From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_world_order_(politics)The term "new world order" refers to a new period of history evidencing dramatic change in world political thought and the balance of power in international relations. Despite varied interpretations of this term, it is primarily associated with the ideological notion of world governance

only in the sense of new collective efforts to identify, understand, or

address global problems that go beyond the capacity of individual nation-states to solve.

The phrase "new world order" or similar language was used in the period toward the end of the First World War in relation to Woodrow Wilson's vision for international peace; Wilson called for a League of Nations to prevent aggression and conflict. The League of Nations failed, and neither Franklin Roosevelt nor Harry S. Truman used the phrase "new world order" much when speaking publicly on international peace and cooperation. Indeed, in some instances when Roosevelt used the phrase "new world order", or "new order in the world" it was to refer to Axis powers plans for world domination.

Truman speeches have phrases such as, "better world order", "peaceful

world order", "moral world order" and "world order based on law" but not

so much "new world order".

Although Roosevelt and Truman may have been hesitant to use the phrase,

commentators have applied the term retroactively to the order put in

place by the World War II victors including the United Nations and the Bretton Woods system as a "new world order."

The most widely discussed application of the phrase of recent times came at the end of the Cold War. Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush used the term to try to define the nature of the post-Cold War era and the spirit of great power cooperation that they hoped might materialize. Gorbachev's initial formulation was wide-ranging and idealistic, but his ability to press for it was severely limited by the internal crisis of the Soviet system.

In comparison, Bush's vision was not less circumscribed: "A hundred

generations have searched for this elusive path to peace, while a

thousand wars raged across the span of human endeavor. Today that new

world is struggling to be born, a world quite different from the one

we've known". However, given the new unipolar status of the United States, Bush's vision was realistic in saying that "there is no substitute for American leadership". The Gulf War

of 1991 was regarded as the first test of the new world order: "Now, we

can see a new world coming into view. A world in which there is the

very real prospect of a new world order. ... The Gulf War put this new

world to its first test".

Historical usage

The phrase "new world order" was explicitly used in connection with Woodrow Wilson's global zeitgeist during the period just after World War I during the formation of the League of Nations. "The war to end all wars"

had been a powerful catalyst in international politics, and many felt

the world could simply no longer operate as it once had. World War I had

been justified not only in terms of U.S. national interest,

but in moral terms—to "make the world safe for democracy". After the

war, Wilson argued for a new world order which transcended traditional

great power politics, instead emphasizing collective security, democracy

and self-determination. However, the United States Senate rejected membership of the League of Nations, which Wilson believed to be the key to a new world order. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge argued that American policy should be based on human nature "as it is, not as it ought to be". Nazi activist and future German leader Adolf Hitler also used the term in 1928.

The term fell from use when it became clear the League was not living

up to expectations and as a consequence was used very little during the

formation of the United Nations. Former United Nations Secretary General Kurt Waldheim felt that this new world order was a projection of the American dream into Europe and that in its naïveté the idea of a new order had been used to further the parochial interests of Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau, thus ensuring the League's eventual failure. Although some have claimed the phrase was not used at all, Virginia Gildersleeve, the sole female delegate to the San Francisco Conference in April 1945, did use it in an interview with The New York Times.

The phrase was used by some in retrospect when assessing the creation of the post-World War II set of international institutions, including the United Nations; the U.S. security alliances such as NATO; the Bretton Woods system of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; and even the Truman Doctrine and Marshall Plan were seen as characterizing or comprising this new order.

H. G. Wells wrote a book published in 1940 entitled The New World Order. It addressed the ideal of a world without war in which law and order emanated from a world governing body and examined various proposals and ideas.

Franklin D. Roosevelt in his "Armistice Day Address Before the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier" on November 11, 1940, referred to Novus ordo seclorum, inscribed on the Great Seal of the United States and traced to antiquity. By this phrase, Virgil announced the Augustan Golden Age. That Age was the dawn of the divine universal monarchy,

but Roosevelt on that occasion promised to take the world order into

the opposite democratic direction led by the United States and Britain.

On June 6, 1966, New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy used the phrase "new world society" in his Day of Affirmation Address in South Africa.

Post-Cold War usage

The phrase "new world order" as used to herald in the post-Cold War

era had no developed or substantive definition. There appear to have

been three distinct periods in which it was progressively redefined,

first by the Soviets and later by the United States before the Malta

Conference and again after George H. W. Bush's speech of September 11, 1990.

- At first, the new world order dealt almost exclusively with nuclear disarmament and security arrangements. Mikhail Gorbachev would then expand the phrase to include United Nations strengthening and great power cooperation on a range of North–South economic, and security problems. Implications for NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and European integration were subsequently included.

- The Malta Conference collected these various expectations and they were fleshed out in more detail by the press. German reunification, human rights and the polarity of the international system were then included.

