| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luminal |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682007 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Low |

| Routes of administration | by mouth (PO), rectal (PR), parenteral (intramuscular and intravenous) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Protein binding | 20 to 45% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly CYP2C19) |

| Onset of action | within 5 min (IV) and 30 min (PO) |

| Elimination half-life | 53 to 118 hours |

| Duration of action | 4 hrs to 2 days |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.007 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

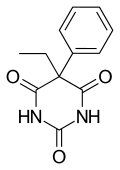

| Formula | C12H12N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 232.239 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, or by the trade name Luminal, is a medication of the barbiturate type. It is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of certain types of epilepsy in developing countries. In the developed world, it is commonly used to treat seizures in young children, while other medications are generally used in older children and adults. It may be used intravenously, injected into a muscle, or taken by mouth. The injectable form may be used to treat status epilepticus. Phenobarbital is occasionally used to treat trouble sleeping, anxiety, and drug withdrawal and to help with surgery. It usually begins working within five minutes when used intravenously and half an hour when administered by mouth. Its effects last for between four hours and two days.

Side effects include a decreased level of consciousness along with a decreased effort to breathe. There is concern about both abuse and withdrawal following long-term use. It may also increase the risk of suicide. It is pregnancy category B or D (depending on how it is taken) in the United States and category D in Australia, meaning that it may cause harm when taken by pregnant women. If used during breastfeeding it may result in drowsiness in the baby. A lower dose is recommended in those with poor liver or kidney function, as well as elderly people. Phenobarbital, like other barbiturates works by increasing the activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.

Phenobarbital was discovered in 1912 and is the oldest still commonly used anti-seizure medication. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. It is the least expensive anti-seizure medication at around US$5 a year in the developing world. Access, however, may be difficult as some countries label it as a controlled drug.

Medical uses

Phenobarbital is used in the treatment of all types of seizures, except absence seizures. It is no less effective at seizure control than phenytoin, however phenobarbital is not as well tolerated. Phenobarbital may provide a clinical advantage over carbamazepine for treating partial onset seizures. Carbamazepine may provide a clinical advantage over phenobarbital for generalized onset tonic-clonic seizures. Its very long active half-life (53–118 hours) means for some people doses do not have to be taken every day, particularly once the dose has been stabilized over a period of several weeks or months, and seizures are effectively controlled.

The first-line drugs for treatment of status epilepticus are benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam or diazepam. If these fail, then phenytoin may be used, with phenobarbital being an alternative in the US, but used only third-line in the UK. Failing that, the only treatment is anaesthesia in intensive care. The World Health Organization (WHO) gives phenobarbital a first-line recommendation in the developing world and it is commonly used there.

Phenobarbital is the first-line choice for the treatment of neonatal seizures. Concerns that neonatal seizures in themselves could be harmful make most physicians treat them aggressively. No reliable evidence, though, supports this approach.

Phenobarbital is sometimes used for alcohol detoxification and benzodiazepine detoxification for its sedative and anti-convulsant properties. The benzodiazepines chlordiazepoxide (Librium) and oxazepam (Serax) have largely replaced phenobarbital for detoxification.

Phenobarbital is useful for insomnia and anxiety.

Other uses

Phenobarbital properties can effectively reduce tremors and seizures associated with abrupt withdrawal from benzodiazepines.

Phenobarbital is a cytochrome P450 inducer, and is used to reduce the toxicity of some drugs.

Phenobarbital is occasionally prescribed in low doses to aid in the conjugation of bilirubin in people with Crigler–Najjar syndrome, type II, or in patients with Gilbert's syndrome.

Phenobarbital can also be used to relieve cyclic vomiting syndrome symptoms.

Phenobarbital is a commonly used agent in high purity and dosage for lethal injection of "death row" criminals.

In infants suspected of neonatal biliary atresia, phenobarbital is used in preparation for a 99mTc-IDA hepatobiliary (HIDA; hepatobiliary 99mTc-iminodiacetic acid) study that differentiates atresia from hepatitis or cholestasis.

Phenobarbital is used as a secondary agent to treat newborns with neonatal abstinence syndrome, a condition of withdrawal symptoms from exposure to opioid drugs in utero.

In massive doses, phenobarbital is prescribed to terminally ill patients to allow them to end their life through physician-assisted suicide.

Like other barbiturates, phenobarbital can be used recreationally, but this is reported to be relatively infrequent.

Side effects

Sedation and hypnosis are the principal side effects (occasionally, they are also the intended effects) of phenobarbital. Central nervous system effects, such as dizziness, nystagmus and ataxia, are also common. In elderly patients, it may cause excitement and confusion, while in children, it may result in paradoxical hyperactivity.

