Notes:

· Includes laws which have not yet gone into effect.

· Cannabis remains a Schedule I drug under federal law.

· Some local jurisdictions and Indian reservations have decriminalization or legalization policies separate from the states they are located in.

· Cannabis is illegal in all federal enclaves (other than hemp).

In the United States, the non-medical use of cannabis is decriminalized in 13 states (plus the U.S. Virgin Islands), and legalized in another 17 states (plus Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the District of Columbia), as of April 2021. Decriminalization refers to a policy of reduced penalties for cannabis offenses, typically involving a civil penalty for possession of small amounts (similar to how a minor traffic violation is treated), instead of criminal prosecution or the threat of arrest. In jurisdictions without any penalties the policy is referred to as legalization, although the term decriminalization is sometimes broadly used for this purpose as well.

The movement to decriminalize cannabis in the U.S. emerged during the 1970s, when a total of 11 states decriminalized (beginning with Oregon in 1973). The findings of the 1972 Shafer Commission helped provide momentum to these efforts, as did the 1976 election of President Jimmy Carter (who spoke in favor of decriminalization and endorsed legislation to federally decriminalize). By the end of the decade the tide had turned strongly in the other direction, however, and no state would decriminalize again until 2001.

Efforts to legalize cannabis in the U.S. included a number of ballot initiatives leading up to 2012, but none succeeded. In 2012, success was finally achieved when Washington and Colorado became the first two states to legalize. In 2014 and 2016 several more states followed, and in 2018 Vermont became the first to legalize through an act of state legislature. All jurisdictions that have legalized allow for the commercial distribution of cannabis, except the District of Columbia. All allow for personal cultivation, except Washington State.

At the federal level, cannabis remains prohibited for any use under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. The Justice Department has generally not enforced federal law in states that have legalized cannabis, under the guidance of the Cole Memorandum that was adopted in August 2013. The Cole memo was rescinded by Attorney General Jeff Sessions in January 2018, however, granting U.S. Attorneys greater authority to enforce federal law.

Early use and criminalization

Cannabis was popularized in the U.S. around the mid-19th century, used mostly for its therapeutic benefits in the treatment of a wide range of medical conditions. Its use as medicine continued into the 20th century, but declined somewhat due to a number of different factors. The recreational use of cannabis began to emerge in the early 20th century, introduced to the U.S. by Mexicans fleeing the dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz. As its use spread north of the border, cannabis became stigmatized due to strong anti-Mexican sentiments that had taken hold.

By 1936, the non-medical use of cannabis had been banned in every state. Cannabis was then effectively outlawed at the federal level, following the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Cannabis remained mostly an underground drug until the 1960s, when it found widespread popularity among large numbers of young people and hippies, and was used commonly at protests against the Vietnam War. Cannabis was officially banned for any use with the passage of the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, subsequent to the Supreme Court's overturning of the Marihuana Tax Act in 1969 (in the case Leary v. United States).

History of decriminalization

Supporters of reform begin to organize (1964)

The movement to legalize cannabis in the U.S. was sparked by the 1964 arrest of Lowell Eggemeier, a San Francisco man who walked into the city's Hall of Justice and lit up a joint, requesting to be arrested. As it was a felony to use cannabis in California, Eggemeier was sent to prison where he was held for close to a year. Eggemeier was defended by James R. White, an attorney who had not taken a drug case before nor was he much familiar with cannabis, but took interest in the matter as a devoted civil libertarian (describing himself as "to the right of Barry Goldwater"). While researching the case, White became a strong proponent for the legalization of cannabis, and went on to found LEMAR (shortened version of LEgalize MARijuana) in December 1964. LEMAR was the first organization in the U.S. dedicated to ending cannabis prohibition.

Among those in attendance at the first LEMAR rally was poet Allen Ginsberg, who was staying in Berkeley at the time. Upon returning home to New York City he founded the first East Coast chapter of LEMAR. Ginsberg's activism and writings helped inspire the founding of other LEMAR chapters, including a Detroit chapter by fellow poet John Sinclair. Similar groups advocating for legalization formed across the country in the ensuing years.

By 1971, two main groups supporting cannabis reform had emerged – Amorphia based in San Francisco (founded by Blair Newman) and the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) based in Washington, D.C. NORML was founded by Keith Stroup, an attorney who had previously worked as a researcher for Ralph Nader's National Commission on Product Safety. Drawing upon his experience working with Nader (and his consumer advocate devotees "Nader's Raiders"), Stroup sought to create a consumer advocacy group dedicated to protecting cannabis consumers. He founded NORML in 1970, with the aim of adopting a more professionalized manner of advocacy than other cannabis reform groups (such as Amorphia) more closely associated with the counterculture. Eventually Amorphia was merged into NORML as it ran into financial difficulties, becoming the California chapter of NORML in 1974.

Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (1970)

On October 27, 1970, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon. Known mainly for its drug scheduling provision (contained in Title II, the Controlled Substances Act), the act also included a number of reforms that significantly reduced penalties for certain drug offenses. In particular, it eliminated mandatory minimum drug sentences, made simple possession of all drugs a misdemeanor, and allowed probation and expungement for first-time offenders. Though the act still imposed significant penalties for cannabis (up to a year's imprisonment for possession of small amounts), the change from a felony offense marked a notable liberalization in federal policy. The act also provided a model for state governments to follow, and by 1973 only two states still classified simple possession of cannabis as a felony.

Shafer Commission (1972)

An additional requirement of the Controlled Substances Act was the establishment of a federal commission (formally titled the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse) to study the effects of cannabis use. President Nixon appointed nine of the commission's 13 members, including former Pennsylvania governor Raymond P. Shafer who was designated to serve as chairman. Nixon conveyed to Shafer his strong opposition to the legalization of cannabis, and he advised Shafer to "keep your commission in line" months before the initial report was issued. The release of the 1184-page report would not be to Nixon's liking, however, as the Shafer Commission concluded in March 1972 that cannabis was a relatively benign drug whose dangers had been exaggerated. The report also advised that harsh laws against cannabis did more harm than good, and recommended the removal of criminal penalties for possession and distribution of small amounts of the drug. These findings were influential in persuading 11 states to decriminalize during the 1970s; however, at the federal level no such policy reforms were enacted.

