Immunization against diseases is a key preventive healthcare measure.

Preventive healthcare (alternatively preventative healthcare or prophylaxis) consists of measures taken for disease prevention. Disease and disability are affected by environmental factors, genetic predisposition,

disease agents, and lifestyle choices and are dynamic processes which

begin before individuals realize they are affected. Disease prevention

relies on anticipatory actions that can be categorized as primal, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention.

Each year, millions of people die of preventable deaths. A 2004

study showed that about half of all deaths in the United States in 2000

were due to preventable behaviors and exposures. Leading causes included cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, unintentional injuries, diabetes, and certain infectious diseases. This same study estimates that 400,000 people die each year in the United States due to poor diet and a sedentary lifestyle. According to estimates made by the World Health Organization (WHO), about 55 million people died worldwide in 2011, two thirds of this group from non-communicable diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and chronic cardiovascular and lung diseases. This is an increase from the year 2000, during which 60% of deaths were attributed to these diseases.

Preventive healthcare is especially important given the worldwide rise

in prevalence of chronic diseases and deaths from these diseases.

There are many methods for prevention of disease. One of them is prevention of teenage smoking through information giving.

It is recommended that adults and children aim to visit their doctor

for regular check-ups, even if they feel healthy, to perform disease screening,

identify risk factors for disease, discuss tips for a healthy and

balanced lifestyle, stay up to date with immunizations and boosters, and

maintain a good relationship with a healthcare provider. Some common disease screenings include checking for hypertension (high blood pressure), hyperglycemia (high blood sugar, a risk factor for diabetes mellitus), hypercholesterolemia (high blood cholesterol), screening for colon cancer, depression, HIV and other common types of sexually transmitted disease such as chlamydia, syphilis, and gonorrhea, mammography (to screen for breast cancer), colorectal cancer screening, a Pap test (to check for cervical cancer), and screening for osteoporosis. Genetic testing can also be performed to screen for mutations that cause genetic disorders or predisposition to certain diseases such as breast or ovarian cancer.

However, these measures are not affordable for every individual and the

cost effectiveness of preventive healthcare is still a topic of debate.

Levels of prevention

Preventive healthcare strategies are described as taking place at the primal, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention levels.

Although advocated as preventive medicine in the early twentieth century by Sara Josephine Baker,

in the 1940s, Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark coined the term

primary prevention. They worked at the Harvard and Columbia University

Schools of Public Health, respectively, and later expanded the levels to

include secondary and tertiary prevention. Goldston (1987) notes that

these levels might be better described as "prevention, treatment, and

rehabilitation", although the terms primary, secondary, and tertiary

prevention are still in use today. The concept of primal prevention has

been created much more recently, in relation to the new developments in

molecular biology over the last fifty years,

more particularly in epigenetics, which point to the paramount

importance of environmental conditions - both physical and affective -

on the organism during its fetal and newborn life (or so-called primal

period of life).

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| Primal and primordial prevention | Any measure aimed at helping future parents provide their upcoming

child with adequate attention, as well as secure physical and affective

environments from conception to first birthday.

Primordial prevention refers to measures designed to avoid the development of risk factors in the first place, early in life.

|

| Primary prevention | Methods to avoid occurrence of disease either through eliminating disease agents or increasing resistance to disease. Examples include immunization against disease, maintaining a healthy diet and exercise regimen, and avoiding smoking. |

| Secondary prevention | Methods to detect and address an existing disease prior to the appearance of symptoms. Examples include treatment of hypertension (a risk factor for many cardiovascular diseases), and cancer screenings. |

| Tertiary prevention | Methods to reduce the harm of symptomatic disease, such as disability or death, through rehabilitation and treatment. Examples include surgical procedures that halt the spread or progression of disease. |

| Quaternary prevention | Methods to mitigate or avoid results of unnecessary or excessive interventions in the health system |

Primal and primordial prevention

Primal prevention has recently been propounded as a separate category of "health promotion". This health promotion par excellence

is based on the 'new knowledge' in molecular biology, in particular on

epigenetic knowledge, which points to how much affective - as well as

physical - environment during fetal and newborn life may determine each

and every aspect of adult health. This new way of promoting health consists mainly in providing future parents with pertinent, unbiased information on primal health and supporting them during their child's primal period of life

(i.e., "from conception to first anniversary" according to definition

by the Primal Health Research Centre, London). This includes adequate

parental leave - ideally for both parents - with kin caregiving and financial help where needed.

Another related concept is primordial prevention which refers to

all measures designed to prevent the development of risk factors in the

first place, early in life.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention consists of traditional "health promotion" and "specific protection."

Health promotion activities are current, non-clinical life choices. For

example, eating nutritious meals and exercising daily, that both

prevent disease and create a sense of overall well-being. Preventing

disease and creating overall well-being, prolongs our life expectancy.

Health-promotional activities do not target a specific disease or

condition but rather promote health and well-being on a very general

level. On the other hand, specific protection targets a type or group of diseases and complements the goals of health promotion.

Food is very much the most basic tool in preventive health care.

The 2011 National Health Interview Survey performed by the Centers for

Disease Control was the first national survey to include questions about

ability to pay for food. Difficulty with paying for food, medicine, or

both is a problem facing 1 out of 3 Americans. If better food options

were available through food banks, soup kitchens, and other resources

for low-income people, obesity and the chronic conditions that come

along with it would be better controlled.

A "food desert" is an area with restricted access to healthy foods due

to a lack of supermarkets within a reasonable distance. These are often

low-income neighborhoods with the majority of residents lacking

transportation.

There have been several grassroots movements in the past 20 years to

encourage urban gardening, such as the GreenThumb organization in New

York City. Urban gardening uses vacant lots to grow food for a

neighborhood and is cultivated by the local residents.

