From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dementia

| Dementia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Senility, senile dementia |

| |

| Image of a man diagnosed with dementia in the 1800s | |

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Decreased ability to think and remember, emotional problems, problems with language, decreased motivation |

| Usual onset | Gradual |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Alzheimer's disease, vascular disease, Lewy body disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. |

| Diagnostic method | Cognitive testing (Mini-Mental State Examination) |

| Differential diagnosis | Delirium Hypothyroidism |

| Prevention | Early education, prevent high blood pressure, prevent obesity, no smoking, social engagement |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

| Medication | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (small benefit) |

| Frequency | 50 million (2020) |

| Deaths | 2.4 million (2016) |

Dementia occurs as a set of related symptoms when the brain is damaged by injury or disease. The symptoms involve progressive impairments to memory, thinking, and behavior, that affect the ability to look after oneself as a measure of carrying out everyday activities. Other common symptoms include emotional problems, difficulties with language, and decreased motivation. The symptoms may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages. Dementia is not a disorder of consciousness, and consciousness is not usually affected. A diagnosis of dementia requires a change from a person's usual mental functioning, and a greater cognitive decline than that due to normal aging. Several diseases, and injuries to the brain such as a stroke, can give rise to dementia. However, the most common cause is Alzheimer's disease a neurodegenerative disorder. Dementia has a significant effect on the individual, relationships and caregivers. In DSM-5, dementia has been reclassified as a major neurocognitive disorder, with varying degrees of severity, and many causative subtypes.

Causative subtypes of dementia may be based on a known potential cause such as Parkinson's disease, for Parkinson's disease dementia; Huntington's disease for Huntingtons disease dementia; vascular disease for vascular dementia; brain injury including stroke often results in vascular dementia; or many other medical conditions including HIV infection for HIV dementia; and prion diseases. Subtypes may be based on various symptoms as may be due to a neurodegenerative disorder such as Alzheimer's disease; frontotemporal lobar degeneration for frontotemporal dementia; or Lewy body disease for dementia with Lewy bodies. More than one type of dementia, known as mixed dementia, may exist together. Diagnosis is usually based on history of the illness and cognitive testing with imaging. Blood tests may be taken to rule out other possible causes that may be reversible such as an underactive thyroid, and to determine the subtype. The Mini-Mental State Examination is one commonly used cognitive test. The greatest risk factor for developing dementia is aging, however dementia is not a normal part of aging. Several risk factors for dementia are described with some such as smoking, and obesity being preventable by lifestyle changes. Screening the general population for the disorder is not recommended.

There is no known cure for dementia. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil are often used and may be beneficial in mild to moderate disorder. The overall benefit, however, may be minor. There are many measures that can improve the quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers. Cognitive and behavioral interventions may be appropriate. Educating and providing emotional support to the caregiver is important. Exercise programs may be beneficial with respect to activities of daily living and may potentially improve outcomes. Treatment of behavioral problems with antipsychotics is common but not usually recommended, due to the limited benefit and the side effects, including an increased risk of death.

It was estimated in 2020 that dementia affected about 50 million people worldwide. This is an increase on the 2016 estimate of 43.8 million, and more than double the estimated 20.2 million in 1990. The number of cases is increasing by around 10 million every year. About 10% of people develop the disorder at some point in their lives, commonly as a result of aging. About 3% of people between the ages of 65–74 have dementia, 19% between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age. In 2016 dementia resulted in about 2.4 million deaths, up from 0.8 million in 1990. In 2020 it was reported that dementia was listed as one of the top ten causes of death worldwide. Another report stated that in 2016 it was the fifth leading cause of death. As more people are living longer, dementia is becoming more common. For people of a specific age, however, it may be becoming less frequent in the developed world, due to a decrease in modifiable risk factors made possible by greater financial and educational resources. It is one of the most common causes of disability among the old. Worldwide the cost of dementia in 2015 was put at US$818 billion. People with dementia are often physically or chemically restrained to a greater degree than necessary, raising issues of human rights. Social stigma against those affected is common.

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of dementia, are termed as the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, also known as the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Behavioral symptoms can include agitation, restlessness, inappropriate behavior, sexual disinhibition, and aggression which can be verbal or physical. These symptoms may result from impairments in cognitive inhibition. Psychological symptoms can include depression, psychotic hallucinations and delusions, apathy, and anxiety. The most commonly affected areas include memory, visuospatial function affecting perception and orientation, language, attention and problem solving. The rate of symptoms progression may be described as occurring in a continuum over several stages, and varies across the dementia subtypes. Most types of dementia are slowly progressive with some deterioration of the brain well established before signs of the disorder become apparent. Often there are other conditions present such as high blood pressure, or diabetes, and there can sometimes be as many as four of these comorbidities.

Stages

The course of dementia is often described in four stages that show a pattern of progressive cognitive and functional impairment. However, the use of numeric scales allow for more detailed descriptions. These scales include: the Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia (GDS or Reisberg Scale), the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST), and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Using the GDS which more accurately identifies each stage of the disease progression, a more detailed course is described in seven stages – two of which are broken down further into five and six degrees. Stage 7(f) is the final stage.

Pre-dementia states

Pre-dementia states include pre-clinical and prodromal stages.

Pre-clinical

Sensory dysfunction is claimed for this stage which may precede the first clinical signs of dementia by up to ten years. Most notably the sense of smell is lost. The loss of the sense of smell is associated with depression and loss of appetite leading to poor nutrition. It is suggested that this dysfunction may come about because the olfactory epithelium is exposed to the environment. The lack of blood-brain-barrier protection here means that toxic elements can enter and cause damage to the chemosensory networks.

Prodromal

Pre-dementia states considered as prodromal are mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and mild behavioral impairment (MBI).

Kynurenine is a metabolite of tryptophan that regulates microbiome signalling, immune cell response, and neuronal excitation. A disruption in the kynurenine pathway may be associated with the neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive prognosis in mild dementia.

