| Termite | |

|---|---|

| |

| Formosan subterranean termite (Coptotermes formosanus) Soldiers (red-coloured heads) Workers (pale-coloured heads) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Cohort: | Polyneoptera |

| Superorder: | Dictyoptera |

| Order: | Blattodea |

| Infraorder: | Isoptera Brullé, 1832 |

| Families | |

|

† Cratomastotermitidae | |

Termites are eusocial insects that are classified at the taxonomic rank of infraorder Isoptera, or alternatively as epifamily Termitoidae, within the order Blattodea (along with cockroaches). Termites were once classified in a separate order from cockroaches, but recent phylogenetic studies indicate that they evolved from cockroaches, as they are deeply nested within the group, and the sister group to wood eating cockroaches of the genus Cryptocercus. Previous estimates suggested the divergence took place during the Jurassic or Triassic. More recent estimates suggest they have an origin during the Late Jurassic, with the first fossil records in the Early Cretaceous. About 3,106 species are currently described, with a few hundred more left to be described. Although these insects are often called "white ants", they are not ants, and are not closely related to ants.

Like ants and some bees and wasps from the separate order Hymenoptera, termites divide as "workers" and "soldiers" that are usually sterile. All colonies have fertile males called "kings" and one or more fertile females called "queens". Termites mostly feed on dead plant material and cellulose, generally in the form of wood, leaf litter, soil, or animal dung. Termites are major detritivores, particularly in the subtropical and tropical regions, and their recycling of wood and plant matter is of considerable ecological importance.

Termites are among the most successful groups of insects on Earth, colonising most landmasses except Antarctica. Their colonies range in size from a few hundred individuals to enormous societies with several million individuals. Termite queens have the longest known lifespan of any insect, with some queens reportedly living up to 30 to 50 years. Unlike ants, which undergo a complete metamorphosis, each individual termite goes through an incomplete metamorphosis that proceeds through egg, nymph, and adult stages. Colonies are described as superorganisms because the termites form part of a self-regulating entity: the colony itself.

Termites are a delicacy in the diet of some human cultures and are used in many traditional medicines. Several hundred species are economically significant as pests that can cause serious damage to buildings, crops, or plantation forests. Some species, such as the West Indian drywood termite (Cryptotermes brevis), are regarded as invasive species.

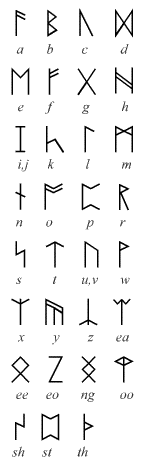

Etymology

The infraorder name Isoptera is derived from the Greek words iso (equal) and ptera (winged), which refers to the nearly equal size of the fore and hind wings. "Termite" derives from the Latin and Late Latin word termes ("woodworm, white ant"), altered by the influence of Latin terere ("to rub, wear, erode") from the earlier word tarmes. A termite nest is also known as a termitary or termitarium (plural termitaria or termitariums). In earlier English, termites were known as "wood ants" or "white ants". The modern term was first used in 1781.

Taxonomy and evolution

Termites were formerly placed in the order Isoptera. As early as 1934 suggestions were made that they were closely related to wood-eating cockroaches (genus Cryptocercus, the woodroach) based on the similarity of their symbiotic gut flagellates. In the 1960s additional evidence supporting that hypothesis emerged when F. A. McKittrick noted similar morphological characteristics between some termites and Cryptocercus nymphs. In 2008 DNA analysis from 16S rRNA sequences supported the position of termites being nested within the evolutionary tree containing the order Blattodea, which included the cockroaches. The cockroach genus Cryptocercus shares the strongest phylogenetical similarity with termites and is considered to be a sister-group to termites. Termites and Cryptocercus share similar morphological and social features: for example, most cockroaches do not exhibit social characteristics, but Cryptocercus takes care of its young and exhibits other social behaviour such as trophallaxis and allogrooming. Termites are thought to be the descendants of the genus Cryptocercus. Some researchers have suggested a more conservative measure of retaining the termites as the Termitoidae, an epifamily within the cockroach order, which preserves the classification of termites at family level and below. Termites have long been accepted to be closely related to cockroaches and mantids, and they are classified in the same superorder (Dictyoptera). The oldest unambiguous termite fossils date to the early Cretaceous, but given the diversity of Cretaceous termites and early fossil records showing mutualism between microorganisms and these insects, they possibly originated earlier in the Jurassic or Triassic. Possible evidence of a Jurassic origin is the assumption that the extinct Fruitafossor consumed termites, judging from its morphological similarity to modern termite-eating mammals. The oldest termite nest discovered is believed to be from the Upper Cretaceous in West Texas, where the oldest known faecal pellets were also discovered. Claims that termites emerged earlier have faced controversy. For example, F. M. Weesner indicated that the Mastotermitidae termites may go back to the Late Permian, 251 million years ago, and fossil wings that have a close resemblance to the wings of Mastotermes of the Mastotermitidae, the most primitive living termite, have been discovered in the Permian layers in Kansas. It is even possible that the first termites emerged during the Carboniferous. The folded wings of the fossil wood roach Pycnoblattina, arranged in a convex pattern between segments 1a and 2a, resemble those seen in Mastotermes, the only living insect with the same pattern. Krishna et al., though, consider that all of the Paleozoic and Triassic insects tentatively classified as termites are in fact unrelated to termites and should be excluded from the Isoptera. Other studies suggest that the origin of termites is more recent, having diverged from Cryptocercus sometime during the Early Cretaceous.

The primitive giant northern termite (Mastotermes darwiniensis) exhibits numerous cockroach-like characteristics that are not shared with other termites, such as laying its eggs in rafts and having anal lobes on the wings. It has been proposed that the Isoptera and Cryptocercidae be grouped in the clade "Xylophagodea". Termites are sometimes called "white ants" but the only resemblance to the ants is due to their sociality which is due to convergent evolution with termites being the first social insects to evolve a caste system more than 100 million years ago. Termite genomes are generally relatively large compared to those of other insects; the first fully sequenced termite genome, of Zootermopsis nevadensis, which was published in the journal Nature Communications, consists of roughly 500Mb, while two subsequently published genomes, Macrotermes natalensis and Cryptotermes secundus, are considerably larger at around 1.3Gb.

