The issue of slavery was historically treated with concern by the Catholic Church. Throughout most of human history, slavery has been practiced and accepted by many cultures and religions around the world, including ancient Rome. Certain passages in the Old Testament sanctioned forms of temporal slavery as means to pay a debt. After the legalization of Christianity under the Roman empire, there was a growing sentiment that many kinds of slavery were not compatible with Christian conceptions of charity and justice; some argued against all forms of slavery while others, including the influential Thomas Aquinas, argued the case for slavery subject to certain restrictions. The Christian West did succeed in almost entirely enforcing that a free Christian could not be enslaved, for example when a captive in war. However, this itself was subject to continual improvement and was not consistently applied throughout history. The Middle Ages also witnessed the emergence of orders of monks such as the Mercedarians who were founded for the purpose of ransoming Christian slaves. By the end of the Medieval period, enslavement of Christians had been largely abolished throughout Europe although enslavement of non-Christians remained permissible and had seen a revival in Spain and Portugal. The permissibility of slavery remained a subject of debate within the Church for centuries, with several Popes issuing bulls on the issue, such as Sublimis Deus.

By the 1800s, the Church reached relative consensus in favor of condemning chattel slavery and praising its abolition.

Historical overview

After 313 CE, when Constantine legalized Christianity within the Roman Empire, the teachings of the Church concerning charity and justice began influencing Roman laws and policies. Pope Callixtus I (bishop of Rome 218–222 CE) had been a slave in his youth. Slavery decreased with multiple abolition movements in the late 5th century.

Theologians tried to address this issue over the centuries. The Middle Ages witnessed the emergence of groups like the Mercedarians, who were founded for the goal of freeing Christian slaves. Some Catholic clergy, religious orders, and popes owned slaves, and the naval galleys of the Papal States were to use captured Muslim galley slaves in particular. Roman Catholic teaching began, however, to turn more strongly against certain forms of slavery from 1435.

When the Age of Discovery greatly increased the number of slaves owned by Christians, the response of the clergy, under strong political pressures, was ineffective in preventing the establishment of slave-owning societies in the colonies of Catholic countries. Earlier Papal bulls, such as Pope Nicholas V’s Dum Diversas (1452) and Romanus Pontifex (1454), permitting the "perpetual servitude" of Saracens and pagans in Africa, were used to justify the enslavement of natives and the appropriation of their lands during this era.

The depopulation of the Americas, and consequently the shortage of slaves, brought about by diseases brought over by the Europeans, as well as slaughter of the native populations, inspired increasing debate during the 16th century over the morality of slavery. One of the early shipments of Black Africans during the transatlantic slave trade was initiated at the request of Bishop Las Casas and authorized by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1517. However, Las Casas later rejected all forms of unjust slavery and became famous as the great protector of Indian rights.

A number of popes did issue papal bulls condemning "unjust" enslavement ("just" enslavement was still accepted as a form of punishment), and mistreatment of Native Americans by Spanish and Portuguese colonials; however, these were largely ignored. Nonetheless, Catholic missionaries such as the Jesuits worked to alleviate the suffering of Native American slaves in the New World. Debate about the morality of slavery continued throughout this period, with some books critical of slavery being placed on the Index of Forbidden Books by the Holy Office between 1573 and 1826. Capuchin missionaries were excommunicated for calling for the emancipation of black slaves in the Americas, although they were later reinstated when the Holy Office under Pope Innocent XI sided with them rather than the bishop which excommunicated them.

Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, the Church made great efforts to do missionary work among colored people in the Americas, whether slave or non-slave. On 22 December 1741, Pope Benedict XIV promulgated the papal bull "Immensa Pastorum Principis" against the enslavement of the indigenous peoples of the Americas and other countries. Pope Gregory XVI in his bull In supremo apostolatus (issued in 1839) also condemned slavery as contrary to human dignity. In 1866, the Holy Office of Pope Pius IX affirmed that, subject to conditions, it was not against divine law for a slave to be sold, bought, or exchanged. Pope Pope Leo XIII in 1888 wrote to the bishops of Brazil setting forth the position of the Church on slavery: he condemned the cruelties of the slave-trade and commended the abolition of slavery in the region.

In 1995, Pope John Paul II repeated the condemnation of "infamies", including slavery, issued by the Second Vatican Council:

Thirty years later, taking up the words of the Council and with the same forcefulness I repeat that condemnation in the name of the whole Church, certain that I am interpreting the genuine sentiment of every upright conscience.

Catholic teaching

An explanation of the Baltimore Catechism of Christian Doctrine used to teach the Catholic Faith in North America from 1885 to 1960 details the following explanation of the second sorrowful mystery of the rosary:

(2) The scourging of Our Lord at the pillar. This also has been explained. What terrible cruelty existed in the world before Christianity ! In our times the brute beasts have more protection from cruel treatment than the pagan slaves had then. The Church came to their assistance. It taught that all men are God’s children, that slaves as well as masters were redeemed by Jesus Christ, and that masters must be kind and just to their slaves. Many converts from paganism through love for Our Lord and this teaching of the Church, granted liberty to their slaves ; and thus as civilization spread with the teaching of Christianity, slavery ceased to exist. It was not in the power of the Church, however, to abolish slavery everywhere, but she did it as soon as she could. Even at present she is fighting hard to protect the poor negroes of Africa against it, or at least to moderate its cruelty.

The new Catechism of the Catholic Church published in 1994 sets out the official position:

The Seventh Commandment forbids acts or enterprises that .... lead to the enslavement of human beings, to their being bought, sold and exchanged like merchandise, in disregard for their personal dignity. It is a sin against the dignity of persons and their fundamental rights to reduce them by violence to their productive value or to a source of profit. St. Paul directed a Christian master to treat his Christian slave "no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother .... both in the flesh and in the Lord."

Development

Since the Middle Ages, the Christian understanding of slavery has seen significant internal conflict and endured dramatic change. Today, the concept of slavery as private property is condemned by the Church, which classifies it as the stealing of a person’s human rights, a concept of classical liberalism that has dominated most of the Western world for the past century. However, the Church has never viewed slavery as intrinsically evil, and even today some forms of servitude, such as penal slavery, continue to be made use of.

Definitions

Like secular legal systems, the Church has at different times distinguished between various forms and elements of "slavery". At particular moments there have been different attitudes to the making of slaves, or "new enslavement", the trafficking and trading of slaves, and the basic ownership of slaves. A distinction was long made between "just" and "unjust" slavery, and whether a particular slave was "justly" or "unjustly" kept in that condition could depend on his religious status. The church long accepted the right of a person to sell himself or his children into slavery, which was sometimes fairly common, or to be sentenced to slavery as a criminal punishment. In addition, slavery was long regarded as essentially an issue of secular law.

