In biology, epigenetics is the study of heritable phenotype changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix epi- (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in epigenetics implies features that are "on top of" or "in addition to" the traditional genetic basis for inheritance. Epigenetics most often involves changes that affect gene activity and expression, but the term can also be used to describe any heritable phenotypic change. Such effects on cellular and physiological phenotypic traits may result from external or environmental factors, or be part of normal development.

The term also refers to the changes themselves: functionally relevant changes to the genome that do not involve a change in the nucleotide sequence. Examples of mechanisms that produce such changes are DNA methylation and histone modification, each of which alters how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Gene expression can be controlled through the action of repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA. These epigenetic changes may last through cell divisions for the duration of the cell's life, and may also last for multiple generations, even though they do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism; instead, non-genetic factors cause the organism's genes to behave (or "express themselves") differently.

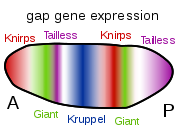

One example of an epigenetic change in eukaryotic biology is the process of cellular differentiation. During morphogenesis, totipotent stem cells become the various pluripotent cell lines of the embryo, which in turn become fully differentiated cells. In other words, as a single fertilized egg cell – the zygote – continues to divide, the resulting daughter cells change into all the different cell types in an organism, including neurons, muscle cells, epithelium, endothelium of blood vessels, etc., by activating some genes while inhibiting the expression of others.

Definitions

The term epigenetics in its contemporary usage emerged in the 1990s, but for some years has been used with somewhat variable meanings. A definition of the concept of epigenetic trait as a "stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence" was formulated at a Cold Spring Harbor meeting in 2008, although alternate definitions that include non-heritable traits are still being used widely.

The term epigenesis has a generic meaning of "extra growth", and has been used in English since the 17th century.

Waddington's canalisation, 1940s

The hypothesis of epigenetic changes affecting the expression of chromosomes was put forth by the Russian biologist Nikolai Koltsov. From the generic meaning, and the associated adjective epigenetic, British embryologist C. H. Waddington coined the term epigenetics in 1942 as pertaining to epigenesis, in parallel to Valentin Haecker's 'phenogenetics' (Phänogenetik). Epigenesis in the context of the biology of that period referred to the differentiation of cells from their initial totipotent state during embryonic development.

When Waddington coined the term, the physical nature of genes and their role in heredity was not known. He used it instead as a conceptual model of how genetic components might interact with their surroundings to produce a phenotype; he used the phrase "epigenetic landscape" as a metaphor for biological development. Waddington held that cell fates were established during development in a process he called canalisation much as a marble rolls down to the point of lowest local elevation. Waddington suggested visualising increasing irreversibility of cell type differentiation as ridges rising between the valleys where the marbles (analogous to cells) are travelling.

In recent times, Waddington's notion of the epigenetic landscape has been rigorously formalized in the context of the systems dynamics state approach to the study of cell-fate. Cell-fate determination is predicted to exhibit certain dynamics, such as attractor-convergence (the attractor can be an equilibrium point, limit cycle or strange attractor) or oscillatory.

Contemporary

Robin Holliday defined in 1990 epigenetics as "the study of the mechanisms of temporal and spatial control of gene activity during the development of complex organisms." Thus, in its broadest sense, epigenetic can be used to describe anything other than DNA sequence that influences the development of an organism.

More recent usage of the word in biology follows stricter definitions. It is, as defined by Arthur Riggs and colleagues, "the study of mitotically and/or meiotically heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence."

The term has also been used, however, to describe processes which have not been demonstrated to be heritable, such as some forms of histone modification; there are therefore attempts to redefine "epigenetics" in broader terms that would avoid the constraints of requiring heritability. For example, Adrian Bird defined epigenetics as "the structural adaptation of chromosomal regions so as to register, signal or perpetuate altered activity states." This definition would be inclusive of transient modifications associated with DNA repair or cell-cycle phases as well as stable changes maintained across multiple cell generations, but exclude others such as templating of membrane architecture and prions unless they impinge on chromosome function. Such redefinitions however are not universally accepted and are still subject to debate. The NIH "Roadmap Epigenomics Project", ongoing as of 2016, uses the following definition: "For purposes of this program, epigenetics refers to both heritable changes in gene activity and expression (in the progeny of cells or of individuals) and also stable, long-term alterations in the transcriptional potential of a cell that are not necessarily heritable." In 2008, a consensus definition of the epigenetic trait, a "stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence", was made at a Cold Spring Harbor meeting.

The similarity of the word to "genetics" has generated many parallel usages. The "epigenome" is a parallel to the word "genome", referring to the overall epigenetic state of a cell, and epigenomics refers to global analyses of epigenetic changes across the entire genome. The phrase "genetic code" has also been adapted – the "epigenetic code" has been used to describe the set of epigenetic features that create different phenotypes in different cells from the same underlying DNA sequence. Taken to its extreme, the "epigenetic code" could represent the total state of the cell, with the position of each molecule accounted for in an epigenomic map, a diagrammatic representation of the gene expression, DNA methylation and histone modification status of a particular genomic region. More typically, the term is used in reference to systematic efforts to measure specific, relevant forms of epigenetic information such as the histone code or DNA methylation patterns.