In this stage signs and symptoms may be subtle. Often, the early signs become apparent when looking back. 70% of those diagnosed with MCI later progress to dementia. In MCI, changes in the person's brain have been happening for a long time, but symptoms are just beginning to appear. These problems, however, are not severe enough to affect daily function. If and when they do, the diagnosis becomes dementia. They may have some memory trouble and trouble finding words, but they solve everyday problems and competently handle their life affairs.

Mild cognitive impairment has been relisted in both DSM-5, and ICD-11, as mild neurocognitive disorders, – milder forms of the major neurocognitive disorder (dementia) subtypes.

Early stages

In the early stage of dementia, symptoms become noticeable to other people. In addition, the symptoms begin to interfere with daily activities, and will register a score on a Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE). MMSE scores are set at 24 to 30 for a normal coginitive rating and lower scores reflect severity of symptoms. The symptoms are dependent on the type of dementia. More complicated chores and tasks around the house or at work become more difficult. The person can usually still take care of themselves but may forget things like taking pills or doing laundry and may need prompting or reminders.

The symptoms of early dementia usually include memory difficulty, but can also include some word-finding problems, and problems with executive functions of planning and organization. Managing finances may prove difficult. Other signs might be getting lost in new places, repeating things, and personality changes.

In some types of dementia, such as dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia, personality changes and difficulty with organization and planning may be the first signs.

Middle stages

As dementia progresses, initial symptoms generally worsen. The rate of decline is different for each person. MMSE scores between 6–17 signal moderate dementia. For example, people with moderate Alzheimer's dementia lose almost all new information. People with dementia may be severely impaired in solving problems, and their social judgment is usually also impaired. They cannot usually function outside their own home, and generally should not be left alone. They may be able to do simple chores around the house but not much else, and begin to require assistance for personal care and hygiene beyond simple reminders. A lack of insight into having the condition will become evident.

Late stages

People with late-stage dementia typically turn increasingly inward and need assistance with most or all of their personal care. Persons with dementia in the late stages usually need 24-hour supervision to ensure their personal safety, and meeting of basic needs. If left unsupervised, they may wander or fall; may not recognize common dangers such as a hot stove; or may not realize that they need to use the bathroom and become incontinent. They may not want to get out of bed, or may need assistance doing so. Commonly, the person no longer recognizes familiar faces. They may have significant changes in sleeping habits or have trouble sleeping at all.

Changes in eating frequently occur. Cognitive awareness is needed for eating and swallowing and progressive cognitive decline results in eating and swallowing difficulties. This can cause food to be refused, or choked on, and help with feeding will often be required. For ease of feeding, food may be liquidized into a thick purée.

Subtypes

Many of the subtypes of dementia are neurodegenerative, and protein toxicity is a cardinal feature of these.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60–70% of cases of dementia worldwide. The most common symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are short-term memory loss and word-finding difficulties. Trouble with visuospatial functioning (getting lost often), reasoning, judgment and insight fail. Insight refers to whether or not the person realizes they have memory problems.

Common early symptoms of Alzheimer's include repetition, getting lost, difficulties tracking bills, problems with cooking especially new or complicated meals, forgetting to take medication and word-finding problems.

The part of the brain most affected by Alzheimer's is the hippocampus. Other parts that show atrophy (shrinking) include the temporal and parietal lobes. Although this pattern of brain shrinkage suggests Alzheimer's, it is variable and a brain scan is insufficient for a diagnosis. The relationship between anesthesia and AD is unclear.

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia accounts for at least 20% of dementia cases, making it the second most common type. It is caused by disease or injury affecting the blood supply to the brain, typically involving a series of mini-strokes. The symptoms of this dementia depend on where in the brain the strokes occurred and whether the blood vessels affected were large or small. Multiple injuries can cause progressive dementia over time, while a single injury located in an area critical for cognition such as the hippocampus, or thalamus, can lead to sudden cognitive decline. Elements of vascular dementia may be present in all other forms of dementia.

Brain scans may show evidence of multiple strokes of different sizes in various locations. People with vascular dementia tend to have risk factors for disease of the blood vessels, such as tobacco use, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol, diabetes, or other signs of vascular disease such as a previous heart attack or angina.

Lewy body dementias

Lewy body dementias are dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD). They are classified in DSM5 as mild or major neurocognitive disorders due to Lewy bodies.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

The prodromal symptoms of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) include mild cognitive impairment, and delirium onset. The symptoms of DLB are more frequent, more severe, and earlier presenting than in the other dementia subtypes. Dementia with Lewy bodies has the primary symptoms of fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention; REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD); one or more of the main features of parkinsonism, not due to medication or stroke; and repeated visual hallucinations. The visual hallucinations in DLB are generally vivid hallucinations of people or animals and they often occur when someone is about to fall asleep or wake up. Other prominent symptoms include problems with planning (executive function) and difficulty with visual-spatial function, and disruption in autonomic bodily functions. Abnormal sleep behaviors may begin before cognitive decline is observed and are a core feature of DLB. RBD is diagnosed either by sleep study recording or, when sleep studies cannot be performed, by medical history and validated questionnaires.

Parkinson's disease dementia

Parkinson's disease is a Lewy body disease that often progresses to Parkinson's disease dementia following a period of dementia-free Parkinson's disease.

Frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementias (FTDs) are characterized by drastic personality changes and language difficulties. In all FTDs, the person has a relatively early social withdrawal and early lack of insight. Memory problems are not a main feature. There are six main types of FTD. The first has major symptoms in personality and behavior. This is called behavioral variant FTD (bv-FTD) and is the most common. The hallmark feature of bv-FTD is impulsive behaviour, and this can be detected in pre-dementia states. In bv-FTD, the person shows a change in personal hygiene, becomes rigid in their thinking, and rarely acknowledges problems; they are socially withdrawn, and often have a drastic increase in appetite. They may become socially inappropriate. For example, they may make inappropriate sexual comments, or may begin using pornography openly. One of the most common signs is apathy, or not caring about anything. Apathy, however, is a common symptom in many dementias.

