From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trade_union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", such as attaining better wages and benefits (such as holiday, health care, and retirement), improving working conditions, improving safety standards, establishing complaint procedures, developing rules governing status of employees (rules governing promotions, just-cause conditions for termination) and protecting the integrity of their trade through the increased bargaining power wielded by solidarity among workers.

Trade unions typically fund their head office and legal team functions through regularly imposed fees called union dues. The delegate staff of the trade union representation in the workforce are usually made up of workplace volunteers who are often appointed by members in democratic elections.

The trade union, through an elected leadership and bargaining committee, bargains with the employer on behalf of its members, known as the rank-and-file, and negotiates labour contracts (collective bargaining agreements) with employers.

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled or unskilled workers (craft unionism), a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism), or an attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism). The agreements negotiated by a union are binding on the rank-and-file members and the employer, and in some cases on other non-member workers. Trade unions traditionally have a constitution which details the governance of their bargaining unit and also have governance at various levels of government depending on the industry that binds them legally to their negotiations and functioning.

Originating in Great Britain, trade unions became popular in many countries during the Industrial Revolution. Trade unions may be composed of individual workers, professionals, past workers, students, apprentices or the unemployed. Trade union density, or the percentage of workers belonging to a trade union, is highest in the Nordic countries.

Definition

Since the publication of the History of Trade Unionism (1894) by Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the predominant historical view is that a trade union "is a continuous association on wage earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment." Karl Marx described trade unions thus: "The value of labour -power constitutes the conscious and explicit foundation of the trade unions, whose importance for the ... working class can scarcely be overestimated. The trade unions aim at nothing less than to prevent the reduction of wages below the level that is traditionally maintained in the various branches of industry. That is to say, they wish to prevent the price of labour -power from falling below its value" (Capital V1, 1867, p. 1069). Early socialists and Marxists also saw trade unions as a way to democratise the workplace. Through this democratisation, they argued, the capture of political power would be possible.

A modern definition by the Australian Bureau of Statistics states that a trade union is "an organization consisting predominantly of employees, the principal activities of which include the negotiation of rates of pay and conditions of employment for its members."

Yet historian R. A. Lesson, in United we Stand (1971), said:

Two conflicting views of the trade-union movement strove for ascendancy in the nineteenth century: one the defensive-restrictive guild-craft tradition passed down through journeymen's clubs and friendly societies, ... the other the aggressive-expansionist drive to unite all 'labouring men and women' for a 'different order of things'.

Recent historical research by Bob James in Craft, Trade or Mystery (2001) puts forward the view that trade unions are part of a broader movement of benefit societies, which includes medieval guilds, Freemasons, Oddfellows, friendly societies, and other fraternal organizations.

The 18th-century economist Adam Smith noted the imbalance in the rights of workers in regards to owners (or "masters"). In The Wealth of Nations, Book I, chapter 8, Smith wrote:

We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combination of masters, though frequently of those of workmen. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject. Masters are always and everywhere in a sort of tacit, but constant and uniform combination, not to raise the wages of labor above their actual rate[.] When workers combine, masters ... never cease to call aloud for the assistance of the civil magistrate, and the rigorous execution of those laws which have been enacted with so much severity against the combination of servants, labourers and journeymen.

As Smith noted, unions were illegal for many years in most countries, although Smith argued that it should remain illegal to fix wages or prices by employees or employers. There were severe penalties for attempting to organize unions, up to and including execution. Despite this, unions were formed and began to acquire political power, eventually resulting in a body of labour law that not only legalized organizing efforts, but codified the relationship between employers and those employees organized into unions.

History

Trade Guilds

Following the unification of the city-states in Assyria and Sumer by Sargon of Akkad into a single empire ruled from his home city circa 2334 BC, common Mesopotamian standards for length, area, volume, weight, and time used by artisan guilds in each city was promulgated by Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2254–2218 BC), Sargon's grandson, including for shekels. Codex Hammurabi Law 234 (c. 1755–1750 BC) stipulated a 2-shekel prevailing wage for each 60-gur (300-bushel) vessel constructed in an employment contract between a shipbuilder and a ship-owner. Law 275 stipulated a ferry rate of 3-gerah per day on a charterparty between a ship charterer and a shipmaster. Law 276 stipulated a 21⁄2-gerah per day freight rate on a contract of affreightment between a charterer and shipmaster, while Law 277 stipulated a 1⁄6-shekel per day freight rate for a 60-gur vessel. In 1816, an archeological excavation in Minya, Egypt (under an Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire) produced a Nerva–Antonine dynasty-era tablet from the ruins of the Temple of Antinous in Antinoöpolis, Aegyptus that prescribed the rules and membership dues of a burial society collegium established in Lanuvium, Italia in approximately 133 AD during the reign of Hadrian (117–138) of the Roman Empire.

