From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Some trajectories of a

harmonic oscillator according to

Newton's laws of

classical mechanics (A–B), and according to the

Schrödinger equation of

quantum mechanics (C–H). In A–B, the particle (represented as a ball attached to a

spring)

oscillates back and forth. In C–H, some solutions to the Schrödinger

Equation are shown, where the horizontal axis is position, and the

vertical axis is the real part (blue) or imaginary part (red) of the

wavefunction. C, D, E, F, but not G, H, are

energy eigenstates. H is a

coherent state—a quantum state that approximates the classical trajectory.

The quantum harmonic oscillator is the quantum-mechanical analog of the classical harmonic oscillator. Because an arbitrary smooth potential can usually be approximated as a harmonic potential at the vicinity of a stable equilibrium point,

it is one of the most important model systems in quantum mechanics.

Furthermore, it is one of the few quantum-mechanical systems for which

an exact, analytical solution is known.

One-dimensional harmonic oscillator

Hamiltonian and energy eigenstates

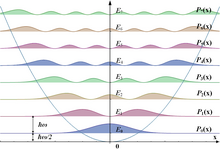

Wavefunction representations for the first eight bound eigenstates, n = 0 to 7. The horizontal axis shows the position x.

Corresponding probability densities.

The Hamiltonian of the particle is:

where

m is the particle's mass,

k is the force constant,

is the

angular frequency of the oscillator,

is the

position operator (given by

x in the coordinate basis), and

is the

momentum operator (given by

in the coordinate basis). The first term in the Hamiltonian represents

the kinetic energy of the particle, and the second term represents its

potential energy, as in

Hooke's law.

One may write the time-independent Schrödinger equation,

where

E denotes a to-be-determined real number that will specify a time-independent

energy level, or

eigenvalue, and the solution

|ψ⟩ denotes that level's energy

eigenstate.

One may solve the differential equation representing this eigenvalue problem in the coordinate basis, for the wave function ⟨x|ψ⟩ = ψ(x), using a spectral method. It turns out that there is a family of solutions. In this basis, they amount to Hermite functions,

The functions Hn are the physicists' Hermite polynomials,

The corresponding energy levels are

This energy spectrum is noteworthy for three reasons. First,

the energies are quantized, meaning that only discrete energy values

(integer-plus-half multiples of ħω)

are possible; this is a general feature of quantum-mechanical systems

when a particle is confined. Second, these discrete energy levels are

equally spaced, unlike in the Bohr model of the atom, or the particle in a box. Third, the lowest achievable energy (the energy of the n = 0 state, called the ground state) is not equal to the minimum of the potential well, but ħω/2 above it; this is called zero-point energy.

Because of the zero-point energy, the position and momentum of the

oscillator in the ground state are not fixed (as they would be in a

classical oscillator), but have a small range of variance, in accordance

with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

The ground state probability density is concentrated at the

origin, which means the particle spends most of its time at the bottom

of the potential well, as one would expect for a state with little

energy. As the energy increases, the probability density peaks at the

classical "turning points", where the state's energy coincides with the

potential energy. (See the discussion below of the highly excited

states.) This is consistent with the classical harmonic oscillator, in

which the particle spends more of its time (and is therefore more likely

to be found) near the turning points, where it is moving the slowest.

The correspondence principle is thus satisfied. Moreover, special nondispersive wave packets, with minimum uncertainty, called coherent states oscillate very much like classical objects, as illustrated in the figure; they are not eigenstates of the Hamiltonian.

Ladder operator method

Probability densities |ψn(x)|2 for the bound eigenstates, beginning with the ground state (n = 0) at the bottom and increasing in energy toward the top. The horizontal axis shows the position x, and brighter colors represent higher probability densities.

The "ladder operator" method, developed by Paul Dirac,

allows extraction of the energy eigenvalues without directly solving

the differential equation. It is generalizable to more complicated

problems, notably in quantum field theory. Following this approach, we define the operators a and its adjoint a†,

Note these operators classically are exactly the

generators of normalized rotation in the phase space of

and

,

i.e they describe the forwards and backwards evolution in time of a classical harmonic oscillator.

These operators lead to the useful representation of  and

and  ,

,

The operator a is not Hermitian, since itself and its adjoint a† are not equal. The energy eigenstates |n⟩ (also known as Fock states), when operated on by these ladder operators, give

It is then evident that a†, in essence, appends a single quantum of energy to the oscillator, while a removes a quantum. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as "creation" and "annihilation" operators.

