| Buddhist Crisis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||

Thích Quảng Đức's self-immolation | |||

| Date | May–November 1963 | ||

| Location | |||

| Resulted in | 1963 South Vietnamese coup

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

The Buddhist crisis (Vietnamese: Biến cố Phật giáo) was a period of political and religious tension in South Vietnam between May and November 1963, characterized by a series of repressive acts by the South Vietnamese government and a campaign of civil resistance, led mainly by Buddhist monks.

The crisis was precipitated by the shootings of nine unarmed civilians on May 8 in the central city of Huế who were protesting a ban of the Buddhist flag. The crisis ended with a coup in November 1963 by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), and the arrest and assassination of President Ngô Đình Diệm on November 2, 1963.

Background

In South Vietnam, a country where the Buddhist majority was estimated to comprise between 70 and 90 percent of the population in 1963, President Ngô Đình Diệm's pro-Catholic policies antagonized many Buddhists. A member of the Catholic minority, Diệm headed a government biased towards Catholics in public service and military promotions, as well as in the allocation of land, business favors, and tax concessions. Diệm once told a high-ranking officer, forgetting that he was a Buddhist, "Put your Catholic officers in sensitive places. They can be trusted." Many ARVN officers converted to Catholicism in the belief that their career prospects depended on it, and many were refused promotion if they did not do so. Additionally, the distribution of firearms to village self-defense militias intended to repel Viet Cong guerrillas was done so that weapons were only given to Catholics. Some Catholic priests ran private armies while forced conversions, looting, shelling and demolition of pagodas occurred in some areas. Several Buddhist villages converted en masse to receive aid and to avoid forced resettlement by Diệm's regime.

The Catholic Church was the largest landowner in the country, and the "private" status that was imposed on Buddhism by the French, which required official permission to conduct public activities, was not repealed by Diệm. The land owned by the church was exempt from land reform, and Catholics were also de facto exempt from the corvée labor that the government obliged all other citizens to perform; public spending was disproportionately distributed to Catholic majority villages. Under Diệm, the Catholic Church enjoyed special exemptions in property acquisition, and in 1959, he dedicated the country to the Virgin Mary. The Vatican flag was regularly flown at major public events in South Vietnam. Earlier in January 1956, Diệm enacted Order 46 which permitted "Individuals considered dangerous to the national defense and common security [to] be confined by executive order, to a concentration camp." This order was used against dissenting Buddhists. The infamous action later caused anger inside its people, with lend to some of the minority supported or joined The Liberation Army of South Vietnam.

Events

May 1963

A rarely enforced 1958 law—known as Decree Number 10—was invoked in May 1963 to prohibit the display of religious flags. This disallowed the flying of the Buddhist flag on Vesak, the birthday of Gautama Buddha. The application of the law caused indignation among Buddhists on the eve of the most important religious festival of the year, as a week earlier Catholics had been encouraged to display Vatican flags at a government-sponsored celebration for Diệm's brother, Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục, the most senior Catholic cleric in the country. On May 8, in Huế, a crowd of Buddhists protested against the ban on the Buddhist flag. The police and army broke up the demonstration by firing guns at and throwing grenades into the gathering, leaving nine dead.

In response to the shootings in Huế, Buddhist leader Thích Trí Quang proclaimed a five-point "manifesto of the monks" that demanded freedom to fly the Buddhist flag, religious equality between Buddhists and Catholics, compensation for the victims' families, an end to arbitrary arrests, and punishment of the officials responsible. The request was formalized on 13 May, and talks began on 15 May.

