Globalization, the flow of information, goods, capital, and people across political and geographic boundaries, allows infectious diseases to rapidly spread around the world, while also allowing the alleviation of factors such as hunger and poverty, which are key determinants of global health. The spread of diseases across wide geographic scales has increased through history. Early diseases that spread from Asia to Europe were bubonic plague, influenza of various types, and similar infectious diseases.

In the current era of globalization, the world is more interdependent than at any other time. Efficient and inexpensive transportation has left few places inaccessible, and increased global trade in agricultural products has brought more and more people into contact with animal diseases that have subsequently jumped species barriers.

Globalization intensified during the Age of Exploration, but trading routes had long been established between Asia and Europe, along which diseases were also transmitted. An increase in travel has helped spread diseases to natives of lands who had not previously been exposed. When a native population is infected with a new disease, where they have not developed antibodies through generations of previous exposure, the new disease tends to run rampant within the population.

Etiology, the modern branch of science that deals with the causes of infectious disease, recognizes five major modes of disease transmission: airborne, waterborne, bloodborne, by direct contact, and through vector (insects or other creatures that carry germs from one species to another). As humans began traveling over seas and across lands which were previously isolated, research suggests that diseases have been spread by all five transmission modes.

Travel patterns and globalization

The Age of Exploration generally refers to the period between the 15th and 17th centuries. During this time, technological advances in shipbuilding

and navigation made it easier for nations to explore outside previous

boundaries. Globalization has had many benefits, for example, new

products to Europeans were discovered, such as tea, silk and sugar when Europeans developed new trade routes around Africa to India and the Spice Islands, Asia, and eventually running to the Americas.

In addition to trading in goods, many nations began to trade in slavery.

Trading in slaves was another way by which diseases were carried to new

locations and peoples, for instance, from sub-Saharan Africa to the

Caribbean and the Americas. During this time, different societies began to integrate, increasing the concentration of humans and animals in certain places, which led to the emergence of new diseases as some jumped in mutation from animals to humans.

During this time sorcerers' and witch doctors' treatment of disease was often focused on magic and religion, and healing the entire body and soul, rather than focusing on a few symptoms like modern medicine. Early medicine often included the use of herbs and meditation. Based on archaeological evidence, some prehistoric practitioners in both Europe and South America used trephining, making a hole in the skull to release illness. Severe diseases were often thought of as supernatural

or magical. The result of the introduction of Eurasian diseases to the

Americas was that many more native peoples were killed by disease and germs

than by the colonists' use of guns or other weapons. Scholars estimate

that over a period of four centuries, epidemic diseases wiped out as

much as 90 percent of the American indigenous populations.

In Europe during the age of exploration, diseases such as smallpox, measles and tuberculosis

(TB) had already been introduced centuries before through trade with

Asia and Africa. People had developed some antibodies to these and other

diseases from the Eurasian continent. When the Europeans traveled to

new lands, they carried these diseases with them. (Note: Scholars

believe TB was already endemic in the Americas.) When such diseases were

introduced for the first time to new populations of humans, the effects

on the native populations were widespread and deadly. The Columbian Exchange, referring to Christopher Columbus's first contact with the native peoples of the Caribbean, began the trade of animals, and plants, and unwittingly began an exchange of diseases.

It was not until the 1800s that humans began to recognize the existence and role of germs and microbes in relation to disease. Although many thinkers had ideas about germs, it was not until Louis Pasteur spread his theory about germs, and the need for washing hands and maintaining sanitation

(particularly in medical practice), that anyone listened. Many people

were quite skeptical, but on May 22, 1881 Pasteur persuasively

demonstrated the validity of his germ theory of disease with an early

example of vaccination. The anthrax vaccine was administered to 25 sheep while another 25 were used as a control. On May 31, 1881 all of the sheep were exposed to anthrax. While every sheep in the control group died, each of the vaccinated sheep survived.

Pasteur's experiment would become a milestone in disease prevention.

His findings, in conjunction with other vaccines that followed, changed

the way globalization affected the world.