From the relations above, we can also define a number operator N, which has the following property:

The following commutators can be easily obtained by substituting the canonical commutation relation,

![{\displaystyle [a,a^{\dagger }]=1,\qquad [N,a^{\dagger }]=a^{\dagger },\qquad [N,a]=-a,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b7f6211ee3864fd384153296ee48bdef516ab516)

And the Hamilton operator can be expressed as

so the eigenstate of N is also the eigenstate of energy.

The commutation property yields

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}Na^{\dagger }|n\rangle &=\left(a^{\dagger }N+[N,a^{\dagger }]\right)|n\rangle \\&=\left(a^{\dagger }N+a^{\dagger }\right)|n\rangle \\&=(n+1)a^{\dagger }|n\rangle ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e945ca3ab4735997c76d05abebe434817147577)

and similarly,

This means that a acts on |n⟩ to produce, up to a multiplicative constant, |n–1⟩, and a† acts on |n⟩ to produce |n+1⟩. For this reason, a is called a annihilation operator ("lowering operator"), and a† a creation operator ("raising operator"). The two operators together are called ladder operators. In quantum field theory, a and a†

are alternatively called "annihilation" and "creation" operators

because they destroy and create particles, which correspond to our

quanta of energy.

Given any energy eigenstate, we can act on it with the lowering operator, a, to produce another eigenstate with ħω less energy. By repeated application of the lowering operator, it seems that we can produce energy eigenstates down to E = −∞. However, since

the smallest eigen-number is 0, and

In this case, subsequent applications of the lowering operator

will just produce zero kets, instead of additional energy eigenstates.

Furthermore, we have shown above that

Finally, by acting on |0⟩ with the raising operator and multiplying by suitable normalization factors, we can produce an infinite set of energy eigenstates

such that

which matches the energy spectrum given in the preceding section.

Arbitrary eigenstates can be expressed in terms of |0⟩,

Proof

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\langle n|aa^{\dagger }|n\rangle &=\langle n|\left([a,a^{\dagger }]+a^{\dagger }a\right)|n\rangle =\langle n|(N+1)|n\rangle =n+1\\\Rightarrow a^{\dagger }|n\rangle &={\sqrt {n+1}}|n+1\rangle \\\Rightarrow |n\rangle &={\frac {a^{\dagger }}{\sqrt {n}}}|n-1\rangle ={\frac {(a^{\dagger })^{2}}{\sqrt {n(n-1)}}}|n-2\rangle =\cdots ={\frac {(a^{\dagger })^{n}}{\sqrt {n!}}}|0\rangle .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f766bb9930d3712c4d7c72d895c69b4f9ee36a15)

Analytical questions

The

preceding analysis is algebraic, using only the commutation relations

between the raising and lowering operators. Once the algebraic analysis

is complete, one should turn to analytical questions. First, one should

find the ground state, that is, the solution of the equation  . In the position representation, this is the first-order differential equation

. In the position representation, this is the first-order differential equation

whose solution is easily found to be the Gaussian

Conceptually, it is important that there is only one solution of this

equation; if there were, say, two linearly independent ground states, we

would get two independent chains of eigenvectors for the harmonic

oscillator. Once the ground state is computed, one can show inductively

that the excited states are Hermite polynomials times the Gaussian

ground state, using the explicit form of the raising operator in the

position representation. One can also prove that, as expected from the

uniqueness of the ground state, the Hermite functions energy eigenstates

constructed by the ladder method form a

complete orthonormal set of functions.

Explicitly connecting with the previous section, the ground state |0⟩ in the position representation is determined by  ,

,

hence

so that

, and so on.

Natural length and energy scales

The

quantum harmonic oscillator possesses natural scales for length and

energy, which can be used to simplify the problem. These can be found by

nondimensionalization.

The result is that, if energy is measured in units of ħω and distance in units of √ħ/(mω), then the Hamiltonian simplifies to

while the energy eigenfunctions and eigenvalues simplify to Hermite functions and integers offset by a half,

where

Hn(x) are the

Hermite polynomials.

To avoid confusion, these "natural units" will mostly not

be adopted in this article. However, they frequently come in handy when

performing calculations, by bypassing clutter.

For example, the fundamental solution (propagator) of H − i∂t, the time-dependent Schrödinger operator for this oscillator, simply boils down to the Mehler kernel,

where

K(x,y;0) = δ(x − y). The most general solution for a given initial configuration

ψ(x,0) then is simply

Coherent states

Time evolution of the probability distribution (and phase, shown as color) of a coherent state with |α|=3.

The coherent states (also known as Glauber states) of the harmonic oscillator are special nondispersive wave packets, with minimum uncertainty σx σp = ℏ⁄2, whose observables' expectation values evolve like a classical system. They are eigenvectors of the annihilation operator, not the Hamiltonian, and form an overcomplete basis which consequentially lacks orthogonality.

