Economic globalization is one of the three main dimensions of globalization commonly found in academic literature, with the two others being political globalization and cultural globalization, as well as the general term of globalization. Economic globalization refers to the widespread international movement of goods, capital, services, technology and information. It is the increasing economic integration and interdependence of national, regional, and local economies across the world through an intensification of cross-border movement of goods, services, technologies and capital. Economic globalization primarily comprises the globalization of production, finance, markets, technology, organizational regimes, institutions, corporations, and people.

While economic globalization has been expanding since the emergence of trans-national trade, it has grown at an increased rate due to improvements in the efficiency of long-distance transportation, advances in telecommunication, the importance of information rather than physical capital in the modern economy, and by developments in science and technology. The rate of globalization has also increased under the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, in which countries gradually cut down trade barriers and opened up their current accounts and capital accounts. This recent boom has been largely supported by developed economies integrating with developing countries through foreign direct investment, lowering costs of doing business, the reduction of trade barriers, and in many cases cross-border migration.

Evolution of globalization

History

International commodity markets, labor markets, and capital markets make up the economy and define economic globalization.

Beginning as early as 6500 BCE, people in Syria were trading livestock, tools, and other items. In Sumer, an early civilization in Mesopotamia, a token system was one of the first forms of commodity money. Labor markets consist of workers, employers, wages, income, supply and demand. Labor markets have been around as long as commodity markets. The first labor markets provided workers to grow crops and tend livestock for later sale in local markets. Capital markets emerged in industries that require resources beyond those of an individual farmer.

Technology

Globalization is about interconnecting people around the world beyond the physical barrier of geographical boundaries.

These advances in economic globalization were disrupted by World War I. Most of the global economic powers constructed protectionist economic policies and introduced trade barriers that slowed trade growth to the point of stagnation. This caused a slowing of worldwide trade and even led to other countries introducing immigration caps. Globalization did not fully resume until the 1970s, when governments began to emphasize the benefits of trade. Today, follow-on advances in technology have led to the rapid expansion of global trade.

Three suggested factors accelerated economic globalization: advancement of science and technology, market oriented economic reforms, and contributions by multinational corporations.

The 1956 invention of containerized shipping, along with increases in ship sizes, were a major part of the reduction in shipping costs.

Policy and government

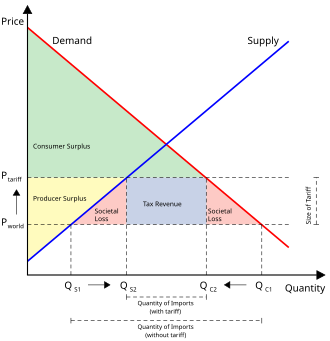

The GATT/WTO framework, which was initiated in 1947, led participating countries to reduce their tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. Indeed, the idea of Most Favoured Nation was essential to the GATT. In order to accede, governments had to shift their economies from central planning to market driven, especially after the fall of the Soviet Union.

On 27 October 1986, the London Stock Exchange enacted newly deregulated rules that enabled global interconnection of markets, with an expectation of huge increases in market activity. This event came to be known as the Big Bang.

By the time the World Trade Organization was established in 1994 as the baton was passed from the GATT, it had grown to 128 countries, including Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia. The year 1995 saw the WTO pass the General Agreement on Trade in Services, while the 1998 defeat of the OECD's Multilateral Agreement on Investment was a hiccup on the route to economic globalization.

Multinational corporations reorganized production to take advantage of these opportunities. Labor-intensive production migrated to areas with lower labor costs, especially China, later followed by other functions as skill levels increased. Networks raised the level of wealth consumption and geographical mobility. This highly dynamic worldwide system had powerful ramifications. The World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference of 1999 and associated 1999 Seattle WTO protests were a significant step on the road to economic globalization.

The People's Republic of China (2001) and the last remnants of ex-Soviet bloc countries like Ukraine (2008) and Russia (2012) were admitted much later to the WTO process after painful structural reforms.

The Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, which entered into force on 1 July 2018, is an effort to harmonize tax regimes in order to prevent multi-national firms from taking advantage of loopholes like Ireland's Green Jersey BEPS tool.

Global actors

International governmental organizations

An intergovernmental organization or international governmental organization (IGO) refers to an entity created by treaty, involving two or more nations, to work in good faith, on issues of common interest. IGO's strive for peace, security and deal with economic and social questions. Examples include: The United Nations, The World Bank and on a regional level The North Atlantic Treaty Organization among others.

International non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

International non-governmental organizations include charities, non-profit advocacy groups, business associations, and cultural associations. International charitable activities increased after World War II and on the whole NGOs provide more economic aid to developing countries than developed country governments.

Businesses

Since the 1970s, multinational businesses have increasingly relied on outsourcing and subcontracting across vast geographical spaces, as supply chains are global and intermediate products are produced. Firms also engage in inter-firm alliances and rely on foreign research and development. This in contrast to past periods where firms kept production internalized or within a localized geography. Innovations in communications and transportation technology, as well as greater economic openness and less government intervention have made a shift away from internalization more feasible. Additionally, businesses going global learn the tools to effectively interact in a culturally agile way with people of many diverse cultural backgrounds.

Migrants

International migrants transfer significant amounts of money through remittances to lower-income relatives. Communities of migrants in the destination country often provide new arrivals with information and ideas about how to earn money. In some cases, this has resulted in disproportionately high representation of some ethnic groups in certain industries, especially if economy success encourages more people to move from the source country. Movement of people also spreads technology and aspects of business culture, and moves accumulated financial assets.

Impact

Economic growth and poverty reduction

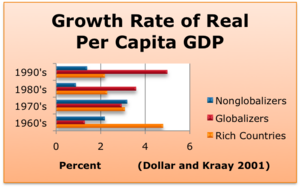

Economic growth accelerated and poverty declined globally following the acceleration of globalization.

Per capita GDP growth in the post-1980 globalizers accelerated from 1.4 percent a year in the 1960s and 2.9 percent a year in the 1970s to 3.5 percent in the 1980s and 5.0 percent in the 1990s. This acceleration in growth is even more remarkable given that the rich countries saw steady declines in growth from a high of 4.7 percent in the 1960s to 2.2 percent in the 1990s. Also, the non-globalizing developing countries did much worse than the globalizers, with the former's annual growth rates falling from highs of 3.3 percent during the 1970s to only 1.4 percent during the 1990s. This rapid growth among the globalizers is not simply due to the strong performances of China and India in the 1980s and 1990s—18 out of the 24 globalizers experienced increases in growth, many of them quite substantial."

According to the International Monetary Fund, growth benefits of economic globalization are widely shared. While several globalizers have seen an increase in inequality, most notably China, this increase in inequality is a result of domestic liberalization, restrictions on internal migration, and agricultural policies, rather than a result of international trade.

Poverty has been reduced as evidenced by a 5.4 percent annual growth in income for the poorest fifth of the population of Malaysia. Even in China, where inequality continues to be a problem, the poorest fifth of the population saw a 3.8 percent annual growth in income. In several countries, those living below the dollar-per-day poverty threshold declined. In China, the rate declined from 20 to 15 percent and in Bangladesh the rate dropped from 43 to 36 percent.

Globalizers are narrowing the per capita income gap between the rich and the globalizing nations. China, India, and Bangladesh, some of the newly industrialised nations in the world, have greatly narrowed inequality due to their economic expansion.

Global supply chain

The global supply chain consists of complex interconnected networks that allow companies to produce handle and distribute various goods and services to the public worldwide.

Corporations manage their supply chain to take advantage of cheaper costs of production. A supply chain is a system of organizations, people, activities, information, and resources involved in moving a product or service from supplier to customer. Supply chain activities involve the transformation of natural resources, raw materials, and components into a finished product that is delivered to the end customer. Supply chains link value chains. Supply and demand can be very fickle, depending on factors such as the weather, consumer demand, and large orders placed by multinational corporations.