A collegium was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the Lex Julia during the reign of Julius Caesar as Consul and Dictator of the Roman Republic (49–44 BC), and their reaffirmation during the reign of Caesar Augustus as Princeps senatus and Imperator of the Roman Army (27 BC–14 AD), collegia required the approval of the Roman Senate or the Emperor in order to be authorized as legal bodies. Ruins at Lambaesis date the formation of burial societies among Roman Army soldiers and Roman Navy mariners to the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211) in 198 AD. In September 2011, archeological investigations done at the site of the artificial harbor Portus in Rome revealed inscriptions in a shipyard constructed during the reign of Trajan (98–117) indicating the existence of a shipbuilders guild. Rome's La Ostia port was home to a guildhall for a corpus naviculariorum, a collegium of merchant mariners. Collegium also included fraternities of Roman priests overseeing ritual sacrifices, practicing augury, keeping scriptures, arranging festivals, and maintaining specific religious cults.

Modern trade unions

While a commonly held mistaken view holds modern trade unionism to be a product of Marxism, the earliest modern trade unions predate Marx's Communist Manifesto (1848) by almost a century, with the first recorded labour strike in the United States by the Philadelphia printers in 1786. The origins of modern trade unions can be traced back to 18th-century Britain, where the rapid expansion of industrial society then taking place drew masses of people, including women, children, peasants and immigrants into cities. Britain had ended the practice of serfdom in 1574, but vast majority of people remained as tenant-farmers on estates owned by landed aristocracy. This transition was not merely one of relocation from rural to urban environs; rather, the nature of industrial work created a new class of "worker". A farmer worked the land, raised animals and grew crop, and either owned the land or paid rent, but ultimately sold a product and had control over his life and work. As industrial workers, however, the workers sold their work as labour and took directions from employers, giving up part of their freedom and self-agency in the service of a master. The critics of the new arrangement would call this "wage slavery", but the term that persisted was a new form of human relations: employment. Unlike farmers, workers often had less control over their jobs; without job security or a promise of an on-going relationship with their employers, they lacked some control over the work they performed or how it impacted their health and life. It is in this context, then, that modern trade unions emerge.

In the cities, trade unions encountered a large hostility in their early existence from employers and government groups; at the time, unions and unionists were regularly prosecuted under various restraint of trade and conspiracy statutes. This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labour spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout its beginnings, and would later be an important arena for the development of trade unions. Trade unions have sometimes been seen as successors to the guilds of medieval Europe, though the relationship between the two is disputed, as the masters of the guilds employed workers (apprentices and journeymen) who were not allowed to organize.

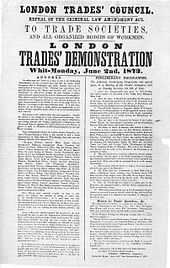

Trade unions and collective bargaining were outlawed from no later than the middle of the 14th century, when the Ordinance of Labourers was enacted in the Kingdom of England, but their way of thinking was the one that endured down the centuries, inspiring evolutions and advances in thinking which eventually gave workers more power. As collective bargaining and early worker unions grew with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the government began to clamp down on what it saw as the danger of popular unrest at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, the Combination Act was passed, which banned trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. Although the unions were subject to often severe repression until 1824, they were already widespread in cities such as London. Workplace militancy had also manifested itself as Luddism and had been prominent in struggles such as the 1820 Rising in Scotland, in which 60,000 workers went on a general strike, which was soon crushed. Sympathy for the plight of the workers brought repeal of the acts in 1824, although the Combination Act 1825 severely restricted their activity.

By the 1810s, the first labour organizations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. The latter name was to hide the organization's real purpose in a time when trade unions were still illegal.