- The Gulf War crisis refocused the term on superpower

cooperation and regional crises. Economic North–South problems, the

integration of the Soviets into the international system and the changes

in economic and military polarity received greater attention.

Mikhail Gorbachev's formulation

The first press reference to the phrase came from Russo-Indian talks on November 21, 1988. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi used the term in reference to the commitments made by the Soviet Union through the Declaration of Delhi of two years previous. The new world order which he describes is characterized by "non-violence

and the principles of peaceful coexistence". He also includes the

possibility of a sustained peace, an alternative to the nuclear balance of terror, dismantling of nuclear weapons systems, significant cuts in strategic arms and eventually a general and complete disarmament.

Three days later, a Guardian article quotes NATO Secretary General Manfred Wörner

as saying that the Soviets have come close to accepting NATO's doctrine

of military stability based on a mix of nuclear as well as conventional arms. In his opinion, this would spur the creation of "a new security framework" and a move towards "a new world order".

However, the principal statement creating the new world order concept came from Mikhail Gorbachev's

December 7, 1988 speech to the United Nations General Assembly. His

formulation included an extensive list of ideas in creating a new order.

He advocated strengthening the central role of the United Nations and

the active involvement of all members—the Cold War had prevented the

United Nations and its Security Council from performing their roles as

initially envisioned. The de-ideologizing

of relations among states was the mechanism through which this new

level of cooperation could be achieved. Concurrently, Gorbachev

recognized only one world economy—essentially an end to economic blocs. Furthermore, he advocated Soviet entry into several important international organizations, such as the CSCE and International Court of Justice. Reinvigoration of the United Nations peacekeeping

role and recognition that superpower cooperation can and will lead to

the resolution of regional conflicts was especially key in his

conception of cooperation. He argued that the use of force or the threat

of the use of force was no longer legitimate and that the strong must

demonstrate restraint toward the weak. As the major powers of the world,

he foresaw the United States, the Soviet Union, Europe, India, China,

Japan and Brazil. He asked for cooperation on environmental protection, on debt relief for developing countries, on disarmament of nuclear weapons, on preservation of the ABM treaty and on a convention for the elimination of chemical weapons.

At the same time, he promised the significant withdrawal of Soviet

forces from Eastern Europe and Asia as well as an end to the jamming of Radio Liberty.

Gorbachev described a phenomenon that could be described as a global political awakening:

We are witnessing most profound

social change. Whether in the East or the South, the West or the North,

hundreds of millions of people, new nations and states, new public

movements and ideologies have moved to the forefront of history.

Broad-based and frequently turbulent popular movements have given

expression, in a multidimensional and contradictory way, to a longing

for independence, democracy and social justice.

The idea of democratizing the entire world order has become a powerful

socio-political force. At the same time, the scientific and

technological revolution has turned many economic, food, energy,

environmental, information and population problems, which only recently

we treated as national or regional ones, into global problems. Thanks

to the advances in mass media

and means of transportation, the world seems to have become more

visible and tangible. International communication has become easier than

ever before.

In the press, Gorbachev was compared to Woodrow Wilson giving the Fourteen Points, to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill promulgating the Atlantic Charter and to George Marshall and Harry S. Truman building the Western Alliance.

While visionary, his speech was to be approached with caution as he was

seen as attempting a fundamental redefinition of international

relationships, on economic and environmental levels. His support "for

independence, democracy and social justice" was highlighted, but the

principle message taken from his speech was that of a new world order

based on pluralism, tolerance and cooperation.

For a new type of progress throughout the world to become a reality, everyone must change. Tolerance is the alpha and omega of a new world order.

— Gorbachev, June 1990

A month later, Time Magazine

ran a longer analysis of the speech and its possible implications. The

promises of a new world order based on the forswearing of military use

of force was viewed partially as a threat, which might "lure the West

toward complacency" and "woo Western Europe into neutered neutralism". However, the more overriding threat was that the West

did not yet have any imaginative response to Gorbachev—leaving the

Soviets with the moral initiative and solidifying Gorbachev's place as

"the most popular world leader in much of Western Europe".

The article noted as important his de-ideologized stance, willingness

to give up use of force, commitment to troop cuts in Eastern Europe

(accelerating political change there) and compliance with the ABM

treaty. According to the article, the new world order seemed to imply

shifting of resources from military to domestic needs; a world community

of states based on the rule of law;

a dwindling of security alliances like NATO and the Warsaw Pact; and an

inevitable move toward European integration. The author of the Time article felt that George H. W. Bush should counter Gorbachev's "common home"

rhetoric toward the Europeans with the idea of "common ideals", turning

an alliance of necessity into one of shared values. Gorbachev's

repudiation of expansionism leaves the United States in a good position, no longer having to support anti-communist dictators and able to pursue better goals such as the environment; nonproliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons; reducing famine and poverty; and resolving regional conflicts. In A World Transformed, Bush and Brent Scowcroft's

similarly concern about losing leadership to Gorbachev is noted and

they worry that the Europeans might stop following the U.S. if it

appears to drag its feet.

