Natural science is a branch of science concerned with the description, prediction, and understanding of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatability of findings are used to try to ensure the validity of scientific advances.

Natural science can be divided into two main branches: life science and physical science. Life science is alternatively known as biology, and physical science is subdivided into branches: physics, chemistry, Earth science, and astronomy. These branches of natural science may be further divided into more specialized branches (also known as fields). As empirical sciences, natural sciences use tools from the formal sciences, such as mathematics and logic, converting information about nature into measurements which can be explained as clear statements of the "laws of nature".

Modern natural science succeeded more classical approaches to natural philosophy, usually traced to Taoists traditions in Asia and in the Occident to ancient Greece. Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, and Newton debated the benefits of using approaches which were more mathematical and more experimental in a methodical way. Still, philosophical perspectives, conjectures, and presuppositions, often overlooked, remain necessary in natural science. Systematic data collection, including discovery science, succeeded natural history, which emerged in the 16th century by describing and classifying plants, animals, minerals, and so on. Today, "natural history" suggests observational descriptions aimed at popular audiences.

Criteria

Philosophers of science have suggested a number of criteria, including Karl Popper's controversial falsifiability criterion, to help them differentiate scientific endeavors from non-scientific ones. Validity, accuracy, and quality control, such as peer review and repeatability of findings, are amongst the most respected criteria in today's global scientific community.

Branches of natural science

Biology

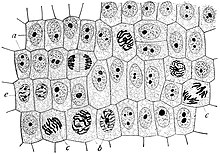

This field encompasses a diverse set of disciplines that examines phenomena related to living organisms. The scale of study can range from sub-component biophysics up to complex ecologies. Biology is concerned with the characteristics, classification and behaviors of organisms, as well as how species were formed and their interactions with each other and the environment.

The biological fields of botany, zoology, and medicine date back to early periods of civilization, while microbiology was introduced in the 17th century with the invention of the microscope. However, it was not until the 19th century that biology became a unified science. Once scientists discovered commonalities between all living things, it was decided they were best studied as a whole.

Some key developments in biology were the discovery of genetics; evolution through natural selection; the germ theory of disease and the application of the techniques of chemistry and physics at the level of the cell or organic molecule.

Modern biology is divided into subdisciplines by the type of organism and by the scale being studied. Molecular biology is the study of the fundamental chemistry of life, while cellular biology is the examination of the cell; the basic building block of all life. At a higher level, anatomy and physiology look at the internal structures, and their functions, of an organism, while ecology looks at how various organisms interrelate.

Earth science

Earth science (also known as geoscience), is an all-embracing term for the sciences related to the planet Earth, including geology, geography, geophysics, geochemistry, climatology, glaciology, hydrology, meteorology, and oceanography.

Although mining and precious stones have been human interests throughout the history of civilization, the development of the related sciences of economic geology and mineralogy did not occur until the 18th century. The study of the earth, particularly palaeontology, blossomed in the 19th century. The growth of other disciplines, such as geophysics, in the 20th century, led to the development of the theory of plate tectonics in the 1960s, which has had a similar effect on the Earth sciences as the theory of evolution had on biology. Earth sciences today are closely linked to petroleum and mineral resources, climate research and to environmental assessment and remediation.

Atmospheric sciences

Although sometimes considered in conjunction with the earth sciences, due to the independent development of its concepts, techniques and practices and also the fact of it having a wide range of sub-disciplines under its wing, atmospheric science is also considered a separate branch of natural science. This field studies the characteristics of different layers of the atmosphere from ground level to the edge of the space. The timescale of the study also varies from days to centuries. Sometimes the field also includes the study of climatic patterns on planets other than earth.

Oceanography

The serious study of oceans began in the early to mid-20th century. As a field of natural science, it is relatively young but stand-alone programs offer specializations in the subject. Though some controversies remain as to the categorization of the field under earth sciences, interdisciplinary sciences or as a separate field in its own right, most modern workers in the field agree that it has matured to a state that it has its own paradigms and practices. As such a big family of related studies spanning every aspect of the oceans is now classified under this field.