National general unions

The first attempts at setting up a national general union were made in the 1820s and 30s. The National Association for the Protection of Labour was established in 1830 by John Doherty, after an apparently unsuccessful attempt to create a similar national presence with the National Union of Cotton-spinners. The Association quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions, consisting mostly of textile related unions, but also including mechanics, blacksmiths, and various others. Membership rose to between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals spread across the five counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire within a year. To establish awareness and legitimacy, the union started the weekly Voice of the People publication, having the declared intention "to unite the productive classes of the community in one common bond of union."

In 1834, the Welsh socialist Robert Owen established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union. The organization attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries and played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs' case, but soon collapsed.

More permanent trade unions were established from the 1850s, better resourced but often less radical. The London Trades Council was founded in 1860, and the Sheffield Outrages spurred the establishment of the Trades Union Congress in 1868, the first long-lived national trade union center. By this time, the existence and the demands of the trade unions were becoming accepted by liberal middle-class opinion. In Principles of Political Economy (1871) John Stuart Mill wrote:

If it were possible for the working classes, by combining among themselves, to raise or keep up the general rate of wages, it needs hardly be said that this would be a thing not to be punished, but to be welcomed and rejoiced at. Unfortunately the effect is quite beyond attainment by such means. The multitudes who compose the working class are too numerous and too widely scattered to combine at all, much more to combine effectually. If they could do so, they might doubtless succeed in diminishing the hours of labour, and obtaining the same wages for less work. They would also have a limited power of obtaining, by combination, an increase of general wages at the expense of profits.

Beyond this claim Mill also argued that, because individual workers have no basis for assessing the wages for a particular task, labor unions would lead to greater efficiency of the market system.

Legalization, expansion and recognition

British trade unions were finally legalized in 1872, after a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867 agreed that the establishment of the organizations was to the advantage of both employers and employees.

This period also saw the growth of trade unions in other industrializing countries, especially the United States, Germany and France.

In the United States, the first effective nationwide labour organization was the Knights of Labor, in 1869, which began to grow after 1880. Legalization occurred slowly as a result of a series of court decisions. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions began in 1881 as a federation of different unions that did not directly enroll workers. In 1886, it became known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL.

In Germany the Free Association of German Trade Unions was formed in 1897 after the conservative Anti-Socialist Laws of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck were repealed.

In France, labour organization was illegal until 1884. The Bourse du Travail was founded in 1887 and merged with the Fédération nationale des syndicats (National Federation of Trade Unions) in 1895 to form the General Confederation of Labour (France).

In a number of countries during the 20th century, including in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, legislation was passed to provide for the voluntary or statutory recognition of a union by an employer.

Prevalence worldwide

OECD

Union density

The prevalence of labor unions can be measured by "union density", which is expressed as a percentage of the total number of workers in a given location who are trade union members. The below table shows the percentage across OECD members.

| Country | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 13.7 | 14.7 | .. | .. | 24.9 |

| Austria | 26.3 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 36.9 |

| Belgium | 50.3 | 51.9 | 52.8 | 54.2 | 56.6 |

| Canada | 25.9 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 29.4 | 28.2 |

| Chile | 16.6 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 11.2 |

| Czech Republic | 11.5 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 27.2 |

| Denmark | 66.5 | 66.1 | 65.5 | 67.1 | 74.5 |

| Estonia | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 14.0 |

| Finland | 60.3 | 62.2 | 64.9 | 66.4 | 74.2 |

| France | 8.8 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.8 |

| Germany | 16.5 | 16.7 | 17.0 | 17.6 | 24.6 |

| Greece | .. | .. | 19.0 | .. | .. |

| Hungary | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 23.8 |

| Iceland | 91.8 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 89.1 |

| Ireland | 24.1 | 24.3 | 23.4 | 25.4 | 35.9 |

| Israel | .. | 25.0 | .. | .. | 37.7 |

| Italy | 34.4 | 34.3 | 34.4 | 35.7 | 34.8 |

| Japan | 17.0 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 21.5 |

| Korea | .. | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.4 |

| Latvia | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 12.6 | .. |

| Lithuania | 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.9 | .. |

| Luxembourg | 31.8 | 32.1 | 32.3 | 33.3 | .. |

| Mexico | 12.0 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 16.7 |

| Netherlands | 16.4 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 22.3 |

| New Zealand | .. | 17.3 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 22.4 |

| Norway | 49.2 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 53.6 |

| Poland | .. | .. | 12.7 | .. | 23.5 |

| Portugal | .. | .. | 15.3 | 16.1 | .. |

| Slovak Republic | .. | .. | 10.7 | 11.7 | 34.2 |

| Slovenia | .. | .. | 20.4 | 20.9 | 44.2 |

| Spain | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 17.5 |

| Sweden | 65.5 | 65.6 | 66.9 | 67.8 | 81.0 |

| Switzerland | 14.4 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 20.7 |

| Turkey | 9.2 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 12.5 |

| United Kingdom | 23.4 | 23.2 | 23.7 | 24.2 | 29.8 |

| United States | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 12.9 |

Source: OECD

The union density is especially high for Nordic countries with the average being 67% as of 2018.