As Europe passed into the new year, the implications of the new world order for the European Community

surfaced. The European Community was seen as the vehicle for

integrating East and West in such a manner that they could "pool their

resources and defend their specific interests in dealings with those

superpowers on something more like equal terms". It would be less

exclusively tied to the U.S. and stretch "from Brest to Brest-Litovsk, or at least from Dublin to Lublin".

By July 1989, newspapers were still criticizing Bush for his lack of

response to Gorbachev's proposals. Bush visited Europe, but "left

undefined for those on both sides of the Iron Curtain

his vision for the new world order", leading commentators to view the

U.S. as over-cautious and reactive, rather than pursuing long-range

strategic goals.

Malta Conference

In A World Transformed, Bush and Scowcroft detail their crafting of a strategy aimed at flooding Gorbachev with proposals at the Malta Conference to catch him off guard, preventing the U.S. from coming out of the summit on the defensive.

The Malta Conference on December 2–3, 1989 reinvigorated

discussion of the new world order. Various new concepts arose in the

press as elements on the new order. Commentators expected the

replacement of containment with superpower cooperation. This cooperation

might then tackle problems such as reducing armaments and troop

deployments, settling regional disputes, stimulating economic growth,

lessening East–West trade restrictions, the inclusion of the Soviets in

international economic institutions and protecting the environment.

Pursuant to superpower cooperation, a new role for NATO was forecast,

with the organization perhaps changing into a forum for negotiation and

treaty verification, or even a wholesale dissolution of NATO and the

Warsaw Pact following the resurrection of the four-power framework from

World War II (i.e. the United States, United Kingdom, France and

Russia). However, continued U.S. military presence in Europe was

expected to help contain "historic antagonisms", thus making possible a new European order.

In Europe, German reunification was seen as part of the new order. However, Strobe Talbott

saw it as more of a brake on the new era and believed Malta to be a

holding action on part of the superpowers designed to forestall the "new

world order" because of the German question.

Political change in Eastern Europe also arose on the agenda. The

Eastern Europeans believed that the new world order did not signify

superpower leadership, but that superpower dominance was coming to an

end.

In general, the new security structure arising from superpower

cooperation seemed to indicate to observers that the new world order

would be based on the principles of political liberty,

self-determination and non-intervention. This would mean an end to the

sponsoring of military conflicts in third countries, restrictions on

global arms sales, and greater engagement in the Middle East (especially regarding Syria, Palestine and Israel). The U.S. might use this opportunity to more emphatically promote human rights in China and South Africa.

Economically, debt relief was expected to be a significant issue

as East–West competition would give way to North–South cooperation.

Economic tripolarity would arise with the U.S., Germany and Japan

as the three motors of world growth. Meanwhile, the Soviet social and

economic crisis was manifestly going to limit its ability to project

power abroad, thus necessitating continued U.S. leadership.

Commentators assessing the results of the Conference and how the

pronouncements measured up to expectations, were underwhelmed. Bush was

criticized for taking refuge behind notions of "status quo-plus"

rather than a full commitment to new world order. Others noted that

Bush thus far failed to satisfy the out-of-control "soaring

expectations" that Gorbachev's speech unleashed.

Gulf War and Bush's formulation

Bush greeting troops on the eve of the First

Gulf WarBush started to take the initiative from Gorbachev during the run-up to the Persian Gulf War,

when he began to define the elements of the new world order as he saw

it and link the new order's success to the international community's

response in Kuwait.

Initial agreement by the Soviets to allow action against Saddam Hussein highlighted this linkage in the press. The Washington Post

declared that this superpower cooperation demonstrates that the Soviet

Union has joined the international community and that in the new world

order Saddam faces not just the U.S., but the international community

itself. A New York Times

editorial was the first to assert that at stake in the collective

response to Saddam was "nothing less than the new world order which Bush

and other leaders struggle to shape".

In A World Transformed, Scowcroft notes that Bush even

offered to have Soviet troops amongst the coalition forces liberating

Kuwait. Bush places the fate of the new world order on the ability of

the U.S. and the Soviet Union to respond to Hussein's aggression.

The idea that the Persian Gulf War would usher in the new world order

began to take shape. Bush notes that the "premise [was] that the United

States henceforth would be obligated to lead the world community to an

unprecedented degree, as demonstrated by the Iraqi crisis, and that we should attempt to pursue our national interests, wherever possible, within a framework of concert with our friends and the international community".

On March 6, 1991, President Bush addressed Congress

in a speech often cited as the Bush administration's principal policy

statement on the new world order in the Middle East following the

expulsion of Iraqi forces from Kuwait. Michael Oren

summarizes the speech, saying: "The president proceeded to outline his

plan for maintaining a permanent U.S. naval presence in the Persian

Gulf, for providing funds for Middle East development, and for

instituting safeguards against the spread of unconventional weapons.