They contrast this with "just servitude" in which a metaphysical distinction is made between owning a person as an object, and only owning the work of that person. In practical terms a person could be bought sold or exchanged as a form of "just servitude" subject to certain conditions. Slavery for debt was typically legally a different matter under both pre-Christian and Christian legal systems; it might be only for a period, and the owner typically did not have the right to sell the slave without his agreement, and had other restrictions. It often was more a form of indentured labour. Ancient legal systems, included those of the Israelites seen in the Hebrew Bible, also typically distinguished between "native" and foreign slaves, with much better protection for the former. This distinction was transferred to Christian versus non-Christian slaves, sometimes with a component of "origin" as well, for example in Anglo-Saxon laws, but remained very important in Christian thinking and legal systems, in particular for the making of new slaves. The Christian church very early treated slaves as persons, and they were allowed to be baptised, marry, and also be ordained. This tended to be reflected in slavery laws of Catholic countries, so that French slaves, for example, were allowed to marry slaves or free people, though neither baptism nor marrying a free person emancipated them - an issue in the leading French legal case of Jean Boucaux (1737).

A Catholic layman (Cochin) reviewing the moral arguments that underpinned the common Church teaching and definitions relating to “just” slavery wrote in 1861:

- “They teach concerning slavery what was taught yesterday and the day before, but what no priest or layman believes any longer today. They teach that slavery is not unlawful, firstly, when it proceeds from a legitimate war or voluntary sale; secondly, provided it respects the soul, body, family, and instruction of the slave. But I challenge anyone to show me today, throughout all Christianity, a single slave who has become such as a prisoner of war or through voluntary sale, to say nothing of the manner in which he is treated.”

In 1530 the first judges in Audiencia of "New Spain" contrasted the "servitude" as practised in Christian Europe with that of the Indians in a letter to Charles V: "they [Indians] treat slaves as relations, while the Christians treat them as dogs."

Slavery in the New Testament

In several Pauline epistles, and the First Epistle of Peter, slaves (however the Greek word used, δοῦλοι , is ambiguous, also being used in context to mean servant), are admonished to obey their masters, as to the Lord, and not to men; however Masters were told to serve their slaves "in the same way" and "even better" as "brothers", to not threaten them as God is their Master as well. Slaves who are treated wrongly and unjustly are likened to the wrongs that Christ unjustly suffered, and Masters are told that God "shows no favoritism" and that "anyone who does wrong will be repaid for his wrong."

The Epistle to Philemon has become an important text in regard to slavery; it was used by pro-slavery advocates as well as by abolitionists. In the epistle, Paul writes that he is returning Onesimus, a fugitive slave, back to his master Philemon; however, Paul also entreats Philemon to regard Onesimus as a beloved brother in Christ, rather than as a slave. Cardinal Dulles points out that, "while discreetly suggesting that he manumit Onesimus, [Paul] does not say that Philemon is morally obliged to free Onesimus and any other slaves he may have had." However, in his Homilies on Philemon, Chrysostom actually opposes unfair and unjust forms of slavery by stating that those who own slaves are to passionately love their slaves with the very Love of Christ for humanity: "this ... is the glory of a Master, to have grateful slaves. And this is the glory of a Master, that He should thus love His slaves ... Let us therefore be stricken with awe at this so great love of Christ. Let us be inflamed with this love-potion. Though a man be low and mean, yet if we hear that he loves us, we are above all things warmed with love towards him, and honor him exceedingly. And do we then love? And when our Master loves us so much, we are not excited?"

In the First Epistle to Timothy, slave traders are condemned, and listed among the sinful and lawbreakers. The First Epistle to the Corinthians describes lawfully obtained manumission as the ideal for slaves.

Early Christianity

Early Christianity encouraged kindness towards slaves. The rape of slaves, considered entirely normal in most preceding systems, was naturally prohibited under the general very strict ban on sex outside marriage in any circumstances, though the effectiveness of the ban of this naturally varied. Christianity recognised marriage of sorts among slaves, freeing slaves was regarded as an act of charity. In Roman law slaves were regarded as property not persons, but this was not the Christian position. Slaves could marry and be ordained as priests. It has been argued that this difference in legal status in the long term undermined the whole position of slavery.

Nevertheless, early Christianity rarely criticised the actual institution of slavery. Though the Pentateuch gave protection to fugitive slaves, the Roman church often condemned with anathema slaves who fled from their masters, and refused them Eucharistic communion.

In 340 the Synod of Gangra in Asia Minor, condemned certain Manicheans for a list of twenty practices including forbidding marriage, not eating meat, urging that slaves should liberate themselves, abandoning their families, ascetism and reviling married priests. The later Council of Chalcedon, declared that the canons of the Synod of Gangra were ecumenical (in other words, they were viewed as conclusively representative of the wider church).

Augustine of Hippo, who renounced his former Manicheanism, opposed unfair and unjust forms of slavery by observing that they originate with human sinfulness, rather than the Creator’s original just design of the world which had initially included the basic equality of all human beings as good creatures made in God’s image and likeness.

John Chrysostom described slavery as 'the fruit of covetousness, of degradation, of savagery ... the fruit of sin, [and] of [human] rebellion against ... our true Father' in his Homilies on Ephesians. Moreover, quoting partly from Paul the Apostle, Chrysostom opposed unfair and unjust forms of slavery by giving these instructions to those who owned slaves: " 'And ye masters', he continues, 'do the same things unto them'. The same things. What are these? 'With good-will do service' ... and 'with fear and trembling' ... toward God, fearing lest He one day accuse you for your negligence toward your slaves ... 'And forbear threatening;' be not irritating, he means, nor oppressive ... [and masters are to obey] the law of the common Lord and Master of all ... doing good to all alike ... dispensing the same rights to all". Chrysostom preaching on Acts 4:32–4:33 in a sermon entitled, "Should we not make it a heaven on earth?", stated, "I will not speak of slaves, since at that time there was no such thing, but doubtless such as were slaves they set at liberty...

However, Saint Patrick (415-493), himself a former slave, argued for the abolition of slavery, as had Gregory of Nyssa (c.335-394), and Acacius of Amida (400-425). Origen (c.185-254) favoured the Jewish practice of freeing slaves after seven years. Saint Eligius (588-650) used his vast wealth to purchase British and Saxon slaves in groups of 50 and 100 in order to set them free.

Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I in his Pastoral Care (c. 600), which remained a popular text for centuries, wrote "Slaves should be told ...[not] to despise their masters and recognise they are only slaves". In his Commentary on the Book of Job he wrote that "All men are equal by nature but .... a hidden dispensation by providence has arranged a hierarchy of merit and rulership, in that differences between classes of men have arisen as a result of sin and are ordained by divine justice". He directed slaves to be employed by the monasteries as well as forbidding the unrestricted allowance of slaves joining the monastery to escape their servitude. Upon manumitting two slaves held by the Church, he wrote:

Since our Redeemer, the Maker of every creature, was pleased mercifully to assume human flesh in order to break the chain of slavery in which we were held captive, and restore us to our pristine liberty, it is right that men, whom nature from the beginning produced free, and whom the law of nations has subjected to the yoke of slavery, should be restored by the benefit of manumission to the liberty in which they were born.

— Pope Gregory the Great

However, papal estates continued to possess several hundred slaves despite Gregory’s rhetoric on the natural liberty of mankind.

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Saint Thomas Aquinas taught that, although the subjection of one person to another (servitus) could not be derived from the natural law, it could be appropriate based on an individual’s actions and socially useful in a world impaired by original sin.

Aquinas did not believe slavery was justified by natural law, since he thought that all men are equal by nature. For Aquinas, slavery only arises through positive law.

