Linear algebra is the branch of mathematics concerning linear equations such as:

linear maps such as:

and their representations in vector spaces and through matrices.

Linear algebra is central to almost all areas of mathematics. For instance, linear algebra is fundamental in modern presentations of geometry, including for defining basic objects such as lines, planes and rotations. Also, functional analysis, a branch of mathematical analysis, may be viewed as the application of linear algebra to spaces of functions.

Linear algebra is also used in most sciences and fields of engineering, because it allows modeling many natural phenomena, and computing efficiently with such models. For nonlinear systems, which cannot be modeled with linear algebra, it is often used for dealing with first-order approximations, using the fact that the differential of a multivariate function at a point is the linear map that best approximates the function near that point.

History

The procedure (using counting rods) for solving simultaneous linear equations now called Gaussian elimination appears in the ancient Chinese mathematical text Chapter Eight: Rectangular Arrays of The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art. Its use is illustrated in eighteen problems, with two to five equations.

Systems of linear equations arose in Europe with the introduction in 1637 by René Descartes of coordinates in geometry. In fact, in this new geometry, now called Cartesian geometry, lines and planes are represented by linear equations, and computing their intersections amounts to solving systems of linear equations.

The first systematic methods for solving linear systems used determinants, first considered by Leibniz in 1693. In 1750, Gabriel Cramer used them for giving explicit solutions of linear systems, now called Cramer's rule. Later, Gauss further described the method of elimination, which was initially listed as an advancement in geodesy.

In 1844 Hermann Grassmann published his "Theory of Extension" which included foundational new topics of what is today called linear algebra. In 1848, James Joseph Sylvester introduced the term matrix, which is Latin for womb.

Linear algebra grew with ideas noted in the complex plane. For instance, two numbers w and z in have a difference w – z, and the line segments wz and 0(w − z) are of the same length and direction. The segments are equipollent. The four-dimensional system of quaternions was started in 1843. The term vector was introduced as v = xi + yj + zk representing a point in space. The quaternion difference p – q also produces a segment equipollent to pq. Other hypercomplex number systems also used the idea of a linear space with a basis.

Arthur Cayley introduced matrix multiplication and the inverse matrix in 1856, making possible the general linear group. The mechanism of group representation became available for describing complex and hypercomplex numbers. Crucially, Cayley used a single letter to denote a matrix, thus treating a matrix as an aggregate object. He also realized the connection between matrices and determinants, and wrote "There would be many things to say about this theory of matrices which should, it seems to me, precede the theory of determinants".

Benjamin Peirce published his Linear Associative Algebra (1872), and his son Charles Sanders Peirce extended the work later.

The telegraph required an explanatory system, and the 1873 publication of A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism instituted a field theory of forces and required differential geometry for expression. Linear algebra is flat differential geometry and serves in tangent spaces to manifolds. Electromagnetic symmetries of spacetime are expressed by the Lorentz transformations, and much of the history of linear algebra is the history of Lorentz transformations.

The first modern and more precise definition of a vector space was introduced by Peano in 1888; by 1900, a theory of linear transformations of finite-dimensional vector spaces had emerged. Linear algebra took its modern form in the first half of the twentieth century, when many ideas and methods of previous centuries were generalized as abstract algebra. The development of computers led to increased research in efficient algorithms for Gaussian elimination and matrix decompositions, and linear algebra became an essential tool for modelling and simulations.

Vector spaces

Until the 19th century, linear algebra was introduced through systems of linear equations and matrices. In modern mathematics, the presentation through vector spaces is generally preferred, since it is more synthetic, more general (not limited to the finite-dimensional case), and conceptually simpler, although more abstract.

A vector space over a field F (often the field of the real numbers) is a set V equipped with two binary operations satisfying the following axioms. Elements of V are called vectors, and elements of F are called scalars. The first operation, vector addition, takes any two vectors v and w and outputs a third vector v + w. The second operation, scalar multiplication, takes any scalar a and any vector v and outputs a new vector av. The axioms that addition and scalar multiplication must satisfy are the following. (In the list below, u, v and w are arbitrary elements of V, and a and b are arbitrary scalars in the field F.)