Mobile fresh markets are another resource for residents in a "food

desert", which are specially outfitted buses bringing affordable fresh

fruits and vegetables to low-income neighborhoods. These programs often

hold educational events as well such as cooking and nutrition guidance. Programs such as these are helping to provide healthy, affordable foods to people who need them.

Scientific advancements in genetics have significantly

contributed to the knowledge of hereditary diseases and have facilitated

great progress in specific protective measures in individuals who are

carriers of a disease gene or have an increased predisposition to a

specific disease. Genetic testing has allowed physicians to make quicker

and more accurate diagnoses and has allowed for tailored treatments or personalized medicine.

Similarly, specific protective measures such as water purification,

sewage treatment, and the development of personal hygienic routines

(such as regular hand-washing) became mainstream upon the discovery of

infectious disease agents such as bacteria. These discoveries have been

instrumental in decreasing the rates of communicable diseases that are

often spread in unsanitary conditions. Preventing sexually transmitted infections is another form of primary prevention.

Secondary prevention

Secondary

prevention deals with latent diseases and attempts to prevent an

asymptomatic disease from progressing to symptomatic disease.

Certain diseases can be classified as primary or secondary. This

depends on definitions of what constitutes a disease, though, in

general, primary prevention addresses the root cause of a disease or

injury whereas secondary prevention aims to detect and treat a disease early on.

Secondary prevention consists of "early diagnosis and prompt treatment"

to contain the disease and prevent its spread to other individuals, and

"disability limitation" to prevent potential future complications and

disabilities from the disease.

For example, early diagnosis and prompt treatment for a syphilis

patient would include a course of antibiotics to destroy the pathogen

and screening and treatment of any infants born to syphilitic mothers.

Disability limitation for syphilitic patients includes continued

check-ups on the heart, cerebrospinal fluid, and central nervous system

of patients to curb any damaging effects such as blindness or paralysis.

Tertiary prevention

Finally,

tertiary prevention attempts to reduce the damage caused by symptomatic

disease by focusing on mental, physical, and social rehabilitation.

Unlike secondary prevention, which aims to prevent disability, the

objective of tertiary prevention is to maximize the remaining

capabilities and functions of an already disabled patient.

Goals of tertiary prevention include: preventing pain and damage,

halting progression and complications from disease, and restoring the

health and functions of the individuals affected by disease.

For syphilitic patients, rehabilitation includes measures to prevent

complete disability from the disease, such as implementing work-place

adjustments for the blind and paralyzed or providing counseling to

restore normal daily functions to the greatest extent possible.

Leading causes of preventable death

United States

The

leading cause of death in the United States was tobacco. However, poor

diet and lack of exercise may soon surpass tobacco as a leading cause of

death. These behaviors are modifiable and public health and prevention

efforts could make a difference to reduce these deaths.

| Cause | Deaths caused | % of all deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco smoking | 435,000 | 18.1 |

| Poor diet and physical inactivity | 400,000 | 16.6 |

| Alcohol consumption | 85,000 | 3.5 |

| Infectious diseases | 75,000 | 3.1 |

| Toxicants | 55,000 | 2.3 |

| Traffic collisions | 43,000 | 1.8 |

| Firearm incidents | 29,000 | 1.2 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 20,000 | 0.8 |

| Drug abuse | 17,000 | 0.7 |

Worldwide

The leading causes of preventable death worldwide share similar trends to the United States.

There are a few differences between the two, such as malnutrition,

pollution, and unsafe sanitation, that reflect health disparities

between the developing and developed world.

| Cause | Deaths caused (millions per year) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 7.8 |

| Smoking | 5.0 |

| High cholesterol | 3.9 |

| Malnutrition | 3.8 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 3.0 |

| Poor diet | 2.8 |

| Overweight and obesity | 2.5 |

| Physical inactivity | 2.0 |

| Alcohol | 1.9 |

| Indoor air pollution from solid fuels | 1.8 |

| Unsafe water and poor sanitation | 1.6 |

Child mortality

In 2010, 7.6 million children died before reaching the age of 5. While this is a decrease from 9.6 million in the year 2000, it is still far from the fourth Millennium Development Goal to decrease child mortality by two-thirds by the year 2015. Of these deaths, about 64% were due to infection (including diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria). About 40% of these deaths occurred in neonates (children ages 1–28 days) due to pre-term birth complications. The highest number of child deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia. In Africa, almost no progress has been made in reducing neonatal death since 1990.

India, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, and China

contributed to almost 50% of global child deaths in 2010. Targeting

efforts in these countries is essential to reducing the global child

death rate.

Child mortality is caused by a variety of factors including poverty, environmental hazards, and lack of maternal education.

The World Health Organization created a list of interventions in the

following table that were judged economically and operationally

"feasible," based on the healthcare resources and infrastructure in 42

nations that contribute to 90% of all infant and child deaths. The table

indicates how many infant and child deaths could have been prevented in

the year 2000, assuming universal healthcare coverage.

| Intervention | Percent of all child deaths preventable |

|---|---|

| Breastfeeding | 13 |

| Insecticide-treated materials | 7 |

| Complementary feeding | 6 |

| Zinc | 4 |

| Clean delivery | 4 |

| Hib vaccine | 4 |

| Water, sanitation, hygiene | 3 |

| Antenatal steroids | 3 |

| Newborn temperature management | 2 |

| Vitamin A | 2 |

| Tetanus toxoid | 2 |

| Nevirapine and replacement feeding | 2 |

| Antibiotics for premature rupture of membranes | 1 |

| Measles vaccine | 1 |

| Antimalarial intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy | <1 font=""> |

Preventive methods

Obesity

Obesity

is a major risk factor for a wide variety of conditions including

cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, certain cancers, and type 2

diabetes. In order to prevent obesity, it is recommended that

individuals adhere to a consistent exercise regimen as well as a

nutritious and balanced diet. A healthy individual should aim for

acquiring 10% of their energy from proteins, 15-20% from fat, and over

50% from complex carbohydrates, while avoiding alcohol as well as foods

high in fat, salt, and sugar.

