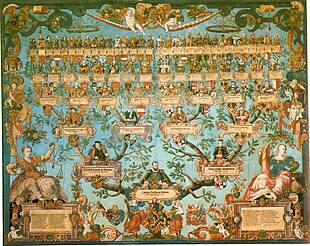

The family tree of Ludwig Herzog von Württemberg (ruled 1568–1593)

Genealogy (from Greek: γενεαλογία genealogia "the making of a pedigree") is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages.

Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis,

and other records to obtain information about a family and to

demonstrate kinship and pedigrees

of its members. The results are often displayed in charts or written as

narratives. Although generally used interchangeably, the traditional

definition of "genealogy" begins with a person who is usually deceased

and traces his or her descendants forward in time, whereas, "family

history" begins with a person who is usually living and traces his or

her ancestors. Both the National Genealogical Society in the United States and the Society of Genealogists in the United Kingdom

state that the word "genealogy" often refers to the scholarly

discipline of researching lineages and connecting generations, whereas

"family history" often refers to biographical studies of ones family,

including family narratives and traditions.

The pursuit of family history and origins tends to be shaped by

several motives, including the desire to carve out a place for one's

family in the larger historical picture, a sense of responsibility to

preserve the past for future generations, and self-satisfaction in

accurate storytelling. Genealogy research is also performed for scholarly or forensic purposes.

Overview

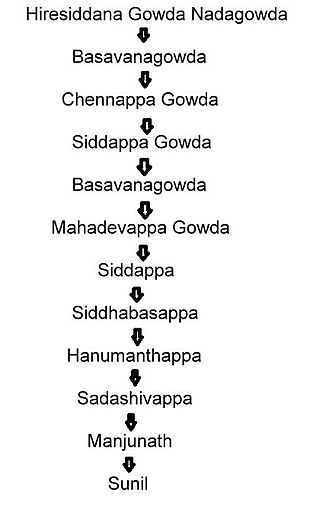

12 generations patrilineage of a Hindu Lingayat male from central Karnataka spanning over 275 years, depicted in descending order

Amateur genealogists typically pursue their own ancestry and that of

their spouses. Professional genealogists may also conduct research for

others, publish books on genealogical methods, teach, or produce their

own databases. They may work for companies that provide software or

produce materials of use to other professionals and to amateurs. Both

try to understand not just where and when people lived, but also their

lifestyles, biographies, and motivations. This often requires—or leads

to—knowledge of antiquated laws, old political boundaries, migration

trends, and historical socioeconomic or religious conditions.

Genealogists sometimes specialize in a particular group, e.g. a Scottish clan; a particular surname, such as in a one-name study; a small community, e.g. a single village or parish, such as in a one-place study; or a particular, often famous, person. Bloodlines of Salem

is an example of a specialized family-history group. It welcomes

members who can prove descent from a participant of the Salem Witch

Trials or who simply choose to support the group.

Genealogists and family historians often join family history societies,

where novices can learn from more experienced researchers. Such

societies generally serve a specific geographical area. Their members

may also index records to make them more accessible, and engage in

advocacy and other efforts to preserve public records and cemeteries.

Some schools engage students in such projects as a means to reinforce

lessons regarding immigration and history. Other benefits include family medical histories with families with serious medical conditions that are hereditary.

The terms "genealogy" and "family history" are often used synonymously, but some offer a slight difference in definition. The Society of Genealogists,

while also using the terms interchangeably, describes genealogy as the

"establishment of a Pedigree by extracting evidence, from valid sources,

of how one generation is connected to the next" and family history as

"a biographical study of a genealogically proven family and of the

community and country in which they lived".

Motivation

Individuals conduct genealogical research for a number of reasons.

Personal or medical interest

Private

individuals do genealogy out of curiosity about their heritage. This

curiosity can be particularly strong among those whose family histories

were lost or unknown due to, for example, adoption or separation from family through divorce, death, or other situations.

In addition to simply wanting to know more about who they are and where

they came from, individuals may research their genealogy to learn about

any hereditary diseases in their family history.

There is a growing interest in family history in the media as a

result of advertising and television shows sponsored by large genealogy

companies such as Ancestry.com. This coupled with easier access to online records and the affordability of DNA tests has both inspired curiosity and allowed those who are curious to easily start investigating their ancestry.

