Christian anarchism is a movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels.

It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority

to which Christians are ultimately answerable—the authority of God as

embodied in the teachings of Jesus.

It therefore rejects the idea that human governments have ultimate

authority over human societies. Christian anarchists denounce the state, believing it is violent, deceitful and, when glorified, idolatrous.

Christian anarchists hold that the "Reign of God" is the proper

expression of the relationship between God and humanity. Under the

"Reign of God", human relationships would be characterized by divided

authority, servant leadership,

and universal compassion—not by the hierarchical, authoritarian

structures that are normally attributed to religious social order. Most Christian anarchists are pacifists—they reject war and the use of violence.

More than any other Bible source, the Sermon on the Mount is used as the basis for Christian anarchism. Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You is often regarded as a key text for modern Christian anarchism.

More than any other Bible source, the Sermon on the Mount is used as the basis for Christian anarchism. Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You is often regarded as a key text for modern Christian anarchism.

Origins

Old Testament

Jacques Ellul, a French philosopher and Christian anarchist, notes that the final verse of the Book of Judges (Judges 21:25) states that there was no king in Israel and that "everyone did as they saw fit".

Subsequently, as recorded in the first Book of Samuel (1 Samuel 8) the people of Israel wanted a king "so as to be like other nations".

God declared that the people had rejected him as their king. He warned that a human king would lead to militarism, conscription and taxation, and that their pleas for mercy from the king's demands would go unanswered. Samuel passed on God's warning to the Israelites but they still demanded a king, and Saul became their ruler.

Much of the subsequent Old Testament chronicles the Israelites trying to live with this decision.

New Testament

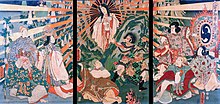

Carl Heinrich Bloch's depiction of the Sermon on the Mount

More than any other Bible source, the Sermon on the Mount is used as the basis for Christian anarchism. Alexandre Christoyannopoulos explains that the Sermon perfectly illustrates Jesus's central teaching of love and forgiveness. Christian anarchists claim that the state, founded on violence, contravenes the Sermon and Jesus' call to love our enemies.

The gospels tell of Jesus's temptation in the desert.

For the final temptation, Jesus is taken up to a high mountain by Satan

and told that if he bows down to Satan he will give him all the

kingdoms of the world.

Christian anarchists use this as evidence that all Earthly kingdoms and

governments are ruled by Satan, otherwise they would not be Satan's to

give.

Jesus refuses the temptation, choosing to serve God instead, implying

that Jesus is aware of the corrupting nature of Earthly power.

Christian eschatology and various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the state and political power as the Beast in the Book of Revelation.

Friedrich Nietzsche and Frank Seaver Billings criticize Christianity and anarchism by arguing that they are the same thing.

Early Church

According to Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, several of the Church Fathers' writings suggest anarchism as God's ideal. The first Christians opposed the primacy of the State: "We must obey God as ruler rather than men" (Acts 4:19, 5:29, 1 Corinthians

6:1-6); "Stripping the governments and the authorities bare, he

exhibited them in open public as conquered, leading them in a triumphal

procession by means of it." (Colossians 2:15). Also some early Christian communities appear to have practised anarchist communism, such as the Jerusalem group described in Acts, who shared their money and labour equally and fairly among the members.

Roman Montero claims that using an anthropological framework, such as

that of anarchist David Graeber, one can plausibly reconstruct the

communism of these early Christian communities and that these practices

were widespread, long-lasting and substantial.

Christian anarchists, such as Kevin Craig, insist that these

communities were centred on true love and care for one another rather

than liturgy. They also allege that the reason the early Christians were persecuted was not because they worshipped Jesus Christ, but because they refused to worship human idols claiming divine status. Given that they refused to worship the Roman Emperor they refused to swear any oath of allegiance to the Empire. For example, when requested that he swear by the emperor, Speratus, spokesperson of the Scillitan Martyrs, said in 180ce, "I recognize not the empire of this world... because I know my Lord, the King of kings and Emperor of all nations.

