From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Deinstitutionalisation (or deinstitutionalization) is the process of replacing long-stay psychiatric hospitals with less isolated community mental health services for those diagnosed with a mental disorder or developmental disability.

In the late 20th century, it led to the closure of many psychiatric

hospitals, as patients were increasingly cared for at home, in halfway houses and clinics, in regular hospitals, or not at all.

Deinstitutionalisation works in two ways. The first focuses on

reducing the population size of mental institutions by releasing

patients, shortening stays, and reducing both admissions and readmission

rates. The second focuses on reforming psychiatric care to reduce (or

avoid encouraging) feelings of dependency, hopelessness and other

behaviors that make it hard for patients to adjust to a life outside of

care.

The modern deinstitutionalisation movement was made possible by the discovery of psychiatric drugs in the mid-20th century, which could manage psychotic

episodes and reduced the need for patients to be confined and

restrained. Another major impetus was a series of socio-political

movements that campaigned for patient freedom. Lastly, there were

financial imperatives, with many governments also viewing it as a way to

save costs.

The movement to reduce institutionalisation was met with wide

acceptance in Western countries, though its effects have been the

subject of many debates. Critics of the policy include defenders of the

previous policies as well as those who believe the reforms did not go

far enough to provide freedom to patients.

History

19th century

Vienna's

Narrenturm—

German for "fools' tower"—was one of the earliest buildings specifically designed for mentally ill people. It was built in 1784.

The 19th century saw a large expansion in the number and size of asylums in Western industrialised

countries. In contrast to the prison-like asylums of old, these were

designed to be comfortable places where patients could live and be

treated, in keeping with the movement towards "moral treatment". In spite of these ideals, they became overstretched, non-therapeutic, isolated in location, and neglectful of patients.

20th century

By

the beginning of the 20th century, increasing admissions had resulted

in serious overcrowding, causing many problems for psychiatric

institutions. Funding was often cut, especially during periods of

economic decline and wartime. Asylums became notorious for poor living

conditions, lack of hygiene, overcrowding, ill-treatment, and abuse of patients; many patients starved to death.

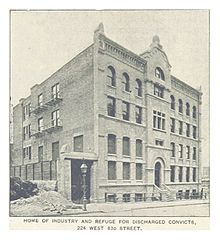

The first community-based alternatives were suggested and tentatively

implemented in the 1920s and 1930s, although asylum numbers continued to

increase up to the 1950s.

Origins of the modern movement

The advent of chlorpromazine

and other antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s and 1960s played an

important role in permitting deinstitutionalisation, but it was not

until social movements campaigned for reform in the 1960s that the

movement gained momentum.

A key text in the development of deinstitutionalisation was Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, a 1961 book by sociologist Erving Goffman. The book is one of the first sociological examinations of the social situation of mental patients, the hospital. Based on his participant observation field work, the book details Goffman's theory of the "total institution"

(principally in the example he gives, as the title of the book

indicates, mental institutions) and the process by which it takes

efforts to maintain predictable and regular behavior on the part of both

"guard" and "captor," suggesting that many of the features of such

institutions serve the ritual function of ensuring that both classes of

people know their function and social role, in other words of "institutionalizing" them.

Franco Basaglia, a leading Italian psychiatrist who inspired and was the architect of the psychiatric reform in Italy, also defined mental hospital as an oppressive, locked and total institution

in which prison-like, punitive rules are applied, in order to gradually

eliminate its own contents, and patients, doctors and nurses are all

subjected (at different levels) to the same process of institutionalism. Other critics went further and campaigned against all involuntary psychiatric treatment. In 1970, Goffman worked with Thomas Szasz and George Alexander to found the American Association for the Abolition of Involuntary Mental Hospitalisation (AAAIMH), who proposed abolishing all involuntary psychiatric intervention, particularly involuntary commitment, against individuals. The association provided legal help to psychiatric patients and published a journal, The Abolitionist, until it was dissolved in 1980.

Reform

The prevailing public arguments, time of onset, and pace of reforms varied by country. Leon Eisenberg lists three key factors that led to deinstitutionalisation gaining support.