The centerpiece of his program, however, was the achievement of an

Arab-Israeli treaty based on the territory-for-peace principle and the

fulfillment of Palestinian rights". As a first step, Bush announced his

intention to reconvene the international peace conference in Madrid.

A pivotal point came with Bush's September 11, 1990 "Toward a New World Order" speech (full text) to a joint session of Congress. This time it was Bush, not Gorbachev, whose idealism was compared to Woodrow Wilson and to Franklin D. Roosevelt at the creation of the United Nations. Key points picked up in the press were:

- Commitment to U.S. strength, such that it can lead the world

toward rule of law, rather than use of force. The Gulf crisis was seen

as a reminder that the U.S. must continue to lead and that military

strength does matter, but that the resulting new world order should make

military force less important in the future.

- Soviet–American partnership in cooperation toward making the world

safe for democracy, making possible the goals of the United Nations for

the first time since its inception. Some countered that this was

unlikely and that ideological tensions would remain, such that the two

superpowers could be partners of convenience for specific and limited

goals only. The inability of the Soviet Union to project force abroad

was another factor in skepticism toward such a partnership.

- Another caveat raised was that the new world order was based not on

U.S.-Soviet cooperation, but really on Bush-Gorbachev cooperation and

that the personal diplomacy made the entire concept exceedingly fragile.

- Future cleavages were to be economic, not ideological, with the

First and Second World cooperating to contain regional instability in

the Third World. Russia could become an ally against economic assaults from Asia, Islamic terrorism and drugs from Latin America.

- Soviet integration into world economic institutions such as the G7 and establishment of ties with the European Community.

- Restoration of German sovereignty and Cambodia's acceptance of the United Nations Security Council's peace plan on the day previous to the speech were seen as signs of what to expect in the new world order.

- The reemergence of Germany and Japan as members of the great powers

and concomitant reform of the United Nations Security Council was seen

as necessary for great power cooperation and reinvigorated United

Nations leadership

- Europe was seen as taking the lead on building their own world order

while the U.S. was relegated to the sidelines. The rationale for U.S.

presence on the continent was vanishing and the Persian Gulf crisis was

seen as incapable of rallying Europe. Instead, Europe was discussing the

European Community, the CSCE and relations with the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev even proposed an all-European security council to replace the

CSCE, in effect superseding the increasingly irrelevant NATO.

- A very few postulated a bi-polar new order of U.S. power and United Nations moral authority,

the first as global policeman, the second as global judge and jury. The

order would be collectivist in which decisions and responsibility would

be shared.

These were the common themes which emerged from reporting about Bush's speech and its implications.

Critics held that Bush and Baker remained too vague about what exactly the order entailed:

Does it mean a strengthened U.N.?

And new regional security arrangements in the gulf and elsewhere? Will

the U.S. be willing to put its own military under international

leadership? In the Persian Gulf, Mr. Bush has rejected a UN command

outright. Sometimes, when Administration officials describe their goals,

they say the U.S. must reduce its military burden and commitment. Other

times, they appear determined to seek new arrangements to preserve U.S.

military supremacy and to justify new expenditures.

The New York Times observed that the American left was calling the new world order a "rationalization for imperial ambitions" in the Middle East while the right rejected new security arrangements altogether and fulminated about any possibility of United Nations revival. Pat Buchanan

predicted that the Persian Gulf War would in fact be the demise of the

new world order, the concept of United Nations peacekeeping and the

U.S.'s role as global policeman.

The Los Angeles Times

reported that the speech signified more than just the rhetoric about

superpower cooperation. In fact, the deeper reality of the new world

order was the U.S.' emergence "as the single greatest power in a

multipolar world". Moscow was crippled by internal problems and thus

unable to project power abroad. While hampered by economic malaise, the

U.S. was militarily unconstrained for the first time since the end of

World War II. Militarily, it was now a unipolar world as illustrated by

the Persian Gulf crisis. While diplomatic rhetoric stressed a

U.S.-Soviet partnership, the U.S. was deploying troops to Saudi Arabia (a mere 700 miles from the Soviet frontier) and was preparing for war against a former Soviet client state.

Further, U.S. authority over the Soviets was displayed in 1. The

unification of Germany, withdrawal of Soviet forces, and almost open

appeal to Washington for aid in managing the Soviet transition to

democracy; 2. Withdrawal of Soviet support for Third World clients; and

3) Soviets seeking economic aid through membership in Western

international economic and trade communities.

