Historically, philosophy encompassed all bodies of knowledge and a practitioner was known as a philosopher. From the time of Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle to the 19th century, "natural philosophy" encompassed astronomy, medicine, and physics. For example, Newton's 1687 Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy later became classified as a book of physics.

In the 19th century, the growth of modern research universities led academic philosophy and other disciplines to professionalize and specialize. Since then, various areas of investigation that were traditionally part of philosophy have become separate academic disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, linguistics, and economics.

Today, major subfields of academic philosophy include metaphysics, which is concerned with the fundamental nature of existence and reality; epistemology, which studies the nature of knowledge and belief; ethics, which is concerned with moral value; and logic, which studies the rules of inference that allow one to derive conclusions from true premises. Other notable subfields include philosophy of science, political philosophy, aesthetics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of mind.

Origins and evolution

Initially the term referred to any body of knowledge. In this sense, philosophy is closely related to religion, mathematics, natural science, education, and politics. Though it has since been classified as a book of physics, Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687) uses the term natural philosophy as it was understood at the time, encompassing disciplines such as astronomy, medicine and physics that later became associated with the sciences.

In section thirteen of his Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, the oldest surviving history of philosophy (3rd century), Diogenes Laërtius presents a three-part division of ancient Greek philosophical inquiry:

- Natural philosophy (i.e. physics, from Greek: ta physika, lit. 'things having to do with physis [nature]') was the study of the constitution and processes of transformation in the physical world.

- Moral philosophy (i.e. ethics, from êthika, 'having to do with character, disposition, manners') was the study of goodness, right and wrong, justice and virtue.

- Metaphysical philosophy (i.e. logic, from logikós, 'of or pertaining to reason or speech') was the study of existence, causation, God, logic, forms, and other abstract objects. (meta ta physika, 'after the Physics')

In Against the Logicians the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus detailed the variety of ways in which the ancient Greek philosophers had divided philosophy, noting that this three-part division was agreed to by Plato, Aristotle, Xenocrates, and the Stoics. The Academic Skeptic philosopher Cicero also followed this three-part division.

This division is not obsolete, but has changed: natural philosophy has split into the various natural sciences, especially physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, and cosmology; moral philosophy has birthed the social sciences, while still including value theory (e.g. ethics, aesthetics, political philosophy, etc.); and metaphysical philosophy has given way to formal sciences such as logic, mathematics and philosophy of science, while still including epistemology, cosmology, etc.

Philosophical progress

Many philosophical debates that began in ancient times are still debated today. McGinn claims that no philosophical progress has occurred during that interval. Chalmers, by contrast, sees progress in philosophy similar to that in science, while Brewer argues that "progress" is the wrong standard by which to judge philosophical activity.

Historical overview

In one general sense, philosophy is associated with wisdom, intellectual culture, and a search for knowledge. In this sense, all cultures and literate societies ask philosophical questions, such as "how are we to live" and "what is the nature of reality." A broad and impartial conception of philosophy, then, finds a reasoned inquiry into such matters as reality, morality, and life in all world civilizations.

Western philosophy

Western philosophy is the philosophical tradition of the Western world, dating back to pre-Socratic thinkers who were active in 6th-century Greece (BCE), such as Thales (c. 624 – c. 545 BCE) and Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE) who practiced a 'love of wisdom' (Latin: philosophia) and were also termed 'students of nature' (physiologoi).

Western philosophy can be divided into three eras:

- Ancient (Greco-Roman).

- Medieval philosophy (referring to Christian European thought).

- Modern philosophy (beginning in the 17th century).