Sedentary adults should aim for at least half an hour of moderate-level

daily physical activity and eventually increase to include at least 20

minutes of intense exercise, three times a week.

Preventive health care offers many benefits to those that chose to

participate in taking an active role in the culture. The medical system

in our society is geared toward curing acute symptoms of disease after

the fact that they have brought us into the emergency room. An ongoing

epidemic within American culture is the prevalence of obesity. Eating

healthier and routinely exercising plays a huge role in reducing an

individual's risk for type 2 diabetes. About 23.6 million people in the

United States have diabetes. Of those, 17.9 million are diagnosed and

5.7 million are undiagnosed. Ninety to 95 percent of people with

diabetes have type 2 diabetes. Diabetes is the main cause of kidney

failure, limb amputation, and new-onset blindness in American adults.

Sexually transmitted infections

U.S. propaganda poster Fool the Axis Use Prophylaxis, 1942

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as syphilis and HIV, are common but preventable with safe-sex practices. STIs can be asymptomatic, or cause a range of symptoms. Preventive measures for STIs are called prophylactics. The term especially applies to the use of condoms, which are highly effective at preventing disease, but also to other devices meant to prevent STIs, such as dental dams and latex gloves. Other means for preventing STIs include education on how to use condoms or other such barrier devices, testing partners

before having unprotected sex, receiving regular STI screenings, to

both receive treatment and prevent spreading STIs to partners, and,

specifically for HIV, regularly taking prophylactic antiretroviral

drugs, such as Truvada. Post-exposure prophylaxis,

started within 72 hours (optimally less than 1 hour) after exposure to

high-risk fluids, can also protect against HIV transmission.

Malaria prevention using genetic modification

Genetically modified mosquitoes are being used in developing countries to control malaria. This approach has been subject to objections and controversy.

Thrombosis

Thrombosis

is a serious circulatory disease affecting thousands, usually older

persons undergoing surgical procedures, women taking oral contraceptives

and travelers. Consequences of thrombosis can be heart attacks and

strokes. Prevention can include: exercise, anti-embolism stockings,

pneumatic devices, and pharmacological treatments.

Cancer

In recent years, cancer

has become a global problem. Low and middle income countries share a

majority of the cancer burden largely due to exposure to carcinogens

resulting from industrialization and globalization.

However, primary prevention of cancer and knowledge of cancer risk

factors can reduce over one third of all cancer cases. Primary

prevention of cancer can also prevent other diseases, both communicable

and non-communicable, that share common risk factors with cancer.

Lung cancer

Distribution of lung cancer in the United States

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and Europe and is a major cause of death in other countries. Tobacco is an environmental carcinogen and the major underlying cause of lung cancer.

Between 25% and 40% of all cancer deaths and about 90% of lung cancer

cases are associated with tobacco use. Other carcinogens include

asbestos and radioactive materials. Both smoking and second-hand exposure from other smokers can lead to lung cancer and eventually death. Therefore, prevention of tobacco use is paramount to prevention of lung cancer.

Individual, community, and statewide interventions can prevent or

cease tobacco use. 90% of adults in the US who have ever smoked did so

prior to the age of 20. In-school prevention/educational programs, as

well as counseling resources, can help prevent and cease adolescent

smoking. Other cessation techniques include group support programs, nicotine replacement therapy

(NRT), hypnosis, and self-motivated behavioral change. Studies have

shown long term success rates (>1 year) of 20% for hypnosis and

10%-20% for group therapy.

Cancer screening

programs serve as effective sources of secondary prevention. The Mayo

Clinic, Johns Hopkins, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering hospitals conducted

annual x-ray screenings and sputum cytology tests and found that lung

cancer was detected at higher rates, earlier stages, and had more

favorable treatment outcomes, which supports widespread investment in

such programs.

Legislation can also affect smoking prevention and cessation. In

1992, Massachusetts (United States) voters passed a bill adding an extra

25 cent tax to each pack of cigarettes, despite intense lobbying and

$7.3 million spent by the tobacco industry to oppose this bill. Tax

revenue goes toward tobacco education and control programs and has led

to a decline of tobacco use in the state.

Lung cancer and tobacco smoking are increasing worldwide,

especially in China. China is responsible for about one-third of the

global consumption and production of tobacco products.

Tobacco control policies have been ineffective as China is home to 350

million regular smokers and 750 million passive smokers and the annual

death toll is over 1 million.

Recommended actions to reduce tobacco use include: decreasing tobacco

supply, increasing tobacco taxes, widespread educational campaigns,

decreasing advertising from the tobacco industry, and increasing tobacco

cessation support resources.

In Wuhan, China, a 1998 school-based program implemented an

anti-tobacco curriculum for adolescents and reduced the number of

regular smokers, though it did not significantly decrease the number of

adolescents who initiated smoking. This program was therefore effective

in secondary but not primary prevention and shows that school-based

programs have the potential to reduce tobacco use.

Skin cancer

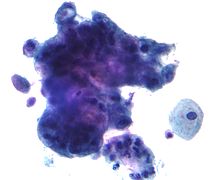

An image of melanoma, one of the deadliest forms of skin cancer

Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States. The most lethal form of skin cancer, melanoma, leads to over 50,000 annual deaths in the United States.