Decriminalization efforts materialize (1970s)

During the early 1970s legislative efforts to reform cannabis laws began to materialize. Among these was a 1972 ballot measure seeking to legalize cannabis in California, spearheaded by the group Amorphia. Proposition 19 – the California Marijuana Initiative – ultimately failed with 33% of the vote. Although it was defeated by a wide margin, supporters of the initiative were encouraged by the results, which provided momentum to other reform efforts in California throughout the decade.

In 1973 Oregon became the first state to decriminalize cannabis, reducing the penalty for up to one ounce to a $100 fine. Other states were reluctant to follow, however, in part due to influence from the Nixon administration which staunchly opposed such reforms. Decriminalization efforts were bolstered by Nixon's resignation in August 1974, however, ushering in the Ford administration and a more tolerant view toward cannabis from the White House. The November 1974 election also brought a wave of new Democrats to state legislatures across the country.

In 1975 a federal committee examined the use of cannabis and other drugs in America, building upon the findings of the Shafer Commission three years earlier. Although the committee – the Domestic Council Drug Abuse Task Force – did not advocate decriminalization outright, it did recommend attention be shifted to more harmful drugs (such as heroin), and concluded that cannabis was the "least serious" drug problem facing the nation. Also in 1975, congressional hearings were held on decriminalizing cannabis for the first time. As these developments provided momentum to reform efforts, a total of five more states (Alaska, Maine, Colorado, California, and Ohio) decriminalized in 1975.

Shortly after Alaska decriminalized in 1975, a ruling by the Supreme Court of Alaska in the case Ravin v. State effectively legalized cannabis in the state. The ruling stemmed from the 1972 arrest of Irwin Ravin, an Alaska resident who allowed himself to be caught possessing cannabis in order to challenge state law. At trial, Ravin's defense argued that the state constitution guaranteed a right to privacy, which extended to the use of cannabis in one's home. In May 1975 the state Supreme Court agreed, legalizing the use, possession, and cultivation of cannabis in amounts for personal use.

In the following years, decriminalization laws passed in Minnesota (1976), Mississippi (1977), New York (1977), North Carolina (1977), and Nebraska (1978). NORML was actively involved in these efforts, lobbying in support of legislation and paying for proponents of decriminalization (including members of the Shafer Commission) to travel to various states to testify.

During the 1970s various cities also decriminalized cannabis, such as Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1972 and Madison, Wisconsin in 1977. Additionally, San Francisco residents approved Proposition W in 1978, a non-binding measure directing city law enforcement to "cease the arrest and prosecution of individuals involved in the cultivation, transfer, or possession of marijuana". Mayor George Moscone was assassinated a few weeks later, however, and the initiative was subsequently disregarded.

Carter administration and resignation of Peter Bourne (1976 to 1978)

As decriminalization efforts continued to progress during the 1970s, many supporters of reform – including Stroup himself – believed federal decriminalization was just around the corner. This optimism was particularly buoyed by the 1976 election of President Jimmy Carter, who spoke in favor of decriminalization during his presidential campaign (earning him the support of Stroup and NORML). Carter was urged to speak in support of decriminalization by Peter Bourne, an Atlanta physician who grew close to Carter during his time as Georgia governor. Upon being elected president, Carter gave Bourne an office in the West Wing and the official title "Special Assistant to the President for Drug Abuse". From this position, Bourne continued to advocate for cannabis decriminalization, while also developing a close relationship with Stroup and NORML. In August 1977, the White House issued its first official position paper on drug policy, which Stroup helped draft. Included in the paper was a call for up to one ounce of cannabis to be decriminalized at the federal level.

By the fall of 1977, the relationship between Bourne and Stroup had begun to sour. The Carter administration was providing helicopters to the government of Mexico, which were being used to eradicate cannabis crops by spraying the herbicide paraquat. Stroup argued that these crops could find their way into the U.S. and harm American consumers of the drug. Simultaneously, Stroup was growing frustrated that the administration was not doing more to support the decriminalization policies that it had previously championed. By March 1978 Stroup's anger had reached a boiling point, as Bourne and the administration continued to support paraquat spraying in the face of growing public opposition to the practice (and emerging evidence that it posed a serious health risk). Stroup decided to take matters into his own hands, contacting reporter Gary Cohn and informing him that Bourne had used cocaine at the annual Christmas party hosted by NORML a few months earlier. Although this information was not immediately published, in July 1978, when Bourne was in the midst of a scandal over writing an illegal prescription, the cocaine revelation came to light. Faced with two simultaneous scandals of illegal prescription writing and drug use, Bourne resigned from his position.

The resignation of Peter Bourne was considered a significant blow to decriminalization efforts in a number of ways. First, there were no advisers pushing Carter to support decriminalization anymore, as Bourne's successor Lee Dogoloff was not particularly sympathetic to the cause. Also, the embarrassment of the Bourne scandal, along with allegations of drug use that had been made against other members of the administration, made decriminalization a much more politically sensitive topic that Carter thus sought to avoid. It was not just the Carter administration that had been damaged from the incident, however. Stroup's role in the scandal proved to be a major embarrassment for NORML, and by December 1978 led to his resignation, due to the anger and distrust that his actions had caused. The departure of Stroup also caused NORML to lose the support of some of its top donors, including its largest benefactor the Playboy Foundation.

Parent revolution, Reagan years, and recriminalization (late 1970s through 80s)

By the end of the 1970s, efforts to decriminalize cannabis had stalled at both the state and federal level. Although the fallout of the Bourne scandal played a significant role, there was another factor at play in bringing about this shift. A movement of anti-drug parent activists was on the rise, driven by a spike in adolescent drug use and the wide availability of paraphernalia products for sale (some of which resembled children's toys). The movement sprang out of Atlanta in 1976, as a number of support groups were formed for parents concerned about teen drug use. The groups soon spread across the country and began turning attention to legislative affairs such as halting decriminalization efforts and passing anti-paraphernalia laws. Momentum continued to grow as President Reagan took office in 1981 and first lady Nancy Reagan strongly embraced the cause. In the span of a few years the movement to decriminalize had effectively been quashed.