The speech was indeed pivotal but the meaning hidden. A pivotal

interpretation of the speech came the same month a week later on

September 18, 1990. Charles Krauthammer then delivered a lecture in Washington in which he introduced the idea of American unipolarity. By the fall 1990, his essay was published in Foreign Affairs titled "The Unipolar Moment". It had little to do with Kuwait. The main point was the following:

It has been assumed that the old

bipolar world would beget a multipolar world… The immediate post-Cold

War world is not multipolar. It is unipolar. The center of world power

is an unchallenged superpower, the United States, attended by its

Western allies.

In fact, as Lawrence Freedman commented in 1991, a "unipolar" world is now taken seriously. He details:

An underlying theme in all the

discussions is that the United States has now acquired a preeminent

position in the international hierarchy. This situation has developed

because of the precipitate decline of the Soviet Union. Bush himself has

indicated that it is the new relationship with Moscow that creates the

possibility for his new order. For many analysts, therefore, the new

order's essential feature is not the values it is said to embody nor the

principles upon which it is to be based, but that it has the United

States at its center... In effect, the debate is over the consequences

of the West's victory in the Cold War rather than in the Gulf for the

generality of international conflicts.

Washington's capacity to exert overwhelming military power and

leadership over a multinational coalition provides the "basis for a Pax Americana".

Indeed, one of the problems with Bush's phrase was that "a call for

'order' from Washington chills practically everyone else, because it

sounds suspiciously like a Pax Americana". The unipolarity, Krauthammer noted, is the "most striking feature of the post-Cold War world". The article proved to be epochal. Twelve years later, Krauthammer in "The Unipolar Moment Revisited" stated that the "moment" is lasting and lasting with "acceleration".

He replied to those who still refused to acknowledge the fact of

unipolarity: "If today's American primacy does not constitute

unipolarity, then nothing ever will".

In 1990, Krauthammer had estimated that the "moment" will last forty

years at best, but he adjusted the estimation in 2002: "Today, it seems

rather modest. The unipolar moment has become the unipolar era".

On the latter occasion, Krauthammer added perhaps his most significant

comment—the new unipolar world order represents a "unique to modern

history" structure.

Presaging the Iraq War of 2003

The Economist published an article explaining the drive toward the Persian Gulf War in terms presaging the run-up to the Iraq War of 2003. The author notes directly that despite the coalition, in the minds of most governments this is the U.S.' war and George W. Bush

that "chose to stake his political life on defeating Mr Hussein". An

attack on Iraq would certainly shatter Bush's alliance, they assert,

predicting calls from United Nations Security Council members saying

that diplomacy should have been given more time and that they will not

wish to allow a course of action "that leaves America sitting too

prettily as sole remaining superpower". When the unanimity of the

Security Council ends, "all that lovely talk about the new world order"

will too. When casualties mount, "Bush will be called a warmonger, an imperialist and a bully". The article goes on to say that Bush and James Baker's

speechifying cannot save the new world order once they launch a

controversial war. It closes noting that a wide consensus is not

necessary for U.S. action—only a hardcore of supporters, namely Gulf Cooperation Council states (including Saudi Arabia), Egypt and Britain. The rest need only not interfere.

In a passage with similar echoes of the future, Bush and Scowcroft explain in A World Transformed the role of the United Nations Secretary-General in attempting to avert the Persian Gulf War. Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar arrived at Camp David

to ask what he could do to head off the war. Bush told him that it was

important that we get full implementation on every United Nations

resolution: "If we compromise, we weaken the UN and our own credibility

in building this new world order," I said. "I think Saddam Hussein

doesn't believe force will be used—or if it is, he can produce a

stalemate". Additional meetings between Baker or Pérez and the Iraqis

are rejected for fear that they will simply come back empty-handed once

again. Bush feared that Javier will be cover for Hussein's

manipulations. Pérez suggested another Security Council meeting, but

Bush saw no reason for one.

Following the Persian Gulf War

Following

the Persian Gulf War which was seen as the crucible in which great

power cooperation and collective security would emerge the new norms of

the era—several academic assessments of the "new world order" idea were

published.

John Lewis Gaddis, a Cold War historian, wrote in Foreign Affairs

about what he saw as the key characteristics of the potential new

order, namely unchallenged American primacy, increasing integration,

resurgent nationalism

and religiosity, a diffusion of security threats and collective

security. He casts the fundamental challenge as one of integration

versus fragmentation and the concomitant benefits and dangers associated

with each. Changes in communications,

the international economic system, the nature of security threats and

the rapid spread of new ideas would prevent nations from retreating into

isolation. In light of this, Gaddis sees a chance for the democratic peace predicted by liberal international relations theorists

to come closer to reality. However, he illustrates that not only is the

fragmentary pressure of nationalism manifest in the former Communist

bloc countries and the Third World, but it is also a considerable factor in the West. Further, a revitalized Islam

could play both integrating and fragmenting roles—emphasizing common

identity, but also contributing to new conflicts that could resemble the

Lebanese Civil War. The integration coming from the new order could also aggravate ecological, demographic and epidemic threats. National self-determination,

