The practice of vegetarianism is strongly linked with a number of religious traditions worldwide. These include religions that originated in India, such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. With close to 85% of India's billion-plus population practicing these religions, India remains the country with the highest number of vegetarians in the world.

In Jainism, vegetarianism is mandatory for everyone; in Hinduism, Mahayana Buddhism and certain Dharmic religion such as Sikhism, it is promoted by scriptures and religious authorities but not mandatory. In the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), the Bahá'í Faith, vegetarianism is less commonly viewed as a religious obligation, although in all these faiths there are groups actively promoting vegetarianism on religious grounds, and many other faiths hold vegetarian and vegan idea among their tenets.

Religions originating in the Indian subcontinent

Vegetarianism in ancient India

India is a strange country. People do not kill

any living creatures, do not keep pigs and fowl,

and do not sell live cattle.

—Faxian, 4th/5th century CE

Chinese pilgrim to India

Most Indian religions have philosophical schools that forbid consumption of meat and Jainism institutes an outright ban on meat. Consequently, India is home to more vegetarians than any other country. About 30% of India's 1.2 billion population practices lacto vegetarianism. While many ancient Indian religions with vegetarian tenets persist throughout India and the Indian diaspora today, Buddhism and Buddhist vegetarian practices are now more widespread throughout other parts of Asia and manifest on other continents as well.

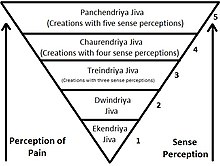

Jainism

Vegetarianism in Jainism is based on the principle of nonviolence (ahimsa, literally "non-injuring"). Vegetarianism is considered mandatory for everyone. Jains are either lacto-vegetarians or vegans. No use or consumption of products obtained from dead animals is allowed. Moreover, Jains try to avoid unnecessary injury to plants and suksma jiva (Sanskrit for 'subtle life forms'; minuscule organisms). The goal is to cause as little violence to living things as possible, hence they avoid eating roots, tubers such as potatoes, garlic and anything that involves uprooting (and thus eventually killing) a plant to obtain food.

Every act by which a person directly or indirectly supports killing or injury is seen as violence (hinsa), which creates harmful karma. The aim of ahimsa is to prevent the accumulation of such karma. Jains consider nonviolence to be the most essential religious duty for everyone (ahinsā paramo dharmaḥ, a statement often inscribed on Jain temples). Their scrupulous and thorough way of applying nonviolence to everyday activities, and especially to food, shapes their entire lives and is the most significant hallmark of Jain identity. A side effect of this strict discipline is the exercise of asceticism, which is strongly encouraged in Jainism for lay people as well as for monks and nuns.

Jains do not practice animal sacrifice as they consider all sentient beings to be equal.

Hinduism

While vegetarianism is an integral part of Hinduism, there are a wide variety of practices and beliefs that have changed over time. Some sects of Hindus do not observe vegetarianism, while an estimated 33% of all Hindus are vegetarians.

Nonviolence

The principle of nonviolence (ahimsa) applied to animals is connected with the intention to avoid negative karmic influences which result from violence. The suffering of all beings is believed to arise from craving and desire, conditioned by the karmic effects of both animal and human action. The violence of slaughtering animals for food, and its source in craving, reveal flesh eating as one mode in which humans enslave themselves to suffering. Hinduism holds that such influences affect the person who permits the slaughter of an animal, the person who kills it, the person who cuts it up, the person who buys or sells meat, the person who cooks it, the person who serves it up, and the person who eats it. They must all be considered the slayers of the animal. The question of religious duties towards the animals and of negative karma incurred from violence (himsa) against them is discussed in detail in Hindu scriptures and religious law books.

Hindu scriptures belong or refer to the Vedic period which lasted till about 500 BCE according to the chronological division by modern historians. In the historical Vedic religion, the predecessor of Hinduism, meat eating was not banned in principle, but was restricted by specific rules. Several highly authoritative scriptures bar violence against domestic animals except in the case of ritual sacrifice. This view is clearly expressed in the Mahabharata (3.199.11–12; 13.115; 13.116.26; 13.148.17), the Bhagavata Purana (11.5.13–14), and the Chandogya Upanishad (8.15.1). For instance, many Hindus point to the Mahabharata's maxim that "Nonviolence is the highest duty and the highest teaching," as advocating a vegetarian diet. The Mahabharata also states that adharma (sin) was born when creatures started to devour one another from want of food and that adharma always destroys every creature " It is also reflected in the Manu Smriti (5.27–44), a traditional Hindu law book (Dharmaśāstra). These texts strongly condemn the slaughter of animals and meat eating.