As of 2013, about 3,106 living and fossil termite species are recognised, classified in 12 families; reproductive and/or soldier castes are usually required for identification. The infraorder Isoptera is divided into the following clade and family groups, showing the subfamilies in their respective classification:

Basal termite families

- Infraorder Isoptera (= Epifamily Termitoidae)

- Family †Cratomastotermitidae

- Family Mastotermitidae

- Parvorder Euisoptera

- Family †Melqartitermitidae

- Family †Mylacrotermitidae

- Family †Krishnatermitidae

- Family †Termopsidae

- Family †Arceotermitidae

- Family Archotermopsidae

- Family Hodotermitidae

- Family Stolotermitidae

- Family †Tanytermitidae

- Family Kalotermitidae

Neoisoptera

The Neoisoptera, literally meaning "newer termites" (in an evolutionary sense), are a recently coined nanorder that include families commonly referred-to as "higher termites", although some authorities only apply this term to the largest family Termitidae. The latter characteristically do not have Pseudergate nymphs (many "lower termite" worker nymphs have the capacity to develop into reproductive castes: see below). Cellulose digestion in "higher termites" has co-evolved with eukaryotic gut microbiota and many genera have symbiotic relationships with fungi such as Termitomyces; in contrast, "lower termites" typically have flagellates and prokaryotes in their hindguts. Five families are now included here:

|

|

Distribution and diversity

Termites are found on all continents except Antarctica. The diversity of termite species is low in North America and Europe (10 species known in Europe and 50 in North America), but is high in South America, where over 400 species are known. Of the 3,000 termite species currently classified, 1,000 are found in Africa, where mounds are extremely abundant in certain regions. Approximately 1.1 million active termite mounds can be found in the northern Kruger National Park alone. In Asia, there are 435 species of termites, which are mainly distributed in China. Within China, termite species are restricted to mild tropical and subtropical habitats south of the Yangtze River. In Australia, all ecological groups of termites (dampwood, drywood, subterranean) are endemic to the country, with over 360 classified species. Because termites are highly social and abundant, they represent a disproportionate amount of the world's insect biomass. Termites and ants comprise about 1% of insect species, but represent more than 50% of insect biomass.

Due to their soft cuticles, termites do not inhabit cool or cold habitats. There are three ecological groups of termites: dampwood, drywood and subterranean. Dampwood termites are found only in coniferous forests, and drywood termites are found in hardwood forests; subterranean termites live in widely diverse areas. One species in the drywood group is the West Indian drywood termite (Cryptotermes brevis), which is an invasive species in Australia.

|

|

Asia | Africa | North America | South America | Europe | Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated number of species | 435 | 1,000 | 50 | 400 | 10 | 360 |

Description

Termites are usually small, measuring between 4 to 15 millimetres (0.16 to 0.59 in) in length. The largest of all extant termites are the queens of the species Macrotermes bellicosus, measuring up to over 10 centimetres (4 in) in length. Another giant termite, the extinct Gyatermes styriensis, flourished in Austria during the Miocene and had a wingspan of 76 millimetres (3.0 in) and a body length of 25 millimetres (0.98 in).

Most worker and soldier termites are completely blind as they do not have a pair of eyes. However, some species, such as Hodotermes mossambicus, have compound eyes which they use for orientation and to distinguish sunlight from moonlight. The alates (winged males and females) have eyes along with lateral ocelli. Lateral ocelli, however, are not found in all termites, absent in the families Hodotermitidae, Termopsidae, and Archotermopsidae. Like other insects, termites have a small tongue-shaped labrum and a clypeus; the clypeus is divided into a postclypeus and anteclypeus. Termite antennae have a number of functions such as the sensing of touch, taste, odours (including pheromones), heat and vibration. The three basic segments of a termite antenna include a scape, a pedicel (typically shorter than the scape), and the flagellum (all segments beyond the scape and pedicel). The mouth parts contain a maxillae, a labium, and a set of mandibles. The maxillae and labium have palps that help termites sense food and handling.

Consistent with all insects, the anatomy of the termite thorax consists of three segments: the prothorax, the mesothorax and the metathorax. Each segment contains a pair of legs. On alates, the wings are located at the mesothorax and metathorax, which is consistent with all four-winged insects. The mesothorax and metathorax have well-developed exoskeletal plates; the prothorax has smaller plates.

Termites have a ten-segmented abdomen with two plates, the tergites and the sternites. The tenth abdominal segment has a pair of short cerci. There are ten tergites, of which nine are wide and one is elongated. The reproductive organs are similar to those in cockroaches but are more simplified. For example, the intromittent organ is not present in male alates, and the sperm is either immotile or aflagellate. However, Mastotermitidae termites have multiflagellate sperm with limited motility. The genitals in females are also simplified. Unlike in other termites, Mastotermitidae females have an ovipositor, a feature strikingly similar to that in female cockroaches.

The non-reproductive castes of termites are wingless and rely exclusively on their six legs for locomotion. The alates fly only for a brief amount of time, so they also rely on their legs. The appearance of the legs is similar in each caste, but the soldiers have larger and heavier legs. The structure of the legs is consistent with other insects: the parts of a leg include a coxa, trochanter, femur, tibia and the tarsus. The number of tibial spurs on an individual's leg varies. Some species of termite have an arolium, located between the claws, which is present in species that climb on smooth surfaces but is absent in most termites.

Unlike in ants, the hind-wings and fore-wings are of equal length. Most of the time, the alates are poor flyers; their technique is to launch themselves in the air and fly in a random direction. Studies show that in comparison to larger termites, smaller termites cannot fly long distances. When a termite is in flight, its wings remain at a right angle, and when the termite is at rest, its wings remain parallel to the body.