During the Reagan years, the federal war on drugs was significantly ramped up, and a number of states acted to increase penalties for drug crimes. Meanwhile, NORML struggled to regain the influence that it once held, as it dealt with severe decreases in funding and membership, and underwent frequent changes to organizational leadership. In 1985 part of NORML was split off to found the Drug Policy Foundation, which was then merged with the Lindesmith Center to become the Drug Policy Alliance in 2000. Members of NORML further split off in 1995 to found the Marijuana Policy Project.

In 1990, Alaska voters approved a ballot initiative to recriminalize cannabis, overriding the court decision that legalized cannabis 15 years earlier. Also in 1990, the Solomon–Lautenberg amendment was enacted at the federal level, leading many states to further criminalize cannabis by passing "Smoke a joint, lose your license" laws. These laws imposed mandatory driver's license suspensions of at least six months for committing any type of drug offense (regardless of whether any motor vehicle was involved) including the simple possession of cannabis. As of 2020 only four states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and Texas) continue to have such laws in effect.

Second wave of decriminalization begins (2001)

After Nebraska decriminalized cannabis in 1978, no other state would follow for over two decades, until Nevada decriminalized in 2001. In subsequent years a number of major cities decriminalized cannabis or made enforcement of cannabis laws the lowest priority. Among the first major cities to pass such measures were Seattle (2003), Oakland (2004), Denver (2005), and San Francisco (2006). In the years that followed reform efforts continued to gain steam, with decriminalization laws passing in Massachusetts (2008), Connecticut (2011), Rhode Island (2012), Vermont (2013), the District of Columbia (2014), Maryland (2014), Missouri (2014), the U.S. Virgin Islands (2014), Delaware (2015), Illinois (2016), New Hampshire (2017), New Mexico (2019), North Dakota (2019), Hawaii (2019), and Virginia (2020). As of 2021 thirteen states have decriminalization policies in effect, and an additional twelve states have decriminalized that later legalized.

State recreational legalization begins (2012)

Prior to 2012, ballot initiatives seeking to legalize cannabis were attempted in a number of states but none succeeded. Among these attempts were California in 1972 (33% support), Oregon in 1986 (26%), Alaska in 2000 (41%), Nevada in 2002 (39%), Alaska in 2004 (44%), Colorado in 2006 (46%), Nevada in 2006 (46%), and California in 2010 (47%).

In 2012, success was finally achieved for legalization advocates in the states of Washington and Colorado, when voters approved Initiative 502 and Amendment 64. In subsequent years, cannabis was legalized by ballot measure in Oregon (2014), Alaska (2014), the District of Columbia (2014), California (2016), Nevada (2016), Maine (2016), Massachusetts (2016), Michigan (2018), Arizona (2020), Montana (2020), and New Jersey (2020), and by an act of legislature in Vermont (2018), the Northern Mariana Islands (2018), Guam (2019), Illinois (2019), New York (2021), Virginia (2021), and New Mexico (2021). In all of these jurisdictions, commercial distribution of cannabis has been legalized except for the District of Columbia, personal cultivation has been legalized except for Washington State and New Jersey, public consumption is prohibited except for New York (though on-premises consumption is allowed in some jurisdictions), and use by individuals under 21 years old is prohibited.

Federal response

After the first states legalized in 2012, uncertainty remained over how the federal government would respond. Seeking to clarify, the Justice Department issued the Cole Memorandum in August 2013, which specified eight conditions under which enforcement of federal law would be prioritized (such as distribution of cannabis to minors or diversion across state borders). Aside from these situations, the memo generally allowed for the commercial distribution of cannabis in states where such activity had been legalized. The Cole memo was only a non-binding set of guidelines for federal prosecutors, however, and therefore did not carry the force of law.

Although the Cole memo was adhered to by federal prosecutors, members of Congress sought the assurances that a legally binding act of legislation could provide. The McClintock–Polis amendment was hence introduced in the U.S. House (as an attachment to the Commerce, Justice, and Science appropriations bill for fiscal year 2016) to prohibit the Justice Department from spending funds to interfere with the implementation of state cannabis laws (regarding both recreational and medical use). The McClintock–Polis amendment was narrowly defeated on June 3, 2015, by a vote of 206 to 222.

The Cole memo remained in effect until January 2018 when it was rescinded by Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The intended impact of the rescission was not immediately made clear, however, in regards to what kind of crackdown (if any) on the states would be forthcoming. In response to the memo's rescission, the STATES Act was introduced in Congress (upon consultation with President Donald Trump) to enshrine into law protections that the Cole memo previously provided. President Trump confirmed to reporters his intent to sign the STATES Act should it be approved by Congress.

On June 20, 2019, four years after the McClintock–Polis amendment was defeated, a similar amendment protecting state-legal cannabis activities was approved by the House. The amendment, introduced by Rep. Earl Blumenauer and attached to the CJS appropriations bill for fiscal year 2020, passed by a 267–165 vote.

On September 25, 2019, the House of Representatives approved the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act by a 321–103 vote. The bill, which seeks to improve access to banks for cannabis businesses, is the first standalone cannabis reform bill approved by either chamber of Congress.

On November 20, 2019, the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act passed the House Judiciary Committee by a 24–10 vote. It was the first time a federal bill to legalize cannabis had ever passed a congressional committee. The MORE Act passed the full House of Representatives on December 4, 2020, by a vote of 228–164.

Arguments in support of reform

In 1972, President Richard Nixon commissioned the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse to produce an in-depth report on cannabis. The report, "Marijuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding", found cannabis prohibition constitutionally suspect and stated regardless of whether the courts would overturn prohibition of cannabis possession, the executive and legislative branches have a duty to obey the Constitution. "It's a matter of individual freedom of choice", said ACLU President Nadine Strossen in an interview. "Does that mean they should do it? Not necessarily, not any more than somebody should smoke or drink or eat McDonald's hamburgers."

U.S. attitudes toward legalization and decriminalization started dramatically liberalizing in the 1990s, and a 2018 study in Social Science Research found that the main drivers of these changes in attitudes were a decline in perception of the riskiness of marijuana, changes in media framing of marijuana, a decline in overall punitiveness, and a decrease in religious affiliation.

Potential medical benefits of marijuana

Marijuana (cannabis) is an herb drug, which contains a very active component delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). For thousands of years, it was used for medical purposes in many different parts of the world. Recent studies also agreed that THC had great potential benefits for medical purposes. A number of patients who have HIV, multiple sclerosis (MS), neuropathic chronic pain, and cancer were under medical marijuana treatment. The treatments could either be smoke on cannabis or oral preparations, which were synthetic THC and synthetic equivalent.