The coherent states are indexed by α ∈ C and expressed in the |n⟩ basis as

Because  and via the Kermack-McCrae identity, the last form is equivalent to a unitary displacement operator acting on the ground state:

and via the Kermack-McCrae identity, the last form is equivalent to a unitary displacement operator acting on the ground state:  . The position space wave functions are

. The position space wave functions are

Since coherent states are not energy eigenstates, their time

evolution is not a simple shift in wavefunction phase. The time-evolved

states are, however, also coherent states but with phase-shifting

parameter α instead:  .

.

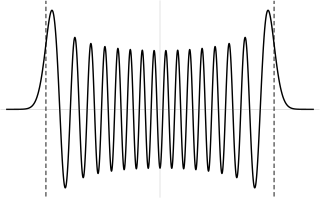

Highly excited states

Wavefunction (top) and probability density (bottom) for the n = 30

excited state of the quantum harmonic oscillator. Vertical dashed lines

indicate the classical turning points, while the dotted line represents

the classical probability density.

When n

is large, the eigenstates are localized into the classical allowed

region, that is, the region in which a classical particle with energy En

can move. The eigenstates are peaked near the turning points: the

points at the ends of the classically allowed region where the classical

particle changes direction. This phenomenon can be verified through asymptotics of the Hermite polynomials, and also through the WKB approximation.

The frequency of oscillation at x is proportional to the momentum p(x) of a classical particle of energy En and position x. Furthermore, the square of the amplitude (determining the probability density) is inversely proportional to p(x), reflecting the length of time the classical particle spends near x.

The system behavior in a small neighborhood of the turning point does

not have a simple classical explanation, but can be modeled using an Airy function.

Using properties of the Airy function, one may estimate the

probability of finding the particle outside the classically allowed

region, to be approximately

This is also given, asymptotically, by the integral

Phase space solutions

In the phase space formulation of quantum mechanics, eigenstates of the quantum harmonic oscillator in several different representations of the quasiprobability distribution can be written in closed form. The most widely used of these is for the Wigner quasiprobability distribution.

The Wigner quasiprobability distribution for the energy eigenstate |n⟩ is, in the natural units described above,

where

Ln are the

Laguerre polynomials. This example illustrates how the Hermite and Laguerre polynomials are

linked through the

Wigner map.

Meanwhile, the Husimi Q function of the harmonic oscillator eigenstates have an even simpler form. If we work in the natural units described above, we have

This claim can be verified using the

Segal–Bargmann transform. Specifically, since the

raising operator in the Segal–Bargmann representation is simply multiplication by

and the ground state is the constant function 1, the normalized harmonic oscillator states in this representation are simply

. At this point, we can appeal to the formula for the Husimi Q function in terms of the Segal–Bargmann transform.

N-dimensional isotropic harmonic oscillator

The one-dimensional harmonic oscillator is readily generalizable to N dimensions, where N = 1, 2, 3, …. In one dimension, the position of the particle was specified by a single coordinate, x. In N dimensions, this is replaced by N position coordinates, which we label x1, …, xN. Corresponding to each position coordinate is a momentum; we label these p1, …, pN. The canonical commutation relations between these operators are

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{[}x_{i},p_{j}{]}&=i\hbar \delta _{i,j}\\{[}x_{i},x_{j}{]}&=0\\{[}p_{i},p_{j}{]}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/22e7043822f15a1286e25a58789951f39e0585e5)

The Hamiltonian for this system is

As the form of this Hamiltonian makes clear, the N-dimensional harmonic oscillator is exactly analogous to N independent one-dimensional harmonic oscillators with the same mass and spring constant. In this case, the quantities x1, ..., xN would refer to the positions of each of the N particles. This is a convenient property of the r2 potential, which allows the potential energy to be separated into terms depending on one coordinate each.

This observation makes the solution straightforward. For a particular set of quantum numbers  the energy eigenfunctions for the N-dimensional oscillator are expressed in terms of the 1-dimensional eigenfunctions as:

the energy eigenfunctions for the N-dimensional oscillator are expressed in terms of the 1-dimensional eigenfunctions as:

In the ladder operator method, we define N sets of ladder operators,

By an analogous procedure to the one-dimensional case, we can then show that each of the ai and a†i operators lower and raise the energy by ℏω respectively. The Hamiltonian is

This Hamiltonian is invariant under the dynamic symmetry group

U(N) (the unitary group in

N dimensions), defined by

where

is an element in the defining matrix representation of

U(N).

