| Translations of Prajñāpāramitā | |

|---|---|

| English | Perfection of Transcendent Wisdom |

| Sanskrit | प्रज्ञापारमिता (IAST: Prajñāpāramitā) |

| Burmese | ပညာပါရမီတ (IPA: [pjɪ̀ɰ̃ɲà pàɹəmìta̰]) |

| Chinese | 般若波羅蜜多 (Pinyin: bōrě bōluómìduō) |

| Japanese | 般若波羅蜜多 (rōmaji: hannya-haramitta) |

| Khmer | ប្រាជ្ញាបារមីតា (prach-nha-barameida) |

| Korean | 반야바라밀다 (RR: Banyabaramilda) |

| Mongolian | Төгөлдөр билгүүн |

| Sinhala | ප්රඥාව |

| Tibetan | ་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པ་ (shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa) |

| Thai | ปรัชญาปารมิตา |

| Vietnamese | Bát-nhã-ba-la-mật-đa |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Prajñāpāramitā means "the Perfection of (Transcendent) Wisdom" in Mahāyāna Buddhism. Prajñāpāramitā refers to this perfected way of seeing the nature of reality, as well as to a particular body of sutras and to the personification of the concept in the Bodhisattva known as the "Great Mother" (Tibetan: Yum Chenmo). The word Prajñāpāramitā combines the Sanskrit words prajñā "wisdom" with pāramitā "perfection". Prajñāpāramitā is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism and is generally associated with the doctrine of emptiness (Shunyata) or 'lack of Svabhava' (essence) and the works of Nagarjuna. Its practice and understanding are taken to be indispensable elements of the Bodhisattva path.

According to Edward Conze, the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras are "a collection of about forty texts ... composed somewhere on the Indian subcontinent between approximately 100 BC and AD 600." Some Prajnāpāramitā sūtras are thought to be among the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras.

One of the important features of the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras is anutpada (unborn, no origin).

History

Earliest texts

Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā

Western scholars have traditionally considered the earliest sūtra in the Prajñāpāramitā class to be the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra or "Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Lines", which was probably put in writing in the 1st century BCE. This chronology is based on the views of Edward Conze, who largely considered dates of translation into other languages. This text also has a corresponding version in verse format, called the Ratnaguṇasaṃcaya Gāthā, which some believe to be slightly older because it is not written in standard literary Sanskrit. However, these findings rely on late-dating Indian texts, in which verses and mantras are often kept in more archaic forms.

Additionally, a number of scholars have proposed that the Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā teachings were first developed by the Caitika subsect of the Mahāsāṃghikas. They believe that the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra originated amongst the southern Mahāsāṃghika schools of the Āndhra region, along the Kṛṣṇa River. These Mahāsāṃghikas had two famous monasteries near Amarāvati and the Dhānyakataka, which gave their names to the Pūrvaśaila and Aparaśaila schools. Each of these schools had a copy of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra in Prakrit. Guang Xing also assesses the view of the Buddha given in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra as being that of the Mahāsāṃghikas. Edward Conze estimates that this sūtra originated around 100 BCE.

In 2012, Harry Falk and Seishi Karashima published a damaged and partial Kharoṣṭhī manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā. It is radiocarbon dated to ca. 75 CE, making it one of the oldest Buddhist texts in existence. It is very similar to the first Chinese translation of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā by Lokakṣema (ca. 179 CE) whose source text is assumed to be in the Gāndhārī language;Lokakṣema's translation is also the first extant translation of the Prajñāpāramitā genre into a non-Indic language. Comparison with the standard Sanskrit text shows that it is also likely to be a translation from Gāndhāri as it expands on many phrases and provides glosses for words that are not present in the Gāndhārī. This points to the text being composed in Gāndhārī, the language of Gandhara (the region now called the Northwest Frontier of Pakistan, including Peshawar, Taxila and Swat Valley). The "Split" manuscript is evidently a copy of an earlier text, confirming that the text may date before the 1st century CE.

Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā

In contrast to western scholarship, Japanese scholars have traditionally considered the Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) to be from a very early date in the development of Prajñāpāramitā literature. The usual reason for this relative chronology which places the Vajracchedikā earlier is not its date of translation, but rather a comparison of the contents and themes. Some western scholars also believe that the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra was adapted from the earlier Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

Examining the language and phrases used in both the Aṣṭasāhasrikā and the Vajracchedikā, Gregory Schopen also sees the Vajracchedikā as being earlier than the Aṣṭasāhasrikā. This view is taken in part by examining parallels between the two works, in which the Aṣṭasāhasrikā seems to represent the later or more developed position. According to Schopen, these works also show a shift in emphasis from an oral tradition (Vajracchedikā) to a written tradition (Aṣṭasāhasrikā).

Overview of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras

An Indian commentary on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha, entitled Vivṛtaguhyārthapiṇḍavyākhyā, gives a classification of teachings according to the capabilities of the audience:

[A]ccording to disciples' grades, the Dharma is [classified as] inferior and superior. For example, the inferior was taught to the merchants Trapuṣa and Ballika because they were ordinary men; the middle was taught to the group of five because they were at the stage of saints; the eightfold Prajñāpāramitās were taught to bodhisattvas, and [the Prajñāpāramitās] are superior in eliminating conceptually imagined forms. The eightfold [Prajñāpāramitās] are the teachings of the Prajñāpāramitā as follows: the Triśatikā, Pañcaśatikā, Saptaśatikā, Sārdhadvisāhasrikā, Aṣṭasāhasrikā, Aṣṭadaśasāhasrikā, Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā, and Śatasāhasrikā.

The titles of these eight Prajñāpāramitā texts are given according to their length. The texts may have other Sanskrit titles as well, or different variations which may be more descriptive. The lengths specified by the titles are given below.

- Triśatikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 300 lines, alternatively known as the Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (Diamond Sūtra)

- Pañcaśatikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 500 lines

- Saptaśatikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 700 lines, the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī's exposition of Prajñāpāramitā

- Sārdhadvisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 2500 lines, from the questions of Suvikrāntavikrāmin Bodhisattva

- Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 8000 lines

- Aṣṭadaśasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 18,000 lines

- Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 25,000 lines, alternatively known as the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra

- Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra: 100,000 lines, alternatively known as the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra

According to Joseph Walser, there is evidence that the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (25,000 lines) and the Śatasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (100,000 lines) have a connection with the Dharmaguptaka sect, while the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (8000 lines) does not.

In addition to these, there are also other Prajñāpāramitā sūtras such as the Heart Sutra (Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya), which exists in a shorter and longer versions. Regarding the shorter texts, Edward Conze writes, "Two of these, the Diamond Sūtra and the Heart Sūtra are in a class by themselves and deservedly renowned throughout the world of Northern Buddhism. Both have been translated into many languages and have often been commented upon.". Some scholars consider the Diamond Sutra to be much earlier than Conze does. Scholar Jan Nattier argues the Heart Sutra to be an apocryphal text composed in China from extracts of the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā and other texts ca 7th century. Red Pine, however, does not support Nattiers argument and believes the Prajnaparamita Hridaya Sutra to be of Indian origin.

Tāntric versions of the Prajñāpāramitā literature were produced from the year 500 CE on and include sutras such as the Adhyardhaśatikā Prajñāpāramitā (150 lines). Additionally, Prajñāpāramitā terma teachings are held by some Tibetan Buddhists to have been conferred upon Nāgārjuna by the Nāgarāja "King of the Nāgas", who had been guarding them at the bottom of the sea.

Commentaries and translations

There are various Indian and later Chinese commentaries on the Prajñāpāramitā sutras, some of the most influential commentaries include:

- Mahāprajñāpāramitāupadeśa (大智度論, T no. 1509) a massive and encyclopedic text translated into Chinese by the Buddhist scholar Kumārajīva (344–413 CE). It is a commentary on the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā. This text claims to be from the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna (c. 2nd century) in the colophon, but various scholars such as Étienne Lamotte have questioned this attribution. This work was translated by Lamotte as Le Traité de la Grande Vertu de Sagesse and into English from the French by Gelongma Karma Migme Chodron.

- Abhisamayālaṅkāra (Ornament of clear realization), the central Prajñāpāramitā shastra in the Tibetan tradition. It is traditionally attributed as a revelation from the Bodhisattva Maitreya to the scholar Asanga (fl. 4th century C.E.), known as a master of the Yogachara school. The Indian commentary on this text by Haribadra, the Abhisamayalankaraloka, has also been influential on later Tibetan texts.