Childhood prevention is particularly important because a significant

portion of ultraviolet radiation exposure from the sun occurs during

childhood and adolescence and can subsequently lead to skin cancer in

adulthood. Furthermore, childhood prevention can lead to the development

of healthy habits that continue to prevent cancer for a lifetime.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) recommends several primary prevention methods including: limiting

sun exposure between 10 AM and 4 PM, when the sun is strongest, wearing

tighter-weave natural cotton clothing, wide-brim hats, and sunglasses

as protective covers, using sunscreens that protect against both UV-A

and UV-B rays, and avoiding tanning salons.

Sunscreen should be reapplied after sweating, exposure to water

(through swimming for example) or after several hours of sun exposure.

Since skin cancer is very preventable, the CDC recommends school-level

prevention programs including preventive curricula, family involvement,

participation and support from the school's health services, and

partnership with community, state, and national agencies and

organizations to keep children away from excessive UV radiation

exposure.

Most skin cancer and sun protection data comes from Australia and the United States.

An international study reported that Australians tended to demonstrate

higher knowledge of sun protection and skin cancer knowledge, compared

to other countries.

Of children, adolescents, and adults, sunscreen was the most commonly

used skin protection. However, many adolescents purposely used sunscreen

with a low sun protection factor (SPF) in order to get a tan.

Various Australian studies have shown that many adults failed to use

sunscreen correctly; many applied sunscreen well after their initial sun

exposure and/or failed to reapply when necessary.

A 2002 case-control study in Brazil showed that only 3% of case

participants and 11% of control participants used sunscreen with SPF

>15.

Cervical cancer

The presence of cancer (adenocarcinoma) detected on a Pap test

Cervical cancer ranks among the top three most common cancers among women in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Asia.

Cervical cytology screening aims to detect abnormal lesions in the

cervix so that women can undergo treatment prior to the development of

cancer. Given that high quality screening and follow-up care has been

shown to reduce cervical cancer rates by up to 80%, most developed

countries now encourage sexually active women to undergo a Pap test

every 3–5 years. Finland and Iceland have developed effective organized

programs with routine monitoring and have managed to significantly

reduce cervical cancer mortality while using fewer resources than

unorganized, opportunistic programs such as those in the United States

or Canada.

In developing nations in Latin America, such as Chile, Colombia,

Costa Rica, and Cuba, both public and privately organized programs have

offered women routine cytological screening since the 1970s. However,

these efforts have not resulted in a significant change in cervical

cancer incidence or mortality in these nations. This is likely due to

low quality, inefficient testing. However, Puerto Rico, which has

offered early screening since the 1960s, has witnessed almost a 50%

decline in cervical cancer incidence and almost a four-fold decrease in

mortality between 1950 and 1990.

Brazil, Peru, India, and several high-risk nations in sub-Saharan Africa

which lack organized screening programs, have a high incidence of

cervical cancer.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is globally the second most common cancer in women and the third-most common in men, and the fourth most common cause of cancer death after lung, stomach, and liver cancer, having caused 715,000 deaths in 2010.

It is also highly preventable; about 80 percent of colorectal cancers begin as benign growths, commonly called polyps, which can be easily detected and removed during a colonoscopy. Other methods of screening for polyps and cancers include fecal occult blood

testing. Lifestyle changes that may reduce the risk of colorectal

cancer include increasing consumption of whole grains, fruits and

vegetables, and reducing consumption of red meat.

Health disparities and barriers to accessing care

Access

to healthcare and preventive health services is unequal, as is the

quality of care received. A study conducted by the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality (AHRQ) revealed health disparities

in the United States. In the United States, elderly adults (>65

years old) received worse care and had less access to care than their

younger counterparts. The same trends are seen when comparing all racial

minorities (black, Hispanic, Asian) to white patients, and low-income

people to high-income people.

Common barriers to accessing and utilizing healthcare resources

included lack of income and education, language barriers, and lack of

health insurance. Minorities were less likely than whites to possess

health insurance, as were individuals who completed less education.

These disparities made it more difficult for the disadvantaged groups to

have regular access to a primary care provider, receive immunizations,

or receive other types of medical care.

Additionally, uninsured people tend to not seek care until their

diseases progress to chronic and serious states and they are also more

likely to forgo necessary tests, treatments, and filling prescription

medications.

These sorts of disparities and barriers exist worldwide as well.

Often, there are decades of gaps in life expectancy between developing

and developed countries. For example, Japan has an average life

expectancy that is 36 years greater than that in Malawi.

Low-income countries also tend to have fewer physicians than

high-income countries. In Nigeria and Myanmar, there are fewer than 4

physicians per 100,000 people while Norway and Switzerland have a ratio

that is ten-fold higher.

Common barriers worldwide include lack of availability of health

services and healthcare providers in the region, great physical distance

between the home and health service facilities, high transportation

costs, high treatment costs, and social norms and stigma toward

accessing certain health services.

Economics of lifestyle-based prevention

With

lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise rising to the top of

preventable death statistics, the economics of healthy lifestyle is a

growing concern. There is little question that positive lifestyle

choices provide an investment in health throughout life. To gauge success, traditional measures such as the quality years of life method (QALY), show great value. However, that method does not account for the cost of chronic conditions or future lost earnings because of poor health.[65]

Developing future economic models that would guide both private and

public investments as well as drive future policy to evaluate the

efficacy of positive lifestyle choices on health is a major topic for

economists globally.

Americans spend over three trillion a year on health care but have a higher rate of infant mortality, shorter life expectancies, and a higher rate of diabetes than other high-income nations because of negative lifestyle choices. Despite these large costs, very little is spent on prevention for lifestyle-caused conditions in comparison. The Journal of the American Medical Association estimates that $101 billion was spent in 2013 on the preventable disease of diabetes, and another $88 billion was spent on heart disease.