Development

The union density has been steadily declining from the OECD average of 35.9% in 1998 to 27.9% in the year 2018.

The main reasons for these developments are a decline in manufacturing, increased globalization, and governmental policies.

The decline in manufacturing is the most direct one as it generally have been low- or unskilled workers who have benefited the most from labor unions. On the other hand, there might an increase in developing nations as OECD nations exported manufacturing industries to these markets. The second reason is globalization, which makes it harder for unions to maintain standards across countries. The last reason is governmental policies. These come from both sides of the political spectrum. In the UK and US, it has been mostly right-wing proposals that make it harder for unions to form or that limit their power. On the other side, there are many policies such as minimum wage, paid vacation, maternity/paternity leave, etc., that decrease the need to be in a union.

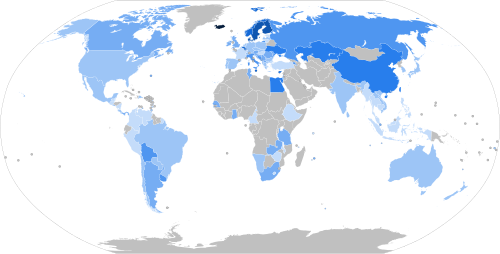

Worldwide

The prevalence of trade unions across the world is tracked by International Labor Organization. The data might differ from the ones provided by the OECD.

| Country | Year | Density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | 2013 | 13.3 |

| Argentina | 2014 | 27.7 |

| Armenia | 2015 | 32.2 |

| Australia | 2016 | 14.5 |

| Austria | 2016 | 26.9 |

| Belgium | 2018 | 65.0 |

| Belize | 2012 | 9.1 |

| Bermuda | 2012 | 23.0 |

| Bolivia | 2014 | 39.1 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2012 | 30.0 |

| Brazil | 2016 | 18.9 |

| Cambodia | 2012 | 9.6 |

| Cameroon | 2014 | 6.9 |

| Canada | 2016 | 28.4 |

| Chile | 2016 | 19.6 |

| China | 2015 | 44.9 |

| Colombia | 2016 | 9.5 |

| Costa Rica | 2016 | 19.4 |

| Croatia | 2016 | 25.8 |

| Cuba | 2008 | 81.4 |

| Cyprus | 2014 | 47.7 |

| Czech Republic | 2016 | 10.5 |

| Denmark | 2016 | 67.2 |

| Dominican Republic | 2015 | 11.0 |

| Egypt | 2012 | 43.2 |

| El Salvador | 2016 | 19.0 |

| Estonia | 2015 | 4.5 |

| Ethiopia | 2013 | 9.6 |

| Finland | 2016 | 64.6 |

| France | 2015 | 7.9 |

| Ghana | 2016 | 20.6 |

| Greece | 2016 | 18.6 |

| Guatemala | 2016 | 2.6 |

| Hong Kong | 2016 | 26.1 |

| Hungary | 2016 | 8.5 |

| Iceland | 2016 | 90.4 |

| India | 2011 | 12.8 |

| Indonesia | 2012 | 7.0 |

| Ireland | 2016 | 24.4 |

| Israel | 2016 | 28.0 |

| Italy | 2016 | 34.4 |

| Japan | 2016 | 17.3 |

| Kazakhstan | 2012 | 49.2 |

| Korea, Republic of | 2015 | 10.1 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 2010 | 15.5 |