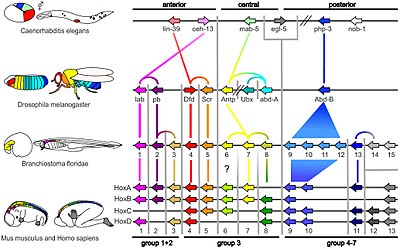

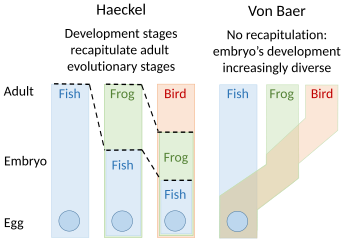

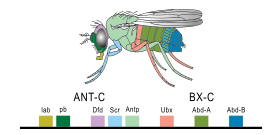

Developmental psychology

In a sense somewhat unrelated to its use in any biological disciplines, the term "epigenetic" has also been used in developmental psychology to describe psychological development as the result of an ongoing, bi-directional interchange between heredity and the environment. Interactive ideas of development have been discussed in various forms and under various names throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. An early version was proposed, among the founding statements in embryology, by Karl Ernst von Baer and popularized by Ernst Haeckel. A radical epigenetic view (physiological epigenesis) was developed by Paul Wintrebert. Another variation, probabilistic epigenesis, was presented by Gilbert Gottlieb in 2003. This view encompasses all of the possible developing factors on an organism and how they not only influence the organism and each other but how the organism also influences its own development. Like wise, the long-standing notion "cells that fire together, wire together" derives from Hebbian theory which asserts that synaptogenesis, a developmental process with great epigenetic precedence, depends on the activity of the respective synapses within a neural network. Where experience alters the excitability of neurons, increased neural activity has been linked to increased demethylation .

The developmental psychologist Erik Erikson wrote of an epigenetic principle in his 1968 book Identity: Youth and Crisis, encompassing the notion that we develop through an unfolding of our personality in predetermined stages, and that our environment and surrounding culture influence how we progress through these stages. This biological unfolding in relation to our socio-cultural settings is done in stages of psychosocial development, where "progress through each stage is in part determined by our success, or lack of success, in all the previous stages."

Although empirical studies have yielded discrepant results, epigenetic modifications are thought to be a biological mechanism for transgenerational trauma.

Molecular basis

Epigenetic changes modify the activation of certain genes, but not the genetic code sequence of DNA. The microstructure (not code) of DNA itself or the associated chromatin proteins may be modified, causing activation or silencing. This mechanism enables differentiated cells in a multicellular organism to express only the genes that are necessary for their own activity. Epigenetic changes are preserved when cells divide. Most epigenetic changes only occur within the course of one individual organism's lifetime; however, these epigenetic changes can be transmitted to the organism's offspring through a process called transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Moreover, if gene inactivation occurs in a sperm or egg cell that results in fertilization, this epigenetic modification may also be transferred to the next generation.

Specific epigenetic processes include paramutation, bookmarking, imprinting, gene silencing, X chromosome inactivation, position effect, DNA methylation reprogramming, transvection, maternal effects, the progress of carcinogenesis, many effects of teratogens, regulation of histone modifications and heterochromatin, and technical limitations affecting parthenogenesis and cloning.

DNA damage

DNA damage can also cause epigenetic changes. DNA damage is very frequent, occurring on average about 60,000 times a day per cell of the human body (see DNA damage (naturally occurring)). These damages are largely repaired, but at the site of a DNA repair, epigenetic changes can remain. In particular, a double strand break in DNA can initiate unprogrammed epigenetic gene silencing both by causing DNA methylation as well as by promoting silencing types of histone modifications (chromatin remodeling - see next section). In addition, the enzyme Parp1 (poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase) and its product poly(ADP)-ribose (PAR) accumulate at sites of DNA damage as part of a repair process. This accumulation, in turn, directs recruitment and activation of the chromatin remodeling protein ALC1 that can cause nucleosome remodeling. Nucleosome remodeling has been found to cause, for instance, epigenetic silencing of DNA repair gene MLH1. DNA damaging chemicals, such as benzene, hydroquinone, styrene, carbon tetrachloride and trichloroethylene, cause considerable hypomethylation of DNA, some through the activation of oxidative stress pathways.

Foods are known to alter the epigenetics of rats on different diets. Some food components epigenetically increase the levels of DNA repair enzymes such as MGMT and MLH1 and p53. Other food components can reduce DNA damage, such as soy isoflavones. In one study, markers for oxidative stress, such as modified nucleotides that can result from DNA damage, were decreased by a 3-week diet supplemented with soy. A decrease in oxidative DNA damage was also observed 2 h after consumption of anthocyanin-rich bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillius L.) pomace extract.