Axiom Signification Associativity of addition u + (v + w) = (u + v) + w Commutativity of addition u + v = v + u Identity element of addition There exists an element 0 in V, called the zero vector (or simply zero), such that v + 0 = v for all v in V. Inverse elements of addition For every v in V, there exists an element −v in V, called the additive inverse of v, such that v + (−v) = 0 Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to vector addition a(u + v) = au + av Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to field addition (a + b)v = av + bv Compatibility of scalar multiplication with field multiplication a(bv) = (ab)v Identity element of scalar multiplication 1v = v, where 1 denotes the multiplicative identity of F.

The first four axioms mean that V is an abelian group under addition.

An element of a specific vector space may have various nature; for example, it could be a sequence, a function, a polynomial or a matrix. Linear algebra is concerned with those properties of such objects that are common to all vector spaces.

Linear maps

Linear maps are mappings between vector spaces that preserve the vector-space structure. Given two vector spaces V and W over a field F, a linear map (also called, in some contexts, linear transformation or linear mapping) is a map

that is compatible with addition and scalar multiplication, that is

for any vectors u,v in V and scalar a in F.

This implies that for any vectors u, v in V and scalars a, b in F, one has

When V = W are the same vector space, a linear map T : V → V is also known as a linear operator on V.

A bijective linear map between two vector spaces (that is, every vector from the second space is associated with exactly one in the first) is an isomorphism. Because an isomorphism preserves linear structure, two isomorphic vector spaces are "essentially the same" from the linear algebra point of view, in the sense that they cannot be distinguished by using vector space properties. An essential question in linear algebra is testing whether a linear map is an isomorphism or not, and, if it is not an isomorphism, finding its range (or image) and the set of elements that are mapped to the zero vector, called the kernel of the map. All these questions can be solved by using Gaussian elimination or some variant of this algorithm.

Subspaces, span, and basis

The study of those subsets of vector spaces that are in themselves vector spaces under the induced operations is fundamental, similarly as for many mathematical structures. These subsets are called linear subspaces. More precisely, a linear subspace of a vector space V over a field F is a subset W of V such that u + v and au are in W, for every u, v in W, and every a in F. (These conditions suffice for implying that W is a vector space.)

For example, given a linear map T : V → W, the image T(V) of V, and the inverse image T−1(0) of 0 (called kernel or null space), are linear subspaces of W and V, respectively.

Another important way of forming a subspace is to consider linear combinations of a set S of vectors: the set of all sums

where v1, v2, ..., vk are in S, and a1, a2, ..., ak are in F form a linear subspace called the span of S. The span of S is also the intersection of all linear subspaces containing S. In other words, it is the smallest (for the inclusion relation) linear subspace containing S.

A set of vectors is linearly independent if none is in the span of the others. Equivalently, a set S of vectors is linearly independent if the only way to express the zero vector as a linear combination of elements of S is to take zero for every coefficient ai.

A set of vectors that spans a vector space is called a spanning set or generating set. If a spanning set S is linearly dependent (that is not linearly independent), then some element w of S is in the span of the other elements of S, and the span would remain the same if one remove w from S. One may continue to remove elements of S until getting a linearly independent spanning set. Such a linearly independent set that spans a vector space V is called a basis of V. The importance of bases lies in the fact that they are simultaneously minimal generating sets and maximal independent sets. More precisely, if S is a linearly independent set, and T is a spanning set such that S ⊆ T, then there is a basis B such that S ⊆ B ⊆ T.

Any two bases of a vector space V have the same cardinality, which is called the dimension of V; this is the dimension theorem for vector spaces. Moreover, two vector spaces over the same field F are isomorphic if and only if they have the same dimension.

If any basis of V (and therefore every basis) has a finite number of elements, V is a finite-dimensional vector space. If U is a subspace of V, then dim U ≤ dim V. In the case where V is finite-dimensional, the equality of the dimensions implies U = V.

If U1 and U2 are subspaces of V, then

where U1 + U2 denotes the span of U1 ∪ U2.