Community or religious obligation

In communitarian

societies, one's identity is defined as much by one's kin network as by

individual achievement, and the question "Who are you?" would be

answered by a description of father, mother, and tribe. New Zealand Māori, for example, learn whakapapa (genealogies) to discover who they are.

Family history plays a part in the practice of some religious belief systems. For example, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has a doctrine of baptism for the dead, which necessitates that members of that faith engage in family history research.

In East Asian countries that were historically shaped by Confucianism, many people follow a practice of ancestor worship as well as genealogical record-keeping. Ancestor's names are inscribed on tablets and placed in shrines, where rituals are performed. Genealogies are also recorded in genealogy books. This practice is rooted in the belief that respect for one's family is a foundation for a healthy society.

Establishing identity

Royal families, both historically and in modern times, keep records of their genealogies in order to establish their right to rule

and determine who will be the next sovereign. For centuries in various

cultures, ones genealogy has been a source of political and social

status.

Some countries and indigenous tribes allow individuals to obtain citizenship based on their genealogy. In Ireland,

for example, an individual can become a citizen if one of their

grandparents was born in Ireland, even if the individual or their

parents were not born there. In societies such as Australia or the

United States, there was by the 20th century growing pride in the

pioneers and nation-builders. Establishing descent from these was, and

is, important to lineage societies such as the Daughters of the American Revolution and The Mayflower Society.

Modern family history explores new sources of status, such as

celebrating the resilience of families that survived generations of

poverty or slavery, or the success of families in integrating across

racial or national boundaries. Some family histories even emphasize

links to celebrity criminals, such as the bushranger Ned Kelly in Australia.

Legal and forensic research

Lawyers involved in probate cases do genealogy to locate heirs of property.

Detectives may perform genealogical research using DNA evidence to identify victims of homicides or perpetrators of crimes.

Scholarly research

Historians and geneticists

may do genealogical research to gain a greater understanding of

specific topics in their respective fields.

Professional genealogists conduct paid genealogical research for any of

the above individuals. They also publish their research in peer-reviewed

journals.

History

A Medieval genealogy traced from Adam and Eve

Historically, in Western societies the focus of genealogy was on the kinship and descent

of rulers and nobles, often arguing or demonstrating the legitimacy of

claims to wealth and power. The term often overlapped with heraldry, in which the ancestry of royalty was reflected in their coats of arms. Modern scholars consider many claimed noble ancestries to be fabrications, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that traced the ancestry of several English kings to the god Woden.

Some family trees have been maintained for considerable periods. The family tree of Confucius has been maintained for over 2,500 years and is listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest extant family tree. The fifth edition of the Confucius Genealogy was printed in 2009 by the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee (CGCC).

Modern times

In

modern times, genealogy became more widespread, with commoners as well

as nobility researching and maintaining their family trees. Genealogy received a boost in the late 1970s with the television broadcast of Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley. His account of his family's descent from the African tribesman Kunta Kinte inspired many others to study their own lines.

With the advent of the Internet,

the number of resources readily accessible to genealogists has vastly

increased, resulting in an explosion of interest in the topic. Genealogy is one of the most popular topics on the Internet. The Internet has become not only a major source of data for genealogists, but also of education and communication.

India

In India, Charans are the Bards who traditionally keep the written genealogy records of various castes. Some notable places where traditional genealogy records are kept include: Hindu genealogy registers at Haridwar (Uttarakhand), Varanasi and Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh), Kurukshetra (Haryana), Trimbakeshwar (Maharashtra), and Chintpurni (Himachal Pradesh).

United States

Genealogical research in the United States was first systematized in the early 19th century, especially by John Farmer (1789–1838).

Before Farmer's efforts, tracing one's genealogy was seen as an attempt

by colonists to secure a measure of social standing within the British

Empire, an aim that was counter to the new republic's egalitarian,

future-oriented ethos.

As Fourth of July celebrations commemorating the Founding Fathers and

the heroes of the Revolutionary War became increasingly popular,

however, the pursuit of 'antiquarianism,' which focused on local

history, became acceptable as a way to honor the achievements of early

Americans.

Farmer capitalized on the acceptability of antiquarianism to frame

genealogy within the early republic's ideological framework of pride in

one's American ancestors. He corresponded with other antiquarians in New

England, where antiquarianism and genealogy were well established, and

became a coordinator, booster, and contributor to the growing movement.

