| Geographical range | Veracruz, |

|---|---|

| Period | Preclassic Era |

| Dates | c. 2,500 – 400 BCE |

| Type site | San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán |

| Major sites | La Venta, Tres Zapotes, Laguna de los Cerros |

| Preceded by | Archaic Mesoamerica |

| Followed by | Epi-Olmecs |

The Olmecs (/ˈɒlmɛks, ˈoʊl-/) were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derived in part from the neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque cultures.

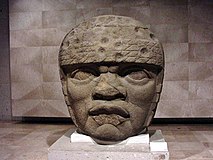

The Olmecs flourished during Mesoamerica's formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished since about 2500 BCE, but by 1600–1500 BCE, early Olmec culture had emerged, centered on the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán site near the coast in southeast Veracruz. They were the first Mesoamerican civilization, and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed. Among other "firsts", the Olmec appeared to practice ritual bloodletting and played the Mesoamerican ballgame, hallmarks of nearly all subsequent Mesoamerican societies. The aspect of the Olmecs most familiar now is their artwork, particularly the aptly named "colossal heads". The Olmec civilization was first defined through artifacts which collectors purchased on the pre-Columbian art market in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. Olmec artworks are considered among ancient America's most striking.

Etymology

The name 'Olmec' comes from the Nahuatl word for the Olmecs: Ōlmēcatl [oːlˈmeːkat͡ɬ] (singular) or Ōlmēcah [oːlˈmeːkaʔ] (plural). This word is composed of the two words ōlli [ˈoːlːi], meaning "natural rubber", and mēcatl [ˈmeːkat͡ɬ], meaning "people", so the word means "rubber people". Rubber was an important part of the ancient Mesoamerican ballgame.

Overview

The Olmec heartland is the area in the Gulf lowlands where it expanded after early development in Soconusco, Veracruz. This area is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills, ridges, and volcanoes. The Sierra de los Tuxtlas rises sharply in the north, along the Gulf of Mexico's Bay of Campeche. Here, the Olmec constructed permanent city-temple complexes at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. In this region, the first Mesoamerican civilization emerged and reigned from c. 1400–400 BCE.

Origins

The beginnings of Olmec civilization have traditionally been placed between 1400 and 1200 BCE. Past finds of Olmec remains ritually deposited at the shrine El Manatí near the triple archaeological sites known collectively as San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán moved this back to "at least" 1600–1500 BCE. It seems that the Olmec had their roots in early farming cultures of Tabasco, which began between 5100 BCE and 4600 BCE. These shared the same basic food crops and technologies of the later Olmec civilization.

What is today called Olmec first appeared fully within San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, where distinctive Olmec features occurred around 1400 BCE. The rise of civilization was assisted by the local ecology of well-watered alluvial soil, as well as by the transportation network provided by the Coatzacoalcos river basin. This environment may be compared to that of other ancient centers of civilization: the Nile, Indus, and Yellow River valleys and Mesopotamia. This highly productive environment encouraged a densely concentrated population, which in turn triggered the rise of an elite class. The elite class created the demand for the production of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts that define Olmec culture. Many of these luxury artifacts were made from materials such as jade, obsidian, and magnetite, which came from distant locations and suggest that early Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network in Mesoamerica. The source of the most valued jade was the Motagua River valley in eastern Guatemala, and Olmec obsidian has been traced to sources in the Guatemala highlands, such as El Chayal and San Martín Jilotepeque, or in Puebla, distances ranging from 200 to 400 km (120–250 miles) away, respectively.

The state of Guerrero, and in particular its early Mezcala culture, seem to have played an important role in the early history of Olmec culture. Olmec-style artifacts tend to appear earlier in some parts of Guerrero than in the Veracruz-Tabasco area. In particular, the relevant objects from the Amuco-Abelino site in Guerrero reveal dates as early as 1530 BCE. The city of Teopantecuanitlan in Guerrero is also relevant in this regard.

La Venta

The first Olmec center, San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 BCE at about the same time that La Venta rose to prominence. A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzo monuments also occurred c. 950s BCE, which may indicate an internal uprising or, less likely, an invasion. The latest thinking, however, is that environmental changes may have been responsible for this shift in Olmec centers, with certain important rivers changing course.