Thomas Merton in his introduction to a translation of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers describes the early monastics as "Truly in certain sense 'anarchists,' and it will do no harm to think of them as such."

During the Ante-Nicene Period there were several independent sects who took a radically different approach to Christianity than the Proto-Orthodox Church and displayed anarchist tendencies by relying on direct revelation rather than scripture. For example:

- Gnosticism (particularly Valentinianism) – 2nd to 4th centuries – reliance on revealed knowledge from a transcendent, unknowable God, who was a distinct divinity from the Demiurge who created and oversees the material world.

- Montanism – 2nd century – relied on prophetic revelations from the Holy Spirit.

Conversion of the Roman Empire

For Christian anarchists the moment which epitomises the degeneration of Christianity is the conversion of Emperor Constantine after his victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312. Following this event Christianity was legalized under the Edict of Milan in 313, hastening the Church's transformation from a humble bottom-up sect to an authoritarian top-down organization. Christian anarchists point out that this marked the beginning of the "Constantinian shift", in which Christianity gradually came to be identified with the will of the ruling elite, becoming the State church of the Roman Empire, and in some cases (such as the Crusades, Inquisition and Wars of Religion) a religious justification for violence.

Middle Ages

There were many groups and individuals in the Middle Ages who displayed anarchist tendencies, taking God as their guide and rejecting both church and secular authority.

- Paulicians – an Armenian group (6th to 9th centuries) who sought a return to the purity of the church at the time of Paul the Apostle.

- Tondrakians – an Armenian group (9th to 11th centuries) who advocated the abolition of the Church along with all its traditional rites.

- Bogomils – a group arising in the 11th century in Macedonia and the Balkans who sought a return to the spirituality of the early Christians and opposed established forms of government and church.

- Gundolfo – an itinerant 11th century preacher near Lille, France, who taught that salvation was achieved through a virtuous life of abandoning the world, restraining the appetites of the flesh, earning food by the labor of hands, doing no injury to anyone, and extending charity to everyone of their own faith.

- Arnoldists – a 12th century group from Lombardy who criticized the wealth of the Catholic Church and preached against baptism and the Eucharist.

- Petrobrusians were 12th century followers of Peter of Bruys in southeastern France who rejected the authority of the Church Fathers and of the Catholic Church, opposing clerical celibacy, infant baptism, prayers for the dead and organ music.

- Henricans were 12th century followers of Henry of Lausanne in France. They rejected the doctrinal and disciplinary authority of the church, did not recognize any form of worship or liturgy and denied the sacraments.

- Waldensians – a movement that began in the 12th century in Lyon, France, and still exists today. They held that Apostolic poverty was the way to spiritual perfection and rejected what they perceived as the idolatry of the Catholic Church.

- Brethren of the Free Spirit – a term applied in the 13th century to those, primarily in the Low Countries, Germany, France, Bohemia and northern Italy, who believed that the sacraments were unnecessary for salvation, that the soul could be perfected through imitating the life of Christ, and that the perfected soul was free of sin and beyond all ecclesiastical, moral and secular law.

- Apostolic Brethren (later known as Dulcinians) – a 13th to 14th century sect from northern Italy founded by Gerard Segarelli and continued by Fra Dolcino of Novara. The Apostolic Brethren rejected the worldliness of the church and sought a life of perfect sanctity, in complete poverty, with no fixed domicile, no care for the morrow, and no vows. The Dulcinians claimed that they were inaugurating a new era characterized by poverty, chastity, and the absence of government.

- Fraticelli (or Spiritual Franciscans) – Franciscan extremists (13th to 15th centuries) who regarded the wealth of the Church as scandalous.

- Neo-Adamites – a term applied in the 13th to 15th centuries to those, including Taborites, Picards and some Beghards, who wished to return to the purity of the life of Adam by living communally, practicing social and religious nudity, embracing free love, rejecting marriage and individual ownership of property.

- Nicholas of Basel – a 14th century Swiss leader who, after a spiritual experience, taught that he had the authority to use episcopal and priestly powers (even though he was not ordained), that submission to his direction was necessary for attaining spiritual perfection, and that his followers could not sin even though they committed crimes or disobeyed both the Church and pope.