Effects of globalization on disease in the modern world

Modern modes of transportation allow more people and products to travel around the world at a faster pace; they also open the airways to the transcontinental movement of infectious disease vectors. One example is the West Nile virus. It is believed that this disease reached the United States via “mosquitoes that crossed the ocean by riding in airplane wheel wells and arrived in New York City in 1999.”

With the use of air travel, people are able to go to foreign lands,

contract a disease and not have any symptoms of illness until after they

get home, and having exposed others to the disease along the way.

As medicine has progressed, many vaccines and cures have been

developed for some of the worst diseases (plague, syphilis, typhus,

cholera, malaria) which people suffer. But, because the evolution of disease organisms is very rapid, even with vaccines, there is difficulty providing full immunity

to many diseases. Finding vaccines at all for some diseases remains

extremely difficult. Without vaccines, the global world remains

vulnerable to infectious diseases.

Evolution of disease presents a major threat in modern times. For example, the current "swine flu" or H1N1 virus

is a new strain of an old form of flu, known for centuries as Asian flu

based on its origin on that continent. From 1918–1920, a post-World War I global influenza epidemic killed an estimated 50–100 million people, including half a million in the United States alone. H1N1 is a virus that has evolved from and partially combined with portions of avian, swine, and human flu.

Globalization has increased the spread of infectious diseases

from South to North, but also the risk of non-communicable diseases by

transmission of culture and behavior from North to South. It is

important to target and reduce the spread of infectious diseases in

developing countries. However, addressing the risk factors of

non-comunicable diseases and lifestyle risks in the South that cause

disease, such as use or consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy

foods, is important as well.

Specific diseases

Plague

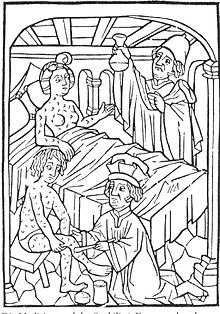

Contemporary engraving of Naples during the Naples Plague in 1656

Bubonic plague is a variant of the deadly flea-borne disease plague, which is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis,

that devastated human populations beginning in the 14th century.

Bubonic plague is primarily spread by fleas that lived on the black rat,

an animal that originated in south Asia and spread to Europe by the 6th

century. It became common to cities and villages, traveling by ship

with explorers. A human would become infected after being bitten by an

infected flea. The first sign of an infection of bubonic plague is

swelling of the lymph nodes, and the formation of buboes. These buboes would first appear in the groin or armpit area, and would often ooze pus or blood.

Eventually infected individuals would become covered with dark

splotches caused by bleeding under the skin. The symptoms would be

accompanied by a high fever, and within four to seven days of infection, more than half the victims would die.

The first recorded outbreak of plague occurred in China

in the 1330s, a time when China was engaged in substantial trade with

western Asia and Europe. The plague reached Europe in October 1347. It

was thought to have been brought into Europe through the port of Messina, Sicily, by a fleet of Genoese trading ships from Kaffa, a seaport on the Crimean peninsula.

When the ship left port in Kaffa, many of the inhabitants of the town

were dying, and the crew was in a hurry to leave. By the time the fleet

reached Messina, all the crew were either dead or dying; the rats that

took passage with the ship slipped unnoticed to shore and carried the

disease with them and their fleas.

Within Europe, the plague struck port cities first, then followed people along both sea and land trade routes. It raged through Italy into France and the British Isles. It was carried over the Alps into Switzerland, and eastward into Hungary and Russia. For a time during the 14th and 15th centuries, the plague would recede. Every ten to twenty years, it would return. Later epidemics, however, were never as widespread as the earlier outbreaks, when 60% of the population died.