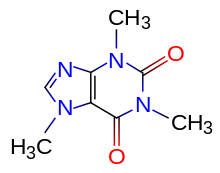

Chemistry

Constituting the scientific study of matter at the atomic and molecular scale, chemistry deals primarily with collections of atoms, such as gases, molecules, crystals, and metals. The composition, statistical properties, transformations and reactions of these materials are studied. Chemistry also involves understanding the properties and interactions of individual atoms and molecules for use in larger-scale applications.

Most chemical processes can be studied directly in a laboratory, using a series of (often well-tested) techniques for manipulating materials, as well as an understanding of the underlying processes. Chemistry is often called "the central science" because of its role in connecting the other natural sciences.

Early experiments in chemistry had their roots in the system of Alchemy, a set of beliefs combining mysticism with physical experiments. The science of chemistry began to develop with the work of Robert Boyle, the discoverer of gas, and Antoine Lavoisier, who developed the theory of the Conservation of mass.

The discovery of the chemical elements and atomic theory began to systematize this science, and researchers developed a fundamental understanding of states of matter, ions, chemical bonds and chemical reactions. The success of this science led to a complementary chemical industry that now plays a significant role in the world economy.

Physics

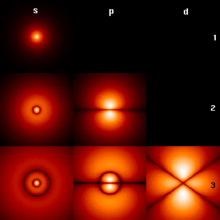

Physics embodies the study of the fundamental constituents of the universe, the forces and interactions they exert on one another, and the results produced by these interactions. In general, physics is regarded as the fundamental science, because all other natural sciences use and obey the principles and laws set down by the field. Physics relies heavily on mathematics as the logical framework for formulation and quantification of principles.

The study of the principles of the universe has a long history and largely derives from direct observation and experimentation. The formulation of theories about the governing laws of the universe has been central to the study of physics from very early on, with philosophy gradually yielding to systematic, quantitative experimental testing and observation as the source of verification. Key historical developments in physics include Isaac Newton's theory of universal gravitation and classical mechanics, an understanding of electricity and its relation to magnetism, Einstein's theories of special and general relativity, the development of thermodynamics, and the quantum mechanical model of atomic and subatomic physics.

The field of physics is extremely broad, and can include such diverse studies as quantum mechanics and theoretical physics, applied physics and optics. Modern physics is becoming increasingly specialized, where researchers tend to focus on a particular area rather than being "universalists" like Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Lev Landau, who worked in multiple areas.

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxies and comets. Astronomy is the study of everything in the universe beyond Earth's atmosphere. That includes objects we can see with our naked eyes. Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences.

Astronomers of early civilizations performed methodical observations of the night sky, and astronomical artifacts have been found from much earlier periods. There are two types of astronomy, observational astronomy and theoretical astronomy. Observational astronomy is focused on acquiring and analyzing data, mainly using basic principles of physics while Theoretical astronomy is oriented towards the development of computer or analytical models to describe astronomical objects and phenomena.

This discipline is the science of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the Earth's atmosphere. It is concerned with the evolution, physics, chemistry, meteorology, and motion of celestial objects, as well as the formation and development of the universe.

Astronomy includes the examination, study and modeling of stars, planets, comets. Most of the information used by astronomers is gathered by remote observation, although some laboratory reproduction of celestial phenomena has been performed (such as the molecular chemistry of the interstellar medium).

While the origins of the study of celestial features and phenomena can be traced back to antiquity, the scientific methodology of this field began to develop in the middle of the 17th century. A key factor was Galileo's introduction of the telescope to examine the night sky in more detail.

The mathematical treatment of astronomy began with Newton's development of celestial mechanics and the laws of gravitation, although it was triggered by earlier work of astronomers such as Kepler. By the 19th century, astronomy had developed into a formal science, with the introduction of instruments such as the spectroscope and photography, along with much-improved telescopes and the creation of professional observatories.

Interdisciplinary studies

The distinctions between the natural science disciplines are not always sharp, and they share a number of cross-discipline fields. Physics plays a significant role in the other natural sciences, as represented by astrophysics, geophysics, chemical physics and biophysics. Likewise chemistry is represented by such fields as biochemistry, chemical biology, geochemistry and astrochemistry.