In any case, following the decline of San Lorenzo, La Venta became the most prominent Olmec center, lasting from 900 BCE until its abandonment around 400 BCE. La Venta sustained the Olmec cultural traditions with spectacular displays of power and wealth. The Great Pyramid was the largest Mesoamerican structure of its time. Even today, after 2500 years of erosion, it rises 34 m (112 ft) above the naturally flat landscape. Buried deep within La Venta lay opulent, labor-intensive "offerings" – 1000 tons of smooth serpentine blocks, large mosaic pavements, and at least 48 separate votive offerings of polished jade celts, pottery, figurines, and hematite mirrors.

Decline

Scholars have yet to determine the cause of the eventual extinction of the Olmec culture. Between 400 and 350 BCE, the population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, and the area was sparsely inhabited until the 19th century. According to archaeologists, this depopulation was probably the result of "very serious environmental changes that rendered the region unsuited for large groups of farmers", in particular changes to the riverine environment that the Olmec depended upon for agriculture, hunting and gathering, and transportation. These changes may have been triggered by tectonic upheavals or subsidence, or the siltation of rivers due to agricultural practices.

One theory for the considerable population drop during the Terminal Formative period is suggested by Santley and colleagues (Santley et al. 1997), who propose the relocation of settlements due to volcanism, instead of extinction. Volcanic eruptions during the Early, Late and Terminal Formative periods would have blanketed the lands and forced the Olmec to move their settlements.

Whatever the cause, within a few hundred years of the abandonment of the last Olmec cities, successor cultures became firmly established. The Tres Zapotes site, on the western edge of the Olmec heartland, continued to be occupied well past 400 BCE, but without the hallmarks of the Olmec culture. This post-Olmec culture, often labeled the Epi-Olmec, has features similar to those found at Izapa, some 550 kilometres (340 mi) to the southeast.

Artifacts

The Olmec culture was first defined as an art style, and this continues to be the hallmark of the culture. Wrought in a large number of media – jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone among others – much Olmec art, such as The Wrestler, is naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning. Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of which are seen in representations of werejaguars. In addition to making human and human-like subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animal portrayals.

While Olmec figurines are found abundantly in sites throughout the Formative Period, the stone monuments such as the colossal heads are the most recognizable feature of Olmec culture. These monuments can be divided into four classes:

- Colossal heads (which can be up to 3 m (10 ft) tall);

- Rectangular "altars" (more likely thrones) such as Altar 5 shown below;

- Free-standing in-the-round sculpture, such as the twins from El Azuzul or San Martín Pajapan Monument 1; and

- Stele, such as La Venta Monument 19 above. The stelae form was generally introduced later than the colossal heads, altars, or free-standing sculptures. Over time, the stele changed from simple representation of figures, such as Monument 19 or La Venta Stela 1, toward representations of historical events, particularly acts legitimizing rulers. This trend would culminate in post-Olmec monuments such as La Mojarra Stela 1, which combines images of rulers with script and calendar dates.

Colossal heads

The most recognized aspect of the Olmec civilization are the enormous helmeted heads. As no known pre-Columbian text explains them, these impressive monuments have been the subject of much speculation. Once theorized to be ballplayers, it is now generally accepted that these heads are portraits of rulers, perhaps dressed as ballplayers. Infused with individuality, no two heads are alike and the helmet-like headdresses are adorned with distinctive elements, suggesting personal or group symbols. Some have also speculated that Mesoamerican people believed that the soul, along with all of one's experiences and emotions, was contained inside the head.

Seventeen colossal heads have been unearthed to date.

| Site | Count | Designations |

|---|---|---|

| San Lorenzo | 10 | Colossal Heads 1 through 10 |

| La Venta | 4 | Monuments 1 through 4 |

| Tres Zapotes | 2 | Monuments A & Q |

| Rancho la Cobata | 1 | Monument 1 |

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Cobata head, at 3.4 m (11 ft) high, to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m (4 ft 10 in). Scholars calculate that the largest heads weigh between 25 and 55 tonnes (28 and 61 short tons).