In the 1820s, he and fellow antiquarians began to produce genealogical

and antiquarian tracts in earnest, slowly gaining a devoted audience

among the American people. Though Farmer died in 1839, his efforts led

to the creation of the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), one of New England's oldest and most prominent organizations dedicated to the preservation of public records. NEHGS publishes the New England Historical and Genealogical Register.

The Genealogical Society of Utah, founded in 1894, later became the Family History Department of the LDS Church. The department's research facility, the Family History Library, which Utah.com states is "the largest genealogical library in the world,"

was established to assist in tracing family lineages for special

religious ceremonies which Latter-day Saints believe will seal family

units together for eternity. Latter-day Saints believe that this

fulfilled a biblical prophecy stating that the prophet Elijah would return to "turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers." There is a network of church-operated Family History Centers all over the country and around the world, where volunteers assist the public with tracing their ancestors. Brigham Young University

offers bachelor's degree, minor, and concentration programs in Family

History, and is the only school in North America to offer this.

The American Society of Genealogists

is the scholarly honorary society of the U.S. genealogical field.

Founded by John Insley Coddington, Arthur Adams, and Meredith B. Colket,

Jr., in December 1940, its membership is limited to 50 living fellows.

ASG publishes The Genealogist, a scholarly journal of genealogical research semi-annually since 1980. Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, who bear the post-nominal acronym FASG, have written some of the most notable genealogical materials of the last half-century.

Some of the most notable scholarly American genealogical journals are The American Genealogist, National Genealogical Society Quarterly, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and The Genealogist.

Research process

Genealogical

research is a complex process that uses historical records and

sometimes genetic analysis to demonstrate kinship. Reliable conclusions

are based on the quality of sources, ideally original records, the

information within those sources, ideally primary or firsthand

information, and the evidence that can be drawn, directly or indirectly,

from that information. In many instances, genealogists must skillfully

assemble indirect or circumstantial evidence

to build a case for identity and kinship. All evidence and conclusions,

together with the documentation that supports them, is then assembled

to create a cohesive genealogy or family history.

Genealogists begin their research by collecting family documents and stories. This creates a foundation for documentary research,

which involves examining and evaluating historical records for evidence

about ancestors and other relatives, their kinship ties, and the events

that occurred in their lives. As a rule, genealogists begin with the

present and work backward in time. Historical, social, and family

context is essential to achieving correct identification of individuals

and relationships. Source citation is also important when conducting

genealogical research. To keep track of collected material, family group sheets and pedigree charts are used. Formerly handwritten, these can now be generated by genealogical software.

Genetic analysis

Variations of VNTR allele lengths in 6 individuals

Because a person's DNA contains information that has been passed down relatively unchanged from early ancestors, analysis of DNA is sometimes used for genealogical research. Three DNA types are of particular interest: mitochondrial DNA that we all possess and that is passed down with only minor mutations through the matrilineal (direct female) line; the Y-chromosome, present only in males, which is passed down with only minor mutations through the patrilineal (direct male) line; and the Autosomal DNA,

which is found in the 22 non-gender specific chromosomes (autosomes)

inherited from both parents, which can uncover relatives from any branch

of the family. A genealogical DNA test

allows two individuals to find the probability that they are, or are

not, related within an estimated number of generations. Individual genetic test results are collected in databases to match people descended from a relatively recent common ancestor. See, for example, the Molecular Genealogy Research Project. These tests are limited to either the patrilineal or the matrilineal line.

Collaboration

Most genealogy software programs can export information about persons and their relationships in a standardized format called GEDCOM. In that format it can be shared with other genealogists, added to databases, or converted into family web sites. Social networking service

(SNS) websites allow genealogists to share data and build their family

trees online. Members can upload their family trees and contact other

family historians to fill in gaps in their research. In addition to the

(SNS) websites, there are other resources that encourage genealogists

to connect and share information such as rootsweb.ancestry.com and rsl.rootsweb.ancestry.com.

Volunteerism

Volunteer efforts figure prominently in genealogy. These range from the extremely informal to the highly organized.

On the informal side are the many popular and useful message boards such as Rootschat and mailing lists

on particular surnames, regions, and other topics. These forums can be

used to try to find relatives, request record lookups, obtain research

advice, and much more. Many genealogists participate in loosely

organized projects, both online and off. These collaborations take

numerous forms. Some projects prepare name indexes for records, such as probate cases, and publish the indexes, either online or off. These indexes can be used as finding aids

to locate original records. Other projects transcribe or abstract

records. Offering record lookups for particular geographic areas is

another common service. Volunteers do record lookups or take photos in

their home areas for researchers who are unable to travel.