A particular example of a scientific discipline that draws upon multiple natural sciences is environmental science. This field studies the interactions of physical, chemical, geological, and biological components of the environment, with particular regard to the effect of human activities and the impact on biodiversity and sustainability. This science also draws upon expertise from other fields such as economics, law, and social sciences.

A comparable discipline is oceanography, as it draws upon a similar breadth of scientific disciplines. Oceanography is sub-categorized into more specialized cross-disciplines, such as physical oceanography and marine biology. As the marine ecosystem is very large and diverse, marine biology is further divided into many subfields, including specializations in particular species.

There is also a subset of cross-disciplinary fields which, by the nature of the problems that they address, have strong currents that run counter to specialization. Put another way: In some fields of integrative application, specialists in more than one field are a key part of the most dialog. Such integrative fields, for example, include nanoscience, astrobiology, and complex system informatics.

Materials science

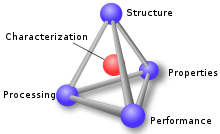

Materials science is a relatively new, interdisciplinary field which deals with the study of matter and its properties; as well as the discovery and design of new materials. Originally developed through the field of metallurgy, the study of the properties of materials and solids has now expanded into all materials. The field covers the chemistry, physics and engineering applications of materials including metals, ceramics, artificial polymers, and many others. The core of the field deals with relating structure of material with it properties.

It is at the forefront of research in science and engineering. It is an important part of forensic engineering (the investigation of materials, products, structures or components that fail or do not operate or function as intended, causing personal injury or damage to property) and failure analysis, the latter being the key to understanding, for example, the cause of various aviation accidents. Many of the most pressing scientific problems that are faced today are due to the limitations of the materials that are available and, as a result, breakthroughs in this field are likely to have a significant impact on the future of technology.

The basis of materials science involves studying the structure of materials, and relating them to their properties. Once a materials scientist knows about this structure-property correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a material in a certain application. The major determinants of the structure of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical elements and the way in which it has been processed into its final form. These characteristics, taken together and related through the laws of thermodynamics and kinetics, govern a material's microstructure, and thus its properties.

History

Some scholars trace the origins of natural science as far back as pre-literate human societies, where understanding the natural world was necessary for survival. People observed and built up knowledge about the behavior of animals and the usefulness of plants as food and medicine, which was passed down from generation to generation. These primitive understandings gave way to more formalized inquiry around 3500 to 3000 BC in the Mesopotamian and Ancient Egyptian cultures, which produced the first known written evidence of natural philosophy, the precursor of natural science. While the writings show an interest in astronomy, mathematics and other aspects of the physical world, the ultimate aim of inquiry about nature's workings was in all cases religious or mythological, not scientific.

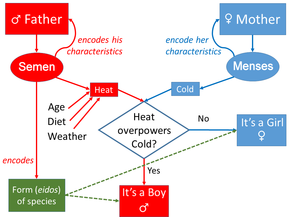

A tradition of scientific inquiry also emerged in Ancient China, where Taoist alchemists and philosophers experimented with elixirs to extend life and cure ailments. They focused on the yin and yang, or contrasting elements in nature; the yin was associated with femininity and coldness, while yang was associated with masculinity and warmth. The five phases – fire, earth, metal, wood and water – described a cycle of transformations in nature. Water turned into wood, which turned into fire when it burned. The ashes left by fire were earth. Using these principles, Chinese philosophers and doctors explored human anatomy, characterizing organs as predominantly yin or yang and understood the relationship between the pulse, the heart and the flow of blood in the body centuries before it became accepted in the West.

Little evidence survives of how Ancient Indian cultures around the Indus River understood nature, but some of their perspectives may be reflected in the Vedas, a set of sacred Hindu texts. They reveal a conception of the universe as ever-expanding and constantly being recycled and reformed. Surgeons in the Ayurvedic tradition saw health and illness as a combination of three humors: wind, bile and phlegm. A healthy life was the result of a balance among these humors. In Ayurvedic thought, the body consisted of five elements: earth, water, fire, wind and empty space. Ayurvedic surgeons performed complex surgeries and developed a detailed understanding of human anatomy.