"St Thomas Aquinas in mid-thirteenth century accepted the new Aristotelian view of slavery as well as the titles of slave ownership derived from Roman civil law and attempted - without complete success - to reconcile them with Christian patristic tradition. He takes the patristic theme... that slavery exists as a consequence of original sin and says that it exists according to the "second intention" of nature; it would not have existed in the state of original innocence according to the "first intention" of nature; in this way he can explain the Aristotelian teaching that some people are slaves "by nature" like inanimate instruments, because of their personal sins; for since the slave cannot work for his own benefit slavery is necessarily a punishment. He accepts the symbiotic master-slave relationship as being mutually beneficial. There should be no punishment without some crime, so slavery as a penalty is a matter of positive law. St Thomas' explanation continued to be expounded at least until the end of the 18th century."

Jarrett & Herbert concur with historian Paul Weithman, explaining that Aquinas held that slavery could not be arrived at as a process of Natural Law. It could, thus, only be arrived at as a consequence of man’s action. Thus, slavery could not be the natural state of man, but could be imposed as a legal or political consequence for actions. Aquinas' contemporary, the Franciscan Saint Bonaventura argued on ethical grounds that slavery was "infamous" and "perverting virtue", but accepted its legality.

Early Christianity

At least two early popes and several other major figures were former slaves, for example Popes Callixtus I, Pius I The Catholic Encyclopedia argues that, in order for the Church to have condemned slavery, it would have had to be willing to incite a revolution that could have resulted in the destruction of "all civilization".

"Primitive Christianity did not attack slavery directly; but it acted as though slavery did not exist..... To reproach the Church of the first ages with not having condemned slavery in principle, and with having tolerated it in fact, is to blame it for not having let loose a frightful revolution, in which, perhaps, all civilization would have perished with Roman society."

Mark Brumley makes the following points regarding early Christianity and slavery:

- First, while Paul told slaves to obey their masters, he made no general defense of slavery, anymore than he made a general defense of the pagan government of Rome, which Christians were also instructed to obey despite its injustices (cf. Rom. 13:1-7). He seems simply to have regarded slavery as an intractable part of the social order, an order that he may well have thought would pass away shortly (1 Cor. 7:29-31).

- Second, Paul told masters to treat their slaves justly and kindly (Eph 6:9; Col 4:1), implying that slaves are not mere property for masters to do with as they please.

- Third, Paul implied that the brotherhood shared by Christians is ultimately incompatible with chattel slavery. In the case of the runaway slave Onesimus, Paul wrote to Philemon, the slave’s master, instructing him to receive Onesimus back “no longer as a slave but more than a slave, a brother” (Philem. 6). With respect to salvation in Christ, Paul insisted that “there is neither slave nor free ... you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:27-28).

- Fourth, the Christian principles of charity (“love your neighbor as yourself") and the Golden Rule (“Do unto others as you would have them to do unto you”) espoused by the New Testament writers are ultimately incompatible with chattel slavery, even if, because of its deeply established role as a social institution, this point was not clearly understood by all at the time.

- Fifth, while the Christian Empire didn’t immediately outlaw slavery, some Church fathers (such as Gregory of Nyssa and John Chrysostom) strongly denounced it. But then, the state has often failed to enact a just social order in accordance with Church teachings.

- Sixth, some early Christians liberated their slaves, while some churches redeemed slaves using the congregation’s common means. Other Christians even sacrificially sold themselves into slavery to emancipate others.

- Seventh, even where slavery was not altogether repudiated, slaves and free men had equal access to the sacraments, and many clerics were from slave backgrounds, including two popes (Pius I and Callistus). This implies a fundamental equality incompatible with slavery.

- Eighth, the Church ameliorated the harsher aspects of slavery in the Empire, even trying to protect slaves by law, until slavery all but disappeared in the West. It was, of course, to re-emerge during the Renaissance, as Europeans encountered Muslim slave traders and the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In 340 the Synod of Gangra in Asia Minor, condemned certain Manicheans for a list of twenty practices including forbidding marriage, abandoning their families, slaves despising masters and running away under the pretext of piety, false ascetism and reviling married priests

Medieval period

The main thrust of the church’s policy on Slavery in early medieval Europe was to end the enslavement of previously free Christians. Slaves who converted or were baptised as infants in slavery were not covered. It was common practice, both in the ancient world and the Migration period societies which were Christianized, for captives in war, often including the whole population of captured cities, to be enslaved as war booty. This remained acceptable to the Church in the case of non-Christian captives, but not for Christian ones. Getting this principle accepted in Christian societies was difficult and could take a matter of centuries, as it created a great loss of profit for the military elites. According to the Cambridge Economic History of Europe "one of the finest achievements of Christian ethics was the enforcement of respect for this maxim [that free Christians could not be enslaved], slowly to be sure, for it is still being recalled in England early in the eleventh century, but in the long run most effectively."

Slave trafficking was also often condemned, and was clearly regarded by Christian populations as an ethically very dubious trade, rife with abuse (this had been the case before Christianity as well). This was especially so when it involved the sale of Christians to non-Christians, which was often forbidden (for these purposes the Eastern Orthodox might not always be regarded as Christian). The export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands was often prohibited, for example at the Council of Koblenz in 922, and the Council of London (1102). The ownership of slaves was not condemned in the same way, except that Jews, typically the only non-Christian group accepted in medieval Christian societies, were forbidden to own Christian slaves.

By the end of the Medieval period, enslavement of Christians had been largely abolished throughout Europe although enslavement of non-Christians remained permissible. Serfdom had almost entirely replaced agricultural slavery, and by then was itself largely dying out in Western Europe. Labour shortages after the mid-14th century Black Death were among the factors that broke the serf system. Chattel slavery continued on the fringes of Christendom, and had a revival in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance with Muslim captives. As in other societies, new slaves were continually needed, and the wars of the Reconquista seem to have ensured that Spain and Portugal had the slowest declines in slavery, so that they still had significant numbers of slaves when the Age of Discovery began. England had also been relatively late to lose slavery, which declined sharply after the Norman Conquest did away with the traditional Anglo-Saxon legal framework, and brought in Norman government more heavily influenced by the Church. Over 10% of England’s population entered in the Domesday Book in 1086 were slaves, a far higher figure than in France at the same date. Paradoxically, church bodies remained slave-owners as church leaders fought new enslavement and the slave-trade. As an administrative organization, the Church was conservative and had rules forbidding the alienation of church property. This, and the survival of church records, accounts for the last records of agricultural slaves in England being from monastic properties in the 1120s, much later than in France, where they disappear from the records of large monasteries by the mid-9th century.

What is usually termed "the ransoming of captives" was one of the traditional Seven Acts of Mercy; this meant slaves as well as prisoners of war, who could still be held for ransom even after their enslavement and sale was unacceptable. Irish Council of Armagh (1171) decreed the liberation of all English slaves, but this was after, and specifically linked to, the Norman invasion of Ireland.

Christian people could be enslaved as a criminal punishment, or for debt, or sell themselves or their children. In 655 the Ninth Council of Toledo, in order to keep priests celibate, ruled that all children of clerics were to be enslaved. In 1089, Pope Urban II ruled at the Synod of Melfi that the wives of priests were to be enslaved.