Two types of FTD feature aphasia (language problems) as the main symptom. One type is called semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (SV-PPA). The main feature of this is the loss of the meaning of words. It may begin with difficulty naming things. The person eventually may lose the meaning of objects as well. For example, a drawing of a bird, dog, and an airplane in someone with FTD may all appear almost the same. In a classic test for this, a patient is shown a picture of a pyramid and below it a picture of both a palm tree and a pine tree. The person is asked to say which one goes best with the pyramid. In SV-PPA the person cannot answer that question. The other type is called non-fluent agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (NFA-PPA). This is mainly a problem with producing speech. They have trouble finding the right words, but mostly they have a difficulty coordinating the muscles they need to speak. Eventually, someone with NFA-PPA only uses one-syllable words or may become totally mute.

A frontotemporal dementia associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) known as (FTD-ALS) includes the symptoms of FTD (behavior, language and movement problems) co-occurring with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (loss of motor neurons). Two FTD-related disorders are progressive supranuclear palsy (also classed as a Parkinson-plus syndrome), and corticobasal degeneration. These disorders are tau-associated.

Huntington's disease dementia

Huntington's disease is a degenerative disease caused by mutations in a single gene. Symptoms include cognitive impairment and this usually declines further into dementia.

HIV-associated dementia

HIV-associated dementia results as a late stage from HIV infection, and mostly affects younger people. The essential features of HIV-associated dementia are disabling cognitive impairment accompanied by motor dysfunction, speech problems and behavioral change. Cognitive impairment is characterised by mental slowness, trouble with memory and poor concentration. Motor symptoms include a loss of fine motor control leading to clumsiness, poor balance and tremors. Behavioral changes may include apathy, lethargy and diminished emotional responses and spontaneity. Histopathologically, it is identified by the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into the central nervous system (CNS), gliosis, pallor of myelin sheaths, abnormalities of dendritic processes and neuronal loss.

Dementia due to prion disease

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is a rapidly progressive prion disease that typically causes dementia that worsens over weeks to months.

Alcohol-related dementia also called alcohol-related brain damage occurs as a result of excessive use of alcohol particularly as a substance abuse disorder. Different factors can be involved in this development including thiamine deficiency and age vulnerability. A degree of brain damage is seen in more than 70% of those with alcohol use disorder. Brain regions affected are similar to those that are affected by aging, and also by Alzheimer's disease. Regions showing loss of volume include the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, the cerebellum, thalamus, and hippocampus. This loss can be more notable, with greater cognitive impairments seen in those aged 65 years and older.

Mixed dementia

More than one type of dementia, known as mixed dementia, may exist together in about 10% of dementia cases. The most common type of mixed dementia is Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. This particular type of mixed dementia's main onsets are a mixture of old age, high blood pressure, and damage to blood vessels in the brain.

Diagnosis of mixed dementia can be difficult, as often only one type will predominate. This makes the treatment of people with mixed dementia uncommon, with many people missing out on potentially helpful treatments. Mixed dementia can mean that symptoms onset earlier, and worsen more quickly since more parts of the brain will be affected.

Other conditions

Chronic inflammatory conditions that may affect the brain and cognition include Behçet's disease, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, Sjögren's syndrome, lupus, celiac disease, and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. These types of dementias can rapidly progress, but usually have a good response to early treatment. This consists of immunomodulators or steroid administration, or in certain cases, the elimination of the causative agent. A 2019 review found no association between celiac disease and dementia overall but a potential association with vascular dementia. A 2018 review found a link between celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity and cognitive impairment and that celiac disease may be associated with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. A strict gluten-free diet started early may protect against dementia associated with gluten-related disorders.

Cases of easily reversible dementia include hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, Lyme disease, and neurosyphilis. For Lyme disease and neurosyphilis, testing should be done if risk factors are present. Because risk factors are often difficult to determine, testing for neurosyphilis and Lyme disease, as well as other mentioned factors, may be undertaken as a matter of course where dementia is suspected.

Many other medical and neurological conditions include dementia only late in the illness. For example, a proportion of patients with Parkinson's disease develop dementia, though widely varying figures are quoted for this proportion. When dementia occurs in Parkinson's disease, the underlying cause may be dementia with Lewy bodies or Alzheimer's disease, or both. Cognitive impairment also occurs in the Parkinson-plus syndromes of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration (and the same underlying pathology may cause the clinical syndromes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration). Although the acute porphyrias may cause episodes of confusion and psychiatric disturbance, dementia is a rare feature of these rare diseases. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) is a type of dementia that primarily affects people in their 80s or 90s and in which TDP-43 protein deposits in the limbic portion of the brain.

Hereditary disorders that can also cause dementia include: some metabolic disorders, lysosomal storage disorders, leukodystrophies, and spinocerebellar ataxias.

Diagnosis

Symptoms are similar across dementia types and it is difficult to diagnose by symptoms alone. Diagnosis may be aided by brain scanning techniques. In many cases, the diagnosis requires a brain biopsy to become final, but this is rarely recommended (though it can be performed at autopsy). In those who are getting older, general screening for cognitive impairment using cognitive testing or early diagnosis of dementia has not been shown to improve outcomes. However, screening exams are useful in 65+ persons with memory complaints.

Normally, symptoms must be present for at least six months to support a diagnosis. Cognitive dysfunction of shorter duration is called delirium. Delirium can be easily confused with dementia due to similar symptoms. Delirium is characterized by a sudden onset, fluctuating course, a short duration (often lasting from hours to weeks), and is primarily related to a somatic (or medical) disturbance. In comparison, dementia has typically a long, slow onset (except in the cases of a stroke or trauma), slow decline of mental functioning, as well as a longer trajectory (from months to years).