Techniques used to study epigenetics

Epigenetic research uses a wide range of molecular biological techniques to further understanding of epigenetic phenomena, including chromatin immunoprecipitation (together with its large-scale variants ChIP-on-chip and ChIP-Seq), fluorescent in situ hybridization, methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes, DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID) and bisulfite sequencing. Furthermore, the use of bioinformatics methods has a role in computational epigenetics.

Mechanisms

Epigenetic mechanisms are sensitive to environmental effects, and key participants in shaping an adult phenotype. Several types of epigenetic inheritance systems may play a role in what has become known as cell memory, note however that not all of these are universally accepted to be examples of epigenetics.

Covalent modifications

Covalent modifications of either DNA (e.g. cytosine methylation and hydroxymethylation) or of histone proteins (e.g. lysine acetylation, lysine and arginine methylation, serine and threonine phosphorylation, and lysine ubiquitination and sumoylation) play central roles in many types of epigenetic inheritance. Therefore, the word "epigenetics" is sometimes used as a synonym for these processes. However, this can be misleading. Chromatin remodeling is not always inherited, and not all epigenetic inheritance involves chromatin remodeling. In 2019, a further lysine modification appeared in the scientific literature linking epigenetics modification to cell metabolism, i.e. Lactylation.

Because the phenotype of a cell or individual is affected by which of its genes are transcribed, heritable transcription states can give rise to epigenetic effects. There are several layers of regulation of gene expression. One way that genes are regulated is through the remodeling of chromatin. Chromatin is the complex of DNA and the histone proteins with which it associates. If the way that DNA is wrapped around the histones changes, gene expression can change as well. Chromatin remodeling is accomplished through two main mechanisms:

- The first way is post translational modification of the amino acids that make up histone proteins. Histone proteins are made up of long chains of amino acids. If the amino acids that are in the chain are changed, the shape of the histone might be modified. DNA is not completely unwound during replication. It is possible, then, that the modified histones may be carried into each new copy of the DNA. Once there, these histones may act as templates, initiating the surrounding new histones to be shaped in the new manner. By altering the shape of the histones around them, these modified histones would ensure that a lineage-specific transcription program is maintained after cell division.

- The second way is the addition of methyl groups to the DNA, mostly at CpG sites, to convert cytosine to 5-methylcytosine. 5-Methylcytosine performs much like a regular cytosine, pairing with a guanine in double-stranded DNA. However when methylated cytosines are present in CpG sites in the promoter and enhancer regions of genes, the genes are often repressed. When methylated cytosines are present in CpG sites in the gene body (in the coding region excluding the transcription start site) expression of the gene is often enhanced. Transcription of a gene usually depends on a transcription factor binding to a (10 base or less) recognition sequence at the promoter region of that gene. About 22% of transcription factors are inhibited from binding when the recognition sequence has a methylated cytosine. In addition, presence of methylated cytosines at a promoter region can attract methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins. All MBDs interact with nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase complexes, which leads to gene silencing. In addition, another covalent modification involving methylated cytosine is its demethylation by TET enzymes. Hundreds of such demethylations occur, for instance, during learning and memory forming events in neurons.

Mechanisms of heritability of histone state are not well understood; however, much is known about the mechanism of heritability of DNA methylation state during cell division and differentiation. Heritability of methylation state depends on certain enzymes (such as DNMT1) that have a higher affinity for 5-methylcytosine than for cytosine. If this enzyme reaches a "hemimethylated" portion of DNA (where 5-methylcytosine is in only one of the two DNA strands) the enzyme will methylate the other half.

Although histone modifications occur throughout the entire sequence, the unstructured N-termini of histones (called histone tails) are particularly highly modified. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, ubiquitylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, ribosylation and citrullination. Acetylation is the most highly studied of these modifications. For example, acetylation of the K14 and K9 lysines of the tail of histone H3 by histone acetyltransferase enzymes (HATs) is generally related to transcriptional competence.

One mode of thinking is that this tendency of acetylation to be associated with "active" transcription is biophysical in nature. Because it normally has a positively charged nitrogen at its end, lysine can bind the negatively charged phosphates of the DNA backbone. The acetylation event converts the positively charged amine group on the side chain into a neutral amide linkage. This removes the positive charge, thus loosening the DNA from the histone. When this occurs, complexes like SWI/SNF and other transcriptional factors can bind to the DNA and allow transcription to occur. This is the "cis" model of the epigenetic function. In other words, changes to the histone tails have a direct effect on the DNA itself.

Another model of epigenetic function is the "trans" model. In this model, changes to the histone tails act indirectly on the DNA. For example, lysine acetylation may create a binding site for chromatin-modifying enzymes (or transcription machinery as well). This chromatin remodeler can then cause changes to the state of the chromatin. Indeed, a bromodomain – a protein domain that specifically binds acetyl-lysine – is found in many enzymes that help activate transcription, including the SWI/SNF complex. It may be that acetylation acts in this and the previous way to aid in transcriptional activation.