Ancient era

While our knowledge of the ancient era begins with Thales in the 6th century BCE, little is known about the philosophers who came before Socrates (commonly known as the pre-Socratics). The ancient era was dominated by Greek philosophical schools. Most notable among the schools influenced by Socrates' teachings were Plato, who founded the Platonic Academy, and his student Aristotle, who founded the Peripatetic school. Other ancient philosophical traditions influenced by Socrates included Cynicism, Cyrenaicism, Stoicism, and Academic Skepticism. Two other traditions were influenced by Socrates' contemporary, Democritus: Pyrrhonism and Epicureanism. Important topics covered by the Greeks included metaphysics (with competing theories such as atomism and monism), cosmology, the nature of the well-lived life (eudaimonia), the possibility of knowledge, and the nature of reason (logos). With the rise of the Roman empire, Greek philosophy was increasingly discussed in Latin by Romans such as Cicero and Seneca.

Medieval era

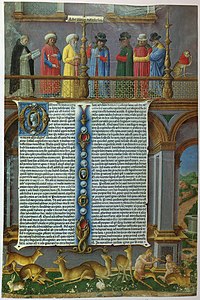

Medieval philosophy (5th–16th centuries) is the period following the fall of the Western Roman Empire and was dominated by the rise of Christianity and hence reflects Judeo-Christian theological concerns as well as retaining a continuity with Greco-Roman thought. Problems such as the existence and nature of God, the nature of faith and reason, metaphysics, the problem of evil were discussed in this period. Some key Medieval thinkers include St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Boethius, Anselm and Roger Bacon. Philosophy for these thinkers was viewed as an aid to Theology (ancilla theologiae) and hence they sought to align their philosophy with their interpretation of sacred scripture. This period saw the development of Scholasticism, a text critical method developed in medieval universities based on close reading and disputation on key texts. The Renaissance period saw increasing focus on classic Greco-Roman thought and on a robust Humanism.

Modern era

Early modern philosophy in the Western world begins with thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes (1596–1650). Following the rise of natural science, modern philosophy was concerned with developing a secular and rational foundation for knowledge and moved away from traditional structures of authority such as religion, scholastic thought and the Church. Major modern philosophers include Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant.

19th-century philosophy (sometimes called late modern philosophy) was influenced by the wider 18th-century movement termed "the Enlightenment", and includes figures such as Hegel a key figure in German idealism, Kierkegaard who developed the foundations for existentialism, Nietzsche a famed anti-Christian, John Stuart Mill who promoted utilitarianism, Karl Marx who developed the foundations for communism and the American William James. The 20th century saw the split between analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, as well as philosophical trends such as phenomenology, existentialism, logical positivism, pragmatism and the linguistic turn.

Middle Eastern philosophy

Pre-Islamic philosophy

The regions of the Fertile Crescent, Iran and Arabia are home to the earliest known philosophical wisdom literature and is today mostly dominated by Islamic culture.

Early Wisdom Literature from the Fertile Crescent was a genre which sought to instruct people on ethical action, practical living and virtue through stories and proverbs. In Ancient Egypt, these texts were known as sebayt ('teachings') and they are central to our understandings of Ancient Egyptian philosophy. Babylonian astronomy also included much philosophical speculations about cosmology which may have influenced the Ancient Greeks.

Jewish philosophy and Christian philosophy are religio-philosophical traditions that developed both in the Middle East and in Europe, which both share certain early Judaic texts (mainly the Tanakh) and monotheistic beliefs. Jewish thinkers such as the Geonim of the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia and Maimonides engaged with Greek and Islamic philosophy. Later Jewish philosophy came under strong Western intellectual influences and includes the works of Moses Mendelssohn who ushered in the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment), Jewish existentialism, and Reform Judaism.

The various traditions of Gnosticism, which were influenced by both Greek and Abrahamic currents, originated around the first century and emphasized spiritual knowledge (gnosis).

Pre-Islamic Iranian philosophy begins with the work of Zoroaster, one of the first promoters of monotheism and of the dualism between good and evil. This dualistic cosmogony influenced later Iranian developments such as Manichaeism, Mazdakism, and Zurvanism.

Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is the philosophical work originating in the Islamic tradition and is mostly done in Arabic. It draws from the religion of Islam as well as from Greco-Roman philosophy. After the Muslim conquests, the translation movement (mid-eighth to the late tenth century) resulted in the works of Greek philosophy becoming available in Arabic.