The first factor was a series of socio-political campaigns for the

better treatment of patients. Some of these were spurred on by institutional abuse scandals in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Willowbrook State School in the United States and Ely Hospital

in the United Kingdom. The second factor was new psychiatric

medications made it more feasible to release people into the community

and the third factor was financial imperatives. There was an argument

that community services would be cheaper.

Mental health professionals, public officials, families, advocacy

groups, public citizens, and unions held differing views on

deinstitutionalisation.

However, the 20th Century marked the development of the first

community services designed specifically to divert

deinstitutionalization and to develop the first conversions from

institutional, governmental systems to community majority systems

(governmental-NGO-For Profit).

These services are so common throughout the world (e.g., individual and

family support services, groups homes, community and supportive living,

foster care and personal care homes, community residences, community

mental health offices, supported housing) that they are often "delinked"

from the term deinstitutionalization. Common historical figures in

deinstitutionalization in the US include Geraldo Rivera, Robert

Williams, Burton Blatt, Gunnar Dybwad, Michael Kennedy, Frank Laski, Steven J. Taylor, Douglas P. Biklen, David Braddock, Robert Bogdan and K. C. Lakin. in the fields of "intellectual disabilities" (e.g., amicus curae, Arc-US to the US Supreme Court; US state consent decrees).

Community organizing and development regarding the fields of

mental health, traumatic brain injury, aging (nursing facilities) and

children's institutions/private residential schools represent other

forms of diversion and "community re-entry". Paul Carling's book, Return

to the Community: Building Support Systems for People with Psychiatric

Disabilities describes mental health planning and services in that

regard, including for addressing the health and personal effects of

"long term institutionalization".

and the psychiatric field continued to research whether "hospitals"

(e.g., forced involuntary care in a state institution; voluntary,

private admissions) or community living was better.

US states have made substantial investments in the community, and

similar to Canada, shifted some but not all institutional funds to the

community sectors as deinstitutionalization. For example, NYS Education,

Health and Social Services Laws identify mental health personnel in the

state of New York, and the two term Obama Presidency in the US created a

high-level Office of Social and Behavioral Services.

The 20th Century marked the growth in a class of

deinstitutionalization and community researchers in the US and world,

including a class of university women.

These women follow university education on social control and the myths

of deinstitutionalization, including common forms of

transinstitutionalization such as transfers to prison systems in the

21st Century, "budget realignments", and the new subterfuge of community

data reporting.

Consequences

Community services that developed include supportive housing with full or partial supervision and specialised teams (such as assertive community treatment and early intervention teams).

Costs have been reported as generally equivalent to inpatient

hospitalisation, even lower in some cases (depending on how well or

poorly funded the community alternatives are). Although deinstitutionalisation has been positive for the majority of patients, it also has shortcomings.

Criticism of deinstitutionalisation takes two forms. Some, like E. Fuller Torrey, defend the use of psychiatric institutions and conclude that deinstitutionalisation was a move in the wrong direction.

Others, such as Walid Fakhoury and Stefan Priebe, argue that it was an

unsuccessful move in the right direction, suggesting that modern day

society faces the problem of "reinstitutionalisation". While coming from opposite viewpoints, both sets of critics argue that the policy left many patients homeless or in prison. Leon Eisenberg

has argued that deinstitutionalisation was generally positive for

patients, while noting that some were left homeless or without care.

Misconceptions

There

is a common perception by the public and media that people with mental

disorders are more likely to be dangerous and violent if released into

the community. However, a large 1998 study in Archives of General Psychiatry

suggested that discharged psychiatric patients without substance abuse

symptoms are no more likely to commit violence than others without

substance abuse symptoms in their neighborhoods, which were usually

economically deprived and high in substance abuse and crime. The study

also reported that a higher proportion of the patients than of the

others in the neighborhoods reported symptoms of substance abuse.

Findings on violence committed by those with mental disorders in

the community have been inconsistent and related to numerous factors; a

higher rate of more serious offences such as homicide have sometimes

been found but, despite high-profile homicide cases, the evidence

suggests this has not been increased by deinstitutionalisation.

The aggression and violence that does occur, in either direction, is

usually within family settings rather than between strangers.