The idea that modifications act as docking modules for related factors is borne out by histone methylation as well. Methylation of lysine 9 of histone H3 has long been associated with constitutively transcriptionally silent chromatin (constitutive heterochromatin). It has been determined that a chromodomain (a domain that specifically binds methyl-lysine) in the transcriptionally repressive protein HP1 recruits HP1 to K9 methylated regions. One example that seems to refute this biophysical model for methylation is that tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is strongly associated with (and required for full) transcriptional activation. Tri-methylation, in this case, would introduce a fixed positive charge on the tail.

It has been shown that the histone lysine methyltransferase (KMT) is responsible for this methylation activity in the pattern of histones H3 & H4. This enzyme utilizes a catalytically active site called the SET domain (Suppressor of variegation, Enhancer of zeste, Trithorax). The SET domain is a 130-amino acid sequence involved in modulating gene activities. This domain has been demonstrated to bind to the histone tail and causes the methylation of the histone.

Differing histone modifications are likely to function in differing ways; acetylation at one position is likely to function differently from acetylation at another position. Also, multiple modifications may occur at the same time, and these modifications may work together to change the behavior of the nucleosome. The idea that multiple dynamic modifications regulate gene transcription in a systematic and reproducible way is called the histone code, although the idea that histone state can be read linearly as a digital information carrier has been largely debunked. One of the best-understood systems that orchestrate chromatin-based silencing is the SIR protein based silencing of the yeast hidden mating-type loci HML and HMR.

DNA methylation frequently occurs in repeated sequences, and helps to suppress the expression and mobility of 'transposable elements': Because 5-methylcytosine can be spontaneously deaminated (replacing nitrogen by oxygen) to thymidine, CpG sites are frequently mutated and become rare in the genome, except at CpG islands where they remain unmethylated. Epigenetic changes of this type thus have the potential to direct increased frequencies of permanent genetic mutation. DNA methylation patterns are known to be established and modified in response to environmental factors by a complex interplay of at least three independent DNA methyltransferases, DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, the loss of any of which is lethal in mice. DNMT1 is the most abundant methyltransferase in somatic cells, localizes to replication foci, has a 10–40-fold preference for hemimethylated DNA and interacts with the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA).

By preferentially modifying hemimethylated DNA, DNMT1 transfers patterns of methylation to a newly synthesized strand after DNA replication, and therefore is often referred to as the ‘maintenance' methyltransferase. DNMT1 is essential for proper embryonic development, imprinting and X-inactivation. To emphasize the difference of this molecular mechanism of inheritance from the canonical Watson-Crick base-pairing mechanism of transmission of genetic information, the term 'Epigenetic templating' was introduced. Furthermore, in addition to the maintenance and transmission of methylated DNA states, the same principle could work in the maintenance and transmission of histone modifications and even cytoplasmic (structural) heritable states.

Histones H3 and H4 can also be manipulated through demethylation using histone lysine demethylase (KDM). This recently identified enzyme has a catalytically active site called the Jumonji domain (JmjC). The demethylation occurs when JmjC utilizes multiple cofactors to hydroxylate the methyl group, thereby removing it. JmjC is capable of demethylating mono-, di-, and tri-methylated substrates.

Chromosomal regions can adopt stable and heritable alternative states resulting in bistable gene expression without changes to the DNA sequence. Epigenetic control is often associated with alternative covalent modifications of histones. The stability and heritability of states of larger chromosomal regions are suggested to involve positive feedback where modified nucleosomes recruit enzymes that similarly modify nearby nucleosomes. A simplified stochastic model for this type of epigenetics is found here.

It has been suggested that chromatin-based transcriptional regulation could be mediated by the effect of small RNAs. Small interfering RNAs can modulate transcriptional gene expression via epigenetic modulation of targeted promoters.

RNA transcripts

Sometimes a gene, after being turned on, transcribes a product that (directly or indirectly) maintains the activity of that gene. For example, Hnf4 and MyoD enhance the transcription of many liver-specific and muscle-specific genes, respectively, including their own, through the transcription factor activity of the proteins they encode. RNA signalling includes differential recruitment of a hierarchy of generic chromatin modifying complexes and DNA methyltransferases to specific loci by RNAs during differentiation and development. Other epigenetic changes are mediated by the production of different splice forms of RNA, or by formation of double-stranded RNA (RNAi). Descendants of the cell in which the gene was turned on will inherit this activity, even if the original stimulus for gene-activation is no longer present. These genes are often turned on or off by signal transduction, although in some systems where syncytia or gap junctions are important, RNA may spread directly to other cells or nuclei by diffusion. A large amount of RNA and protein is contributed to the zygote by the mother during oogenesis or via nurse cells, resulting in maternal effect phenotypes. A smaller quantity of sperm RNA is transmitted from the father, but there is recent evidence that this epigenetic information can lead to visible changes in several generations of offspring.

MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are members of non-coding RNAs that range in size from 17 to 25 nucleotides. miRNAs regulate a large variety of biological functions in plants and animals. So far, in 2013, about 2000 miRNAs have been discovered in humans and these can be found online in a miRNA database. Each miRNA expressed in a cell may target about 100 to 200 messenger RNAs(mRNAs) that it downregulates. Most of the downregulation of mRNAs occurs by causing the decay of the targeted mRNA, while some downregulation occurs at the level of translation into protein.

It appears that about 60% of human protein coding genes are regulated by miRNAs. Many miRNAs are epigenetically regulated. About 50% of miRNA genes are associated with CpG islands, that may be repressed by epigenetic methylation. Transcription from methylated CpG islands is strongly and heritably repressed. Other miRNAs are epigenetically regulated by either histone modifications or by combined DNA methylation and histone modification.

mRNA

In 2011, it was demonstrated that the methylation of mRNA plays a critical role in human energy homeostasis. The obesity-associated FTO gene is shown to be able to demethylate N6-methyladenosine in RNA.

sRNAs

sRNAs are small (50–250 nucleotides), highly structured, non-coding RNA fragments found in bacteria. They control gene expression including virulence genes in pathogens and are viewed as new targets in the fight against drug-resistant bacteria. They play an important role in many biological processes, binding to mRNA and protein targets in prokaryotes. Their phylogenetic analyses, for example through sRNA–mRNA target interactions or protein binding properties, are used to build comprehensive databases. sRNA-gene maps based on their targets in microbial genomes are also constructed.

Prions

Prions are infectious forms of proteins. In general, proteins fold into discrete units that perform distinct cellular functions, but some proteins are also capable of forming an infectious conformational state known as a prion. Although often viewed in the context of infectious disease, prions are more loosely defined by their ability to catalytically convert other native state versions of the same protein to an infectious conformational state. It is in this latter sense that they can be viewed as epigenetic agents capable of inducing a phenotypic change without a modification of the genome.

Fungal prions are considered by some to be epigenetic because the infectious phenotype caused by the prion can be inherited without modification of the genome. PSI+ and URE3, discovered in yeast in 1965 and 1971, are the two best studied of this type of prion. Prions can have a phenotypic effect through the sequestration of protein in aggregates, thereby reducing that protein's activity. In PSI+ cells, the loss of the Sup35 protein (which is involved in termination of translation) causes ribosomes to have a higher rate of read-through of stop codons, an effect that results in suppression of nonsense mutations in other genes. The ability of Sup35 to form prions may be a conserved trait. It could confer an adaptive advantage by giving cells the ability to switch into a PSI+ state and express dormant genetic features normally terminated by stop codon mutations.

Prion-based epigenetics has also been observed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Structural inheritance

In ciliates such as Tetrahymena and Paramecium, genetically identical cells show heritable differences in the patterns of ciliary rows on their cell surface. Experimentally altered patterns can be transmitted to daughter cells. It seems existing structures act as templates for new structures. The mechanisms of such inheritance are unclear, but reasons exist to assume that multicellular organisms also use existing cell structures to assemble new ones.

Nucleosome positioning

Eukaryotic genomes have numerous nucleosomes. Nucleosome position is not random, and determine the accessibility of DNA to regulatory proteins. Promoters active in different tissues have been shown to have different nucleosome positioning features. This determines differences in gene expression and cell differentiation. It has been shown that at least some nucleosomes are retained in sperm cells (where most but not all histones are replaced by protamines). Thus nucleosome positioning is to some degree inheritable. Recent studies have uncovered connections between nucleosome positioning and other epigenetic factors, such as DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation.

Histone variants

Different histone variants are incorporated into specific regions of the genome non-randomly. Their differential biochemical characteristics can affect genome functions via their roles in gene regulation, and maintenance of chromosome structures.

Genomic architecture

The three-dimensional configuration of the genome (the 3D genome) is complex, dynamic and crucial for regulating genomic function and nuclear processes such as DNA replication, transcription and DNA-damage repair.

Functions and consequences

Development

Developmental epigenetics can be divided into predetermined and probabilistic epigenesis. Predetermined epigenesis is a unidirectional movement from structural development in DNA to the functional maturation of the protein. "Predetermined" here means that development is scripted and predictable. Probabilistic epigenesis on the other hand is a bidirectional structure-function development with experiences and external molding development.