Some mental illnesses, including depression and psychosis, may produce symptoms that must be differentiated from both delirium and dementia. Therefore, any dementia evaluation should include a depression screening such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory or the Geriatric Depression Scale. Physicians used to think that people with memory complaints had depression and not dementia (because they thought that those with dementia are generally unaware of their memory problems). This is called pseudodementia. However, in recent years researchers have realized that many older people with memory complaints in fact have MCI, the earliest stage of dementia. Depression should always remain high on the list of possibilities, however, for an elderly person with memory trouble.

Changes in thinking, hearing and vision are associated with normal ageing and can cause problems when diagnosing dementia due to the similarities.

Cognitive testing

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|

| MMSE | 71%–92% | 56%–96% |

|

| 3MS | 83%–93.5% | 85%–90% |

|

| AMTS | 73%–100% | 71%–100% |

|

Various brief tests (5–15 minutes) have reasonable reliability to screen for dementia. While many tests have been studied,[88][89][90] presently the mini mental state examination (MMSE) is the best studied and most commonly used. The MMSE is a useful tool for helping to diagnose dementia if the results are interpreted along with an assessment of a person's personality, their ability to perform activities of daily living, and their behaviour. Other cognitive tests include the abbreviated mental test score (AMTS), the, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS), the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI), the Trail-making test, and the clock drawing test. The MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) is a reliable screening test and is available online for free in 35 different languages. The MoCA has also been shown somewhat better at detecting mild cognitive impairment than the MMSE. The AD-8 – a screening questionnaire used to assess changes in function related to cognitive decline – is potentially useful, but is not diagnostic, is variable, and has risk of bias. Brief cognitive tests may be affected by factors such as age, education and ethnicity.

Another approach to screening for dementia is to ask an informant (relative or other supporter) to fill out a questionnaire about the person's everyday cognitive functioning. Informant questionnaires provide complementary information to brief cognitive tests. Probably the best known questionnaire of this sort is the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE). Evidence is insufficient to determine how accurate the IQCODE is for diagnosing or predicting dementia. The Alzheimer's Disease Caregiver Questionnaire is another tool. It is about 90% accurate for Alzheimer's when by a caregiver. The General Practitioner Assessment Of Cognition combines both a patient assessment and an informant interview. It was specifically designed for use in the primary care setting.

Clinical neuropsychologists provide diagnostic consultation following administration of a full battery of cognitive testing, often lasting several hours, to determine functional patterns of decline associated with varying types of dementia. Tests of memory, executive function, processing speed, attention and language skills are relevant, as well as tests of emotional and psychological adjustment. These tests assist with ruling out other etiologies and determining relative cognitive decline over time or from estimates of prior cognitive abilities.

Laboratory tests

Routine blood tests are usually performed to rule out treatable causes. These include tests for vitamin B12, folic acid, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), C-reactive protein, full blood count, electrolytes, calcium, renal function, and liver enzymes. Abnormalities may suggest vitamin deficiency, infection, or other problems that commonly cause confusion or disorientation in the elderly.

Imaging

A CT scan or MRI scan is commonly performed, although these tests do not pick up diffuse metabolic changes associated with dementia in a person who shows no gross neurological problems (such as paralysis or weakness) on a neurological exam. CT or MRI may suggest normal pressure hydrocephalus, a potentially reversible cause of dementia, and can yield information relevant to other types of dementia, such as infarction (stroke) that would point at a vascular type of dementia.

The functional neuroimaging modalities of SPECT and PET are more useful in assessing long-standing cognitive dysfunction, since they have shown similar ability to diagnose dementia as a clinical exam and cognitive testing. The ability of SPECT to differentiate vascular dementia from Alzheimer's disease, appears superior to differentiation by clinical exam.

The value of PiB-PET imaging using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) as a radiotracer has been established in predictive diagnosis, particularly Alzheimer's disease.

Risk factors

The number of associated risk factors for dementia was increased from nine to twelve in 2020. The three added ones are over-indulgence in alcohol, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution. The other nine risk factors are: lower levels of education; high blood pressure; hearing loss; smoking; obesity; depression; inactivity; diabetes, and low social contact. Several of the group are known vascular risk factors that may be able to be reduced or eliminated. A reduction in a number of these risk factors can give a positive outcome. The decreased risk achieved by adopting a healthy lifestyle is seen even in those with a high genetic risk.

The two most modifiable risk factors for dementia are physical inactivity and lack of cognitive stimulation. Physical activity, in particular aerobic exercise is associated with a reduction in age-related brain tissue loss, and neurotoxic factors thereby preserving brain volume and neuronal integrity; cognitive activity strengthens neural plasticity and together they help to support cognitive reserve. The neglect of these risk factors diminishes this reserve.

Studies suggest that sensory impairments of vision and hearing are modifiable risk factors for dementia. These impairments may precede the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease for example, by many years. Hearing loss may lead to social isolation which negatively affects cognition. Social isolation is also identified as a modifiable risk factor. Age-related hearing loss in midlife is linked to cognitive impairment in late life, and is seen as a risk factor for the development of Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Such hearing loss may be caused by a central auditory processing disorder that makes the understanding of speech against background noise difficult. Age-related hearing loss is characterised by slowed central processing of auditory information. Worldwide, mid-life hearing loss may account for around 9% of dementia cases.

Evidence suggests that frailty may increase the risk of cognitive decline, and dementia, and that the inverse also holds of cognitive impairment increasing the risk of frailty. Prevention of frailty may help to prevent cognitive decline.

A 2018 review however concluded that no medications have good evidence of a preventive effect, including blood pressure medications. A 2020 review found a decrease in the risk of dementia or cognitive problems from 7.5% to 7.0% with blood pressure lowering medications.

Dental health

Limited evidence links poor oral health to cognitive decline. However, failure to perform tooth brushing and gingival inflammation can be used as dementia risk predictors.