.... disabilities of all kinds were enacted and as far as possible enforced against the wives and children of ecclesiastics. Their offspring were declared to be of servile condition .... The earliest decree in which the children were declared to be slaves, the property of the Church, and never to be enfranchised, seems to have been a canon of the Synod of Pavia in 1018. Similar penalties were promulgated later on against the wives and concubines (see the Synod of Melfi, 1189, can. xii), who by the very fact of their unlawful connection with a subdeacon or clerk of higher rank became liable to be seized as slaves ...

Laws sometimes stated that conversion to Christianity, especially by Muslims, should result in the emancipation of the slave, but as such conversions often resulted in the freed slave returning to his home territory and reverting to his old religion, for example in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, which had such laws, provisions along these lines were often ignored and became less used.

Helping and freeing slaves

There has been a consistent tradition of charitable aid to slaves, without necessarily challenging the institution of slavery itself. Saint Paul was the first of many authorities to say that slaves should be treated kindly, and the granting of freedom by slave-owners (already common in Roman life) was encouraged, especially on the conversion of the owner, or their death. The Anglo-Saxon Synod of Chelsea (816) said that the death of a bishop should be marked by the enfranchisement of all his(?) English (not foreign) slaves enslaved during his life; later pronouncements called for enfranchisement on such occasions, and there was evidently a widespread tradition of such actions.

Christian captives enslaved were a particular concern, and their trafficking to non-Christian owners regarded as especially disgraceful; this was repeatedly forbidden by the church and many figures from the Early Medieval to Early Modern periods took part in the buying back of Christian slaves from their non-Christian owners. One of the traditional Seven Acts of Mercy is now usually given as the "ransoming of captives", but this originally meant slaves or prisoners of war, a distinction that mostly emerged during the Middle Ages, as the sale by Christians of their prisoners became unacceptable, though holding those likely to produce a ransom as prisoners for long periods was not.

The liberation of their own slaves or the buying of slaves to liberate them is a constant theme in early medieval hagiographies. The Frankish Saint Eligius, a goldsmith turned bishop, used his wealth to do so on a large scale, apparently not restricting his actions to Christian slaves. Others used church funds for this, which was permitted by various church councils. The intriguing Queen Bathild (died 680), wife of the Frankish king Clovis II and then regent for her son, was apparently an Anglo-Saxon relative of Ricberht of East Anglia, the last pagan king there, who was either captured by pirates or sold into slavery, probably when he was succeeded by Sigeberht, who was soon to convert to Christianity. She was apparently given to Clovis as a present, but emerged as his queen, and acted against the slave trade, forbidding the export of slaves and using her own money to buy back slaves, especially children.

Societies and clerical orders were founded for the purpose of freeing Christian slaves. The best known of these are the Trinitarian Order and the Mercedarians. The Trinitarians were founded in France in 1198 by Saint John of Matha, with the original aim of ransoming captives in the Crusades. The Mercedarians are an order of friars founded in Barcelona in 1218 by Saint Peter Nolasco, whose particular original mission was the saving of Christian slave-captives in the wars between Christian Aragon and Muslim Spain (Al-andalus). Both operated by collecting money to redeem the captives, and organizing the business of buying them back, so that they were useful to families who already had the money.

The French priest Saint Vincent de Paul (1581–1660) had been captured by Barbary corsairs and enslaved for some years before escaping. He used his position as chaplain to the aristocrat in charge of the French galley fleet to run missions among the slaves and ameliorate their conditions, without seriously challenging the galley-slave system itself.

Wars against Muslims

The position of the Western Church that Christian captives could not be enslaved mirrored that in Islam, which had the same condition in respect of Muslim captives. This meant that in wars involving the two religions, all captives were still liable to be enslaved when captured by the other religion, as regularly happened in the Crusades and the Spanish Reconquista. Coastal parts of Europe remained prey throughout the period to razzias or slaving raids by Barbary corsairs which led to many coastal areas being left unpopulated; there were still isolated raids on England and Ireland as late as the 17th century. "As a consequence of the wars against the Mussulmans and the commerce maintained with the East, the European countries bordering on the Mediterranean, particularly Spain and Italy, once more had slaves: Turkish prisoners and also, unfortunately, captives imported by conscienceless traders .... this revival of slavery, lasting until the seventeenth century, is a blot on Christian civilization". Many Medieval popes condemned the enslavement by Muslims of Christians. Several religious orders were organized to redeem such enslaved Christians. There was, however, never any general condemnation of slavery or tied servitude.

Slavery incorporated into canon law

In the early thirteenth century, official support for some kinds of servitude was incorporated into Canon Law (Corpus Iuris Canonici), by Pope Gregory IX.

Slavery was imposed as an ecclesiastical penalty by General Councils and local Church councils and Popes, 1179–1535...

(a) The crime of assisting the Saracens 1179–1450.....

(b) The crime of selling Christian slaves to the Saracens 1425. Pope Martin V issued two constitutions. Traffic in Christian slaves was not forbidden, but only their sale to non Christian masters.

(c) The crime of brigandage in the Pyrenees mountainous districts, 1179.

(d) Unjust aggression or other crimes, 1309–1535. The penalty of capture and enslavement for Christian families or cities or states was enacted several times by Popes. Those sentenced included Venetians in 1309.

During the War of the Eight Saints, Pope Gregory XI excommunicated all members of the government of Florence and placed the city under interdict, and legalizing the arrest and enslavement of Florentines and the confiscation of their property throughout Europe.

Revival of slavery in the Early Modern Period

By the end of the Middle Ages slavery had become rare in Northern Europe, but less so around the Mediterranean, where there was more contact with non-Christian societies. Some Italian maritime states remained involved in the slave-trade, but the only Christian area where agricultural slaves were economically important was the south of the Iberian peninsula, where slaves from wars with Muslims, both in the Reconquista and Christian attempts to expand into North Africa, had recently begun to be augmented with slaves taken from sub-Saharan Africa. Unfortunately, Spain and Portugal were the leaders in the Age of Discovery, and took their slave-making attitudes to their new territories in the Americas.

The first African slaves arrived in the Spanish territory of Hispaniola in 1501. Over the next centuries, millions of Africans were taken to the New World in the African Slave Trade.

The theoretical approach of the church to contacts with less-developed peoples in Africa and the Americas carried over from conflicts with Muslims the principle that resistance to Christian conquest, and to conversion, was sufficient to make people, including whole populations, "enemies of Christ", who could be justly enslaved, and then held in slavery even after conversion.

Before Columbus

Europe had been aware since antiquity of the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic 100 kilometres off Africa, and occupied by the Guanches, a people related to the North African Berber peoples, who lived at a simple level without towns, long-range ships or writing, and had intermittent contacts with seafarers from elsewhere. In 1402 the Spanish began the process of conquest, island by island, in what was to be in many ways a rehearsal for their New World conquests. The process lasted until the final defeat of resistance in Tenerife in 1496, and was accompanied by the removal of large parts of the Guanche population as slaves, to the extent that distinct Guanche communities, language and culture have long ceased to exist, although genetic studies find a considerable proportion of what are considered Guanche genes among modern Canarians. There were a number of Church injunctions against the enslavement of the Guanches, which seem to have had little effect. In 1435 Pope Eugene IV condemned slavery, of other Christians, in Sicut Dudum; furthermore, he explicitly forbade the enslavement of the Guanches.

