| Postpartum psychosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | puerperal psychosis |

| |

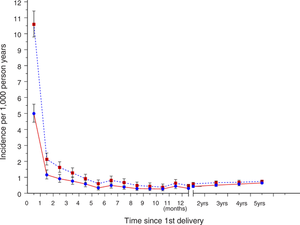

| Rates of psychoses among Swedish first-time mothers | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Hallucinations, delusions, mood swings, confusion, restlessness, personality changes |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental |

| Risk factors | Family history, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, difficult pregnancy |

| Treatment | Anti-psychotics, mood stabilizers , anti-depressants |

Early in the history of medicine, it was recognized that severe mental illness sometimes started abruptly in the days after childbirth, later known as puerperal or postpartum psychosis. Gradually, it became clear that this was not a single and unique entity, but a group of at least twenty distinct disorders.

Psychosis implies the presence of manic symptoms, stupor or catatonia, perplexity, confusion, disorders of the will and self, delusions and/ or hallucinations. Psychiatric disorders that lack these symptoms are excluded; depression, however severe, is not included, unless there are psychotic features.

Of this group of psychoses, postpartum bipolar disorder is overwhelmingly the most common in high-income nations.

Postpartum Bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms

Almost every symptom known to psychiatry occurs in these mothers – every kind of delusion including the rare delusional parasitosis, delusional misidentification syndrome, Cotard delusion, erotomania, and the changeling delusion, denial of pregnancy or birth, command hallucinations, disorders of the will and self, catalepsy and other symptoms of catatonia, self-mutilation and all the severe disturbances of mood. In addition, the literature also describes symptoms not generally recognized, such as rhyming speech, enhanced intellect, and enhanced perception.

As for collections of symptoms (syndromes), about 40% have puerperal mania, with increased vitality and sociability, reduced need for sleep, rapid thinking and pressured speech, euphoria and irritability, loss of inhibition, violence, recklessness and grandiosity (including religious and expansive delusions); puerperal mania is considered to be particularly severe, with highly disorganized speech, extreme excitement and eroticism.

Another 25% have an acute polymorphic (cycloid) syndrome. This is a changing clinical state, with transient delusions, fragments of other syndromes, extreme fear or ecstasy, perplexity, confusion and motility disturbances. In the past some experts regarded this as pathognomonic (specific) for puerperal psychosis, but this syndrome is found in other settings, not just the reproductive process, and in men. These psychoses are placed in the World Health Organization's ICD-10 under the rubric of acute and transient psychotic disorders. In general psychiatry, manic and cycloid syndromes are regarded as distinct, but, studied long-term among childbearing women, the bipolar and cycloid variants are intermingled in a bewildering variety of combinations, and, in this context, it seems best to regard them as members of the same ‘bipolar/cycloid’ group. Together the manic and cycloid variants make up about two thirds of childbearing psychoses.

Diagnosis

Postpartum bipolar disorders must be distinguished from a long list of organic psychoses that can present in the puerperium, and from other non-organic psychoses; both of these groups are described below. It is also necessary to distinguish them from other psychiatric disorders associated with childbirth, such as anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, complaining disorders and bonding disorders (emotional rejection of the infant), which occasionally cause diagnostic difficulties.

Clinical assessment requires obtaining the history from the mother herself and, because she is often severely ill, lacking in insight and unable to give a clear account of events, from at least one close relative. A social work report and, in mothers admitted to hospital, nursing observations are information sources of great value. A physical examination and laboratory investigations may disclose somatic illness complicating the obstetric events, which sometimes provokes psychosis. It is important to obtain the case records of previous episodes of mental illness, and, in patients with multiple episodes, to construct a summary of the whole course of her psychiatric history in relation to her life.

In the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases, published in 1992, the recommendation is to classify these cases by the form of the illness, without highlighting the postpartum state. There is, however, a category F53.1, entitled 'severe mental and behavioural disorders associated with the puerperium', which can be used when it is not possible to diagnose some variety of affective disorder or schizophrenia. The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, whose 5th edition was published in May 2013, allows the use of a 'peripartum onset specifier' in episodes of mania, hypomania or major depression if the symptoms occur during pregnancy or the first four weeks of the puerperium. The failure to recognize postpartum psychosis, and its complexity, is unhelpful to clinicians, epidemiologists, and other researchers.