In an effort to encourage healthy lifestyle choices, workplace

wellness programs are on the rise; but the economics and effectiveness

data are still continuing to evolve and develop.

Health insurance coverage impacts lifestyle choices. In a study

by Sudano and Baker, even intermittent loss of coverage has negative

effects on healthy choices. The potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act

(ACA) could significantly impact coverage for many Americans, as well

as “The Prevention and Public Health Fund” which is our nation's first

and only mandatory funding stream dedicated to improving the public's

health.

Also covered in the ACA is counseling on lifestyle prevention issues,

such as weight management, alcohol use, and treatment for depression. Policy makers can have substantial effects on the lifestyle choices made by Americans.

Because chronic illnesses predominate as a cause of death in the US and pathways for treating chronic illnesses are complex and multifaceted, prevention is a best practice approach to chronic disease when possible. In many cases, prevention requires mapping complex pathways to determine the ideal point for intervention. Cost-effectiveness

of prevention is achievable, but impacted by the length of time it

takes to see effects/outcomes of intervention. This makes prevention

efforts difficult to fund—particularly in strained financial contexts.

Prevention potentially creates other costs as well, due to extending the

lifespan and thereby increasing opportunities for illness. In order to

assess the cost-effectiveness of prevention, the cost of the preventive

measure, savings from avoiding morbidity, and the cost from extending

the lifespan need to be considered. Life extension costs become smaller when accounting for savings from postponing the last year of life, which makes up a large fraction of lifetime medical expenditures and becomes cheaper with age.

Prevention leads to savings only if the cost of the preventive measure

is less than the savings from avoiding morbidity net of the cost of

extending the life span. In order to establish reliable economics of

prevention

for illnesses that are complicated in origin, knowing how best to

assess prevention efforts, i.e. developing useful measures and

appropriate scope, is required.

Effectiveness

Overview

There is no general consensus as to whether or not preventive healthcare measures are cost-effective, but they increase the quality of life

dramatically. There are varying views on what constitutes a "good

investment." Some argue that preventive health measures should save more

money than they cost, when factoring in treatment costs in the absence

of such measures. Others argue in favor of "good value" or conferring

significant health benefits even if the measures do not save money.

Furthermore, preventive health services are often described as one

entity though they comprise a myriad of different services, each of

which can individually lead to net costs, savings, or neither. Greater

differentiation of these services is necessary to fully understand both

the financial and health effects.

A 2010 study reported that in the United States, vaccinating

children, cessation of smoking, daily prophylactic use of aspirin, and screening of breast and colorectal cancers had the most potential to prevent premature death.

Preventive health measures that resulted in savings included

vaccinating children and adults, smoking cessation, daily use of

aspirin, and screening for issues with alcoholism, obesity, and vision

failure.

These authors estimated that if usage of these services in the United

States increased to 90% of the population, there would be net savings of

$3.7 billion, which comprised only about -0.2% of the total 2006 United States healthcare expenditure.

Despite the potential for decreasing healthcare spending, utilization

of healthcare resources in the United States still remains low,

especially among Latinos and African-Americans.

Overall, preventive services are difficult to implement because

healthcare providers have limited time with patients and must integrate a

variety of preventive health measures from different sources.

While these specific services bring about small net savings not

every preventive health measure saves more than it costs. A 1970s study

showed that preventing heart attacks by treating hypertension early on

with drugs actually did not save money in the long run. The money saved

by evading treatment from heart attack and stroke only amounted to about a quarter of the cost of the drugs.

Similarly, it was found that the cost of drugs or dietary changes to

decrease high blood cholesterol exceeded the cost of subsequent heart

disease treatment.

Due to these findings, some argue that rather than focusing healthcare

reform efforts exclusively on preventive care, the interventions that

bring about the highest level of health should be prioritized.

Cohen et al. (2008) outline a few arguments made by skeptics of

preventive healthcare. Many argue that preventive measures only cost

less than future treatment when the proportion of the population that

would become ill in the absence of prevention is fairly large.

The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group conducted a 2012 study

evaluating the costs and benefits (in quality-adjusted life-years or

QALYs) of lifestyle changes versus taking the drug metformin. They found

that neither method brought about financial savings, but were

cost-effective nonetheless because they brought about an increase in

QALYs.

In addition to scrutinizing costs, preventive healthcare skeptics also

examine efficiency of interventions. They argue that while many

treatments of existing diseases involve use of advanced equipment and

technology, in some cases, this is a more efficient use of resources

than attempts to prevent the disease.

Cohen et al. (2008) suggest that the preventive measures most worth

exploring and investing in are those that could benefit a large portion

of the population to bring about cumulative and widespread health

benefits at a reasonable cost.

- Cost-effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions

There are at least four nationally implemented childhood obesity

interventions in the United States: the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage excise

tax (SSB), the TV AD program, active physical education (Active PE)

policies, and early care and education (ECE) policies.

They each have similar goals of reducing childhood obesity. The

effects of these interventions on BMI have been studied, and the cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) has led to a better understanding of projected cost reductions and improved health outcomes.

The Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study (CHOICES)

was conducted to evaluate and compare the CEA of these four

interventions.

Gortmaker, S.L. et al. (2015) states: "The four initial

interventions were selected by the investigators to represent a broad

range of nationally scalable strategies to reduce childhood obesity

using a mix of both policy and programmatic strategies... 1. an excise

tax of $0.01 per ounce of sweetened beverages,

applied nationally and administered at the state level (SSB), 2.

elimination of the tax deductibility of advertising costs of TV

advertisements for "nutritionally poor" foods and beverages seen by

children and adolescents (TV AD), 3. state policy requiring all public

elementary schools in which physical education (PE) is currently

provided to devote ≥50% of PE class time to moderate and vigorous

physical activity (Active PE), and 4. state policy to make early child

educational settings healthier by increasing physical activity,

improving nutrition, and reducing screen time (ECE)."