| Latvia | 2015 | 12.6 |

| Lesotho | 2010 | 5.8 |

| Lithuania | 2016 | 7.7 |

| Luxembourg | 2016 | 32.0 |

| North Macedonia | 2010 | 28.0 |

| Malawi | 2013 | 5.5 |

| Malaysia | 2016 | 8.8 |

| Malta | 2015 | 51.4 |

| Mauritius | 2016 | 28.1 |

| Mexico | 2016 | 12.5 |

| Moldova, Republic of | 2016 | 23.9 |

| Montenegro | 2012 | 25.9 |

| Myanmar | 2015 | 1.0 |

| Namibia | 2016 | 17.5 |

| Netherlands | 2016 | 17.3 |

| New Zealand | 2015 | 17.9 |

| Niger | 2008 | 35.6 |

| Norway | 2015 | 52.5 |

| Pakistan | 2008 | 5.6 |

| Panama | 2016 | 11.9 |

| Paraguay | 2015 | 6.7 |

| Peru | 2016 | 5.7 |

| Philippines | 2014 | 8.7 |

| Poland | 2016 | 12.1 |

| Portugal | 2015 | 16.3 |

| Romania | 2013 | 25.2 |

| Russian Federation | 2015 | 30.5 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 2010 | 4.9 |

| Samoa | 2013 | 11.8 |

| Senegal | 2015 | 22.4 |

| Serbia | 2010 | 27.9 |

| Seychelles | 2011 | 2.1 |

| Sierra Leone | 2008 | 41.0 |

| Singapore | 2015 | 21.2 |

| Slovakia | 2014 | 12.0 |

| Slovenia | 2016 | 26.9 |

| South Africa | 2016 | 28.1 |

| Spain | 2015 | 13.9 |

| Sri Lanka | 2016 | 15.3 |

| Sweden | 2015 | 67.0 |

| Switzerland | 2015 | 15.7 |

| Taiwan, Republic of China | 2010 | 39.3 |

| Tanzania, United Republic of | 2015 | 24.3 |

| Thailand | 2016 | 3.5 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2013 | 19.8 |

| Tunisia | 2011 | 20.4 |

| Turkey | 2016 | 8.2 |

| Uganda | 2005 | 1.5 |

| Ukraine | 2015 | 43.8 |

| United Kingdom | 2016 | 23.5 |

| United States | 2016 | 10.3 |

| Vietnam | 2011 | 14.6 |

| Zambia | 2014 | 25.9 |

| Zimbabwe | 2010 | 7.5 |

Source: ILO

Trade unions by country

Australia

The Australian labour movement generally sought to end child labour practices, improve worker safety, increase wages for both union workers and non-union workers, raise the entire society's standard of living, reduce the hours in a work week, provide public education for children, and bring other benefits to working class families.

Melbourne Trades Hall was opened in 1859 with Trades and Labour Councils and Trades Halls opening in all cities and most regional towns in the next forty years. During the 1880s Trade unions developed among shearers, miners, and stevedores (wharf workers), but soon spread to cover almost all blue-collar jobs. Shortages of labour led to high wages for a prosperous skilled working class, whose unions demanded and got an eight-hour day and other benefits unheard of in Europe.

Australia gained a reputation as "the working man's paradise". Some employers tried to undercut the unions by importing Chinese labour. This produced a reaction which led to all the colonies restricting Chinese and other Asian immigration. This was the foundation of the White Australia Policy. The "Australian compact", based around centralised industrial arbitration, a degree of government assistance particularly for primary industries, and White Australia, was to continue for many years before gradually dissolving in the second half of the 20th century.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the growing trade union movement began a series of protests against foreign labour. Their arguments were that Asians and Chinese took jobs away from white men, worked for "substandard" wages, lowered working conditions and refused unionisation.

Objections to these arguments came largely from wealthy land owners in rural areas. It was argued that without Asiatics to work in the tropical areas of the Northern Territory and Queensland, the area would have to be abandoned.[37] Despite these objections to restricting immigration, between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies enacted legislation which excluded all further Chinese immigration. Asian immigrants already residing in the Australian colonies were not expelled and retained the same rights as their Anglo and Southern compatriots.

The Barton Government which came to power after the first elections to the Commonwealth parliament in 1901 was formed by the Protectionist Party with the support of the Australian Labor Party. The support of the Labor Party was contingent upon restricting non-white immigration, reflecting the attitudes of the Australian Workers Union and other labour organisations at the time, upon whose support the Labor Party was founded.