Diệm denied governmental responsibility for the incident. Instead, the president blamed the Viet Cong for the event. Diệm's Secretary of State Nguyen Dinh Thuan accused the Viet Cong of exploiting Buddhist unrest and declared that Diệm could not make concessions without fueling further demands. The Vietnam Press, a pro-Diệm newspaper, published a government declaration confirming the existence of religious freedom and emphasizing the supremacy of the country's flag. Diệm's National Assembly affirmed this statement, but this did not placate the Buddhists. In one meeting, Diệm labeled the Buddhists "damn fools" for demanding something that according to him, they already enjoyed. The government press release detailing the meeting also used the expression "damn fools". On May 18, President Diệm agreed a modest compensation package of US$7000 for the families of the victims of the shootings in Huế. Diệm also agreed to dismiss those responsible for the shootings, but on the grounds that the officials had failed to maintain order, rather than any responsibility for the deaths of the protesters. He resolutely continued to blame the Viet Cong.

On May 30, more than 500 monks demonstrated in front of the National Assembly in Saigon. The Buddhists had evaded a ban on public assembly by hiring four buses, packing them with monks, and closing the blinds. They drove around the city until the convoy stopped at the designated time and the monks disembarked. This was the first time an open protest had been held in Saigon against Diệm in his eight years of rule. They unfurled banners and sat down for four hours before disbanding and returning to the pagodas to begin a nationwide 48-hour hunger strike organized by the Buddhist patriarch Thich Tinh Khiet.

June 1963

On June 1, Diệm's authorities announced the dismissal of the three major officials involved in the Huế incident: the provincial chief and his deputy, and the government delegate for the Central Region of Vietnam. The stated reason was that they had failed to maintain order. By this time, the situation appeared to be beyond reconciliation.

On June 3, amid nationwide protests in Saigon and other cities, Vietnamese police and ARVN troops poured chemicals on the heads of praying Buddhist protestors in Huế outside Từ Đàm Pagoda. Sixty-seven people were hospitalized and the United States privately threatened to withdraw aid.

Diệm responded to the controversy of the chemical attacks by agreeing to formal talks with the Buddhist leaders. He appointed a three-member Interministerial Committee, which included Vice President Nguyễn Ngọc Thơ as chairman, Thuan, and Interior Minister Bui Van Luong. The first meeting with Buddhist leaders took place two days after the attacks and one of the issues discussed was the standoff in Huế, and the cessation of protests if religious equality was implemented. Diệm appeared to soften his line, at least in public, in an address on 7 June when he said that some of the tensions were due to his officials lacking "sufficient comprehension and sensitivity" although there was no direct admission of fault regarding any of the violence in Huế since the start of the Buddhist crisis.

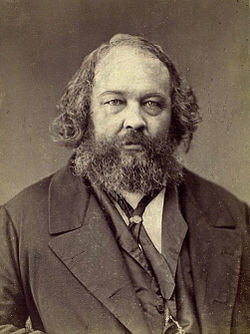

On June 11, Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức burned himself to death at a busy Saigon road intersection in protest against Diệm's policies.

In response to Buddhist self-immolation as a form of protest, Madame Nhu—the de facto First Lady of South Vietnam at the time (and the wife of Ngô Đình Nhu, who was the brother and chief advisor to Diệm)—said "Let them burn and we shall clap our hands", and "if the Buddhists wish to have another barbecue, I will be glad to supply the gasoline and a match."

Acting US Ambassador William Trueheart warned that without meaningful concessions, the US would publicly repudiate Diệm's regime. Diệm said that such a move would scupper the negotiations. On June 14, Diệm's committee met with the Buddhists, who lobbied for Diệm to immediately amend Decree Number 10 by presidential decree as allowed in the constitution, rather than wait for the National Assembly to do so. The National Assembly had announced a committee would be established on June 12 to deal with the issue. Trueheart recommended that the Interministerial Committee accept the Buddhist's position in a "spirit of amity" and then clarify the details at a later point. During the negotiations, Thích Tịnh Khiết issued a nationwide plea to urge Buddhists to avoid any actions that could endanger the talks while Diệm ordered government officials to remove all barriers around the temples.