Onset groups

Postpartum bipolar disease belongs to the bipolar spectrum, whose disorders exist in two contrasting forms – mania and depression. They are highly heritable, and sufferers (rather less than 1% of the population) have a lifelong tendency (diathesis) to develop psychotic episodes in certain circumstances. The ‘triggers’ include a number of pharmaceutical agents, surgical operations, adrenal corticosteroids, seasonal changes, menstruation and childbearing. Research into puerperal mania is, therefore, not the study of a ‘disease-in-its-own right’, but an investigation into the childbearing triggers of bipolar disorder.

Psychoses triggered in the first two weeks after the birth - between the first postpartum day (or even during parturition until about the 15th day – complicate approximately 1/1,000 pregnancies. The impression is sometimes given that this is the only trigger associated with childbearing. But there is evidence of four other triggers – late postpartum, prepartum, post-abortion and weaning. Marcé, widely considered an authority on puerperal psychoses , claimed that they could be divided into early and late forms; the late form begins about six weeks after childbirth, associated with the return of the menses . His view is supported by the large number of cases in the literature with onset 4-13 weeks after the birth, mothers with serial 4-13 week onsets and some survey evidence. The evidence for a trigger acting in pregnancy is also based on the large number of reported cases, and particularly on the frequency of mothers suffering two or more prepartum episodes. There is evidence, especially from surveys, of bipolar episodes triggered by abortion (miscarriage or termination). The evidence for a weaning trigger rests on 32 cases in the literature, of which 14 were recurrent. The relative frequency of these five triggers is given by the number of cases in the literature – just over half early postpartum onset, 20% each late postpartum and prepartum onset, and the rest post-abortion and weaning onset.

In addition, episodes starting after childbirth may be triggered by adrenal corticosteroids, surgical operations (such as Caesarean section) or bromocriptine as an alternative to, or in addition to, the postpartum trigger.

Course of the illness

With modern treatment, a full recovery can be expected within 6-10 weeks. After recovery from the psychosis, some mothers suffer from depression, which can last for weeks or months. About one third suffer a relapse, with a return of psychotic symptoms a few weeks after recovery; these relapses are not due to a failure to comply with medication, because they were often described before pharmaceutical treatment was discovered . A minority have a series of periodic relapses related to the menstrual cycle. Complete recovery, with a resumption of normal life and a normal mother-infant relationship is the rule.

Many of these mothers suffer from other bipolar episodes, on the average about one every six years. Although suicide is almost unknown in an acute puerperal manic or cycloid episode, depressive episodes later in life carry an increased risk, and it is wise for mothers to maintain contact with psychiatric services in the long term.

In the event of a further pregnancy, the recurrence rate is high - in the largest series, about three quarters suffered a recurrence, but not always in the early puerperium; the recurrence could occur during pregnancy, or later in the postpartum period. This suggests a link between early onset and other onset groups.

Management, treatment and prevention

Pre-conception counselling

It is known that women with a personal or family history of puerperal psychosis or bipolar disorder are at risk of a puerperal episode. The highest risk of all (82%) is a combination of a previous postpartum episode and at least one earlier non-puerperal episode. There is a need to counsel women at high risk before they embark on pregnancy, especially those on prophylactic treatment. The issues include the teratogenic risk, the frequency of recurrence and the risks and benefit of various treatments during pregnancy and breast-feeding; a personal analysis should be made for each individual, and is best shared with close family members. The teratogenic risks of antipsychotic agents are small, but are higher with lithium and anti-convulsant agents. Carbamazepine, when taken in early pregnancy, has some teratogenic effects, but valproate is associated with spina bifida and other major malformations, and a foetal valproate syndrome; it is contra-indicated in women who may become pregnant. Given late in pregnancy, antipsychotic agents and lithium can have adverse effects on the infant. Stopping mood-stabilisers has a high risk of recurrence during pregnancy.