- Petr Chelčický, a 15th-century Czech leader who taught that violent punishment was immoral, and that Christians should not accept government office or appeal to government authority

Peasant revolts in the post-reformation era

Woodcut from a Diggers document by William Everard.

Various libertarian socialist authors have identified the written work of English Protestant social reformer Gerrard Winstanley and the social activism of his group, the Diggers, as anticipating this line of thought. For anarchist historian George Woodcock "Although (Pierre Joseph) Proudhon

was the first writer to call himself an anarchist, at least two

predecessors outlined systems that contain all the basic elements of

anarchism. The first was Gerrard Winstanley

(1609–c. 1660), a linen draper who led the small movement of the

Diggers during the Commonwealth. Winstanley and his followers protested

in the name of a radical Christianity against the economic distress that

followed the Civil War and against the inequality that the grandees of the New Model Army seemed intent on preserving.

In 1649–1650 the Diggers squatted on stretches of common land in

southern England and attempted to set up communities based on work on

the land and the sharing of goods. The communities failed following a

crackdown by the English authorities, but a series of pamphlets by

Winstanley survived, of which The New Law of Righteousness (1649)

was the most important. Advocating a rational Christianity, Winstanley

equated Christ with “the universal liberty” and declared the universally

corrupting nature of authority. He saw “an equal privilege to share in

the blessing of liberty” and detected an intimate link between the

institution of property and the lack of freedom." For Murray Bookchin

"In the modern world, anarchism first appeared as a movement of the

peasantry and yeomanry against declining feudal institutions. In Germany

its foremost spokesman during the Peasant Wars was Thomas Müntzer;

in England, Gerrard Winstanley, a leading participant in the Digger

movement. The concepts held by Müntzer and Winstanley were superbly

attuned to the needs of their time — a historical period when the

majority of the population lived in the countryside and when the most

militant revolutionary forces came from an agrarian world. It would be

painfully academic to argue whether Müntzer and Winstanley could have

achieved their ideals. What is of real importance is that they spoke to

their time; their anarchist concepts followed naturally from the rural

society that furnished the bands of the peasant armies in Germany and

the New Model in England."

Modern era

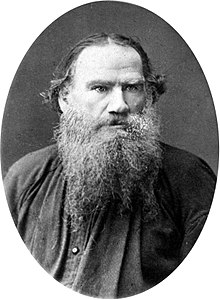

Leo Tolstoy wrote extensively about Christian pacifism and anarchism.

Nineteenth century Christian abolitionist Adin Ballou

was critical of government and believed that it would be supplanted by a

new order in which individuals are guided solely by their love for God. His writings heavily influenced Leo Tolstoy, who wrote extensively on his anarchist principles and their descension from his Christian faith, in books including The Kingdom of God is Within You, a key Christian anarchist text. Tolstoy sought to separate Russian Orthodox Christianity — which was merged with the state — from what he believed was the true message of Jesus as contained in the Gospels, specifically in the Sermon on the Mount.

He takes the viewpoint that all governments who wage war, and churches

who in turn support those governments, are an affront to the Christian

principles of nonviolence. Although Tolstoy never actually used the term "Christian anarchism" in The Kingdom of God Is Within You, reviews of this book following its publication in 1894 appear to have coined the term.

Antireligious former priest Thomas J. Hagerty was a primary author of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Preamble ("an injury to one is an injury to all"). IWW members included Christian anarchists like Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennacy.

Dorothy Day was a journalist turned social activist who became

known for her social justice campaigns in defense of the poor. Alongside

Peter Maurin, she founded the Catholic Worker Movement in 1933, espousing nonviolence, and hospitality for the impoverished and downtrodden. Dorothy Day was declared Servant of God when a cause for sainthood was opened for her by Pope John Paul II. Dorothy Day's Distributist economic views are very similar to Proudhon's mutualism whom she was influenced by. Day also named the phrase "precarious work" based on former anarcho-communist Léonce Crenier's embrace of poverty. Peter Maurin's vision to transform the social order consisted of establishing urban houses of hospitality to care for the destitute; rural farming communities to teach city dwellers agrarianism and encourage a movement back-to-the-land; and roundtable discussions in community centres to clarify thought and initiate action.