Oral bacteria

The link between Alzheimer's and gum disease is oral bacteria. In the oral cavity, bacterial species include P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, P. intermedia, and T. forsythia. Six oral treponema spirochetes have been examined in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. Spirochetes are neurotropic in nature, meaning they act to destroy nerve tissue and create inflammation. Inflammatory pathogens are an indicator of Alzheimer's disease and bacteria related to gum disease have been found in the brains of Alzheimer's disease sufferers. The bacteria invade nerve tissue in the brain, increasing the permeability of the blood-brain barrier and promoting the onset of Alzheimer's. Individuals with a plethora of tooth plaque risk cognitive decline. Poor oral hygiene can have an adverse effect on speech and nutrition, causing general and cognitive health decline.

Oral viruses

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) has been found in more than 70% of those aged over 50. HSV persists in the peripheral nervous system and can be triggered by stress, illness or fatigue. High proportions of viral-associated proteins in amyloid plaques or neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) confirm the involvement of HSV-1 in Alzheimer's disease pathology. NFTs are known as the primary marker of Alzheimer's disease. HSV-1 produces the main components of NFTs.

Diet

Diet is seen to be a modifiable risk factor for the development of dementia. The Mediterranean diet, and the DASH diet are both associated with less cognitive decline. A different approach has been to incorporate elements of both of these diets into one known as the MIND diet.

These diets are generally low in saturated fats while providing a good source of carbohydrates, mainly those that help stabilize blood sugar and insulin levels. Raised blood sugar levels over a long time, can damage nerves and cause memory problems if they are not managed. Nutritional factors associated with the proposed diets for reducing dementia risk, include unsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants vitamin E vitamin C and flavonoids, vitamin B, and vitamin D.

The MIND diet may be more protective but further studies are needed. The Mediterranean diet seems to be more protective against Alzheimer's than DASH but there are no consistent findings against dementia in general. The role of olive oil needs further study as it may be one of the most important components in reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

In those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, a strict gluten-free diet may relieve the symptoms given a mild cognitive impairment. Once dementia is advanced no evidence suggests that a gluten free diet is useful.

Omega-3 fatty acid supplements do not appear to benefit or harm people with mild to moderate symptoms. However, there is good evidence that omega-3 incorporation into the diet is of benefit in treating depression, a common symptom, and potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia.

Other interventions

Among otherwise healthy older people, computerized cognitive training may, for a time, improve memory. However it is not known whether it prevents dementia. Exercise has poor evidence of preventing dementia. In those with normal mental function evidence for medications is poor. The same applies to supplements.

Management

Except for the reversible types, no cure has been developed. acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are often used early in the disorder course; however, benefit is generally small. Treatments other than medication appear to be better for agitation and aggression. Cognitive and behavioral interventions may be appropriate. Some evidence suggests that education and support for the person with dementia, as well as caregivers and family members, improves outcomes. Exercise programs are beneficial with respect to activities of daily living, and potentially improve dementia.

The effect of therapies can be evaluated for example by assessing agitation using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI); by assessing mood and engagement with the Menorah Park Engagement Scale (MPES); and the Observed Emotion Rating Scale (OERS) or by assessing indicators for depression using the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) or a simplified version thereof.

Psychological and psychosocial therapies

Psychological therapies for dementia include some limited evidence for reminiscence therapy (namely, some positive effects in the areas of quality of life, cognition, communication and mood – the first three particularly in care home settings), some benefit for cognitive reframing for caretakers, unclear evidence for validation therapy and tentative evidence for mental exercises, such as cognitive stimulation programs for people with mild to moderate dementia. A 2020 Cochrane review found that offering personally tailored activities could help reduce challenging behavior and may improve quality of life. The reviewed studies (5 RCTs with 262 participants) were unable to draw any conclusions about impact on individual affect or on improvements for the quality of life for the caregiver.

Adult daycare centers as well as special care units in nursing homes often provide specialized care for dementia patients. Daycare centers offer supervision, recreation, meals, and limited health care to participants, as well as providing respite for caregivers. In addition, home care can provide one-to-one support and care in the home allowing for more individualized attention that is needed as the disorder progresses. Psychiatric nurses can make a distinctive contribution to people's mental health.

Since dementia impairs normal communication due to changes in receptive and expressive language, as well as the ability to plan and problem solve, agitated behaviour is often a form of communication for the person with dementia. Actively searching for a potential cause, such as pain, physical illness, or overstimulation can be helpful in reducing agitation. Additionally, using an "ABC analysis of behaviour" can be a useful tool for understanding behavior in people with dementia. It involves looking at the antecedents (A), behavior (B), and consequences (C) associated with an event to help define the problem and prevent further incidents that may arise if the person's needs are misunderstood. The strongest evidence for non-pharmacological therapies for the management of changed behaviours in dementia is for using such approaches. Low quality evidence suggests that regular (at least five sessions of) music therapy may help institutionalized residents. It may reduce depressive symptoms and improve overall behaviour. It may also supply a beneficial effect on emotional well-being and quality of life, as well as reduce anxiety. In 2003, The Alzheimer’s Society established 'Singing for the Brain' (SftB) a project based on pilot studies which suggested that the activity encouraged participation and facilitated the learning of new songs. The sessions combine aspects of reminiscence therapy and music. Musical and interpersonal connectedness can underscore the value of the person and improve quality of life.

Some London hospitals found that using color, designs, pictures and lights helped people with dementia adjust to being at the hospital. These adjustments to the layout of the dementia wings at these hospitals helped patients by preventing confusion.

Life story work as part of reminiscence therapy, and video biographies have been found to address the needs of clients and their caregivers in various ways, offering the client the opportunity to leave a legacy and enhance their personhood and also benefitting youth who participate in such work. Such interventions be more beneficial when undertaken at a relatively early stage of dementia. They may also be problematic in those who have difficulties in processing past experiences

Animal-assisted therapy has been found to be helpful. Drawbacks may be that pets are not always welcomed in a communal space in the care setting. An animal may pose a risk to residents, or may be perceived to be dangerous. Certain animals may also be regarded as “unclean” or “dangerous” by some cultural groups.

