Sleep is a naturally recurring state of mind and body, characterized by altered consciousness, relatively inhibited sensory activity, reduced muscle activity and inhibition of nearly all voluntary muscles during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and reduced interactions with surroundings. It is distinguished from wakefulness by a decreased ability to react to stimuli, but more reactive than a coma or disorders of consciousness, with sleep displaying different, active brain patterns.

Sleep occurs in repeating periods, in which the body alternates between two distinct modes: REM sleep and non-REM sleep. Although REM stands for "rapid eye movement", this mode of sleep has many other aspects, including virtual paralysis of the body. A well-known feature of sleep is the dream, an experience typically recounted in narrative form, which resembles waking life while in progress, but which usually can later be distinguished as fantasy. During sleep, most of the body's systems are in an anabolic state, helping to restore the immune, nervous, skeletal, and muscular systems; these are vital processes that maintain mood, memory, and cognitive function, and play a large role in the function of the endocrine and immune systems. The internal circadian clock promotes sleep daily at night. The diverse purposes and mechanisms of sleep are the subject of substantial ongoing research. Sleep is a highly conserved behavior across animal evolution.

Humans may suffer from various sleep disorders, including dyssomnias such as insomnia, hypersomnia, narcolepsy, and sleep apnea; parasomnias such as sleepwalking and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; bruxism; and circadian rhythm sleep disorders. The use of artificial light has substantially altered humanity's sleep patterns.

Physiology

The most pronounced physiological changes in sleep occur in the brain. The brain uses significantly less energy during sleep than it does when awake, especially during non-REM sleep. In areas with reduced activity, the brain restores its supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the molecule used for short-term storage and transport of energy. In quiet waking, the brain is responsible for 20% of the body's energy use, thus this reduction has a noticeable effect on overall energy consumption.

Sleep increases the sensory threshold. In other words, sleeping persons perceive fewer stimuli, but can generally still respond to loud noises and other salient sensory events.

During slow-wave sleep, humans secrete bursts of growth hormone. All sleep, even during the day, is associated with secretion of prolactin.

Key physiological methods for monitoring and measuring changes during sleep include electroencephalography (EEG) of brain waves, electrooculography (EOG) of eye movements, and electromyography (EMG) of skeletal muscle activity. Simultaneous collection of these measurements is called polysomnography, and can be performed in a specialized sleep laboratory. Sleep researchers also use simplified electrocardiography (EKG) for cardiac activity and actigraphy for motor movements.

Non-REM and REM sleep

Sleep is divided into two broad types: non-rapid eye movement (non-REM or NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Non-REM and REM sleep are so different that physiologists identify them as distinct behavioral states. Non-REM sleep occurs first and after a transitional period is called slow-wave sleep or deep sleep. During this phase, body temperature and heart rate fall, and the brain uses less energy. REM sleep, also known as paradoxical sleep, represents a smaller portion of total sleep time. It is the main occasion for dreams (or nightmares), and is associated with desynchronized and fast brain waves, eye movements, loss of muscle tone, and suspension of homeostasis.

The sleep cycle of alternate NREM and REM sleep takes an average of 90 minutes, occurring 4–6 times in a good night's sleep. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) divides NREM into three stages: N1, N2, and N3, the last of which is also called delta sleep or slow-wave sleep. The whole period normally proceeds in the order: N1 → N2 → N3 → N2 → REM. REM sleep occurs as a person returns to stage 2 or 1 from a deep sleep. There is a greater amount of deep sleep (stage N3) earlier in the night, while the proportion of REM sleep increases in the two cycles just before natural awakening.

Awakening

Awakening can mean the end of sleep, or simply a moment to survey the environment and readjust body position before falling back asleep. Sleepers typically awaken soon after the end of a REM phase or sometimes in the middle of REM. Internal circadian indicators, along with a successful reduction of homeostatic sleep need, typically bring about awakening and the end of the sleep cycle. Awakening involves heightened electrical activation in the brain, beginning with the thalamus and spreading throughout the cortex.