- Śatasāhasrikā-pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikāṣṭādaśasāhasrikā-prajñāpāramitā-bṛhaṭṭīkā, often attributed to Vasubandhu (4th century).

- Satasahasrika-paramita-brhattika, attributed to Daṃṣṭrāsena.

- Dignāga's Prajnaparamitarthasamgraha-karika.

- Ratnākaraśānti's Prajñāpāramitopadeśa.

The sutras were first brought to Tibet in the reign of Trisong Detsen (742-796) by scholars Jinamitra and Silendrabodhi and the translator Ye shes sDe.

Prajñāpāramitā in Central Asia

By the middle of the 3rd century CE, it appears that some Prajñāpāramitā texts were known in Central Asia, as reported by the Chinese monk Zhu Shixing, who brought back a manuscript of the Prajñāpāramitā of 25,000 lines:

When in 260 AD, the Chinese monk Zhu Shixing chose to go to Khotan in an attempt to find original Sanskrit sūtras, he succeeded in locating the Sanskrit Prajñāpāramitā in 25,000 verses, and tried to send it to China. In Khotan, however, there were numerous Hīnayānists who attempted to prevent it because they regarded the text as heterodox. Eventually, Zhu Shixing stayed in Khotan, but sent the manuscript to Luoyang where it was translated by a Khotanese monk named Mokṣala. In 296, the Khotanese monk Gītamitra came to Chang'an with another copy of the same text.

China

In China, there was extensive translation of many Prajñāpāramitā texts beginning in the second century CE. The main translators include: Lokakṣema (支婁迦讖), Zhī Qīan (支謙), Dharmarakṣa (竺法護), Mokṣala (無叉羅), Kumārajīva (鳩摩羅什, 408 CE), Xuánzàng (玄奘), Făxián (法賢) and Dānapāla (施護). These translations were very influential in the development of East Asian Mādhyamaka and on Chinese Buddhism.

Xuanzang (fl. c. 602–664) was a Chinese scholar who traveled to India and returned to China with three copies of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra which he had secured from his extensive travels. Xuanzang, with a team of disciple translators, commenced translating the voluminous work in 660 CE using the three versions to ensure the integrity of the source documentation. Xuanzang was being encouraged by a number of the disciple translators to render an abridged version. After a suite of dreams quickened his decision, Xuanzang determined to render an unabridged, complete volume, faithful to the original of 600 fascicles.

There are also later commentaries from Zen Buddhists on the Heart and Diamond sutra and Kūkai's commentary (9th century) is the first known Tantric commentary.

Themes in Prajñāpāramitā sutras

Core themes

The Bodhisattva and Prajñāpāramitā

A key theme of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras is the figure of the Bodhisattva (literally: awakening-being) which is defined in the 8,000 line Prajñāpāramitā sutra as:

- "One who trains in all dharmas [phenomena] without obstruction [asakti, asaktatā], and also knows all dharmas as they really are."

A Bodhisattva is then a being that experiences everything "without attachment" (asakti) and sees reality or suchness (Tathātā) as it is. The Bodhisattva is the main ideal in Mahayana (Great Vehicle), which sees the goal of the Buddhist path as becoming a Buddha for the sake of all sentient beings, not just yourself:

- They make up their minds that ‘one single self we shall tame . . . one single self we shall lead to final Nirvana.’

- A Bodhisattva should certainly not in such a way train himself.

- On the contrary, he should train himself thus: "My own self I will place in Suchness [the true way of things], and, so that all the world might be helped,

- I will place all beings into Suchness, and I will lead to Nirvana the whole immeasurable world of beings."

A central quality of the Bodhisattva is their practice of Prajñāpāramitā, a most deep (gambhīra) state of knowledge which is an understanding of reality arising from analysis as well as meditative insight. It is non-conceptual and non-dual (advaya) as well as transcendental. Literally, the term could be translated as "knowledge gone to the other (shore)", or transcendental knowledge. The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra says:

- This is known as the Prajñāpāramitā of the bodhisattvas; not grasping at form, not grasping at sensation, perception, volitions and cognition.