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, found in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas. The Tres Zapotes heads, for example, were sculpted from basalt found at the summit of Cerro el Vigía, at the western end of the Tuxtlas. The San Lorenzo and La Venta heads, on the other hand, were probably carved from the basalt of Cerro Cintepec, on the southeastern side, perhaps at the nearby Llano del Jicaro workshop, and dragged or floated to their final destination dozens of miles away. It has been estimated that moving a colossal head required the efforts of 1,500 people for three to four months.

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variously mutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/or reburied. Some monuments, and at least two heads, were recycled or recarved, but it is not known whether this was simply due to the scarcity of stone or whether these actions had ritual or other connotations. Scholars believe that some mutilation had significance beyond mere destruction, but some scholars still do not rule out internal conflicts or, less likely, invasion as a factor.

The flat-faced, thick-lipped heads have caused some debate due to their resemblance to some African facial characteristics. Based on this comparison, some writers have said that the Olmecs were Africans who had emigrated to the New World. But, the vast majority of archaeologists and other Mesoamerican scholars reject claims of pre-Columbian contacts with Africa. Explanations for the facial features of the colossal heads include the possibility that the heads were carved in this manner due to the shallow space allowed on the basalt boulders. Others note that in addition to the broad noses and thick lips, the eyes of the heads often show the epicanthic fold, and that all these characteristics can still be found in modern Mesoamerican Indians. For instance, in the 1940s, the artist/art historian Miguel Covarrubias published a series of photos of Olmec artworks and of the faces of modern Mexican Indians with very similar facial characteristics. The African origin hypothesis assumes that Olmec carving was intended to be a representation of the inhabitants, an assumption that is hard to justify given the full corpus of representation in Olmec carving.

Ivan Van Sertima claimed that the seven braids on the Tres Zapotes head was an Ethiopian hair style, but he offered no evidence it was a contemporary style. The Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco has said that the Olmec braids do not resemble contemporary Egyptian or Nubian braids.

Richard Diehl wrote "There can be no doubt that the heads depict the American Indian physical type still seen on the streets of Soteapan, Acayucan, and other towns in the region."

Jade face masks

Another type of artifact is much smaller; hardstone carvings in jade of a face in a mask form. Jade is a particularly precious material, and it was used as a mark of rank by the ruling classes. By 1500 BCE early Olmec sculptors mastered the human form. This can be determined by wooden Olmec sculptures discovered in the swampy bogs of El Manati. Before radiocarbon dating could tell the exact age of Olmec pieces, archaeologists and art historians noticed the unique "Olmec-style" in a variety of artifacts.

Curators and scholars refer to "Olmec-style" face masks but, to date, no example has been recovered in an archaeologically controlled Olmec context. They have been recovered from sites of other cultures, including one deliberately deposited in the ceremonial altepetl (precinct) of Tenochtitlan in what is now Mexico City. The mask would presumably have been about 2000 years old when the Aztecs buried it, suggesting such masks were valued and collected as were Roman antiquities in Europe. The 'Olmec-style' refers to the combination of deep-set eyes, nostrils, and strong, slightly asymmetrical mouth. The "Olmec-style" also very distinctly combines facial features of both humans and jaguars. Olmec arts are strongly tied to the Olmec religion, which prominently featured jaguars. The Olmec people believed that in the distant past a race of werejaguars was made between the union of a jaguar and a woman. One werejaguar quality that can be found is the sharp cleft in the forehead of many supernatural beings in Olmec art. This sharp cleft is associated with the natural indented head of jaguars.

Ornamental mask; 10th century BCE; serpentine; height: 9.2 cm, width: 7.9 cm, depth: 3.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mask; 10th–6th century BCE; jadeite; height: 17.1 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mask; c. 900-500 BCE; jadeite; Dallas Museum of Art (Dallas, Texas, US)

Mask with cinnabar "tattoos"; c. 900-300 BCE; jadeite with cinnabar; Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, US)

Kunz axes

The Kunz axes (also known as "votive axes") are figures that represent werejaguars and were apparently used for rituals. In most cases, the head is half the total volume of the figure. All Kunz axes have flat noses and an open mouth. The name "Kunz" comes from George Frederick Kunz, an American mineralogist, who described a figure in 1890.