On 16 June, an agreement between the committee and the Buddhists was reached. An agreement had been reached pertaining to all five demands, although the terms were vague. Diệm claimed it contained nothing that he had not already accepted. The "Joint Communique" asserted that the national flag "should always be respected and be put at its appropriate place". The National Assembly would consult with religious groups in an effort to remove them "from the regulations of Ordinance No. 10" and to establish new guidelines appropriate to their religious activities. In the meantime the government committee promised a loose application of the regulation. It also promised leniency in the censorship of Buddhist literature and prayer books and the granting of permits to construct Buddhist pagodas, schools and charitable institutions.

Both sides agreed to form an investigative committee to "re-examine" the Buddhist grievances and Diệm agreed to grant a full amnesty to all Buddhists who had protested against the government. The agreement stated the "normal and purely religious activity" could go unhindered without the need for government permission in pagodas or the headquarters of the General Association of Buddhists. Diệm promised an inquiry into the Huế shootings and punishment for any found guilty, although it denied government involvement. In an attempt to save face, Diệm signed the agreement directly under a paragraph declaring that "the articles written in this joint communiqué have been approved in principle by me from the beginning", which he added with his own handwriting, thereby implying that he had nothing to concede.

The Joint Communiqué was presented to the press on 16 June and Thích Tịnh Khiết thanked Diệm and exhorted the Buddhist community to work with the government. He expressed his "conviction that the joint communiqué will inaugurate a new era and that ... no erroneous action from whatever quarter will occur again." He declared that the protest movement was over, and called on Buddhists to return to their normal lives and pray for the success of the agreement. However, some younger monks were disappointed with the result of the negotiations feeling that Diem's regime had not been made accountable.

Trueheart was skeptical about its implementation, privately reporting that if Diệm did not follow through, the US should look for alternative leadership options. The troubles had become a public relations issue for Diem beyond his country, with speculation about a US-Diệm rift being discussed in American newspapers following the self-immolation. The New York Times ran a front page headline on 14 June, citing leaked government information that diplomats had privately attacked Diem. It also reported that General Paul Harkins, the head of the US advisory mission in South Vietnam, ordered his men not to assist ARVN units that were taking action against demonstrators. The US at the time considered telling Vice President Tho that they would support him replacing Diem as President. This occurred at the same time as the surfacing of rumours that Republic of Vietnam Air Force Chief of Staff Lieutenant Colonel Đỗ Khắc Mai had begun gauging support among his colleagues for a coup.

The agreement was put in doubt by an incident outside Xá Lợi Pagoda the following day. A crowd of around 2,000 people were confronted by police who persisted in ringing the pagoda despite the agreement. A riot eventually broke out and police attacked the crowd with tear gas, fire hoses, clubs, and gunfire. One protester was killed and scores more injured. Moderates from both sides urged calm while some government officials blamed "extremist elements". An Associated Press story described the riot as "the most violent anti-Government outburst in South Vietnam in years". Furthermore, many protesters remained in jail contrary to the terms of the Joint Communique. The crisis deepened as more Buddhists began calling for a change of government and younger monks such as Thích Trí Quang came to the forefront, blaming Diệm for the ongoing impasse. Due to the failure of the agreement to produce the desired results, older and more senior monks, who were more moderate, saw their prestige diminished, and the younger, more assertive monks began to take on a more prominent role in Buddhist politics.

Thich Tinh Khiet sent Diệm a letter after the funeral of Thích Quảng Đức, noting the government was not observing the agreement and that the condition of Buddhists in South Vietnam had deteriorated. Tho denied the allegation, and Ngô Đình Nhu told a reporter: "If anyone is oppressed in this affair, it is the government which has been constantly attacked and whose mouth has been shut with Scotch tape." He criticised the agreements through his Republican Youth organization, calling on the population to "resist the indirections [sic] of superstition and fanaticism" and warned against "communists who may abuse the Joint Communique". At the same time, Nhu issued a secret memorandum to the Republican Youth, calling on them to lobby the government to reject the agreement, and calling the Buddhists "rebels" and "communists". Nhu continued to disparage the Buddhists through his English-language mouthpiece, the Times of Vietnam, whose editorial bent was usually taken to be the Ngô family's own personal opinions.