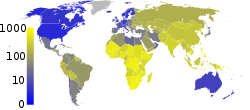

Worldwide distribution of plague-infected animals, 1998

The third plague pandemic emerged in Yunnan

province of China in the mid-nineteenth century. It spread east and

south through China, reaching Guangzhou (Canton) and the British

colonial port of Hong Kong

in 1894, where it entered the global maritime trade routes. Plague

reached Singapore and Bombay in 1896. China lost an estimated 2 million

people between plague's reappearance in the mid-nineteenth century and

its retreat in the mid-twentieth. In India, between 1896 the 1920s,

plague claimed an estimated 12 million lives, most in the Bombay

province. Plague spread into the countries around the Indian Ocean, the

Red Sea and the Mediterranean. From China it also spread eastward to

Japan, the Philippines and Hawaii, and in Central Asia it spread

overland into the Russian territories from Siberia to Turkistan. By

1901 there had been outbreaks of plague on every continent, and new

plague reservoirs would produce regular outbreaks over the ensuing

decades.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious airborne virus

spread by contact with infected oral and nasal fluids. When a person

with measles coughs or sneezes, he releases microscopic particles into

the air. During the 4- to 12-day incubation period,

an infected individual shows no symptoms, but as the disease

progresses, the following symptoms appear: runny nose, cough, red eyes,

extremely high fever and a rash.

Measles is an endemic disease,

meaning that it has been continually present in a community, and many

people developed resistance. In populations that have not been exposed

to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a

measles outbreak in Cuba

killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox.

Two years later measles was responsible for the deaths of half the

indigenous population of Honduras, and ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.

Historically, measles was very prevalent throughout the world, as

it is highly contagious. According to the National Immunization

Program, 90% of people were infected with measles by age 15, acquiring

immunity to further outbreaks. Until a vaccine was developed in 1963,

measles was considered to be deadlier than smallpox.

Vaccination reduced the number of reported occurrences by 98%. Major

epidemics have predominantly occurred in unvaccinated populations,

particularly among nonwhite Hispanic and African American children under 5 years old.

In 2000 a group of experts determined that measles was no longer

endemic in the United States. The majority of cases that occur are among

immigrants from other countries.

Typhus

Typhus is caused by rickettsia, which is transmitted to humans through lice. The main vector for typhus is the rat flea.

Flea bites and infected flea feaces in the respiratory tract are the

two most common methods of transmission. In areas where rats are not

common, typhus may also be transmitted through cat and opossum fleas. The incubation period of typhus is 7–14 days. The symptoms start with a fever, then headache, rash, and eventually stupor. Spontaneous recovery occurs in 80–90% of victims.

The first outbreak of typhus was recorded in 1489. Historians believe that troops from the Balkans, hired by the Spanish army, brought it to Spain with them. By 1490 typhus traveled from the eastern Mediterranean into Spain and Italy, and by 1494, it had swept across Europe. From 1500–1914, more soldiers were killed by typhus than from all the combined military actions during that time. It was a disease associated with the crowded conditions of urban poverty and refugees as well. Finally, during World War I, governments instituted preventative delousing measures among the armed forces and other groups, and the disease began to decline. The creation of antibiotics has allowed disease to be controlled within two days of taking a 200 mg dose of tetracycline.

Syphilis

An early medical illustration of people with syphilis, Vienna, 1498

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease that causes open sores, delirium and rotting skin, and is characterized by genital ulcers. Syphilis can also do damage to the nervous system, brain and heart. The disease can be transmitted from mother to child.

The origins of syphilis are unknown, and some historians argue that it descended from a twenty-thousand-year-old African zoonosis. Other historians place its emergence in the New World, arguing that the crews of Columbus's ships first brought the disease to Europe. The first recorded case of syphilis occurred in Naples in 1495, after King Charles VIII of France besieged the city of Naples, Italy.

The soldiers, and the prostitutes who followed their camps, came from

all corners of Europe. When they went home, they took the disease with

them and spread it across the continent.

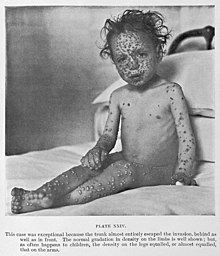

Smallpox

Smallpox is a highly contagious disease caused by the Variola virus.

There are four variations of smallpox; variola major, variola minor,

haemorrhagic, and malignant, with the most common being variola major

and variola minor. Symptoms of the disease including hemorrhaging, blindness, back ache, vomiting, which generally occur shortly after the 12- to 17-day incubation period. The virus begins to attack skin cells, and eventually leads to an eruption of pimples that cover the whole body. As the disease progresses, the pimples

fill up with pus or merge. This merging results in a sheet that can

detach the bottom layer from the top layer of skin. The disease is

easily transmitted through airborne pathways (coughing, sneezing, and

breathing), as well as through contaminated bedding, clothing or other

fabrics.