Adequacy of treatment and support

Common

criticisms of the new community services are that they have been

uncoordinated, underfunded and unable to meet complex needs.

Problems with coordination arose because care was being provided by

multiple for-profit businesses, non-profit organizations and multiple

levels of government.

Torrey has opposed deinstitutionalisation in principle, arguing

that people with mental illness will be resistant to medical help due to

the nature of their conditions. These views have made him a

controversial figure in psychiatry. He believes that reducing psychiatrists' powers to use involuntary commitment led to many patients losing out on treatment, and that many who would have previously lived in institutions are now homeless or in prison.

Other critics argue that deinstitutionalisation had laudable

goals, but some patients lost out on care due to problems in the

execution stage. In a 1998 study of the effects of

deinstitutionalisation in the United Kingdom, Means and Smith argue that

the program had some successes, such as increasing the participation of

volunteers in mental healthcare, but that it was underfunded and let

down by a lack of coordination between the health service and social services.

Reinstitutionalisation

Some

mental health academics and campaigners have argued that

deinstitutionalisation was well-intentioned for trying to make patients

less dependent on psychiatric care, but in practice patients were still

left being dependent on the support of a mental healthcare system, a

phenomenon known as "reinstitutionalisation" or "transinstitutionalisation". The argument is that community services can leave the mentally

ill in a state of social isolation (even if it is not physical

isolation), frequently meeting other service users but having little

contact with the rest of the public community. Fakhoury and Priebe said

that instead of "community psychiatry", reforms established a "psychiatric community".

Julie Racino argues that having a closed social circle like this can

limit opportunities for mentally ill people to integrate with the wider

society, such as personal assistance services.

Thomas Szasz,

a longtime opponent of involuntary psychiatric treatment, argued that

the reforms never addressed the aspects of psychiatry that he objected

to, particularly his belief that mental illnesses are not true illnesses

but medicalized social and personal problems.

Medication

There was an increase in prescriptions of psychiatric medication in the years following deinstitutionalization.

Although most of these drugs had been discovered in the years before,

deinstitutionalisation made it far cheaper to care for a mental health

patient and increased the profitability of the drugs. Some researchers

argue that this created economic incentives to increase the frequency of

psychiatric diagnosis (and related diagnoses, such as ADHD in children) that did not happen in the era of costly hospitalized psychiatry.

In most countries (except some countries that are either in

extreme poverty or are hindered from importing psychiatric drugs by

their customs regulations), more than 10% of the population are now on some form of psychiatric medicine. This increases to more than 15% in some countries such as the United Kingdom. A 2012 study by Kales, Pierce and Greenblatt argued that these medicines were being overprescribed.

Victimisation

Moves

to community living and services have led to various concerns and

fears, from both the individuals themselves and other members of the

community. Over a quarter of individuals accessing community mental

health services in a US inner-city area are victims of at least one

violent crime per year, a proportion eleven times higher than the

inner-city average. The elevated victim rate holds for every category of

crime, including rape/sexual assault, other violent assaults, and

personal and property theft. Victimisation rates are similar to those with developmental disabilities.

Worldwide

Asia

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, a number of residential care services such as halfway houses, long-stay care homes, supported hostels

are provided for the discharged patients. In addition, community

support services such as rehabilitation day services and mental health

care have been launched to facilitate the patients' re-integration into

the community.

Japan

Unlike most developed countries, Japan has not followed a program of deinstitutionalisation. The number of hospital beds has risen steadily over the last few decades. Physical restraints

are used far more often. In 2014, more than 10,000 people were

restrained–the highest ever recorded, and more than double the number a

decade earlier.

In 2018, the Japanese Ministry of Health introduced revised guidelines

that placed more restrictions against the use of restraints.

Africa

Uganda has one psychiatric hospital.

There are only 40 psychiatrists in Uganda. The World Health

Organisation estimates that 90% of mentally ill people here never get

treatment.