During a night's sleep, a small amount of time is usually spent in a waking state. As measured by electroencephalography, young females are awake for 0–1% of the larger sleeping period; young males are awake for 0–2%. In adults, wakefulness increases, especially in later cycles. One study found 3% awake time in the first ninety-minute sleep cycle, 8% in the second, 10% in the third, 12% in the fourth, and 13–14% in the fifth. Most of this awake time occurred shortly after REM sleep.

Today, many humans wake up with an alarm clock; however, people can also reliably wake themselves up at a specific time with no need for an alarm. Many sleep quite differently on workdays versus days off, a pattern which can lead to chronic circadian desynchronization. Many people regularly look at television and other screens before going to bed, a factor which may exacerbate disruption of the circadian cycle. Scientific studies on sleep have shown that sleep stage at awakening is an important factor in amplifying sleep inertia.

Timing

Sleep timing is controlled by the circadian clock (Process C), sleep-wake homeostasis (Process S), and to some extent by the individual will.

Circadian clock

Sleep timing depends greatly on hormonal signals from the circadian clock, or Process C, a complex neurochemical system which uses signals from an organism's environment to recreate an internal day–night rhythm. Process C counteracts the homeostatic drive for sleep during the day (in diurnal animals) and augments it at night. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a brain area directly above the optic chiasm, is presently considered the most important nexus for this process; however, secondary clock systems have been found throughout the body.

An organism whose circadian clock exhibits a regular rhythm corresponding to outside signals is said to be entrained; an entrained rhythm persists even if the outside signals suddenly disappear. If an entrained human is isolated in a bunker with constant light or darkness, he or she will continue to experience rhythmic increases and decreases of body temperature and melatonin, on a period that slightly exceeds 24 hours. Scientists refer to such conditions as free-running of the circadian rhythm. Under natural conditions, light signals regularly adjust this period downward, so that it corresponds better with the exact 24 hours of an Earth day.

The circadian clock exerts constant influence on the body, affecting sinusoidal oscillation of body temperature between roughly 36.2 °C and 37.2 °C. The suprachiasmatic nucleus itself shows conspicuous oscillation activity, which intensifies during subjective day (i.e., the part of the rhythm corresponding with daytime, whether accurately or not) and drops to almost nothing during subjective night. The circadian pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus has a direct neural connection to the pineal gland, which releases the hormone melatonin at night. Cortisol levels typically rise throughout the night, peak in the awakening hours, and diminish during the day. Circadian prolactin secretion begins in the late afternoon, especially in women, and is subsequently augmented by sleep-induced secretion, to peak in the middle of the night. Circadian rhythm exerts some influence on the nighttime secretion of growth hormone.

The circadian rhythm influences the ideal timing of a restorative sleep episode. Sleepiness increases during the night. REM sleep occurs more during body temperature minimum within the circadian cycle, whereas slow-wave sleep can occur more independently of circadian time.

The internal circadian clock is profoundly influenced by changes in light, since these are its main clues about what time it is. Exposure to even small amounts of light during the night can suppress melatonin secretion, and increase body temperature and wakefulness. Short pulses of light, at the right moment in the circadian cycle, can significantly 'reset' the internal clock. Blue light, in particular, exerts the strongest effect, leading to concerns that electronic media use before bed may interfere with sleep.

Modern humans often find themselves desynchronized from their internal circadian clock, due to the requirements of work (especially night shifts), long-distance travel, and the influence of universal indoor lighting. Even if they have sleep debt, or feel sleepy, people can have difficulty staying asleep at the peak of their circadian cycle. Conversely, they can have difficulty waking up in the trough of the cycle. A healthy young adult entrained to the sun will (during most of the year) fall asleep a few hours after sunset, experience body temperature minimum at 6 a.m., and wake up a few hours after sunrise.

Process S

Generally speaking, the longer an organism is awake, the more it feels a need to sleep ("sleep debt"). This driver of sleep is referred to as Process S. The balance between sleeping and waking is regulated by a process called homeostasis. Induced or perceived lack of sleep is called sleep deprivation.

Process S is driven by the depletion of glycogen and accumulation of adenosine in the forebrain that disinhibits the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, allowing for inhibition of the ascending reticular activating system.

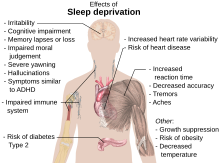

Sleep deprivation tends to cause slower brain waves in the frontal cortex, shortened attention span, higher anxiety, impaired memory, and a grouchy mood. Conversely, a well-rested organism tends to have improved memory and mood. Neurophysiological and functional imaging studies have demonstrated that frontal regions of the brain are particularly responsive to homeostatic sleep pressure.

There is disagreement on how much sleep debt is possible to accumulate, and whether sleep debt is accumulated against an individual's average sleep or some other benchmark. It is also unclear whether the prevalence of sleep debt among adults has changed appreciably in the industrialized world in recent decades. Sleep debt does show some evidence of being cumulative. Subjectively, however, humans seem to reach maximum sleepiness after 30 hours of waking up. It is likely that in Western societies, children are sleeping less than they previously have.

One neurochemical indicator of sleep debt is adenosine, a neurotransmitter that inhibits many of the bodily processes associated with wakefulness. Adenosine levels increase in the cortex and basal forebrain during prolonged wakefulness, and decrease during the sleep-recovery period, potentially acting as a homeostatic regulator of sleep. Coffee and caffeine temporarily block the effect of adenosine, prolong sleep latency, and reduce total sleep time and quality.

Social timing

Humans are also influenced by aspects of social time, such as the hours when other people are awake, the hours when work is required, the time on the clock, etc. Time zones, standard times used to unify the timing for people in the same area, correspond only approximately to the natural rising and setting of the sun. The approximate nature of the time zone can be shown with China, a country which used to span five time zones and now officially uses only one (UTC+8).

Distribution

In polyphasic sleep, an organism sleeps several times in a 24-hour cycle, whereas in monophasic sleep this occurs all at once. Under experimental conditions, humans tend to alternate more frequently between sleep and wakefulness (i.e., exhibit more polyphasic sleep) if they have nothing better to do. Given a 14-hour period of darkness in experimental conditions, humans tended towards bimodal sleep, with two sleep periods concentrated at the beginning and at the end of the dark time. Bimodal sleep in humans was more common before the industrial revolution.

Different characteristic sleep patterns, such as the familiarly so-called "early bird" and "night owl", are called chronotypes. Genetics and sex have some influence on chronotype, but so do habits. Chronotype is also liable to change over the course of a person's lifetime. Seven-year-olds are better disposed to wake up early in the morning than are fifteen-year-olds. Chronotypes far outside the normal range are called circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

Naps

The siesta habit has recently been associated with a 37% lower coronary mortality, possibly due to reduced cardiovascular stress mediated by daytime sleep. Short naps at mid-day and mild evening exercise were found to be effective for improved sleep, cognitive tasks, and mental health in elderly people.

Genetics

Monozygotic (identical) but not dizygotic (fraternal) twins tend to have similar sleep habits. Neurotransmitters, molecules whose production can be traced to specific genes, are one genetic influence on sleep that can be analyzed. The circadian clock has its own set of genes. Genes which may influence sleep include ABCC9, DEC2, Dopamine receptor D2[41] and variants near PAX 8 and VRK2.

Quality

The quality of sleep may be evaluated from an objective and a subjective point of view. Objective sleep quality refers to how difficult it is for a person to fall asleep and remain in a sleeping state, and how many times they wake up during a single night. Poor sleep quality disrupts the cycle of transition between the different stages of sleep. Subjective sleep quality in turn refers to a sense of being rested and regenerated after awaking from sleep. A study by A. Harvey et al. (2002) found that insomniacs were more demanding in their evaluations of sleep quality than individuals who had no sleep problems.

Homeostatic sleep propensity (the need for sleep as a function of the amount of time elapsed since the last adequate sleep episode) must be balanced against the circadian element for satisfactory sleep. Along with corresponding messages from the circadian clock, this tells the body it needs to sleep. The timing is correct when the following two circadian markers occur after the middle of the sleep episode and before awakening: maximum concentration of the hormone melatonin, and minimum core body temperature.

Ideal duration

Human sleep-needs vary by age and amongst individuals; sleep is considered to be adequate when there is no daytime sleepiness or dysfunction. Moreover, self-reported sleep duration is only moderately correlated with actual sleep time as measured by actigraphy, and those affected with sleep state misperception may typically report having slept only four hours despite having slept a full eight hours.

Researchers have found that sleeping 6–7 hours each night correlates with longevity and cardiac health in humans, though many underlying factors may be involved in the causality behind this relationship.

Sleep difficulties are furthermore associated with psychiatric disorders such as depression, alcoholism, and bipolar disorder. Up to 90 percent of adults with depression are found to have sleep difficulties. Dysregulation detected by EEG includes disturbances in sleep continuity, decreased delta sleep and altered REM patterns with regard to latency, distribution across the night and density of eye movements.

Sleep duration can also vary according to season. Up to 90% of people report longer sleep duration in winter, which may lead to more pronounced seasonal affective disorder.

Children

By the time infants reach the age of two, their brain size has reached 90 percent of an adult-sized brain; a majority of this brain growth has occurred during the period of life with the highest rate of sleep. The hours that children spend asleep influence their ability to perform on cognitive tasks. Children who sleep through the night and have few night waking episodes have higher cognitive attainments and easier temperaments than other children.

Sleep also influences language development. To test this, researchers taught infants a faux language and observed their recollection of the rules for that language. Infants who slept within four hours of learning the language could remember the language rules better, while infants who stayed awake longer did not recall those rules as well. There is also a relationship between infants' vocabulary and sleeping: infants who sleep longer at night at 12 months have better vocabularies at 26 months.

Recommendations

Children need many hours of sleep per day in order to develop and function properly: up to 18 hours for newborn babies, with a declining rate as a child ages. Early in 2015, after a two-year study, the National Sleep Foundation in the US announced newly-revised recommendations as shown in the table below.

| Age and condition | Sleep needs |

|---|---|

| Newborns (0–3 months) | 14 to 17 hours |

| Infants (4–11 months) | 12 to 15 hours |

| Toddlers (1–2 years) | 11 to 14 hours |

| Preschoolers (3–4 years) | 10 to 13 hours |

| School-age children (5–12 years) | 9 to 11 hours |

| Teenagers (13–17 years) | 8 to 10 hours |

| Adults (18–64 years) | 7 to 9 hours |

| Older Adults (65 years and over) | 7 to 8 hours |

Functions

Restoration

The human organism physically restores itself during sleep, occurring mostly during slow-wave sleep during which body temperature, heart rate, and brain oxygen consumption decrease. In both the brain and body, the reduced rate of metabolism enables countervailing restorative processes. The brain requires sleep for restoration, whereas these processes can take place during quiescent waking in the rest of the body. The essential function of sleep may be its restorative effect on the brain: "Sleep is of the brain, by the brain and for the brain." This theory is strengthened by the fact that sleep is observed to be a necessary behavior across most of the animal kingdom, including some of the least evolved animals which have no need for other functions of sleep, such as memory consolidation or dreaming.

While awake, brain metabolism generates end products, such as reactive oxygen species, which may be damaging to brain cells and inhibit their proper function. During sleep, metabolic rates decrease and reactive oxygen species generation is reduced, enabling restorative processes. The sleeping brain has been shown to remove metabolic end products at a faster rate than during an awake state. The mechanism for this removal appears to be the glymphatic system. Sleep may facilitate the synthesis of molecules that help repair and protect the brain from metabolic end products generated during waking. Anabolic hormones, such as growth hormones, are secreted preferentially during sleep. The brain concentration of glycogen increases during sleep, and is depleted through metabolism during wakefulness.

The effect of sleep duration on somatic growth is not completely known. One study recorded growth, height, and weight, as correlated to parent-reported time in bed in 305 children over a period of nine years (age 1–10). It was found that "the variation of sleep duration among children does not seem to have an effect on growth." Slow-wave sleep affects growth hormone levels in adult men. During eight hours of sleep, men with a high percentage of slow-wave sleep (SWS) (average 24%) also had high growth hormone secretion, while subjects with a low percentage of SWS (average 9%) had low growth hormone secretion.

Memory processing

It has been widely accepted that sleep must support the formation of long-term memory, and generally increasing previous learning and experiences recalls. However, its benefit seems to depend on the phase of sleep and the type of memory. For example, declarative and procedural memory-recall tasks applied over early and late nocturnal sleep, as well as wakefulness controlled conditions, have been shown that declarative memory improves more during early sleep (dominated by SWS) while procedural memory during late sleep (dominated by REM sleep) does so.

With regard to declarative memory, the functional role of SWS has been associated with hippocampal replays of previously encoded neural patterns that seem to facilitate long-term memory consolidation. This assumption is based on the active system consolidation hypothesis, which states that repeated reactivations of newly-encoded information in the hippocampus during slow oscillations in NREM sleep mediate the stabilization and gradual integration of declarative memory with pre-existing knowledge networks on the cortical level. It assumes the hippocampus might hold information only temporarily and in a fast-learning rate, whereas the neocortex is related to long-term storage and a slow-learning rate. This dialogue between the hippocampus and neocortex occurs in parallel with hippocampal sharp-wave ripples and thalamo-cortical spindles, synchrony that drives the formation of the spindle-ripple event which seems to be a prerequisite for the formation of long-term memories.

Reactivation of memory also occurs during wakefulness and its function is associated with serving to update the reactivated memory with newly-encoded information, whereas reactivations during SWS are presented as crucial for memory stabilization. Based on targeted memory reactivation (TMR) experiments that use associated memory cues to triggering memory traces during sleep, several studies have been reassuring the importance of nocturnal reactivations for the formation of persistent memories in neocortical networks, as well as highlighting the possibility of increasing people’s memory performance at declarative recalls.

Furthermore, nocturnal reactivation seems to share the same neural oscillatory patterns as reactivation during wakefulness, processes which might be coordinated by theta activity. During wakefulness, theta oscillations have been often related to successful performance in memory tasks, and cued memory reactivations during sleep have been showing that theta activity is significantly stronger in subsequent recognition of cued stimuli as compared to uncued ones, possibly indicating a strengthening of memory traces and lexical integration by cuing during sleep. However, the beneficial effect of TMR for memory consolidation seems to occur only if the cued memories can be related to prior knowledge.

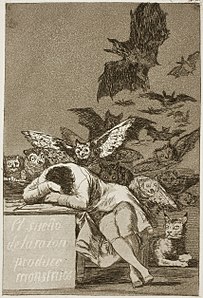

Dreaming

During sleep, especially REM sleep, humans tend to experience dreams. These are elusive and mostly unpredictable first-person experiences which seem logical and realistic to the dreamer while they are in progress, despite their frequently bizarre, irrational, and/or surreal qualities that become apparent when assessed after waking. Dreams often seamlessly incorporate concepts, situations, people, and objects within a person's mind that would not normally go together. They can include apparent sensations of all types, especially vision and movement.

Dreams tend to rapidly fade from memory after waking. Some people choose to keep a dream journal, which they believe helps them build dream recall and facilitate the ability to experience lucid dreams.

People have proposed many hypotheses about the functions of dreaming. Sigmund Freud postulated that dreams are the symbolic expression of frustrated desires that have been relegated to the unconscious mind, and he used dream interpretation in the form of psychoanalysis in attempting to uncover these desires.

Counterintuitively, penile erections during sleep are not more frequent during sexual dreams than during other dreams. The parasympathetic nervous system experiences increased activity during REM sleep which may cause erection of the penis or clitoris. In males, 80% to 95% of REM sleep is normally accompanied by partial to full penile erection, while only about 12% of men's dreams contain sexual content.

John Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley propose that dreams are caused by the random firing of neurons in the cerebral cortex during the REM period. Neatly, this theory helps explain the irrationality of the mind during REM periods, as, according to this theory, the forebrain then creates a story in an attempt to reconcile and make sense of the nonsensical sensory information presented to it. This would explain the odd nature of many dreams.

Using antidepressants, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or alcoholic beverages is thought to potentially suppress dreams, whereas melatonin may have the ability to encourage them.

Disorders

Insomnia

Insomnia is a general term for difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep. Insomnia is the most common sleep problem, with many adults reporting occasional insomnia, and 10–15% reporting a chronic condition. Insomnia can have many different causes, including psychological stress, a poor sleep environment, an inconsistent sleep schedule, or excessive mental or physical stimulation in the hours before bedtime. Insomnia is often treated through behavioral changes like keeping a regular sleep schedule, avoiding stimulating or stressful activities before bedtime, and cutting down on stimulants such as caffeine. The sleep environment may be improved by installing heavy drapes to shut out all sunlight, and keeping computers, televisions, and work materials out of the sleeping area.

A 2010 review of published scientific research suggested that exercise generally improves sleep for most people, and helps sleep disorders such as insomnia. The optimum time to exercise may be 4 to 8 hours before bedtime, though exercise at any time of day is beneficial, with the exception of heavy exercise taken shortly before bedtime, which may disturb sleep. However, there is insufficient evidence to draw detailed conclusions about the relationship between exercise and sleep. Sleeping medications such as Ambien and Lunesta are an increasingly popular treatment for insomnia. Although these nonbenzodiazepine medications are generally believed to be better and safer than earlier generations of sedatives, they have still generated some controversy and discussion regarding side effects. White noise appears to be a promising treatment for insomnia.

Obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea is a condition in which major pauses in breathing occur during sleep, disrupting the normal progression of sleep and often causing other more severe health problems. Apneas occur when the muscles around the patient's airway relax during sleep, causing the airway to collapse and block the intake of oxygen. Obstructive sleep apnea is more common than central sleep apnea. As oxygen levels in the blood drop, the patient then comes out of deep sleep in order to resume breathing. When several of these episodes occur per hour, sleep apnea rises to a level of seriousness that may require treatment.

Diagnosing sleep apnea usually requires a professional sleep study performed in a sleep clinic, because the episodes of wakefulness caused by the disorder are extremely brief and patients usually do not remember experiencing them. Instead, many patients simply feel tired after getting several hours of sleep and have no idea why. Major risk factors for sleep apnea include chronic fatigue, old age, obesity, and snoring.

Aging and sleep

People over age 60 with prolonged sleep (8-10 hours or more; average sleep duration of 7-8 hours in the elderly) have a 33% increased risk of all-cause mortality and 43% increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, while those with short sleep (less than 7 hours) have a 6% increased risk of all-cause mortality. Sleep disorders, including sleep apnea, insomnia, or periodic limb movements, occur more commonly in the elderly, each possibly impacting sleep quality and duration. A 2017 review indicated that older adults do not need less sleep, but rather have an impaired ability to obtain their sleep needs, and may be able to deal with sleepiness better than younger adults. Various practices are recommended to mitigate sleep disturbances in the elderly, such as having a light bedtime snack, avoidance of caffeine, daytime naps, excessive evening stimulation, and tobacco products, and using regular bedtime and wake schedules.

Other disorders

Sleep disorders include narcolepsy, periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), restless leg syndrome (RLS), upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS), and the circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Fatal familial insomnia, or FFI, an extremely rare genetic disease with no known treatment or cure, is characterized by increasing insomnia as one of its symptoms; ultimately sufferers of the disease stop sleeping entirely, before dying of the disease.

Somnambulism, known as sleepwalking, is a sleeping disorder, especially among children.

Sleep health

Low quality sleep has been linked with health conditions like cardiovascular disease, obesity, and mental illness. While poor sleep is common among those with cardiovascular disease, some research indicates that poor sleep can be a contributing cause. Short sleep duration of less than seven hours is correlated with coronary heart disease and increased risk of death from coronary heart disease. Sleep duration greater than nine hours is also correlated with coronary heart disease, as well as stroke and cardiovascular events.

In both children and adults, short sleep duration is associated with an increased risk of obesity, with various studies reporting an increased risk of 45–55%. Other aspects of sleep health have been associated with obesity, including daytime napping, sleep timing, the variability of sleep timing, and low sleep efficiency. However, sleep duration is the most-studied for its impact on obesity.

Sleep problems have been frequently viewed as a symptom of mental illness rather than a causative factor. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that they are both a cause and a symptom of mental illness. Insomnia is a significant predictor of major depressive disorder; a meta-analysis of 170,000 people showed that insomnia at the beginning of a study period indicated a more than the twofold increased risk for major depressive disorder. Some studies have also indicated correlation between insomnia and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. Sleep disorders can increase the risk of psychosis and worsen the severity of psychotic episodes.

Sleep research also displays differences in race and class. Short sleep and poor sleep are observed more frequently in ethnic minorities than in whites. African-Americans report experiencing short durations of sleep five times more often than whites, possibly as a result of social and environmental factors. Black children and children in disadvantaged neighborhoods have much higher rates of sleep apnea than white children and respond more poorly to treatment.

Drugs and diet

Drugs which induce sleep, known as hypnotics, include benzodiazepines, although these interfere with REM; Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics such as eszopiclone (Lunesta), zaleplon (Sonata), and zolpidem (Ambien); antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and doxylamine; alcohol (ethanol), despite its rebound effect later in the night and interference with REM; barbiturates, which have the same problem; melatonin, a component of the circadian clock, and released naturally at night by the pineal gland; and cannabis, which may also interfere with REM.

Stimulants, which inhibit sleep, include caffeine, an adenosine antagonist; amphetamine, MDMA, empathogen-entactogens, and related drugs; cocaine, which can alter the circadian rhythm, and methylphenidate, which acts similarly; and other analeptic drugs like modafinil and armodafinil with poorly understood mechanisms.

Dietary and nutritional choices may affect sleep duration and quality. One 2016 review indicated that a high-carbohydrate diet promoted a shorter onset to sleep and a longer duration of sleep than a high-fat diet. A 2012 investigation indicated that mixed micronutrients and macronutrients are needed to promote quality sleep. A varied diet containing fresh fruits and vegetables, low saturated fat, and whole grains may be optimal for individuals seeking to improve sleep quality. High-quality clinical trials on long-term dietary practices are needed to better define the influence of diet on sleep quality.

In culture

Anthropology

Research suggests that sleep patterns vary significantly across cultures. The most striking differences are observed between societies that have plentiful sources of artificial light and ones that do not. The primary difference appears to be that pre-light cultures have more broken-up sleep patterns. For example, people without artificial light might go to sleep far sooner after the sun sets, but then wake up several times throughout the night, punctuating their sleep with periods of wakefulness, perhaps lasting several hours.

The boundaries between sleeping and waking are blurred in these societies. Some observers believe that nighttime sleep in these societies is most often split into two main periods, the first characterized primarily by deep sleep and the second by REM sleep.

Some societies display a fragmented sleep pattern in which people sleep at all times of the day and night for shorter periods. In many nomadic or hunter-gatherer societies, people will sleep on and off throughout the day or night depending on what is happening. Plentiful artificial light has been available in the industrialized West since at least the mid-19th century, and sleep patterns have changed significantly everywhere that lighting has been introduced. In general, people sleep in a more concentrated burst through the night, going to sleep much later, although this is not always the case.

Historian A. Roger Ekirch thinks that the traditional pattern of "segmented sleep," as it is called, began to disappear among the urban upper class in Europe in the late 17th century and the change spread over the next 200 years; by the 1920s "the idea of a first and second sleep had receded entirely from our social consciousness." Ekirch attributes the change to increases in "street lighting, domestic lighting and a surge in coffee houses," which slowly made nighttime a legitimate time for activity, decreasing the time available for rest. Today in most societies people sleep during the night, but in very hot climates they may sleep during the day. During Ramadan, many Muslims sleep during the day rather than at night.

In some societies, people sleep with at least one other person (sometimes many) or with animals. In other cultures, people rarely sleep with anyone except for an intimate partner. In almost all societies, sleeping partners are strongly regulated by social standards. For example, a person might only sleep with the immediate family, the extended family, a spouse or romantic partner, children, children of a certain age, children of a specific gender, peers of a certain gender, friends, peers of equal social rank, or with no one at all. Sleep may be an actively social time, depending on the sleep groupings, with no constraints on noise or activity.

People sleep in a variety of locations. Some sleep directly on the ground; others on a skin or blanket; others sleep on platforms or beds. Some sleep with blankets, some with pillows, some with simple headrests, some with no head support. These choices are shaped by a variety of factors, such as climate, protection from predators, housing type, technology, personal preference, and the incidence of pests.

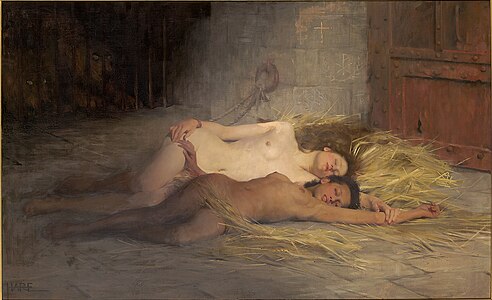

In mythology and literature

Sleep has been seen in culture as similar to death since antiquity; in Greek mythology, Hypnos (the god of sleep) and Thanatos (the god of death) were both said to be the children of Nyx (the goddess of night). John Donne, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and other poets have all written poems about the relationship between sleep and death. Shelley describes them as "both so passing, strange and wonderful!" Many people consider dying in one's sleep the most peaceful way to die. Phrases such as "big sleep" and "rest in peace" are often used in reference to death, possibly in an effort to lessen its finality. Sleep and dreaming have sometimes been seen as providing the potential for visionary experiences. In medieval Irish tradition, in order to become a filí, the poet was required to undergo a ritual called the imbas forosnai, in which they would enter a mantic, trancelike sleep.

Many cultural stories have been told about people falling asleep for extended periods of time. The earliest of these stories is the ancient Greek legend of Epimenides of Knossos. According to the biographer Diogenes Laërtius, Epimenides was a shepherd on the Greek island of Crete. One day, one of his sheep went missing and he went out to look for it, but became tired and fell asleep in a cave under Mount Ida. When he awoke, he continued searching for the sheep, but could not find it, so he returned to his old farm, only to discover that it was now under new ownership. He went to his hometown, but discovered that nobody there knew him. Finally, he met his younger brother, who was now an old man, and learned that he had been asleep in the cave for fifty-seven years.

A far more famous instance of a "long sleep" today is the Christian legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, in which seven Christians flee into a cave during pagan times in order to escape persecution, but fall asleep and wake up 360 years later to discover, to their astonishment, that the Roman Empire is now predominantly Christian. The American author Washington Irving's short story "Rip Van Winkle", first published in 1819 in his collection of short stories The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., is about a man in colonial America named Rip Van Winkle who falls asleep on one of the Catskill Mountains and wakes up twenty years later after the American Revolution. The story is now considered one of the greatest classics of American literature.

In art

Of the thematic representations of sleep in art, physician and sleep researcher Meir Kryger wrote, "[Artists] have intense fascination with mythology, dreams, religious themes, the parallel between sleep and death, reward, abandonment of conscious control, healing, a depiction of innocence and serenity, and the erotic."

The Sentry (1654) by Carel Fabritius

Diana and Endymion (c. 1822) by Jérôme-Martin Langlois

The Second Class Carriage (1864) by Honoré Daumier

Lullaby (1875) by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Taking a Rest (1882) by Ilya Repin

Victory of Faith (1889) by Saint George Hare

Zwei schlafende Mädchen auf der Ofenbank (1895) by Albert Anker

Flaming June (c. 1895) by Frederic Lord Leighton

Noon – Rest from Work (1890) by Vincent van Gogh (after Millet)

Sleeping Jaguar, by Paul Klimsch

Sleeping Girl on a Wooden Bench by Albert Anker

Chrapek (Snorer), Wrocław's dwarfs