Those looking for a structured volunteer environment can join one of thousands of genealogical societies worldwide. Most societies have a unique area of focus, such as a particular surname, ethnicity, geographic area, or descendancy from participants in a given historical event.

Genealogical societies are almost exclusively staffed by volunteers and

may offer a broad range of services, including maintaining libraries

for members' use, publishing newsletters, providing research assistance

to the public, offering classes or seminars, and organizing record

preservation or transcription projects.

Software

Gramps is an example of genealogy software.

Genealogy software

is used to collect, store, sort, and display genealogical data. At a

minimum, genealogy software accommodates basic information about

individuals, including births, marriages, and deaths. Many programs

allow for additional biographical information, including occupation,

residence, and notes, and most also offer a method for keeping track of

the sources for each piece of evidence.

Most programs can generate basic kinship charts and reports, allow for

the import of digital photographs and the export of data in the GEDCOM

format (short for GEnealogical Data COMmunication) so that data can be

shared with those using other genealogy software. More advanced features

include the ability to restrict the information that is shared, usually

by removing information about living people out of privacy

concerns; the import of sound files; the generation of family history

books, web pages and other publications; the ability to handle same-sex marriages

and children born out of wedlock; searching the Internet for data; and

the provision of research guidance. Programs may be geared toward a

specific religion, with fields relevant to that religion, or to specific

nationalities or ethnic groups, with source types relevant for those

groups. Online resources involve complex programming and large data

bases, such as censuses.

Records and documentation

A family history page from an antebellum era family Bible

Genealogists use a wide variety of records in their research. To

effectively conduct genealogical research, it is important to understand

how the records were created, what information is included in them, and

how and where to access them.

List of record types

Records that are used in genealogy research include:

- Vital records

- Birth records

- Death records

- Marriage and divorce records

- Adoption records

- Biographies and biographical profiles (e.g. Who's Who)

- Cemetery lists

- Census records

- Religious records

- Baptism or christening

- Brit milah or Baby naming certificates

- Confirmation

- Bar or bat mitzvah

- Marriage

- Funeral or death

- Membership

- City directories[63] and telephone directories

- Coroner's reports

- Court records

- Diaries, personal letters and family Bibles

- DNA tests

- Emigration, immigration and naturalization records

- Hereditary & lineage organization records, e.g. Daughters of the American Revolution records

- Land and property records, deeds

- Medical records

- Military and conscription records

- Newspaper articles

- Obituaries

- Occupational records

- Oral histories

- Passports

- Photographs

- Poorhouse, workhouse, almshouse, and asylum records

- School and alumni association records

- Ship passenger lists

- Social Security (within the US) and pension records

- Tax records

- Tombstones, cemetery records, and funeral home records

- Voter registration records

- Wills and probate records

To keep track of their citizens, governments began keeping records of persons who were neither royalty nor nobility. In England and Germany, for example, such record keeping started with parish registers in the 16th century.

As more of the population was recorded, there were sufficient records

to follow a family. Major life events, such as births, marriages, and

deaths, were often documented with a license, permit, or report.

Genealogists locate these records in local, regional or national offices

or archives and extract information about family relationships and recreate timelines of persons' lives.

In China, India and other Asian countries, genealogy books

are used to record the names, occupations, and other information about

family members, with some books dating back hundreds or even thousands

of years. In the eastern Indian state of Bihar, there is a written tradition of genealogical records among Maithil Brahmins and Karna Kayasthas called "Panjis", dating to the 12th century CE. Even today these records are consulted prior to marriages.

In Ireland, genealogical records were recorded by professional families of senchaidh (historians) until as late as the mid-17th century. Perhaps the most outstanding example of this genre is Leabhar na nGenealach/The Great Book of Irish Genealogies, by Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh (d. 1671), published in 2004.

FamilySearch collections

The

Family History Library, operated by The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-Day Saints, is the world's largest library dedicated to

genealogical research.