Anarchist biblical views and practices

Church authority

With some notable exceptions, such as the Catholic Worker Movement, many Christian anarchists are critical of Church dogma and rituals. Christian anarchists tend to wish that Christians were less preoccupied with performing rituals and preaching dogmatic theology, and more with following Jesus' teaching and practices. Jacques Ellul and Dave Andrews claim that Jesus did not intend to be the founder of an institutional religion, while Michael Elliot believes one of Jesus' intentions was to bypass human intermediaries and do away with priests.

Pacifism and nonviolence

The Deserter (1916) by Boardman Robinson.

Christian anarchists, such as David Lipscomb, Leo Tolstoy, Ammon Hennacy, Jacques Ellul, and Dave Andrews, follow Jesus' call to not resist evil but turn the other cheek. They argue that this teaching can only imply a condemnation of the state, as the police and army hold a monopoly over the legitimate use of force. They believe freedom

will only be guided by the grace of God if they show compassion to

others and turn the other cheek when confronted with violence. Christian

anarchists believe violence begets violence and the ends never justify the means.

Many Christian anarchists practice the principles of nonviolence, nonresistance, and turning the other cheek. To illustrate how nonresistance works in practice, Alexandre Christoyannopoulos offers the following Christian anarchist response to terrorism:

The path shown by Jesus is a difficult one that can only be trod by true martyrs. A "martyr," etymologically, is he who makes himself a witness to his faith. And it is the ultimate testimony to one’s faith to be ready to put it to practice even when one’s very life is threatened. But the life to be sacrificed, it should be noted, is not the enemy’s life, but the martyr’s own life — killing others is not a testimony of love, but of anger, fear, or hatred. For Tolstoy, therefore, a true martyr to Jesus’ message would neither punish nor resist (or at least not use violence to resist), but would strive to act from love, however hard, whatever the likelihood of being crucified. He would patiently learn to forgive and turn the other cheek, even at the risk of death. Such would be the only way to eventually win the hearts and minds of the other camp and open up the possibilities for reconciliation in the "war on terror."

Simple living

Christian anarchists, such as Ammon Hennacy, Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day, often advocate voluntary poverty.

This can be for a variety of reasons, such as withdrawing support for

government by reducing taxable income or following Jesus' teachings. Jesus appears to teach voluntary poverty when he told his disciples, "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God" (Mark 10:25) and "You cannot serve both God and Mammon" (Luke 16:13).

State authority

The most common challenge for anarchist theologians is interpreting Paul's Epistle to the Romans 13:1–7, in which Paul demanded obedience to governing authorities and described them as God's servants exacting punishment on wrongdoers. Romans 13:1–7 holds the most explicit reference to the state in the New Testament but other parallel texts include Titus 3:1, Hebrews 13:17 and 1 Peter 2:13-17.

Blessed are the Peacemakers (1917) by George Bellows

Some theologians, such as C.E.B. Cranfield,

have interpreted Romans 13:1–7 to mean the Church should support the

state, as God has sanctified the state to be his main tool to preserve

social order. Similarly, in the case of the state being involved in a "just war", some theologians argue that it's permissible for Christians to serve the state and wield the sword. Christian anarchists do not share these interpretations of Romans 13 but still recognize it as "a very embarrassing passage."

Christian anarchists and pacifists, such as Jacques Ellul and Vernard Eller, do not attempt to overthrow the state given Romans 13 and Jesus' command to turn the other cheek. As wrath and vengeance are contrary to the Christian values of kindness and forgiveness, Ellul neither supports, nor participates in, the state. Eller articulates this position by restating the passage this way:

Be clear, any of those human [authorities] are where they are only because God is allowing them to be there. They exist only at his sufferance. And if God is willing to put up with...the Roman Empire, you ought to be willing to put up with it, too. There is no indication God has called you to clear it out of the way or get it converted for him. You can't fight an Empire without becoming like the Roman Empire; so you had better leave such matters in God's hands where they belong.