Pope Pius II and Pope Sixtus IV also condemned the enslavement of Christians. On the contrary scholars who are specialist in the field point out that slavery continued since the prohibition of Pius II related only to the recently baptised. This being confirmed by Pope Urban VIII (7 October 1462, Apud Raynaldum in Annalibus Ecclesiasticis ad ann n.42) who referred to those covered by the prohibitions of Pius II as "neophytes".

1454 Pope Nicholas granted King Alfonso V "...the rights of conquest and permissions previously granted not only to the territories already acquired but also those that might be acquired in the future".

We [therefore] weighing all and singular the premises with due meditation, and noting that since we had formerly by other letters of ours granted among other things free and ample faculty to the aforesaid King Alfonso – to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profit...

In 1456, Pope Calixtus III confirmed these grants to the Kings of Portugal and they were renewed by Pope Sixtus IV in 1481; and finally in 1514 Pope Leo repeated verbatim all these documents and approved, renewed and confirmed them.

These papal bulls came to serve as a justification for the subsequent era of slave trade and European colonialism.

Despite the several papal condemnations of slavery in the 15th and 16th centuries, Spain and Portugal were never explicitly forbade from partaking in slavery.

In 1488, Pope Innocent VIII accepted the gift of 100 slaves from Ferdinand II of Aragon, and distributed those slaves to his cardinals and the Roman nobility.

Spanish New World

Slavery was part of the indigenous cultures much before the landfall of the Europeans in America. After the Europeans made landfall in America in 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella saw that, if Spain did not receive from the Pope in regard to the American "Indies" the same authority and permissions which Portugal had received in regard of West Africa, then Spain would be at a disadvantage in making use of her newly discovered territories. Accordingly, Pope Alexander VI was approached and already on 3 May 1493 he issued two bulls on the same day in both of which he extended the identical favours, permissions, etc. granted to the Monarchy of Portugal in respect of West Africa to the Monarchy of Spain in respect of America.....and to reduce their persons into perpetual slavery...wherever they may be.

Although the church was excited by the potential for huge numbers of conversions in the New World, the clergy sent there were often horrified by the methods used by the conquerors, and tensions between church and state in the new lands grew rapidly. The encomienda system of forced or tenured labour, begun in 1503, often amounted to slavery, though it was not full chattel slavery. The Leyes de Burgos (or Laws of Burgos), were issued by Ferdinand II (Catholic) on 27 December 1512, and were the first set of rules created to control relations between the Spaniards and the recently conquered indigenous people, but though intended to improve the treatment of the Indians, they simply legalized and regulated the system of forced Indian labour. During the reign of Charles V, the reformers gained steam, with the Spanish missionary Bartolomé de las Casas as a notable leading advocate. His goal was the abolition of the encomienda system, which forced the Indians to abandon their previous lifestyle and destroyed their culture. His active role in the reform movement earned Las Casas the nickname, "Defender of the Indians". He was able to influence the king, and the fruit of the reformers' labour was the New Laws of 1542. However these provoked a revolt by the conquistadors, led by Gonzalo Pizarro, the half-brother of Francisco Pizarro, and the alarmed government revised them to be much weaker to appease them. Continuing armed indigenous resistance, for example in the Mixtón War (1540–41) and the Chichimeca War of 1550 resulted in the full enslavement of thousands of captives, often out of the control of the Spanish government.

The second Archbishop of Mexico (1551–72), the Dominican Alonso de Montúfar, wrote to the king in 1560 protesting the importation of Africans, and questioning the "justness" of enslaving them. Tomás de Mercado was a theologian and economist of the School of Salamanca who had lived in Mexico and whose 1571 Summa de Tratos y Contratos ("Manual of Deals and Contracts") was scathing about the morality of the enslavement of Africans in practice, though he accepted "just-title" slaves in theory.

The Church’s view on the African Slave Trade in Latin America mimicked that of which they treated it in Europe, as in they did not view them as morally equal. The Church, however, did mandate slaves to be baptized, perform the sacraments, and attend Sunday mass. Slaveholders were also required to give slaves the Lord’s day of rest. Uniquely, in Latin America the Church made marriage a requirement and the couple could not be forcefully separated.

However, the Church was subservient to slaveholders. Priests, nuns, and brotherhoods all had large numbers of slaves under them. For example, the largest convent in Mexico City, Mexico bordered the slave market. The nuns purchased personal slaves and slaves to tend to their convent facilities. A particularly revealing case of the Church’s participation in the slave trade are the records of lottery prizes from the Santa Casa da Misericordia in Brazil. Child slaves were auctioned off for the large Catholic Charity. Joaquim Nabuco, a Brazilian abolitionist, is quoted saying, " No priest ever tried to stop a slave auction; none ever denounced the religious regimen of the slave quarters. The Catholic Church, despite its immense power in a country still greatly fanaticized by it, never raised its voice in Brazil in favor of emancipation."

Requerimiento

The Spanish Requerimiento, in relation to the Spanish invasion of South America, was a legalistic proclamation supposed to be read to local populations in the New World, demanding that the local populations convert to Roman Catholicism, on pain of slavery or death, and intended to give legal colour to the actions of the Spanish. This drew on earlier precedents going back centuries, used in conflicts with the Muslims and Guanches, and originally perhaps copying the Islamic dawah. The most famous version was used between 1510 and 1556, but others were used until the 18th century. It was introduced after Dominican friars accompanying the conquistadors protested to the Crown at the enslavement of the Indians. Comparing the situation to Spain’s wars against the Moors, the clerics claimed that Muslims had knowledge of Christ and rejected him, so that waging a crusade against them was legitimate. In contrast, wars against the Native Americans, who had never come into contact with Christianity were unacceptable. As a response to this position, the Requerimiento provided a religious justification for the conquest of the local populations, on the pretext of their refusing the "legitimate" authority of the Kings of Spain and Portugal, as granted by the Pope.

16th century

Slavery in Europe

Slavery in Europe, mainly around the Mediterranean, continued, and was increased by the increased size of Mediterranean navies to combat the powerful Ottoman navy. The main type of naval ship in the Mediterranean, unlike the Atlantic and Northern seas, was the galley, rowed by galley-slaves; use of the galley only declines from about 1600. The navy of the Papal States was no different from that of Venice, France, Genoa and other naval powers. Galley-slaves were recruited by criminal sentencing, usually for a term of years many never survived, as well as capture in war, mostly of Muslims, and sometimes the African slave-trade. Some of the Popes were personally involved in the purchase and use of galley-slaves. The Ottoman admiral Turgut Reis was captured and made a Genoan galley-slave for nearly four years before being imprisoned and eventually ransomed in 1544. After the battle of Lepanto approximately 12,000 Christian galley slaves were freed from the Turks.

In 1535 Pope Paul III removed the ability of slaves in Rome to claim freedom by reaching the Capitol Hill, although this was restored some years later. He "declared the lawfulness of slave trading and slave holding, including the holding of Christian slaves in Rome".