Phenobarbital is a cytochrome P450 hepatic enzyme inducer. It binds transcription factor receptors that activate cytochrome P450 transcription, thereby increasing its amount and thus its activity. Due to this higher amount of CYP450, drugs that are metabolized by the CYP450 enzyme system will have decreased effectiveness. This is because the increased CYP450 activity increases the clearance of the drug, reducing the amount of time they have to work.

Caution is to be used with children. Among anti-convulsant drugs, behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.

Contraindications

Acute intermittent porphyria, hypersensitivity to any barbiturate, prior dependence on barbiturates, severe respiratory insufficiency (as with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), severe liver failure, pregnancy, and breastfeeding are contraindications for phenobarbital use.

Overdose

Phenobarbital causes a depression of the body's systems, mainly the central and peripheral nervous systems. Thus, the main characteristic of phenobarbital overdose is a "slowing" of bodily functions, including decreased consciousness (even coma), bradycardia, bradypnea, hypothermia, and hypotension (in massive overdoses). Overdose may also lead to pulmonary edema and acute renal failure as a result of shock, and can result in death.

The electroencephalogram (EEG) of a person with phenobarbital overdose may show a marked decrease in electrical activity, to the point of mimicking brain death. This is due to profound depression of the central nervous system, and is usually reversible.

Treatment of phenobarbital overdose is supportive, and mainly consists of the maintenance of airway patency (through endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation), correction of bradycardia and hypotension (with intravenous fluids and vasopressors, if necessary), and removal of as much drug as possible from the body. In very large overdoses, multi-dose activated charcoal is a mainstay of treatment as the drug undergoes enterohepatic recirculation. Urine alkalization (achieved with sodium bicarbonate) enhances renal excretion. Hemodialysis is effective in removing phenobarbital from the body, and may reduce its half-life by up to 90%. No specific antidote for barbiturate poisoning is available.

Mechanism of action

Phenobarbitol is as an allosteric modulator which extends the amount of time the chloride ion channel is open by interacting with GABAA receptor subunits. Through this action, phenobarbital increases the flow of chloride ions into the neuron which decreases the excitability of the post-synaptic neuron. Hyperpolarizing this post-synaptic membrane leads to a decrease in the general excitatory aspects of the post-synaptic neuron. By making it harder to depolarize the neuron, the threshold for the action potential of the post-synaptic neuron will be increased. Phenobarbital stimulates GABA to accomplish this hyperpolarization. Direct blockade of excitatory glutamate signaling is also believed to contribute to the hypnotic/anticonvulsant effect that is observed with the barbiturates.

Pharmacokinetics

Phenobarbital has an oral bioavailability of about 90%. Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached eight to 12 hours after oral administration. It is one of the longest-acting barbiturates available – it remains in the body for a very long time (half-life of two to seven days) and has very low protein binding (20 to 45%). Phenobarbital is metabolized by the liver, mainly through hydroxylation and glucuronidation, and induces many isozymes of the cytochrome P450 system. Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is specifically induced by phenobarbital via the CAR/RXR nuclear receptor heterodimer. It is excreted primarily by the kidneys.

Veterinary uses

Phenobarbital is one of the initial drugs of choice to treat epilepsy in dogs, and is the initial drug of choice to treat epilepsy in cats.

It is also used to treat feline hyperesthesia syndrome in cats when anti-obsessional therapies prove ineffective.

It may also be used to treat seizures in horses when benzodiazepine treatment has failed or is contraindicated.

History

The first barbiturate drug, barbital, was synthesized in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering and was first marketed as Veronal by Friedr. Bayer et comp. By 1904, several related drugs, including phenobarbital, had been synthesized by Fischer. Phenobarbital was brought to market in 1912 by the drug company Bayer as the brand Luminal. It remained a commonly prescribed sedative and hypnotic until the introduction of benzodiazepines in the 1960s.

Phenobarbital's soporific, sedative and hypnotic properties were well known in 1912, but it was not yet known to be an effective anti-convulsant. The young doctor Alfred Hauptmann gave it to his epilepsy patients as a tranquilizer and discovered their seizures were susceptible to the drug. Hauptmann performed a careful study of his patients over an extended period. Most of these patients were using the only effective drug then available, bromide, which had terrible side effects and limited efficacy. On phenobarbital, their epilepsy was much improved: The worst patients suffered fewer and lighter seizures and some patients became seizure-free. In addition, they improved physically and mentally as bromides were removed from their regimen. Patients who had been institutionalised due to the severity of their epilepsy were able to leave and, in some cases, resume employment. Hauptmann dismissed concerns that its effectiveness in stalling seizures could lead to patients suffering a build-up that needed to be "discharged". As he expected, withdrawal of the drug led to an increase in seizure frequency – it was not a cure. The drug was quickly adopted as the first widely effective anti-convulsant, though World War I delayed its introduction in the U.S.

