions. Researchers included

this subtle connection in their inclusive climate-linked epidemic

hypothesis, which acknowledged climatic change as a key factor in

amphibian extinctions both in Costa Rica and elsewhere.

New evidence has shown global warming to also be capable of directly degrading toads' body condition and survivorship.

Additionally, the phenomenon often colludes with landscape

alteration, pollution, and species invasions to effect amphibian

extinctions.

Disease

A number of diseases have been related to mass die-offs or declines in populations of amphibians, including "red-leg" disease (Aeromonas hydrophila), Ranavirus (family Iridoviridae), Anuraperkinsus, and chytridiomycosis.

It is not entirely clear why these diseases have suddenly begun to

affect amphibian populations, but some evidence suggests that these

diseases may have been spread by humans, or may be more virulent when

combined with other environmental factors.

Trematodes

Trematode cyst-infected Pacific Tree Frog (Hyla regilla)

with supernumerary limbs, from La Pine, Deschutes County, Oregon,

1998-9. This 'category I' deformity (polymelia) is believed to be caused

by the trematode cyst infection. The cartilage is stained blue and

calcified bones in red.

There is considerable evidence that parasitic trematode platyhelminths (a type of fluke) have contributed to developmental abnormalities and population declines of amphibians in some regions. These trematodes of the genus Ribeiroia

have a complex life cycle with three host species. The first host

includes a number of species of aquatic snails. The early larval stages

of the trematodes then are transmitted into aquatic tadpoles, where the

metacercariae (larvae) encyst in developing limb buds. These encysted

life stages produce developmental abnormalities in post-metamorphic

frogs, including additional or missing limbs. These abnormalities increase frog predation by aquatic birds, the final host of the trematode.

Pacific Tree Frog with limb malformation induced by Ribeiroia ondatrae

A study showed that high levels of nutrients used in farming and

ranching activities fuel parasite infections that have caused frog

deformities in ponds and lakes across North America. The study showed

increased levels of nitrogen and phosphorus cause sharp hikes in the

abundance of trematodes, and that the parasites subsequently form cysts

in the developing limbs of tadpoles causing missing limbs, extra limbs

and other severe malformations including five or six extra or even no

limbs.

Chytridiomycosis

A chytrid-infected frog

In 1998, following large-scale frog deaths in Australia and Central

America, research teams in both areas came up with identical results: a

previously undescribed species of pathogenic fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. It is now clear that many recent extinctions of amphibians in Australia and the Americas are linked to this fungus. This fungus belongs to a family of saprobes known as chytrids that are not generally pathogenic.

The disease caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is called chytridiomycosis. Frogs infected by this disease generally show skin lesions and hyperkeratosis,

and it is believed that death occurs because of interference with skin

functions including maintenance of fluid balance, electrolyte homeostasis, respiration and role as a barrier to infections. The time from infection to death has been found to be 1–2 weeks in experimental tests, but infected animals can carry the fungus as long as 220 days. There are several hypotheses on the transmission and vectors of the fungus.

Subsequent research has established that the fungus has been

present in Australia since at least 1978, and present in North America

since at least the 1970s. The first known record of chytrid infection

in frogs is in the African Clawed Frog, Xenopus laevis.

Because Xenopus are sold in pet shops and used in laboratories

around the world, it is possible that the chytrid fungus may have been

exported from Africa.

Introduced predators

Non-native predators and competitors have also been found to affect the viability of frogs in their habitats. The mountain yellow-legged frog which typically inhabits the Sierra Nevada lakes have seen a decline in numbers due to stocking of non-native fish (trout) for recreational fishing. The developing tadpoles and froglets fall prey to the fish in large numbers. This interference in the frog's three-year metamorphosis is causing a decline that is manifest throughout their ecosystem.

Increased noise levels

Frogs

and toads are highly vocal, and their reproductive behaviour often

involves the use of vocalizations. There have been suggestions that

increased noise levels caused by human activities may be contributing to

their declines. In a study in Thailand, increased ambient noise levels were shown to decrease calling in some species and to cause an increase in others. This has, however, not been shown to be a cause for the widespread decline.

Symptoms of stressed populations

Amphibian

populations in the beginning stages of decline often exude a number of

signs, which may potentially be used to identify at-risk segments in

conservation efforts. One such sign is developmental instability, which

has been proven as evidence of environmental stress.

This environmental stress can potentially raise susceptibility to

diseases such as chytridiomycosis, and thus lead to amphibian declines.

In a study conducted in Queensland, Australia, for example, populations of two amphibian species, Litoria nannotis and Litoria genimaculata,

were found to exhibit far greater levels of limb asymmetry in

pre-decline years than in control years, the latter of which preceded

die offs by an average of 16 years.

Learning to identify such signals in the critical period before

population declines occur might greatly improve conservation efforts.

Conservation measures

The first response to reports of declining amphibian populations was

the formation of the Declining Amphibian Population Task Force (DAPTF)

in 1990. DAPFT led efforts for increased amphibian population monitoring

in order to establish the extent of the problem, and established

working groups to look at different issues. Results were communicated through the newsletter Froglog.

Much of this research went into the production of the first

Global Amphibian Assessment (GAA), which was published in 2004 and

assessed every known amphibian species against the IUCN Red List

criteria. This found that approximately one third of amphibian species

were threatened with extinction.

As a result of these shocking findings an Amphibian Conservation Summit

was held in 2005, because it was considered "morally irresponsible to

document amphibian declines and extinctions without also designing and

promoting a response to this global crisis".

Outputs from the Amphibian Conservation Summit included the first Amphibian Conservation Action Plan (ACAP) and to merge the DAPTF and the Global Amphibian Specialist Group into the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (ASG).

The ACAP established the elements required to respond to the crisis,

including priority actions on a variety of thematic areas. The ASG is a

global volunteer network of dedicated experts who work to provide the

scientific foundation for effective amphibian conservation action around

the world.

On 16 February 2007, scientists worldwide met in Atlanta, U.S., to form a group called the Amphibian Ark to help save more than 6,000 species of amphibians from disappearing by starting captive breeding programmes.

Areas with noticed frog extinctions, like Australia, have few

policies that have been created to prevent the extinction of these

species. However, local initiatives have been placed where conscious

efforts to decrease global warming will also turn into a conscious

effort towards saving the frogs. In South America, where there is also

an increased decline of amphibian populations, there is no set policy to

try to save frogs. Some suggestions would include getting entire

governments to place a set of rules and institutions as a source of

guidelines that local governments have to abide by.

A critical issue is how to design protected areas for amphibians

which will provide suitable conditions for their survival. Conservation

efforts through the use of protected areas have shown to generally be a

temporary solution to population decline and extinction because the

amphibians become inbred. It is crucial for most amphibians to maintain a high level of genetic variation through large and more diverse environments.

Education of local people to protect amphibians is crucial, along

with legislation for local protection and limiting the use of toxic

chemicals, including some fertilizers and pesticides in sensitive

amphibian areas.