Pre-birth planning

If a mother at high risk becomes pregnant, it is essential to convene a planning meeting. This is urgent because the diagnosis of pregnancy may be late, and the birth may be premature. The meeting should be attended by primary care, obstetric and psychiatric staff, together (if possible) with the expectant mother and her family and (if appropriate) a social worker. There are many issues – pharmaceutical treatment, antenatal care, early signs of a recurrence, the management of the puerperium, and the care and safety of the infant. It is important that the psychiatric team is notified as soon as the infant is born.

Home treatment and hospitalization

It has been recognized since the 19th century that it is optimal for a mother with puerperal psychosis to be treated at home, where she can maintain her role as homemaker and mother to her other children, and develop her relationship with the new-born. But there are many risks, and it is essential that she is monitored by a competent adult round the clock, and visited frequently by professional staff. Home treatment is a counsel of perfection and most mothers will be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, many as an emergency, and usually without their babies. In a few countries, especially Australia, Belgium, France, India, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, special units allow the admission of both mother and infant. Conjoint admission has many advantages, but the risks to the infant of admission to a ward full of severely ill mothers should not be understated, and the high ratio of nursing staff, required to safeguard the infants, make these among the most expensive psychiatric units.

Treatment of the acute episode

These mothers require sedation with anti-psychotic (neuroleptic) agents, but are liable to extrapyramidal symptoms, including the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Since the link with bipolar disorder was recognized (about 1970), treatment with mood-stabilizing agents, such as lithium and anti-convulsant drugs, has been employed with success. Electroconvulsive therapy has the reputation of efficacy in this disorder, and it can be given during pregnancy (avoiding the risk of pharmaceutical treatment), with due precautions. But there have been no trials, and Dutch experience has shown that almost all mothers recover quickly without it. After recovery the mother may need antidepressant treatment and/or prophylactic mood stabilizers; she will need counselling about the risk of recurrence and will often appreciate psychotherapeutic support.

Prevention

There is much evidence that lithium can at least partly prevent episodes in mothers at high risk. It is dangerous during parturition, when pressure in the pelvis can obstruct the ureters and raise blood levels. Started after the birth its adverse effects are minimal, even in breast-fed infants.

But these are early days in the control of this malady. The ambition of medicine is to eradicate disease through understanding its causes, and dealing with them. To eliminate the risk of puerperal psychosis in the daughters and descendants of present sufferers, we need to know much more about the bipolar diathesis, and how, in each onset group, episodes are triggered.

Causes

The cause of postpartum bipolar disorder breaks down into two parts – the nature of the brain anomalies that predispose to manic and depressive symptoms, and the triggers that provoke these symptoms in those with the bipolar diathesis. The genetic, anatomical and neurochemical basis of bipolar disorder is at present unknown, and is one of the most important projects in psychiatry; but is not the main concern here. The challenge and opportunity presented by the childbearing psychoses is to identify the triggers of early postpartum onset and other onset groups.

Considering that these psychoses have been known for centuries, little effort has so far been made to understand the underlying biology. Research has lagged far behind other areas of medicine and psychiatry. There is a dearth of knowledge and of theories. There is a much evidence of heritability, both from family studies and molecular genetics. Early onset cases occur more frequently in first time mothers, but this is not true of late postpartum or pregnancy onset. There are not many other clues. Sleep deprivation has been suggested. Inhibition of steroid sulphatase caused behavioural abnormalities in mice. A recent hypothesis, supported by collateral studies, invokes the re-awakening of auto-immunity after its suppression during pregnancy, on the model of multiple sclerosis or autoimmune thyroiditis; a related hypothesis has proposed that abnormal immune system processes (regulatory T cell biology) and consequent changes in myelinogenesis may increase postpartum psychosis risk. The other promising lead is based on the similarity of bipolar-cycloid puerperal and menstrual psychosis; many women have suffered from both. Late-onset puerperal psychoses, and relapses may be linked to menstruation. Since almost all reproductive onsets occur when the menstrual cycle is released from a long period of inhibition, this may be a common factor, but it can hardly explain episodes starting in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy.