Medications

No medications have been shown to prevent or cure dementia. Medications may be used to treat the behavioural and cognitive symptoms, but have no effect on the underlying disease process.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may be useful for Alzheimer 's disease, Parkinson's disease dementia, DLB, or vascular dementia. The quality of the evidence is poor and the benefit is small. No difference has been shown between the agents in this family. In a minority of people side effects include a slow heart rate and fainting. Rivastigmine is recommended for treating symptoms in Parkinson's disease dementia.

Before prescribing antipsychotic medication in the elderly, an assessment for an underlying cause of the behavior is needed. Severe and life-threatening reactions occur in almost half of people with DLB, and can be fatal after a single dose. People with Lewy body dementias who take neuroleptics are at risk for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a life-threatening illness. Extreme caution is required in the use of antipsychotic medication in people with DLB because of their sensitivity to these agents. Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat dementia only if non-drug therapies have not worked, and the person's actions threaten themselves or others. Aggressive behavior changes are sometimes the result of other solvable problems, that could make treatment with antipsychotics unnecessary. Because people with dementia can be aggressive, resistant to their treatment, and otherwise disruptive, sometimes antipsychotic drugs are considered as a therapy in response. These drugs have risky adverse effects, including increasing the person's chance of stroke and death. Given these adverse events and small benefit antipsychotics are avoided whenever possible. Generally, stopping antipsychotics for people with dementia does not cause problems, even in those who have been on them a long time.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockers such as memantine may be of benefit but the evidence is less conclusive than for AChEIs. Due to their differing mechanisms of action memantine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can be used in combination however the benefit is slight.

An extract of Ginkgo biloba known as EGb 761 has been widely used for treating mild to moderate dementia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Its use is approved throughout Europe. The World Federation of Biological Psychiatry guidelines lists EGb 761 with the same weight of evidence (level B) given to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and mementine. EGb 761 is the only one that showed improvement of symptoms in both AD and vascular dementia. EGb 761 is seen as being able to play an important role either on its own or as an add-on particularly when other therapies prove ineffective. EGb 761 is seen to be neuroprotective; it is a free radical scavenger, improves mitochondrial function, and modulates serotonin and dopamine levels. Many studies of its use in mild to moderate dementia have shown it to significantly improve cognitive function, activities of daily living, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and quality of life. However, its use has not been shown to prevent the progression of dementia.

While depression is frequently associated with dementia, the use of antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) do not appear to affect outcomes. However, the SSRIs sertraline and citalopram have been demonstrated to reduce symptoms of agitation, compared to placebo.

The use of medications to alleviate sleep disturbances that people with dementia often experience has not been well researched, even for medications that are commonly prescribed. In 2012 the American Geriatrics Society recommended that benzodiazepines such as diazepam, and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, be avoided for people with dementia due to the risks of increased cognitive impairment and falls. Benzodiazepines are also known to promote delirium. Additionally, little evidence supports the effectiveness of benzodiazepines in this population. No clear evidence shows that melatonin or ramelteon improves sleep for people with dementia due to Alzheimer's, but it is used to treat REM sleep behavior disorder in dementia with Lewy bodies. Limited evidence suggests that a low dose of trazodone may improve sleep, however more research is needed.

No solid evidence indicates that folate or vitamin B12 improves outcomes in those with cognitive problems. Statins have no benefit in dementia. Medications for other health conditions may need to be managed differently for a person who has a dementia diagnosis. It is unclear whether blood pressure medication and dementia are linked. People may experience an increase in cardiovascular-related events if these medications are withdrawn.

The Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health Conditions in Dementia (MATCH-D) criteria can help identify ways that a diagnosis of dementia changes medication management for other health conditions. These criteria were developed because people with dementia live with an average of five other chronic diseases, which are often managed with medications.

Pain

As people age, they experience more health problems, and most health problems associated with aging carry a substantial burden of pain; therefore, between 25% and 50% of older adults experience persistent pain. Seniors with dementia experience the same prevalence of conditions likely to cause pain as seniors without dementia. Pain is often overlooked in older adults and, when screened for, is often poorly assessed, especially among those with dementia, since they become incapable of informing others of their pain. Beyond the issue of humane care, unrelieved pain has functional implications. Persistent pain can lead to decreased ambulation, depressed mood, sleep disturbances, impaired appetite, and exacerbation of cognitive impairment and pain-related interference with activity is a factor contributing to falls in the elderly.

Although persistent pain in people with dementia is difficult to communicate, diagnose, and treat, failure to address persistent pain has profound functional, psychosocial and quality of life implications for this vulnerable population. Health professionals often lack the skills and usually lack the time needed to recognize, accurately assess and adequately monitor pain in people with dementia. Family members and friends can make a valuable contribution to the care of a person with dementia by learning to recognize and assess their pain. Educational resources and observational assessment tools are available. Eating difficulties

Persons with dementia may have difficulty eating. Whenever it is available as an option, the recommended response to eating problems is having a caretaker assist them. A secondary option for people who cannot swallow effectively is to consider gastrostomy feeding tube placement as a way to give nutrition. However, in bringing comfort and maintaining functional status while lowering risk of aspiration pneumonia and death, assistance with oral feeding is at least as good as tube feeding. Tube-feeding is associated with agitation, increased use of physical and chemical restraints and worsening pressure ulcers. Tube feedings may cause fluid overload, diarrhea, abdominal pain, local complications, less human interaction and may increase the risk of aspiration.

Benefits in those with advanced dementia has not been shown. The risks of using tube feeding include agitation, rejection by the person (pulling out the tube, or otherwise physical or chemical immobilization to prevent them from doing this), or developing pressure ulcers. The procedure is directly related to a 1% fatality rate with a 3% major complication rate. The percentage of people at end of life with dementia using feeding tubes in the US has dropped from 12% in 2000 to 6% as of 2014.

Exercise

Exercise programs may improve the ability of people with dementia to perform daily activities, but the best type of exercise is still unclear. Getting more exercise can slow the development of cognitive problems such as dementia, proving to reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease by about 50%. A balance of strength exercise to help muscles pump blood to the brain, and balance exercises are recommended for aging people, a suggested amount of about 2 and a half hours per week can reduce risks of cognitive decay as well as other health risks like falling.