It is believed that smallpox first emerged over 3000 years ago, probably in India or Egypt. There have been numerous recorded devastating epidemics throughout the world, with high losses of life.

Smallpox was a common disease in Eurasia in the 15th century, and was spread by explorers and invaders. After Columbus landed on the island of Hispaniola during his second voyage in 1493, local people started to die of a virulent infection. Before the smallpox epidemic started, more than one million indigenous people had lived on the island; afterward, only ten thousand had survived.

During the 16th century, Spanish soldiers introduced smallpox by contact with natives of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. A devastating epidemic broke out among the indigenous people, killing thousands.

In 1617, smallpox reached Massachusetts, probably brought by earlier explorers to Nova Scotia, Canada.” By 1638 the disease had broken out among people in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1721 people fled the city after an outbreak, but the residents spread the disease to others throughout the thirteen colonies. Smallpox broke out in six separate epidemics in the United States through 1968.

The smallpox vaccine was developed in 1798 by Edward Jenner. By 1979 the disease had been completely eradicated, with no new outbreaks. The WHO

stopped providing vaccinations and by 1986, vaccination was no longer

necessary to anyone in the world except in the event of future outbreak.

Leprosy

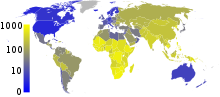

New cases of leprosy in 2016

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s Disease, is caused by a bacillus, Mycobacterium leprae. It is a chronic disease with an incubation period of up to five years. Symptoms often include irritation or erosion of the skin, and effects on the peripheral nerves, mucosa of the upper respiratory tract and eyes. The most common sign of leprosy are pale reddish spots on the skin that lack sensation.

Leprosy originated in India, more than four thousand years ago. It was prevalent in ancient societies in China, Egypt and India, and was transmitted throughout the world by various traveling groups, including Roman Legionnaires, Crusaders, Spanish conquistadors, Asian seafarers, European colonists, and Arab, African, and American slave traders. Some historians believe that Alexander the Great's troops brought leprosy from India to Europe during the 3rd century BC. With the help of the crusaders and other travelers, leprosy reached epidemic proportions by the 13th century.

Once detected, leprosy can be cured using multi-drug therapy,

composed of two or three antibiotics, depending on the type of leprosy.

In 1991 the World Health Assembly began an attempt to eliminate leprosy.

By 2005 116 of 122 countries were reported to be free of leprosy.

Malaria

Past and current malaria prevalence in 2009

On Nov. 6, 1880 Alphonse Laveran discovered that malaria (then called "Marsh Fever") was a protozoan parasite, and that mosquitoes carry and transmit malaria. Malaria is a protozoan infectious disease that is generally transmitted to humans by mosquitoes between dusk and dawn. The European variety, known as "vivax" after the Plasmodium vivax parasite, causes a relatively mild, yet chronically aggravating disease. The west African variety is caused by the sporozoan parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, and results in a severely debilitating and deadly disease.

Malaria was common in parts of the world where it has now

disappeared, as the vast majority of Europe (disease of African descent

are particularly diffused in the Empire romain) and North America . In

some parts of England, mortality due to malaria was comparable to that of sub-Saharan Africa today. Although William Shakespeare was born at the beginning of a colder period called the "Little Ice Age", he knew enough ravages of this disease to include in eight parts. Plasmodium vivax lasted until 1958 in the polders

of Belgium and the Netherlands.

In the 1500s, it was the European settlers and their slaves who probably

brought malaria on the American continent (we know that Columbus was

suffering from this disease before his arrival in the new land). The

Spanish Jesuit missionaries saw the Indians bordering on Lake Loxa Peru used the Cinchona bark powder to treat fevers. However, there is no reference to malaria in the medical literature of the Maya or Aztecs.

The use of the bark of the "fever tree" was introduced into European

medicine by Jesuit missionaries whose Barbabe Cobo who experimented in

1632 and also by exports, which contributed to the precious powder also

being called "Jesuit powder". A study in 2012 of thousands of genetic

markers for Plasmodium falciparum samples confirmed the African origin

of the parasite in South America (Europeans themselves have been

affected by this disease through Africa): it borrowed from the

mid-sixteenth century and the mid-nineteenth the two main roads of the

slave trade, the first leading to the north of South America (Colombia)

by the Spanish, the second most leading south (Brazil) by Portugueses.

