Digital TV set-top box

Interactive television (also known as ITV or iTV) is a form of media convergence, adding data services to traditional television technology.

Throughout its history, these have included on-demand delivery of

content, as well as new uses such as online shopping, banking, and so

forth. Interactive TV is a concrete example of how new information

technology can be integrated vertically (into established technologies

and commercial structures) rather than laterally (creating new

production opportunities outside existing commercial structures, e.g.

the world wide web).

Definitions

Interactive television represents a continuum from low (TV on/off, volume, changing channels) to moderate interactivity (simple movies on demand without player controls) and high interactivity

in which, for example, an audience member affects the program being

watched. The most obvious example of this would be any kind of real-time

voting

on the screen, in which audience votes create decisions that are

reflected in how the show continues. A return path to the program

provider is not necessary to have an interactive program experience.

Once a movie is downloaded, for example, controls may all be local. The

link was needed to download the program, but texts and software which can be executed locally at the set-top box or IRD (Integrated Receiver Decoder) may occur automatically, once the viewer enters the channel.

History

Interactive video-on-demand (VOD) television services first appeared in the 1990s. Up until then, it was not thought possible that a television programme could be squeezed into the limited telecommunication bandwidth of a copper telephone cable to provide a VOD service of acceptable quality, as the required bandwidth of a digital television signal was around 200 Mbps, which was 2,000 times greater than the bandwidth of a speech signal over a copper telephone wire. VOD services were only made possible as a result of two major technological developments: discrete cosine transform (DCT) video compression and asymmetric digital subscriber line (ADSL) data transmission. DCT is a lossy compression technique that was first proposed by Nasir Ahmed in 1972, and was later adapted into a motion-compensated DCT algorithm for video coding standards such as the H.26x formats from 1988 onwards and the MPEG formats from 1991 onwards.

Motion-compensated DCT video compression significantly reduced the

amount of bandwidth required for a television signal, while at the same

time ADSL increased the bandwidth of data that could be sent over a

copper telephone wire. ADSL increased the bandwidth of a telephone line

from around 100 kbps to 2 Mbps, while DCT compression reduced the required bandwidth of a television signal from around 200 Mbps down to 2 Mpps. The combination of DCT and ADSL technologies made it possible to practically implement VOD services at around 2 Mbps bandwidth in the 1990s.

An interactive VOD television service was proposed as early as

1986 in Japan, where there were plans to develop an "Integrated Network

System" service. It was intended to include various interactive

services, including videophone, home shopping, tele-banking, working-at-home,

and home entertainment services. However, it was not possible to

practically implement such an interactive VOD service until the adoption

of DCT and ADSL technologies made it possible in the 1990s. In early

1994, British Telecommunications (BT) began testing an interactive VOD television trial service in the United Kingdom. It used the DCT-based MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 video compression standards, along with ADSL technology.

The first patent of interactive connected TV was registered in 1994, carried on 1995 in the United States.

It clearly exposed this new interactive technology with content feeding

and feedback through global networking. User identification allows

interacting and purchasing and some other functionalities.

Return path

The viewer must be able to alter the viewing experience (e.g. choose which angle to watch a football match), or return information to the broadcaster.

This "return path," return channel or "back channel" can be by telephone, mobile SMS (text messages), radio, digital subscriber lines (ADSL), or cable.

Cable TV

viewers receive their programs via a cable, and in the integrated cable

return path enabled platforms, they use the same cable as a return

path.

Satellite

viewers (mostly) return information to the broadcaster via their

regular telephone lines. They are charged for this service on their

regular telephone bill. An Internet connection via ADSL, or other data communications technology, is also being increasingly used.

Interactive TV can also be delivered via a terrestrial aerial (Digital Terrestrial TV such as 'Freeview' in the UK).

In this case, there is often no 'return path' as such - so data cannot

be sent back to the broadcaster (so you could not, for instance, vote on

a TV show, or order a product

sample). However, interactivity is still possible as there is still the

opportunity to interact with an application which is broadcast and

downloaded to the set-top box (so you could still choose camera angles, play games etc.).

Increasingly the return path is becoming a broadband IP

connection, and some hybrid receivers are now capable of displaying

video from either the IP connection or from traditional tuners. Some

devices are now dedicated to displaying video only from the IP channel,

which has given rise to IPTV

- Internet Protocol Television. The rise of the "broadband return path"

has given new relevance to Interactive TV, as it opens up the need to

interact with Video on Demand servers, advertisers, and website

operators.