leading to the breakup and reunification of states (such as Yugoslavia

on one hand and Germany on the other) could signal abrupt shifts in the

balance of power with a destabilizing effect. Integrated markets,

especially energy markets, are now a security liability for the world

economic system as events affecting energy security

in one part of the globe could threaten countries far removed from

potential conflicts. Finally, diffusion of security threats required a

new security paradigm involving low-intensity, but more frequent

deployment of peacekeeping troops—a type of mission that is hard to

sustain under budgetary or public opinion pressure. Gaddis called for

aid to Eastern European countries, updated security and economic regimes

for Europe, United Nations-based regional conflict resolution, a slower

pace of international economic integration and paying off the U.S. debt.

However, statesman Strobe Talbott

wrote of the new world order that it was only in the aftermath of the

Persian Gulf War that the United Nations took a step toward redefining

its role to take account of both interstate relations and intrastate

events. Furthermore, he asserted that it was only as an unintended

postscript to Desert Storm that Bush gave meaning to the "new world

order" slogan. By the end of the year, Bush stopped talking about a new

world order and his advisers explained that he had dropped the phrase

because he felt it suggested more enthusiasm for the changes sweeping

the planet than he actually felt. As an antidote to the uncertainties of

the world, he wanted to stress the old verities of territorial

integrity, national sovereignty and international stability. David Gergen suggested at the time that it was the recession of 1991–1992 which finally killed the new world order idea within the White House.

The economic downturn took a deeper psychological toll than expected

while domestic politics were increasingly frustrated by paralysis, with

the result that the United States toward the end of 1991 turned

increasingly pessimistic, inward and nationalistic.

In 1992, Hans Köchler

published a critical assessment of the notion of the "new world order",

describing it as an ideological tool of legitimation of the global

exercise of power by the U.S. in a unipolar environment. In Joseph Nye's analysis (1992), the collapse of the Soviet Union

did not issue in a new world order per se, but rather simply allowed

for the reappearance of the liberal institutional order that was

supposed to have come into effect in 1945. However, this success of this

order was not a fait accomplis. Three years later, John Ikenberry

would reaffirm Nye's idea of a reclamation of the ideal post-World War

II order, but would dispute the nay-sayers who had predicted post-Cold

War chaos. By 1997, Anne-Marie Slaughter

produced an analysis calling the restoration of the post-World War II

order a "chimera ... infeasible at best and dangerous at worst". In her

view, the new order was not a liberal institutionalist one, but one in

which state authority disaggregated and decentralized in the face of globalization.

Samuel Huntington wrote critically of the "new world order" and of Francis Fukuyama's End of History theory in The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order:

- The expectation of harmony was widely shared. Political and

intellectual leaders elaborated similar views. The Berlin wall had come

down, communist regimes had collapsed, the United Nations was to assume a

new importance, the former Cold War rivals would engage in

"partnership" and a "grand bargain," peacekeeping and peacemaking would

be the order of the day. The President of the world's leading country

proclaimed the "new world order"...

- The moment of euphoria at the end of the Cold War generated an

illusion of harmony, which was soon revealed to be exactly that. The

world became different in the early 1990s, but not necessarily more

peaceful. Change was inevitable; progress was not... The illusion of

harmony at the end of that Cold War was soon dissipated by the

multiplication of ethnic conflicts and "ethnic cleansing," the breakdown of law and order, the emergence of new patterns of alliance and conflict among states, the resurgence of neo-communist and neo-fascist movements, intensification of religious fundamentalism, the end of the "diplomacy of smiles" and "policy of yes"

in Russia's relations with the West, the inability of the United

Nations and the United States to suppress bloody local conflicts, and

the increasing assertiveness of a rising China. In the five years after

the Berlin wall came down, the word "genocide" was heard far more often than in any five years of the Cold War.

- The one harmonious world paradigm is clearly far too divorced from

reality to be a useful guide to the post–Cold War world. Two Worlds: Us

and Them. While one-world expectations appear at the end of major

conflicts, the tendency to think in terms of two worlds recurs

throughout human history. People are always tempted to divide people

into us and them, the in-group and the other, our civilization and those

barbarians.

Despite the criticisms of the new world order concept, ranging from its practical unworkability to its theoretical incoherence, Bill Clinton

not only signed on to the idea of the "new world order", but

dramatically expanded the concept beyond Bush's formulation. The essence

of Clinton's election year critique was that Bush had done too little, not too much.

American intellectual Noam Chomsky, author of the 1994 book World Orders Old and New, often describes the "new world order" as a post-Cold-War era in which "the New World gives the orders". Commenting on the 1999 U.S.-NATO bombing of Serbia, he writes:

The aim of these assaults is to

establish the role of the major imperialist powers—above all, the United

States—as the unchallengeable arbiters of world affairs. The "New World

Order" is precisely this: an international regime of unrelenting

pressure and intimidation by the most powerful capitalist states against

the weakest.