The Mahabharata (12.260; 13.115–116; 14.28) and the Manu Smriti (5.27–55) contain lengthy discussions about the legitimacy of ritual slaughter and subsequent consumption of the meat. In the Mahabharata both meat eaters and vegetarians present various arguments to substantiate their viewpoints. Apart from the debates about domestic animals, there is also a long discourse by a hunter in defence of hunting and meat eating. These texts show that both ritual slaughter and hunting were challenged by advocates of universal non-violence and their acceptability was doubtful and a matter of dispute.

Lingayats are strict vegetarians. Devout Lingayats do not consume beef, or meat of any kind including fish.

Modern day

In modern India, the food habits of Hindus vary according to their community or caste and according to regional traditions. Hindu vegetarians usually eschew eggs but consume milk and dairy products, so they are lacto-vegetarians.

According to a survey of 2006, vegetarianism is weak in coastal states and strong in landlocked northern and western states and among Brahmins in general, 85% of whom are lacto-vegetarians. In 2018, a study from Economic and Political Weekly showed that as few as one third of upper-caste Indians could be vegetarian.

Many coastal inhabitants are fish eaters. In particular, Bengali Hindus have romanticized fishermen and the consumption of fish through poetry, literature, and music.

Hindus who eat meat are encouraged to eat Jhatka meat.

Animal sacrifice in Hinduism

Animal sacrifice in Hinduism (sometimes known as Jhatka Bali) is the ritual killing of an animal in Hinduism.

The ritual sacrifice normally forms part of a festival to honour a Hindu god. For example, in Nepal the Hindu goddess Gadhimai, is honoured every five years with the slaughter of 250,000 animals. This practice was banned from 2015. Bali sacrifice today is common at the Sakta shrines of the Goddess Kali. However, animal sacrifice is illegal in India.

Buddhism

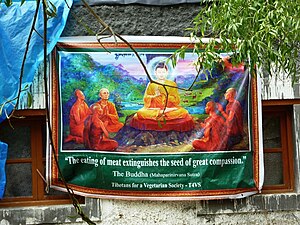

The First Precept prohibits Buddhists from killing people or animals. The matter of whether this forbids Buddhists from eating meat has long been a matter of debate, however, as vegetarianism is not a given in all schools of Buddhism.

The first Buddhist monks and nuns were forbidden from growing, storing, or cooking their own food. They relied entirely on the generosity of alms to feed themselves, and were not allowed to accept money to buy their own food. They could not make special dietary requests, and had to accept whatever food alms givers had available, including meat. Monks and nuns of the Theravada school of Buddhism, which predominates in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Burma, and Laos, still follow these strictures today.

These strictures were relaxed in China, Korea, Japan, and other countries that follow Mahayana Buddhism, where monasteries were in remote mountain areas and the distance to the nearest towns made daily alms rounds impractical. There, Buddhist monks and nuns could cultivate their own crops, store their own harvests, cook their own meals, and accept money to buy foodstuffs in the market.

According to the Vinaya Pitaka, when Devadatta urged the Buddha to make complete abstinence from meat compulsory, the Buddha refused, maintaining that "monks would have to accept whatever they found in their begging bowls, including meat, provided that they had not seen, had not heard, and had no reason to suspect that the animal had been killed so that the meat could be given to them". There were prohibitions on specific kinds of meat: meat from humans, meat from royal animals such as elephants or horses, meat from dogs, and meat from dangerous animals like snakes, lions, tigers, panthers, bears and hyenas.