In 1939, a German family asked Adolf Hitler to have their disabled son killed; the five-month-old boy was given a lethal dose of Luminal after Hitler sent his own doctor to examine him. A few days later 15 psychiatrists were summoned to Hitler's Chancellery and directed to commence a clandestine euthanasia program.

In 1940, at a clinic in Ansbach, Germany, around 50 intellectually disabled children were injected with Luminal and killed that way. A plaque was erected in their memory in 1988 in the local hospital at Feuchtwanger Strasse 38, although a newer plaque does not mention that patients were killed using barbiturates on site. Luminal was used in the Nazi children's euthanasia program until at least 1943.

Phenobarbital was used to treat neonatal jaundice by increasing liver metabolism and thus lowering bilirubin levels. In the 1950s, phototherapy was discovered, and became the standard treatment.

Phenobarbital was used for over 25 years as prophylaxis in the treatment of febrile seizures. Although an effective treatment in preventing recurrent febrile seizures, it had no positive effect on patient outcome or risk of developing epilepsy. The treatment of simple febrile seizures with anticonvulsant prophylaxis is no longer recommended.

Society and culture

Names

Phenobarbital is the INN and phenobarbitone is the BAN.

Synthesis

Barbiturate drugs are obtained via condensation reactions between a derivative of diethyl malonate and urea in the presence of a strong base. The synthesis of phenobarbital uses this common approach as well but differs in the way in which this malonate derivative is obtained. The reason for this difference is due to the fact that aryl halides do not typically undergo nucleophilic substitution in Malonic ester synthesis in the same way as aliphatic organosulfates or halocarbons do. To overcome this lack of chemical reactivity two dominant synthetic approaches using benzyl cyanide as a starting material have been developed:

The first of these methods consists of a Pinner reaction of benzyl cyanide, giving phenylacetic acid ethyl ester. Subsequently, this ester undergoes cross Claisen condensation using diethyl oxalate, giving diethyl ester of phenyloxobutandioic acid. Upon heating this intermediate easily loses carbon monoxide, yielding diethyl phenylmalonate. Malonic ester synthesis using ethyl bromide leads to the formation of α-phenyl-α-ethylmalonic ester. Finally a condensation reaction with urea gives phenobarbital.

The second approach utilizes diethyl carbonate in the presence of a strong base to give α-phenylcyanoacetic ester. Alkylation of this ester using ethyl bromide proceeds via a nitrile anion intermediate to give the α-phenyl-α-ethylcyanoacetic ester. This product is then further converted into the 4-iminoderivative upon condensation with urea. Finally acidic hydrolysis of the resulting product gives phenobarbital.

Regulation

The level of regulation includes Schedule IV non-narcotic (depressant) (ACSCN 2285) in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act 1970—but along with a few other barbiturates and at least one benzodiazepine, and codeine, dionine, or dihydrocodeine at low concentrations, it also has exempt prescription and had at least one exempt OTC combination drug now more tightly regulated for its ephedrine content. The phenobarbitone/phenobarbital exists in subtherapeutic doses which add up to an effective dose to counter the overstimulation and possible seizures from a deliberate overdose in ephedrine tablets for asthma, which are now regulated at the federal and state level as: a restricted OTC medicine and/or watched precursor, uncontrolled but watched/restricted prescription drug & watched precursor, a Schedule II, III, IV, or V prescription-only controlled substance & watched precursor, or a Schedule V (which also has possible regulations at the county/parish, town, city, or district as well aside from the fact that the pharmacist can also choose not to sell it, and photo ID and signing a register is required) exempt Non-Narcotic restricted/watched OTC medicine.

Selected overdoses

The Japanese officers aboard the German submarine U-234 killed themselves with phenobarbital while the German crew members were on their way to the US to surrender (but before Japan had surrendered).

A mysterious woman, known as the Isdal Woman, was found dead in Bergen, Norway, on 29 November 1970. Her death was caused by some combination of burns, phenobarbital, and carbon monoxide poisoning; many theories about her death have been posited, and it is believed that she may have been a spy.

British veterinarian Donald Sinclair, better known as the character Siegfried Farnon in the "All Creatures Great and Small" book series by James Herriot, committed suicide at the age of 84 by injecting himself with an overdose of phenobarbital. Activist Abbie Hoffman also committed suicide by consuming phenobarbital, combined with alcohol, on April 12, 1989; the residue of around 150 pills was found in his body at autopsy. Also dying from an overdose was British actress Phyllis Barry in 1954 and actress/model Margaux Hemingway in 1996.

Thirty-nine members of the Heaven's Gate UFO religious group committed mass suicide in March 1997 by drinking a lethal dose of phenobarbital and vodka "and then lay down to die" hoping to enter an alien spacecraft.