Following the rise of Boris Yeltsin eclipsing Gorbachev and the election victory

of Clinton over Bush, the term "new world order" fell from common

usage. It was replaced by competing similar concepts about how the

post-Cold War order would develop. Prominent among these were the ideas

of the "era of globalization", the "unipolar moment", the "end of history" and the "Clash of Civilizations".

Viewed in retrospect

A 2001 paper in Presidential Studies Quarterly

examined the idea of the "new world order" as it was presented by the

Bush administration (mostly ignoring previous uses by Gorbachev). Their

conclusion was that Bush really only ever had three firm aspects to the

new world order:

- Checking the offensive use of force.

- Promoting collective security.

- Using great power cooperation.

These were not developed into a policy architecture, but came about

incrementally as a function of domestic, personal and global factors.

Because of the somewhat overblown expectations for the new world order

in the media, Bush was widely criticized for lacking vision.

The Gulf crisis is seen as the catalyst for Bush's development

and implementation of the new world order concept. The authors note that

before the crisis the concept remained "ambiguous, nascent, and

unproven" and that the U.S had not assumed a leadership role with

respect to the new order. Essentially, the Cold War's end was the

permissive cause for the new world order, but the Persian Gulf crisis

was the active cause.

They reveal that in August 1990 U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia Charles W. Freeman Jr.

sent a diplomatic cable to Washington from Saudi Arabia in which he

argued that U.S. conduct in the Persian Gulf crisis would determine the

nature of the world. Bush would then refer to the "new world order" at

least 42 times from the summer of 1990 to the end of March 1991. They

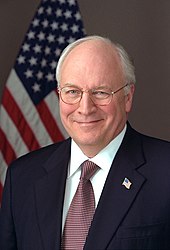

also note that Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney gave three priorities to the Senate

on fighting the Persian Gulf War, namely prevent further aggression,

protect oil supplies and further a new world order. The authors note

that the new world order did not emerge in policy speeches until after

Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, maintaining that the concept was clearly not

critical in the U.S. decision to deploy. John H. Sununu

later indicated that the administration wanted to refrain from talking

about the concept until Soviet collapse was more clear. A reversal of

Soviet collapse would have been the death knell for the new order.

Bush and Scowcroft were frustrated by the exaggerated and

distorted ideas surrounding the new world order. They did not intend to

suggest that the U.S. would yield significant influence to the United

Nations, or that they expected the world to enter an era of peace and

tranquility. They preferred multilateralism, but did not reject unilateralism. The new world order did not signal peace, but a "challenge to keep the dangers of disorder at bay".

Bush's drive toward the Persian Gulf War was based on the world

making a clear choice. Baker recalls that UNSCR 660's "language was

simply and crystal clear, purposely designed by us to frame the vote as

being for or against aggression". Bush's motivation centered around 1.

The dangers of appeasement;

and 2. Failure to check aggression could spark further aggression. Bush

repeatedly invoked images of World War II in this connection and became

very emotional over Iraqi atrocities being committed in Kuwait.

He also believed that failure to check Iraqi aggression would lead to

more challenges to the U.S.-favored status quo and global stability.

While the end of the Cold War increased U.S. security globally, it

remained vulnerable to regional threats. Furthermore, Washington

believed that addressing the Iraqi threat would help reassert U.S.

predominance in light of growing concerns about relative decline,

following the resurgence of Germany and Japan.

The Gulf War was also framed as a test case for United Nations

credibility. As a model for dealing with aggressors, Scowcroft believed

that the United States ought to act in a way that others can trust and

thus get United Nations support. It was critical that the U.S. not look

like it was throwing its weight around. Great power cooperation and

United Nations support would collapse if the U.S. marched on the Baghdad

to try to remake Iraq. However, practically, superpower cooperation was

limited. For example, when the U.S. deployed troops to Saudi Arabia,

Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze became furious at not being consulted.

By 1992, the authors note that the U.S. was already abandoning the idea of collective action. The leaked draft of the Wolfowitz-Libby

1992 Defense Guidance Report effectively confirmed this shift as it

called for a unilateral role for the U.S. in world affairs, focusing on

preserving American dominance.

In closing A World Transformed, Scowcroft sums up what his

expectations were for the new world order. He states that the U.S. has

the strength and the resources to pursue its own interests, but has a

disproportionate responsibility to use its power in pursuit of the

common good as well as an obligation to lead and to be involved. The

U.S. is perceived as uncomfortable in exercising its power and ought to

work to create predictability and stability in international relations.

The U.S. needs not be embroiled in every conflict, but ought to aid in

developing multilateral responses to them. The U.S. can unilaterally

broker disputes, but ought to act whenever possible in concert with

equally committed partners to deter major aggression.