Alternative medicine

Aromatherapy and massage have unclear evidence. Studies support the efficacy and safety of cannabinoids in relieving behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Palliative care

Given the progressive and terminal nature of dementia, palliative care can be helpful to patients and their caregivers by helping people with the disorder and their caregivers understand what to expect, deal with loss of physical and mental abilities, support the person's wishes and goals including surrogate decision making, and discuss wishes for or against CPR and life support. Because the decline can be rapid, and because most people prefer to allow the person with dementia to make their own decisions, palliative care involvement before the late stages of dementia is recommended. Further research is required to determine the appropriate palliative care interventions and how well they help people with advanced dementia.

Person-centered care helps maintain the dignity of people with dementia.

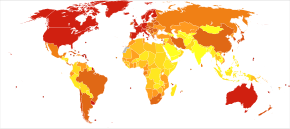

Epidemiology

<100 100–120 120–140 140–160 160–180 180–200 | 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 >300 |

The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer's disease. Other common types include vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia. Less common causes include normal pressure hydrocephalus, Parkinson's disease dementia, syphilis, HIV, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. The number of cases of dementia worldwide in 2016 was estimated at 43.8 million. with 58% living in low and middle income countries. The prevalence of dementia differs in different world regions, ranging from 4.7% in Central Europe to 8.7% in North Africa/Middle East; the prevalence in other regions is estimated to be between 5.6 and 7.6%. The number of people living with dementia is estimated to double every 20 years. In 2016 dementia resulted in about 2.4 million deaths, up from 0.8 million in 1990. Around two-thirds of individuals with dementia live in low- and middle-income countries, where the sharpest increases in numbers were predicted in a 2009 study.

The annual incidence of dementia diagnosis is over 9.9 million worldwide. Almost half of new dementia cases occur in Asia, followed by Europe (25%), the Americas (18%) and Africa (8%). The incidence of dementia increases exponentially with age, doubling with every 6.3 year increase in age. Dementia affects 5% of the population older than 65 and 20–40% of those older than 85. Rates are slightly higher in women than men at ages 65 and greater.

Dementia impacts not only individuals with dementia, but also their carers and the wider society. Among people aged 60 years and over, dementia is ranked the 9th most burdensome condition according to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates. The global costs of dementia was around US$818 billion in 2015, a 35.4% increase from US$604 billion in 2010.

History

Until the end of the 19th century, dementia was a much broader clinical concept. It included mental illness and any type of psychosocial incapacity, including reversible conditions. Dementia at this time simply referred to anyone who had lost the ability to reason, and was applied equally to psychosis, "organic" diseases like syphilis that destroy the brain, and to the dementia associated with old age, which was attributed to "hardening of the arteries".

Dementia has been referred to in medical texts since antiquity. One of the earliest known allusions to dementia is attributed to the 7th-century BC Greek philosopher Pythagoras, who divided the human lifespan into six distinct phases: 0–6 (infancy), 7–21 (adolescence), 22–49 (young adulthood), 50–62 (middle age), 63–79 (old age), and 80–death (advanced age). The last two he described as the "senium", a period of mental and physical decay, and that the final phase was when "the scene of mortal existence closes after a great length of time that very fortunately, few of the human species arrive at, where the mind is reduced to the imbecility of the first epoch of infancy". In 550 BC, the Athenian statesman and poet Solon argued that the terms of a man's will might be invalidated if he exhibited loss of judgement due to advanced age. Chinese medical texts made allusions to the condition as well, and the characters for "dementia" translate literally to "foolish old person".

Athenians Aristotle and Plato spoke of the mental decay of advanced age, apparently viewing it as an inevitable process that affected all old men, and which nothing could prevent. Plato stated that the elderly were unsuited for any position of responsibility because, "There is not much acumen of the mind that once carried them in their youth, those characteristics one would call judgement, imagination, power of reasoning, and memory. They see them gradually blunted by deterioration and can hardly fulfill their function."

For comparison, the Roman statesman Cicero held a view much more in line with modern-day medical wisdom that loss of mental function was not inevitable in the elderly and "affected only those old men who were weak-willed". He spoke of how those who remained mentally active and eager to learn new things could stave off dementia. However, Cicero's views on aging, although progressive, were largely ignored in a world that would be dominated for centuries by Aristotle's medical writings. Physicians during the Roman Empire, such as Galen and Celsus, simply repeated the beliefs of Aristotle while adding few new contributions to medical knowledge.

Byzantine physicians sometimes wrote of dementia. It is recorded that at least seven emperors whose lifespans exceeded 70 years displayed signs of cognitive decline. In Constantinople, special hospitals housed those diagnosed with dementia or insanity, but these did not apply to the emperors, who were above the law and whose health conditions could not be publicly acknowledged.

Otherwise, little is recorded about dementia in Western medical texts for nearly 1700 years. One of the few references was the 13th-century friar Roger Bacon, who viewed old age as divine punishment for original sin. Although he repeated existing Aristotelian beliefs that dementia was inevitable, he did make the progressive assertion that the brain was the center of memory and thought rather than the heart.

Poets, playwrights, and other writers made frequent allusions to the loss of mental function in old age. William Shakespeare notably mentions it in plays such as Hamlet and King Lear.

During the 19th century, doctors generally came to believe that elderly dementia was the result of cerebral atherosclerosis, although opinions fluctuated between the idea that it was due to blockage of the major arteries supplying the brain or small strokes within the vessels of the cerebral cortex.

In 1907 Alzheimer's disease was described. This was associated with particular microscopic changes in the brain, but was seen as a rare disease of middle age because the first person diagnosed with it was a 50-year-old woman. By 1913–20, schizophrenia had been well-defined in a way similar to later times.

This viewpoint remained conventional medical wisdom through the first half of the 20th century, but by the 1960s it was increasingly challenged as the link between neurodegenerative diseases and age-related cognitive decline was established. By the 1970s, the medical community maintained that vascular dementia was rarer than previously thought and Alzheimer's disease caused the vast majority of old age mental impairments. More recently however, it is believed that dementia is often a mixture of conditions.