Matrices

Matrices allow explicit manipulation of finite-dimensional vector spaces and linear maps. Their theory is thus an essential part of linear algebra.

Let V be a finite-dimensional vector space over a field F, and (v1, v2, ..., vm) be a basis of V (thus m is the dimension of V). By definition of a basis, the map

is a bijection from Fm, the set of the sequences of m elements of F, onto V. This is an isomorphism of vector spaces, if Fm is equipped of its standard structure of vector space, where vector addition and scalar multiplication are done component by component.

This isomorphism allows representing a vector by its inverse image under this isomorphism, that is by the coordinates vector (a1, ..., am) or by the column matrix

If W is another finite dimensional vector space (possibly the same), with a basis (w1, ..., wn), a linear map f from W to V is well defined by its values on the basis elements, that is (f(w1), ..., f(wn)). Thus, f is well represented by the list of the corresponding column matrices. That is, if

for j = 1, ..., n, then f is represented by the matrix

with m rows and n columns.

Matrix multiplication is defined in such a way that the product of two matrices is the matrix of the composition of the corresponding linear maps, and the product of a matrix and a column matrix is the column matrix representing the result of applying the represented linear map to the represented vector. It follows that the theory of finite-dimensional vector spaces and the theory of matrices are two different languages for expressing exactly the same concepts.

Two matrices that encode the same linear transformation in different bases are called similar. It can be proved that two matrices are similar if and only if one can transform one into the other by elementary row and column operations. For a matrix representing a linear map from W to V, the row operations correspond to change of bases in V and the column operations correspond to change of bases in W. Every matrix is similar to an identity matrix possibly bordered by zero rows and zero columns. In terms of vector spaces, this means that, for any linear map from W to V, there are bases such that a part of the basis of W is mapped bijectively on a part of the basis of V, and that the remaining basis elements of W, if any, are mapped to zero. Gaussian elimination is the basic algorithm for finding these elementary operations, and proving these results.

Linear systems

A finite set of linear equations in a finite set of variables, for example, x1, x2, ..., xn, or x, y, ..., z is called a system of linear equations or a linear system.

Systems of linear equations form a fundamental part of linear algebra. Historically, linear algebra and matrix theory has been developed for solving such systems. In the modern presentation of linear algebra through vector spaces and matrices, many problems may be interpreted in terms of linear systems.

For example, let

-

(S)

be a linear system.

To such a system, one may associate its matrix

and its right member vector

Let T be the linear transformation associated to the matrix M. A solution of the system (S) is a vector

such that

that is an element of the preimage of v by T.

Let (S′) be the associated homogeneous system, where the right-hand sides of the equations are put to zero:

-

(S′)

The solutions of (S′) are exactly the elements of the kernel of T or, equivalently, M.

The Gaussian-elimination consists of performing elementary row operations on the augmented matrix

for putting it in reduced row echelon form. These row operations do not change the set of solutions of the system of equations. In the example, the reduced echelon form is

showing that the system (S) has the unique solution

It follows from this matrix interpretation of linear systems that the same methods can be applied for solving linear systems and for many operations on matrices and linear transformations, which include the computation of the ranks, kernels, matrix inverses.

Endomorphisms and square matrices

A linear endomorphism is a linear map that maps a vector space V to itself. If V has a basis of n elements, such an endomorphism is represented by a square matrix of size n.

With respect to general linear maps, linear endomorphisms and square matrices have some specific properties that make their study an important part of linear algebra, which is used in many parts of mathematics, including geometric transformations, coordinate changes, quadratic forms, and many other part of mathematics.

Determinant

The determinant of a square matrix A is defined to be

where Sn is the group of all permutations of n elements, σ is a permutation, and (−1)σ the parity of the permutation. A matrix is invertible if and only if the determinant is invertible (i.e., nonzero if the scalars belong to a field).

Cramer's rule is a closed-form expression, in terms of determinants, of the solution of a system of n linear equations in n unknowns. Cramer's rule is useful for reasoning about the solution, but, except for n = 2 or 3, it is rarely used for computing a solution, since Gaussian elimination is a faster algorithm.