History

Between the 16th and 18th centuries about 50 brief reports were published; among them is the observation that these psychoses could recur, and that they occur both in breast-feeding and non-lactating women. In 1797, Osiander, an obstetrician from Tübingen, reported two cases at length - masterly descriptions which are among the treasures of medical literature. In 1819, Esquirol conducted a survey of cases admitted to the Salpêtrière, and pioneered long-term studies. From that time, puerperal psychosis became widely known to the medical profession. In the next 200 years over 2,500 theses, articles and books were published. Among the outstanding contributions were Delay's unique investigation using serial curettage and Kendell's record-linkage study comparing 8 trimesters before and 8 trimesters after the birth. In the last few years, two monographs reviewed over 2,400 works, with more than 4,000 cases of childbearing psychoses from the literature and a personal series of more than 320 cases.

Research directions

The lack of a formal diagnosis in the DSM and ICD has hindered research . Research is needed to improve the care and treatment of afflicted mothers, but it is of paramount importance to investigate the causes, because this can lead to long term control and elimination of the disease. The opportunities come under the heading of clinical observation, the study of the acute episode, long-term studies, epidemiology, genetics and neuroscience. If mothers, who have suffered from puerperal psychosis, are concerned to encourage research this is a contact. In a disorder with a strong genetic element and links to the reproductive process, costly imaging, molecular-genetic and neuroendocrinological investigations will be decisive. These depend on expert laboratory methods. It is important that the clinical study is also ‘state-of-the-art’– that scientists understand the complexity of these psychoses, and the need for multiple and reliable information sources to establish the diagnosis.

Other non-organic postpartum psychoses

It is much less common to encounter other acute psychoses in the puerperium.

Psychogenic psychosis

This is the name given to a psychosis whose theme, onset and course are all related to an extremely stressful event. The psychotic symptom is usually a delusion. Over 50 cases have been described, but usually in unusual circumstances, such as abortion. or adoption or in fathers at the time of the birth of one of their children. They are occasionally seen after normal childbirth.

Paranoid and schizophrenic psychoses

These are so uncommon in the puerperium that it seems reasonable to regard them as sporadic events, not puerperal complications.

Early postpartum stupor

Brief states of stupor have rarely been described in the first few hours or days after the birth. They are similar to parturient delirium and stupor, which are among the psychiatric disorders of childbirth.

Organic postpartum psychoses

There are at least a dozen organic (neuropsychiatric) psychoses that can present in pregnancy or soon after childbirth. The clinical picture is usually delirium – a global disturbance of cognition, affecting consciousness, attention, comprehension, perception and memory – but amnesic syndromes and a mania-like state also occur. The two most recent were described in 1980 and 2010, and it is quite likely that others will be described. Organic psychoses, especially those due to infection, may be more common in nations with high parturient morbidity.

Infective delirium

The most common organic postpartum psychosis is infective delirium. This was mentioned by Hippocrates: there are 8 cases of puerperal or post-abortion sepsis among the 17 women in the 1st and 3rd books of epidemics, all complicated by delirium. In Europe and North America the foundation of the metropolitan maternity hospitals, together with instrumental deliveries and the practice of attending necropsies, led to epidemics of streptococcal puerperal fever, resulting in maternal mortality rates up to 10%. The peak was about 1870, after which antisepsis and asepsis gradually brought them under control. These severe infections were often complicated by delirium, but it was not until the nosological advances of Chaslin and Bonhöffer that they could be distinguished from other causes of postpartum psychosis. Infective delirium hardly ever starts during pregnancy, and usually begins in the first postpartum week. The onset of sepsis and delirium are closely related, and the course parallels the infection, although about 20% of patients continue to suffer from chronic confusional states after recovery from the infection. Recurrences after another pregnancy are rare. Their frequency began to decline at the end of the 19th century, and fell steeply after the discovery of the sulphonamides. Puerperal sepsis is still common in Bangladesh, Nigeria and Zambia. Even in Britain, cases are still occasionally seen. It would be a mistake to forget this cause of puerperal psychosis.