The CHOICES found that SSB, TV AD, and ECE led to net cost

savings. Both SSB and TV AD increased quality adjusted life years and

produced yearly tax revenue of 12.5 billion US dollars and 80 million US

dollars, respectively.

Some challenges with evaluating the effectiveness of child obesity interventions include:

- The economic consequences of childhood obesity are both short and long term. In the short term, obesity impairs cognitive achievement and academic performance. Some believe this is secondary to negative effects on mood or energy, but others suggest there may be physiological factors involved. Furthermore, obese children have increased health care expenses (e.g. medications, acute care visits). In the long term, obese children tend to become obese adults with associated increased risk for a chronic condition such as diabetes or hypertension. Any effect on their cognitive development may also affect their contributions to society and socioeconomic status.

- In the CHOICES, it was noted that translating the effects of these interventions may in fact differ among communities throughout the nation. In addition it was suggested that limited outcomes are studied and these interventions may have an additional effect that is not fully appreciated.

- Modeling outcomes in such interventions in children over the long term is challenging because advances in medicine and medical technology are unpredictable. The projections from cost-effective analysis may need to be reassessed more frequently.

- The economics of preventive care in the US

The cost-effectiveness of preventive care is a highly debated topic.

While some economists argue that preventive care is valuable and

potentially cost saving, others believe it is an inefficient waste of

resources.[91]

Preventive care is composed of a variety of clinical services and

programs including annual doctor's check-ups, annual immunizations, and

wellness programs; recent models show that these simple interventions

can have significant economic impacts.

Clinical preventive services & programs

Research on preventive care addresses the question of whether it

is cost saving or cost effective and whether there is an economics

evidence base for health promotion and disease prevention. The need for

and interest in preventive care is driven by the imperative to reduce

health care costs while improving quality of care and the patient

experience. Preventive care can lead to improved health outcomes and

cost savings potential. Services such as health assessments/screenings, prenatal care, and telehealth and telemedicine can reduce morbidity or mortality with low cost or cost savings.

Specifically, health assessments/screenings have cost savings

potential, with varied cost-effectiveness based on screening and

assessment type. Inadequate prenatal care can lead to an increased risk of prematurity, stillbirth, and infant death. Time is the ultimate resource and preventive care can help mitigate the time costs.

Telehealth and telemedicine is one option that has gained consumer

interest, acceptance and confidence and can improve quality of care and

patient satisfaction.

Understanding the economics for investment

There are benefits and trade-offs when considering investment in

preventive care versus other types of clinical services. Preventive care

can be a good investment as supported by the evidence base and can

drive population health management objectives.

The concepts of cost saving and cost-effectiveness are different and

both are relevant to preventive care. For example, preventive care that

may not save money may still provide health benefits. Thus, there is a

need to compare interventions relative to impact on health and cost.

Preventive care transcends demographics and is applicable to

people of every age. The Health Capital Theory underpins the importance

of preventive care across the lifecycle and provides a framework for

understanding the variances in health and health care that are

experienced. It treats health as a stock that provides direct utility.

Health depreciates with age and the aging process can be countered

through health investments. The theory further supports that

individuals demand good health, that the demand for health investment is

a derived demand (i.e. investment is health is due to the underlying

demand for good health), and the efficiency of the health investment

process increases with knowledge (i.e. it is assumed that the more

educated are more efficient consumers and producers of health).

The prevalence elasticity of demand for prevention can also

provide insights into the economics. Demand for preventive care can

alter the prevalence rate of a given disease and further reduce or even

reverse any further growth of prevalence. Reduction in prevalence subsequently leads to reduction in costs.

Economics for policy action

There are a number of organizations and policy actions that are

relevant when discussing the economics of preventive care services. The

evidence base, viewpoints, and policy briefs from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and efforts by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

all provide examples that improve the health and well-being of

populations (e.g. preventive health assessments/screenings, prenatal

care, and telehealth/telemedicine). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, ACA)

has major influence on the provision of preventive care services,

although it is currently under heavy scrutiny and review by the new

administration. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

the ACA makes preventive care affordable and accessible through

mandatory coverage of preventive services without a deductible,

copayment, coinsurance, or other cost sharing.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a panel of

national experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, works to

improve health of Americans by making evidence-based recommendations

about clinical preventive services.

They do not consider the cost of a preventive service when determining

a recommendation. Each year, the organization delivers a report to

Congress that identifies critical evidence gaps in research and

recommends priority areas for further review.

The National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (NNPQC),

sponsored by the CDC, supports state-based perinatal quality

collaboratives (PQCs) in measuring and improving upon health care and

health outcomes for mothers and babies. These PQCs have contributed to

improvements such as reduction in deliveries before 39 weeks, reductions

in healthcare associated blood stream infections, and improvements in

the utilization of antenatal corticosteroids.

Telehealth and telemedicine has realized significant growth and

development recently. The Center for Connected Health Policy (The

National Telehealth Policy Resource Center) has produced multiple

reports and policy briefs on the topic of Telehealth and Telemedicine

and how they contribute to preventive services.

Policy actions and provision of preventive services do not

guarantee utilization. Reimbursement has remained a significant

barrier to adoption due to variances in payer and state level

reimbursement policies and guidelines through government and commercial

payers. Americans use preventive services at about half the recommended

rate and cost-sharing, such as deductibles, co-insurance, or

copayments, also reduce the likelihood that preventive services will be

used.

Further, despite the ACA's enhancement of Medicare benefits and

preventive services, there were no effects on preventive service

utilization, calling out the fact that other fundamental barriers exist.