Belgium

With 65% of the workers belonging to a union, Belgium is a country with one of the highest percentages of trade union membership. Only the Scandinavian countries have a higher trade union density. The biggest union with around 1.7 million members is the Christian democrat Confederation of Christian Trade Unions (ACV-CSC) which was founded in 1904. The origins of the union can be traced back to the "Anti-Socialist Cotton Workers Union" that was founded in 1886. The second biggest union is the socialist General Federation of Belgian Labour (ABVV-FGTB) which has a membership of more than 1.5 million. The ABVV-FGTB traces its origins to 1857, when the first Belgian union was founded in Ghent by a group of weavers. This and other socialist unions became unified around 1898. The ABVV-FGTB in its current form dates back to 1945. The third major multi-sector union in Belgium is the liberal (classical liberal) union General Confederation of Liberal Trade Unions of Belgium (ACLVB-CGSLB) which is relatively small in comparison to the first two with a little under 290 thousand members. The ACLVB-CGSLB was founded in 1920 in an effort to unite the many small liberal unions. Back then the liberal union was known as the "Nationale Centrale der Liberale Vakbonden van België". In 1930, the ACLVB-CGSLB adopted its current name.

Besides these "big three" there are a number of smaller unions, some more influential than others. These smaller unions tend to specialize in one profession or economic sector. Next to these specialized unions there is also the Neutral and Independent Union that rejects the pillarization of the "big three" trade unions (their affiliation with political parties). There is also a small Flemish nationalist union that exists only in the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium, called the Vlaamse Solidaire Vakbond. The last Belgian union worth mentioning is the very small, but highly active anarchist union called the Vrije Bond.

Canada

Canada's first trade union, the Labourers' Benevolent Association (now International Longshoremen's Association Local 273), formed in Saint John, New Brunswick in 1849. The union was formed when Saint John's longshoremen banded together to lobby for regular pay and a shorter workday. Canadian unionism had early ties with Britain and Ireland. Tradesmen who came from Britain brought traditions of the British trade union movement, and many British unions had branches in Canada. Canadian unionism's ties with the United States eventually replaced those with Britain.

Collective bargaining was first recognized in 1945, after the strike by the United Auto Workers at the General Motors' plant in Oshawa, Ontario. Justice Ivan Rand issued a landmark legal decision after the strike in Windsor, Ontario, involving 17,000 Ford workers. He granted the union the compulsory check-off of union dues. Rand ruled that all workers in a bargaining unit benefit from a union-negotiated contract. Therefore, he reasoned they must pay union dues, although they do not have to join the union.

The post-World War II era also saw an increased pattern of unionization in the public service. Teachers, nurses, social workers, professors and cultural workers (those employed in museums, orchestras and art galleries) all sought private-sector collective bargaining rights. The Canadian Labour Congress was founded in 1956 as the national trade union center for Canada.

In the 1970s the federal government came under intense pressures to curtail labour cost and inflation. In 1975, the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau introduced mandatory price and wage controls. Under the new law, wages increases were monitored and those ruled to be unacceptably high were rolled back by the government.

Pressures on unions continued into the 1980s and '90s. Private sector unions faced plant closures in many manufacturing industries and demands to reduce wages and increase productivity. Public sector unions came under attack by federal and provincial governments as they attempted to reduce spending, reduce taxes and balance budgets. Legislation was introduced in many jurisdictions reversing union collective bargaining rights, and many jobs were lost to contractors.

Prominent domestic unions in Canada include ACTRA, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, the Canadian Union of Public Employees, the Public Service Alliance of Canada, the National Union of Public and General Employees, and Unifor. International unions active in Canada include the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, United Automobile Workers, United Food and Commercial Workers, and United Steelworkers.

Colombia

Until around 1990 Colombian trade unions were among the strongest in Latin America. However, the 1980s expansion of paramilitarism in Colombia saw trade union leaders and members increasingly targeted for assassination, and as a result Colombia has been the most dangerous country in the world for trade unionists for several decades. Between 2000 and 2010 Colombia accounted for 63.1% of trade unionists murdered globally. According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) there were 2832 murders of trade unionists between 1 January 1986 and 30 April 2010, meaning that "on average, men and women trade unionists in Colombia have been killed at the rate of one every three days over the last 23 years."

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, trade unions first appeared in the late 1800s to support workers in a variety of urban and industrial jobs, such as railroad builders and craft tradesmen. After facing violent repression, such as during the 1934 United Fruit Strike, unions gained more power after the 1948 Costa Rican Civil War. Today, Costa Rican unions are strongest in the public sector, including the fields of education and medicine, but also have a strong presence in the agricultural sector. In general, Costa Rican unions support government regulation of the banking, medical, and education fields, as well as improved wages and working conditions.