Caste system

A – King

B – Queen

C – Secondary queen

D – Tertiary queen

E – Soldiers

F – Worker

Worker termites undertake the most labour within the colony, being responsible for foraging, food storage, and brood and nest maintenance. Workers are tasked with the digestion of cellulose in food and are thus the most likely caste to be found in infested wood. The process of worker termites feeding other nestmates is known as trophallaxis. Trophallaxis is an effective nutritional tactic to convert and recycle nitrogenous components. It frees the parents from feeding all but the first generation of offspring, allowing for the group to grow much larger and ensuring that the necessary gut symbionts are transferred from one generation to another. Some termite species may rely on nymphs to perform work without differentiating as a separate caste. Workers may be male or female and are usually sterile, especially in termites that have a nest site that is separate from their foraging site. Sterile workers are sometimes termed as true workers while those that are fertile, as in the wood-nesting Archotermopsidae, are termed as false workers.

The soldier caste has anatomical and behavioural specialisations, and their sole purpose is to defend the colony. Many soldiers have large heads with highly modified powerful jaws so enlarged they cannot feed themselves. Instead, like juveniles, they are fed by workers. Fontanelles, simple holes in the forehead that exude defensive secretions, are a feature of the family Rhinotermitidae. Many species are readily identified using the characteristics of the soldiers' larger and darker head and large mandibles. Among certain termites, soldiers may use their globular (phragmotic) heads to block their narrow tunnels. Different sorts of soldiers include minor and major soldiers, and nasutes, which have a horn-like nozzle frontal projection (a nasus). These unique soldiers are able to spray noxious, sticky secretions containing diterpenes at their enemies. Nitrogen fixation plays an important role in nasute nutrition. Soldiers are usually sterile but some species of Archotermopsidae are known to have neotenic forms with soldier-like heads while also having sexual organs.

The reproductive caste of a mature colony includes a fertile female and male, known as the queen and king. The queen of the colony is responsible for egg production for the colony. Unlike in ants, the king mates with her for life. In some species, the abdomen of the queen swells up dramatically to increase fecundity, a characteristic known as physogastrism. Depending on the species, the queen starts producing reproductive winged alates at a certain time of the year, and huge swarms emerge from the colony when nuptial flight begins. These swarms attract a wide variety of predators.

Life cycle

Termites are often compared with the social Hymenoptera (ants and various species of bees and wasps), but their differing evolutionary origins result in major differences in life cycle. In the eusocial Hymenoptera, the workers are exclusively female. Males (drones) are haploid and develop from unfertilised eggs, while females (both workers and the queen) are diploid and develop from fertilised eggs. In contrast, worker termites, which constitute the majority in a colony, are diploid individuals of both sexes and develop from fertilised eggs. Depending on species, male and female workers may have different roles in a termite colony.

The life cycle of a termite begins with an egg, but is different from that of a bee or ant in that it goes through a developmental process called incomplete metamorphosis, with egg, nymph and adult stages. Nymphs resemble small adults, and go through a series of moults as they grow. In some species, eggs go through four moulting stages and nymphs go through three. Nymphs first moult into workers, and then some workers go through further moulting and become soldiers or alates; workers become alates only by moulting into alate nymphs.

The development of nymphs into adults can take months; the time period depends on food availability, temperature, and the general population of the colony. Since nymphs are unable to feed themselves, workers must feed them, but workers also take part in the social life of the colony and have certain other tasks to accomplish such as foraging, building or maintaining the nest or tending to the queen. Pheromones regulate the caste system in termite colonies, preventing all but a very few of the termites from becoming fertile queens.

Queens of the eusocial termite Reticulitermes speratus are capable of a long lifespan without sacrificing fecundity. These long-lived queens have a significantly lower level of oxidative damage, including oxidative DNA damage, than workers, soldiers and nymphs. The lower levels of damage appear to be due to increased catalase, an enzyme that protects against oxidative stress.

Reproduction

Termite alates only leave the colony when a nuptial flight takes place. Alate males and females pair up together and then land in search of a suitable place for a colony. A termite king and queen do not mate until they find such a spot. When they do, they excavate a chamber big enough for both, close up the entrance and proceed to mate. After mating, the pair never go outside and spend the rest of their lives in the nest. Nuptial flight time varies in each species. For example, alates in certain species emerge during the day in summer while others emerge during the winter. The nuptial flight may also begin at dusk, when the alates swarm around areas with many lights. The time when nuptial flight begins depends on the environmental conditions, the time of day, moisture, wind speed and precipitation. The number of termites in a colony also varies, with the larger species typically having 100–1,000 individuals. However, some termite colonies, including those with many individuals, can number in the millions.

The queen only lays 10–20 eggs in the very early stages of the colony, but lays as many as 1,000 a day when the colony is several years old. At maturity, a primary queen has a great capacity to lay eggs. In some species, the mature queen has a greatly distended abdomen and may produce 40,000 eggs a day. The two mature ovaries may have some 2,000 ovarioles each. The abdomen increases the queen's body length to several times more than before mating and reduces her ability to move freely; attendant workers provide assistance.

The king grows only slightly larger after initial mating and continues to mate with the queen for life (a termite queen can live between 30 to 50 years); this is very different from ant colonies, in which a queen mates once with the males and stores the gametes for life, as the male ants die shortly after mating. If a queen is absent, a termite king produces pheromones which encourage the development of replacement termite queens. As the queen and king are monogamous, sperm competition does not occur.

Termites going through incomplete metamorphosis on the path to becoming alates form a subcaste in certain species of termite, functioning as potential supplementary reproductives. These supplementary reproductives only mature into primary reproductives upon the death of a king or queen, or when the primary reproductives are separated from the colony. Supplementaries have the ability to replace a dead primary reproductive, and there may also be more than a single supplementary within a colony. Some queens have the ability to switch from sexual reproduction to asexual reproduction. Studies show that while termite queens mate with the king to produce colony workers, the queens reproduce their replacements (neotenic queens) parthenogenetically.

The neotropical termite Embiratermes neotenicus and several other related species produce colonies that contain a primary king accompanied by a primary queen or by up to 200 neotenic queens that had originated through thelytokous parthenogenesis of a founding primary queen. The form of parthenogenesis likely employed maintains heterozygosity in the passage of the genome from mother to daughter, thus avoiding inbreeding depression.