A further passage in the 8,000 line Prajñāpāramitā sutra states that Prajñāpāramitā means that a Bodhisattva stands in emptiness (shunyata) by not standing (√sthā) or supporting themselves on any dharma (phenomena), whether conditioned or unconditioned. The dharmas that a Bodhisattva does "not stand" on include standard listings such as: the five aggregates, the sense fields (ayatana), nirvana, Buddhahood, etc. This is explained by stating that Bodhisattvas "wander without a home" (aniketacārī); "home" or "abode" meaning signs (nimitta, meaning a subjective mental impression) of sensory objects and the afflictions that arise dependent on them. This includes the absence, the "not taking up" (aparigṛhīta) of even "correct" mental signs and perceptions such as "form is not self", "I practice Prajñāpāramitā", etc. To be freed of all constructions and signs, to be signless (animitta) is to be empty of them and this is to stand in Prajñāpāramitā. The Prajñāpāramitā sutras state that all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in the past have practiced Prajñāpāramitā. Prajñāpāramitā is also associated with Sarvajñata (all-knowledge) in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras, a quality of the mind of a Buddha which knows the nature of all dharmas.

According to Karl Brunnholzl, Prajñāpāramitā means that "all phenomena from form up through omniscience being utterly devoid of any intrinsic characteristics or nature of their own." Furthermore, "such omniscient wisdom is always nonconceptual and free from reference points since it is the constant and panoramic awareness of the nature of all phenomena and does not involve any shift between meditative equipoise and subsequent attainment."

Edward Conze outlined several psychological qualities of a Bodhisattva's practice of Prajñāpāramitā:

- Non-apprehension (anupalabdhi)

- No settling down or "non-attachment" (anabhinivesa)

- No attainment (aprapti). No person can "have," or "possess," or "acquire," or "gain" any dharma.

- Non-reliance on any dharma, being unsupported, not leaning on any dharma.

- "Finally, one may say that the attitude of the perfected sage is one of non-assertion."

Other Bodhisattva qualities

The Prajñāpāramitā sutras also teach of the importance of the other paramitas (perfections) for the Bodhisattva such as Ksanti (patience): "Without resort to this patience (kṣānti) they [bodhisattvas] cannot reach their respective goals".

Another quality of the Bodhisattva is their freedom from fear (na √tras) in the face of the seemingly shocking doctrine of the emptiness of all dharmas which includes their own existence. A good friend (kalyanamitra) is useful in the path to fearlessness. Bodhisattvas also have no pride or self-conception (na manyeta) of their own stature as Bodhisattvas. These are important features of the mind of a bodhisattva, called bodhicitta. The Prajñāpāramitā sutras also mention that bodhicitta is a middle way, it is neither apprehended as existent (astitā) or non-existent (nāstitā) and it is "immutable" (avikāra) and "free from conceptualization" (avikalpa).

The Bodhisattva is said to generate "great compassion" (maha-karuṇā) for all beings on their path to liberation and yet also maintain a sense of equanimity (upekṣā) and distance from them through their understanding of emptiness, due to which, the Bodhisattva knows that even after bringing countless beings to nirvana, "no living being whatsoever has been brought to nirvana." Bodhisattvas and Mahāsattvas are also willing to give up all of their meritorious deeds for sentient beings and develop skillful means (upaya) in order to help abandon false views and teach them the Dharma. The practice of Prajñāpāramitā allows a Bodhisattva to become:

"a saviour of the helpless, a defender of the defenceless, a refuge to those without refuge, a place to rest to those without resting place, the final relief of those who are without it, an island to those without one, a light to the blind, a guide to the guideless, a resort to those without one and....guide to the path those who have lost it, and you shall become a support to those who are without support."

Tathātā

Tathātā (Suchness or Thusness) and the related term Dharmatā (the nature of Dharma), and Tathāgata are also important terms of the Prajñāpāramitā texts. To practice Prajñāpāramitā means to practice in accord with 'the nature of Dharma' and to see the Tathāgata (i.e. the Buddha). As the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra states, these terms are generally used equivalently: "As the suchness (tathatā) of dharmas is immovable (acalitā), and the suchness (tathatā) of dharmas is the Tathāgata.". The Tathāgata is said in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra to "neither come nor go". Furthermore, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra includes a list of synonyms associated with Tathāgata as also being "beyond coming and going", these include: 1. Suchness (tathatā); 2. Unarisen (anutpāda); 3. Reality limit (bhūtakoṭi); 4. Śūnyatā; 5. Division (yathāvatta); 6. Detachment (virāga); 7. Cessation (nirodha); 8. Space element (ākāśadhātu). The sutra then states:

Apart from these dharmas, there is no Tathāgata. The suchness of these dharmas, and the suchness of the Tathāgatas, is all one single suchness (ekaivaiṣā tathatā), not two, not divided (dvaidhīkāraḥ). … beyond all classification (gaṇanāvyativṛttā), due to non-existence (asattvāt).