Early Islamic philosophy developed the Greek philosophical traditions in new innovative directions. This intellectual work inaugurated what is known as the Islamic Golden Age. The two main currents of early Islamic thought are Kalam, which focuses on Islamic theology, and Falsafa, which was based on Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism. The work of Aristotle was very influential among philosophers such as Al-Kindi (9th century), Avicenna (980 – June 1037) and Averroes (12th century). Others such as Al-Ghazali were highly critical of the methods of the Islamic Aristotelians and saw their metaphysical ideas as heretical. Islamic thinkers like Ibn al-Haytham and Al-Biruni also developed a scientific method, experimental medicine, a theory of optics and a legal philosophy. Ibn Khaldun was an influential thinker in philosophy of history.

Islamic thought also deeply influenced European intellectual developments, especially through the commentaries of Averroes on Aristotle. The Mongol invasions and the destruction of Baghdad in 1258 is often seen as marking the end of the Golden Age. Several schools of Islamic philosophy continued to flourish after the Golden Age however, and include currents such as Illuminationist philosophy, Sufi philosophy, and Transcendent theosophy.

The 19th- and 20th-century Arab world saw the Nahda movement (literally meaning 'The Awakening'; also known as the 'Arab Renaissance'), which had a considerable influence on contemporary Islamic philosophy.

Eastern philosophy

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy (Sanskrit: darśana, lit. 'point of view', 'perspective') refers to the diverse philosophical traditions that emerged since the ancient times on the Indian subcontinent. Indian philosophical traditions share various key concepts and ideas, which are defined in different ways and accepted or rejected by the different traditions. These include concepts such as dhárma, karma, pramāṇa, duḥkha, saṃsāra and mokṣa.

Some of the earliest surviving Indian philosophical texts are the Upanishads of the later Vedic period (1000–500 BCE), which are considered to preserve the ideas of Brahmanism. Indian philosophy is commonly grouped based on their relationship to the Vedas and the ideas contained in them. Jainism and Buddhism originated at the end of the Vedic period, while the various traditions grouped under Hinduism mostly emerged after the Vedic period as independent traditions. Hindus generally classify Indian philosophical traditions as either orthodox (āstika) or heterodox (nāstika) depending on whether they accept the authority of the Vedas and the theories of brahman and ātman found therein.

The schools which align themselves with the thought of the Upanishads, the so-called "orthodox" or "Hindu" traditions, are often classified into six darśanas or philosophies:Sānkhya, Yoga, Nyāya, Vaisheshika, Mimāmsā and Vedānta.

The doctrines of the Vedas and Upanishads were interpreted differently by these six schools of Hindu philosophy, with varying degrees of overlap. They represent a "collection of philosophical views that share a textual connection," according to Chadha (2015). They also reflect a tolerance for a diversity of philosophical interpretations within Hinduism while sharing the same foundation.[ii]

Hindu philosophers of the six orthodox schools developed systems of epistemology (pramana) and investigated topics such as metaphysics, ethics, psychology (guṇa), hermeneutics, and soteriology within the framework of the Vedic knowledge, while presenting a diverse collection of interpretations. The commonly named six orthodox schools were the competing philosophical traditions of what has been called the "Hindu synthesis" of classical Hinduism.

There are also other schools of thought which are often seen as "Hindu", though not necessarily orthodox (since they may accept different scriptures as normative, such as the Shaiva Agamas and Tantras), these include different schools of Shavism such as Pashupata, Shaiva Siddhanta, non-dual tantric Shavism (i.e. Trika, Kaula, etc.).

The "Hindu" and "Orthodox" traditions are often contrasted with the "unorthodox" traditions (nāstika, literally "those who reject"), though this is a label that is not used by the "unorthodox" schools themselves. These traditions reject the Vedas as authoritative and often reject major concepts and ideas that are widely accepted by the orthodox schools (such as Ātman, Brahman, and Īśvara). These unorthodox schools include Jainism (accepts ātman but rejects Īśvara, Vedas and Brahman), Buddhism (rejects all orthodox concepts except rebirth and karma), Cārvāka (materialists who reject even rebirth and karma) and Ājīvika (known for their doctrine of fate).