Germany

Trade unions in Germany have a history reaching back to the German revolution in 1848, and still play an important role in the German economy and society. In 1875 the SPD, the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which is one of the biggest political parties in Germany, at first supported the forming of unions in Germany. However, according to John A. Moses, the German trade unions were not directly affiliated with the Social Democratic Party. The SPD leadership insisted on the primacy of politics, and refused to emphasize support for union goals and methods. The unions led Carl Legien (1861-1920) developed their own nonpartisan political goals.

In the early 1930s, according to Gerard Braunthal, the three main trade unions (Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, Allgemeiner freier Angestelltenbund, and Allgemeiner Deutscher Beamtenbund) failed to actively oppose Hitler in 1932–33. They minimized the threat in 1932 and opposed a general strike because it might spark a civil war. As the Nazis took power in 1933, the high unemployment had demoralized workers. Their historic faith in socialism gave way to a wave of nationalism. The leaders did not foresee how the Nazis would completely unseat them and suppress labor's aspirations.

The most important labour organisation is the German Confederation of Trade Unions (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund – DGB), which represents more than 6 million workers in 2011. It is the umbrella association of several single trade unions for special economic sectors. The DGB is not the only Union Organization that represents the working trade. There are smaller organizations, such as the CGB, which is a Christian-based confederation, that represent over 1.5 million workers.

India

In India, the Trade Union movement is generally divided on political lines. According to provisional statistics from the Ministry of Labour, trade unions had a combined membership of 24,601,589 in 2002. As of 2008, there are 12 Central Trade Union Organisations (CTUO) recognized by the Ministry of Labour. The forming of these unions was a big deal in India. It led to a big push for more regulatory laws which gave workers a lot more power.

AITUC is the oldest trade union in India. It is a left supported organization. A trade union with nearly 2,000,000 members is the Self Employed Women's Association (SEWA) which protects the rights of Indian women working in the informal economy. In addition to the protection of rights, SEWA educates, mobilizes, finances, and exalts their members' trades. Multiple other organizations represent workers. These organizations are formed upon different political groups. These different groups allow different groups of people with different political views to join a Union.

Japan

Trade unions emerged in Japan in the second half of the Meiji period as the country underwent a period of rapid industrialization. Until 1945, however, the labour movement remained weak, impeded by lack of legal rights, anti-union legislation, management-organised factory councils, and political divisions between "cooperative" and radical unionists. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the US Occupation authorities initially encouraged the formation of independent unions. Legislation was passed that enshrined the right to organise, and membership rapidly rose to 5 million by February 1947. The organisation rate, however, peaked at 55.8% in 1949 and subsequently declined to 18.2% (2006). The labour movement went through a process of reorganisation from 1987 to 1991 from which emerged the present configuration of three major trade union federations, Rengo, Zenroren, and Zenrokyo, along with other smaller national union organisations.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia

In the three Baltic countries the independent trade unions was an aspect of almost every worker's life during the period of Soviet rule from 1944 to 1991. The trade union system was closely integrated with that of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After the regaining of national independence in 1990–1991 the trade unions in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia have experienced rapid loss of membership and economic power, while employers' organisations have increased both in power and membership. Low financial and organisational capacity caused by declining membership adds to the problem of interest definition, aggregation and protection in negotiations with employers' and state organisations. Even the difference exists in the way of organization trade union and density. Starting from 2008 the union density slightly decrease in Latvia and Lithuania. In case of Estonia this indicator is lower than in Latvia and Lithuania but stays stable average 7 percent from total number of employment. Historical legitimacy is one of the negative factors that determine low associational power.

Mexico

Before the 1990s, unions in Mexico had been historically part of a state institutional system. From 1940 until the 1980s, during the worldwide spread of neoliberalism through the Washington Consensus, the Mexican unions did not operate independently, but instead as part of a state institutional system, largely controlled by the ruling party.

During these 40 years, the primary aim of the trade unions was not to benefit the workers, but to carry out the state's economic policy under their cosy relationship with the ruling party. This economic policy, which peaked in the 1950s and 60s with the so-called "Mexican Miracle", saw rising incomes and improved standards of living but the primary beneficiaries were the wealthy.