Somatic epigenetic inheritance, particularly through DNA and histone covalent modifications and nucleosome repositioning, is very important in the development of multicellular eukaryotic organisms. The genome sequence is static (with some notable exceptions), but cells differentiate into many different types, which perform different functions, and respond differently to the environment and intercellular signaling. Thus, as individuals develop, morphogens activate or silence genes in an epigenetically heritable fashion, giving cells a memory. In mammals, most cells terminally differentiate, with only stem cells retaining the ability to differentiate into several cell types ("totipotency" and "multipotency"). In mammals, some stem cells continue producing newly differentiated cells throughout life, such as in neurogenesis, but mammals are not able to respond to loss of some tissues, for example, the inability to regenerate limbs, which some other animals are capable of. Epigenetic modifications regulate the transition from neural stem cells to glial progenitor cells (for example, differentiation into oligodendrocytes is regulated by the deacetylation and methylation of histones. Unlike animals, plant cells do not terminally differentiate, remaining totipotent with the ability to give rise to a new individual plant. While plants do utilize many of the same epigenetic mechanisms as animals, such as chromatin remodeling, it has been hypothesized that some kinds of plant cells do not use or require "cellular memories", resetting their gene expression patterns using positional information from the environment and surrounding cells to determine their fate.

Epigenetic changes can occur in response to environmental exposure – for example, maternal dietary supplementation with genistein (250 mg/kg) have epigenetic changes affecting expression of the agouti gene, which affects their fur color, weight, and propensity to develop cancer. Ongoing research is focused on exploring the impact of other known teratogens, such as diabetic embryopathy, on methylation signatures.

Controversial results from one study suggested that traumatic experiences might produce an epigenetic signal that is capable of being passed to future generations. Mice were trained, using foot shocks, to fear a cherry blossom odor. The investigators reported that the mouse offspring had an increased aversion to this specific odor. They suggested epigenetic changes that increase gene expression, rather than in DNA itself, in a gene, M71, that governs the functioning of an odor receptor in the nose that responds specifically to this cherry blossom smell. There were physical changes that correlated with olfactory (smell) function in the brains of the trained mice and their descendants. Several criticisms were reported, including the study's low statistical power as evidence of some irregularity such as bias in reporting results. Due to limits of sample size, there is a probability that an effect will not be demonstrated to within statistical significance even if it exists. The criticism suggested that the probability that all the experiments reported would show positive results if an identical protocol was followed, assuming the claimed effects exist, is merely 0.4%. The authors also did not indicate which mice were siblings, and treated all of the mice as statistically independent. The original researchers pointed out negative results in the paper's appendix that the criticism omitted in its calculations, and undertook to track which mice were siblings in the future.

Transgenerational

Epigenetic mechanisms were a necessary part of the evolutionary origin of cell differentiation. Although epigenetics in multicellular organisms is generally thought to be a mechanism involved in differentiation, with epigenetic patterns "reset" when organisms reproduce, there have been some observations of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (e.g., the phenomenon of paramutation observed in maize). Although most of these multigenerational epigenetic traits are gradually lost over several generations, the possibility remains that multigenerational epigenetics could be another aspect to evolution and adaptation. As mentioned above, some define epigenetics as heritable.

A sequestered germ line or Weismann barrier is specific to animals, and epigenetic inheritance is more common in plants and microbes. Eva Jablonka, Marion J. Lamb and Étienne Danchin have argued that these effects may require enhancements to the standard conceptual framework of the modern synthesis and have called for an extended evolutionary synthesis. Other evolutionary biologists, such as John Maynard Smith, have incorporated epigenetic inheritance into population-genetics models or are openly skeptical of the extended evolutionary synthesis (Michael Lynch). Thomas Dickins and Qazi Rahman state that epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification are genetically inherited under the control of natural selection and therefore fit under the earlier "modern synthesis".

Two important ways in which epigenetic inheritance can differ from traditional genetic inheritance, with important consequences for evolution, are:

- rates of epimutation can be much faster than rates of mutation

- the epimutations are more easily reversible

In plants, heritable DNA methylation mutations are 100,000 times more likely to occur compared to DNA mutations. An epigenetically inherited element such as the PSI+ system can act as a "stop-gap", good enough for short-term adaptation that allows the lineage to survive for long enough for mutation and/or recombination to genetically assimilate the adaptive phenotypic change. The existence of this possibility increases the evolvability of a species.

More than 100 cases of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance phenomena have been reported in a wide range of organisms, including prokaryotes, plants, and animals. For instance, mourning-cloak butterflies will change color through hormone changes in response to experimentation of varying temperatures.

The filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa is a prominent model system for understanding the control and function of cytosine methylation. In this organism, DNA methylation is associated with relics of a genome-defense system called RIP (repeat-induced point mutation) and silences gene expression by inhibiting transcription elongation.

The yeast prion PSI is generated by a conformational change of a translation termination factor, which is then inherited by daughter cells. This can provide a survival advantage under adverse conditions, examplifying epigenetic regulation which enables unicellular organisms to respond rapidly to environmental stress. Prions can be viewed as epigenetic agents capable of inducing a phenotypic change without modification of the genome.

Direct detection of epigenetic marks in microorganisms is possible with single molecule real time sequencing, in which polymerase sensitivity allows for measuring methylation and other modifications as a DNA molecule is being sequenced. Several projects have demonstrated the ability to collect genome-wide epigenetic data in bacteria.