Recent political usage

Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

stated in 1994: "The New World Order cannot happen without U.S.

participation, as we are the most significant single component. Yes,

there will be a New World Order, and it will force the United States to

change its perceptions". Then on January 5, 2009, when asked on television by CNBC anchors about what he suggests U.S. President Barack Obama

focus on during the current Israeli crises he replied that it is a time

to reevaluate American foreign policy and that "he can give new impetus

to American foreign policy. ... I think that his task will be to

develop an overall strategy for America in this period, when really a

'new world order' can be created. It's a great opportunity. It isn't

such a crisis".

Former United Kingdom Prime Minister and British Middle East envoy Tony Blair stated on November 13, 2000, in his Mansion House speech: "There is a new world order like it or not". He used the term in 2001, November 12, 2001 and 2002.

On January 7, 2003, he stated that "the call was for a new world order.

But a new order presumes a new consensus. It presumes a shared agenda

and a global partnership to do it".

Former United Kingdom Prime Minister Gordon Brown (then Chancellor of the Exchequer)

stated on December 17, 2001: "This is not the first time the world has

faced this question – so fundamental and far-reaching. In the 1940s,

after the greatest of wars, visionaries in America and elsewhere looked

ahead to a new world and – in their day and for their times – built a

new world order".

Brown also called for a "new world order" in a 2008 speech in New Delhi to reflect the rise of Asia and growing concerns over global warming and finance.

Brown said the new world order should incorporate a better

representation of "the biggest shift in the balance of economic power in

the world in two centuries". He went on to say: "To succeed now, the

post-war rules of the game and the post-war international institutions –

fit for the Cold War and a world of just 50 states – must be radically

reformed to fit our world of globalisation". He also called for the revamping of post-war global institutions including the World Bank, G8 and International Monetary Fund. Other elements of Brown's formulation include spending £100 million a year on setting up a rapid reaction force to intervene in failed states.

He also used the term on January 14, 2007, March 12, 2007, May 15, 2007, June 20, 2007, April 15, 2008 and on April 18, 2008. Brown also used the term in his speech at the G20 Summit in London on April 2, 2009.

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

has called for a "new world order" based on new ideas, saying the era

of tyranny has come to a dead-end. In an exclusive interview with Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), Ahmadinejad noted that it is time to propose new ideologies for running the world.

Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili

said "it's time to move from words to action because this is not going

to go away. This nation is fighting for its survival, but we are also

fighting for world peace and we are also fighting for a Future World

Order".

Turkish President Abdullah Gül

said: "I don't think you can control all the world from one centre,

There are big nations. There are huge populations. There is unbelievable

economic development in some parts of the world. So what we have to do

is, instead of unilateral actions, act all together, make common

decisions and have consultations with the world. A new world order, if I

can say it, should emerge".

On the Colbert Report, guest John King (of CNN) mentioned Obama's "New World Order" after Stephen Colbert joked about the media's role in getting Obama elected.

Some scholars of international relations have advanced the thesis

that the declining global influence of the U.S. and the rise of largely

illiberal powers such as China threaten the established norms and

beliefs of the liberal rule-based world order. They describe three

pillars of the prevailing order that are upheld and promoted by the

West, namely peaceful international relations (the Westphalian norm),

democratic ideals and free-market capitalism. Stewart Patrick suggests

that emerging powers, China included, "often oppose the political and

economic ground rules of the inherited Western liberal order" and Elizabeth Economy argues that China is becoming a "revolutionary power" that is seeking "to remake global norms and institutions".

Russian political analyst Leonid Grinin believes that despite all

the problems, the U.S. will preserve the leading position within a new

world order since no other country is able to concentrate so many

leader's functions. Yet, he insists that the formation of a new world

order will start from an epoch of new coalitions.

Xi Jinping, China's paramount leader, has called for a new world order, in his speech to the Boao Forum

for Asia, in April 2021. He criticized US global leadership and its

interference on other countries' internal affairs. "The rules set by one

or several countries should not be imposed on others, and the

unilateralism of individual countries should not give the whole world a

rhythm" he said.

U.S. President Joe Biden

said during a gathering of business leaders at the White House in March

2022 that the recent changes in global affairs caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine

provided an opportunity for a new world order with U.S. leadership,

stating that this project would have to be carried out in partnership

with "the rest of the free world."

According to Tony Blair's the annual Ditchley lecture in Jul 2022

, China, not Russia, will bring about the largest geopolitical change

of this century. The era of western political and economic domination is

coming to an end. The future of the world will be at the very least

bipolar and possibly multipolar. The east and west can now coexist on

equal level for the first time in contemporary history.

The role of soft power must not be overlooked by the west,

according to Blair, as China and other nations like Russia, Turkey, and

Iran invest money in the developing world while forging close political

and military ties.