The LDS Church has engaged in large-scale microfilming of records of

genealogical value. Its Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah,

houses over 2 million microfiche and microfilms of genealogically

relevant material, which are also available for on-site research at over

4500 Family History Centers worldwide.

FamilySearch's website includes many resources for genealogists: a FamilyTree database, historical records, digitized family history books, resources and indexing for African American genealogy such as slave and bank records, and a Family History Research Wiki containing research guidance articles.

Indexing ancestral Information

Indexing

is the process of transcribing parish records, city vital records, and

other reports, to a digital database for searching. Volunteers and

professionals participate in the indexing process. Since 2006, the

microfilm in the FamilySearch granite mountain vault is in the process

of being digitally scanned, available online, and eventually indexed.

For example, after the 72-year legal limit for releasing personal information for the United States Census was reached in 2012, genealogical groups cooperated to index the 132 million residents registered in the 1940 United States Census.

Between 2006 and 2012, the FamilySearch indexing effort produced more than 1 billion searchable records.

Record loss and preservation

Sometimes

genealogical records are destroyed, whether accidentally or on purpose.

In order to do thorough research, genealogists keep track of which

records have been destroyed so they know when information they need may

be missing. Of particular note for North American genealogy is the 1890 United States Census,

which was destroyed in a fire in 1921. Although fragments survive, most

of the 1890 census no longer exists. Those looking for genealogical

information for families that lived in the United States in 1890 must

rely on other information to fill that gap.

War is another cause of record destruction. During World War II, many European records were destroyed. Communists in China during the Cultural Revolution and in Korea during the Korean War destroyed genealogy books kept by families.

Often records are destroyed due to accident or neglect. Since

genealogical records are often kept on paper and stacked in high-density

storage, they are prone to fire, mold, insect damage, and eventual

disintegration. Sometimes records of genealogical value are deliberately

destroyed by governments or organizations because the records are

considered to be unimportant or a privacy risk. Because of this,

genealogists often organize efforts to preserve records that are at risk

of destruction. FamilySearch

has an ongoing program that assesses what useful genealogical records

have the most risk of being destroyed, and sends volunteers to digitize

such records. In 2017, the government of Sierra Leone

asked FamilySearch for help preserving their rapidly deteriorating

vital records. FamilySearch has begun digitizing the records and making

them available online. The Federation of Genealogical Societies also organized an effort to preserve and digitize United States War of 1812

pension records. In 2010, they began raising funds, which were

contribute by genealogists around the United States and matched by Ancestry.com.

Their goal was achieved and the process of digitization was able to

begin. The digitized records are available for free online.

Types of information

Genealogists

who seek to reconstruct the lives of each ancestor consider all

historical information to be "genealogical" information. Traditionally,

the basic information needed to ensure correct identification of each

person are place names, occupations, family names,

first names, and dates. However, modern genealogists greatly expand

this list, recognizing the need to place this information in its

historical context in order to properly evaluate genealogical evidence

and distinguish between same-name individuals. A great deal of

information is available for British ancestry with growing resources for other ethnic groups.

Family names

Lineage of a family, c1809

Family names are simultaneously one of the most important pieces of

genealogical information, and a source of significant confusion for

researchers.

In many cultures, the name of a person refers to the family to which he or she belongs. This is called the family name, surname, or last name. Patronymics

are names that identify an individual based on the father's name. For

example, Marga Olafsdottir is Marga, daughter of Olaf, and Olaf Thorsson

is Olaf, son of Thor. Many cultures used patronymics before surnames

were adopted or came into use. The Dutch in New York, for example, used

the patronymic system of names until 1687 when the advent of English

rule mandated surname usage. In Iceland, patronymics are used by a majority of the population.

In Denmark and Norway patronymics and farm names were generally in use

through the 19th century and beyond, though surnames began to come into

fashion toward the end of the 19th century in some parts of the country.

Not until 1856 in Denmark and 1923 in Norway were there laws requiring surnames.

The transmission of names across generations, marriages and other

relationships, and immigration may cause difficulty in genealogical

research. For instance, women in many cultures have routinely used their

spouse's surnames. When a woman remarried, she may have changed her

name and the names of her children; only her name; or changed no names.

Her birth name (maiden name) may be reflected in her children's middle names; her own middle name; or dropped entirely.

Children may sometimes assume stepparent, foster parent, or adoptive

parent names. Because official records may reflect many kinds of surname

change, without explaining the underlying reason for the change, the

correct identification of a person recorded identified with more than

one name is challenging. Immigrants to America often Americanized their

names.