Pre-Socratic philosophers in Ancient Greek culture brought natural philosophy a step closer to direct inquiry about cause and effect in nature between 600 and 400 BC, although an element of magic and mythology remained. Natural phenomena such as earthquakes and eclipses were explained increasingly in the context of nature itself instead of being attributed to angry gods. Thales of Miletus, an early philosopher who lived from 625 to 546 BC, explained earthquakes by theorizing that the world floated on water and that water was the fundamental element in nature. In the 5th century BC, Leucippus was an early exponent of atomism, the idea that the world is made up of fundamental indivisible particles. Pythagoras applied Greek innovations in mathematics to astronomy, and suggested that the earth was spherical.

Aristotelian natural philosophy (400 BC–1100 AD)

Later Socratic and Platonic thought focused on ethics, morals and art and did not attempt an investigation of the physical world; Plato criticized pre-Socratic thinkers as materialists and anti-religionists. Aristotle, however, a student of Plato who lived from 384 to 322 BC, paid closer attention to the natural world in his philosophy. In his History of Animals, he described the inner workings of 110 species, including the stingray, catfish and bee. He investigated chick embryos by breaking open eggs and observing them at various stages of development. Aristotle's works were influential through the 16th century, and he is considered to be the father of biology for his pioneering work in that science. He also presented philosophies about physics, nature, and astronomy using inductive reasoning in his works Physics and Meteorology.

While Aristotle considered natural philosophy more seriously than his predecessors, he approached it as a theoretical branch of science. Still, inspired by his work, Ancient Roman philosophers of the early 1st century AD, including Lucretius, Seneca and Pliny the Elder, wrote treatises that dealt with the rules of the natural world in varying degrees of depth. Many Ancient Roman Neoplatonists of the 3rd to the 6th centuries also adapted Aristotle's teachings on the physical world to a philosophy that emphasized spiritualism. Early medieval philosophers including Macrobius, Calcidius and Martianus Capella also examined the physical world, largely from a cosmological and cosmographical perspective, putting forth theories on the arrangement of celestial bodies and the heavens, which were posited as being composed of aether.

Aristotle's works on natural philosophy continued to be translated and studied amid the rise of the Byzantine Empire and Abbasid Caliphate.

In the Byzantine Empire John Philoponus, an Alexandrian Aristotelian commentator and Christian theologian, was the first who questioned Aristotle's teaching of physics. Unlike Aristotle who based his physics on verbal argument, Philoponus instead relied on observation, and argued for observation rather than resorting into verbal argument. He introduced the theory of impetus. John Philoponus' criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics served as inspiration for Galileo Galilei during the Scientific Revolution.

A revival in mathematics and science took place during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate from the 9th century onward, when Muslim scholars expanded upon Greek and Indian natural philosophy. The words alcohol, algebra and zenith all have Arabic roots.

Medieval natural philosophy (1100–1600)

Aristotle's works and other Greek natural philosophy did not reach the West until about the middle of the 12th century, when works were translated from Greek and Arabic into Latin. The development of European civilization later in the Middle Ages brought with it further advances in natural philosophy. European inventions such as the horseshoe, horse collar and crop rotation allowed for rapid population growth, eventually giving way to urbanization and the foundation of schools connected to monasteries and cathedrals in modern-day France and England. Aided by the schools, an approach to Christian theology developed that sought to answer questions about nature and other subjects using logic. This approach, however, was seen by some detractors as heresy. By the 12th century, Western European scholars and philosophers came into contact with a body of knowledge of which they had previously been ignorant: a large corpus of works in Greek and Arabic that were preserved by Islamic scholars. Through translation into Latin, Western Europe was introduced to Aristotle and his natural philosophy. These works were taught at new universities in Paris and Oxford by the early 13th century, although the practice was frowned upon by the Catholic church. A 1210 decree from the Synod of Paris ordered that "no lectures are to be held in Paris either publicly or privately using Aristotle's books on natural philosophy or the commentaries, and we forbid all this under pain of excommunication."