According to Medical Uses of Marijuana (Cannabis sativa), patients with HIV reported that the drug reduced mixed neuropathic pain more significantly in comparison to other placebo drugs. They addressed that there was a minimum of 30% pain reduction when they were under smoked medical marijuana treatment. Furthermore, under the same type of treatment, most of the patients with multiple sclerosis showed dramatic improvements on their symptoms. After the treatment, their handwriting was much clearer and head tremor pain was less than the samples taken before the treatment. In addition, many patients that associated with chronic pain, multiple sclerosis were also under marijuana oral preparation treatment. Patients treated with dronabinol, a synthetic THC, reported that there was a 50% pain reduction compared to 30% that was experienced when given the placebo. Furthermore, cancer treatment involving chemotherapy also agreed that dronabinol had significant benefits on delaying nausea and vomiting for patients. However, medical marijuana treatments are not for everyone and it may cause adverse side effects for others. Overall, the potential long-term side effects of medical marijuana are not yet fully classified. As a result, further studies must carry out to fully understand the benefits as well as adverse psychiatric and medical side effects of the drug.

Economic arguments

Many proponents of cannabis decriminalization have argued that decriminalizing cannabis would largely reduce costs of maintaining the criminal justice and law enforcement systems, while legalizing cannabis to allow the cultivation and sale would generate a substantial amount of income from taxing cannabis sales. In Colorado, in June 2020, monthly marijuana sales reached $199 million.

In 2005, more than 530 distinguished economists called for the legalization of cannabis in an open letter to President Bush, Congress, Governors, and state legislatures. The endorsers included conservative economist Milton Friedman and two other Nobel Prize-winners, Dr. George Akerlof and Dr. Vernon Smith.

The letter stated, among other things, "We, the undersigned, call your attention to the attached report [which]... shows that marijuana legalization — replacing prohibition with a system of taxation and regulation — would save $7.7 billion per year in state and federal expenditures on prohibition enforcement and produce tax revenues of at least $2.4 billion annually if marijuana were taxed like most consumer goods. If, however, marijuana were taxed similarly to alcohol or tobacco, it might generate as much as $6.2 billion annually...."

We therefore urge the country to commence an open and honest debate about marijuana prohibition. We believe such a debate will favor a regime in which marijuana is legal but taxed and regulated like other goods. At a minimum, this debate will force advocates of current policy to show that prohibition has benefits sufficient to justify the cost to taxpayers, foregone tax revenues, and numerous ancillary consequences that result from marijuana prohibition."

The report also projected the tax revenues from decriminalization, by state.

Other arguments point out that the funds saved from cannabis decriminalization could be used to enforce laws for other, more serious and violent crimes.

In 1988, Michael Aldrich and Tod Mikuriya published "Savings in California Marijuana Law Enforcement Costs Attributable to the Moscone Act of 1976" in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. The study estimated California saved almost one billion dollars in a twelve-year period between 1976 and 1988, as a result of the Moscone Act of 1976 that decriminalized cannabis.

In 2003, the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) published "Economic Costs of Drug Abuse", which stated without separately analyzing cannabis related costs, the United States was spending $12.1 billion on law enforcement and court costs, and $16.9 billion in corrections costs, totaling $29 billion.

In 2004, Scott Bates of the Boreal Economic Analysis & Research center prepared a study for Alaskans for Rights & Revenues entitled "The Economic Implications of Marijuana Legalization in Alaska." The study estimated the Alaskan government was spending $25–30 million per year enforcing cannabis prohibition laws. The study found if the purchase of cannabis were to be taxed as a legal commodity, tax revenues would increase by about $10–20 million per year, making $35–50 million per year in funds available.

In 2006, a study by Jon Gettman entitled "Marijuana Production in the United States" was published in the Bulletin of Cannabis Reform. The report states cannabis is the top cash crop in 12 states, is one of the top three cash crops in 30 states, and is one of the top five cash crops in 39 states. Gettman estimated the value of U.S. cannabis production at $35.8 billion, which is more than the combined value of corn and wheat. Furthermore, the report states according to federal estimates, eradication efforts have failed to prevent the spread of cannabis production, as cannabis production has increased tenfold in the past 25 years.

In 2006, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime released the 2006 World Drug Report, which stated the North American cannabis market is estimated to be worth anywhere from $10 billion to $60 billion annually. That same study also indicated that the mountainous regions in Appalachia, and the rural areas of the West Coast are ideal for growing cannabis. Allowing farmers there to grow cannabis openly would both provide jobs and reduce the need for expensive federal welfare payments to those areas, which are disproportionately dependent on welfare.

In 2006, a study by the University of California, Los Angeles found California has saved $2.50 for every dollar invested into Proposition 36, which decriminalized cannabis and other drug possession charges by allowing out patient treatment programs instead of incarceration. In the first year the proposition was enacted (2001), California reportedly saved $173 million, which is likely a result of fewer drug offenders in prison. In the five years after the program was enacted, 8,700 fewer people are in prison for drug offenses.

Since cannabis is illegal in the United States, this policy has led to penalties for simple use and possession. Despite these penalties, users continue to find themselves in trouble with the law. The Connecticut Law Revision Commission made the following evaluation: "(1) the costs of arresting and prosecuting marijuana offenders were significantly lower in states that had done away with criminal penalties for possessing small amounts; (2) there was a greater increase in marijuana use in states that continue to treat possession as a crime than in states that treated it as a civil offense; (3) easing the penalties for marijuana did not lead to a substantial increase in the use of either alcohol or hard drugs."

Reduction of income earned by organized crime

The Drug Enforcement Administration has reported that cannabis sales and trafficking support violent criminal gangs. Proponents of fully decriminalizing cannabis to allow the regulated cultivation and sale of cannabis, including Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, argue that fully decriminalizing cannabis would largely decrease financial gains earned by gangs in black market cannabis sales and trafficking.