The energy levels of the system are

![{\displaystyle E=\hbar \omega \left[(n_{1}+\cdots +n_{N})+{N \over 2}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2ecf3199f08b2da7ca91c54e0eb4785315151f6)

As in the one-dimensional case, the energy is quantized. The ground state energy is N times the one-dimensional ground energy, as we would expect using the analogy to N

independent one-dimensional oscillators. There is one further

difference: in the one-dimensional case, each energy level corresponds

to a unique quantum state. In N-dimensions, except for the ground state, the energy levels are degenerate, meaning there are several states with the same energy.

The degeneracy can be calculated relatively easily. As an example, consider the 3-dimensional case: Define n = n1 + n2 + n3. All states with the same n will have the same energy. For a given n, we choose a particular n1. Then n2 + n3 = n − n1. There are n − n1 + 1 possible pairs {n2, n3}. n2 can take on the values 0 to n − n1, and for each n2 the value of n3 is fixed. The degree of degeneracy therefore is:

Formula for general

N and

n [

gn being the dimension of the symmetric irreducible

n-th power representation of the unitary group

U(N)]:

The special case

N = 3, given above,

follows directly from this general equation. This is however, only

true for distinguishable particles, or one particle in

N dimensions (as dimensions are distinguishable). For the case of

N bosons in a one-dimension harmonic trap, the degeneracy scales as the number of ways to partition an integer

n using integers less than or equal to

N.

This arises due to the constraint of putting N quanta into a state ket where  and

and  , which are the same constraints as in integer partition.

, which are the same constraints as in integer partition.

Example: 3D isotropic harmonic oscillator

Schrödinger 3D spherical harmonic orbital solutions in 2D density plots; the

Mathematica source code that used for generating the plots is at the top

The Schrödinger equation for a particle in a spherically-symmetric

three-dimensional harmonic oscillator can be solved explicitly by

separation of variables; see this article for the present case. This procedure is analogous to the separation performed in the hydrogen-like atom problem, but with a different spherically symmetric potential

where

μ is the mass of the particle. Because

m will be used below for the magnetic quantum number, mass is indicated by

μ, instead of

m, as earlier in this article.

The solution reads

where

is a normalization constant;

is a normalization constant;  ;

;

are generalized Laguerre polynomials; The order k of the polynomial is a non-negative integer;

The energy eigenvalue is

The energy is usually described by the single

quantum number

Because k is a non-negative integer, for every even n we have ℓ = 0, 2, …, n − 2, n and for every odd n we have ℓ = 1, 3, …, n − 2, n . The magnetic quantum number m is an integer satisfying −ℓ ≤ m ≤ ℓ, so for every n and ℓ there are 2ℓ + 1 different quantum states, labeled by m . Thus, the degeneracy at level n is

where the sum starts from 0 or 1, according to whether

n

is even or odd.

This result is in accordance with the dimension formula above, and

amounts to the dimensionality of a symmetric representation of

SU(3), the relevant degeneracy group.

Applications

Harmonic oscillators lattice: phonons

We can extend the notion of a harmonic oscillator to a

one-dimensional lattice of many particles. Consider a one-dimensional

quantum mechanical harmonic chain of N identical atoms. This is the simplest quantum mechanical model of a lattice, and we will see how phonons arise from it. The formalism that we will develop for this model is readily generalizable to two and three dimensions.

As in the previous section, we denote the positions of the masses by x1, x2, …, as measured from their equilibrium positions (i.e. xi = 0 if the particle i is at its equilibrium position). In two or more dimensions, the xi are vector quantities. The Hamiltonian for this system is

where

m is the (assumed uniform) mass of each atom, and

xi and

pi are the position and

momentum operators for the

i

th atom and the sum is made over the nearest neighbors (nn). However,

it is customary to rewrite the Hamiltonian in terms of the

normal modes of the

wavevector rather than in terms of the particle coordinates so that one can work in the more convenient

Fourier space.

We introduce, then, a set of N "normal coordinates" Qk, defined as the discrete Fourier transforms of the xs, and N "conjugate momenta" Π defined as the Fourier transforms of the ps,

The quantity kn will turn out to be the wave number of the phonon, i.e. 2π divided by the wavelength. It takes on quantized values, because the number of atoms is finite.