Forms of interaction

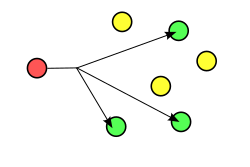

The

term "interactive television" is used to refer to a variety of rather

different kinds of interactivity (both as to usage and as to

technology), and this can lead to considerable misunderstanding. At

least three very different levels are important (see also the

instructional video literature which has described levels of

interactivity in computer-based instruction which will look very much

like tomorrow's interactive television):

Interactivity with a TV set

The simplest, Interactivity with a TV set

is already very common, starting with the use of the remote control to

enable channel surfing behaviors, and evolving to include video-on-demand, VCR-like pause, rewind, and fast forward, and DVRs,

commercial skipping and the like. It does not change any content or its

inherent linearity, only how users control the viewing of that content.

DVRs allow users to time shift content in a way that is impractical

with VHS. Though this form of interactive TV is not insignificant,

critics claim that saying that using a remote control to turn TV sets on

and off makes television interactive is like saying turning the pages

of a book makes the book interactive.

In the not too distant future, the questioning of what is real

interaction with the TV will be difficult. Panasonic already has face

recognition technology implemented its prototype Panasonic Life Wall.

The Life Wall is literally a wall in your house that doubles as a

screen. Panasonic uses their face recognition technology to follow the

viewer around the room, adjusting its screen size according to the

viewers distance from the wall. Its goal is to give the viewer the best

seat in the house, regardless of location. The concept was released at

Panasonic Consumer Electronics Show in 2008. Its anticipated release

date is unknown, but it can be assumed technology like this will not

remain hidden for long.

Interactivity with TV program content

In its deepest sense, Interactivity with normal TV program content

is the one that is "interactive TV", but it is also the most

challenging to produce. This is the idea that the program, itself, might

change based on viewer input. Advanced forms, which still have

uncertain prospect for becoming mainstream, include dramas where viewers

get to choose or influence plot details and endings.

- As an example, in Accidental Lovers viewers can send mobile text messages to the broadcast and the plot transforms on the basis of the keywords picked from the messages.

- Global Television Network offers a multi-monitor interactive game for Big Brother 8 (US) "'In The House'" which allows viewers to predict who will win each competition, who's going home, as well as answering trivia questions and instant recall challenges throughout the live show. Viewers login to the Global website to play, with no downloads required.

- Another kind of example of interactive content is the Hugo game on Television where viewers called the production studio, and were allowed to control the game character in real time using telephone buttons by studio personnel, similar to The Price Is Right.

- Another example is the Clickvision Interactive Perception Panel used on news programmes in Britain, a kind of instant clap-o-meter run over the telephone.

Simpler forms, which are enjoying some success, include programs that

directly incorporate polls, questions, comments, and other forms of

(virtual) audience response back into the show. One example would be

Australian media producer Yahoo!7's

Fango mobile app, which allows viewers to access program-related polls,

discussion groups and (in some cases) input into live programming.

During the 2012 Australian Open viewers used the app to suggest questions for commentator Jim Courier to ask players in post-match interviews.

There is much debate as to how effective and popular this kind of

truly interactive TV can be. It seems likely that some forms of it will

be popular, but that viewing of pre-defined content, with a scripted

narrative arc, will remain a major part of the TV experience

indefinitely. The United States lags far behind the rest of the

developed world in its deployment of interactive television. This is a

direct response to the fact that commercial television in the U.S. is

not controlled by the government, whereas the vast majority of other

countries' television systems are controlled by the government. These

"centrally planned" television systems are made interactive by fiat,

whereas in the U.S., only some members of the Public Broadcasting System

has this capability.

Commercial broadcasters and other content providers serving the US market are constrained from adopting advanced interactive technologies

because they must serve the desires of their customers, earn a level of

return on investment for their investors, and are dependent on the

penetration of interactive technology into viewers' homes. In

association with many factors such as

- requirements for backward compatibility of TV content formats, form factors and Customer Premises Equipment (CPE)

- the 'cable monopoly' laws that are in force in many communities served by cable TV operators

- consumer acceptance of the pricing structure for new TV-delivered services. Over the air (broadcast) TV is Free in the US, free of taxes or usage fees.

- proprietary coding of set top boxes by cable operators and box manufacturers

- the ability to implement 'return path' interaction in rural areas that have low, or no technology infrastructure

- the competition from Internet-based content and service providers for the consumers' attention and budget

- and many other technical and business roadblocks

The least understood, Interactivity with TV-related content

may have most promise to alter how we watch TV over the next decade.

Examples include getting more information about what is on the TV,

weather, sports, movies, news, or the like.

Similar (and most likely to pay the bills), getting more

information about what is being advertised, and the ability to buy

it—(after futuristic innovators make it) is called "tcommerce" (short for "television commerce").