Displacement of alcohol consumption

A study in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management by Mark Anderson and Daniel Reese indicated that increased marijuana use in California is a substitute for alcohol. This research showed that participants frequently choose marijuana over other substances. They reported that over 41 percent of the people said that they prefer to use marijuana instead of alcohol. Some of the main reasons for this substitute were 'less withdrawal', 'fewer side-effects' and 'better symptom management'.

California Secretary of State's office said that on September 7, 2010 the beer lobby donated $10,000 to Public Safety First, a group which opposed the passage of Proposition 19 to legalize cannabis.

Reduction of subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs

The Marijuana Policy Project argues that:

Research shows that the actual "gateway" is the illegal drug market. The World Health Organization noted that any gateway effect associated with marijuana use may actually be due to marijuana prohibition because "exposure to other drugs when purchasing cannabis on the black-market increases the opportunity to use other illicit drugs." A study comparing experienced cannabis users in Amsterdam, where adults can purchase small amounts of cannabis from regulated businesses, with similarly experienced cannabis users in San Francisco, where non-medical possession and sale of cannabis remains completely illegal, bolstered this hypothesis: The San Francisco cannabis users were twice as likely to use crack cocaine as their Dutch counterparts, more than twice as likely to use amphetamines, and five times as likely to be current users of opiates.

Health effects of cannabis

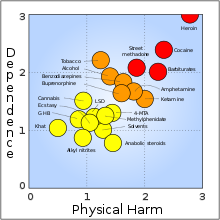

Cannabis has been subject to many studies over the past century. Studies acknowledge that cannabis can in rare cases cause adverse reactions, but is generally safer than any commonly consumed drug such as alcohol, tobacco and pharmaceuticals. In fact, in an article published in The Lancet journal about the adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use, Professors Hall and Degenhardt clearly stated that "the public health burden of cannabis use is probably modest compared with that of alcohol, tobacco, and other illicit drugs." Psychopharmacologist and former UK government drugs advisor David Nutt argues, though he is against full declassification, that the harm caused by cannabis is far less than that caused by alcohol or tobacco, which, if they were invented today "would be illegal."

Reduction in prison overcrowding and strain on the criminal justice system

Supporters of decriminalization and decarceration in the United States argue that if cannabis were to be legalized it would reduce the number of non violent offenders in prison making room for the incarceration of more violent offenders as well as easing the current strain that the large number of cannabis possession cases have on the criminal justice system. They also propose that it would also save taxpayers the cost of incarceration for these non violent offenders.

In the 1970s, there were just under 200,000 criminals serving time in state and federal prisons and an upwards of 750,000 in local jails for marijuana related crimes. Today there are over 1.5 million Americans serving time in an institution. If marijuana was decriminalized, these numbers were further be reduced again to below 700,000 inmates and save the taxpayers billions of dollars per year.

The United States spends an estimated $68 billion per year on prisoners with a third of that number have been incarcerated for non-violent drug crimes including a sixth of those numbers as marijuana drug related offenses. A reduction in the prison population due to decriminalizing marijuana could save an average of $11.3 billion per year on courts, police, prison guards and other related expenses.

Success of progressive drug policies adopted in other countries

Studies on decriminalization of marijuana in Portugal have indicated it to be a "huge success". Drug use rates in Portugal were found to be dramatically lower than the United States with decriminalization enacted.

Teenage use of marijuana in the Netherlands where it is sold legally and openly is lower than in the United States.

Uruguay became the first country in the world to completely legalize cannabis in 2013.

Individual freedom

Some people are in favor of decriminalization and legalization of marijuana simply for the moral stance that individuals' freedom for property rights should be respected. This view is generally held in libertarian politics. This view is that regardless of any health effects of someone's lifestyle choice, if they are not directly harming anyone else or their property then they should be free to do what they want. Many people who support drug freedom policies may personally be strongly against drug use themselves but still want to protect the freedom of others to do so.

Investors

In order to effectively campaign to legalize recreational cannabis use, millions of dollars have been spent to lobby for this reform. George Soros is a billionaire hedge fund manager that has spent over $25 million on marijuana reform efforts. In 2010 Soros wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal citing the fact that African Americans are no more likely than other Americans to use marijuana but are far more likely to be arrested for possession.

Soros efforts to reform marijuana laws were predated by fellow billionaire, the late Peter Lewis. Lewis was the former chairman of Progressive Insurance and died November 23, 2013. Lewis is considered to be the most high-profile billionaire backer of drug reform and the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) estimated that Lewis had spent well over $40 million funding the cause since the 1980s. During the November 2012 election, he spent almost $3 million helping secure the passage of marijuana legalization bills in both Washington State and Massachusetts. The list of capitalists who have joined Soros and Lewis in the cause of Marijuana reform include John Sperling, who is the founder of the University of Phoenix and George Zimmer who is the founder and former CEO of Men's Wearhouse. Sperling donated $70,000 to support marijuana law reform in Oregon, and Zimmer contributed $20,000 to advocate for marijuana decriminalization in California.

These capitalists have helped pave the way for a new type of business with special interests in the cannabis industry. The ArcView Group was founded in 2010 by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and marijuana advocates Troy Dayton and Steve DeAngelo. Their company teams up angel investors with companies that produce cannabis products and it's been one of the major sources of startup revenue for cannabis-related companies. This company has contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to educational reform groups like the Students for Sensible Drug Policy and a pro-legalization PAC run by the Marijuana Policy Project.

The ACLU and NAACP

The ACLU takes a firm position that decriminalizing cannabis will keep tens of thousands of people from entering into the criminal justice system as police efforts result in both unnecessary arrests and the enforcement of marijuana laws wastes billions of tax payers' dollars. They affirm that removing criminal penalties for marijuana offenses will therefore reduce the U.S. prison population and more effectively protect the public and promote public health. One of the reasons that the ACLU has been such a strong supporter of drug decriminalization is that according to their research drug related arrests have largely driven America's incarceration rate to unacceptable levels. Drug offenders account for over 500,000 of the more than 2 million people in America's prisons and jails, and drug offenses combined with failed drug tests account for a significant number of those returning to prison for parole and probation violations. Between 2001 and 2010, there were over 7 million pot arrests in the U.S. and of these arrests 88% were for simply having marijuana. These marijuana related arrests now account for over half of all drug related arrests in the United States. These arrests tend to be racially imbalanced as a black person is 3.73 times more likely to be arrested than a white person for marijuana related charges, despite research that suggests fairly equal usage rates between the two races. The ACLU is further troubled by the amount of money that is spent annually to enforce marijuana laws as they claim that over 3 billion dollars are spent every year by states to enforce marijuana regulation, while the drug's availability has not declined. The ACLU claims that over 50% of Americans support marijuana legalization and they are advocating for the legalization of Cannabis through the Criminal Law Reform Project. They believe that the resources that are spent on enforcing marijuana law could be better invested in our communities through education and job training.