1200-400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

900-500 BCE; stone; Dallas Museum of Art (Texas, US)

12th–3rd century BCE; stone; height: 32.2 cm, width: 14 cm, depth: 11.5 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

800-400 BCE; serpentine, cinnabar; Dallas Museum of Art

Beyond the heartland

Olmec-style artifacts, designs, figurines, monuments and iconography have been found in the archaeological records of sites hundreds of kilometres outside the Olmec heartland. These sites include:

Central Mexico

Tlatilco and Tlapacoya, major centers of the Tlatilco culture in the Valley of Mexico, where artifacts include hollow baby-face motif figurines and Olmec designs on ceramics.

Chalcatzingo, in Valley of Morelos, central Mexico, which features Olmec-style monumental art and rock art with Olmec-style figures.

Also, in 2007, archaeologists unearthed Zazacatla, an Olmec-influenced city in Morelos. Located about 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Mexico City, Zazacatla covered about 2.5 square kilometres (1 sq mi) between 800 and 500 BCE.

Western Mexico

Teopantecuanitlan, in Guerrero, which features Olmec-style monumental art as well as city plans with distinctive Olmec features.

Also, the Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlán cave paintings feature Olmec designs and motifs.

Southern Mexico and Guatemala

Olmec influence is also seen at several sites in the Southern Maya area.

In Guatemala, sites showing probable Olmec influence include San Bartolo, Takalik Abaj and La Democracia.

Nature of interaction

Many theories have been advanced to account for the occurrence of Olmec influence far outside the heartland, including long-range trade by Olmec merchants, Olmec colonization of other regions, Olmec artisans travelling to other cities, conscious imitation of Olmec artistic styles by developing towns – some even suggest the prospect of Olmec military domination or that the Olmec iconography was actually developed outside the heartland.

The generally accepted, but by no means unanimous, interpretation is that the Olmec-style artifacts, in all sizes, became associated with elite status and were adopted by non-Olmec Formative Period chieftains in an effort to bolster their status.

Notable innovations

In addition to their influence with contemporaneous Mesoamerican cultures, as the first civilization in Mesoamerica, the Olmecs are credited, or speculatively credited, with many "firsts", including the bloodletting and perhaps human sacrifice, writing and epigraphy, and the invention of popcorn, zero and the Mesoamerican calendar, and the Mesoamerican ballgame, as well as perhaps the compass. Some researchers, including artist and art historian Miguel Covarrubias, even postulate that the Olmecs formulated the forerunners of many of the later Mesoamerican deities.

Bloodletting and sacrifice speculation

Although the archaeological record does not include explicit representation of Olmec bloodletting, researchers have found other evidence that the Olmec ritually practiced it. For example, numerous natural and ceramic stingray spikes and maguey thorns have been found at Olmec sites, and certain artifacts have been identified as bloodletters.

The argument that the Olmec instituted human sacrifice is significantly more speculative. No Olmec or Olmec-influenced sacrificial artifacts have yet been discovered; no Olmec or Olmec-influenced artwork unambiguously shows sacrificial victims (as do the danzante figures of Monte Albán) or scenes of human sacrifice (such as can be seen in the famous ballcourt mural from El Tajín).

At El Manatí, disarticulated skulls and femurs, as well as the complete skeletons of newborn or unborn children, have been discovered amidst the other offerings, leading to speculation concerning infant sacrifice. Scholars have not determined how the infants met their deaths. Some authors have associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp werejaguar babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (on the right) or Las Limas figure. Any definitive answer requires further findings.

Writing

The Olmec may have been the first civilization in the Western Hemisphere to develop a writing system. Symbols found in 2002 and 2006 date from 650 BCE and 900 BCE respectively, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing found so far, which dates from about 500 BCE.

The 2002 find at the San Andrés site shows a bird, speech scrolls, and glyphs that are similar to the later Maya script. Known as the Cascajal Block, and dated between 1100 BCE and 900 BCE, the 2006 find from a site near San Lorenzo shows a set of 62 symbols, 28 of which are unique, carved on a serpentine block. A large number of prominent archaeologists have hailed this find as the "earliest pre-Columbian writing". Others are skeptical because of the stone's singularity, the fact that it had been removed from any archaeological context, and because it bears no apparent resemblance to any other Mesoamerican writing system.