In 1639 Pope Urban VIII forbade the slavery of the Indians of Brazil, Paraguay, and the West Indies, yet he purchased non-Indian slaves for himself from the Knights of Malta, probably for the Papal galleys. The Knights of Malta attacked pirates and Muslim shipping, and their base became a centre for slave trading, selling captured North Africans and Turks. Malta remained a slave market until well into the late 18th century. It required a thousand slaves to equip merely the galleys of the Order.

Sublimis Deus

In the bull Sublimus Dei (1537), Pope Paul III prohibited the enslavement of indigenous peoples of the Americas, asserting that they "should not be deprived of their liberty":

...The exalted God loved the human race so much that He created man in such a condition that he was not only a sharer in good as are other creatures, but also that he would be able to reach and see face to face the inaccessible and invisible Supreme Good... Seeing this and envying it, the enemy of the human race, who always opposes all good men so that the race may perish, has thought up a way, unheard of before now, by which he might impede the saving word of God from being preached to the nations. He (Satan) has stirred up some of his allies who, desiring to satisfy their own avarice, are presuming to assert far and wide that the Indians...be reduced to our service like brute animals, under the pretext that they are lacking the Catholic faith. And they reduce them to slavery, treating them with afflictions they would scarcely use with brute animals... by our Apostolic Authority decree and declare by these present letters that the same Indians and all other peoples - even though they are outside the faith - ...should not be deprived of their liberty... Rather they are to be able to use and enjoy this liberty and this ownership of property freely and licitly, and are not to be reduced to slavery...

The bull was accompanied by the Pastorale Officium, which attached a latae sententiae excommunication rescindable only by the pope for those who attempted to enslave the Indians or steal their goods. Stogre (1992) notes that "Sublimus Dei" is not present in Denzinger, a compendium of the Church’s teachings, and that the executing brief for it ("Pastorale officium") was annulled the following year. Davis (1988) asserts it was annulled due to a dispute with the Spanish crown. The Council of The West Indies and the Crown concluded that the documents broke their patronato rights and the Pope withdrew them, though they continued to circulate and be quoted by Las Casas and others who supported Indian rights.

Falola (2007) asserts that the bull related to the native populations of the New World and did not condemn the transatlantic slave trade stimulated by the Spanish monarchy and the Holy Roman Emperor. However the bull did condemn the enslavement of all other people, seeming to indirectly condemn the transatlantic slave trade also. The bull was a significant defense of Indian rights.

In a decree dated 18 April 1591 (Bulla Cum Sicuti), Gregory XIV ordered reparations to be made by Catholics in the Philippines to the natives, who had been forced into slavery by Europeans, and he commanded under pain of excommunication of the owners that all native slaves in the islands be set free.

In 1545, Paul repealed an ancient law that allowed slaves to claim their freedom under the Emperor’s statue on Capitol Hill, in view of the number of homeless people and tramps in the city of Rome. The decree included those who had become Christians after their enslavement and those born to Christian slaves. The right of inhabitants of Rome to publicly buy and sell slaves of both sexes was affirmed.

- “[we decree] that each and every person of either sex, whether Roman or non-Roman, whether secular or clerical, and no matter of what dignity, status, degree, order or condition they be, may freely and lawfully buy and sell publicly any slaves whatsoever of either sex, and make contracts about them as is accustomed to be done in other places, and publicly hold them as slaves and make use of their work, and compel them to do the work assigned to them....irrespective of whether they were made Christians after enslavement, or whether they were born in slavery even from Christian slave parents according to the provisions of common law."

Stogre (1992) asserts that the lifting of restrictions was due to a shortage of slaves in Rome. In 1547 Pope Paul III also sanctioned the enslavement of the Christian King of England, Henry VIII, in the aftermath of the execution of Sir Thomas More In 1548 he authorized the purchase and possession of Muslim slaves in the Papal states.

17th century

The Jesuit reductions, highly organized rural settlements where Jesuit missionaries presided over Indian communities, were begun in 1609, and lasted until the suppression of the order in Spain in 1767. The Jesuits armed the Indians, who fought pitched battles with Portuguese Bandeirantes or slave-hunters. The Holy Office of the Inquisition was asked about the morality of enslaving innocent blacks (Response of the Congregation of the Holy Office, 230, 20 March 1686). The practice was rejected, as was trading such slaves. Slaveholders, the Holy Office declared, were obliged to emancipate and even compensate blacks unjustly enslaved.

18th century

In Compendium Institutionum Civilium, cardinal Gerdil asserts that slavery is compatible with natural law and does not break equality between humans, as slaves retain some rights such as the right to be treated humanely by their masters.

Pope Benedict XIV condemned the enslavement of Native Americans, specifically in the Portuguese colonies, in the papal bull Immensa Pastorum in 1741.

The movement towards abolition of slavery

The 18th century saw the massive expansion of the transatlantic slave trade in conjunction with European colonialism. Around the end of the century, various abolitionist movements formed in Europe and the Americas with the stated aim of abolishing slavery and the slave trade. These movements were related to the Enlightenment but generally based on Christian ethical principles; in the English-speaking countries many leading figures were Non-conformist Protestants.

French Catholic intellectuals who were notable writers against slavery included Montesquieu and later the radical priests Guillaume-Thomas Raynal and the Abbé Gregoire.

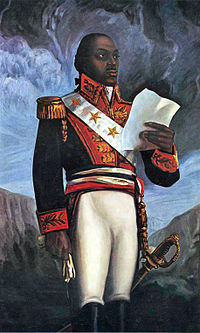

Legal cases such as the French case of Jean Boucaux v. Verdelin of 1738 and the English Somersett's Case (1772) essentially ended the status of slave in the home countries, but without affecting the colonies. The French Revolution, in which Raynal and Gregoire were notable figures, did not initially have emancipation as a goal, but after failing to stamp out the Haitian Revolution, led by the devout Catholic ex-slave Toussaint L'Overture, and alarmed by British attempts to link up with the slave rebels, in 1794 the French entirely abolished slavery in all French territories; however this was reversed by Napoleon when he gained power.

The British followed in 1807 with the Slave Trade Act 1807, which outlawed all international slave-trafficking, but not slave owning, which was legal in the British Empire until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. From 1807 the British began to use their naval power and diplomatic pressure to lead the international movement eradicating international slave-trafficking completely, which was eventually almost entirely successful.

In 1810, a Mexican Catholic Priest, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who is also the Father of the Mexican nation, declared slavery abolished, but this was not official until the War of Independence finished.

Pius VII joined the declaration of the Congress of Vienna, in 1815, urging the suppression of the slave trade. By now the major consistent opposition to this came from Spain and Portugal, to whose empires a continued supply of new slaves remained economically very important. In the United States the slave population was largely able to maintain its numbers, and even many slave-owners accepted the evils of the African slave-trade and the need to abolish it.

Pius wrote letters to the restored King of France in 1814 and the King of Portugal in 1823 urging the same thing. By now the Papacy was under political pressure from the British government, as British support was needed at the Congress of Vienna for the restoration of the Papal States.

