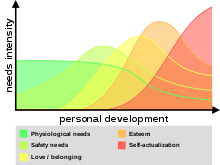

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is an idea in psychology proposed by American Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper "A Theory of Human Motivation" in the journal Psychological Review. Maslow subsequently extended the idea to include his observations of humans' innate curiosity. His theories parallel many other theories of human developmental psychology, some of which focus on describing the stages of growth in humans. He then created a classification system which reflected the universal needs of society as its base and then proceeding to more acquired emotions. His theories, including the hierarchy, may have been influenced by teachings and philosophy of the Blackfeet tribe, where he spent several weeks prior to writing his influential paper. The hierarchy of needs is split between deficiency needs and growth needs. The theory is usually shown as a triangle in illustrations.

The hierarchy of needs is a psychological idea but also a "... valuable assessment tool ... ". This tool is utilized in many fields that involve working and taking care of people such as but not limited to: health care workers, educators, social workers, life skill coaches, and many more. Maslow's hierarchy pyramid is frequently used because it visualizes the needs that one must have met in order to reach self-actualization. This concept was created as Maslow "studied and observed monkeys ... noticing their unusual pattern of behavior that addressed priorities based on individual needs". The two key elements involved within this theory is the individual and the priority, which connects them to intrinsic behavioral motivation.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is used to study how humans intrinsically partake in behavioral motivation. Maslow used the terms "physiological", "safety", "belonging and love", "social needs" or "esteem", and "self-actualization" to describe the pattern through which human motivations generally move. This means that in order for motivation to arise at the next stage, each stage must be satisfied within the individual themselves. Additionally, this hierarchy is a main base in knowing how effort and motivation are correlated when discussing human behavior. Each of these individual levels contains a certain amount of internal sensation that must be met in order for an individual to complete their hierarchy. The goal in Maslow's hierarchy is to attain the fifth level or stage: self-actualization.

Maslow's idea was fully expressed in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality. The hierarchy remains a very popular framework in sociology research, including management training and higher psychology instruction. Maslow's classification hierarchy has been revised over time. The original hierarchy states that a lower level must be completely satisfied and fulfilled before moving onto a higher pursuit. However, today scholars prefer to think of these levels as continuously overlapping each other. This means that the lower levels may take precedence back over the other levels at any point in time.[4]

Stages

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often portrayed in the shape of a pyramid, with the largest, most fundamental needs at the bottom, and the need for self-actualization and transcendence at the top. In other words, the idea is that individuals' most basic needs must be met before they become motivated to achieve higher-level needs. However, it has been pointed out that, although the ideas behind the hierarchy are Maslow's, the pyramid itself does not exist anywhere in Maslow's original work.

The most fundamental four layers of the pyramid contain what Maslow called "deficiency needs" or "d-needs": esteem, friendship and love, security, and physical needs. If these "deficiency needs" are not met – except for the most fundamental (physiological) need – there may not be a physical indication, but the individual will feel anxious and tense. Deprivation is what causes deficiency, so when one has needs are unmet, this motivates them to fulfill what they are being denied. Maslow's idea suggests that the most basic level of needs must be met before the individual will strongly desire (or focus motivation upon) the secondary or higher-level needs. Maslow also coined the term "metamotivation" to describe the motivation of people who go beyond the scope of the basic needs and strive for constant betterment.

The human brain is a complex system and has parallel processes running at the same time, thus many different motivations from various levels of Maslow's hierarchy can occur at the same time. Maslow spoke clearly about these levels and their satisfaction in terms such as "relative", "general", and "primarily". Instead of stating that the individual focuses on a certain need at any given time, Maslow stated that a certain need "dominates" the human organism.[8] Thus Maslow acknowledged the likelihood that the different levels of motivation could occur at any time in the human mind, but he focused on identifying the basic types of motivation and the order in which they would tend to be met.

Physiological needs

Physiological needs are the base of the hierarchy. These needs are the biological component for human survival. According to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, physiological needs are factored in internal motivation. According to Maslow's theory, humans are compelled to satisfy physiological needs first in order to pursue higher levels of intrinsic satisfaction. In order to advance higher-level needs in Maslow's hierarchy, physiological needs must be met first. This means that if a person is struggling to meet their physiological needs, they are unwilling to seek safety, belonging, esteem, and self-actualization on their own.

