From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tissue_(biology)

In biology, tissue is a biological organizational level between cells and a complete organ. A tissue is an ensemble of similar cells and their extracellular matrix from the same origin that together carry out a specific function. Organs are then formed by the functional grouping together of multiple tissues.

The English word "tissue" derives from the French word "tissu", the past participle of the verb tisser, "to weave".

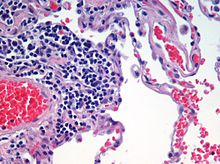

The study of tissues is known as histology or, in connection with disease, as histopathology. Xavier Bichat is considered as the "Father of Histology". Plant histology is studied in both plant anatomy and physiology. The classical tools for studying tissues are the paraffin block in which tissue is embedded and then sectioned, the histological stain, and the optical microscope. Developments in electron microscopy, immunofluorescence, and the use of frozen tissue-sections have enhanced the detail that can be observed in tissues. With these tools, the classical appearances of tissues can be examined in health and disease, enabling considerable refinement of medical diagnosis and prognosis.

Plant tissue

In plant anatomy, tissues are categorized broadly into three tissue systems: the epidermis, the ground tissue, and the vascular tissue.

- Epidermis – Cells forming the outer surface of the leaves and of the young plant body.

- Vascular tissue – The primary components of vascular tissue are the xylem and phloem. These transport fluids and nutrients internally.

- Ground tissue – Ground tissue is less differentiated than other tissues. Ground tissue manufactures nutrients by photosynthesis and stores reserve nutrients.

Plant tissues can also be divided differently into two types:

- Meristematic tissues

- Permanent tissues.

Meristematic tissue

Meristematic tissue consists of actively dividing cells and leads to increase in length and thickness of the plant. The primary growth of a plant occurs only in certain specific regions, such as in the tips of stems or roots. It is in these regions that meristematic tissue is present. Cells of this type of tissue are roughly spherical or polyhedral to rectangular in shape, with thin cell walls. New cells produced by meristem are initially those of meristem itself, but as the new cells grow and mature, their characteristics slowly change and they become differentiated as components of meristematic tissue, being classified as:

- Apical meristem : Present at the growing tips of stems and roots, they increase the length of the stem and root. They form growing parts at the apices of roots and stems and are responsible for the increase in length, also called primary growth. This meristem is responsible for the linear growth of an organ.

- Lateral meristem: Cells which mainly divide in one plane and cause the organ to increase in diameter and girth. Lateral meristem usually occurs beneath the bark of the tree as cork cambium and in vascular bundles of dicotyledons as vascular cambium. The activity of this cambium forms secondary growth.

- Intercalary meristem: Located between permanent tissues, it is usually present at the base of the node, internode, and on leaf base. They are responsible for growth in length of the plant and increasing the size of the internode. They result in branch formation and growth.

The cells of meristematic tissue are similar in structure and have a thin and elastic primary cell wall made of cellulose. They are compactly arranged without inter-cellular spaces between them. Each cell contains a dense cytoplasm and a prominent cell nucleus. The dense protoplasm of meristematic cells contains very few vacuoles. Normally the meristematic cells are oval, polygonal, or rectangular in shape.

Meristematic tissue cells have a large nucleus with small or no vacuoles because they have no need to store anything, as opposed to their function of multiplying and increasing the girth and length of the plant, with no intercellular spaces.

Permanent tissues

Permanent tissues may be defined as a group of living or dead cells formed by meristematic tissue and have lost their ability to divide and have permanently placed at fixed positions in the plant body. Meristematic tissues that take up a specific role lose the ability to divide. This process of taking up a permanent shape, size and a function is called cellular differentiation. Cells of meristematic tissue differentiate to form different types of permanent tissues. There are 2 types of permanent tissues:

- simple permanent tissues

- complex permanent tissues

Simple permanent tissue

Simple permanent tissue is a group of cells which are similar in origin, structure, and function . They are of three types:

Parenchyma

Parenchyma (Greek, para – 'beside'; enchyma– infusion – 'tissue') is the bulk of a substance. In plants, it consists of relatively unspecialized living cells with thin cell walls that are usually loosely packed so that intercellular spaces are found between cells of this tissue. These are generally isodiametric, in shape. They contain small number of vacuoles or sometimes they even may not contain any vacuole. Even if they do so the vacuole is of much smaller size than of normal animal cells. This tissue provides support to plants and also stores food. Chlorenchyma is a special type of parenchyma that contains chlorophyll and performs photosynthesis. In aquatic plants, aerenchyma tissues, or large air cavities, give support to float on water by making them buoyant. Parenchyma cells called idioblasts have metabolic waste. Spindle shape fiber also contained into this cell to support them and known as prosenchyma, succulent parenchyma also noted. In xerophytes, parenchyma tissues store water.