On reviewing the history of the Church with respect slavery Maxwell (1975) concludes that "In Catholic countries the abolition of slavery has been due mainly to humanist influences". The political philosopher Luigi Sturzo argued that the change in attitude to slavery among many Christian thinkers followed its legal abolition rather than preceding it.

In supremo apostolatus

In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI issued a bull, with the incipit In supremo apostolatus in which he condemned slavery, with particular reference to New World colonial slavery and the slave trade, calling it "inhumanum illud commercium." The exact meaning and scope of the Bull was disputed at the time, and remains so among historians. That new enslavements and slave-trading are condemned and forbidden absolutely is clear, but the language in the passage quoted below and other passages was not sufficiently specific to make clear what, if anything, the bull had to say about the ongoing ownership of those already slaves, although their sale seemed to be prohibited. There was certainly no clear call for the emancipation of all existing slaves, as had already happened in the British and French Empires. Britain ended slavery in England, but it continued in British African colonies until the 1940s.

"We, by apostolic authority, warn and strongly exhort... that no one in the future dare to bother unjustly, despoil of their possessions, or reduce to slavery Indians, Blacks or other such peoples... We prohibit and strictly forbid any Ecclesiastic or lay person from presuming to defend as permissible this trade in Blacks under no matter what pretext or excuse, or from publishing or teaching in any manner whatsoever, in public or privately, opinions contrary to what We have set forth in these Apostolic Letters" (In supremo apostolatus, 1839).

The Bull was ignored by the Spanish and Portuguese governments, both at that point of an anti-clerical cast and on poor terms with the Vatican generally. The ambiguity in the text allowed some Catholics, including some bishops in the United States and elsewhere, to continue to say that the owning of slaves was permitted by the church, while others claimed that it was a general condemnation of slave-owning. In terms of theology, the position of the church remained unchanged, that slavery was not intrinsically evil. John Henry Newman, in a letter to fellow convert Thomas William Allies, disagreed with him that slavery was intrinsically evil and instead compared slavery to despotism. Stating that neither is intrinsically evil, so though he believed St. Paul would have ended both if he could he was not bound to try as he could not. That slavery was also not per se a sin and some good could come from it. It was not until the last Catholic country to retain legal slavery, Brazil, had abolished it in 1888, that the Vatican pronounced more clearly against slavery as such (that is, the owning of slaves; see below)

Pope Leo XIII

By 1890, slavery was no longer a significant issue for most governments of Christian states. A point of debate within the church related to the issue of the common Catholic teaching on slavery, in the main founded on Roman civil law, and if it could be subject to change. In 1888, Pope Leo XIII issued a letter to the Bishops of Brazil, In plurimis, and another in 1890, Catholicae Ecclesiae (On Slavery In The Missions). In both these letters the Pope singled out for praise twelve previous Popes who had made determined efforts to abolish slavery. Maxwell (1975) notes that Leo did not make mention of conciliar or Papal documents, nor canons of the general Church Law that had previously sanctioned slavery. Five of the Popes praised by Leo issued documents that authorized enslavement as an institution, as a penalty for ecclesiastical offences, or when arising through war. No distinction is made in Pope Leo’s letters between "just" and "unjust" forms of slavery and has therefore been interpreted as a condemnation of slavery as an institution, though other Catholic moral theologians continued to teach up until the middle of twentieth century that slavery was not intrinsically morally wrong. C. R. Boxer deals with this in chapter 1 of his book The Church Militant and Iberian Expansion, 1440–1770 (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978): see note 45 (p. 126), where he refers to sources not cited by Maxwell.

United States

Two slaveholding states, Maryland and Louisiana, had large contingents of Catholic residents; however both states had also the largest numbers of former enslaved persons who were freed. Archbishop of Baltimore, John Carroll, had two black servants - one free and one enslaved. (He is also alleged to have been related to a slave descendant, Sister Anne Marie Becraft.)

In 1820, the Jesuits had nearly 400 slaves on their Maryland plantations. The Society of Jesus owned a large number of enslaved individuals who worked on the community’s farms. Realizing that their properties were more profitable if rented out to tenant farmers rather that worked by enslaved people, the Jesuits began selling off their bondsmen in 1837. One notable example of this was the large sale of 272 slaves by the Jesuit Maryland Province in 1838.

Although Louisiana was one of the slaveholding states, it also had one of largest populations of formerly enslaved people in the United States. Most of the former bondsmen lived in New Orleans and the southern part of the state (the Catholic region of Louisiana). More than in other areas of the South, many free blacks in New Orleans were middle class and well-educated; many were property owners. Catholics only started to become a significant part of the overall US population in the 1840s with the arrival of poor Irish and Southern Italian immigrants who congregated in urban Northern and non-slaveholding areas.

Despite the issuance of In supremo apostolatus, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, to support slaveholding interests. Some American bishops interpreted In supremo as condemning only the slave trade and not slavery itself. Bishop John England of Charleston actually wrote several letters to the Secretary of State under President Van Buren explaining that the Pope, in In supremo, did not condemn slavery but only the slave trade.

In In supremo apostolatus, Pope Gregory XVI admonished and adjured "all believers in Christ, of whatsoever condition, that no one hereafter may dare unjustly to molest Indians, Blacks, or other men of this sort;...or to reduce them to slavery...". Catholic bishops in the Southern U.S. focused on the word "unjustly". They argued that the Pope did not condemn slavery if the enslaved individuals had been captured justly—that is, they were either criminals or prisoners of war. The bishops determined that this prohibition did not apply to slavery in the US.

Answering the charge that Catholics were widely supporting the abolitionist movement, Bishop England noted that Gregory XVI was condemning only the slave trade and not slavery itself, especially as it existed in the United States. To prove his opinion, England had In supremo translated and published in his diocesan newspaper, The United States Catholic Miscellany, and even went so far as to write a series of 18 extensive letters to John Forsyth, the Secretary of State under President Martin Van Buren, to explain how he and most of the other American bishops interpreted In supremo apostolatus.

Daniel O'Connell, the Roman Catholic leader of the Irish in Ireland, supported the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and in America. Garrison recruited him to the cause of American abolitionism. O'Connell, the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond, and the temperance priest Theobald Mathew organized a petition with 60,000 signatures urging the Irish of the United States to support abolition. O'Connell also spoke in the United States for abolition. One outspoken critic of slavery was Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of Cincinnati, Ohio. In an 1863 Catholic Telegraph editorial Purcell wrote:

- "When the slave power predominates, religion is nominal. There is no life in it. It is the hard-working laboring man who builds the church, the school house, the orphan asylum, not the slaveholder, as a general rule. Religion flourishes in a slave state only in proportion to its intimacy with a free state, or as it is adjacent to it."

Between 1821 and 1836 when Mexico opened up its territory of Texas to American settlers, many of the settlers had problems bringing enslaved people into Catholic Mexico (which did not allow slavery).

During the Civil War, Bishop Patrick Neeson Lynch was named by The Confederacy President Jefferson Davis to be its delegate to the Holy See which maintained diplomatic relations in the name of the Papal States. Despite Bishop Lynch’s mission, and an earlier mission by A. Dudley Mann, the Vatican never recognized the Confederacy, and the Pope received Bishop Lynch only his ecclesiastical capacity.