Behaviour and ecology

Diet

Termites are detritivores, consuming dead plants at any level of decomposition. They also play a vital role in the ecosystem by recycling waste material such as dead wood, faeces and plants. Many species eat cellulose, having a specialised midgut that breaks down the fibre. Termites are considered to be a major source (11%) of atmospheric methane, one of the prime greenhouse gases, produced from the breakdown of cellulose. Termites rely primarily upon symbiotic protozoa (metamonads) and other microbes such as flagellate protists in their guts to digest the cellulose for them, allowing them to absorb the end products for their own use. The microbial ecosystem present in the termite gut contains many species found nowhere else on Earth. Termites hatch without these symbionts present in their guts, and develop them after fed a culture from other termites. Gut protozoa, such as Trichonympha, in turn, rely on symbiotic bacteria embedded on their surfaces to produce some of the necessary digestive enzymes. Most higher termites, especially in the family Termitidae, can produce their own cellulase enzymes, but they rely primarily upon the bacteria. The flagellates have been lost in Termitidae. Researches have found species of spirochetes living in termite guts capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen to a form usable by the insect. Scientists' understanding of the relationship between the termite digestive tract and the microbial endosymbionts is still rudimentary; what is true in all termite species, however, is that the workers feed the other members of the colony with substances derived from the digestion of plant material, either from the mouth or anus. Judging from closely related bacterial species, it is strongly presumed that the termites' and cockroach's gut microbiota derives from their dictyopteran ancestors.

Certain species such as Gnathamitermes tubiformans have seasonal food habits. For example, they may preferentially consume Red three-awn (Aristida longiseta) during the summer, Buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides) from May to August, and blue grama Bouteloua gracilis during spring, summer and autumn. Colonies of G. tubiformans consume less food in spring than they do during autumn when their feeding activity is high.

Various woods differ in their susceptibility to termite attack; the differences are attributed to such factors as moisture content, hardness, and resin and lignin content. In one study, the drywood termite Cryptotermes brevis strongly preferred poplar and maple woods to other woods that were generally rejected by the termite colony. These preferences may in part have represented conditioned or learned behaviour.

Some species of termite practice fungiculture. They maintain a "garden" of specialised fungi of genus Termitomyces, which are nourished by the excrement of the insects. When the fungi are eaten, their spores pass undamaged through the intestines of the termites to complete the cycle by germinating in the fresh faecal pellets. Molecular evidence suggests that the family Macrotermitinae developed agriculture about 31 million years ago. It is assumed that more than 90 percent of dry wood in the semiarid savannah ecosystems of Africa and Asia are reprocessed by these termites. Originally living in the rainforest, fungus farming allowed them to colonise the African savannah and other new environments, eventually expanding into Asia.

Depending on their feeding habits, termites are placed into two groups: the lower termites and higher termites. The lower termites predominately feed on wood. As wood is difficult to digest, termites prefer to consume fungus-infected wood because it is easier to digest and the fungi are high in protein. Meanwhile, the higher termites consume a wide variety of materials, including faeces, humus, grass, leaves and roots. The gut in the lower termites contains many species of bacteria along with protozoa, while the higher termites only have a few species of bacteria with no protozoa.

Predators

Termites are consumed by a wide variety of predators. One termite species alone, Hodotermes mossambicus, was found in the stomach contents of 65 birds and 19 mammals. Arthropods such as ants, centipedes, cockroaches, crickets, dragonflies, scorpions and spiders, reptiles such as lizards, and amphibians such as frogs and toads consume termites, with two spiders in the family Ammoxenidae being specialist termite predators. Other predators include aardvarks, aardwolves, anteaters, bats, bears, bilbies, many birds, echidnas, foxes, galagos, numbats, mice and pangolins. The aardwolf is an insectivorous mammal that primarily feeds on termites; it locates its food by sound and also by detecting the scent secreted by the soldiers; a single aardwolf is capable of consuming thousands of termites in a single night by using its long, sticky tongue. Sloth bears break open mounds to consume the nestmates, while chimpanzees have developed tools to "fish" termites from their nest. Wear pattern analysis of bone tools used by the early hominin Paranthropus robustus suggests that they used these tools to dig into termite mounds.

Among all predators, ants are the greatest enemy to termites. Some ant genera are specialist predators of termites. For example, Megaponera is a strictly termite-eating (termitophagous) genus that perform raiding activities, some lasting several hours. Paltothyreus tarsatus is another termite-raiding species, with each individual stacking as many termites as possible in its mandibles before returning home, all the while recruiting additional nestmates to the raiding site through chemical trails. The Malaysian basicerotine ants Eurhopalothrix heliscata uses a different strategy of termite hunting by pressing themselves into tight spaces, as they hunt through rotting wood housing termite colonies. Once inside, the ants seize their prey by using their short but sharp mandibles. Tetramorium uelense is a specialised predator species that feeds on small termites. A scout recruits 10–30 workers to an area where termites are present, killing them by immobilising them with their stinger. Centromyrmex and Iridomyrmex colonies sometimes nest in termite mounds, and so the termites are preyed on by these ants. No evidence for any kind of relationship (other than a predatory one) is known. Other ants, including Acanthostichus, Camponotus, Crematogaster, Cylindromyrmex, Leptogenys, Odontomachus, Ophthalmopone, Pachycondyla, Rhytidoponera, Solenopsis and Wasmannia, also prey on termites. In contrast to all these ant species, and despite their enormous diversity of prey, Dorylus ants rarely consume termites.

Ants are not the only invertebrates that perform raids. Many sphecoid wasps and several species including Polybia and Angiopolybia are known to raid termite mounds during the termites' nuptial flight.