The determinant of an endomorphism is the determinant of the matrix representing the endomorphism in terms of some ordered basis. This definition makes sense, since this determinant is independent of the choice of the basis.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

If f is a linear endomorphism of a vector space V over a field F, an eigenvector of f is a nonzero vector v of V such that f(v) = av for some scalar a in F. This scalar a is an eigenvalue of f.

If the dimension of V is finite, and a basis has been chosen, f and v may be represented, respectively, by a square matrix M and a column matrix z; the equation defining eigenvectors and eigenvalues becomes

Using the identity matrix I, whose entries are all zero, except those of the main diagonal, which are equal to one, this may be rewritten

As z is supposed to be nonzero, this means that M – aI is a singular matrix, and thus that its determinant det (M − aI) equals zero. The eigenvalues are thus the roots of the polynomial

If V is of dimension n, this is a monic polynomial of degree n, called the characteristic polynomial of the matrix (or of the endomorphism), and there are, at most, n eigenvalues.

If a basis exists that consists only of eigenvectors, the matrix of f on this basis has a very simple structure: it is a diagonal matrix such that the entries on the main diagonal are eigenvalues, and the other entries are zero. In this case, the endomorphism and the matrix are said to be diagonalizable. More generally, an endomorphism and a matrix are also said diagonalizable, if they become diagonalizable after extending the field of scalars. In this extended sense, if the characteristic polynomial is square-free, then the matrix is diagonalizable.

A symmetric matrix is always diagonalizable. There are non-diagonalizable matrices, the simplest being

(it cannot be diagonalizable since its square is the zero matrix, and the square of a nonzero diagonal matrix is never zero).

When an endomorphism is not diagonalizable, there are bases on which it has a simple form, although not as simple as the diagonal form. The Frobenius normal form does not need of extending the field of scalars and makes the characteristic polynomial immediately readable on the matrix. The Jordan normal form requires to extend the field of scalar for containing all eigenvalues, and differs from the diagonal form only by some entries that are just above the main diagonal and are equal to 1.

Duality

A linear form is a linear map from a vector space V over a field F to the field of scalars F, viewed as a vector space over itself. Equipped by pointwise addition and multiplication by a scalar, the linear forms form a vector space, called the dual space of V, and usually denoted V* or V′.

If v1, ..., vn is a basis of V (this implies that V is finite-dimensional), then one can define, for i = 1, ..., n, a linear map vi* such that vi*(vi) = 1 and vi*(vj) = 0 if j ≠ i. These linear maps form a basis of V*, called the dual basis of v1, ..., vn. (If V is not finite-dimensional, the vi* may be defined similarly; they are linearly independent, but do not form a basis.)

For v in V, the map

is a linear form on V*. This defines the canonical linear map from V into (V*)*, the dual of V*, called the bidual of V. This canonical map is an isomorphism if V is finite-dimensional, and this allows identifying V with its bidual. (In the infinite dimensional case, the canonical map is injective, but not surjective.)

There is thus a complete symmetry between a finite-dimensional vector space and its dual. This motivates the frequent use, in this context, of the bra–ket notation

for denoting f(x).

Dual map

Let

be a linear map. For every linear form h on W, the composite function h ∘ f is a linear form on V. This defines a linear map

between the dual spaces, which is called the dual or the transpose of f.

If V and W are finite dimensional, and M is the matrix of f in terms of some ordered bases, then the matrix of f* over the dual bases is the transpose MT of M, obtained by exchanging rows and columns.

If elements of vector spaces and their duals are represented by column vectors, this duality may be expressed in bra–ket notation by

For highlighting this symmetry, the two members of this equality are sometimes written

Inner-product spaces

Besides these basic concepts, linear algebra also studies vector spaces with additional structure, such as an inner product. The inner product is an example of a bilinear form, and it gives the vector space a geometric structure by allowing for the definition of length and angles. Formally, an inner product is a map

that satisfies the following three axioms for all vectors u, v, w in V and all scalars a in F:

- Conjugate symmetry:

- In , it is symmetric.