The NAACP has taken a similar stance and has cited the same data used by the ACLU. The NAACP has been strong supporters of the Respect State Marijuana Laws Act – H.R. 1523 and has reached out to members of congress to get this act passed. This act is designed to decrease penalties for low-level marijuana possession and supports prohibiting federal enforcement of marijuana laws in states which have lesser penalties.

Racial bias

There are claims of historical evidence showing that a significant reason for marijuana ban by US government was political and racist in nature, aimed to suppress black and Mexican minorities. A quote from a 1934 newspaper reads:

"Marihuana influences Negroes to look at white people in the eye, step on white men's shadows and look at a white woman twice."

Former Nixon aide and Watergate co-conspirator John Ehrlichman said the following to author Dan Baum in an interview regarding the politics of drug prohibition:

"The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I'm saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did."

Loo, Hoorens, Hof and Kahan also talked about this issue in their book 'Cannabis policy, implementation and outcomes'. According to them, statistics show that controlling cannabis use leads in many cases to selective law enforcement, which increases the chances of arresting people from certain ethnicities. For example, while Blacks and Hispanics constitute about 20% of cannabis users in the US, they accounted for 58% of cannabis offenders sentenced under federal law in 1994.

In 2013, the ACLU published a report titled "The War on Marijuana in Black and White". The report found that despite marijuana use being roughly equal between blacks and whites, blacks are 3.73 times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession.

Tough marijuana policies have also resulted in the disproportionate mass deportation of over 250,000 legal immigrants in the United States. In a 93-page report, Human Rights Watch described the effects of stringent marijuana and other drug policies on US immigrant families.

Occupational health and safety

Since cannabis is still recognized as an illegal substance under federal law, each state has their own rules and regulations with regards to cannabis cultivation. As this is still a relatively new industry, there are challenges in formulating safety regulations; much discrepancy exists between state regulations and federal regulations with respect to legal agricultural practices. Since there are no federal regulations on pesticide use in cannabis cultivation, none are registered for use in the United States, and illegal pesticide use is common. Samples purchased by law enforcement in California, have for example detected pesticide residues present on cannabis product for sale to the public. Workers risk exposure to THC, pesticides, and fertilizers through respiratory, dermal, and ocular pathways. One grower was reported to have developed pruritus and contact uticaria from simply handling the plants, after being tolerant to moderate use before. Other allergic reactions, such as asthma, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and cutaneous symptoms have been reported. Workers are also at risk of overexposure to UV rays from lamps used, and overexposure to carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides from devices used to promote cannabis growth. Cuts, nicks, and scrapes are also a risk during the harvest of cannabis buds. A survey completed by the CDPHE has found that while workers valued safety, 46% of them never received any training in safety procedures and protocols. Washington and Colorado have published valuable state guides with state regulations and best practices.

Environmental safety

Pesticide Use: "The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates pesticide use on agricultural crops, but has not tested any pesticides for use on marijuana because it is still illegal at the federal level. Given what is known about the chemicals commonly used on marijuana plants, that means a potential public health hazard for the millions of people who smoke or consume marijuana, as well as those who work at the grow operations."

According to a 2013 study published in the Journal of Toxicology that assessed quantities of pesticides marijuana smokers were exposed to, it was found that "recoveries of residues were as high as 69.5% depending on the device used and the component investigated, suggesting that the potential of pesticide and chemical residue exposures to cannabis users is substantial and may pose a significant toxicological threat in the absence of adequate regulatory frameworks". Marijuana also differs from other agricultural products in that it can not be rinsed with water as the product is traditionally dried or cured.

The following six pesticides are considered highly toxic but commonly used on marijuana crops:

- Myclobutanil (fungicide): Developmental and reproductive toxin; Not allowed in WA or CO, found on tested samples in CO and OR

- Pyrethrin (insecticide): Carcinogen; Approved in CO and WA

- Fenoxycarb (insecticide): Carciniogen, cholinesterase inhibitor; not allowed in WA

- Thiophanate-methyl (fungicide): Carcinogen; Not allowed in WA or CO, found on tested samples in CO.

- Avermectin- (insectide): Developmental and reproductive toxin: not allowed in CO or WA, but found on tested samples in CO

- Bifenthrin (insectide): Developmental and reproductive toxin, possible carcinogen; Not allowed in CO or WA, but found on tested samples in CO and OR

Myclobutanil is the active chemical compound in the pesticide Eagle 20EW, the use of which is prohibited in Colorado. However, Eagle 20EW is still a commonly used pesticide. The federal limit, set by the EPA, for the amount in myclobutanil residue on lettuce is 0.3 parts per million – yet the amount tested on marijuana in Denver has at times reached 23.83 parts per million.

A complete list of pesticides allowed for use on cannabis in Colorado approved by the Colorado Department of Agriculture is available here, and for Washington State as approved by the Washington State Department of Agriculture is available here.

Energy Use: Indoor marijuana cultivation is highly energy intensive. It is estimated that the industry accounts for 1% of all the nation's electricity use, which is six times the amount the pharmaceutical industry consumes. In terms of emissions, it is estimated that fifteen million metric tons of carbon are produced by the industry annually. Legalization would require those in the industry to meet long standing statutes such as the Clean Air Act, as well as give the opportunity to states to enforce provisions on energy use through conditions of licensure. For example, in the city of Boulder, Colorado, marijuana businesses are required to utilize renewable energy to offset 100% of their electricity consumption.

Ecosystem: A single mature marijuana plant can consume 23 liters of water a day, compared to 13 liters for a grape plant. Historically, many outdoor cultivators have used illegal river and lake diversions to irrigate crops. These diversions have led to dewatering of streams and rivers which is well documented in areas of Northern California. As with any other agricultural crop, increase in demand leads to increased clear cutting of forests which can increase erosion, habitat destruction, and river diversion. Legalization and subsequent regulation could mitigate such issues.