William T. Sherman, a prominent Union General during the Civil War, was a baptized Catholic whose son became a priest, but who disavowed Catholicism after the war ended. Sherman’s military campaigns of 1864 and 1865 freed many enslaved people, who joined his marches through Georgia and the Carolinas by the tens of thousands, although his personal views on the rights of African Americans and the morality of slavery appear to have been somewhat more nuanced. George Meade, the Union General who was victorious at the Battle of Gettysburg, was baptized as a Catholic in infancy, though it is not clear whether he practiced that religion later in his life.

Concerning Ethiopians

In 1866 the Holy Office issued an Instruction (signed by Pope Pius IX) in reply to questions from a vicar apostolic of the Galla tribe in Ethiopia: ". . . slavery itself, considered as such in its essential nature, is not at all contrary to the natural and divine law, and there can be several just titles of slavery and these are referred to by approved theologians and commentators of the sacred canons. For the sort of ownership which a slave-owner has over a slave is understood as nothing other than the perpetual right of disposing of the work of a slave for one’s own benefit - services which it is right for one human being to provide for another. From this it follows that it is not contrary to the natural and divine law for a slave to be sold, bought, exchanged or donated, provided that in this sale, purchase, exchange or gift, the due conditions are strictly observed which the approved authors likewise describe and explain. Among these conditions the most important ones are that the purchaser should carefully examine whether the slave who is put up for sale has been justly or unjustly deprived of his liberty, and that the vendor should do nothing which might endanger the life, virtue or Catholic faith of the slave who is to be transferred to another's possession."

Some commentators suggest that the statement was triggered by the passage of the 13th Amendment in the US. Others claim that the document referred only to a "particular situation in Africa to have slaves under certain conditions," and not necessarily to the situation in the U.S. Maxwell (1975) writes that this document sets out a contemporary theological exposition of morally legitimate slavery and slave trading.

20th century and 21st century

The Vatican II document Gaudium et spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World) stated: "Whatever violates the integrity of the human person, such as mutilation, torture...whatever insults human dignity, subhuman living conditions, arbitrary imprisonment, deportation, slavery ... the selling of women and children; as well as disgraceful working conditions, where men are treated as mere tools for profit, rather than as free and responsible persons; all these things and others of their like are infamies indeed ... they are a supreme dishonor to the Creator." John Paul II declared: “It is fitting to confess in all truth and humility this sin of man against man, this sin of man against God.”

Nevertheless, institutions in the Catholic Church continued to be linked with forced labour throughout the 20th century. In Ireland, up to 30,000 women were subjected to forced labour at those Magdalene Laundries ran by Catholics from 1922 to 1996. Magdalene asylums in Ireland were not limited to Catholics, however, and the Protestant Bethany Home has also suffered from abuses and faced criticism and has a Survivor’s group.

In 2002 Archbishop of Accra Charles G. Palmer-Buckle apologized on behalf of Africans for the part Africans played in the slave trade, and the apology was accepted by bishop John Ricard of Pensacola-Tallahassee.

Development of Church teaching

Although many authors argue that there has been a shift in Church teaching over the last two millennia from acceptance and toleration of slavery to opposition, other Catholic writers reject this claim, insisting that there has been no such change in the Magisterium. One reason for this insistence is that authors who argue that the Magisterium has changed have pointed to this purported shift in teaching as setting a precedent that Church teaching has changed to be compatible with changes in social mores and morality.

Cardinal Avery Dulles makes the following observations about the Catholic Church and the institution of slavery

- For many centuries the Church was part of a slave-holding society.

- The popes themselves held slaves, including at times hundreds of Muslim captives to man their galleys.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Luther, and Calvin were all Augustinian on this point. Although the subjection of one person to another (servitus) was not part of the primary intention of the natural law, St. Thomas taught, it was appropriate and socially useful in a world impaired by original sin.

- No Father or Doctor of the Church was an unqualified abolitionist.

- No pope or council ever made a sweeping condemnation of slavery as such.

- But they constantly sought to alleviate the evils of slavery and repeatedly denounced the mass enslavement of conquered populations and the infamous slave trade, thereby undermining slavery at its sources.

In a modern work that denies any fundamental change in the church’s teaching over the centuries, Father Joel Panzer writes:

The development of [the Church’s teaching regarding slavery] over the span of nearly five centuries was occasioned by the unique and illicit form of servitude that accompanied the Age of Discovery. The just titles to servitude were not rejected by the Church, but rather were tolerated for many reasons. This in no way invalidates the clear and consistent teaching against the unjust slavery that came to prevail in Africa and the Western Hemisphere, first in Central and South America and then in the United States, for approximately four centuries.

The "servitude" that Panzer describes allows, subject to certain conditions, the buying, selling and exchange of other human beings as described in the Holy Office decree of 1866 and he believes this has been the constant teaching of Popes down through the ages. Maxwell (1975) argues against a very rigid understanding of Papal texts, and their immutability, noting that torture was also once sanctioned by Papal decree. Pope John Paul II in 1995 "in the name of the whole Church" forbade the selling of women and children. In a book edited by Charles Curran, Diana Hayes also concludes that there was a change in the church’s teaching, which she places in the 1880s.

Vic Biorseth argues that "In all of recorded history, there is no such thing as a matter of faith and morals on which the Holy Roman Catholic Church has ever changed its teaching." Maxwell (1975) asserts that it has been difficult for Catholic historians to write impartially on this subject. By way of example he notes texts of Pope Leo XIII who singled out for praise twelve previous Popes who made every effort to end slavery. Maxwell then points out that five of the mentioned Popes actually authorized slavery but suggests the error could be due to the Popes' "ghost writers". Hugh Thomas, author of "The Slave Trade" is critical of the New Catholic Encyclopedia through its "misleading" account of Papal condemnation of slavery. Maxwell (1975) describes the situation as the historical "whitewashing" of the Church’s involvement in slavery.

Father John Francis Maxwell in 1975 published "Slavery and the Catholic Church: The history of Catholic teaching concerning the moral legitimacy of the institution of slavery", a book that was the product of seven years research. It recorded the instances where slavery was sanctioned by Councils and Popes and also censures and prohibitions that have been recorded throughout the history of the Church. He explains that what appears to the layman, not familiar with the intricacies of Church teaching and law, to be contradictory teaching, often involving the same Pope, is actually only a reflection of the common and longstanding concept of permissible "just slavery", and "unjust slavery" which was subject to condemnation. He shows by numerous examples from Council and Papal documents that “just slavery” was always an acceptable part of Catholic teaching right up until the end of the 19th century when the first steps were taken to place all forms of slavery under the ban. Since "just" slavery had been allowed by previous Councils and Popes he saw the declaration of slavery as an unconditional “infamy” in the Second Vatican Council pastoral constitution "Gaudium et spes" as a correction to what had been previously allowed, but not promulgated as infallible teaching. Dulles disagrees, different types of servitude being distinguished.

Pope John Paul II in his encyclical "Evangelium Vitae" (1995), when repeating the list of infamies that included slavery, prefaced the passage in "Gaudium es spes" with " ..Thirty years later, taking up the words of the Council and with the same forcefulness I repeat that condemnation in the name of the whole Church, certain that I am interpreting the genuine sentiment of every upright conscience."