On the other hand, certain Mahayana sutras strongly denounce the eating of meat. According to the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha revoked this permission to eat meat and warned of a Dark Age when false monks would claim that they were allowed meat. In the Lankavatara Sutra, a disciple of the Buddha named Mahamati asks "[Y]ou teach a doctrine that is flavoured with compassion. It is the teaching of the perfect Buddhas. And yet we eat meat nonetheless; we have not put an end to it." An entire chapter is devoted to the Buddha's response, wherein he lists a litany of spiritual, physical, mental, and emotional reasons why meat eating should be abjured. However, according to Suzuki (2004:211), this chapter on meat eating is a "later addition to the text....It is quite likely that meat-eating was practiced more or less among the earlier Buddhists, which was made a subject of severe criticism by their opponents. The Buddhists at the time of the Laṅkāvatāra did not like it, hence this addition in which an apologetic tone is noticeable." Phelps (2004:64–65) points to a passage in the Surangama Sutra which implies advocacy of "not just a vegetarian, but a vegan lifestyle"; however, numerous scholars over the centuries have concluded that the Śūraṅgama Sūtra is a forgery. Moreover, in the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the same sutra which records his retraction of permission to eat meat, the Buddha explicitly identifies as "beautiful foods" honey, milk, and cream, all of which are eschewed by vegans. However, in several other Mahayana scriptures, too (e.g., the Mahayana jatakas), the Buddha is seen clearly to indicate that meat-eating is undesirable and karmically unwholesome.

Some suggest that the rise of monasteries in Mahayana tradition to be a contributing factor in the emphasis on vegetarianism. In the monastery, food was prepared specifically for monks. In this context, large quantities of meat would have been specifically prepared (killed) for monks. Henceforth, when monks from the Indian geographical sphere of influence migrated to China from the year 65 CE on, they met followers who provided them with money instead of food. From those days onwards Chinese monastics, and others who came to inhabit northern countries, cultivated their own vegetable plots and bought food in the market. This remains the dominant practice in China, Vietnam, and part of Korean Mahayanan temples.

Mahayana lay Buddhists often eat vegetarian diets on the vegetarian dates (齋期). There are different arrangement of the dates, from several days to three months in each year, in some traditions, the celebration of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara's birthday, enlightenment and leaving home days hold the highest importance to be vegetarian.

In China, Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan, and their respective diaspora communities, monks and nuns are expected to abstain from meat and, traditionally, eggs and dairy, in addition to the fetid vegetables – traditionally garlic, Allium chinense, asafoetida, shallot, and Allium victorialis (victory onion or mountain leek), although in modern times this rule is often interpreted to include other vegetables of the onion genus, as well as coriander – this is called pure vegetarianism or veganism (純素, chúnsù). Pure vegetarianism or veganism is Indic in origin and is still practiced in India by some adherents of Dharmic religions such as Jainism and in the case of Hinduism, lacto-vegetarianism with the additional abstention of pungent or fetid vegetables.

In the modern Buddhist world, attitudes toward vegetarianism vary by location. In China and Vietnam, monks typically eat no meat, with other restrictions as well. In Japan or Korea, some schools do not eat meat, while most do. Theravadins in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia do not practice vegetarianism. All Buddhists, including monks, are allowed to practice vegetarianism if they wish to do so. Phelps (2004:147) states that "There are no accurate statistics, but I would guess—and it is only a guess—that worldwide about half of all Buddhists are vegetarian".

Sikhism

Followers of Sikhism do not have a preference for meat or vegetarian consumption. There are two views on initiated or "Amritdhari Sikhs" and meat consumption. "Amritdhari" Sikhs (i.e., those who follow the Sikh Rehat Maryada, the Official Sikh Code of Conduct) can eat meat (provided it is not Kutha meat). "Amritdharis" who belong to some Sikh sects (e.g., Akhand Kirtani Jatha, Damdami Taksal, Namdhari, Rarionwalay, etc.) are vehemently against the consumption of meat and eggs.

In the case of meat, the Sikh gurus have indicated their preference for a simple diet, which could include meat or not. Passages from the Guru Granth Sahib (the holy book of Sikhs, also known as the Adi Granth) say that fools argue over this issue. Guru Nanak said that overconsumption of food (Lobh, 'greed') involves a drain on the Earth's resources and thus on life. The tenth guru, Guru Gobind Singh, prohibited the Sikhs from the consumption of halal or Kutha (any ritually slaughtered meat) meat because of the Sikh belief that sacrificing an animal in the name of God is mere ritualism (something to be avoided).

Guru Nanak states that all living beings are connected. Even meat comes from the consumption of vegetables, and all forms of life are based on water.

O Pandit, you do not know where did flesh originate! It is water where life originated and it is water that sustains all life. It is water that produces grains, sugarcane, cotton and all forms of life.

— Guru Granth Sahib 1290

Sikhs who eat meat eat Jhatka meat.

Abrahamic religions

Judaic, Christian, and Muslim traditions (Abrahamic religions) all have strong connections to the Biblical ideal of the Garden of Eden, which includes references to a herbivore diet.[Genesis 1:29–31, Isaiah 11:6–9] While vegetarianism has not traditionally been viewed as mainstream in these traditions, some Jews, Christians, and Muslims practice and advocate vegetarianism.