A US State Department report concluded that the religious disquiet was not fomented by communist elements. In the meantime the government had quietly informed local officials that the agreements were a "tactical retreat" to buy time before decisive putting down the Buddhist movement. Diệm's regime stalled on implementing the release of Buddhists who had been imprisoned for protesting against it. This led to a discussion within the US government to push for the removal of the Nhus, who were regarded as the extremist influence over Diệm, from power.

The Buddhists were becoming increasingly skeptical of government intentions. They had received information that suggested that the agreement was just a governmental tactic to buy time and wait for the popular anger to die down, before Diệm would arrest the leading Buddhist monks. They began to step up the production of critical pamphlets and began translating articles critical of Diệm in the Western media to distribute to the public. As promises continued to fail to materialise, the demonstrations at Xá Lợi and elsewhere continued to grow.

July 1963

In July, Diệm's government continued to attack the Buddhists. It accused Thích Quảng Đức of having been drugged before being set alight. Tho speculated that the Viet Cong had infiltrated the Buddhists and converted them into a political organization. Interior Minister Luong alleged that cabinet ministers had received death threats. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. was announced as the new US ambassador effective in late August, replacing Frederick Nolting, who was considered too close to Diệm.

On July 7, 1963, the secret police of Ngô Đình Nhu attacked a group of journalists from the United States who were covering Buddhist protests on the ninth anniversary of Diem's rise to power. Peter Arnett of the Associated Press (AP) was punched in the nose, but the quarrel quickly ended after David Halberstam of The New York Times, being much taller than Nhu's men, counterattacked and caused the secret police to retreat. Arnett and his colleague, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and photographer Malcolm Browne, were later accosted by police at their office and taken away for questioning on suspicion of attacking police officers. In the end, Diem agreed to have the charges against Browne and Arnett dropped after intervention from the US Embassy.

On the same day, Diem publicly claimed that the "problems raised by the General Association of Buddhists have just been settled." He reinforced perceptions that he was out of touch by attributing any lingering problems to the "underground intervention of international red agents and Communist fellow travelers who in collusion with fascist ideologues disguised as democrats were surreptitiously seeking to revive and rekindle disunity at home while arousing public opinions against us abroad."

August 1963

On Sunday, August 18, the Buddhists staged a mass protest at Xá Lợi Pagoda, Saigon's largest, attracting around 15,000 people, undeterred by rain. The attendance was approximately three times higher than that at the previous Sunday's rally. The event lasted for several hours, as speeches by the monks interspersed religious ceremonies. A Vietnamese journalist said that it was the only emotional public gathering in South Vietnam since Diem's rise to power almost a decade earlier. David Halberstam of The New York Times speculated that by not exploiting the large crowd by staging a protest march towards Gia Long Palace or other government buildings, the Buddhists were saving their biggest demonstration for the scheduled arrival of new US ambassador, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the following week. As a government attack on Xa Loi was anticipated, Halberstam concluded that the Buddhists were playing "a fast and dangerous game". He wrote that "the Buddhists themselves appeared to be at least as much aware of all the developments, and their protest seemed to have a mounting intensity".

On the evening of August 18, ten senior ARVN generals met to discuss the situation and decided that martial law needed to be imposed. On August 20, Nhu summoned seven of the generals to Gia Long Palace for consultation. They presented their request to impose martial law and discussed dispersion of the monks. Nhu sent the generals to see Diệm. The president listened to the group of seven, led by General Trần Văn Đôn. Đôn claimed that communists had infiltrated the monks at Xá Lợi Pagoda and warned that ARVN morale was deteriorating because of the civil unrest. He claimed that it was possible that the Buddhists could assemble a crowd to march on Gia Long Palace. Hearing this, Diệm agreed to declare martial law effective the next day, without consulting his cabinet. Troops were ordered into Saigon to occupy strategic points. Đôn was appointed as the acting Chief of the Armed Forces in the place of General Lê Văn Tỵ, who was abroad having medical treatment. Đôn noted that Diệm was apparently concerned with the welfare of the monks, telling the generals that he did not want any of them hurt. The martial law orders were authorized with the signature of Đôn, who had no idea that military action was to occur in the early hours of August 21 without his knowledge.