There are also well-documented later hieroglyphs known as the Isthmian script, and while there are some who believe that the Isthmian may represent a transitional script between an earlier Olmec writing system and the Maya script, the matter remains unsettled.

Mesoamerican Long Count calendar and invention of the zero concept

This is the second oldest Long Count date yet discovered. The numerals 7.16.6.16.18 translate to 3 September 32 BCE (Julian). The glyphs surrounding the date are one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script.

The Long Count calendar used by many subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations, as well as the concept of zero, may have been devised by the Olmecs. Because the six artifacts with the earliest Long Count calendar dates were all discovered outside the immediate Maya homeland, it is likely that this calendar predated the Maya and was possibly the invention of the Olmecs. Indeed, three of these six artifacts were found within the Olmec heartland. But an argument against an Olmec origin is the fact that the Olmec civilization had ended by the 4th century BCE, several centuries before the earliest known Long Count date artifact.

The Long Count calendar required the use of zero as a place-holder within its vigesimal (base-20) positional numeral system. A shell glyph –![]() – was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 BCE. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.

– was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 BCE. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.

Mesoamerican ballgame

The Olmec are strong candidates for originating the Mesoamerican ballgame so prevalent among later cultures of the region and used for recreational and religious purposes. A dozen rubber balls dating to 1600 BCE or earlier have been found in El Manatí, a bog 10 km (6 mi) east of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan. These balls predate the earliest ballcourt yet discovered at Paso de la Amada, c. 1400 BCE, although there is no certainty that they were used in the ballgame.

Ethnicity and language

While the actual ethno-linguistic affiliation of the Olmec remains unknown, various hypotheses have been put forward. For example, in 1968 Michael D. Coe speculated that the Olmec were Maya predecessors.

In 1976, linguists Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman published a paper in which they argued a core number of loanwords had apparently spread from a Mixe–Zoquean language into many other Mesoamerican languages. Campbell and Kaufman proposed that the presence of these core loanwords indicated that the Olmec – generally regarded as the first "highly civilized" Mesoamerican society – spoke a language ancestral to Mixe–Zoquean. The spread of this vocabulary particular to their culture accompanied the diffusion of other Olmec cultural and artistic traits that appears in the archaeological record of other Mesoamerican societies.

Mixe–Zoque specialist Søren Wichmann first critiqued this theory on the basis that most of the Mixe–Zoquean loans seemed to originate only from the Zoquean branch of the family. This implied the loanword transmission occurred in the period after the two branches of the language family split, placing the time of the borrowings outside of the Olmec period. However, new evidence has pushed back the proposed date for the split of Mixean and Zoquean languages to a period within the Olmec era. Based on this dating, the architectural and archaeological patterns and the particulars of the vocabulary loaned to other Mesoamerican languages from Mixe–Zoquean, Wichmann now suggests that the Olmecs of San Lorenzo spoke proto-Mixe and the Olmecs of La Venta spoke proto-Zoque.

At least the fact that the Mixe–Zoquean languages are still spoken in an area corresponding roughly to the Olmec heartland, and are historically known to have been spoken there, leads most scholars to assume that the Olmec spoke one or more Mixe–Zoquean languages.

Religion and mythology

Olmec religious activities were performed by a combination of rulers, full-time priests, and shamans. The rulers seem to have been the most important religious figures, with their links to the Olmec deities or supernaturals providing legitimacy for their rule. There is also considerable evidence for shamans in the Olmec archaeological record, particularly in the so-called "transformation figures".

As Olmec mythology has left no documents comparable to the Popol Vuh from Maya mythology, any exposition of Olmec mythology must be based on interpretations of surviving monumental and portable art (such as the Señor de Las Limas statue at the Xalapa Museum), and comparisons with other Mesoamerican mythologies. Olmec art shows that such deities as Feathered Serpent and a rain supernatural were already in the Mesoamerican pantheon in Olmec times.