Collenchyma

Collenchyma (Greek, ‘Colla’ means gum and ‘enchyma’ means infusion) is a living tissue of primary body like Parenchyma. Cells are thin-walled but possess thickening of cellulose, water and pectin substances (pectocellulose) at the corners where a number of cells join. This tissue gives tensile strength to the plant and the cells are compactly arranged and have very little inter-cellular spaces. It occurs chiefly in hypodermis of stems and leaves. It is absent in monocots and in roots.

Collenchymatous tissue acts as a supporting tissue in stems of young plants. It provides mechanical support, elasticity, and tensile strength to the plant body. It helps in manufacturing sugar and storing it as starch. It is present in the margin of leaves and resists tearing effect of the wind.

Sclerenchyma

Sclerenchyma (Greek, Sclerous means hard and enchyma means infusion) consists of thick-walled, dead cells and protoplasm is negligible. These cells have hard and extremely thick secondary walls due to uniform distribution and high secretion of lignin and have a function of providing mechanical support. They do not have inter-molecular space between them. Lignin deposition is so thick that the cell walls become strong, rigid and impermeable to water which is also known as a stone cell or sclereids. These tissues are mainly of two types: sclerenchyma fiber and sclereids. Sclerenchyma fibre cells have a narrow lumen and are long, narrow and unicellular. Fibers are elongated cells that are strong and flexible, often used in ropes. Sclereids have extremely thick cell walls and are brittle, and are found in nutshells and legumes.

Epidermis

The entire surface of the plant consists of a single layer of cells called epidermis or surface tissue. The entire surface of the plant has this outer layer of the epidermis. Hence it is also called surface tissue. Most of the epidermal cells are relatively flat. The outer and lateral walls of the cell are often thicker than the inner walls. The cells form a continuous sheet without intercellular spaces. It protects all parts of the plant. The outer epidermis is coated with a waxy thick layer called cutin which prevents loss of water. The epidermis also consists of stomata (singular:stoma) which helps in transpiration.

Complex permanent tissue

The complex permanent tissue consists of more than one type of cells having a common origin which work together as a unit. Complex tissues are mainly concerned with the transportation of mineral nutrients, organic solutes (food materials), and water. That's why it is also known as conducting and vascular tissue. The common types of complex permanent tissue are:

Xylem and phloem together form vascular bundles.

Xylem

Xylem (Greek, xylos = wood) serves as a chief conducting tissue of vascular plants. It is responsible for the conduction of water and inorganic solutes. Xylem consists of four kinds of cells:

Xylem tissue is organised in a tube-like fashion along the main axes of stems and roots. It consists of a combination of parenchyma cells, fibers, vessels, tracheids, and ray cells. Longer tubes made up of individual cellssels tracheids, while vessel members are open at each end. Internally, there may be bars of wall material extending across the open space. These cells are joined end to end to form long tubes. Vessel members and tracheids are dead at maturity. Tracheids have thick secondary cell walls and are tapered at the ends. They do not have end openings such as the vessels. The end overlap with each other, with pairs of pits present. The pit pairs allow water to pass from cell to cell.

Though most conduction in xylem tissue is vertical, lateral conduction along the diameter of a stem is facilitated via rays. Rays are horizontal rows of long-living parenchyma cells that arise out of the vascular cambium.

Phloem

Phloem consists of:

- Sieve tube

- Companion cell

- Phloem fibre

- Phloem parenchyma.

Phloem is an equally important plant tissue as it also is part of the 'plumbing system' of a plant. Primarily, phloem carries dissolved food substances throughout the plant. This conduction system is composed of sieve-tube member and companion cells, that are without secondary walls. The parent cells of the vascular cambium produce both xylem and phloem. This usually also includes fibers, parenchyma and ray cells. Sieve tubes are formed from sieve-tube members laid end to end. The end walls, unlike vessel members in xylem, do not have openings. The end walls, however, are full of small pores where cytoplasm extends from cell to cell. These porous connections are called sieve plates. In spite of the fact that their cytoplasm is actively involved in the conduction of food materials, sieve-tube members do not have nuclei at maturity. It is the companion cells that are nestled between sieve-tube members that function in some manner bringing about the conduction of food. Sieve-tube members that are alive contain a polymer called callose, a carbohydrate polymer, forming the callus pad/callus, the colourless substance that covers the sieve plate. Callose stays in solution as long as the cell contents are under pressure. Phloem transports food and materials in plants upwards and downwards as required.