Partial steps in this direction are already becoming a mass phenomenon,

as Web sites and mobile phone services coordinate with TV programs

(note: this type of interactive TV is currently being called

"participation TV" and GSN and TBS are proponents of it). This kind of

multitasking is already happening on large scale—but there is currently

little or no automated support for relating that secondary interaction

to what is on the TV compared to other forms of interactive TV. Others

argue that this is more a "web-enhanced" television viewing than

interactive TV. In the coming months and years, there will be no need to

have both a computer and a TV set for interactive television as the

interactive content will be built into the system via the next

generation of set-top boxes. However, set-top-boxes have yet to get a

strong foothold in American households as price (pay per service pricing

model) and lack of interactive content have failed to justify their

cost.

One individual who is working to radically disrupt this field is

Michael McCarty, who is the Founder and CEO of a new wave of interactive

TV products that will be hitting the market in early 2013. As he

suggested in his presentation to the "Community for Interactive Media",

"Static media is on its way out, and if Networks would like to stay in

the game, they must adapt to consumers needs."

Many think of interactive TV primarily in terms of "one-screen"

forms that involve interaction on the TV screen, using the remote

control, but there is another significant form of interactive TV that

makes use of Two-Screen Solutions, such as NanoGaming. In this case, the second screen

is typically a PC (personal computer) connected to a Web site

application. Web applications may be synchronized with the TV broadcast,

or be regular websites that provide supplementary content to the live

broadcast, either in the form of information, or as interactive game or

program. Some two-screen applications allow for interaction from a

mobile device (phone or PDA), that run "in synch" with the show.

Such services are sometimes called "Enhanced TV," but this

term is in decline, being seen as anachronistic and misused

occasionally. (Note: "Enhanced TV" originated in the mid-late 1990s as a

term that some hoped would replace the umbrella term of "interactive

TV" due to the negative associations "interactive TV" carried because of

the way companies and the news media over-hyped its potential in the

early 1990s.)

Notable Two-Screen Solutions have been offered for specific popular programs by many US broadcast TV networks. Today, two-screen interactive TV is called either 2-screen (for short) or "Synchronized TV"

and is widely deployed around the US by national broadcasters with the

help of technology offerings from certain companies. The first such

application was Chat Television™ (ChatTV.com), originally developed in

1996. The system synchronized online services with television

broadcasts, grouping users by time-zone and program so that all

real-time viewers could participate in a chat or interactive gathering

during the show's airing.

One-screen interactive TV generally requires special support in the set-top box, but Two-Screen Solutions, synchronized interactive TV applications generally do not, relying instead on Internet

or mobile phone servers to coordinate with the TV and are most often

free to the user. Developments from 2006 onwards indicate that the

mobile phone can be used for seamless authentication through Bluetooth, explicit authentication through near-field communication. Through such an authentication it will be possible to provide personalized services to the mobile phone.

Interactive TV services

Notable interactive TV services are:

- ActiveVideo (formerly known as ICTV) - Pioneers in interactive TV and creators of CloudTV™: A cloud-based interactive TV platform built on current web and television standards. The network-centric approach provides for the bulk of application and video processing to be done in the cloud, and delivers a standard MPEG stream to virtually any digital set-top box, web-connected TV or media device.

- T-commerce - Is a commerce transaction through the set top box return path connection.

- BBC Red Button

- ATVEF - 'Advanced Television Enhancement Forum' is a group of companies that are set up to create HTML based TV products and services. ATVEF's work has resulted in an Enhanced Content Specification which makes it possible for developers to create their content once and have it display properly on any compliant receiver.

- MSN TV - A former service originally introduced as WebTV. It supplied computerless Internet access. It required a set-top box that sold for $100 to $200, with a monthly access fee. The service was discontinued in 2013, although customer service remained available until 2014.

- Philips Net TV - solution to view Internet content designed for TV; directly integrated inside the TV set. No extra subscription costs or hardware costs involved.

- An Interactive TV purchasing system was introduced in 1994 in France. The system was using a regular TV set connected together with a regular antenna and the Internet for feedback. A demo has shown the possibility of immediate purchasing, interactively with displayed contents.

- QUBE - A very early example of this concept, it was introduced experimentally by Warner Cable (later Time Warner Cable, now part of Charter Spectrum) in Columbus, Ohio in 1977. Its most notable feature was five buttons that could allow the viewers to, among other things, participate in interactive game shows, and answer survey questions. While successful, going on to expand to a few other cities, the service eventually proved to be too expensive to run, and was discontinued by 1984, although the special boxes would continue to be serviced well into the 1990s.

Closed-circuit Interactive television

Television sets can also be used as computer displays or for video games.

User interaction

Interactive TV has been described in human-computer interaction research as "lean back" interaction,

as users are typically relaxing in the living room environment with a

remote control in one hand. This is a very simplistic definition of

interactive television that is less and less descriptive of interactive

television services that are in various stages of market introduction.

This is in contrast to the descriptor of personal computer-oriented "lean forward" experience of a keyboard, mouse and monitor.