Labor conditions and environment

"Race to the bottom"

Globalization is sometimes perceived as a cause of a phenomenon called the "race to the bottom" that implies that to minimize cost and increase delivery speed, businesses tend to locate operations in countries with the least stringent environmental and labor regulations. Pressure to do this is increased if competitors lower costs by the same means. This both directly results poor working conditions, low wages, job insecurity, and pollution, but also encourages governments to under-regulate in order to attract jobs and economic investment. However, if business demand is sufficiently high, the labor pool in low-wage countries becomes exhausted (as has happened in the PRC), resulting in higher wages due to competition, and more demand from the public for government protection against exploitation and pollution. From 2003 to 2013, wages in China and India have gone up by around 10–20% a year.

Health risks

In developing countries with loose labor regulations, there are adverse health consequences from working long hours and individuals that burden themselves from working within vasts global supply chains. Women in agriculture, for example, are often asked to work long hours handling chemicals such as pesticides and fertilizers without any protection.

Although both men and women experience shortcomings with health, the final reports stated that women, with the double burden of domestic and paid work experience an increased the risk of psychological distress and suboptimal health. Strazdins concluded that negative work-family spillover especially is associated with health problems among both women and men, and negative family-work spillover is related to a poorer health status among women."

It is common for the work lifestyle to bring forth adverse health conditions or even death due to weak safety measure policies. After the tragic collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh where over 800 deaths occurred the country has since then made efforts in boosting up their safety policies to better accommodate workers.

Mistreatment

In developing countries with loose labor regulations and a large supply of low-skill, low-cost workers, there are risks for mistreatment of some workers, especially women and children. Poor working conditions and sexual harassment are just some of the mistreatment faced by women in the textile supply chain. Marina Prieto-Carrón shows in her research in Central America that women in sweatshops are not even supplied with toilet paper in the bathroom everyday. The reason it costs corporations more is because people can not work to their full potential in poor conditions, affecting the global marketplace. Furthermore, when corporations decide to change manufacturing rates or locations in industries that employ more women, they are often left with no job nor assistance. This kind of sudden reduction or elimination in hours is seen in industries such as the textile industry and agriculture industry, both of which employ a higher number of women than men. One solution to mistreatment of women in the supply chain is more involvement from the corporation and trying to regulate the outsourcing of their product.

Global labor and fair trade movements

Several movements, such as the fair trade movement and the anti-sweatshop movement, claim to promote a more socially just global economy. The fair trade movement works towards improving trade, development and production for disadvantaged producers. The fair trade movement has reached 1.6 billion US dollars in annual sales. The movement works to raise consumer awareness of exploitation of developing countries. Fair trade works under the motto of "trade, not aid", to improve the quality of life for farmers and merchants by participating in direct sales, providing better prices and supporting the community. Meanwhile, the anti-sweatshop movement is to protest the unfair treatment caused by some companies.

Various transnational organizations advocate for improved labor standards in developing countries. This including labor unions, who are put at a negotiating disadvantage when an employer can relocate or outsource operations to a different country.

Capital flight

Capital flight occurs when assets or money rapidly flow out of a country because of that country's recent increase in unfavorable financial conditions such as taxes, tariffs, labor costs, government debt or capital controls. This is usually accompanied by a sharp drop in the exchange rate of the affected country or a forced devaluation for countries living under fixed exchange rates. Currency declines improve the terms of trade, but reduce the monetary value of financial and other assets in the country. This leads to decreases in the purchasing power of the country's assets.

A 2008 paper published by Global Financial Integrity estimated capital flight to be leaving developing countries at the rate of "$850 billion to $1 trillion a year." But capital flight also affects developed countries. A 2009 article in The Times reported that hundreds of wealthy financiers and entrepreneurs had recently fled the United Kingdom in response to recent tax increases, relocating to low tax destinations such as Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the British Virgin Islands. In May 2012 the scale of Greek capital flight in the wake of the first "undecided" legislative election was estimated at €4 billion a week.