Jain philosophy is one of the only two surviving "unorthodox" traditions (along with Buddhism). It generally accepts the concept of a permanent soul (jiva) as one of the five astikayas (eternal, infinite categories that make up the substance of existence). The other four being dhárma, adharma, ākāśa ('space'), and pudgala ('matter'). Jain thought holds that all existence is cyclic, eternal and uncreated.

Some of the most important elements of Jain philosophy are the Jain theory of karma, the doctrine of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and the theory of "many-sidedness" or Anēkāntavāda. The Tattvartha Sutra is the earliest known, most comprehensive and authoritative compilation of Jain philosophy.

Buddhist philosophy

Buddhist philosophy begins with the thought of Gautama Buddha (fl. between 6th and 4th century BCE) and is preserved in the early Buddhist texts. It originated in the Indian region of Magadha and later spread to the rest of the Indian subcontinent, East Asia, Tibet, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. In these regions, Buddhist thought developed into different philosophical traditions which used various languages (like Tibetan, Chinese and Pali). As such, Buddhist philosophy is a trans-cultural and international phenomenon.

The dominant Buddhist philosophical traditions in East Asian nations are mainly based on Indian Mahayana Buddhism. The philosophy of the Theravada school is dominant in Southeast Asian countries like Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand.

Because ignorance to the true nature of things is considered one of the roots of suffering (dukkha), Buddhist philosophy is concerned with epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and psychology. Buddhist philosophical texts must also be understood within the context of meditative practices which are supposed to bring about certain cognitive shifts. Key innovative concepts include the four noble truths as an analysis of dukkha, anicca (impermanence), and anatta (non-self).

After the death of the Buddha, various groups began to systematize his main teachings, eventually developing comprehensive philosophical systems termed Abhidharma. Following the Abhidharma schools, Indian Mahayana philosophers such as Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu developed the theories of śūnyatā ('emptiness of all phenomena') and vijñapti-matra ('appearance only'), a form of phenomenology or transcendental idealism. The Dignāga school of pramāṇa ('means of knowledge') promoted a sophisticated form of Buddhist epistemology.

There were numerous schools, sub-schools, and traditions of Buddhist philosophy in ancient and medieval India. According to Oxford professor of Buddhist philosophy Jan Westerhoff, the major Indian schools from 300 BCE to 1000 CE were: the Mahāsāṃghika tradition (now extinct), the Sthavira schools (such as Sarvāstivāda, Vibhajyavāda and Pudgalavāda) and the Mahayana schools. Many of these traditions were also studied in other regions, like Central Asia and China, having been brought there by Buddhist missionaries.

After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the Tibetan Buddhist, East Asian Buddhist and Theravada Buddhist traditions.

East Asian philosophy

East Asian philosophical thought began in Ancient China, and Chinese philosophy begins during the Western Zhou Dynasty and the following periods after its fall when the "Hundred Schools of Thought" flourished (6th century to 221 BCE). This period was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments and saw the rise of the major philosophical schools of China such as Confucianism (also known as Ruism), Legalism, and Taoism as well as numerous other less influential schools like Mohism and Naturalism. These philosophical traditions developed metaphysical, political and ethical theories such Tao, Yin and yang, Ren and Li. These schools of thought further developed during the Han (206 BCE – 220 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) eras, forming new philosophical movements like Xuanxue (also called Neo-Taoism), and Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism was a syncretic philosophy, which incorporated the ideas of different Chinese philosophical traditions, including Buddhism and Taoism. Neo-Confucianism came to dominate the education system during the Song dynasty (960–1297), and its ideas served as the philosophical basis of the imperial exams for the scholar official class. Some of the most important Neo-Confucian thinkers are the Tang scholars Han Yu and Li Ao as well as the Song thinkers Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200). Zhu Xi compiled the Confucian canon, which consists of the Four Books (the Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius). The Ming scholar Wang Yangming (1472–1529) is a later but important philosopher of this tradition as well.