- Linearity in the first argument:

- Positive-definiteness:

- with equality only for v = 0.

We can define the length of a vector v in V by

and we can prove the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality:

In particular, the quantity

and so we can call this quantity the cosine of the angle between the two vectors.

Two vectors are orthogonal if ⟨u, v⟩ = 0. An orthonormal basis is a basis where all basis vectors have length 1 and are orthogonal to each other. Given any finite-dimensional vector space, an orthonormal basis could be found by the Gram–Schmidt procedure. Orthonormal bases are particularly easy to deal with, since if v = a1 v1 + ⋯ + an vn, then

The inner product facilitates the construction of many useful concepts. For instance, given a transform T, we can define its Hermitian conjugate T* as the linear transform satisfying

If T satisfies TT* = T*T, we call T normal. It turns out that normal matrices are precisely the matrices that have an orthonormal system of eigenvectors that span V.

Relationship with geometry

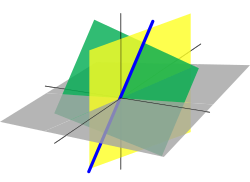

There is a strong relationship between linear algebra and geometry, which started with the introduction by René Descartes, in 1637, of Cartesian coordinates. In this new (at that time) geometry, now called Cartesian geometry, points are represented by Cartesian coordinates, which are sequences of three real numbers (in the case of the usual three-dimensional space). The basic objects of geometry, which are lines and planes are represented by linear equations. Thus, computing intersections of lines and planes amounts to solving systems of linear equations. This was one of the main motivations for developing linear algebra.

Most geometric transformation, such as translations, rotations, reflections, rigid motions, isometries, and projections transform lines into lines. It follows that they can be defined, specified and studied in terms of linear maps. This is also the case of homographies and Möbius transformations, when considered as transformations of a projective space.

Until the end of 19th century, geometric spaces were defined by axioms relating points, lines and planes (synthetic geometry). Around this date, it appeared that one may also define geometric spaces by constructions involving vector spaces (see, for example, Projective space and Affine space). It has been shown that the two approaches are essentially equivalent. In classical geometry, the involved vector spaces are vector spaces over the reals, but the constructions may be extended to vector spaces over any field, allowing considering geometry over arbitrary fields, including finite fields.

Presently, most textbooks, introduce geometric spaces from linear algebra, and geometry is often presented, at elementary level, as a subfield of linear algebra.

Usage and applications

Linear algebra is used in almost all areas of mathematics, thus making it relevant in almost all scientific domains that use mathematics. These applications may be divided into several wide categories.

Geometry of ambient space

The modeling of ambient space is based on geometry. Sciences concerned with this space use geometry widely. This is the case with mechanics and robotics, for describing rigid body dynamics; geodesy for describing Earth shape; perspectivity, computer vision, and computer graphics, for describing the relationship between a scene and its plane representation; and many other scientific domains.

In all these applications, synthetic geometry is often used for general descriptions and a qualitative approach, but for the study of explicit situations, one must compute with coordinates. This requires the heavy use of linear algebra.

Functional analysis

Functional analysis studies function spaces. These are vector spaces with additional structure, such as Hilbert spaces. Linear algebra is thus a fundamental part of functional analysis and its applications, which include, in particular, quantum mechanics (wave functions).

Study of complex systems

Most physical phenomena are modeled by partial differential equations. To solve them, one usually decomposes the space in which the solutions are searched into small, mutually interacting cells. For linear systems this interaction involves linear functions. For nonlinear systems, this interaction is often approximated by linear functions. In both cases, very large matrices are generally involved. Weather forecasting is a typical example, where the whole Earth atmosphere is divided in cells of, say, 100 km of width and 100 m of height.

Scientific computation

Nearly all scientific computations involve linear algebra. Consequently, linear algebra algorithms have been highly optimized. BLAS and LAPACK are the best known implementations. For improving efficiency, some of them configure the algorithms automatically, at run time, for adapting them to the specificities of the computer (cache size, number of available cores, ...).