Parasites, pathogens and viruses

Termites are less likely to be attacked by parasites than bees, wasps and ants, as they are usually well protected in their mounds. Nevertheless, termites are infected by a variety of parasites. Some of these include dipteran flies, Pyemotes mites, and a large number of nematode parasites. Most nematode parasites are in the order Rhabditida; others are in the genus Mermis, Diplogaster aerivora and Harteria gallinarum. Under imminent threat of an attack by parasites, a colony may migrate to a new location. Certain fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus nomius and Metarhizium anisopliae are, however, major threats to a termite colony as they are not host-specific and may infect large portions of the colony; transmission usually occurs via direct physical contact. M. anisopliae is known to weaken the termite immune system. Infection with A. nomius only occurs when a colony is under great stress. Over 34 fungal species are known to live as parasites on the exoskeleton of termites, with many being host-specific and only causing indirect harm to their host.

Termites are infected by viruses including Entomopoxvirinae and the Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus.

Locomotion and foraging

Because the worker and soldier castes lack wings and thus never fly, and the reproductives use their wings for just a brief amount of time, termites predominantly rely upon their legs to move about.

Foraging behaviour depends on the type of termite. For example, certain species feed on the wood structures they inhabit, and others harvest food that is near the nest. Most workers are rarely found out in the open, and do not forage unprotected; they rely on sheeting and runways to protect them from predators. Subterranean termites construct tunnels and galleries to look for food, and workers who manage to find food sources recruit additional nestmates by depositing a phagostimulant pheromone that attracts workers. Foraging workers use semiochemicals to communicate with each other, and workers who begin to forage outside of their nest release trail pheromones from their sternal glands. In one species, Nasutitermes costalis, there are three phases in a foraging expedition: first, soldiers scout an area. When they find a food source, they communicate to other soldiers and a small force of workers starts to emerge. In the second phase, workers appear in large numbers at the site. The third phase is marked by a decrease in the number of soldiers present and an increase in the number of workers. Isolated termite workers may engage in Lévy flight behaviour as an optimised strategy for finding their nestmates or foraging for food.

Competition

Competition between two colonies always results in agonistic behaviour towards each other, resulting in fights. These fights can cause mortality on both sides and, in some cases, the gain or loss of territory. "Cemetery pits" may be present, where the bodies of dead termites are buried.

Studies show that when termites encounter each other in foraging areas, some of the termites deliberately block passages to prevent other termites from entering. Dead termites from other colonies found in exploratory tunnels leads to the isolation of the area and thus the need to construct new tunnels. Conflict between two competitors does not always occur. For example, though they might block each other's passages, colonies of Macrotermes bellicosus and Macrotermes subhyalinus are not always aggressive towards each other. Suicide cramming is known in Coptotermes formosanus. Since C. formosanus colonies may get into physical conflict, some termites squeeze tightly into foraging tunnels and die, successfully blocking the tunnel and ending all agonistic activities.

Among the reproductive caste, neotenic queens may compete with each other to become the dominant queen when there are no primary reproductives. This struggle among the queens leads to the elimination of all but a single queen, which, with the king, takes over the colony.

Ants and termites may compete with each other for nesting space. In particular, ants that prey on termites usually have a negative impact on arboreal nesting species.

Communication

Most termites are blind, so communication primarily occurs through chemical, mechanical and pheromonal cues. These methods of communication are used in a variety of activities, including foraging, locating reproductives, construction of nests, recognition of nestmates, nuptial flight, locating and fighting enemies, and defending the nests. The most common way of communicating is through antennation. A number of pheromones are known, including contact pheromones (which are transmitted when workers are engaged in trophallaxis or grooming) and alarm, trail and sex pheromones. The alarm pheromone and other defensive chemicals are secreted from the frontal gland. Trail pheromones are secreted from the sternal gland, and sex pheromones derive from two glandular sources: the sternal and tergal glands. When termites go out to look for food, they forage in columns along the ground through vegetation. A trail can be identified by the faecal deposits or runways that are covered by objects. Workers leave pheromones on these trails, which are detected by other nestmates through olfactory receptors. Termites can also communicate through mechanical cues, vibrations, and physical contact. These signals are frequently used for alarm communication or for evaluating a food source.

When termites construct their nests, they use predominantly indirect communication. No single termite would be in charge of any particular construction project. Individual termites react rather than think, but at a group level, they exhibit a sort of collective cognition. Specific structures or other objects such as pellets of soil or pillars cause termites to start building. The termite adds these objects onto existing structures, and such behaviour encourages building behaviour in other workers. The result is a self-organised process whereby the information that directs termite activity results from changes in the environment rather than from direct contact among individuals.

Termites can distinguish nestmates and non-nestmates through chemical communication and gut symbionts: chemicals consisting of hydrocarbons released from the cuticle allow the recognition of alien termite species. Each colony has its own distinct odour. This odour is a result of genetic and environmental factors such as the termites' diet and the composition of the bacteria within the termites' intestines.

Defence

Termites rely on alarm communication to defend a colony. Alarm pheromones can be released when the nest has been breached or is being attacked by enemies or potential pathogens. Termites always avoid nestmates infected with Metarhizium anisopliae spores, through vibrational signals released by infected nestmates. Other methods of defence include intense jerking and secretion of fluids from the frontal gland and defecating faeces containing alarm pheromones.

In some species, some soldiers block tunnels to prevent their enemies from entering the nest, and they may deliberately rupture themselves as an act of defence. In cases where the intrusion is coming from a breach that is larger than the soldier's head, soldiers form a phalanx-like formation around the breach and bite at intruders. If an invasion carried out by Megaponera analis is successful, an entire colony may be destroyed, although this scenario is rare.

To termites, any breach of their tunnels or nests is a cause for alarm. When termites detect a potential breach, the soldiers usually bang their heads, apparently to attract other soldiers for defence and to recruit additional workers to repair any breach. Additionally, an alarmed termite bumps into other termites which causes them to be alarmed and to leave pheromone trails to the disturbed area, which is also a way to recruit extra workers.

The pantropical subfamily Nasutitermitinae has a specialised caste of soldiers, known as nasutes, that have the ability to exude noxious liquids through a horn-like frontal projection that they use for defence. Nasutes have lost their mandibles through the course of evolution and must be fed by workers. A wide variety of monoterpene hydrocarbon solvents have been identified in the liquids that nasutes secrete. Similarly, Formosan subterranean termites have been known to secrete naphthalene to protect their nests.