Buddhism began arriving in China during the Han Dynasty, through a gradual Silk road transmission and through native influences developed distinct Chinese forms (such as Chan/Zen) which spread throughout the East Asian cultural sphere.

Chinese culture was highly influential on the traditions of other East Asian states and its philosophy directly influenced Korean philosophy, Vietnamese philosophy and Japanese philosophy. During later Chinese dynasties like the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) as well as in the Korean Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) a resurgent Neo-Confucianism led by thinkers such as Wang Yangming (1472–1529) became the dominant school of thought, and was promoted by the imperial state. In Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867) was also strongly influenced by Confucian philosophy. Confucianism continues to influence the ideas and worldview of the nations of the Chinese cultural sphere today.

In the Modern era, Chinese thinkers incorporated ideas from Western philosophy. Chinese Marxist philosophy developed under the influence of Mao Zedong, while a Chinese pragmatism developed under Hu Shih. The old traditional philosophies also began to reassert themselves in the 20th century. For example, New Confucianism, led by figures such as Xiong Shili, has become quite influential. Likewise, Humanistic Buddhism is a recent modernist Buddhist movement.

Modern Japanese thought meanwhile developed under strong Western influences such as the study of Western Sciences (Rangaku) and the modernist Meirokusha intellectual society which drew from European enlightenment thought and promoted liberal reforms as well as Western philosophies like Liberalism and Utilitarianism. Another trend in modern Japanese philosophy was the "National Studies" (Kokugaku) tradition. This intellectual trend sought to study and promote ancient Japanese thought and culture. Kokugaku thinkers such as Motoori Norinaga sought to return to a pure Japanese tradition which they called Shinto that they saw as untainted by foreign elements.

During the 20th century, the Kyoto School, an influential and unique Japanese philosophical school developed from Western phenomenology and Medieval Japanese Buddhist philosophy such as that of Dogen.

African philosophy

African philosophy is philosophy produced by African people, philosophy that presents African worldviews, ideas and themes, or philosophy that uses distinct African philosophical methods. Modern African thought has been occupied with Ethnophilosophy, with defining the very meaning of African philosophy and its unique characteristics and what it means to be African.

During the 17th century, Ethiopian philosophy developed a robust literary tradition as exemplified by Zera Yacob. Another early African philosopher was Anton Wilhelm Amo (c. 1703–1759) who became a respected philosopher in Germany. Distinct African philosophical ideas include Ujamaa, the Bantu idea of 'Force', Négritude, Pan-Africanism and Ubuntu. Contemporary African thought has also seen the development of Professional philosophy and of Africana philosophy, the philosophical literature of the African diaspora which includes currents such as black existentialism by African-Americans. Some modern African thinkers have been influenced by Marxism, African-American literature, Critical theory, Critical race theory, Postcolonialism and Feminism.

Indigenous American philosophy

Indigenous-American philosophical thought consists of a wide variety of beliefs and traditions among different American cultures. Among some of U.S. Native American communities, there is a belief in a metaphysical principle called the 'Great Spirit' (Siouan: wakȟáŋ tȟáŋka; Algonquian: gitche manitou). Another widely shared concept was that of orenda ('spiritual power'). According to Whiteley (1998), for the Native Americans, "mind is critically informed by transcendental experience (dreams, visions and so on) as well as by reason." The practices to access these transcendental experiences are termed shamanism. Another feature of the indigenous American worldviews was their extension of ethics to non-human animals and plants.

In Mesoamerica, Aztec philosophy was an intellectual tradition developed by individuals called Tlamatini ('those who know something') and its ideas are preserved in various Aztec codices. The Aztec worldview posited the concept of an ultimate universal energy or force called Ōmeteōtl ('Dual Cosmic Energy') which sought a way to live in balance with a constantly changing, "slippery" world.