Arguments in opposition to reform

Subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs

In 1985, Gabriel G. Nahas published Keep Off the Grass, which stated that "[the] biochemical changes induced by marijuana in the brain result in drug-seeking, drug taking behavior, which in many instances will lead the user to experiment with other pleasurable substances. The risk of progression from marijuana to cocaine to heroin is now well documented."

In 1995, Partnership for a Drug-Free America with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the White House Office of Drug Control Policy launched a campaign against cannabis use citing a Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) report, which claimed that cannabis users are 85 times more likely than non-cannabis users to try cocaine. Additionally, some research suggests that marijuana use is likely to precede the use of other licit and illicit substances. However, an article published in The Activist Guide by John Morgan and Lynn Zimmer entitled "Marijuana's Gateway Myth", claims CASA's statistic is false. The article states:

The high risk-factor obtained is a product not of the fact that so many marijuana users use cocaine but that so many cocaine users used marijuana previously. It is hardly a revelation that people who use one of the least popular drugs are likely to use the more popular ones — not only marijuana, but also alcohol and tobacco cigarettes. The obvious statistic not publicized by CASA is that most marijuana users — 83 percent — never use cocaine.

Multiple opponents of cannabis decriminalization have claimed increased cannabis use results in increased abuse of other illicit drugs. However, multiple studies have found no evidence of a correlation between cannabis use and the subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs.

In 1997, the Connecticut Law Revision Commission examined states that had decriminalized cannabis and found decriminalizing small amounts of cannabis has no effect on subsequent use of alcohol or "harder" illicit drugs. The study recommended Connecticut reduce cannabis possession of one ounce or less for adults age 21 and over to a civil fine.

In 1999, a study by the Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health at the Institute of Medicine entitled "Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base", found no evidence of a link between cannabis use and the subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs on the basis of its particular physiological effect.

In December 2002, a study by RAND investigating whether cannabis use results in the subsequent use of cocaine and heroin was published in the British Journal of Addiction. The researchers created a mathematical model simulating adolescent drug use. National rates of cannabis and hard drug use in the model matched survey data collected from representative samples of youths from across the United States; the model produced patterns of drug use and abuse. The study stated:

The people who are predisposed to use drugs and have the opportunity to use drugs are more likely than others to use both marijuana and harder drugs ... Marijuana typically comes first because it is more available. Once we incorporated these facts into our mathematical model of adolescent drug use, we could explain all of the drug use associations that have been cited as evidence of marijuana's gateway effect ... We've shown that the marijuana gateway effect is not the best explanation for the link between marijuana use and the use of harder drugs.

In 2004, a study by Craig Reinarman, Peter D. A. Cohen, and Hendrien L. Kaal entitled "The Limited Relevance of Drug Policy: Cannabis in Amsterdam and in San Francisco", was published in the American Journal of Public Health. The study found no evidence that the decriminalization of cannabis leads to subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs. The study also found the mean age at onset of cannabis use and the mean age of cannabis users are both higher in Amsterdam than in San Francisco.

In 2006, the Karolinska Institute in Sweden used twelve rats to examine how adolescent use of cannabis affects subsequent abuse of other illicit drugs. The study gave six of the twelve "teenage" rats a small dose of THC, reportedly equivalent to one joint smoked by a human, every three days. The rats were allowed to administer heroin by pushing a lever and the study found the rats given THC took larger doses of heroin. The institute examined the brain cells in the rats and found THC alters the opioid system that is associated with positive emotions, which lessens the effects of opiates on rat's brain and thus causes them to use more heroin. Paul Armentano, policy analyst for NORML, claimed because the rats were given THC at the young age of 28 days, it is impossible to extrapolate the results of this study to humans.

In December 2006, a 12-year gateway drug hypothesis study on 214 boys from ages 10–12 by the American Psychiatric Association was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The study concluded adolescents who used cannabis prior to using other drugs, including alcohol and tobacco, were no more likely to develop a substance abuse disorder than subjects in the study who did not use cannabis prior to using other drugs.

In September 2010, a study from the University of New Hampshire examined survey data from 1,286 young adults who had attended Miami-Dade County Public Schools in the 1990s and found the association between teenage cannabis use and other illicit drug abuse by young adults was significantly diminished after controlling for other factors, such as unemployment. They found that after young adults reach age 21, the gateway effect subsides entirely.

Increased crime

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has claimed that cannabis leads to increased crime in the pamphlet entitled "Speaking Out Against Drug Legalization"

In 2001, a report by David Boyum and Mark A.R. Kleiman entitled "Substance Abuse Policy from a Crime-Control Perspective" found the "high" from cannabis is unlikely to trigger violence and concluded:

Making marijuana legally available to adults on more or less the same terms as alcohol would tend to reduce crime, certainly by greatly shrinking the illicit market and possibly by reducing alcohol consumption via substitution if smoking marijuana acts, on balance, as a substitute for drinking alcohol rather than a complement to it since drinking seems to have a greater tendency to unleash aggression than does cannabis use.

In 2004, a study by Scott Bates from the Boreal Economic Analysis & Research center entitled "The Economic Implications of Marijuana Legalization in Alaska", was prepared for Alaskans for Rights & Revenues. The study found there was no link between cannabis use and criminal behavior.

A 2014 study published in PLoS ONE found that not only did the legalization of Medical cannabis not increase violent crime, but that a 2.4% reduction in homicide and assault was found for each year the law was in effect.

Increased cannabis usage

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has claimed that cannabis decriminalization will lead to increased cannabis use and addiction in the un-sourced pamphlet entitled "Speaking Out Against Drug Legalization". The pamphlet states in 1979, after 11 states decriminalized private cannabis use, cannabis use among 12th grade students was almost 51 percent and in 1992, when stricter cannabis laws were put in place, the usage rate reduced to 22 percent. The pamphlet also states that when Alaska decriminalized cannabis in 1975, the cannabis use rate among youth eventually rose to twice the national average youth usage rate nationwide; even though the law did not apply to anyone under the age of 19, the pamphlet explains this is why Alaska re-criminalized cannabis in 1990. Save Our Society From Drugs (SOS) has also stated that decriminalizing cannabis will increase usage among teenagers, citing an increase in Alaskan youth cannabis usage when cannabis was decriminalized. However, cannabis use rose in all states in the 1970s, and the DEA does not say whether or not Alaska started out higher than the national average. Following decriminalization, Alaska youth had lower rates of daily use of cannabis than their peers in the rest of the US.