Soldiers of the species Globitermes sulphureus commit suicide by autothysis – rupturing a large gland just beneath the surface of their cuticles. The thick, yellow fluid in the gland becomes very sticky on contact with the air, entangling ants or other insects that are trying to invade the nest. Another termite, Neocapriterme taracua, also engages in suicidal defence. Workers physically unable to use their mandibles while in a fight form a pouch full of chemicals, then deliberately rupture themselves, releasing toxic chemicals that paralyse and kill their enemies. The soldiers of the neotropical termite family Serritermitidae have a defence strategy which involves front gland autothysis, with the body rupturing between the head and abdomen. When soldiers guarding nest entrances are attacked by intruders, they engage in autothysis, creating a block that denies entry to any attacker.

Workers use several different strategies to deal with their dead, including burying, cannibalism, and avoiding a corpse altogether. To avoid pathogens, termites occasionally engage in necrophoresis, in which a nestmate carries away a corpse from the colony to dispose of it elsewhere. Which strategy is used depends on the nature of the corpse a worker is dealing with (i.e. the age of the carcass).

Relationship with other organisms

A species of fungus is known to mimic termite eggs, successfully avoiding its natural predators. These small brown balls, known as "termite balls", rarely kill the eggs, and in some cases the workers tend to them. This fungus mimics these eggs by producing a cellulose-digesting enzyme known as glucosidases. A unique mimicking behaviour exists between various species of Trichopsenius beetles and certain termite species within Reticulitermes. The beetles share the same cuticle hydrocarbons as the termites and even biosynthesize them. This chemical mimicry allows the beetles to integrate themselves within the termite colonies. The developed appendages on the physogastric abdomen of Austrospirachtha mimetes allows the beetle to mimic a termite worker.

Some species of ant are known to capture termites to use as a fresh food source later on, rather than killing them. For example, Formica nigra captures termites, and those who try to escape are immediately seized and driven underground. Certain species of ants in the subfamily Ponerinae conduct these raids although other ant species go in alone to steal the eggs or nymphs. Ants such as Megaponera analis attack the outside of mounds and Dorylinae ants attack underground. Despite this, some termites and ants can coexist peacefully. Some species of termite, including Nasutitermes corniger, form associations with certain ant species to keep away predatory ant species. The earliest known association between Azteca ants and Nasutitermes termites date back to the Oligocene to Miocene period.

54 species of ants are known to inhabit Nasutitermes mounds, both occupied and abandoned ones. One reason many ants live in Nasutitermes mounds is due to the termites' frequent occurrence in their geographical range; another is to protect themselves from floods. Iridomyrmex also inhabits termite mounds although no evidence for any kind of relationship (other than a predatory one) is known. In rare cases, certain species of termites live inside active ant colonies. Some invertebrate organisms such as beetles, caterpillars, flies and millipedes are termitophiles and dwell inside termite colonies (they are unable to survive independently). As a result, certain beetles and flies have evolved with their hosts. They have developed a gland that secrete a substance that attracts the workers by licking them. Mounds may also provide shelter and warmth to birds, lizards, snakes and scorpions.

Termites are known to carry pollen and regularly visit flowers, so are regarded as potential pollinators for a number of flowering plants. One flower in particular, Rhizanthella gardneri, is regularly pollinated by foraging workers, and it is perhaps the only Orchidaceae flower in the world to be pollinated by termites.

Many plants have developed effective defences against termites. However, seedlings are vulnerable to termite attacks and need additional protection, as their defence mechanisms only develop when they have passed the seedling stage. Defence is typically achieved by secreting antifeedant chemicals into the woody cell walls. This reduces the ability of termites to efficiently digest the cellulose. A commercial product, "Blockaid", has been developed in Australia that uses a range of plant extracts to create a paint-on nontoxic termite barrier for buildings. An extract of a species of Australian figwort, Eremophila, has been shown to repel termites; tests have shown that termites are strongly repelled by the toxic material to the extent that they will starve rather than consume the food. When kept close to the extract, they become disoriented and eventually die.

Relationship with the environment

Termite populations can be substantially impacted by environmental changes including those caused by human intervention. A Brazilian study investigated the termite assemblages of three sites of Caatinga under different levels of anthropogenic disturbance in the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil were sampled using 65 x 2 m transects. A total of 26 species of termites were present in the three sites, and 196 encounters were recorded in the transects. The termite assemblages were considerably different among sites, with a conspicuous reduction in both diversity and abundance with increased disturbance, related to the reduction of tree density and soil cover, and with the intensity of trampling by cattle and goats. The wood-feeders were the most severely affected feeding group.

Nests

A termite nest can be considered as being composed of two parts, the inanimate and the animate. The animate is all of the termites living inside the colony, and the inanimate part is the structure itself, which is constructed by the termites. Nests can be broadly separated into three main categories: subterranean (completely below ground), epigeal (protruding above the soil surface), and arboreal (built above ground, but always connected to the ground via shelter tubes). Epigeal nests (mounds) protrude from the earth with ground contact and are made out of earth and mud. A nest has many functions such as providing a protected living space and providing shelter against predators. Most termites construct underground colonies rather than multifunctional nests and mounds. Primitive termites of today nest in wooden structures such as logs, stumps and the dead parts of trees, as did termites millions of years ago.

To build their nests, termites primarily use faeces, which have many desirable properties as a construction material. Other building materials include partly digested plant material, used in carton nests (arboreal nests built from faecal elements and wood), and soil, used in subterranean nest and mound construction. Not all nests are visible, as many nests in tropical forests are located underground. Species in the subfamily Apicotermitinae are good examples of subterranean nest builders, as they only dwell inside tunnels. Other termites live in wood, and tunnels are constructed as they feed on the wood. Nests and mounds protect the termites' soft bodies against desiccation, light, pathogens and parasites, as well as providing a fortification against predators. Nests made out of carton are particularly weak, and so the inhabitants use counter-attack strategies against invading predators.