Parts of Third World

countries are more affected by malaria than the rest of the world. For

instance, many inhabitants of sub-Saharan Africa are affected by

recurring attacks of malaria throughout their lives. In many areas of Africa, there is limited running water. The residents' use of wells and cisterns provides many sites for the breeding of mosquitoes and spread of the disease. Mosquitoes use areas of standing water like marshes, wetlands, and water drums to breed.

Tuberculosis

In 2007, the prevalence of TB per 100,000 people was highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, and was also relatively high in Asian countries like India.

The bacterium that causes tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is generally spread when an infected person coughs and another person inhales the bacteria. Once inhaled TB frequently grows in the lungs,

but can spread to any part of the body. Although TB is highly

contagious, in most cases the human body is able to fend off the

bacteria. But, TB can remain dormant

in the body for years, and become active unexpectedly. If and when the

disease does become active in the body, it can multiply rapidly, causing

the person to develop many symptoms including cough (sometimes with

blood), night sweats, fever, chest pains, loss of appetite and loss of

weight. This disease can occur in both adults and children and is

especially common among those with weak or undeveloped immune systems.

Tuberculosis (TB) has been one of history's greatest killers,

taking the lives of over 3 million people annually. It has been called

the "white plague". According to the WHO, approximately fifty percent of

people infected with TB today live in Asia. It is the most prevalent, life-threatening infection among AIDS patients. It has increased in areas where HIV seroprevalence is high.

Air travel

and the other methods of travel which have made global interaction

easier, have increased the spread of TB across different societies.

Luckily, the BCG vaccine was developed, which prevents TB meningitis and miliary TB

in childhood. But, the vaccine does not provide substantial protection

against the more virulent forms of TB found among adults. Most forms of

TB can be treated with antibiotics to kill the bacteria. The two

antibiotics most commonly used are rifampicin and isoniazid.

There are dangers, however, of a rise of antibiotic-resistant TB. The

TB treatment regimen is lengthy, and difficult for poor and disorganized

people to complete, increasing resistance of bacteria. Antibiotic-resistant TB is also known as "multidrug-resistant tuberculosis."

"Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis" is a pandemic that is on the rise.

Patients with MDR-TB are mostly young adults who are not infected with

HIV or have other existing illness. Due to the lack of health care

infrastructure in underdeveloped countries, there is a debate as to

whether treating MDR-TB will be cost effective or not. The reason is the

high cost of "second-line" antituberculosis medications. It has been

argued that the reason the cost of treating patients with MDR-TB is high

is because there has been a shift in focus in the medical field, in

particular the rise of AIDS, which is now the world's leading infectious

cause of death. Nonetheless, it is still important to put in the effort

to help and treat patients with "multidrug-resistant tuberculosis" in

poor countries.

HIV/AIDS

Estimated HIV/AIDS prevalence among young adults (15-49) by country as of 2008

HIV and AIDS are among the newest and deadliest diseases. According to the World Health Organization, it is unknown where the HIV virus

originated, but it appeared to move from animals to humans. It may have

been isolated within many groups throughout the world. It is believed

that HIV arose from another, less harmful virus, that mutated and became

more virulent. The first two AIDS/HIV cases were detected in 1981. As

of 2013, an estimated 1.3 million persons in the United States were living with HIV or AIDS, almost 110,000 in the UK and an estimated 35 million people worldwide are living with HIV”.

Despite efforts in numerous countries, awareness and prevention

programs have not been effective enough to reduce the numbers of new HIV

cases in many parts of the world, where it is associated with high

mobility of men, poverty and sexual mores among certain populations.

Uganda has had an effective program, however. Even in countries where

the epidemic has a very high impact, such as Swaziland and South Africa,

a large proportion of the population do not believe they are at risk of

becoming infected. Even in countries such as the UK, there is no

significant decline in certain at-risk communities. 2014 saw the

greatest number of new diagnoses in gay men, the equivalent of nine

being diagnosed a day.