Judaism

Though Jewish vegetarianism is not often viewed as mainstream, a number of Jews have argued for Jewish vegetarianism. Medieval rabbis such as Joseph Albo and Isaac Arama regarded vegetarianism as a moral ideal, and a number of modern Jewish groups and Jewish religious and cultural authorities have promoted vegetarianism. Groups advocating for Jewish vegetarianism include Jewish Veg, a contemporary grassroots organization promoting veganism as "God's ideal diet", and the Shamayim V'Aretz Institute, which promotes a vegan diet in the Jewish community through animal welfare activism, kosher veganism, and Jewish spirituality. One source of advocacy for Jewish vegetarianism in Israel is Amirim, a vegetarian moshav (village).

Jewish Veg has named 75 contemporary rabbis who encourage veganism for all Jews, including Jonathan Wittenberg, Daniel Sperber, David Wolpe, Nathan Lopes Cardozo, Kerry Olitzky, Shmuly Yanklowitz, Aryeh Cohen, Geoffrey Claussen, Rami M. Shapiro, David Rosen, Raysh Weiss, Elyse Goldstein, Shefa Gold, and Yonassan Gershom. Other rabbis who have promoted vegetarianism have included David Cohen, Shlomo Goren, Irving Greenberg, Asa Keisar, Jonathan Sacks, She'ar Yashuv Cohen, and Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog. Other notable advocates of Jewish vegetarianism include Franz Kafka, Roberta Kalechofsky, Richard H. Schwartz, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Jonathan Safran Foer, and Aaron S. Gross.

Jewish vegetarians often cite Jewish principles regarding animal welfare, environmental ethics, moral character, and health as reasons for adopting a vegetarian or vegan diet. Some Jews point to legal principles including Bal tashkhit (the law which prohibits waste) and Tza'ar ba'alei hayyim (the injunction not to cause 'pain to living creatures'). Many Jewish vegetarians are particularly concerned about cruel practices in factory farms and high-speed, mechanized slaughterhouses. Jonathan Safran Foer has raised these concerns in the short documentary film If This Is Kosher..., responding to what he considers abuses within the kosher meat industry.

Some Jewish vegetarians have pointed out that Adam and Eve were not allowed to eat meat. Genesis 1:29 states "And God said: Behold, I have given you every herb yielding seed which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree that has seed-yielding fruit—to you it shall be for food," indicating that God's original plan was for mankind to be vegan.· According to some opinions, the whole world will again be vegetarian in the Messianic era, and not eating meat brings the world closer to that ideal. As the ideal images of the Torah are vegetarian, one may see the laws of kashrut as actually designed to wean Jews away from meat eating and to move them toward the vegetarian ideal.

Christianity

Within Eastern Christianity, vegetarianism is practiced as part of fasting during the Great Lent (although shellfish and other non-vertebrate products are generally considered acceptable during some periods of this time); vegan fasting is particularly common in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodox Churches, such as the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, which generally fasts 210 days out of the year. This tradition greatly influenced the cuisine of Ethiopia.

Some Christian groups, such as Seventh-day Adventists, the Christian Vegetarian Association and Christian anarchists, take a literal interpretation of the Biblical prophecies of universal vegetarianism (or veganism)[Genesis 1:29–1:31, Isaiah 11:6–11:9, Isaiah 65:25] and encourage these practices as preferred lifestyles or as a tool to reject the commodity status of animals and the use of animal products for any purpose, although some of them say it is not required. Other groups point instead to allegedly explicit prophecies of temple sacrifices in the Messianic Kingdom, e.g. Ezekiel 46:12, where so-called peace offerings and so-called freewill offerings are said that will be offered, and Leviticus 7:15–20 where it states that such offerings are eaten, what may contradict the very purpose of Jesus' purportedly sufficient atonement.

Several Christian monastic groups, including the Desert Fathers, Trappists, Benedictines, Cistercians and Carthusians, all of the Orthodox monks and also Christian esoteric groups, such as the Rosicrucian Fellowship, have encouraged pescatarianism.

The Bible Christian Church, a Christian vegetarian sect founded by Reverend William Cowherd in 1809, were one of the philosophical forerunners of the Vegetarian Society. Cowherd encouraged members to abstain from eating of meat as a form of temperance.