Physiological needs include:

These physiological needs must be met in order for the human body to remain in homeostasis. Without air, there is not much that the human body can do without this physiological element, which is why these needs are critical in order to "... meet the very basic essentials of life ..." This allows for cravings such as hunger and thirst to be satisfied and not disrupt regulation of the body.

Safety needs

Once a person's physiological needs are satisfied, their safety needs take precedence and dominate behavior. In the absence of physical safety – due to war, natural disaster, family violence, childhood abuse, etc. and/or in the absence of economic safety – (due to an economic crisis and lack of work opportunities) these safety needs manifest themselves in ways such as a preference for job security, grievance procedures for protecting the individual from unilateral authority, savings accounts, insurance policies, disability accommodations, etc. This level is more likely to predominate in children as they generally have a greater need to feel safe - especially children that have disabilities. Adults are also impacted by this, typically in economic matters, "... adults are not immune to the need of safety". It includes shelter, job security, health, and safe environments. If a person does not feel safe in an environment, they will seek safety before attempting to meet any higher level of survival. This is why the "... goal of consistently meeting the need for safety is to have stability in one's life", stability brings back the concept of homeostasis for humans which our bodies need.

Safety needs include:

Love and social belonging needs

After physiological and safety needs are fulfilled, the third level of human needs is interpersonal and involves feelings of belongingness. According to Maslow, humans possess an effective need for a sense of belonging and acceptance among social groups, regardless of whether these groups are large or small; being a part of a group is crucial, regardless if it is work, sports, friends or family. The sense of belongingness is "being comfortable with and connection to others that results from receiving acceptance, respect, and love". For example, some large social groups may include clubs, co-workers, religious groups, professional organizations, sports teams, gangs, and online communities. Some examples of small social connections include family members, intimate partners, mentors, colleagues, and confidants. Humans need to love and be loved – both sexually and non-sexually – by others. Many people become susceptible to loneliness, social anxiety, and clinical depression in the absence of this love or belonging element. This need is especially strong in childhood and it can override the need for safety as witnessed in children who cling to abusive parents. Deficiencies due to hospitalism, neglect, shunning, ostracism, etc. can adversely affect the individual's ability to form and maintain emotionally significant relationships in general. Mental health can be a huge factor when it comes to an individual's needs and development. When an individual's needs are not met, it can cause depression during adolescence. When an individual grows up in a higher-income family, it is much more likely that they will have a lower rate of depression. This is because all of their basic needs are met. Studies have shown that when a family goes through financial stress for a prolonged amount of time, depression rates are higher, not only because their basic needs are not being met, but because this stress puts a strain on the parent-child relationship. The parent(s) is stressed about providing for their children, and they are also likely to spend less time at home because they are working more to make more money and provide for their family.

Social belonging needs include:

- Family

- Friendship

- Intimacy

- Trust

- Acceptance

- Receiving and giving love and affection

This need for belonging may overcome the physiological and security needs, depending on the strength of the peer pressure. In contrast, for some individuals, the need for self-esteem is more important than the need for belonging; and for others, the need for creative fulfillment may supersede even the most basic needs.

Esteem needs

Esteem is the respect and admiration of a person, but also "... self-respect and respect from others". Most people have a need for a stable esteem, meaning which is soundly based on real capacity or achievement. Maslow noted two versions of esteem needs. The "lower" version of esteem is the need for respect from others, and may include a need for status, recognition, fame, prestige, and attention. The "higher" version of esteem is the need for self-respect, and can include a need for strength, competence, mastery, self-confidence, independence, and freedom. This "higher" version takes guidelines, the "hierarchies are interrelated rather than sharply separated". This means that esteem and the subsequent levels are not strictly separated; instead, the levels are closely related.