Arboreal carton nests of mangrove swamp-dwelling Nasutitermes are enriched in lignin and depleted in cellulose and xylans. This change is caused by bacterial decay in the gut of the termites: they use their faeces as a carton building material. Arboreal termites nests can account for as much as 2% of above ground carbon storage in Puerto Rican mangrove swamps. These Nasutitermes nests are mainly composed of partially biodegraded wood material from the stems and branches of mangrove trees, namely, Rhizophora mangle (red mangrove), Avicennia germinans (black mangrove) and Laguncularia racemose (white mangrove).

Some species build complex nests called polycalic nests; this habitat is called polycalism. Polycalic species of termites form multiple nests, or calies, connected by subterranean chambers. The termite genera Apicotermes and Trinervitermes are known to have polycalic species. Polycalic nests appear to be less frequent in mound-building species although polycalic arboreal nests have been observed in a few species of Nasutitermes.

Mounds

Nests are considered mounds if they protrude from the earth's surface. A mound provides termites the same protection as a nest but is stronger. Mounds located in areas with torrential and continuous rainfall are at risk of mound erosion due to their clay-rich construction. Those made from carton can provide protection from the rain, and in fact can withstand high precipitation. Certain areas in mounds are used as strong points in case of a breach. For example, Cubitermes colonies build narrow tunnels used as strong points, as the diameter of the tunnels is small enough for soldiers to block. A highly protected chamber, known as the "queens cell", houses the queen and king and is used as a last line of defence.

Species in the genus Macrotermes arguably build the most complex structures in the insect world, constructing enormous mounds. These mounds are among the largest in the world, reaching a height of 8 to 9 metres (26 to 29 feet), and consist of chimneys, pinnacles and ridges. Another termite species, Amitermes meridionalis, can build nests 3 to 4 metres (9 to 13 feet) high and 2.5 metres (8 feet) wide. The tallest mound ever recorded was 12.8 metres (42 ft) long found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The sculptured mounds sometimes have elaborate and distinctive forms, such as those of the compass termite (Amitermes meridionalis and A. laurensis), which builds tall, wedge-shaped mounds with the long axis oriented approximately north–south, which gives them their common name. This orientation has been experimentally shown to assist thermoregulation. The north–south orientation causes the internal temperature of a mound to increase rapidly during the morning while avoiding overheating from the midday sun. The temperature then remains at a plateau for the rest of the day until the evening.

Cathedral mounds in the Northern Territory, Australia

Termite mound in Queensland, Australia

Termites in a mound, Analamazoatra Reserve, Madagascar

Termite mound in Namibia

Shelter tubes

Termites construct shelter tubes, also known as earthen tubes or mud tubes, that start from the ground. These shelter tubes can be found on walls and other structures. Constructed by termites during the night, a time of higher humidity, these tubes provide protection to termites from potential predators, especially ants. Shelter tubes also provide high humidity and darkness and allow workers to collect food sources that cannot be accessed in any other way. These passageways are made from soil and faeces and are normally brown in colour. The size of these shelter tubes depends on the number of food sources that are available. They range from less than 1 cm to several cm in width, but may be dozens of metres in length.

Relationship with humans

As pests

Owing to their wood-eating habits, many termite species can do significant damage to unprotected buildings and other wooden structures. Termites play an important role as decomposers of wood and vegetative material, and the conflict with humans occurs where structures and landscapes containing structural wood components, cellulose derived structural materials and ornamental vegetation provide termites with a reliable source of food and moisture. Their habit of remaining concealed often results in their presence being undetected until the timbers are severely damaged, with only a thin exterior layer of wood remaining, which protects them from the environment. Of the 3,106 species known, only 183 species cause damage; 83 species cause significant damage to wooden structures. In North America, 18 subterranean species are pests; in Australia, 16 species have an economic impact; in the Indian subcontinent 26 species are considered pests, and in tropical Africa, 24. In Central America and the West Indies, there are 17 pest species. Among the termite genera, Coptotermes has the highest number of pest species of any genus, with 28 species known to cause damage. Less than 10% of drywood termites are pests, but they infect wooden structures and furniture in tropical, subtropical and other regions. Dampwood termites only attack lumber material exposed to rainfall or soil.

Drywood termites thrive in warm climates, and human activities can enable them to invade homes since they can be transported through contaminated goods, containers and ships. Colonies of termites have been seen thriving in warm buildings located in cold regions. Some termites are considered invasive species. Cryptotermes brevis, the most widely introduced invasive termite species in the world, has been introduced to all the islands in the West Indies and to Australia.

In addition to causing damage to buildings, termites can also damage food crops. Termites may attack trees whose resistance to damage is low but generally ignore fast-growing plants. Most attacks occur at harvest time; crops and trees are attacked during the dry season.

The damage caused by termites costs the southwestern United States approximately $1.5 billion each year in wood structure damage, but the true cost of damage worldwide cannot be determined. Drywood termites are responsible for a large proportion of the damage caused by termites. The goal of termite control is to keep structures and susceptible ornamental plants free from termites.; Structures may be homes or business, or elements such as wooden fence posts and telephone poles. Regular and thorough inspections by a trained professional may be necessary to detect termite activity in the absence of more obvious signs like termite swarmers or alates inside or adjacent to a structure. Termite monitors made of wood or cellulose adjacent to a structure may also provide indication of termite foraging activity where it will be in conflict with humans. Termites can be controlled by application of Bordeaux mixture or other substances that contain copper such as chromated copper arsenate. In the United states, application of a soil termiticide with the active ingredient Fipronil, such as Termidor SC or Taurus SC, by a licensed professional, is a common remedy approved by the Environmental Protection Agency for economically significant subterranean termites. A growing demand for alternative, green, and "more natural" extermination methods has increased demand for mechanical and biological control methods such as Orange Oil.

To better control the population of termites, various methods have been developed to track termite movements. One early method involved distributing termite bait laced with immunoglobulin G (IgG) marker proteins from rabbits or chickens. Termites collected from the field could be tested for the rabbit-IgG markers using a rabbit-IgG-specific assay. More recently developed, less expensive alternatives include tracking the termites using egg white, cow milk, or soy milk proteins, which can be sprayed on termites in the field. Termites bearing these proteins can be traced using a protein-specific ELISA test.