Some Christian vegetarians, such as Keith Akers, argue that Jesus himself was a vegetarian. Akers argues that Jesus was influenced by the Essenes, an ascetic Jewish sect. The present academic consensus is that Jesus was not an Essene. There is no historical record of Jesus' precise attitudes to animals, but there is a strand in his ethical teaching about the primacy of mercy to the weak, the powerless and the oppressed, which Walters and Portmess argue can also refer to captive animals.

Other, more recent Christians movements, such as Sarx and CreatureKind, do not maintain that Jesus himself was a vegetarian, but instead argue that many practices which occur in the contemporary industrialized farming system, such as the mass culling of day-old male-chicks in the egg industry, are incompatible with the life of peace and love to which Jesus called his followers.

Islam

Islam explicitly prohibits eating of some kinds of meat, especially pork. However, one of the most important Islamic celebrations, Eid al-Adha, involves animal sacrifices (Udhiya). Muslims who can afford to do so sacrifice domestic animals (usually sheep, but also camels, cows, and goats). According to the Quran, a large portion of the meat has to be given towards the poor and hungry, and every effort is to be made to see that no impoverished Muslim is left without sacrificial food during the days of feasts like Eid-ul-Adha. On the other hand, Udhiya is only a sunnah and is not obligatory: even caliphs have used non-animal means of sacrifice for Eid.

Certain Islamic orders are mainly vegetarian; many Sufis maintain a vegetarian diet. Some Muslims in Indonesia think that being a vegetarian for reasons other than health is un-Islamic and it is a form of emulation of the infidels (tashabbuh bil kuffar). On the other hand, the Rishi order in Kashmir were historically described as abstaining from meat consumption.

The prophet Muhammad, however, was strongly against the frequent consumption of meat and, for his part, was said to subsist mainly on a diet of dates and barley.

Vegetarianism has been practiced by some influential Muslims including the Iraqi theologian, female mystic and poet Rabia of Basra, who died in the year 801, the Sufi mystic and poet Rumi and the Sri Lankan Sufi master Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, who established The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship of North America in Philadelphia. The former Indian president Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam was also famously a vegetarian.

In January 1996, The International Vegetarian Union announced the formation of the Muslim Vegetarian/Vegan Society. There is also a Vegan Muslim Initiative, founded 2017. They encourage Muslims to try a vegan diet during Ramadan, making it a "Veganadan".

Proponents of vegetarianism in Islam have pointed to the teachings in the Quran and the Hadith which instruct kindness and compassion towards animals as well as avoiding excess:

"Transgress not in the balance, and weigh with justice, and skimp not in the balance...earth, He set it down for all beings"

– Surrah Ar-Rahman 55:8–10

"Whoever is kind to the creatures of God is kind to himself."

– Hadith: Bukhari"A good deed done to an animal is as meritorious as a good deed done to a human being, while an act of cruelty to an animal is as bad as an act of cruelty to a human being."

– Hadith: Mishkat al-Masabih; Book 6; Chapter 7, 8:178"O sons of wisdom, do not turn your stomachs into graveyards for animals."

– Hadith: Fayd al-Qadīr Sharh al-Jami' as-Saghīr 2/52"Beware of meat, for meat can be as addictive as wine"

– Hadith: al-Muwaṭṭa’ 1742

Rastafari

Rastafari generally follow a diet called "I-tal", which eschews the eating of food that has been artificially preserved, flavoured, or chemically altered in any way. Some Rastafari consider it to also forbid the eating of meat but the majority will not eat pork at the very least, considering it unclean.

Baháʼí Faith

While there are no dietary restrictions in the Baháʼí Faith, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, noted that a vegetarian diet consisting of fruits and grains was desirable, except for people with a weak constitution or those that are sick. He stated that there are no requirements that Baháʼís become vegetarian, but that a future society would gradually become vegetarian. 'Abdu'l-Bahá also stated that killing animals was somewhat contrary to compassion. While Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Baháʼí Faith in the first half of the 20th century, stated that a purely vegetarian diet would be preferable since it avoided killing animals, both he and the Universal House of Justice (the governing body of the Baháʼís) have stated that these teachings do not constitute a Baháʼí practice and that Baháʼís can choose to eat whatever they wish, but to be respectful of others' beliefs.

Other religions

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was a religion established by the Iranian named Mani during the Sassanian Empire. The religion prohibited slaughtering or eating animals.