Australia and Oceania

New Zealand

New Zealand established a reconciliation initiative in 2005 to address the ongoing compensation

payouts to ex-patients of state-run mental institutions in the 1970s to

1990s. A number of grievances were heard, including: poor reasons for

admissions; unsanitary and overcrowded conditions; lack of communication

to patients and family members; physical violence and sexual misconduct

and abuse; inadequate mechanisms for dealing with complaints; pressures

and difficulties for staff, within an authoritarian hierarchy based on containment; fear and humiliation in the misuse of seclusion; over-use and abuse of ECT, psychiatric medications, and other treatments as punishments, including group therapy, with continued adverse effects;

lack of support on discharge; interrupted lives and lost potential; and

continued stigma, prejudice, and emotional distress and trauma.

There were some references to instances of helpful aspects or

kindnesses despite the system. Participants were offered counselling to

help them deal with their experiences, along with advice on their

rights, including access to records and legal redress.

Europe

Republic of Ireland

The Republic of Ireland formerly had the highest psychiatric hospitalisation rate of any Western country.

The Lunatic (Asylums) Act, 1875, the Criminal Lunatics Act, 1838 and

the Private Lunatic Asylums Act of 1842 created a network of large

"district asylums." The Mental Treatment Act, 1945 caused some

modernisation but by 1958 the Republic of Ireland still had the highest

psychiatric hospitalisation rate in the world. In the 1950s and '60s

there was a transition to outpatient facilities and care homes.

The 1963 Irish Psychiatric Hosptial Census noted the extremely

high hospitalisation rate of unmarried people; six times the equivalent

in England and Wales. In all, about 1% of the population was living in a psychiatric hospital. In 1963–1978, Irish psychiatric hospitalisation rates were 2 1⁄2 times that of England.

Health Boards were set up in 1970 and the Health (Mental Services) Act

1981 was passed in order to prevent the wrongful hospitalisation of

individuals. In the 1990s, there was still about 25,000 patients in the

asylums.

In 2009, the government committed to closing two psychiatric

hospitals every year; in 2008, there were still 1,485 patients housed in

"inappropriate conditions." Today, Ireland's hospitalisation rate to a

position of equality with other comparable countries. In the public

sector virtually no patients remain in 19th-century mental hospitals;

acute care is provided in general hospital units. Acute private care is

still delivered in stand-alone psychiatric hospitals. The Central Mental Hospital in Dublin is used as a secure psychiatric hospital for criminal offenders, with room for 84 patients.

Italy

Italy was the first country to begin the deinstitutionalisation of

mental health care and to develop a community-based psychiatric system. The Italian system served as a model of effective service and paved the way for deinstitutionalisation of mental patients. Since the late 1960s, the Italian physician Giorgio Antonucci questioned the basis itself of psychiatry. After working with Edelweiss Cotti in 1968 at the Centro di Relazioni Umane in Cividale del Friuli

– an open ward created as an alternative to the psychiatric hospital –

from 1973 to 1996 Antonucci worked on the dismantling of the psychiatric

hospitals Osservanza and Luigi Lolli of Imola and the liberation – and restitution to life – of the people there secluded. In 1978, the Basaglia Law had started Italian psychiatric reform that resulted in the end of the Italian state mental hospital system in 1998.

The reform was focused on the gradual dismantlement of

psychiatric hospitals, which required an effective community mental

health service.

The object of community care was to reverse the long-accepted practice

of isolating the mentally ill in large institutions and to promote their

integration in a socially stimulating environment, while avoiding

subjecting them to excessive social pressures.

The work of Giorgio Antonucci,

instead of changing the form of commitment from the mental hospital to

other forms of coercion, questions the basis of psychiatry, affirming

that mental hospitals are the essence of psychiatry and rejecting any

possible reform of psychiatry, that must be completely eliminated.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the trend towards deinstitutionalisation began

in the 1950s. At the time, 0.4% of the population of England were

housed in asylums. The government of Harold Macmillan sponsored the Mental Health Act 1959, which removed the distinction between psychiatric hospitals and other types of hospitals. Enoch Powell,

the Minister of Health in the early 1960s, criticized psychiatric

institutions in his 1961 "Water Tower" speech and called for most of the

care to be transferred to general hospitals and the community. The campaigns of Barbara Robb and several scandals involving mistreatment at asylums (notably Ely Hospital) furthered the campaign. The Ely Hospital scandal led to an inquiry led by Brian Abel-Smith and a 1971 white paper that recommended further reform.