This preserves the desired commutation relations in either real space or wave vector space

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left[x_{l},p_{m}\right]&=i\hbar \delta _{l,m}\\\left[Q_{k},\Pi _{k'}\right]&={1 \over N}\sum _{l,m}e^{ikal}e^{-ik'am}[x_{l},p_{m}]\\&={i\hbar \over N}\sum _{m}e^{iam(k-k')}=i\hbar \delta _{k,k'}\\\left[Q_{k},Q_{k'}\right]&=\left[\Pi _{k},\Pi _{k'}\right]=0~.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/74c7ccd4c0df07ca1880602ec1e747b06c2e11a3)

From the general result

it is easy to show, through elementary trigonometry, that the potential energy term is

where

The Hamiltonian may be written in wave vector space as

Note that the couplings between the position variables have been transformed away; if the Qs and Πs were hermitian (which they are not), the transformed Hamiltonian would describe N uncoupled harmonic oscillators.

The form of the quantization depends on the choice of boundary conditions; for simplicity, we impose periodic boundary conditions, defining the (N + 1)-th

atom as equivalent to the first atom. Physically, this corresponds to

joining the chain at its ends. The resulting quantization is

The upper bound to n comes from the minimum wavelength, which is twice the lattice spacing a, as discussed above.

The harmonic oscillator eigenvalues or energy levels for the mode ωk are

If we ignore the zero-point energy then the levels are evenly spaced at

So an exact amount of energy ħω, must be supplied to the harmonic oscillator lattice to push it to the next energy level. In analogy to the photon case when the electromagnetic field is quantised, the quantum of vibrational energy is called a phonon.

All quantum systems show wave-like and particle-like properties.

The particle-like properties of the phonon are best understood using the

methods of second quantization and operator techniques described elsewhere.

In the continuum limit, a→0, N→∞, while Na is held fixed. The canonical coordinates Qk devolve to the decoupled momentum modes of a scalar field,  , whilst the location index i (not the displacement dynamical variable) becomes the parameter x argument of the scalar field,

, whilst the location index i (not the displacement dynamical variable) becomes the parameter x argument of the scalar field,  .

.

Molecular vibrations

- The vibrations of a diatomic molecule are an example of a two-body version of the quantum harmonic oscillator. In this case, the angular frequency is given by

is the reduced mass and

is the reduced mass and  and

and  are the masses of the two atoms.

are the masses of the two atoms. - The Hooke's atom is a simple model of the helium atom using the quantum harmonic oscillator.

- Modelling phonons, as discussed above.

- A charge

with mass

with mass  in a uniform magnetic field

in a uniform magnetic field  is an example of a one-dimensional quantum harmonic oscillator: Landau quantization.

is an example of a one-dimensional quantum harmonic oscillator: Landau quantization.

![{\displaystyle [a,a^{\dagger }]=1,\qquad [N,a^{\dagger }]=a^{\dagger },\qquad [N,a]=-a,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b7f6211ee3864fd384153296ee48bdef516ab516)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}Na^{\dagger }|n\rangle &=\left(a^{\dagger }N+[N,a^{\dagger }]\right)|n\rangle \\&=\left(a^{\dagger }N+a^{\dagger }\right)|n\rangle \\&=(n+1)a^{\dagger }|n\rangle ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e945ca3ab4735997c76d05abebe434817147577)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\langle n|aa^{\dagger }|n\rangle &=\langle n|\left([a,a^{\dagger }]+a^{\dagger }a\right)|n\rangle =\langle n|(N+1)|n\rangle =n+1\\\Rightarrow a^{\dagger }|n\rangle &={\sqrt {n+1}}|n+1\rangle \\\Rightarrow |n\rangle &={\frac {a^{\dagger }}{\sqrt {n}}}|n-1\rangle ={\frac {(a^{\dagger })^{2}}{\sqrt {n(n-1)}}}|n-2\rangle =\cdots ={\frac {(a^{\dagger })^{n}}{\sqrt {n!}}}|0\rangle .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f766bb9930d3712c4d7c72d895c69b4f9ee36a15)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{[}x_{i},p_{j}{]}&=i\hbar \delta _{i,j}\\{[}x_{i},x_{j}{]}&=0\\{[}p_{i},p_{j}{]}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/22e7043822f15a1286e25a58789951f39e0585e5)

![{\displaystyle E=\hbar \omega \left[(n_{1}+\cdots +n_{N})+{N \over 2}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2ecf3199f08b2da7ca91c54e0eb4785315151f6)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left[x_{l},p_{m}\right]&=i\hbar \delta _{l,m}\\\left[Q_{k},\Pi _{k'}\right]&={1 \over N}\sum _{l,m}e^{ikal}e^{-ik'am}[x_{l},p_{m}]\\&={i\hbar \over N}\sum _{m}e^{iam(k-k')}=i\hbar \delta _{k,k'}\\\left[Q_{k},Q_{k'}\right]&=\left[\Pi _{k},\Pi _{k'}\right]=0~.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/74c7ccd4c0df07ca1880602ec1e747b06c2e11a3)