Suchness then does not come or go because like the other terms, it is not a real entity (bhūta, svabhāva), but merely appears conceptually through dependent origination, like a dream or an illusion.

Edward Conze lists six ways in which the ontological status of dharmas is considered by the Prajñāpāramitā:

- Dharmas are non-existent because they have no own-being (svabhava).

- Dharmas have a purely nominal existence. They are mere words, a matter of conventional expression.

- Dharmas are "without marks, with one mark only, ie., with no mark." A mark (laksana) being a distinctive property which separates it from other dharmas.

- Dharmas are isolated (vivikta), absolutely isolated (atyantavivikta).

- Dharmas have never been produced, never come into existence; they are not really ever brought forth, they are unborn (ajata).

- Non-production is illustrated by a number of similes, i.e., dreams, magical illusions, echoes, reflected images, mirages, and space.

It is through seeing this Tathātā that one is said to have a vision of the Buddha (the Tathāgata), seeing this is called seeing the Buddha's Dharmakaya (Dharma body) which is a not his physical body, but none other than the true nature of dharmas.

Negation and Emptiness

Most modern Buddhist scholars such as Lamotte, Conze and Yin Shun have seen Śūnyatā (emptiness, voidness, hollowness) as the central theme of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. Edward Conze writes:

It is now the principal teaching of Prajñāpāramitā with regard to own-being that it is "empty." The Sanskrit term is svabhāva-śūnya. This is a tatpuruṣa compound (one in which the last member is qualified by the first without losing its grammatical independence), in which svabhava may have the sense of any oblique case. The Mahayana understands it to mean that dharmas are empty of any own-being, i.e.,that they are not ultimate facts in their own right, but merely imagined and falsely discriminated, for each and every one of them is dependent on something other than itself. From a slightly different angle this means that dharmas, when viewed with perfected gnosis, reveal an own-being which is identical with emptiness, i.e in their own-being they are empty.

The Prajñāpāramitā sutras commonly use apophatic statements to express the nature of reality as seen by Prajñāpāramitā. A common trope in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras is the negation of a previous statement in the form 'A is not A, therefore it is A', or more often negating only a part of the statement as in, “XY is a Y-less XY”. Japanese Buddhologist, Hajime Nakamura, calls this negation the 'logic of not' (na prthak). An example from the Diamond sutra of this use of negation is:

- As far as ‘all dharmas’ are concerned, Subhuti, all of them are dharma-less. That is why they are called ‘all dharmas.’

The rationale behind this form is the juxtaposition of conventional truth with ultimate truth as taught in the Buddhist two truths doctrine. The negation of conventional truth is supposed to expound the ultimate truth of the emptiness (Śūnyatā) of all reality - the idea that nothing has an ontological essence and all things are merely conceptual, without substance.

The Prajñāpāramitā sutras state that dharmas should not be conceptualized either as existent, nor as non existent, and use negation to highlight this: "in the way in which dharmas exist (saṃvidyante), just so do they not exist (asaṃvidyante)".

Māyā

The Prajñāpāramitā sutras commonly state that all dharmas (phenomena), are in some way like an illusion (māyā), like a dream (svapna) and like a mirage. The Diamond Sutra states:

- "A shooting star, a clouding of the sight, a lamp, An illusion, a drop of dew, a bubble, A dream, a lightning’s flash, a thunder cloud— This is the way one should see the conditioned."

Even the highest Buddhist goals like Buddhahood and Nirvana are to be seen in this way, thus the highest wisdom or prajña is a type of spiritual knowledge which sees all things as illusory. As Subhuti in the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra states:

- "Even if perchance there could be anything more distinguished, of that also I would say that it is like an illusion, like a dream. For not two different things are illusions and Nirvāṇa, are dreams and Nirvāṇa."