Initially, HIV prevention methods focused primarily on preventing

the sexual transmission of HIV through behaviour change. The ABC

Approach - "Abstinence, Be faithful, Use a Condom". However, by the

mid-2000s, it became evident that effective HIV prevention requires more

than that and that interventions need to take into account underlying

socio-cultural, economic, political, legal and other contextual factors.

Ebola

Cases of Ebola fever in Africa since 1976

The Ebola outbreak, which was the 26th outbreak since 1976, started in Guinea in March 2014. The WHO warned that the number of Ebola patients could rise to 20,000, and said that it used $489m (£294m) to contain Ebola within six to nine months. The outbreak was accelerating. Medecins sans Frontieres has just opened a new Ebola hospital in Monrovia,

and after one week it is already a capacity of 120 patients. It said

that the number of patients seeking treatment at its new Monrovia centre

was increasing faster than they could handle both in terms of the

number of beds and the capacity of the staff, adding that it was

struggling to cope with the caseload in the Liberian capital. Lindis

Hurum, MSF's emergency coordinator in Monrovia, said that it was

humanitarian emergency and they needed a full-scale humanitarian

response. Brice de la Vinge,

MSF director of operations, said that it was not until five months

after the declaration of the Ebola outbreak that serious discussions

started about international leadership and coordination, and said that

it was not acceptable.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis, also known as field fever is an infection caused by Leptospira.

Symptoms can range from none to mild such as headaches, muscle pains,

and fevers; to severe with bleeding from the lungs or meningitis. Leptospira

is transmitted by both wild and domestic animals, most commonly by

rodents. It is often transmitted by animal urine or by water or soil

containing animal urine coming into contact with breaks in the skin,

eyes, mouth, or nose.

The countries with the highest reported incidence are located in the

Asia-Pacific region (Seychelles, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand) with

incidence rates over 10 per 1000,000 people s well as in Latin America

and the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Jamaica, El Salvador,

Uruguay, Cuba, Nicaragua and Costa Rica) However, the rise in global travel and eco-tourism has led to dramatic changes in the epidemiology of leptospirosis, and

travelers from around the world have become exposed to the threat of

leptospirosis. Despite decreasing prevalence of leptospirosis in endemic

regions, previously non-endemic countries are now reporting increasing

numbers of cases due to recreational exposure International travelers engaged in adventure sports are directly

exposed to numerous infectious agents in the environment and now

comprise a growing proportion of cases worldwide.

Disease X

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the name Disease X in 2018 to focus on preparations and predictions of a major pandemic.

COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) worldwide crisis

Coronavirus disease 2019, abbreviated COVID-19, is a disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, and first appeared in Wuhan, China in December 2019, after generic predictions and preparations had been made and dismantled Template:Made and dismantled by who? during the previous decades.

COVID-19 was first reported as a pneumonia outbreak by the Chinese

government. By December 31, 2019, the disease was confirmed to be a

novel strain of coronavirus, which was labeled 2019-nCoV (later changed

to SARS-CoV-2). The first death from this new strain of coronavirus was

reported by the Chinese government in January 11, 2020. By January 13, the first case of COVID-19 was reported outside of China. Nearly 200 countries have reported cases since then, with about 1.68 million confirmed cases worldwide as of April 10, 2020.

Due to a lack of testing resources, the actual number of cases of the

virus are unknown. Symptoms include: fever, coughing, shortness of

breath, and may develop to bluish lips and face, confusion, persistent

chest pain or pressure, and other flu-like symptoms.

Non-communicable disease

Globalization can benefit people with non-communicable diseases such as heart problems or mental health problems. Global trade and rules set forth by the World Trade Organization

can actually benefit the health of people by making their incomes

higher, allowing them to afford better health care. While it has to be

admitted making many non-communicable diseases more likely as well. Also

the national income of a country, mostly obtained by trading on the

global market, is important because it dictates how much a government

spends on health care for its citizens. It also has to be acknowledged

that an expansion in the definition of disease often accompanies

development, so the net effect is not clearly beneficial due to this and

other effects of increased affluence. Metabolic syndrome is one obvious

example. Although poorer countries have not yet experienced this and

are still suffering from diseases listed above.