In the late Middle Ages, Spanish philosopher Dominicus Gundissalinus translated a treatise by the earlier Persian scholar Al-Farabi called On the Sciences into Latin, calling the study of the mechanics of nature scientia naturalis, or natural science. Gundissalinus also proposed his own classification of the natural sciences in his 1150 work On the Division of Philosophy. This was the first detailed classification of the sciences based on Greek and Arab philosophy to reach Western Europe. Gundissalinus defined natural science as "the science considering only things unabstracted and with motion," as opposed to mathematics and sciences that rely on mathematics. Following Al-Farabi, he then separated the sciences into eight parts, including physics, cosmology, meteorology, minerals science and plant and animal science.

Later philosophers made their own classifications of the natural sciences. Robert Kilwardby wrote On the Order of the Sciences in the 13th century that classed medicine as a mechanical science, along with agriculture, hunting and theater while defining natural science as the science that deals with bodies in motion. Roger Bacon, an English friar and philosopher, wrote that natural science dealt with "a principle of motion and rest, as in the parts of the elements of fire, air, earth and water, and in all inanimate things made from them." These sciences also covered plants, animals and celestial bodies. Later in the 13th century, a Catholic priest and theologian Thomas Aquinas defined natural science as dealing with "mobile beings" and "things which depend on a matter not only for their existence but also for their definition." There was wide agreement among scholars in medieval times that natural science was about bodies in motion, although there was division about the inclusion of fields including medicine, music and perspective. Philosophers pondered questions including the existence of a vacuum, whether motion could produce heat, the colors of rainbows, the motion of the earth, whether elemental chemicals exist and where in the atmosphere rain is formed.

In the centuries up through the end of the Middle Ages, natural science was often mingled with philosophies about magic and the occult. Natural philosophy appeared in a wide range of forms, from treatises to encyclopedias to commentaries on Aristotle. The interaction between natural philosophy and Christianity was complex during this period; some early theologians, including Tatian and Eusebius, considered natural philosophy an outcropping of pagan Greek science and were suspicious of it. Although some later Christian philosophers, including Aquinas, came to see natural science as a means of interpreting scripture, this suspicion persisted until the 12th and 13th centuries. The Condemnation of 1277, which forbade setting philosophy on a level equal with theology and the debate of religious constructs in a scientific context, showed the persistence with which Catholic leaders resisted the development of natural philosophy even from a theological perspective. Aquinas and Albertus Magnus, another Catholic theologian of the era, sought to distance theology from science in their works. "I don't see what one's interpretation of Aristotle has to do with the teaching of the faith," he wrote in 1271.

Newton and the scientific revolution (1600–1800)

By the 16th and 17th centuries, natural philosophy underwent an evolution beyond commentary on Aristotle as more early Greek philosophy was uncovered and translated. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century, the invention of the microscope and telescope, and the Protestant Reformation fundamentally altered the social context in which scientific inquiry evolved in the West. Christopher Columbus's discovery of a new world changed perceptions about the physical makeup of the world, while observations by Copernicus, Tyco Brahe and Galileo brought a more accurate picture of the solar system as heliocentric and proved many of Aristotle's theories about the heavenly bodies false. A number of 17th-century philosophers, including Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Francis Bacon made a break from the past by rejecting Aristotle and his medieval followers outright, calling their approach to natural philosophy as superficial.

The titles of Galileo's work Two New Sciences and Johannes Kepler's New Astronomy underscored the atmosphere of change that took hold in the 17th century as Aristotle was dismissed in favor of novel methods of inquiry into the natural world. Bacon was instrumental in popularizing this change; he argued that people should use the arts and sciences to gain dominion over nature. To achieve this, he wrote that "human life [must] be endowed with new discoveries and powers." He defined natural philosophy as "the knowledge of Causes and secret motions of things; and enlarging the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible." Bacon proposed that scientific inquiry be supported by the state and fed by the collaborative research of scientists, a vision that was unprecedented in its scope, ambition and form at the time. Natural philosophers came to view nature increasingly as a mechanism that could be taken apart and understood, much like a complex clock. Natural philosophers including Isaac Newton, Evangelista Torricelli and Francesco Redi conducted experiments focusing on the flow of water, measuring atmospheric pressure using a barometer and disproving spontaneous generation. Scientific societies and scientific journals emerged and were spread widely through the printing press, touching off the scientific revolution. Newton in 1687 published his The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, or Principia Mathematica, which set the groundwork for physical laws that remained current until the 19th century.