Epigenetics in bacteria

While epigenetics is of fundamental importance in eukaryotes, especially metazoans, it plays a different role in bacteria. Most importantly, eukaryotes use epigenetic mechanisms primarily to regulate gene expression which bacteria rarely do. However, bacteria make widespread use of postreplicative DNA methylation for the epigenetic control of DNA-protein interactions. Bacteria also use DNA adenine methylation (rather than DNA cytosine methylation) as an epigenetic signal. DNA adenine methylation is important in bacteria virulence in organisms such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Vibrio, Yersinia, Haemophilus, and Brucella. In Alphaproteobacteria, methylation of adenine regulates the cell cycle and couples gene transcription to DNA replication. In Gammaproteobacteria, adenine methylation provides signals for DNA replication, chromosome segregation, mismatch repair, packaging of bacteriophage, transposase activity and regulation of gene expression. There exists a genetic switch controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) that allows the bacterium to randomly change its characteristics into six alternative states that could pave the way to improved vaccines. Each form is randomly generated by a phase variable methylation system. The ability of the pneumococcus to cause deadly infections is different in each of these six states. Similar systems exist in other bacterial genera. In Firmicutes such as Clostridioides difficile, adenine methylation regulates sporulation, biofilm formation and host-adaptation.

Medicine

Epigenetics has many and varied potential medical applications. In 2008, the National Institutes of Health announced that $190 million had been earmarked for epigenetics research over the next five years. In announcing the funding, government officials noted that epigenetics has the potential to explain mechanisms of aging, human development, and the origins of cancer, heart disease, mental illness, as well as several other conditions. Some investigators, like Randy Jirtle, Ph.D., of Duke University Medical Center, think epigenetics may ultimately turn out to have a greater role in disease than genetics.

Twins

Direct comparisons of identical twins constitute an optimal model for interrogating environmental epigenetics. In the case of humans with different environmental exposures, monozygotic (identical) twins were epigenetically indistinguishable during their early years, while older twins had remarkable differences in the overall content and genomic distribution of 5-methylcytosine DNA and histone acetylation. The twin pairs who had spent less of their lifetime together and/or had greater differences in their medical histories were those who showed the largest differences in their levels of 5-methylcytosine DNA and acetylation of histones H3 and H4.

Dizygotic (fraternal) and monozygotic (identical) twins show evidence of epigenetic influence in humans. DNA sequence differences that would be abundant in a singleton-based study do not interfere with the analysis. Environmental differences can produce long-term epigenetic effects, and different developmental monozygotic twin subtypes may be different with respect to their susceptibility to be discordant from an epigenetic point of view.

A high-throughput study, which denotes technology that looks at extensive genetic markers, focused on epigenetic differences between monozygotic twins to compare global and locus-specific changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications in a sample of 40 monozygotic twin pairs. In this case, only healthy twin pairs were studied, but a wide range of ages was represented, between 3 and 74 years. One of the major conclusions from this study was that there is an age-dependent accumulation of epigenetic differences between the two siblings of twin pairs. This accumulation suggests the existence of epigenetic "drift". Epigenetic drift is the term given to epigenetic modifications as they occur as a direct function with age. While age is a known risk factor for many diseases, age-related methylation has been found to occur differentially at specific sites along the genome. Over time, this can result in measurable differences between biological and chronological age. Epigenetic changes have been found to be reflective of lifestyle and may act as functional biomarkers of disease before clinical threshold is reached.

A more recent study, where 114 monozygotic twins and 80 dizygotic twins were analyzed for the DNA methylation status of around 6000 unique genomic regions, concluded that epigenetic similarity at the time of blastocyst splitting may also contribute to phenotypic similarities in monozygotic co-twins. This supports the notion that microenvironment at early stages of embryonic development can be quite important for the establishment of epigenetic marks. Congenital genetic disease is well understood and it is clear that epigenetics can play a role, for example, in the case of Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome. These are normal genetic diseases caused by gene deletions or inactivation of the genes but are unusually common because individuals are essentially hemizygous because of genomic imprinting, and therefore a single gene knock out is sufficient to cause the disease, where most cases would require both copies to be knocked out.

Genomic imprinting

Some human disorders are associated with genomic imprinting, a phenomenon in mammals where the father and mother contribute different epigenetic patterns for specific genomic loci in their germ cells. The best-known case of imprinting in human disorders is that of Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome – both can be produced by the same genetic mutation, chromosome 15q partial deletion, and the particular syndrome that will develop depends on whether the mutation is inherited from the child's mother or from their father. This is due to the presence of genomic imprinting in the region. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is also associated with genomic imprinting, often caused by abnormalities in maternal genomic imprinting of a region on chromosome 11.

Methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) is a transcriptional regulator that must be phosphorylated before releasing from the BDNF promoter, allowing transcription. Rett syndrome is underlain by mutations in the MeCP2 gene despite no large-scale changes in expression of MeCP2 being found in microarray analyses. BDNF is downregulated in the MECP2 mutant resulting in Rett syndrome, as well as the increase of early neural senescence and accumulation of damaged DNA.