Animal tissue

Animal tissues are grouped into four basic types: connective, muscle, nervous, and epithelial. Collections of tissues joined in units to serve a common function compose organs. While most animals can generally be considered to contain the four tissue types, the manifestation of these tissues can differ depending on the type of organism. For example, the origin of the cells comprising a particular tissue type may differ developmentally for different classifications of animals. Tissue appeared for the first time in the diploblasts, but modern forms only appeared in triploblasts.

The epithelium in all animals is derived from the ectoderm and endoderm (or their precursor in sponges), with a small contribution from the mesoderm, forming the endothelium, a specialized type of epithelium that composes the vasculature. By contrast, a true epithelial tissue is present only in a single layer of cells held together via occluding junctions called tight junctions, to create a selectively permeable barrier. This tissue covers all organismal surfaces that come in contact with the external environment such as the skin, the airways, and the digestive tract. It serves functions of protection, secretion, and absorption, and is separated from other tissues below by a basal lamina.

The connective tissue and the muscular are derived from the mesoderm. The neural tissue is derived from the ectoderm.

Epithelial tissue

The epithelial tissues are formed by cells that cover the organ surfaces, such as the surface of skin, the airways, surfaces of soft organs, the reproductive tract, and the inner lining of the digestive tract. The cells comprising an epithelial layer are linked via semi-permeable, tight junctions; hence, this tissue provides a barrier between the external environment and the organ it covers. In addition to this protective function, epithelial tissue may also be specialized to function in secretion, excretion and absorption. Epithelial tissue helps to protect organs from microorganisms, injury, and fluid loss.

Functions of epithelial tissue:

- The principle function of epithelial tissues are covering and lining of free surface

- The cells of the body's surface form the outer layer of skin.

- Inside the body, epithelial cells form the lining of the mouth and alimentary canal and protect these organs.

- Epithelial tissues help in the elimination of waste.

- Epithelial tissues secrete enzymes and/or hormones in the form of glands.

- Some epithelial tissue perform secretory functions. They secrete a variety of substances including sweat, saliva, mucus, enzymes.

There are many kinds of epithelium, and nomenclature is somewhat variable. Most classification schemes combine a description of the cell-shape in the upper layer of the epithelium with a word denoting the number of layers: either simple (one layer of cells) or stratified (multiple layers of cells). However, other cellular features such as cilia may also be described in the classification system. Some common kinds of epithelium are listed below:

- Simple squamous (pavement) epithelium

- Simple cuboidal epithelium

- Simple Columnar epithelium

- Simple ciliated (pseudostratified) columnar epithelium

- Simple glandular columnar epithelium

- Stratified non-keratinized squamous epithelium

- Stratified keratinized epithelium

- Stratified transitional epithelium

Connective tissue

Connective tissues are fibrous tissues made up of cells separated by non-living material, which is called an extracellular matrix. This matrix can be liquid or rigid. For example, blood contains plasma as its matrix and bone's matrix is rigid. Connective tissue gives shape to organs and holds them in place. Blood, bone, tendon, ligament, adipose, and areolar tissues are examples of connective tissues. One method of classifying connective tissues is to divide them into three types: fibrous connective tissue, skeletal connective tissue, and fluid connective tissue.

Muscular tissue

Muscle cells form the active contractile tissue of the body known as muscle tissue or muscular tissue. Muscle tissue functions to produce force and cause motion, either locomotion or movement within internal organs. Muscle tissue is separated into three distinct categories: visceral or smooth muscle, found in the inner linings of organs; skeletal muscle, typically attached to bones, which generate gross movement; and cardiac muscle, found in the heart, where it contracts to pump blood throughout an organism.

Nervous tissue

Cells comprising the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system are classified as nervous (or neural) tissue. In the central nervous system, neural tissues form the brain and spinal cord. In the peripheral nervous system, neural tissues form the cranial nerves and spinal nerves, inclusive of the motor neurons.

Mineralized tissues

Mineralized tissues are biological tissues that incorporate minerals into soft matrices. Such tissues may be found in both plants and animals,

History

Xavier Bichat introduced word tissue into the study of anatomy by 1801. He was "the first to propose that tissue is a central element in human anatomy, and he considered organs as collections of often disparate tissues, rather than as entities in themselves". Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues from which the organs of the human body are composed, a number later reduced by other authors.