This is connected to the impermanence and insubstantial nature of dharmas. The Prajñāpāramitā sutras give the simile of a magician (māyākāra: 'illusion-maker') who, when seemingly killing his illusory persons by cutting off their heads, really kills nobody and compare it to the bringing of beings to awakening (by 'cutting off' the conceptualization of self view; Skt: ātmadṛṣṭi chindati) and the fact that this is also ultimately like an illusion, because their aggregates "are neither bound nor released". The illusion then, is the conceptualization and mental fabrication of dharmas as existing or not existing, as arising or not arising. Prajñāpāramitā sees through this illusion, being empty of concepts and fabrications.

Perceiving dharmas and beings like an illusion (māyādharmatā) is termed the "great armor" (mahāsaṃnaha) of the Bodhisattva, who is also termed the 'illusory man' (māyāpuruṣa).

Later additions

According to Paul Williams, another major theme of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras is "the phenomenon of laudatory self reference – the lengthy praise of the sutra itself, the immense merits to be obtained from treating even a verse of it with reverence, and the nasty penalties which will accrue in accordance with karma to those who denigrate the scripture."

According to Edward Conze, the Prajñāpāramitā sutras added much new doctrinal material in the later layers and the larger texts. Conze lists the later accretions as:

- Increasing sectarianism, with all the rancor, invective and polemics that that implies

- Increasing scholasticism and the insertion of longer and longer Abhidharma lists

- Growing stress on skill in means, and on its subsidiaries such as the Bodhisattva's Vow and the four means of conversion, and its logical sequences, such as the distinction between provisional and ultimate truth

- A growing concern with the Buddhist of faith, with its celestial Buddhas and Bodhisattva and their Buddha-fields;

- A tendency towards verbosity, repetitiveness and overelaboration

- Lamentations over the decline of the Dharma

- Expositions of the hidden meaning which become the more frequent the more the original meaning becomes obscured

- Any reference to the Dharma body of the Buddha as anything different from a term for the collection of his teachings

- A more and more detailed doctrine of the graded stages (bhumi) of a Bodhisattva's career.

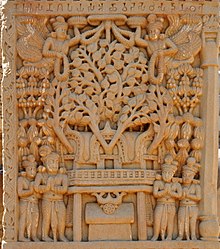

Prajñāpāramitā in visual art

The Prajnaparamita is often personified as a bodhisattvadevi (female bodhisattva). Artifacts from Nalanda depict the Prajnaparamita personified as a deity. The depiction of Prajnaparamita as a Yidam deity can also be found in ancient Java and Cambodian art.

Prajñāpāramitā in Ancient Indonesia

Mahayana Buddhism took root in ancient Java Sailendra court in the 8th century CE. The Mahayana reverence of female buddhist deity started with the cult of Tara enshrined in the 8th century Kalasan temple in Central Java. Some of Prajnaparamita's important functions and attributes can be traced to those of the goddess Tara. Tara and Prajnaparamita are both referred to as mothers of all Buddhas, since Buddhas are born from wisdom. The Sailendra dynasty was also the ruling family of Srivijaya in Sumatra. During the reign of the third Pala king Devapala (815-854) in India, Srivijaya Maharaja Balaputra of Sailendras also constructed one of Nalanda's main monasteries in India itself. Thereafter manuscript editions of the Ashtasahasrika Prajnaparamita Sutra circulating in Sumatra and Java instigated the cult of the Goddess of Transcendent Wisdom.

In the 13th century, the tantric buddhism gained royal patronage of king Kertanegara of Singhasari, and thereafter some of Prajnaparamita statues were produced in the region, such as the Prajnaparamita of Singhasari in East Java and Prajnaparamita of Muaro Jambi Regency, Sumatra. Both of East Java and Jambi Prajnaparamitas bear resemblance in style as they were produced in same period, however unfortunately Prajnaparamita of Jambi is headless and was discovered in poor condition.

The statue of Prajnaparamita of East Java is probably the most famous depiction of the goddess of transcendental wisdom, and is considered the masterpiece of classical ancient Java Hindu-Buddhist art in Indonesia. It was discovered in the Cungkup Putri ruins near Singhasari temple, Malang, East Java. Today the beautiful and serene statue is displayed on 2nd floor Gedung Arca, National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta.