Flywheel energy storage (FES) works by accelerating a rotor (flywheel) to a very high speed and maintaining the energy in the system as rotational energy. When energy is extracted from the system, the flywheel's rotational speed is reduced as a consequence of the principle of conservation of energy; adding energy to the system correspondingly results in an increase in the speed of the flywheel.

Most FES systems use electricity to accelerate and decelerate the flywheel, but devices that directly use mechanical energy are being developed.

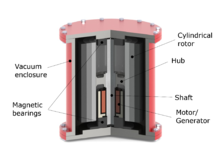

Advanced FES systems have rotors made of high strength carbon-fiber composites, suspended by magnetic bearings, and spinning at speeds from 20,000 to over 50,000 rpm in a vacuum enclosure. Such flywheels can come up to speed in a matter of minutes – reaching their energy capacity much more quickly than some other forms of storage.

Main components

A typical system consists of a flywheel supported by rolling-element bearing connected to a motor–generator. The flywheel and sometimes motor–generator may be enclosed in a vacuum chamber to reduce friction and reduce energy loss.

First-generation flywheel energy-storage systems use a large steel flywheel rotating on mechanical bearings. Newer systems use carbon-fiber composite rotors that have a higher tensile strength than steel and can store much more energy for the same mass.

To reduce friction, magnetic bearings are sometimes used instead of mechanical bearings.

Possible future use of superconducting bearings

The expense of refrigeration led to the early dismissal of low-temperature superconductors for use in magnetic bearings. However, high-temperature superconductor (HTSC) bearings may be economical and could possibly extend the time energy could be stored economically. Hybrid bearing systems are most likely to see use first. High-temperature superconductor bearings have historically had problems providing the lifting forces necessary for the larger designs but can easily provide a stabilizing force. Therefore, in hybrid bearings, permanent magnets support the load and high-temperature superconductors are used to stabilize it. The reason superconductors can work well stabilizing the load is because they are perfect diamagnets. If the rotor tries to drift off-center, a restoring force due to flux pinning restores it. This is known as the magnetic stiffness of the bearing. Rotational axis vibration can occur due to low stiffness and damping, which are inherent problems of superconducting magnets, preventing the use of completely superconducting magnetic bearings for flywheel applications.

Since flux pinning is an important factor for providing the stabilizing and lifting force, the HTSC can be made much more easily for FES than for other uses. HTSC powders can be formed into arbitrary shapes so long as flux pinning is strong. An ongoing challenge that has to be overcome before superconductors can provide the full lifting force for an FES system is finding a way to suppress the decrease of levitation force and the gradual fall of rotor during operation caused by the flux creep of the superconducting material.

Physical characteristics

General

Compared with other ways to store electricity, FES systems have long lifetimes (lasting decades with little or no maintenance; full-cycle lifetimes quoted for flywheels range from in excess of 105, up to 107, cycles of use), high specific energy (100–130 W·h/kg, or 360–500 kJ/kg), and large maximum power output. The energy efficiency (ratio of energy out per energy in) of flywheels, also known as round-trip efficiency, can be as high as 90%. Typical capacities range from 3 kWh to 133 kWh. Rapid charging of a system occurs in less than 15 minutes. The high specific energies often cited with flywheels can be a little misleading as commercial systems built have much lower specific energy, for example 11 W·h/kg, or 40 kJ/kg.

Form of energy storage

Here is the integral of the flywheel's mass, and is the rotational speed (number of revolutions per second).

Specific energy

The maximal specific energy of a flywheel rotor is mainly dependent on two factors: the first being the rotor's geometry, and the second being the properties of the material being used. For single-material, isotropic rotors this relationship can be expressed as

where

- is kinetic energy of the rotor [J],

- is the rotor's mass [kg],

- is the rotor's geometric shape factor [dimensionless],

- is the tensile strength of the material [Pa],

- is the material's density [kg/m3].

Geometry (shape factor)

The highest possible value for the shape factor of a flywheel rotor, is , which can be achieved only by the theoretical constant-stress disc geometry. A constant-thickness disc geometry has a shape factor of , while for a rod of constant thickness the value is . A thin cylinder has a shape factor of . For most flywheels with a shaft, the shape factor is below or about . A shaft-less design has a shape factor similar to a constant-thickness disc (), which enables a doubled energy density.

Material properties

For energy storage, materials with high strength and low density are desirable. For this reason, composite materials are frequently used in advanced flywheels. The strength-to-density ratio of a material can be expressed in Wh/kg (or Nm/kg); values greater than 400 Wh/kg can be achieved by certain composite materials.

Rotor materials

Several modern flywheel rotors are made from composite materials. Examples include the carbon-fiber composite flywheel from Beacon Power Corporation and the PowerThru flywheel from Phillips Service Industries. Alternatively, Calnetix utilizes aerospace-grade high-performance steel in their flywheel construction.

For these rotors, the relationship between material properties, geometry and energy density can be expressed by using a weighed-average approach.

Tensile strength and failure modes

One of the primary limits to flywheel design is the tensile strength of the rotor. Generally speaking, the stronger the disc, the faster it may be spun, and the more energy the system can store. (Making the flywheel heavier without a corresponding increase in strength will slow the maximum speed the flywheel can spin without rupturing, hence will not increase the total amount of energy the flywheel can store.)

When the tensile strength of a composite flywheel's outer binding cover is exceeded, the binding cover will fracture, and the wheel will shatter as the outer wheel compression is lost around the entire circumference, releasing all of its stored energy at once; this is commonly referred to as "flywheel explosion" since wheel fragments can reach kinetic energy comparable to that of a bullet. Composite materials that are wound and glued in layers tend to disintegrate quickly, first into small-diameter filaments that entangle and slow each other, and then into red-hot powder; a cast metal flywheel throws off large chunks of high-speed shrapnel.

For a cast metal flywheel, the failure limit is the binding strength of the grain boundaries of the polycrystalline molded metal. Aluminum in particular suffers from fatigue and can develop microfractures from repeated low-energy stretching. Angular forces may cause portions of a metal flywheel to bend outward and begin dragging on the outer containment vessel, or to separate completely and bounce randomly around the interior. The rest of the flywheel is now severely unbalanced, which may lead to rapid bearing failure from vibration, and sudden shock fracturing of large segments of the flywheel.

Traditional flywheel systems require strong containment vessels as a safety precaution, which increases the total mass of the device. The energy release from failure can be dampened with a gelatinous or encapsulated liquid inner housing lining, which will boil and absorb the energy of destruction. Still, many customers of large-scale flywheel energy-storage systems prefer to have them embedded in the ground to halt any material that might escape the containment vessel.

Energy storage efficiency

Flywheel energy storage systems using mechanical bearings can lose 20% to 50% of their energy in two hours. Much of the friction responsible for this energy loss results from the flywheel changing orientation due to the rotation of the earth (an effect similar to that shown by a Foucault pendulum). This change in orientation is resisted by the gyroscopic forces exerted by the flywheel's angular momentum, thus exerting a force against the mechanical bearings. This force increases friction. This can be avoided by aligning the flywheel's axis of rotation parallel to that of the earth's axis of rotation.

Conversely, flywheels with magnetic bearings and high vacuum can maintain 97% mechanical efficiency, and 85% round trip efficiency.

Effects of angular momentum in vehicles

When used in vehicles, flywheels also act as gyroscopes, since their angular momentum is typically of a similar order of magnitude as the forces acting on the moving vehicle. This property may be detrimental to the vehicle's handling characteristics while turning or driving on rough ground; driving onto the side of a sloped embankment may cause wheels to partially lift off the ground as the flywheel opposes sideways tilting forces. On the other hand, this property could be utilized to keep the car balanced so as to keep it from rolling over during sharp turns.

When a flywheel is used entirely for its effects on the attitude of a vehicle, rather than for energy storage, it is called a reaction wheel or a control moment gyroscope.

The resistance of angular tilting can be almost completely removed by mounting the flywheel within an appropriately applied set of gimbals, allowing the flywheel to retain its original orientation without affecting the vehicle (see Properties of a gyroscope). This doesn't avoid the complication of gimbal lock, and so a compromise between the number of gimbals and the angular freedom is needed.

The center axle of the flywheel acts as a single gimbal, and if aligned vertically, allows for the 360 degrees of yaw in a horizontal plane. However, for instance driving up-hill requires a second pitch gimbal, and driving on the side of a sloped embankment requires a third roll gimbal.

Full-motion gimbals

Although the flywheel itself may be of a flat ring shape, a free-movement gimbal mounting inside a vehicle requires a spherical volume for the flywheel to freely rotate within. Left to its own, a spinning flywheel in a vehicle would slowly precess following the Earth's rotation, and precess further yet in vehicles that travel long distances over the Earth's curved spherical surface.

A full-motion gimbal has additional problems of how to communicate power into and out of the flywheel, since the flywheel could potentially flip completely over once a day, precessing as the Earth rotates. Full free rotation would require slip rings around each gimbal axis for power conductors, further adding to the design complexity.

Limited-motion gimbals

To reduce space usage, the gimbal system may be of a limited-movement design, using shock absorbers to cushion sudden rapid motions within a certain number of degrees of out-of-plane angular rotation, and then gradually forcing the flywheel to adopt the vehicle's current orientation. This reduces the gimbal movement space around a ring-shaped flywheel from a full sphere, to a short thickened cylinder, encompassing for example ± 30 degrees of pitch and ± 30 degrees of roll in all directions around the flywheel.

Counterbalancing of angular momentum

An alternative solution to the problem is to have two joined flywheels spinning synchronously in opposite directions. They would have a total angular momentum of zero and no gyroscopic effect. A problem with this solution is that when the difference between the momentum of each flywheel is anything other than zero the housing of the two flywheels would exhibit torque. Both wheels must be maintained at the same speed to keep the angular velocity at zero. Strictly speaking, the two flywheels would exert a huge torqueing moment at the central point, trying to bend the axle. However, if the axle were sufficiently strong, no gyroscopic forces would have a net effect on the sealed container, so no torque would be noticed.

To further balance the forces and spread out strain, a single large flywheel can be balanced by two half-size flywheels on each side, or the flywheels can be reduced in size to be a series of alternating layers spinning in opposite directions. However this increases housing and bearing complexity.

Applications

Transportation

Automotive

In the 1950s, flywheel-powered buses, known as gyrobuses, were used in Yverdon (Switzerland) and Ghent (Belgium) and there is ongoing research to make flywheel systems that are smaller, lighter, cheaper and have a greater capacity. It is hoped that flywheel systems can replace conventional chemical batteries for mobile applications, such as for electric vehicles. Proposed flywheel systems would eliminate many of the disadvantages of existing battery power systems, such as low capacity, long charge times, heavy weight and short usable lifetimes. Flywheels may have been used in the experimental Chrysler Patriot, though that has been disputed.

Flywheels have also been proposed for use in continuously variable transmissions. Punch Powertrain is currently working on such a device.

During the 1990s, Rosen Motors developed a gas turbine powered series hybrid automotive powertrain using a 55,000 rpm flywheel to provide bursts of acceleration which the small gas turbine engine could not provide. The flywheel also stored energy through regenerative braking. The flywheel was composed of a titanium hub with a carbon fiber cylinder and was gimbal-mounted to minimize adverse gyroscopic effects on vehicle handling. The prototype vehicle was successfully road tested in 1997 but was never mass-produced.

In 2013, Volvo announced a flywheel system fitted to the rear axle of its S60 sedan. Braking action spins the flywheel at up to 60,000 rpm and stops the front-mounted engine. Flywheel energy is applied via a special transmission to partially or completely power the vehicle. The 20-centimetre (7.9 in), 6-kilogram (13 lb) carbon fiber flywheel spins in a vacuum to eliminate friction. When partnered with a four-cylinder engine, it offers up to a 25 percent reduction in fuel consumption versus a comparably performing turbo six-cylinder, providing an 80 horsepower (60 kW) boost and allowing it to reach 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph) in 5.5 seconds. The company did not announce specific plans to include the technology in its product line.

In July 2014 GKN acquired Williams Hybrid Power (WHP) division and intends to supply 500 carbon fiber Gyrodrive electric flywheel systems to urban bus operators over the next two years As the former developer name implies, these were originally designed for Formula one motor racing applications. In September 2014, Oxford Bus Company announced that it is introducing 14 Gyrodrive hybrid buses by Alexander Dennis on its Brookes Bus operation.

Rail vehicles

Flywheel systems have been used experimentally in small electric locomotives for shunting or switching, e.g. the Sentinel-Oerlikon Gyro Locomotive. Larger electric locomotives, e.g. British Rail Class 70, have sometimes been fitted with flywheel boosters to carry them over gaps in the third rail. Advanced flywheels, such as the 133 kWh pack of the University of Texas at Austin, can take a train from a standing start up to cruising speed.

The Parry People Mover is a railcar which is powered by a flywheel. It was trialled on Sundays for 12 months on the Stourbridge Town Branch Line in the West Midlands, England during 2006 and 2007 and was intended to be introduced as a full service by the train operator London Midland in December 2008 once two units had been ordered. In January 2010, both units are in operation.

Rail electrification

FES can be used at the lineside of electrified railways to help regulate the line voltage thus improving the acceleration of unmodified electric trains and the amount of energy recovered back to the line during regenerative braking, thus lowering energy bills. Trials have taken place in London, New York, Lyon and Tokyo, and New York MTA's Long Island Rail Road is now investing $5.2m in a pilot project on LIRR's West Hempstead Branch line. These trials and systems store kinetic energy in rotors consisting of a carbon-glass composite cylinder packed with neodymium-iron-boron powder that forms a permanent magnet. These spin at up to 37800rev/min, and each 100 kW unit can store 11 megajoules (3.1 kWh) of re-usable energy, approximately enough to accelerate a weight of 200 metric tons from zero to 38 km/h.

Uninterruptible power supplies

Flywheel power storage systems in production as of 2001 have storage capacities comparable to batteries and faster discharge rates. They are mainly used to provide load leveling for large battery systems, such as an uninterruptible power supply for data centers as they save a considerable amount of space compared to battery systems.

Flywheel maintenance in general runs about one-half the cost of traditional battery UPS systems. The only maintenance is a basic annual preventive maintenance routine and replacing the bearings every five to ten years, which takes about four hours. Newer flywheel systems completely levitate the spinning mass using maintenance-free magnetic bearings, thus eliminating mechanical bearing maintenance and failures.

Costs of a fully installed flywheel UPS (including power conditioning) are (in 2009) about $330 per kilowatt (for 15 seconds full-load capacity).

Test laboratories

A long-standing niche market for flywheel power systems are facilities where circuit breakers and similar devices are tested: even a small household circuit breaker may be rated to interrupt a current of 10000 or more amperes, and larger units may have interrupting ratings of 100000 or 1000000 amperes. The enormous transient loads produced by deliberately forcing such devices to demonstrate their ability to interrupt simulated short circuits would have unacceptable effects on the local grid if these tests were done directly from building power. Typically such a laboratory will have several large motor–generator sets, which can be spun up to speed over several minutes; then the motor is disconnected before a circuit breaker is tested.

Physics laboratories

Tokamak fusion experiments need very high currents for brief intervals (mainly to power large electromagnets for a few seconds).

- JET (the Joint European Torus) has two 775 tonne flywheels (installed in 1981) that spin up to 225 rpm. Each flywheel stores 3.75 GJ and can deliver at up to 400MW.

- The Helically Symmetric Experiment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has 18 one-ton flywheels, which are spun to 10,000 rpm using repurposed electric train motors.

- ASDEX has 3 flywheel generators.

- DIII-D (tokamak) at General Atomics

- the Princeton Large Torus (PLT) at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Also the non-tokamak: Nimrod synchrotron at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory had two 30 ton flywheels.

Aircraft launching systems

The Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carrier will use flywheels to accumulate energy from the ship's power supply, for rapid release into the electromagnetic aircraft launch system. The shipboard power system cannot on its own supply the high power transients necessary to launch aircraft. Each of four rotors will store 121 MJ (34 kWh) at 6400 rpm. They can store 122 MJ (34 kWh) in 45 secs and release it in 2–3 seconds. The flywheel energy densities are 28 kJ/kg (8 W·h/kg); including the stators and cases this comes down to 18.1 kJ/kg (5 W·h/kg), excluding the torque frame.

NASA G2 flywheel for spacecraft energy storage

This was a design funded by NASA's Glenn Research Center and intended for component testing in a laboratory environment. It used a carbon fiber rim with a titanium hub designed to spin at 60,000 rpm, mounted on magnetic bearings. Weight was limited to 250 pounds. Storage was 525 W-hr (1.89 MJ) and could be charged or discharged at 1 kW. The working model shown in the photograph at the top of the page ran at 41,000 rpm on September 2, 2004.

Amusement rides

The Montezooma's Revenge roller coaster at Knott's Berry Farm was the first flywheel-launched roller coaster in the world and is the last ride of its kind still operating in the United States. The ride uses a 7.6 tonnes flywheel to accelerate the train to 55 miles per hour (89 km/h) in 4.5 seconds.

The Incredible Hulk roller coaster at Universal's Islands of Adventure features a rapidly accelerating uphill launch as opposed to the typical gravity drop. This is achieved through powerful traction motors that throw the car up the track. To achieve the brief very high current required to accelerate a full coaster train to full speed uphill, the park utilizes several motor generator sets with large flywheels. Without these stored energy units, the park would have to invest in a new substation or risk browning-out the local energy grid every time the ride launches.

Pulse power

Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS) are found in a variety of applications ranging from grid-connected energy management to uninterruptible power supplies. With the progress of technology, there is fast renovation involved in FESS application. Examples include high power weapons, aircraft powertrains and shipboard power systems, where the system requires a very high-power for a short period in order of a few seconds and even milliseconds. Compensated pulsed alternator (compulsator) is one of the most popular choices of pulsed power supplies for fusion reactors, high-power pulsed lasers, and hypervelocity electromagnetic launchers because of its high energy density and power density, which is generally designed for the FESS. Compulsators (low-inductance alternators) act like capacitors, they can be spun up to provide pulsed power for railguns and lasers. Instead of having a separate flywheel and generator, only the large rotor of the alternator stores energy. See also Homopolar generator.

Motor sports

Using a continuously variable transmission (CVT), energy is recovered from the drive train during braking and stored in a flywheel. This stored energy is then used during acceleration by altering the ratio of the CVT. In motor sports applications this energy is used to improve acceleration rather than reduce carbon dioxide emissions – although the same technology can be applied to road cars to improve fuel efficiency.

Automobile Club de l'Ouest, the organizer behind the annual 24 Hours of Le Mans event and the Le Mans Series, is currently "studying specific rules for LMP1 which will be equipped with a kinetic energy recovery system."

Williams Hybrid Power, a subsidiary of Williams F1 Racing team, have supplied Porsche and Audi with flywheel based hybrid system for Porsche's 911 GT3 R Hybrid and Audi's R18 e-Tron Quattro. Audi's victory in 2012 24 Hours of Le Mans is the first for a hybrid (diesel-electric) vehicle.

Grid energy storage

Flywheels are sometimes used as short term spinning reserve for momentary grid frequency regulation and balancing sudden changes between supply and consumption. No carbon emissions, faster response times and ability to buy power at off-peak hours are among the advantages of using flywheels instead of traditional sources of energy like natural gas turbines. Operation is very similar to batteries in the same application, their differences are primarily economic.

Beacon Power opened a 5 MWh (20 MW over 15 mins) flywheel energy storage plant in Stephentown, New York in 2011 using 200 flywheels and a similar 20 MW system at Hazle Township, Pennsylvania in 2014.

A 2 MW (for 15 min) flywheel storage facility in Minto, Ontario, Canada opened in 2014. The flywheel system (developed by NRStor) uses 10 spinning steel flywheels on magnetic bearings.

Amber Kinetics, Inc. has an agreement with Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) for a 20 MW / 80 MWh flywheel energy storage facility located in Fresno, CA with a four-hour discharge duration.

Wind turbines

Flywheels may be used to store energy generated by wind turbines during off-peak periods or during high wind speeds.

In 2010, Beacon Power began testing of their Smart Energy 25 (Gen 4) flywheel energy storage system at a wind farm in Tehachapi, California. The system was part of a wind power/flywheel demonstration project being carried out for the California Energy Commission.

Toys

Friction motors used to power many toy cars, trucks, trains, action toys and such, are simple flywheel motors.

Toggle action presses

In industry, toggle action presses are still popular. The usual arrangement involves a very strong crankshaft and a heavy duty connecting rod which drives the press. Large and heavy flywheels are driven by electric motors but the flywheels turn the crankshaft only when clutches are activated.

Comparison to electric batteries

Flywheels are not as adversely affected by temperature changes, can operate at a much wider temperature range, and are not subject to many of the common failures of chemical rechargeable batteries. They are also less potentially damaging to the environment, being largely made of inert or benign materials. Another advantage of flywheels is that by a simple measurement of the rotation speed it is possible to know the exact amount of energy stored.

Unlike most batteries which operate only for a finite period (for example roughly 36 months in the case of lithium ion polymer batteries), a flywheel potentially has an indefinite working lifespan. Flywheels built as part of James Watt steam engines have been continuously working for more than two hundred years. Working examples of ancient flywheels used mainly in milling and pottery can be found in many locations in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Most modern flywheels are typically sealed devices that need minimal maintenance throughout their service lives. Magnetic bearing flywheels in vacuum enclosures, such as the NASA model depicted above, do not need any bearing maintenance and are therefore superior to batteries both in terms of total lifetime and energy storage capacity. Flywheel systems with mechanical bearings will have limited lifespans due to wear.

High performance flywheels can explode, killing bystanders with high speed shrapnel. While batteries can catch fire and release toxins, there is generally time for bystanders to flee and escape injury.

The physical arrangement of batteries can be designed to match a wide variety of configurations, whereas a flywheel at a minimum must occupy a certain area and volume, because the energy it stores is proportional to its angular mass and to the square of its rotational speed. As a flywheel gets smaller, its mass also decreases, so the speed must increase, and so the stress on the materials increases. Where dimensions are a constraint, (e.g. under the chassis of a train), a flywheel may not be a viable solution.