Surname data may be found in trade directories, census returns, birth, death, and marriage records.

Given names

Genealogical data regarding given names (first names) is subject to many of the same problems as are family names and place names. Additionally, the use of nicknames

is very common. For example, Beth, Lizzie or Betty are all common for

Elizabeth, and Jack, John and Jonathan may be interchanged.

Middle names provide additional information. Middle names may be

inherited, follow naming customs, or be treated as part of the family

name. For instance, in some Latin cultures, both the mother's family

name and the father's family name are used by the children.

Historically, naming traditions existed in some places and

cultures. Even in areas that tended to use naming conventions, however,

they were by no means universal. Families may have used them some of the

time, among some of their children, or not at all. A pattern might also

be broken to name a newborn after a recently deceased sibling, aunt or

uncle.

An example of a naming tradition from England, Scotland and Ireland:

| Child | Namesake |

| 1st son | paternal grandfather |

| 2nd son | maternal grandfather |

| 3rd son | father |

| 4th son | father's oldest brother |

| 1st daughter | maternal grandmother |

| 2nd daughter | paternal grandmother |

| 3rd daughter | mother |

| 4th daughter | mother's oldest sister |

Another example is in some areas of Germany, where siblings were

given the same first name, often of a favourite saint or local nobility,

but different second names by which they were known (Rufname).

If a child died, the next child of the same gender that was born may

have been given the same name. It is not uncommon that a list of a

particular couple's children will show one or two names repeated.

Personal names have periods of popularity, so it is not uncommon

to find many similarly named people in a generation, and even similarly

named families; e.g., "William and Mary and their children David, Mary,

and John".

Many names may be identified strongly with a particular gender; e.g., William for boys, and Mary for girls. Others may be ambiguous, e.g., Lee, or have only slightly variant spellings based on gender, e.g., Frances (usually female) and Francis (usually male).

Place names

While

the locations of ancestors' residences and life events are core

elements of the genealogist's quest, they can often be confusing. Place

names may be subject to variant spellings by partially literate scribes.

Locations may have identical or very similar names. For example, the

village name Brockton occurs six times in the border area between the English counties of Shropshire and Staffordshire.

Shifts in political borders must also be understood. Parish, county,

and national borders have frequently been modified. Old records may

contain references to farms and villages that have ceased to exist. When

working with older records from Poland, where borders and place names

have changed frequently in past centuries, a source with maps and sample

records such as A Translation Guide to 19th-Century Polish-Language Civil-Registration Documents can be invaluable.

Available sources may include vital records (civil or church

registration), censuses, and tax assessments. Oral tradition is also an

important source, although it must be used with caution. When no source

information is available for a location, circumstantial evidence may

provide a probable answer based on a person's or a family's place of

residence at the time of the event.

Maps and gazetteers are important sources for understanding the

places researched. They show the relationship of an area to neighboring

communities and may be of help in understanding migration patterns. Family tree mapping using online mapping tools such as Google Earth (particularly when used with Historical Map overlays such as those from the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection) assist in the process of understanding the significance of geographical locations.

Dates

It is wise

to exercise extreme caution with dates. Dates are more difficult to

recall years after an event, and are more easily mistranscribed than

other types of genealogical data.

Therefore, one should determine whether the date was recorded at the

time of the event or at a later date. Dates of birth in vital records or

civil registrations and in church records at baptism are generally

accurate because they were usually recorded near the time of the event.

Family Bibles are often a source for dates, but can be written from

memory long after the event. When the same ink and handwriting is used

for all entries, the dates were probably written at the same time and

therefore will be less reliable since the earlier dates were probably

recorded well after the event. The publication date of the Bible also

provides a clue about when the dates were recorded since they could not

have been recorded at any earlier date.

People sometimes reduce their age on marriage, and those under

"full age" may increase their age in order to marry or to join the armed

forces. Census returns are notoriously unreliable for ages or for assuming an approximate death date. Ages over 15 in the 1841 census in the UK are rounded down to the next lower multiple of five years.

Although baptismal dates are often used to approximate birth

dates, some families waited years before baptizing children, and adult

baptisms are the norm in some religions. Both birth and marriage dates

may have been adjusted to cover for pre-wedding pregnancies.