Some modern scholars, including Andrew Cunningham, Perry Williams and Floris Cohen, argue that natural philosophy is not properly called a science, and that genuine scientific inquiry began only with the scientific revolution. According to Cohen, "the emancipation of science from an overarching entity called 'natural philosophy' is one defining characteristic of the Scientific Revolution." Other historians of science, including Edward Grant, contend that the scientific revolution that blossomed in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries occurred when principles learned in the exact sciences of optics, mechanics and astronomy began to be applied to questions raised by natural philosophy. Grant argues that Newton attempted to expose the mathematical basis of nature – the immutable rules it obeyed – and in doing so joined natural philosophy and mathematics for the first time, producing an early work of modern physics.

The scientific revolution, which began to take hold in the 17th century, represented a sharp break from Aristotelian modes of inquiry. One of its principal advances was the use of the scientific method to investigate nature. Data was collected and repeatable measurements made in experiments. Scientists then formed hypotheses to explain the results of these experiments. The hypothesis was then tested using the principle of falsifiability to prove or disprove its accuracy. The natural sciences continued to be called natural philosophy, but the adoption of the scientific method took science beyond the realm of philosophical conjecture and introduced a more structured way of examining nature.

Newton, an English mathematician, and physicist, was the seminal figure in the scientific revolution. Drawing on advances made in astronomy by Copernicus, Brahe, and Kepler, Newton derived the universal law of gravitation and laws of motion. These laws applied both on earth and in outer space, uniting two spheres of the physical world previously thought to function independently of each other, according to separate physical rules. Newton, for example, showed that the tides were caused by the gravitational pull of the moon. Another of Newton's advances was to make mathematics a powerful explanatory tool for natural phenomena. While natural philosophers had long used mathematics as a means of measurement and analysis, its principles were not used as a means of understanding cause and effect in nature until Newton.

In the 18th century and 19th century, scientists including Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, Alessandro Volta, and Michael Faraday built upon Newtonian mechanics by exploring electromagnetism, or the interplay of forces with positive and negative charges on electrically charged particles. Faraday proposed that forces in nature operated in "fields" that filled space. The idea of fields contrasted with the Newtonian construct of gravitation as simply "action at a distance", or the attraction of objects with nothing in the space between them to intervene. James Clerk Maxwell in the 19th century unified these discoveries in a coherent theory of electrodynamics. Using mathematical equations and experimentation, Maxwell discovered that space was filled with charged particles that could act upon themselves and each other and that they were a medium for the transmission of charged waves.

Significant advances in chemistry also took place during the scientific revolution. Antoine Lavoisier, a French chemist, refuted the phlogiston theory, which posited that things burned by releasing "phlogiston" into the air. Joseph Priestley had discovered oxygen in the 18th century, but Lavoisier discovered that combustion was the result of oxidation. He also constructed a table of 33 elements and invented modern chemical nomenclature. Formal biological science remained in its infancy in the 18th century, when the focus lay upon the classification and categorization of natural life. This growth in natural history was led by Carl Linnaeus, whose 1735 taxonomy of the natural world is still in use. Linnaeus in the 1750s introduced scientific names for all his species.

19th-century developments (1800–1900)

By the 19th century, the study of science had come into the purview of professionals and institutions. In so doing, it gradually acquired the more modern name of natural science. The term scientist was coined by William Whewell in an 1834 review of Mary Somerville's On the Connexion of the Sciences. But the word did not enter general use until nearly the end of the same century.

Modern natural science (1900–present)

According to a famous 1923 textbook, Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances, by the American chemist Gilbert N. Lewis and the American physical chemist Merle Randall, the natural sciences contain three great branches:

Aside from the logical and mathematical sciences, there are three great branches of natural science which stand apart by reason of the variety of far reaching deductions drawn from a small number of primary postulates — they are mechanics, electrodynamics, and thermodynamics.

Today, natural sciences are more commonly divided into life sciences, such as botany and zoology; and physical sciences, which include physics, chemistry, astronomy, and Earth sciences.