Social and political organization

Little is directly known about the societal or political structure of Olmec society. Although it is assumed by most researchers that the colossal heads and several other sculptures represent rulers, nothing has been found like the Maya stelae which name specific rulers and provide the dates of their rule.

Instead, archaeologists relied on the data that they had, such as large- and small-scale site surveys. These provided evidence of considerable centralization within the Olmec region, first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta – no other Olmec sites come close to these in terms of area or in the quantity and quality of architecture and sculpture.

This evidence of geographic and demographic centralization leads archaeologists to propose that Olmec society itself was hierarchical, concentrated first at San Lorenzo and then at La Venta, with an elite that was able to use their control over materials such as water and monumental stone to exert command and legitimize their regime.

Nonetheless, Olmec society is thought to lack many of the institutions of later civilizations, such as a standing army or priestly caste. And there is no evidence that San Lorenzo or La Venta controlled, even during their heyday, all of the Olmec heartland. There is some doubt, for example, that La Venta controlled even Arroyo Sonso, only some 35 km (22 mi) away. Studies of the Sierra de los Tuxtlas settlements, some 60 km (35 mi) away, indicate that this area was composed of more or less egalitarian communities outside the control of lowland centers.

Trade

The wide diffusion of Olmec artifacts and "Olmecoid" iconography throughout much of Mesoamerica indicates the existence of extensive long-distance trade networks. Exotic, prestigious and high-value materials such as greenstone and marine shell were moved in significant quantities across large distances. Some of the reasons for trade revolve around the lack of obsidian in the heartland. The Olmec used obsidian in many tools because worked edges were very sharp and durable. Most of the obsidian found has been traced back to Guatemala showing the extensive trade. While the Olmec were not the first in Mesoamerica to organize long-distance exchanges of goods, the Olmec period saw a significant expansion in interregional trade routes, more variety in material goods exchanged and a greater diversity in the sources from which the base materials were obtained.

Village life and diet

Despite their size and deliberate urban design, which was copied by other centers, San Lorenzo and La Venta were largely ceremonial centers, and the majority of the Olmec lived in villages similar to present-day villages and hamlets in Tabasco and Veracruz.

These villages were located on higher ground and consisted of several scattered houses. A modest temple may have been associated with the larger villages. The individual dwellings would consist of a house, an associated lean-to, and one or more storage pits (similar in function to a root cellar). A nearby garden was used for medicinal and cooking herbs and for smaller crops, such as the domesticated sunflower. Fruit trees, such as avocado or cacao, were probably available nearby.

Although the river banks were used to plant crops between flooding periods, the Olmecs probably also practiced slash-and-burn agriculture to clear the forests and shrubs, and to provide new fields once the old fields were exhausted. Fields were located outside the village, and were used for maize, beans, squash, cassava, and sweet potato. Based on archaeological studies of two villages in the Tuxtlas Mountains, it is known that maize cultivation became increasingly important to the Olmec over time, although the diet remained fairly diverse.

The fruits and vegetables were supplemented with fish, turtle, snake, and mollusks from the nearby rivers, and crabs and shellfish in the coastal areas. Birds were available as food sources, as were game including peccary, opossum, raccoon, rabbit, and in particular, deer. Despite the wide range of hunting and fishing available, midden surveys in San Lorenzo have found that the domesticated dog was the single most plentiful source of animal protein.

History of archaeological research

Olmec culture was unknown to historians until the mid-19th century. In 1869, the Mexican antiquarian traveller José Melgar y Serrano published a description of the first Olmec monument to have been found in situ. This monument – the colossal head now labelled Tres Zapotes Monument A – had been discovered in the late 1850s by a farm worker clearing forested land on a hacienda in Veracruz. Hearing about the curious find while travelling through the region, Melgar y Serrano first visited the site in 1862 to see for himself and complete the partially exposed sculpture's excavation. His description of the object, published several years later after further visits to the site, represents the earliest documented report of an artifact of what is now known as the Olmec culture.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Olmec artifacts such as the Kunz Axe (right) came to light and were subsequently recognized as belonging to a unique artistic tradition.