Christians who interpret Romans 13 as advocating support for governing authorities are left with the difficulty of how to act under tyrants or dictators. Ernst Käsemann, in his Commentary on Romans,

challenged the mainstream Christian interpretation of the passage in

light of German Lutheran Churches using this passage to justify the Holocaust.

Paul's letter to Roman Christians declares "For rulers hold no

terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong." However

Christian anarchists point out an inconsistency if this text were to be

taken literally and in isolation as Jesus and Paul were both executed by

the governing authorities or "rulers" even though they did "right."

There are also Christians anarchists, such as Tolstoy and Hennacy, who do not see the need to integrate Paul's teachings into their subversive

way of life. Tolstoy believed Paul was instrumental in the church's

"deviation" from Jesus' teaching and practices, whilst Hennacy believed

"Paul spoiled the message of Christ" (see Jesuism). Hennacy and Ciaron O'Reilly, in contrast to Eller, advocate nonviolent civil disobedience to confront state oppression.

Swearing of oaths

In the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:33-37) Jesus tells his followers to not swear oaths in the name of God or Man. Tolstoy, Adin Ballou and Petr Chelčický

understand this to mean that Christians should never bind themselves to

any oath as they may not be able to fulfil the will of God if they are

bound to the will of a fellow-man. Tolstoy takes the view that all oaths

are evil, but especially an oath of allegiance.

Tax

Some Christian anarchists resist taxes in the belief that their government is engaged in immoral, unethical or destructive activities such as war, and paying taxes inevitably funds these activities, whilst others submit to taxation.

Adin Ballou wrote that if the act of resisting taxes requires physical

force to withhold what a government tries to take, then it is important

to submit to taxation. Ammon Hennacy, who, like Ballou also believed in

nonresistance, eased his conscience by simply living below the income tax threshold.

Christian anarchists do not interpret the injunction in Matthew 22:21 to "give to Caesar what is Caesar's" as advocating support for taxes, but as further advice to free oneself from material attachment. For example, Dorothy Day said if we were to give everything to God there will be nothing left for Caesar, and Jacques Ellul believed the passage showed that Caesar may have rights over fiat money but not things that are made by God, as he explained:

"Render unto Caesar..." in no way divides the exercise of authority into two realms....They were said in response to another matter: the payment of taxes, and the coin. The mark on the coin is that of Caesar; it is the mark of his property. Therefore give Caesar this money; it is his. It is not a question of legitimizing taxes! It means that Caesar, having created money, is its master. That's all. Let us not forget that money, for Jesus, is the domain of Mammon, a satanic domain!

Vegetarianism

Vegetarianism in the Christian tradition has a long history commencing in the first centuries of Church with the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers who abandoned the "world of men" for intimacy with the God of Jesus Christ. Vegetarianism amongst hermits and Christian monastics in the Eastern Christian and Roman Catholic traditions remains common to this day as a means of simplifying one's life, and as a practice of asceticism. Leo Tolstoy, Ammon Hennacy, and Théodore Monod extended their belief in nonviolence and compassion to all living beings through vegetarianism.

Present-day Christian anarchist groups

Brotherhood Church

The Brotherhood Church is a Christian anarchist and pacifist community. The Brotherhood Church can be traced back to 1887 when a Congregationalist minister called John Bruce Wallace started a magazine called "The Brotherhood" in Limavady, Northern Ireland. An intentional community with Quaker origins has been located at Stapleton, near Pontefract, Yorkshire, since 1921.

Catholic Worker Movement

Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Workers.

Established by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day in the early 1930s, the Catholic Worker Movement is a Christian movement dedicated to nonviolence, personalism and voluntary poverty. Over 130 Catholic Worker communities exist in the United States where "houses of hospitality" care for the homeless. The Joe Hill House

of hospitality (which closed in 1968) in Salt Lake City, Utah featured

an enormous twelve feet by fifteen foot mural of Jesus Christ and Joe Hill. Present-day Catholic Workers include Ciaron O'Reilly, an Irish-Australian civil rights and anti-war activist.