Esteem comes from day to day experiences, that provide a learning opportunity which allows us to discover ourselves. This is incredibly important within children, which is why giving them "... the opportunity to discover they are competent and capable learners". In order to boost this adults must provide opportunities for children to have successful and positive experiences to give children a greater "... sense of self". Adults, especially parents and educators must create and ensure an environment for children that is supportive and provides them with opportunities that "helps children see themselves as respectable, capable individuals" . It can also be found that "Maslow indicated that the need for respect or reputation is most important for children ... and precedes real self-esteem or dignity", which reflects the two aspects of esteem: for oneself and for others.

Extended Hierarchy of Needs

Cognitive needs

After esteem needs, cognitive needs come next in the hierarchy of needs. People have cognitive needs such as creativity, foresight, curiosity, and meaning. Individuals who enjoy activities that require deliberation and brainstorming have a greater need for cognition. Individuals who are unmotivated to participate in the activity, on the other hand, have a low demand for cognitive abilities. It has been said that Maslow's hierarchy of needs can be extended after esteem needs into two more categories: cognitive needs and aesthetic needs. Cognitive needs crave meaning, in this category mentally for information, comprehension and curiosity - this creates a will to learn and attain knowledge. In an educational viewpoint, Maslow wanting humans to have intrinsic motivation to become educated people.

Aesthetic needs

After reaching ones cognitive needs it would progress to aesthetic needs, to beautify ones life. This would consist of having the ability to appreciate the beauty within the world around ones self, on a day to day basis. According to Maslow's theories, in order to progress toward Self-Actualization, humans require beautiful imagery or novel and aesthetically pleasing experiences. Humans must immerse themselves in nature's splendor while paying close attention to and observing their surroundings in order to extract the world's beauty. This higher level need to connect with nature results in an endearing sense of intimacy with nature and all that is endearing. After reaching ones cognitive needs it would progress to aesthetic needs, to beautify oneself. This would consist of improving ones physical appearance to ensure its beauty to balance the rest of the body.

Self-actualization

"What a man can be, he must be." This quotation forms the basis of the perceived need for self-actualization. This level of need refers to the realization of one's full potential. Maslow describes this as the desire to accomplish everything that one can, to become the most that one can be. People may have a strong, particular desire to become an ideal parent, succeed athletically, or create paintings, pictures, or inventions. To understand this level of need, a person must not only succeed in the previous needs but master them. Self-actualization can be described as a value-based system when discussing its role in motivation. Self-actualization is understood as the goal or explicit motive, and the previous stages in Maslow's hierarchy fall in line to become the step-by-step process by which self-actualization is achievable; an explicit motive is the objective of a reward-based system that is used to intrinsically drive completion of certain values or goals. Individuals who are motivated to pursue this goal seek and understand how their needs, relationships, and sense of self are expressed through their behavior. Self-actualization needs include:

- Partner acquisition

- Parenting

- Utilizing and developing talents and abilities

- Pursuing goals

Transcendence needs

Maslow later subdivided the triangle's top to include self-transcendence, also known as spiritual needs. Spiritual needs differ from other types of needs in that they can be met on multiple levels. When this need is met, it produces feelings of integrity and raises things to a higher plane of existence. In his later years, Maslow explored a further dimension of motivation, while criticizing his original vision of self-actualization. By these later ideas, one finds the fullest realization in giving oneself to something beyond oneself—for example, in altruism or spirituality. He equated this with the desire to reach the infinite. "Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos".

Criticism

Although recent research appears to validate the existence of universal human needs, the hierarchy proposed by Maslow is called into question. Even so, Maslow's hierarchy of needs has widespread influence outside academia. As Uriel Abulof argues, "The continued resonance of Maslow's theory in popular imagination, however unscientific it may seem, is possibly the single most telling evidence of its significance: it explains human nature as something that most humans immediately recognize in themselves and others." Still, academically, Maslow's idea is heavily contested.

Methodology

Maslow studied what he called the master race of people such as Albert Einstein, Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frederick Douglass rather than mentally ill or neurotic people, writing that "the study of crippled, stunted, immature, and unhealthy specimens can yield only a cripple psychology and a cripple philosophy." Maslow studied the healthiest 1% of the college student population.

Ranking

Global ranking

In their extensive review of research based on Maslow's hierarchy, Wahba and Bridwell found little evidence for the ranking of needs that Maslow described or for the existence of a definite hierarchy at all.