Eclamptic and Donkin psychoses

Eclampsia is the sudden eruption of convulsions in a pregnant woman, usually around the time of delivery. It is the late complication of pre-eclamptic toxaemia (gestosis). Although its frequency in nations with excellent obstetric services has fallen below 1/500 pregnancies, it is still common in many other countries. The primary pathology is in the placenta, which secretes an anti-angiogenic factor in response to ischaemia, leading to endothelial dysfunction. In fatal cases, there are arterial lesions in many organs including the brain. This is the second most frequent organic psychosis, and the second to be described. Psychoses occur in about 5% of cases, and about 240 detailed cases have been reported. It particularly affects first time mothers. Seizures may begin before, during or after labour, but the onset of psychosis is almost always postpartum. These mothers usually suffer from delirium but some have manic features. The duration is remarkably short, with a median duration of 8 days. This, together with the absence of a family history and of recurrences, contrasts with puerperal bipolar/cycloid psychoses. After recovery, amnesia and sometimes retrograde memory loss may occur, as well as other permanent cerebral lesions such as dysphasia, hemiplegia or blindness.

A variant was described by Donkin. He had been trained by Simpson (one of those who first recognized the importance of albuminuria) in Edinburgh, and recognized that some cases of eclamptic psychosis occurred without seizures; this explains the interval between seizures (or coma) and psychosis, a gap that has occasionally exceeded 4 days: seizures and psychosis are two different consequences of severe gestosis. Donkin psychosis may not be rare: a British series included 13 possible cases; but clarifying its distinction from postpartum bipolar disorder requires prospective investigations in collaboration with obstetricians.

Wernicke-Korsakoff psychosis

This was described by Wernicke and Korsakoff. The pathology is damage to the core of the brain including the thalamus and mamillary bodies. Its most striking clinical feature is loss of memory, which can be permanent. It is usually found in severe alcoholics, but can also result from pernicious vomiting of pregnancy (hyperemesis gravidarum), because the requirement for thiamine is much increased in pregnancy; nearly 200 cases have been reported. The cause is vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency. This has been available for treatment and prevention since 1936, so the occurrence of this syndrome in pregnancy should be extinct. But these cases continue to be reported – more than 50 in this century – from all over the world, including some from countries with advanced medical services; most are due to rehydration without vitamin supplements. A pregnant woman who presents in a dehydrated state due to pernicious vomiting urgently needs thiamine, as well as intravenous fluids.

Vascular disorders

Various vascular disorders occasionally cause psychosis, especially cerebral venous thrombosis. Puerperal women are liable to thrombosis, especially thrombophlebitis of the leg and pelvic veins; aseptic thrombi can also form in the dural venous sinuses and the cerebral veins draining into them. Most patients present with headache, vomiting, seizures and focal signs such as hemiplegia or dysphasia, but a minority of cases have a psychiatric presentation. The incidence is about 1 in 1,000 births in Europe and North America, but much higher in India, where large series have been collected. Psychosis is occasionally associated with other arterial or venous lesions: epidural anaesthesia can, if the dura is punctured, lead to leakage of cerebrospinal fluid and subdural haematoma. Arterial occlusion may be due to thrombi, amniotic fragments or air embolism. Postpartum cerebral angiopathy is a transitory arterial spasm of medium caliber cerebral arteries; it was first described in cocaine and amphetamine addicts, but can also complicate ergot and bromocriptine prescribed to inhibit lactation. Subarachnoid haemorrhage can occur after miscarriage or childbirth. All these usually present with neurological symptoms, and occasionally with delirium.

Epilepsy

Women with a lifelong epileptic history are liable to psychoses during pregnancy, labour and the puerperium. Women occasionally develop epilepsy for the first time in relation to their first pregnancy, and psychotic episodes have been described. There are over 30 cases in the literature.

Hypopituitarism

Pituitary necrosis following postpartum haemorrhage (Sheehan's syndrome) leads to failure and atrophy of the gonads, adrenal and thyroid. Chronic psychoses can supervene many years later, based on myxoedema, hypoglycaemia or Addisonian crisis. But these patients can also develop acute and recurrent psychoses, even as early as the puerperium.