- The Affordable Care Act and preventive healthcare

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as just

the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare, was passed and became law in the

United States on March 23, 2010.

The finalized and newly ratified law was to address many issues in the

U.S. healthcare system, which included expansion of coverage, insurance

market reforms, better quality, and the forecast of efficiency and

costs.

Under the insurance market reforms the act required that insurance

companies no longer exclude people with pre-existing conditions, allow

for children to be covered on their parents' plan until the age of 26,

and expand appeals that dealt with reimbursement denials. The Affordable

Care Act also banned the limited coverage imposed by health insurances,

and insurance companies were to include coverage for preventive health

care services.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has categorized and rated

preventive health services as either ‘”A” or “B”, as to which insurance

companies must comply and present full coverage. Not only has the U.S.

Preventive Services Task Force provided graded preventive health

services that are appropriate for coverage, they have also provided many

recommendations to clinicians and insurers to promote better preventive

care to ultimately provide better quality of care and lower the burden

of costs.

Health insurance and preventive care

Healthcare insurance companies are willing to pay for preventive care

despite the fact that patients are not acutely sick in hope that it will

prevent them from developing a chronic disease later on in life. Today, health insurance plans offered through the Marketplace, mandated by the Affordable Care Act are required to provide certain preventive care services free of charge to patients. Section 2713

of the Affordable Care Act, specifies that all private Marketplace and

all employer-sponsored private plans (except those grandfathered in) are

required to cover preventive care services that are ranked A or B by

the US Preventive Services Task Force free of charge to patients.

For example, UnitedHealthcare insurance company has published patient

guidelines at the beginning of the year explaining their preventive care

coverage.

Evaluating incremental benefits of preventive care

Evaluating the incremental benefits of preventive care requires a longer

period of time when compared to acutely ill patients. Inputs into the

model such as discounting rate and time horizon can have significant

effects on the results. One controversial subject is use of a 10-year

time frame to assess cost effectiveness of diabetes preventive services

by the Congressional Budget Office.

The preventive care services mainly focus on chronic disease.

The Congressional Budget Office has provided guidance that further

research is needed in the area of the economic impacts of obesity in the

US before the CBO can estimate budgetary consequences. A bipartisan

report published in May 2015 recognizes the potential of preventive care

to improve patients' health at individual and population levels while

decreasing the healthcare expenditure.

An economic case for preventive health

Mortality from modifiable risk factors

Chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, obesity

and cancer have become the most common and costly health problems in

the United States. In 2014, it was projected that by 2023 that the

number of chronic disease cases would increase by 42%, resulting in $4.2

trillion in treatment and lost economic output. They are also among the top ten leading causes of mortality.

Chronic diseases are driven by risk factors that are largely

preventable. Sub-analysis performed on all deaths in the United States

in the year 2000 revealed that almost half were attributed to

preventable behaviors including tobacco, poor diet, physical inactivity

and alcohol consumption. More recent analysis reveals that heart disease and cancer alone accounted for nearly 46% of all deaths.

Modifiable risk factors are also responsible for a large morbidity

burden, resulting in poor quality of life in the present and loss of

future life earning years. It is further estimated that by 2023, focused

efforts on the prevention and treatment of chronic disease may result

in 40 million fewer chronic disease cases, potentially reducing

treatment costs by $220 billion.

Childhood vaccinations reduce health care costs

Childhood immunizations are largely responsible for the increase

in life expectancy in the 20th century. From an economic standpoint,

childhood vaccines demonstrate a very high return on investment.

According to Healthy People 2020, for every birth cohort that receives

the routine childhood vaccination schedule, direct health care costs are

reduced by $9.9 billion and society saves $33.4 billion in indirect

costs.

The economic benefits of childhood vaccination extend beyond individual

patients to insurance plans and vaccine manufacturers, all while

improving the health of the population.

Prevention and health capital theory

The burden of preventable illness extends beyond the healthcare

sector, incurring significant costs related to lost productivity among

workers in the workforce. Indirect costs related to poor health

behaviors and associated chronic disease costs U.S. employers billions

of dollars each year.

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA),

medical costs for employees with diabetes are twice as high as for

workers without diabetes and are caused by work-related absenteeism ($5

billion), reduced productivity at work ($20.8 billion), inability to

work due to illness-related disability ($21.6 billion), and premature

mortality ($18.5 billion). Reported estimates of the cost burden due to

increasingly high levels of overweight and obese members in the

workforce vary,

with best estimates suggesting 450 million more missed work days,

resulting in $153 billion each year in lost productivity, according to

the CDC Healthy Workforce.

In the field of economics, the Health Capital model explains how

individual investments in health can increase earnings by “increasing

the number of healthy days available to work and to earn income.”

In this context, health can be treated both as a consumption good,

wherein individuals desire health because it improves quality of life in

the present, and as an investment good because of its potential to

increase attendance and workplace productivity over time. Preventive

health behaviors such as healthful diet, regular exercise, access to and

use of well-care, avoiding tobacco, and limiting alcohol can be viewed

as health inputs that result in both a healthier workforce and

substantial cost savings.

Preventive care and quality adjusted life years.

Health benefits of preventive care measures can be described in terms of quality-adjusted life-years

(QALYs) saved. A QALY takes into account length and quality of life,

and is used to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of medical and preventive

interventions. Classically, one year of perfect health is defined as 1

QALY and a year with any degree of less than perfect health is assigned a

value between 0 and 1 QALY.

As an economic weighting system, the QALY can be used to inform

personal decisions, to evaluate preventive interventions and to set

priorities for future preventive efforts.

Cost-saving and cost-effective benefits of preventive care

measures are well established. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

evaluated the prevention cost-effectiveness literature, and found that

many preventive measures meet the benchmark of <$100,000 per QALY and

are considered to be favorably cost-effective.