In 1976, neurologist Robert Katzmann suggested a link between senile dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Katzmann suggested that much of the senile dementia occurring (by definition) after the age of 65, was pathologically identical with Alzheimer's disease occurring in people under age 65 and therefore should not be treated differently. Katzmann thus suggested that Alzheimer's disease, if taken to occur over age 65, is actually common, not rare, and was the fourth- or 5th-leading cause of death, even though rarely reported on death certificates in 1976.

A helpful finding was that although the incidence of Alzheimer's disease increased with age (from 5–10% of 75-year-olds to as many as 40–50% of 90-year-olds), no threshold was found by which age all persons developed it. This is shown by documented supercentenarians (people living to 110 or more) who experienced no substantial cognitive impairment. Some evidence suggests that dementia is most likely to develop between ages 80 and 84 and individuals who pass that point without being affected have a lower chance of developing it. Women account for a larger percentage of dementia cases than men, although this can be attributed to their longer overall lifespan and greater odds of attaining an age where the condition is likely to occur.

Much like other diseases associated with aging, dementia was comparatively rare before the 20th century, because few people lived past 80. Conversely, syphilitic dementia was widespread in the developed world until it was largely eradicated by the use of penicillin after World War II. With significant increases in life expectancy thereafter, the number of people over 65 started rapidly climbing. While elderly persons constituted an average of 3–5% of the population prior to 1945, by 2010 many countries reached 10–14% and in Germany and Japan, this figure exceeded 20%. Public awareness of Alzheimer's Disease greatly increased in 1994 when former US president Ronald Reagan announced that he had been diagnosed with the condition.

In the 21st century, other types of dementia were differentiated from Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementias (the most common types). This differentiation is on the basis of pathological examination of brain tissues, by symptomatology, and by different patterns of brain metabolic activity in nuclear medical imaging tests such as SPECT and PETscans of the brain. The various forms have differing prognoses and differing epidemiologic risk factors. The causal etiology, meaning the cause or origin of the disease, of many of them, including Alzheimer's disease, remains unclear.

Terminology

Dementia in the elderly was once called senile dementia or senility, and viewed as a normal and somewhat inevitable aspect of aging.

By 1913–20 the term dementia praecox was introduced to suggest the development of senile-type dementia at a younger age. Eventually the two terms fused, so that until 1952 physicians used the terms dementia praecox (precocious dementia) and schizophrenia interchangeably. Since then, science has determined that dementia and schizophrenia are two different disorders, though they share some similarities. The term precocious dementia for a mental illness suggested that a type of mental illness like schizophrenia (including paranoia and decreased cognitive capacity) could be expected to arrive normally in all persons with greater age (see paraphrenia). After about 1920, the beginning use of dementia for what is now understood as schizophrenia and senile dementia helped limit the word's meaning to "permanent, irreversible mental deterioration". This began the change to the later use of the term. In recent studies, researchers have seen a connection between those diagnosed with schizophrenia and patients who are diagnosed with dementia, finding a positive correlation between the two diseases.

The view that dementia must always be the result of a particular disease process led for a time to the proposed diagnosis of "senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type" (SDAT) in persons over the age of 65, with "Alzheimer's disease" diagnosed in persons younger than 65 who had the same pathology. Eventually, however, it was agreed that the age limit was artificial, and that Alzheimer's disease was the appropriate term for persons with that particular brain pathology, regardless of age.

After 1952, mental illnesses including schizophrenia were removed from the category of organic brain syndromes, and thus (by definition) removed from possible causes of "dementing illnesses" (dementias). At the same, however, the traditional cause of senile dementia – "hardening of the arteries" – now returned as a set of dementias of vascular cause (small strokes). These were now termed multi-infarct dementias or vascular dementias.

Society and culture

The societal cost of dementia is high, especially for family caregivers.

Many countries consider the care of people living with dementia a national priority and invest in resources and education to better inform health and social service workers, unpaid caregivers, relatives and members of the wider community. Several countries have authored national plans or strategies. These plans recognize that people can live reasonably with dementia for years, as long as the right support and timely access to a diagnosis are available. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron described dementia as a "national crisis", affecting 800,000 people in the United Kingdom.

There, as with all mental disorders, people with dementia could potentially be a danger to themselves or others, they can be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 for assessment, care and treatment. This is a last resort, and is usually avoided by people with family or friends who can ensure care.

Some hospitals in Britain work to provide enriched and friendlier care. To make the hospital wards calmer and less overwhelming to residents, staff replaced the usual nurses' station with a collection of smaller desks, similar to a reception area. The incorporation of bright lighting helps increase positive mood and allow residents to see more easily.

Driving with dementia can lead to injury or death. Doctors should advise appropriate testing on when to quit driving. The United Kingdom DVLA (Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency) states that people with dementia who specifically have poor short-term memory, disorientation, or lack of insight or judgment are not allowed to drive, and in these instances the DVLA must be informed so that the driving licence can be revoked. They acknowledge that in low-severity cases and those with an early diagnosis, drivers may be permitted to continue driving.

Many support networks are available to people with dementia and their families and caregivers. Charitable organisations aim to raise awareness and campaign for the rights of people living with dementia. Support and guidance are available on assessing testamentary capacity in people with dementia.

In 2015, Atlantic Philanthropies announced a $177 million gift aimed at understanding and reducing dementia. The recipient was Global Brain Health Institute, a program co-led by the University of California, San Francisco and Trinity College Dublin. This donation is the largest non-capital grant Atlantic has ever made, and the biggest philanthropic donation in Irish history.

On 2 November 2020, Scottish billionaire Sir Tom Hunter donated £1 million to dementia charities, after watching a former music teacher with dementia, Paul Harvey, playing piano using just four notes in a viral video. The donation was announced to be split between the Alzheimer's Society and Music for Dementia.