Calendar changes must also be considered. In 1752, England and her American colonies changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. In the same year, the date the new year began was changed. Prior to 1752 it was 25 March;

this was changed to 1 January. Many other European countries had

already made the calendar changes before England had, sometimes

centuries earlier. By 1751 there was an 11-day discrepancy between the

date in England and the date in other European countries.

The French Republican Calendar

or French Revolutionary Calendar was a calendar proposed during the

French Revolution, and used by the French government for about 12 years

from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days in 1871 in Paris. Dates in

official records at this time use the revolutionary calendar and need

"translating" into the Gregorian calendar for calculating ages etc.

There are various websites which do this.

Occupations

Occupational

information may be important to understanding an ancestor's life and

for distinguishing two people with the same name. A person's occupation

may have been related to his or her social status, political interest,

and migration pattern. Since skilled trades are often passed from father

to son, occupation may also be indirect evidence of a family

relationship.

It is important to remember that a person may change occupations,

and that titles change over time as well. Some workers no longer fit

for their primary trade often took less prestigious jobs later in life,

while others moved upwards in prestige.

Many unskilled ancestors had a variety of jobs depending on the season

and local trade requirements. Census returns may contain some

embellishment; e.g., from labourer to mason, or from journeyman to master craftsman.

Names for old or unfamiliar local occupations may cause confusion if

poorly legible. For example, an ostler (a keeper of horses) and a

hostler (an innkeeper) could easily be confused for one another.

Likewise, descriptions of such occupations may also be problematic. The

perplexing description "ironer of rabbit burrows" may turn out to

describe an ironer (profession) in the Bristol

district named Rabbit Burrows. Several trades have regionally preferred

terms. For example, "shoemaker" and "cordwainer" have the same meaning.

Finally, many apparently obscure jobs are part of a larger trade

community, such as watchmaking, framework knitting or gunmaking.

Occupational data may be reported in occupational licenses, tax

assessments, membership records of professional organizations, trade

directories, census returns, and vital records (civil registration).

Occupational dictionaries are available to explain many obscure and

archaic trades.

Reliability of sources

Information

found in historical or genealogical sources can be unreliable and it is

good practice to evaluate all sources with a critical eye. Factors

influencing the reliability of genealogical information include: the

knowledge of the informant (or writer); the bias and mental state of the

informant (or write; the passage of time and the potential for copying

and compiling errors.

The quality of census data has been of special interest to historians, who have investigated reliability issues.

Knowledge of the informant

The

informant is the individual who provided the recorded information.

Genealogists must carefully consider who provided the information and

what he or she knew. In many cases the informant is identified in the

record itself. For example, a death certificate usually has two

informants: a physician who provides information about the time and

cause of death and a family member who provides the birth date, names of

parents, etc.

When the informant is not identified, one can sometimes deduce

information about the identity of the person by careful examination of

the source. One should first consider who was alive (and nearby) when

the record was created. When the informant is also the person recording

the information, the handwriting can be compared to other handwriting

samples.

When a source does not provide clues about the informant,

genealogists should treat the source with caution. These sources can be

useful if they can be compared with independent sources. For example, a

census record by itself cannot be given much weight because the

informant is unknown. However, when censuses for several years concur on

a piece of information that would not likely be guessed by a neighbor,

it is likely that the information in these censuses was provided by a

family member or other informed person. On the other hand, information

in a single census cannot be confirmed by information in an undocumented

compiled genealogy since the genealogy may have used the census record

as its source and might therefore be dependent on the same misinformed

individual.

Motivation of the informant

Even

individuals who had knowledge of the fact, sometimes intentionally or

unintentionally provided false or misleading information. A person may

have lied in order to obtain a government benefit (such as a military

pension), avoid taxation, or cover up an embarrassing situation (such as

the existence of a non-marital child). A person with a distressed state

of mind may not be able to accurately recall information. Many

genealogical records were recorded at the time of a loved one's death,

and so genealogists should consider the effect that grief may have had

on the informant of these records.

The effect of time

The

passage of time often affects a person's ability to recall information.

Therefore, as a general rule, data recorded soon after the event are

usually more reliable than data recorded many years later. However, some

types of data are more difficult to recall after many years than

others. One type especially prone to recollection errors is dates. Also

the ability to recall is affected by the significance that the event had

to the individual. These values may have been affected by cultural or

individual preferences.