As food

43 termite species are used as food by humans or are fed to livestock. These insects are particularly important in impoverished countries where malnutrition is common, as the protein from termites can help improve the human diet. Termites are consumed in many regions globally, but this practice has only become popular in developed nations in recent years.

Termites are consumed by people in many different cultures around the world. In many parts of Africa, the alates are an important factor in the diets of native populations. Groups have different ways of collecting or cultivating insects; sometimes collecting soldiers from several species. Though harder to acquire, queens are regarded as a delicacy. Termite alates are high in nutrition with adequate levels of fat and protein. They are regarded as pleasant in taste, having a nut-like flavour after they are cooked.

Alates are collected when the rainy season begins. During a nuptial flight, they are typically seen around lights to which they are attracted, and so nets are set up on lamps and captured alates are later collected. The wings are removed through a technique that is similar to winnowing. The best result comes when they are lightly roasted on a hot plate or fried until crisp. Oil is not required as their bodies usually contain sufficient amounts of oil. Termites are typically eaten when livestock is lean and tribal crops have not yet developed or produced any food, or if food stocks from a previous growing season are limited.

In addition to Africa, termites are consumed in local or tribal areas in Asia and North and South America. In Australia, Indigenous Australians are aware that termites are edible but do not consume them even in times of scarcity; there are few explanations as to why. Termite mounds are the main sources of soil consumption (geophagy) in many countries including Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Researchers have suggested that termites are suitable candidates for human consumption and space agriculture, as they are high in protein and can be used to convert inedible waste to consumable products for humans.

In agriculture

Termites can be major agricultural pests, particularly in East Africa and North Asia, where crop losses can be severe (3–100% in crop loss in Africa). Counterbalancing this is the greatly improved water infiltration where termite tunnels in the soil allow rainwater to soak in deeply, which helps reduce runoff and consequent soil erosion through bioturbation. In South America, cultivated plants such as eucalyptus, upland rice and sugarcane can be severely damaged by termite infestations, with attacks on leaves, roots and woody tissue. Termites can also attack other plants, including cassava, coffee, cotton, fruit trees, maize, peanuts, soybeans and vegetables. Mounds can disrupt farming activities, making it difficult for farmers to operate farming machinery; however, despite farmers' dislike of the mounds, it is often the case that no net loss of production occurs. Termites can be beneficial to agriculture, such as by boosting crop yields and enriching the soil. Termites and ants can re-colonise untilled land that contains crop stubble, which colonies use for nourishment when they establish their nests. The presence of nests in fields enables larger amounts of rainwater to soak into the ground and increases the amount of nitrogen in the soil, both essential for the growth of crops.

In science and technology

The termite gut has inspired various research efforts aimed at replacing fossil fuels with cleaner, renewable energy sources. Termites are efficient bioreactors, capable of producing two litres of hydrogen from a single sheet of paper. Approximately 200 species of microbes live inside the termite hindgut, releasing the hydrogen that was trapped inside wood and plants that they digest. Through the action of unidentified enzymes in the termite gut, lignocellulose polymers are broken down into sugars and are transformed into hydrogen. The bacteria within the gut turns the sugar and hydrogen into cellulose acetate, an acetate ester of cellulose on which termites rely for energy. Community DNA sequencing of the microbes in the termite hindgut has been employed to provide a better understanding of the metabolic pathway. Genetic engineering may enable hydrogen to be generated in bioreactors from woody biomass.

The development of autonomous robots capable of constructing intricate structures without human assistance has been inspired by the complex mounds that termites build. These robots work independently and can move by themselves on a tracked grid, capable of climbing and lifting up bricks. Such robots may be useful for future projects on Mars, or for building levees to prevent flooding.

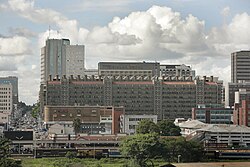

Termites use sophisticated means to control the temperatures of their mounds. As discussed above, the shape and orientation of the mounds of the Australian compass termite stabilises their internal temperatures during the day. As the towers heat up, the solar chimney effect (stack effect) creates an updraft of air within the mound. Wind blowing across the tops of the towers enhances the circulation of air through the mounds, which also include side vents in their construction. The solar chimney effect has been in use for centuries in the Middle East and Near East for passive cooling, as well as in Europe by the Romans. It is only relatively recently, however, that climate responsive construction techniques have become incorporated into modern architecture. Especially in Africa, the stack effect has become a popular means to achieve natural ventilation and passive cooling in modern buildings.

In culture

The Eastgate Centre is a shopping centre and office block in central Harare, Zimbabwe, whose architect, Mick Pearce, used passive cooling inspired by that used by the local termites. It was the first major building exploiting termite-inspired cooling techniques to attract international attention. Other such buildings include the Learning Resource Center at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa and the Council House 2 building in Melbourne, Australia.

Few zoos hold termites, due to the difficulty in keeping them captive and to the reluctance of authorities to permit potential pests. One of the few that do, the Zoo Basel in Switzerland, has two thriving Macrotermes bellicosus populations – resulting in an event very rare in captivity: the mass migrations of young flying termites. This happened in September 2008, when thousands of male termites left their mound each night, died, and covered the floors and water pits of the house holding their exhibit.

African tribes in several countries have termites as totems, and for this reason tribe members are forbidden to eat the reproductive alates. Termites are widely used in traditional popular medicine; they are used as treatments for diseases and other conditions such as asthma, bronchitis, hoarseness, influenza, sinusitis, tonsillitis and whooping cough. In Nigeria, Macrotermes nigeriensis is used for spiritual protection and to treat wounds and sick pregnant women. In Southeast Asia, termites are used in ritual practices. In Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand, termite mounds are commonly worshiped among the populace. Abandoned mounds are viewed as structures created by spirits, believing a local guardian dwells within the mound; this is known as Keramat and Datok Kong. In urban areas, local residents construct red-painted shrines over mounds that have been abandoned, where they pray for good health, protection and luck.