Water intoxication

Hyponatraemia (which leads to delirium) can complicate oxytocin treatment, usually when given to induce an abortion. By 1975, 29 cases had been reported, of which three were severe or fatal.

Urea cycle disorders

Inborn errors of the Krebs-Henseleit urea cycle lead to hyperammonaemia. In carriers and heterozygotes, encephalopathy can develop in pregnancy or the puerperium. Cases have been described in carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1, argino-succinate synthetase and ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency.

Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis

The most recent form of organic childbearing psychosis to be described is encephalitis associated with antibodies to the NMDA receptor; these women often have ovarian teratomas. A Japanese review found ten reported during pregnancy and five after delivery.

Other organic psychoses with a specific link to childbearing

Sydenham's chorea, of which chorea gravidarum is a severe variant, has a number of psychiatric complications, which include psychosis. This usually develops during pregnancy, and occasionally after the birth or abortion. Its symptoms include severe hypnagogic hallucinations (hypnagogia), possibly the result of the extreme sleep disorder. This form of chorea was caused by streptococcal infections, which at present respond to antibiotics; it still occurs as a result of systemic lupus or anti-phospholipid syndromes. Only about 50 chorea psychoses have been reported, and only one this century; but it could return if the streptococcus escapes control. Alcohol withdrawal states (delirium tremens) occur in addicts whose intake has been interrupted by trauma or surgery; this can happen after childbirth. Postpartum confusional states have also been reported during withdrawal from opium and barbiturates.

One would expect acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) encephalitis to present in pregnancy or the puerperium, because it is a venereal disease that can progress rapidly; one case of AIDS encephalitis, presenting in the 28th week of gestation, has been reported from Haiti, and there may be others in countries where AIDS is rife. Anaemia is common in pregnancy and the puerperium, and folate deficiency has been linked to psychosis.

Incidental organic psychoses

The psychoses, mentioned above, all had a recognized connection with childbearing. But medical disorders with no specific link have presented with psychotic symptoms in the puerperium; in them the association seems to be fortuitous. They include neurosyphilis, encephalitis including von Economo's, meningitis, cerebral tumours, thyroid disease and ischaemic heart disease.

Society and culture

Support

In the UK, a series of workshops called "Unravelling Eve" were held in 2011, where women who had experienced postpartum depression shared their stories.

Notable cases in history and fiction

Harriet Sarah, Lady Mordaunt (1848–1906), formerly Harriet Moncreiffe, was the Scottish wife of an English baronet and Member of Parliament, Sir Charles Mordaunt. She was the defendant in a sensational divorce case in which the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) was embroiled; after a controversial trial lasting seven days, the jury determined that Lady Mordaunt was suffering from “puerperal mania” and her husband's petition for divorce was dismissed, while Lady Mordaunt was committed to an asylum.

Andrea Yates suffered from depression and, four months after the birth of her 5th child, relapsed, with psychotic features. Several weeks later she drowned all five children. Under the law in Texas, she was sentenced to life imprisonment, but, after a retrial, was committed to a mental hospital.

Guy de Maupassant, in his novel Mont-Oriol (1887) described a brief postpartum psychotic episode.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in her short story The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) described severe depression with psychotic features starting after childbirth, perhaps similar to that experienced by the author herself.

Stacey Slater, a fictional character in the long-running BBC soap-opera EastEnders suffered from postpartum psychosis in 2016, and was one of the show's biggest storylines that year.

Legal status

Postpartum psychosis, especially when there is a marked component of depression, has a small risk of filicide. In acute manic or cycloid cases, this risk is about 1%. Most of these incidents have occurred before the mother came under treatment, and some have been accidental. Several nations including Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and Italy recognize postpartum mental illness as a mitigating factor in cases where mothers kill their children. In the United States, such a legal distinction was not made as of 2009, and an insanity defense is not available in all states.

Britain has had the Infanticide Act since 1922.