Some processors, typically graphics processing units (GPU), are designed with a matrix structure, for optimizing the operations of linear algebra.

Extensions and generalizations

This section presents several related topics that do not appear generally in elementary textbooks on linear algebra, but are commonly considered, in advanced mathematics, as parts of linear algebra.

Module theory

The existence of multiplicative inverses in fields is not involved in the axioms defining a vector space. One may thus replace the field of scalars by a ring R, and this gives a structure called module over R, or R-module.

The concepts of linear independence, span, basis, and linear maps (also called module homomorphisms) are defined for modules exactly as for vector spaces, with the essential difference that, if R is not a field, there are modules that do not have any basis. The modules that have a basis are the free modules, and those that are spanned by a finite set are the finitely generated modules. Module homomorphisms between finitely generated free modules may be represented by matrices. The theory of matrices over a ring is similar to that of matrices over a field, except that determinants exist only if the ring is commutative, and that a square matrix over a commutative ring is invertible only if its determinant has a multiplicative inverse in the ring.

Vector spaces are completely characterized by their dimension (up to an isomorphism). In general, there is not such a complete classification for modules, even if one restricts oneself to finitely generated modules. However, every module is a cokernel of a homomorphism of free modules.

Modules over the integers can be identified with abelian groups, since the multiplication by an integer may identified to a repeated addition. Most of the theory of abelian groups may be extended to modules over a principal ideal domain. In particular, over a principal ideal domain, every submodule of a free module is free, and the fundamental theorem of finitely generated abelian groups may be extended straightforwardly to finitely generated modules over a principal ring.

There are many rings for which there are algorithms for solving linear equations and systems of linear equations. However, these algorithms have generally a computational complexity that is much higher than the similar algorithms over a field. For more details, see Linear equation over a ring.

Multilinear algebra and tensors

In multilinear algebra, one considers multivariable linear transformations, that is, mappings that are linear in each of a number of different variables. This line of inquiry naturally leads to the idea of the dual space, the vector space V* consisting of linear maps f : V → F where F is the field of scalars. Multilinear maps T : Vn → F can be described via tensor products of elements of V*.

If, in addition to vector addition and scalar multiplication, there is a bilinear vector product V × V → V, the vector space is called an algebra; for instance, associative algebras are algebras with an associate vector product (like the algebra of square matrices, or the algebra of polynomials).

Topological vector spaces

Vector spaces that are not finite dimensional often require additional structure to be tractable. A normed vector space is a vector space along with a function called a norm, which measures the "size" of elements. The norm induces a metric, which measures the distance between elements, and induces a topology, which allows for a definition of continuous maps. The metric also allows for a definition of limits and completeness – a metric space that is complete is known as a Banach space. A complete metric space along with the additional structure of an inner product (a conjugate symmetric sesquilinear form) is known as a Hilbert space, which is in some sense a particularly well-behaved Banach space. Functional analysis applies the methods of linear algebra alongside those of mathematical analysis to study various function spaces; the central objects of study in functional analysis are Lp spaces, which are Banach spaces, and especially the L2 space of square integrable functions, which is the only Hilbert space among them. Functional analysis is of particular importance to quantum mechanics, the theory of partial differential equations, digital signal processing, and electrical engineering. It also provides the foundation and theoretical framework that underlies the Fourier transform and related methods.

![{\displaystyle M=\left[{\begin{array}{rrr}2&1&-1\\-3&-1&2\\-2&1&2\end{array}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc5140ca13be8f555186b8d57b6223a4ef2e1b0b)

![{\displaystyle \left[\!{\begin{array}{c|c}M&\mathbf {v} \end{array}}\!\right]=\left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}2&1&-1&8\\-3&-1&2&-11\\-2&1&2&-3\end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6a94bf6a98576cd520287535af3a6587376f9be8)

![{\displaystyle \left[\!{\begin{array}{c|c}M&\mathbf {v} \end{array}}\!\right]=\left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&0&0&2\\0&1&0&3\\0&0&1&-1\end{array}}\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6a99163495ae1cf328208d89cadcdf23397fba0)