Shortly after midnight on August 21, on the instructions of Nhu, ARVN Special Forces troops under Colonel Lê Quang Tung executed a series of synchronized attacks on the Buddhist pagodas in South Vietnam. Over 1400 Buddhists were arrested. The number killed or "disappeared" is estimated to be in the hundreds. The most prominent of the pagodas raided was that of Xá Lợi, which had become the rallying point for Buddhists from the countryside. The troops vandalized the main altar and managed to confiscate the intact charred heart of Thích Quảng Đức, the monk who had self-immolated in protest against the policies of the regime. The Buddhists managed to escape with a receptacle holding the remainder of his ashes. Two monks jumped the back wall of the pagoda into the grounds of the adjoining US Aid Mission, where they were given asylum. Thich Tinh Khiet, the 80-year-old Buddhist patriarch, was seized and taken to a military hospital on the outskirts of Saigon. The commander of the ARVN III Corps, Tôn Thất Đính announced military control over Saigon, canceling all commercial flights into the city and instituting press censorship.

Once the US government realized the truth about who was behind the raids, they reacted with disapproval towards the Diệm regime. The US had pursued a policy of quietly and privately advising the Ngos to reconcile with the Buddhists while publicly supporting the alliance, but following the attacks, this route was regarded as untenable. Furthermore, the attacks were carried out by US-trained Special Forces personnel funded by the CIA, and presented incoming Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., with a fait accompli. The state department issued a statement declaring that the raids were a "direct violation" of the promise to pursue "a policy of reconciliation".

On August 24, the Kennedy administration sent Cable 243 to Lodge at the embassy in Saigon, marking a change in US policy. The message advised Lodge to seek the removal of Nhu from power, and to look for alternative leadership options if Diem refused to heed American pressure for reform. As the probability of Diệm's sidelining Nhu and his wife was seen as virtually nil, the message effectively meant the fomenting of a coup. The Voice of America also broadcast a statement blaming Nhu for the raids and absolving the army of responsibility.

September 1963

After the events of August, Diệm's regime became a major preoccupation of the Kennedy administration and a fact-finding mission was launched. The stated purpose of the expedition was to investigate the progress of the war by South Vietnam and their US military advisers against the Viet Cong insurgency. The Krulak Mendenhall mission was led by Victor Krulak and Joseph Mendenhall. Krulak was a major general in the United States Marine Corps, while Mendenhall was a senior foreign service officer experienced in dealing with Vietnamese affairs. The trip lasted four days.

In their submissions to the United States National Security Council (NSC), Krulak presented an extremely optimistic report on the progress of the war, while Mendenhall presented a very bleak picture of military failure and public discontent. Krulak disregarded the effects of popular discontent in combating the Viet Cong. The general felt that the Vietnamese soldiers' efforts in the field would not be affected by the public's unease with Diệm's policies. Mendenhall focused on gauging the sentiment of urban-based Vietnamese and concluded that Diệm's policies increased the possibility of religious civil war. Mendenhall said that Diệm's policies were causing the South Vietnamese to believe that life under the Viet Cong would improve the quality of their lives.

The divergent reports led US President John F. Kennedy to famously ask his two advisers, "The two of you did visit the same country, didn't you?"

The inconclusive report was the subject of bitter and personal debate among Kennedy's senior advisers. Various courses of action towards Vietnam were discussed, such as fostering a regime change or taking a series of selective measures designed to cripple the influence of the Nhus, who were seen as the major causes of the political problems in South Vietnam.

The disparate reports of Krulak and Mendenhall resulted in a follow-up mission, the McNamara-Taylor mission.