This description is becoming more distracting than useful as video game

users, for example, don't lean forward while they are playing video

games on their television sets, a precursor to interactive TV. A more

useful mechanism for categorizing the differences between PC- and

TV-based user interaction is by measuring the distance the user is from

the Device. Typically a TV viewer is "leaning back" in their sofa, using

only a Remote Control as a means of interaction. While a PC user is

2 ft or 3 ft (60 or 100 cm) from his high resolution screen using a

mouse and keyboard. The demands of distance, and user input devices,

requires the application's look and feel to be designed differently.

Thus Interactive TV applications are often designed for the "10-foot user interface"

while PC applications and web pages are designed for the "3ft user

experience". This style of interface design rather than the "lean back

or lean forward" model is what truly distinguishes Interactive TV from

the web or PC.

However even this mechanism is changing because there is at least one

web-based service which allows you to watch internet television on a PC

with a wireless remote control.

In the case of Two-Screen Solutions Interactive TV, the

distinctions of "lean-back" and "lean-forward" interaction become more

and more indistinguishable. There has been a growing proclivity to media multitasking,

in which multiple media devices are used simultaneously (especially

among younger viewers). This has increased interest in two-screen

services, and is creating a new level of multitasking in interactive TV.

In addition, video is now ubiquitous on the web, so research can now be

done to see if there is anything left to the notion of "lean back"

"versus" "lean forward" uses of interactive television.

For one-screen services, interactivity is supplied by the manipulation of the API of the particular software installed on a set-top box, referred to as 'middleware'

due to its intermediary position in the operating environment. Software

programs are broadcast to the set-top box in a 'carousel'.

On UK DTT (Freeview uses ETSI based MHEG-5), and Sky's DTH platform uses ETSI based WTVML in DVB-MHP systems and for OCAP; this is a DSM-CC Object Carousel.

The set-top box can then load and execute the application. In the

UK this is typically done by a viewer pressing a "trigger" button on

their remote control (e.g. the red button, as in "press red").

Interactive TV Sites

have the requirement to deliver interactivity directly from internet

servers, and therefore need the set-top box's middleware to support some

sort of TV Browser, content translation system or content rendering

system. Middleware examples like Liberate are based on a version of HTML/JavaScript and have rendering capabilities built in, while others such as OpenTV and DVB-MHP can load microbrowsers and applications to deliver content from TV Sites. In October 2008, the ITU's J.201 paper on interoperability of TV Sites recommended authoring using ETSI WTVML to achieve interoperability by allowing dynamic TV Site to be automatically translated into various TV dialects of HTML/JavaScript, while maintaining compatibility with middlewares such as MHP and OpenTV via native WTVML microbrowsers.

Typically the distribution system for Standard Definition digital TV is based on the MPEG-2 specification, while High Definition distribution is likely to be based on the MPEG-4

meaning that the delivery of HD often requires a new device or set-top

box, which typically are then also able to decode Internet Video via

broadband return paths.

Emergent approaches such as the Fango app

have utilised mobile apps on smartphones and tablet devices to present

viewers with a hybrid experience across multiple devices, rather than

requiring dedicated hardware support.

Interactive television projects

Some

interactive television projects are consumer electronics boxes which

provide set-top interactivity, while other projects are supplied by the

cable television companies (or multiple system operator, or MSO) as a

system-wide solution. Even other, newer, approaches integrate the

interactive functionality in the TV, thus negating the need for a

separate box. Some examples of interactive television include:

- MSOs

- Cox Communications (US)

- Time Warner (US)

- Comcast (US)

- Cablevision (US)

- Previous MSO trials or demos

- Tele-TV from Bell Atlantic, NYNEX, Pacific Telesis, Creative Artists Agency (US) - no longer in operation

- Full Service Network from Time Warner (US) - no longer in operation

- GTE mainStreet (US) a former product of GTE, also provided over select Continental Cablevision and Daniels cable television systems.

- Smartbox from TV Cabo, Novabase and Microsoft (PT) - this no longer in operation, although some of the equipment is still used for the digital TV service. This was the pioneer project.

- Consumer electronics solutions

- TiVo

- ReplayTV

- UltimateTV

- Miniweb Interactive

- Microsoft Windows XP Media Center

- Philips Net TV

- Two-Screen Solutions, or "enhanced TV" solutions

- See Enhanced TV

- Chat Television (IBSC), purchased by Charter Communications, Inc. in May 2001.

- Hospitality & healthcare solutions

- Sonifi Solutions (formerly LodgeNet)

Mobile phone interaction with the STB and the TV:

- ITEA WellCom Project using Bluetooth and NFC for authentication, pairing, and seamless service access

Interactive Video and Data Services

IVDS is a wireless implementation of interactive TV, it utilizes part of the VHF TV frequency spectrum (218–219 MHz).