The theory of Teotl can be seen as a form of Pantheism. Aztec philosophers developed theories of metaphysics, epistemology, values, and aesthetics. Aztec ethics was focused on seeking tlamatiliztli ('knowledge', 'wisdom') which was based on moderation and balance in all actions as in the Nahua proverb "the middle good is necessary."

The Inca civilization also had an elite class of philosopher-scholars termed the Amawtakuna who were important in the Inca education system as teachers of religion, tradition, history and ethics. Key concepts of Andean thought are Yanantin and Masintin which involve a theory of “complementary opposites” that sees polarities (such as male/female, dark/light) as interdependent parts of a harmonious whole.

Women in philosophy

Although men have generally dominated philosophical discourse, women philosophers have engaged in the discipline throughout history. Ancient examples include Hipparchia of Maroneia (active c. 325 BCE) and Arete of Cyrene (active 5th–4th centuries BCE). Some women philosophers were accepted during the medieval and modern eras, but none became part of the Western canon until the 20th and 21st century, when many suggest that G.E.M. Anscombe, Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, and Susanne Langer entered the canon.

In the early 1800s, some colleges and universities in the UK and US began admitting women, producing more female academics. Nevertheless, U.S. Department of Education reports from the 1990s indicate that few women ended up in philosophy, and that philosophy is one of the least gender-proportionate fields in the humanities, with women making up somewhere between 17% and 30% of philosophy faculty according to some studies.

Branches of philosophy

Philosophical questions can be grouped into various branches. These groupings allow philosophers to focus on a set of similar topics and interact with other thinkers who are interested in the same questions.

These divisions are neither exhaustive, nor mutually exclusive. (A philosopher might specialize in Kantian epistemology, or Platonic aesthetics, or modern political philosophy). Furthermore, these philosophical inquiries sometimes overlap with each other and with other inquiries such as science, religion or mathematics.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the "critical reflection on art, culture and nature." It addresses the nature of art, beauty and taste, enjoyment, emotional values, perception and with the creation and appreciation of beauty. It is more precisely defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste. Its major divisions are art theory, literary theory, film theory and music theory. An example from art theory is to discern the set of principles underlying the work of a particular artist or artistic movement such as the Cubist aesthetic.

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, studies what constitutes good and bad conduct, right and wrong values, and good and evil. Its primary investigations include how to live a good life and identifying standards of morality. It also includes investigating whether or not there is a best way to live or a universal moral standard, and if so, how we come to learn about it. The main branches of ethics are normative ethics, meta-ethics and applied ethics.

The three main views in ethics about what constitute moral actions are:

- Consequentialism, which judges actions based on their consequences. One such view is utilitarianism, which judges actions based on the net happiness (or pleasure) and/or lack of suffering (or pain) that they produce.

- Deontology, which judges actions based on whether or not they are in accordance with one's moral duty. In the standard form defended by Immanuel Kant, deontology is concerned with whether or not a choice respects the moral agency of other people, regardless of its consequences.

- Virtue ethics, which judges actions based on the moral character of the agent who performs them and whether they conform to what an ideally virtuous agent would do.

Epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies knowledge. Epistemologists examine putative sources of knowledge, including perceptual experience, reason, memory, and testimony. They also investigate questions about the nature of truth, belief, justification, and rationality.

Philosophical skepticism, which raises doubts about some or all claims to knowledge, has been a topic of interest throughout the history of philosophy. It arose early in Pre-Socratic philosophy and became formalized with Pyrrho, the founder of the earliest Western school of philosophical skepticism. It features prominently in the works of modern philosophers René Descartes and David Hume, and has remained a central topic in contemporary epistemological debates.

One of the most notable epistemological debates is between empiricism and rationalism. Empiricism places emphasis on observational evidence via sensory experience as the source of knowledge. Empiricism is associated with a posteriori knowledge, which is obtained through experience (such as scientific knowledge). Rationalism places emphasis on reason as a source of knowledge. Rationalism is associated with a priori knowledge, which is independent of experience (such as logic and mathematics).