Copying and compiling errors

Genealogists

must consider the effects that copying and compiling errors may have

had on the information in a source. For this reason, sources are

generally categorized in two categories: original and derivative. An

original source is one that is not based on another source. A derivative

source is information taken from another source. This distinction is

important because each time a source is copied, information about the

record may be lost and errors may result from the copyist misreading,

mistyping, or miswriting the information. Genealogists should consider

the number of times information has been copied and the types of

derivation a piece of information has undergone. The types of

derivatives include: photocopies, transcriptions, abstracts,

translations, extractions, and compilations.

In addition to copying errors, compiled sources (such as

published genealogies and online pedigree databases) are susceptible to

misidentification errors and incorrect conclusions based on

circumstantial evidence. Identity errors usually occur when two or more

individuals are assumed to be the same person. Circumstantial or

indirect evidence does not explicitly answer a genealogical question,

but either may be used with other sources to answer the question,

suggest a probable answer, or eliminate certain possibilities. Compilers

sometimes draw hasty conclusions from circumstantial evidence without

sufficiently examining all available sources, without properly

understanding the evidence, and without appropriately indicating the

level of uncertainty.

Primary and secondary sources

In

genealogical research, information can be obtained from primary or

secondary sources. Primary sources are records that were made at the

time of the event, for example a death certificate would be a primary

source for a person's death date and place. Secondary sources are

records that are made days, weeks, months, or even years after an event.

Standards and Ethics

Organizations

that educate and certify genealogists have established standards and

ethical guidelines they instruct genealogists to follow.

Research standards

Genealogy

research requires analyzing documents and drawing conclusions based on

the evidence provided in the available documents. Genealogists need

standards to determine whether or not their evaluation of the evidence

is accurate. In the past, genealogists in the United States borrowed terms from judicial law

to examine evidence found in documents and how they relate to the

researcher's conclusions. However, the differences between the two

disciplines created a need for genealogists to develop their own

standards. In 2000, the Board for Certification of Genealogists published their first manual of standards. The Genealogical Proof Standard

created by the Board for Certification of Genealogists is widely

distributed in seminars, workshops, and educational materials for

genealogists in the United States. Other genealogical organizations

around the world have created similar standards they invite genealogists

to follow. Such standards provide guidelines for genealogists to

evaluate their own research as well as the research of others.

Standards for genealogical research include:

- Clearly document and organize findings.

- Cite all sources in a specific manner so that others can locate them and properly evaluate them.

- Locate all available sources that may contain information relevant to the research question.

- Analyze findings thoroughly, without ignoring conflicts in records or negative evidence.

- Rely on original, rather than derivative sources, wherever possible.

- Use logical reasoning based on reliable sources to reach conclusions.

- Acknowledge when a specific conclusion is only "possible" or "probable" rather than "proven."

- Acknowledge that other records that have not yet been discovered may overturn a conclusion.

Ethical guidelines

Genealogists

often handle sensitive information and share and publish such

information. Because of this, there is a need for ethical standards and

boundaries for when information is too sensitive to be published.

Historically, some genealogists have fabricated information or have

otherwise been untrustworthy. Genealogical organizations around the

world have outlined ethical standards as an attempt to eliminate such

problems. Ethical standards adopted by various genealogical

organizations include:

- Respect copyright laws

- Acknowledge where one consulted another's work and do not plagiarize the work of other researchers.

- Treat original records with respect and avoid causing damage to them or removing them from repositories.

- Treat archives and archive staff with respect.

- Protect the privacy of living individuals by not publishing or otherwise disclosing information about them without their permission.

- Disclose any conflicts of interest to clients.

- When doing paid research, be clear with the client about scope of research and fees involved.

- Do not fabricate information or publish false or unproven information as proven.

- Be sensitive about information found through genealogical research that may make the client or family members uncomfortable.

In 2015, a committee presented standards for genetic genealogy

at the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy. The standards emphasize that

genealogists and testing companies should respect the privacy of clients

and recognize the limits of DNA tests. It also discusses how

genealogists should thoroughly document conclusions made using DNA

evidence.

In 2019, the Board for the Certification of Genealogists officially

updated their standards and code of ethics to include standards for

genetic genealogy.

Environmental

journalists and advocates have in recent weeks made a number of

apocalyptic predictions about the impact of climate change.

Environmental

journalists and advocates have in recent weeks made a number of

apocalyptic predictions about the impact of climate change.