In the Överkalix study, paternal (but not maternal) grandsons of Swedish men who were exposed during preadolescence to famine in the 19th century were less likely to die of cardiovascular disease. If food was plentiful, then diabetes mortality in the grandchildren increased, suggesting that this was a transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. The opposite effect was observed for females – the paternal (but not maternal) granddaughters of women who experienced famine while in the womb (and therefore while their eggs were being formed) lived shorter lives on average.

Cancer

A variety of epigenetic mechanisms can be perturbed in different types of cancer. Epigenetic alterations of DNA repair genes or cell cycle control genes are very frequent in sporadic (non-germ line) cancers, being significantly more common than germ line (familial) mutations in these sporadic cancers. Epigenetic alterations are important in cellular transformation to cancer, and their manipulation holds great promise for cancer prevention, detection, and therapy. Several medications which have epigenetic impact are used in several of these diseases. These aspects of epigenetics are addressed in cancer epigenetics.

Diabetic wound healing

Epigenetic modifications have given insight into the understanding of the pathophysiology of different disease conditions. Though, they are strongly associated with cancer, their role in other pathological conditions are of equal importance. It appears that the hyperglycaemic environment could imprint such changes at the genomic level, that macrophages are primed towards a pro-inflammatory state and could fail to exhibit any phenotypic alteration towards the pro-healing type. This phenomenon of altered Macrophage Polarization is mostly associated with all the diabetic complications in a clinical set-up. As of 2018, several reports reveal the relevance of different epigenetic modifications with respect to diabetic complications. Sooner or later, with the advancements in biomedical tools, the detection of such biomarkers as prognostic and diagnostic tools in patients could possibly emerge out as alternative approaches. It is noteworthy to mention here that the use of epigenetic modifications as therapeutic targets warrant extensive preclinical as well as clinical evaluation prior to use.

Examples of drugs altering gene expression from epigenetic events

The use of beta-lactam antibiotics can alter glutamate receptor activity and the action of cyclosporine on multiple transcription factors. Additionally, lithium can impact autophagy of aberrant proteins, and opioid drugs via chronic use can increase the expression of genes associated with addictive phenotypes.

Psychology and psychiatry

Early life stress

In a groundbreaking 2003 report, Caspi and colleagues demonstrated that in a robust cohort of over one-thousand subjects assessed multiple times from preschool to adulthood, subjects who carried one or two copies of the short allele of the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism exhibited higher rates of adult depression and suicidality when exposed to childhood maltreatment when compared to long allele homozygotes with equal ELS exposure.

Parental nutrition, in utero exposure to stress or endocrine disrupting chemicals, male-induced maternal effects such as the attraction of differential mate quality, and maternal as well as paternal age, and offspring gender could all possibly influence whether a germline epimutation is ultimately expressed in offspring and the degree to which intergenerational inheritance remains stable throughout posterity. However, whether and to what extent epigenetic effects can be transmitted across generations remains unclear, particularly in humans.

Addiction

Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system which arises through transcriptional and neuroepigenetic mechanisms and occurs over time from chronically high levels of exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., morphine, cocaine, sexual intercourse, gambling, etc.). Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of addictive phenotypes has been noted to occur in preclinical studies. However, robust evidence in support of the persistence of epigenetic effects across multiple generations has yet to be established in humans; for example, an epigenetic effect of prenatal exposure to smoking that is observed in great-grandchildren who had not been exposed.

In the meantime, however, evidence has been accumulating that the use of Cannabis by mothers during - and also by both parents before - pregnancy leads to epigenetic alterations in neonates that are known to be associated with an increased risk to develop psychiatric disorders later during their lives, such as autism, ADHD, schizophrenia, addictive behavior, and others.

Depression

Epigenetic inheritance of depression-related phenotypes has also been reported in a preclinical study. Inheritance of paternal stress-induced traits across generations involved small non-coding RNA signals transmitted via the paternal germline.

Research

The two forms of heritable information, namely genetic and epigenetic, are collectively denoted as dual inheritance. Members of the APOBEC/AID family of cytosine deaminases may concurrently influence genetic and epigenetic inheritance using similar molecular mechanisms, and may be a point of crosstalk between these conceptually compartmentalized processes.

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics induce epigenetic changes in mammalian cells through iron chelation. This leads to epigenetic effects through inhibition of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that require iron as a co-factor.

Various pharmacological agents are applied for the production of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or maintain the embryonic stem cell (ESC) phenotypic via epigenetic approach. Adult stem cells like bone marrow stem cells have also shown a potential to differentiate into cardiac competent cells when treated with G9a histone methyltransferase inhibitor BIX01294.

Pseudoscience

As epigenetics is in the early stages of development as a science and is surrounded by sensationalism in the public media, David Gorski and geneticist Adam Rutherford have advised caution against the proliferation of false and pseudoscientific conclusions by new age authors making unfounded suggestions that a person's genes and health can be manipulated by mind control. Misuse of the scientific term by quack authors has produced misinformation among the general public.