These include screenings for HIV and chlamydia, cancers of the colon,

breast and cervix, vision screening, and screening for abdominal aortic

aneurysms in men >60 in certain populations. Alcohol and tobacco

screening were found to be cost-saving in some reviews and

cost-effective in others. According to the RWJF analysis, two preventive

interventions were found to save costs in all reviews: childhood

immunizations and counseling adults on the use of aspirin.

Prevention in minority populations

Health disparities are increasing in the United States for

chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular

disease. Populations at heightened risk for health inequities are the

growing proportion of racial and ethnic minorities, including African

Americans, American Indians, Hispanics/Latinos, Asian Americans, Alaska

Natives and Pacific Islanders.

According to the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH),

a national CDC program, non-Hispanic blacks currently have the highest

rates of obesity (48%), and risk of newly diagnosed diabetes is 77%

higher among non-Hispanic blacks, 66% higher among Hispanics/Latinos and

18% higher among Asian Americans compared to non-Hispanic whites.

Current U.S. population projections predict that more than half of

Americans will belong to a minority group by 2044.

Without targeted preventive interventions, medical costs from chronic

disease inequities will become unsustainable. Broadening health policies

designed to improve delivery of preventive services for minority

populations may help reduce substantial medical costs caused by

inequities in health care, resulting in a return on investment.

Policies of prevention

Chronic disease

is a population level issue that requires population health level

efforts and national and state level public policy to effectively

prevent, rather than individual level efforts. The United States

currently employs many public health policy efforts aligned with the

preventive health efforts discussed above. For instance, the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention support initiatives such as Health in

All Policies and HI-5 (Health Impact in 5 Years), collaborative efforts

that aim to consider prevention across sectors and address social determinants of health as a method of primary prevention for chronic disease.

Specific examples of programs targeting vaccination and obesity

prevention in childhood are discussed in the sections to follow.

Policy prevention of obesity

Policies that address the obesity epidemic should be proactive

and far-reaching, including a variety of stakeholders both in healthcare

and in other sectors. Recommendations from the Institute of Medicine in

2012 suggest that “…concerted action be taken across and within five

environments (physical activity (PA), food and beverage, marketing and

messaging, healthcare and worksites, and schools) and all sectors of

society (including government, business and industry, schools, child

care, urban planning, recreation, transportation, media, public health,

agriculture, communities, and home) in order for obesity prevention

efforts to truly be successful.”

There are dozens of current policies acting at either (or all of)

the federal, state, local and school levels. Most states employ a

physical education requirement of 150 minutes of physical education per

week at school, a policy of the National Association of Sport and

Physical Education. In some cities, including Philadelphia, a sugary

food tax is employed. This is a part of an amendment to Title 19 of the

Philadelphia Code, “Finance, Taxes and Collections”; Chapter 19-4100,

“Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax, that was approved 2016, which establishes

an excise tax of $0.015 per fluid ounce on distributors of beverages

sweetened with both caloric and non-caloric sweeteners.

Distributors are required to file a return with the department, and the

department can collect taxes, among other responsibilities.

These policies can be a source of tax credits. For example, under

the Philadelphia policy, businesses can apply for tax credits with the

revenue department on a first-come, first-served basis. This applies

until the total amount of credits for a particular year reaches one

million dollars.

Recently, advertisements for food and beverages directed at

children have received much attention. The Children's Food and Beverage

Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) is a self-regulatory program of the food

industry. Each participating company makes a public pledge that details

its commitment to advertise only foods that meet certain nutritional

criteria to children under 12 years old.

This is a self-regulated program with policies written by the Council

of Better Business Bureaus. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded

research to test the efficacy of the CFBAI. The results showed progress

in terms of decreased advertising of food products that target children

and adolescents.

To explore other programs and initiatives related to policies of

childhood obesity, visit the following organizations and online

databases:

U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation-supported Bridging the Gap Program,

National Association of County and City Health Officials,

Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Chronic Disease State

Policy Tracking System,

National Conference of State Legislatures,

Prevention Institute's ENACT local policy database,

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Childhood immunization policies

Despite nationwide controversies over childhood vaccination and

immunization, there are policies and programs at the federal, state,

local and school levels outlining vaccination requirements. All states

require children to be vaccinated against certain communicable diseases

as a condition for school attendance. However, currently 18 states allow

exemptions for “philosophical or moral reasons.” Diseases for which

vaccinations form part of the standard ACIP vaccination schedule are

diphtheria tetanus pertussis (whooping cough), poliomyelitis (polio),

measles, mumps, rubella, haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B,

influenza, and pneumococcal infections. These schedules can be viewed on the CDC website.

The CDC website describes a federally funded program, Vaccines

for Children (VFC), which provides vaccines at no cost to children who

might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay.

Additionally, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)

is an expert vaccination advisory board that informs vaccination policy

and guides on-going recommendations to the CDC, incorporating the most

up-to-date cost-effectiveness and risk-benefit evidence in its

recommendations.

An economic case conclusion

There are economic and health related arguments for preventive

healthcare. Direct and indirect medical costs related to preventable

chronic disease are high, and will continue to rise with an aging and

increasingly diverse U.S. population. The government, at federal, state,

local and school levels has acknowledged this and created programs and

policies to support chronic disease prevention, notably at the childhood

age, and focusing on obesity prevention and vaccination. Economically,

with an increase in QALY and a decrease in lost productivity over a

lifetime, existing and innovative prevention interventions demonstrate a

high return on investment and are expected to result in substantial

healthcare cost-savings over time.

![S(t)=p+[(1-p)\times S^{*}(t)]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8925c84b869b425dd216b7d4df5c8627124576c7) ,

,