Capital flight can cause liquidity crises in directly affected countries and can cause related difficulties in other countries involved in international commerce such as shipping and finance. Asset holders may be forced into distress sales. Borrowers typically face higher loan costs and collateral requirements, compared to periods of ample liquidity, and unsecured debt is nearly impossible to obtain. Typically, during a liquidity crisis, the interbank lending market stalls.

Inequality

While within-country income inequality has increased throughout the globalization period, globally inequality has lessened as developing countries have experienced much more rapid growth. Economic inequality varies between societies, historical periods, economic structures or economic systems, ongoing or past wars, between genders, and between differences in individuals' abilities to create wealth. Among the various numerical indices for measuring economic inequality, the Gini coefficient is most often-cited.

Economic inequality includes equity, equality of outcome and subsequent equality of opportunity. Although earlier studies considered economic inequality as necessary and beneficial, some economists see it as an important social problem. Early studies suggesting that greater equality inhibits economic growth did not account for lags between inequality changes and growth changes. Later studies claimed that one of the most robust determinants of sustained economic growth is the level of income inequality.

International inequality is inequality between countries. Income differences between rich and poor countries are very large, although they are changing rapidly. Per capita incomes in China and India doubled in the prior twenty years, a feat that required 150 years in the US. According to the United Nations Human Development Report for 2013, for countries at varying levels of the UN Human Development Index the GNP per capita grew between 2004 and 2013 from 24,806 to 33,391 or 35% (very high human development), 4,269 to 5,428 or 27% (medium) and 1,184 to 1,633 or 38% (low) PPP$, respectively (PPP$ = purchasing power parity measured in United States dollars).

Certain demographic changes in the developing world after active economic liberalization and international integration resulted in rising welfare and hence, reduced inequality. According to Martin Wolf, in the developing world as a whole, life expectancy rose by four months each year after 1970 and infant mortality rate declined from 107 per thousand in 1970 to 58 in 2000 due to improvements in standards of living and health conditions. Also, adult literacy in developing countries rose from 53% in 1970 to 74% in 1998 and much lower illiteracy rate among the young guarantees that rates will continue to fall as time passes. Furthermore, the reduction in fertility rates in the developing world as a whole from 4.1 births per woman in 1980 to 2.8 in 2000 indicates improved education level of women on fertility, and control of fewer children with more parental attention and investment. Consequentially, more prosperous and educated parents with fewer children have chosen to withdraw their children from the labor force to give them opportunities to be educated at school improving the issue of child labor. Thus, despite seemingly unequal distribution of income within these developing countries, their economic growth and development have brought about improved standards of living and welfare for the population as a whole.

Economic development spurred by international investment or trade can increase local income inequality as workers with more education and skills can find higher-paying work. This can be mitigated with government funding of education. Another way globalization increases income inequality is by increasing the size of the market available for any particular good or service. This allows the owners of companies that service global markets to reap disproportionately larger profits. This may happen at the expense of local companies that would have otherwise been able to dominate the domestic market, which would have spread profits around to a larger number of owners. On the other hand, globalized stock markets allow more people to invest internationally, and get a share of profits from companies they otherwise could not.

Resource insecurity

A systematic, and possibly first large-scale, cross-sectoral analysis of water, energy and land in security in 189 countries that links national and sector consumption to sources showed that countries and sectors are highly exposed to over-exploited, insecure, and degraded such resources. The 2020 study finds that economic globalization has decreased security of global supply chains with most countries exhibiting greater exposure to resource risks via international trade – mainly from remote production sources – and that diversifying trading partners is unlikely to help nations and sectors to reduce these or to improve their resource self-sufficiency.

Competitive advantages

Businesses in developed countries tend to be more highly automated, have more sophisticated technology and techniques, and have better national infrastructure. For these reasons and sometimes due to economies of scale, they can sometimes out-compete similar businesses in developing countries. This is a substantial issue in international agriculture, where Western farms tend to be large and highly productive due to agricultural machinery, fertilizer, and pesticides; but developing-country farms tend to be smaller and rely heavily on manual labor. Conversely, cheaper manual labor in developing countries allowed workers there to out-compete workers in higher-wage countries for jobs in labor-intensive industries. As the theory of competitive advantage predicts, instead of each country producing all the goods and services it needs domestically, a country's economy tends to specialize in certain areas where it is more productive (though in the long term the differences may be equalized, resulting in a more balanced economy).

Tax havens

A tax haven is a state, country or territory where certain taxes are levied at a low rate or not at all, which are used by businesses for tax avoidance and tax evasion. Individuals and/or corporate entities can find it attractive to move themselves to areas with reduced taxation. This creates a situation of tax competition among governments. Taxes vary substantially across jurisdictions. Sovereign states have theoretically unlimited powers to enact tax laws affecting their territories, unless limited by previous international treaties. The central feature of a tax haven is that its laws and other measures can be used to evade or avoid the tax laws or regulations of other jurisdictions. In its December 2008 report on the use of tax havens by American corporations, the U.S. Government Accountability Office regarded the following characteristics as indicative of a tax haven: nil or nominal taxes; lack of effective exchange of tax information with foreign tax authorities; lack of transparency in the operation of legislative, legal or administrative provisions; no requirement for a substantive local presence; and self-promotion as an offshore financial center.

A 2012 report from the Tax Justice Network estimated that between US$21 trillion and $32 trillion is sheltered from taxes in tax havens worldwide. If such hidden offshore assets are considered, many countries with governments nominally in debt would be net creditor nations. However, the tax policy director of the Chartered Institute of Taxation expressed skepticism over the accuracy of the figures. Daniel J. Mitchell of the US-based Cato Institute says that the report also assumes, when considering notional lost tax revenue, that 100% of the money deposited offshore is evading payment of tax.

The tax shelter benefits result in a tax incidence disadvantaging the poor. Many tax havens are thought to have connections to "fraud, money laundering and terrorism." Accountants' opinions on the propriety of tax havens have been evolving, as have the opinions of their corporate users, governments, and politicians, although their use by Fortune 500 companies and others remains widespread. Reform proposals centering on the Big Four accountancy firms have been advanced. Some governments appear to be using computer spyware to scrutinize corporations' finances.

Cultural effects

Economic globalization may affect culture. Populations may mimic the international flow of capital and labor markets in the form of immigration and the merger of cultures. Foreign resources and economic measures may affect different native cultures and may cause assimilation of a native people. As these populations are exposed to the English language, computers, western music, and North American culture, changes are being noted in shrinking family size, immigration to larger cities, more casual dating practices, and gender roles are transformed.

Yu Xintian noted two contrary trends in culture due to economic globalization. Yu argued that culture and industry not only flow from the developed world to the rest, but trigger an effort to protect local cultures. He notes that economic globalization began after World War II, whereas internationalization began over a century ago.

George Ritzer wrote about the McDonaldization of society and how fast food businesses spread throughout the United States and the rest of the world, attracting other places to adopt fast food culture. Ritzer describes other businesses such as The Body Shop, a British cosmetics company, that have copied McDonald's business model for expansion and influence. In 2006, 233 of 280 or over 80% of new McDonald's opened outside the US. In 2007, Japan had 2,828 McDonald's locations.

Global media companies export information around the world. This creates a mostly one-way flow of information, and exposure to mostly western products and values. Companies like CNN, Reuters and the BBC dominate the global airwaves with western points of view. Other media news companies such as Qatar's Al Jazeera network offer a different point of view, but reach and influence fewer people.

Migration

"With an estimated 210 million people living outside their country of origin (International Labour Organization [ILO] 2010), international migration has touched the lives of almost everyone in both the sending and receiving countries of the Global South and the Global North". Because of advances made in technology, human beings as well as goods are able to move through different countries and regions with relative ease.

See also