Frans Blom and Oliver La Farge made the first detailed descriptions of La Venta and San Martin Pajapan Monument 1 during their 1925 expedition. However, at this time, most archaeologists assumed the Olmec were contemporaneous with the Maya – even Blom and La Farge were, in their own words, "inclined to ascribe them to the Maya culture".

Matthew Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution conducted the first detailed scientific excavations of Olmec sites in the 1930s and 1940s. Stirling, along with art historian Miguel Covarrubias, became convinced that the Olmec predated most other known Mesoamerican civilizations.

In counterpoint to Stirling, Covarrubias, and Alfonso Caso, however, Mayanists J. Eric Thompson and Sylvanus Morley argued for Classic-era dates for the Olmec artifacts. The question of Olmec chronology came to a head at a 1942 Tuxtla Gutierrez conference, where Alfonso Caso declared that the Olmecs were the "mother culture" ("cultura madre") of Mesoamerica.

Shortly after the conference, radiocarbon dating proved the antiquity of the Olmec civilization, although the "mother culture" question generated considerable debate even 60 years later.

DNA

In the investigations of the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project at the sites of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote, several human burials from the Olmec period were found. The bone consistency in two of them allowed the study of their mitochondrial DNA to be carried out successfully, as part of an investigation that proposes the comparative analysis of the genetic information of the Olmecs with that obtained from subjects from other Mesoamerican societies under the advice of the specialists Dr. María de Lourdes Muñoz Moreno, Research Professor Department of Genetics and Molecular Biology Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (CINVESTAV-IPN), Mexico and Miguel Moreno Galeana, also from CINVESTAV-IPN. This pioneering study of mitochondrial DNA in 2018 was carried out on two Olmec individuals, one from San Lorenzo and the other from Loma del Zapote, resulted, in both cases, in the unequivocal presence of the distinctive mutations of the haplogroup A maternal lineage. They share the most abundant of the five mitochondrial haplogroups characteristic of the indigenous populations of the Americas: A, B, C, D and X.

Etymology

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl, the language of the Nahuas, and was the Aztec Empire term for the people who lived in the Gulf Lowlands in the 15th and 16th centuries, some 2000 years after the Olmec culture died out. The term "Rubber People" refers to the ancient practice, spanning from ancient Olmecs to Aztecs, of extracting latex from Castilla elastica, a rubber tree in the area. The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create rubber as early as 1600 BCE.

Early modern explorers and archaeologists, however, mistakenly applied the name "Olmec" to the rediscovered ruins and artifacts in the heartland decades before it was understood that these were not created by the people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec", but rather a culture that was 2000 years older. Despite the mistaken identity, the name has stuck.

It is not known what name the ancient Olmec used for themselves; some later Mesoamerican accounts seem to refer to the ancient Olmec as "Tamoanchan". A contemporary term sometimes used for the Olmec culture is tenocelome, meaning "mouth of the jaguar".

Alternative origin speculations

Partly because the Olmecs developed the first Mesoamerican civilization, and partly because little is known of them compared to, for example, the Maya or Aztec, a number of Olmec alternative origin speculations have been put forth. Although several of these speculations, particularly the theory that the Olmecs were of African origin popularized by Ivan Van Sertima's book They Came Before Columbus, have become well known within popular culture, they are not considered credible by the vast majority of Mesoamerican researchers and scientists, who discard them as pop-culture pseudo-science.

As of 2018, mitochondrial DNA study carried out on Olmec remains, one from San Lorenzo and the other from Loma del Zapote, resulted, in both cases, in the “unequivocal presence of the distinctive mutations of the “A” maternal lineage. That is, the origin of the Olmecs is not in Africa but in America, since they share the most abundant of the five mitochondrial haplogroups characteristic of the indigenous populations of our continent: A, B, C, D and X.”

Gallery

The "twins" from El Azuzul, 1200–900 BCE

Carved travertine vessel with an incised pattern, 12th–3rd century BCE

Three celts, Olmec ritual objects

Olmec style bottle, reputedly from Las Bocas, 1100–800 BCE

Olmec-style painting from the Juxtlahuaca cave

Olmec-style bas relief "El Rey" from Chalcatzingo