Anne Klejment, professor of history at University of St. Thomas, wrote of the Catholic Worker Movement:

The Catholic Worker considered itself a Christian anarchist movement. All authority came from God; and the state, having by choice distanced itself from Christian perfectionism, forfeited its ultimate authority over the citizen...Catholic Worker anarchism followed Christ as a model of nonviolent revolutionary behavior...He respected individual conscience. But he also preached a prophetic message, difficult for many of his contemporaries to embrace.

The Catholic Worker Movement has consistently protested against war

and violence for over seven decades. Many of the leading figures in the

movement have been both anarchists and pacifists, as Ammon Hennacy explains:

Christian Anarchism is based upon the answer of Jesus to the Pharisees when Jesus said that he without sin should be the first to cast the stone, and upon the Sermon on the Mount which advises the return of good for evil and the turning of the other cheek. Therefore, when we take any part in government by voting for legislative, judicial, and executive officials, we make these men our arm by which we cast a stone and deny the Sermon on the Mount. The dictionary definition of a Christian is one who follows Christ; kind, kindly, Christ-like. Anarchism is voluntary cooperation for good, with the right of secession. A Christian anarchist is therefore one who turns the other cheek, overturns the tables of the moneychangers, and does not need a cop to tell him how to behave. A Christian anarchist does not depend upon bullets or ballots to achieve his ideal; he achieves that ideal daily by the One-Man Revolution with which he faces a decadent, confused, and dying world.

Maurin and Day were both baptized and confirmed in the Catholic

Church and believed in the institution, thus showing it is possible to

be a Christian anarchist and still choose to remain within a church.

After her death, Day was proposed for sainthood by the Claretian Missionaries in 1983. Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York permission to open Day's cause for sainthood in March 2000, calling her a Servant of God.

In literature, in Michael Paraskos's 2017 novel, Rabbitman, a political satire prompted by Donald Trump's

presidency, the heroine, called Angela Witney, is a member of an

imagined Catholic Worker commune located in the southern English village

of Ditchling, where the artist Eric Gill once lived.

Online communities

Essays in Anarchism and Religion (edited by Matthew Adams and Alexandre Christoyannopoulos, 2017)

Numerous Christian anarchist websites, social networking sites, forums, electronic mailing lists and blogs

have emerged on the internet over the last few years. These include:

The AnarchoChristian Podcast and Website, Biblical Anarchy: Obey God

Rather Than Men, The Libertarian Christian Institute, started by Norman

Horn, A Pinch of Salt, a 1980s Christian anarchist magazine, revived in 2006 by Keith Hebden as a blog and bi-annual magazine; Libera Catholick Union founded in 1988 and re-organized in 2019; Jesus Radicals founded by Mennonites in 2000; Lost Religion of Jesus created in 2005; Christian Anarchists created in 2006; The Mormon Worker, a blog and newspaper, founded in 2007 to promote Mormonism, anarchism and pacifism; and Academics and Students Interested in Religious Anarchism (ASIRA) founded by Alexandre Christoyannopoulos in 2008.

Christian anarchism in the arts

The Charter of the Forest

is a regularly updating Read-Opera that espouses Christian anarchist

values such as opposition to hierarchy and complete commitment to

non-violence. The composer, Matthew Buckwalter, is highly influenced by

Tolstoy, particularly The Kingdom of God is Within You, and the various speeches and writings of Noam Chomsky, among other philosophical sources.

Criticism

Critics of Christian anarchism include both Christians and anarchists. Christians often cite Romans 13 as evidence that the State should be obeyed, while secular anarchists do not believe in any authority including God as per the slogan "no gods, no masters". Christian anarchists often believe Romans 13 is taken out of context, emphasizing that Revelation 13 and Isaiah 13, among other passages, are needed to fully understand Romans 13 text.