One central debate in contemporary epistemology is about the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, which might include truth and justification. This debate was largely the result of attempts to solve the Gettier problem. Another common subject of contemporary debates is the regress problem, which occurs when trying to offer proof or justification for any belief, statement, or proposition. The problem is that whatever the source of justification may be, that source must either be without justification (in which case it must be treated as an arbitrary foundation for belief), or it must have some further justification (in which case justification must either be the result of circular reasoning, as in coherentism, or the result of an infinite regress, as in infinitism).

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, such as existence, time, objects and their properties, wholes and their parts, events, processes and causation and the relationship between mind and body. Metaphysics includes cosmology, the study of the world in its entirety and ontology, the study of being.

A major point of debate is between realism, which holds that there are entities that exist independently of their mental perception and idealism, which holds that reality is mentally constructed or otherwise immaterial. Metaphysics deals with the topic of identity. Essence is the set of attributes that make an object what it fundamentally is and without which it loses its identity while accident is a property that the object has, without which the object can still retain its identity. Particulars are objects that are said to exist in space and time, as opposed to abstract objects, such as numbers, and universals, which are properties held by multiple particulars, such as redness or a gender. The type of existence, if any, of universals and abstract objects is an issue of debate.

Logic

Logic is the study of reasoning and argument.

Deductive reasoning is when, given certain premises, conclusions are unavoidably implied. Rules of inference are used to infer conclusions such as, modus ponens, where given “A” and “If A then B”, then “B” must be concluded.

Because sound reasoning is an essential element of all sciences, social sciences and humanities disciplines, logic became a formal science. Sub-fields include mathematical logic, philosophical logic, Modal logic, computational logic and non-classical logics. A major question in the philosophy of mathematics is whether mathematical entities are objective and discovered, called mathematical realism, or invented, called mathematical antirealism.

Other subfields

Mind and language

Philosophy of language explores the nature, origins, and use of language. Philosophy of mind explores the nature of the mind and its relationship to the body, as typified by disputes between materialism and dualism. In recent years, this branch has become related to cognitive science.

Philosophy of science

The philosophy of science explores the foundations, methods, history, implications and purpose of science. Many of its subdivisions correspond to specific branches of science. For example, philosophy of biology deals specifically with the metaphysical, epistemological and ethical issues in the biomedical and life sciences.

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of government and the relationship of individuals (or families and clans) to communities including the state. It includes questions about justice, law, property and the rights and obligations of the citizen. Political philosophy, ethics, and aesthetics are traditionally linked subjects, under the general heading of value theory as they involve a normative or evaluative aspect.

Philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion deals with questions that involve religion and religious ideas from a philosophically neutral perspective (as opposed to theology which begins from religious convictions). Traditionally, religious questions were not seen as a separate field from philosophy proper, the idea of a separate field only arose in the 19th century.

Issues include the existence of God, the relationship between reason and faith, questions of religious epistemology, the relationship between religion and science, how to interpret religious experiences, questions about the possibility of an afterlife, the problem of religious language and the existence of souls and responses to religious pluralism and diversity.

Metaphilosophy

Metaphilosophy explores the aims of philosophy, its boundaries and its methods.

Applied and professional philosophy

Some of those who study philosophy become professional philosophers, typically by working as professors who teach, research and write in academic institutions. However, most students of academic philosophy later contribute to law, journalism, religion, sciences, politics, business, or various arts. For example, public figures who have degrees in philosophy include comedians Steve Martin and Ricky Gervais, filmmaker Terrence Malick, Pope John Paul II, Wikipedia co-founder Larry Sanger, technology entrepreneur Peter Thiel, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Bryer and US vice presidential candidate Carly Fiorina. Curtis White has argued that philosophical tools are essential to humanities, sciences and social sciences.

Recent efforts to avail the general public to the work and relevance of philosophers include the million-dollar Berggruen Prize, first awarded to Charles Taylor in 2016. Some philosophers argue that this professionalization has negatively affected the discipline.