The order in which the hierarchy is arranged has been criticized as being ethnocentric by Geert Hofstede. In turn, Hofstede's work has been criticized by others. Maslow's hierarchy of needs fails to illustrate and expand upon the difference between the social and intellectual needs of those raised in individualistic societies and those raised in collectivist societies. The needs and drives of those in individualistic societies tend to be more self-centered than those in collectivist societies, focusing on improvement of the self, with self-actualization being the apex of self-improvement. In collectivist societies, the needs of acceptance and community will outweigh the needs for freedom and individuality.

Ranking of sex

The position and value of sex on the pyramid has also been a source of criticism regarding Maslow's hierarchy. Maslow's hierarchy places sex in the needs category (above) along with food and breathing; it lists sex solely from an individualistic perspective. For example, sex is placed with other physiological needs which must be satisfied before a person considers "higher" levels of motivation. Some critics feel this placement of sex neglects the emotional, familial, and evolutionary implications of sex within the community, although others point out that this is true of all of the basic needs. In addition and in stark contrast to the other listed needs, it is clear that sex is not a universal need. This is evident in children, and even adults can choose to go their entire life without it yet still can obtain higher needs. The same cannot be said for the other listed needs.

Changes to the hierarchy by circumstance

The higher-order (self-esteem and self-actualization) and lower-order (physiological, safety, and love) needs classification of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is not universal and may vary across cultures due to individual differences and availability of resources in the region or geopolitical entity/country.

In one study, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of a thirteen-item scale showed there were two particularly important levels of needs in the US during the peacetime of 1993 to 1994: survival (physiological and safety) and psychological (love, self-esteem, and self-actualization). In 1991, a retrospective peacetime measure was established and collected during the Persian Gulf War and US citizens were asked to recall the importance of needs from the previous year. Once again, only two levels of needs were identified; therefore, people have the ability and competence to recall and estimate the importance of needs. For citizens in the Middle East (Egypt and Saudi Arabia), three levels of needs regarding importance and satisfaction surfaced during the 1990 retrospective peacetime. These three levels were completely different from those of the US citizens.

Changes regarding the importance and satisfaction of needs from the retrospective peacetime to the wartime due to stress varied significantly across cultures (the US vs. the Middle East). For the US citizens, there was only one level of needs since all needs were considered equally important. With regards to satisfaction of needs during the war, in the US there were three levels: physiological needs, safety needs, and psychological needs (social, self-esteem, and self-actualization). During the war, the satisfaction of physiological needs and safety needs were separated into two independent needs while during peacetime, they were combined as one. For the people of the Middle East, the satisfaction of needs changed from three levels to two during wartime.

A 1981 study looked at how Maslow's hierarchy might vary across age groups. A survey asked participants of varying ages to rate a set number of statements from most important to least important. The researchers found that children had higher physical need scores than the other groups, the love need emerged from childhood to young adulthood, the esteem need was highest among the adolescent group, young adults had the highest self-actualization level, and old age had the highest level of security, it was needed across all levels comparably. The authors argued that this suggested Maslow's hierarchy may be limited as a theory for developmental sequence since the sequence of the love need and the self-esteem need should be reversed according to age.

Definition of terms

Human or non-human needs

Abulof argues that while Maslow stresses that "motivation theory must be anthropocentric rather than animalcentric," he posits a largely animalistic hierarchy, crowned with a human edge: "Man's higher nature rests upon man's lower nature, needing it as a foundation and collapsing without this foundation… Our godlike qualities rest upon and need our animal qualities." Abulof notes that "all animals seek survival and safety, and many animals, especially mammals, also invest efforts to belong and gain esteem... The first four of Maslow's classical five rungs feature nothing exceptionally human." Even when it comes to "self-actualization", Abulof argues, it is unclear how distinctively human is the actualizing "self". After all, the latter, according to Maslow, constitutes "an inner, more biological, more instinctoid core of human nature," thus "the search for one's own intrinsic, authentic values" checks the human freedom of choice: "A musician must make music," so freedom is limited to merely the choice of instrument.