The policy of deinstitutionalisation came to be known as Care in the Community at the time it was taken up by the government of Margaret Thatcher. Large-scale closures of the old asylums began in the 1980s. By 2015, none remained.

North America

United States

The United States has experienced two main waves of

deinstitutionalisation. The first wave began in the 1950s and targeted

people with mental illness. The second wave began roughly 15 years later and focused on individuals who had been diagnosed with a developmental disability. Loren Mosher argues that deinstitutionalisation fully began in the 1970s and was due to financial incentives like SSI and Social Security Disability, rather than after the earlier introduction of psychiatric drugs.

The most important factors that led to deinstitutionalisation

were changing public attitudes to mental health and mental hospitals,

the introduction of psychiatric drugs and individual states' desires to reduce costs from mental hospitals. The federal government offered financial incentives to the states to achieve this goal. Stroman pinpoints World War II as the point when attitudes began to change. In 1946, Life magazine published one of the first exposés of the shortcomings of mental illness treatment. Also in 1946, Congress passed the National Mental Health Act of 1946, which created the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). NIMH was pivotal in funding research for the developing mental health field.

President John F. Kennedy had a special interest in the issue of mental health because his sister, Rosemary, had incurred brain damage after being lobotomised at the age of 23. His administration sponsored the successful passage of the Community Mental Health Act, one of the most important laws that led to deinstitutionalization. The movement continued to gain momentum during the Civil Rights Movement.

The 1965 amendments to Social Security shifted about 50% of the mental

health care costs from states to the federal government,

motivating state governments to promote deinstitutionalization. The

1970s saw the founding of several advocacy groups, including Liberation

of Mental Patients, Project Release, Insane Liberation Front, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

The lawsuits these activist groups filed led to some key court

rulings in the 1970s that increased the rights of patients. In 1973, a

federal district court ruled in Souder v. Brennan that whenever

patients in mental health institutions performed activity that conferred

an economic benefit to an institution, they had to be considered

employees and paid the minimum wage required by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. Following this ruling, institutional peonage was outlawed. In the 1975 ruling O'Connor v. Donaldson, the U.S. Supreme Court restricted the rights of states to incarcerate someone who was not violent. This was followed up with the 1978 ruling Addington v. Texas, further restricting states from confining anyone involuntarily for mental illness. In 1975, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ruled in favour of the Mental Patient's Liberation Front in Rogers v. Okin, establishing the right of a patient to refuse treatment. Later reforms included the Mental Health Parity Act, which required health insurers to give mental health patients equal coverage.

Other factors included scandals. A 1972 television broadcast exposed the abuse and neglect of 5,000 patients at the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island, New York. The Rosenhan's experiment

in 1973 caused several psychiatric hospitals to fail to notice fake

patients who showed no symptoms once they were institutionalized. The pitfalls of institutionalization were dramatized in an award-winning 1975 film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

In 1955, for every 100,000 US citizens there were 340 psychiatric

hospital beds. In 2005 that number had diminished to 17 per 100,000.

South America

In several South American countries,

such as in Argentina, the total number of beds in asylum-type

institutions has decreased, replaced by psychiatric inpatient units in

general hospitals and other local settings.

In Brazil, there are 6003 psychiatrists, 18,763 psychologists,

1985 social workers, 3119 nurses and 3589 occupational therapists

working for the Unified Health System (SUS). At primary care level,

there are 104,789 doctors, 184,437 nurses and nurse technicians and

210,887 health agents. The number of psychiatrists is roughly 5 per

100,000 inhabitants in the Southeast region, and the Northeast region

has less than 1 psychiatrist per 100,000 inhabitants. The number of

psychiatric nurses is insufficient in all geographical areas, and

psychologists outnumber other mental health professionals in all regions

of the country. The rate of beds in psychiatric hospitals in the

country is 27.17 beds per 100,000 inhabitants. The rate of patients in

psychiatric hospitals is 119 per 100,000 inhabitants. The average length

of stay in mental hospitals is 65.29 days.