In 1972, President Richard Nixon commissioned the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse to produce an in-depth report on cannabis. The report, entitled "Marijuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding", reviewed existing cannabis studies and concluded that cannabis does not cause physical addiction.

Studies conducted in Oregon, California, and Maine within a few years of decriminalization found little increase in cannabis use, compared to the rest of the country; "The most frequently cited reasons for non-use by respondents was 'not interested,' cited by about 80% of non-users. Only 4% of adults indicated fear of arrest and prosecution or unavailability as factors preventing use."

In 1997, the Connecticut Law Revision Commission examined states that had decriminalized cannabis and found any increase in cannabis usage was less than the increase in states that have not decriminalized cannabis; furthermore, the commission stated "the largest proportionate increase [of cannabis use] occurred in those states with the most severe penalties." The study recommended Connecticut reduce cannabis possession of 28.35 grams (one ounce) or less for adults age 21 and over to a civil fine.

In 1999, a study by the Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health at the Institute of Medicine entitled "Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base", concluded "there is little evidence that decriminalization of marijuana use necessarily leads to a substantial increase in marijuana use."

In 2001, a report by Robert MacCoun and Peter Reuter entitled "Evaluating alternative cannabis regimes", was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry. The report found there was no available evidence cannabis use would increase if cannabis were decriminalized.

In 2004, a study entitled "The Limited Relevance of Drug Policy: Cannabis in Amsterdam and in San Francisco", found strict laws against cannabis use have a low impact on usage rates.

Increased safety concerns

Studies conducted following the legalization of cannabis in Washington and Colorado show that driving under the effects of marijuana increases a driver's likelihood of getting in accident by 100% in comparison to sober drivers. They also suggest that increased use will lead to higher workplace accidents, with employees who tested positive for cannabis being 55% more likely to get in an accident, and 85% more likely to get injured on the job.

Big business

In a Huffington Post interview, Mark Kleiman, the "Pot Czar" of Washington state, said he was concerned that the National Cannabis Industry Association would favor profits over public health. He also said that it could become a predatory body like the lobbying arms of the tobacco and alcohol industries. Kleiman said: "The fact that the National Cannabis Industry Association has hired itself a K Street suit [lobbyist] is not a good sign."

Advocacy

Several U.S.-based advocate groups seek to modify the drug policy of the United States to decriminalize cannabis. These groups include Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, The Drug Policy Alliance, the Marijuana Policy Project, NORML, Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis, and Americans for Safe Access. There are also many individual American cannabis activists, such as Jack Herer, Paul Armentano, Edward Forchion, Jon Gettman, Rob Kampia, and Keith Stroup; Marc Emery, a well-known Canadian activist, has supported cannabis activism in the U.S. among other countries by donating money earned from Cannabis Culture magazine and Emeryseeds.com.

In 1997, the Connecticut Law Revision Commission recommended Connecticut reduce cannabis possession of one ounce or less for adults age 21 and over to a civil fine. In 2001, the New Mexico state-commissioned Drug Policy Advisory Group stated that decriminalizing cannabis "will result in greater availability of resources to respond to more serious crimes without any increased risks to public safety."[98]

A few places in California have been advocating cannabis decriminalization. On November 3, 2004, Oakland passed Proposition Z, which makes "adult recreational marijuana use, cultivation and sales the lowest [city] law enforcement priority." The proposition states the city of Oakland must advocate to the state of California to adopt laws to regulate and tax cannabis. On November 7, 2006, Santa Cruz passed Measure K, which made cannabis the lowest priority for city law enforcement. The measure requests the Santa Cruz City Clerk send letters annually to state and federal representatives advocating reform of cannabis laws. On June 5, 2007, Mendocino County Board of Supervisors voted 4–1 to send a letter in support of the legalization, regulation, and taxation of cannabis to state and federal legislators, and the President of United States.

Ron Paul, a former Texas Congressman and 2008 Presidential Candidate, stated at a rally in response to a question by a medical cannabis patient that he would "never use the federal government to force the law against anybody using marijuana." In his book, The Revolution: A Manifesto he writes, "Regardless of where one stands on the broader drug war, we should all be able to agree on the subject of medical marijuana. Here, the use of an otherwise prohibited substance has been found to relieve unbearable suffering in countless patients. How can we fail to support liberty and individual responsibility in such a clear cut case? What harm does it do to anyone else to allow fellow human beings in pain to find the relief they need?" He is also the cosponsor of the Personal Use of Marijuana by Responsible Adults Act of 2008.

Mike Gravel, a former U.S. senator from Alaska and 2008 presidential candidate, responded to a caller on a C-SPAN program asking about cannabis and the drug war, he stated "That one is real simple, I would legalize marijuana. You should be able to buy that at a liquor store."

Dennis Kucinich, a U.S. representative from Ohio and 2008 presidential candidate, has been an advocate of cannabis legalization. During Kucinich's 2004 presidential campaign, the following was posted on Kucinich's official campaign web site.

Most marijuana users do so responsibly, in a safe, recreational context. These people lead normal, productive lives — pursuing careers, raising families and participating in civic life ... A Kucinich administration would reject the current paradigm of 'all use is abuse' in favor of a drug policy that sets reasonable boundaries for marijuana use by establishing guidelines similar to those already in place for alcohol.

Some members of religious organizations, even while not necessarily being in favor of marijuana consumption, have also spoken in favor of reform, due to medical reasons, or the social costs of enforcement and incarceration. For instance, Revered Samuel Rodriguez of National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conferences stated that "laws that prohibit marijuana affect the minorities significantly and hence should be reconsidered." Religious groups uphold that marijuana does not harm as much as alcohol does and thus legalizing it for medicinal usage would not be harmful to the economy.

In 1974 Dr Robert DuPont began to publicly support decriminalization of cannabis, seeing cannabis as a health problem. But when DuPont left government he changed his mind and declared that "decriminalization is a bad idea". Robert DuPont is still an active opponent of decriminalization of cannabis.