Zoroastrianism

Mazdakism, a sect of Zoroastrianism, explicitly promoted vegetarianism.

One of the main precepts in Zoroastrianism is respect and kindness towards all living things and condemnation of cruelty against animals.

The Shahnameh states that the evil king of Persia, Zohak, was first taught eating meat by the evil one who came to him in the guise of a cook. This was the start of an age of great evil for Persia. Prior to this, in the Golden age of mankind in the days of the great Aryan Kings, man did not eat meat.

The Pahlavi scriptures state that in the final stages of the world, when the final Saviour Saoshyant arrives, man will become more spiritual and gradually give up meat eating.

Vegetarianism is stated to be the future state of the world in Pahlavi scriptures – Atrupat-e Emetan in Iran in Denkard Book VI requested all Zoroastrians to be vegetarians:

"ku.san enez a-on ku urwar xwarishn bawed shmah mardoman ku derziwishn bawed, ud az tan i gospand pahrezed, ce amar was, e.g. Ohrmaz i xwaday hay.yarih i gospand ray urwar was dad."

Meaning: They hold this also: Be plant eaters (urwar xwarishn) (i.e. vegetarian), O you, men, so that you may live long. Keep away from the body of cattle (tan i gospand), and deeply reckon that Ohrmazd, the Lord has created plants in great number for helping cattle (and men)."

Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam promotes vegetarianism deeming it the "most healthful and virtuous way to eat".

Taoism

In Chinese societies, "simple eating" (素食 Mandarin: sù shí) refers to a particular restricted diet associated with Taoist monks, and sometimes practiced by members of the general population during Taoist festivals and fasting days. It is similar to Chinese Buddhist vegetarianism. Varying levels of abstinence among Taoists and Taoist-influenced people include veganism, veganism without root vegetables, lacto-ovo vegetarianism, and pescetarianism. Taoist vegetarians also tend to abstain from alcohol and pungent vegetables such as garlic and onions during lenten days. Non-vegetarian Taoists sometimes abstain from beef and water buffalo meat for many cultural reasons.

Vegetarianism in the Taoist tradition is similar to that of Lent in the Christian tradition. While highly religious people such as monks may be vegetarian, vegan or pescetarian on a permanent basis, lay practitioners often eat vegetarian on the 1st (new moon), 8th, 14th, 18th, 23rd, 24th, 28th, 29th and 30th days of the lunar calendar. In accordance with their Buddhist peers, and because many people are both Taoist and Buddhist, they often also eat lenten on the 15th day (full moon). Taoist vegetarianism is similar to Chinese Buddhist vegetarianism, however, its roots reach to pre-Buddhist times. Believers historically abstained from animal products and alcohol before practicing Confucian, Taoist and Chinese folk religion rites.

It is referred to by the English word "vegetarian"; however, though it rejects meat, eggs, and milk, this diet may include oysters and oyster products or otherwise be pescetarian for some believers. Many lay Taoists who follow modern sects such as that of Yi Guan Dao or Master Ching Hai are vegan or strictly vegetarian.

Faithist/Oahspe

Oahspe(Meaning Sky, Earth and Spirit) is the doctrinal book of those who follow Faithism. The precepts for behavior can be found throughout the book which include" a herbivorous diet (vegan, vegetable food only), peaceful living (no warring or violence; pacifism), living a life of virtue, service to others, angelic assistance, spiritual communion, and communal living when it is feasible to do so. Freedom and responsibility are two themes reiterated throughout the text of Oahspe.

Neopaganism

There is no set teaching on vegetarianism within the diverse neopagan communities, however many do follow a vegetarian diet often connected to ecological concerns as well as the welfare and rights of animals. Vegetarian practitioners of Wicca will often see their standpoint as a natural extension of the Wiccan Rede. Organizations like SERV refer to the historic figures of Porphyry, Pythagoras and Iamblichus as sources for the Pagan view of vegetarianism. During the 1970s the publication Earth Religion News, focused on articles related to neopaganism and vegetarianism, it was edited by the author Herman Slater.

Meher Baba's teachings

The spiritual teacher Meher Baba recommended a vegetarian diet for his followers because he held that it helps one to avoid certain impurities: "Killing an animal for sport, pleasure or food means catching all its bad impressions, since the motive is selfish....Impressions are contagious. Eating meat is prohibited in many spiritual disciplines because therein the person catches the impressions of the animal, thus rendering himself more susceptible to lust and anger."