In the 1980s, Mexico began adhering to Washington Consensus policies, selling off state industries such as railroad and telecommunications to private industries. The new owners had an antagonistic attitude towards unions, which, accustomed to comfortable relationships with the state, were not prepared to fight back. A movement of new unions began to emerge under a more independent model, while the former institutionalized unions had become very corrupt, violent, and led by gangsters. From the 1990s onwards, this new model of independent unions prevailed, a number of them represented by the National Union of Workers / Unión Nacional de Trabajadores.

Current old institutions like the Oil Workers Union and the National Education Workers' Union (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, or SNTE) are examples of how the use of government benefits are not being applied to improve the quality in the investigation of the use of oil or the basic education in Mexico as long as their leaders show publicly that they are living wealthily. With 1.4 million members, the teachers' union is Latin America's largest; half of Mexico's government employees are teachers. It controls school curriculums, and all teacher appointments. Until recently, retiring teachers routinely "gave" their lifelong appointment to a relative or "sell" it for anywhere in between $4,700 and $11,800.

In 2022, Sindicato independiente nacional de trabajadores trabajadoras de la industria automotriz, SINTTIA, a union backed by American and Canadian unions won a union representation election at a General Motors plant in the city of Silao. The Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM), a union affiliated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which had negotiated sweet-heart contracts with GM since the opening of the plant in 1995, and an allied "independent" union received only small percentages of the vote. A worker at the plant with 10 years service reported wages of 480 pesos ($23.27) for a 12-hour shift. At Volkswagen's plant in Puebla state, the union has negotiated average pay of 600 pesos ($29.15) a day for an eight-hour shift.

Nordic countries

Trade unions (Danish: Fagforeninger, Norwegian: Fagforeninger/Fagforeiningar, Swedish: Fackföreningar, Finnish: Ammattiliitot) have a long tradition in Scandinavian and Nordic society. Beginning in the mid-19th century, they today have a large impact on the nature of employment and workers' rights in many of the Nordic countries. One of the largest trade unions in Sweden is the Swedish Confederation of Trade Unions, (LO, Landsorganisationen), incorporating unions such as the Swedish Metal Workers' Union (IF Metall = Industrifacket Metall), the Swedish Electricians' Union (Svenska Elektrikerförbundet) and the Swedish Municipality Workers' Union (Svenska Kommunalarbetareförbundet, abbreviated Kommunal). One of the aims of IF Metall is to transform jobs into "good jobs", also called "developing jobs". Swedish system is strongly based on the so-called Swedish model, which argues the importance of collective agreements between trade unions and employers.

Today, the world's highest rates of union membership are in the Nordic countries. As of 2018 or latest year, the percentage of workers belonging to a union (trade union density) was 90.4% in Iceland, 67.2% in Denmark, 66.1% in Sweden, 64.4% in Finland and 52.5% in Norway, while it is unknown in Greenland, Faroe Islands and Åland. Excluding full-time students working part-time, Swedish union density was 68% in 2019. In all the Nordic countries with a Ghent system—Sweden, Denmark and Finland—union density is about 70%. The considerably raised membership fees of Swedish union unemployment funds implemented by the new center-right government in January 2007 caused large drops in membership in both unemployment funds and trade unions. From 2006 to 2008, union density declined by six percentage points: from 77% to 71%.

Spain

During the Spanish civil war anarchists, and syndicalists took control over much of Spain. Implementing worker control through a system of libertarian socialism with organizations like the anarcho-syndicalist CNT organizing throughout Spain. Unions were particularly present in Revolutionary Catalonia, in which anarchists were already the basis for most of society with over 90% of industries being organized through work cooperatives. The republicans, anarchists and leftists would later lose control over Spain, with Francisco Franco becoming dictator of Spain.

During the fascist regime of Spain the Francoist regime saw the worker movement and union movement as a threat, Franco banned all existing trade unions and set up the government controlled Spanish Syndical Organization as the only legal Spanish trade union, with the organization existing to maintain Franco's power.

Many anarchists, communists and leftists turned towards insurgent tactics as Franco implemented wide reaching authoritarian policies, with the CNT and other unions being forced underground. Anarchists would operate covertly setting up local organizations and underground movements to challenge Franco. On the 20 of December the ETA assassinated Luis Carrero. The death of Carrero Blanco had numerous political implications. By the end of 1973, the physical health of Francisco Franco had declined significantly, and it epitomized the final crisis of the Francoist regime. After his death, the most conservative sector of the Francoist State, known as the búnker, wanted to influence Franco so that he would choose an ultraconservative as Prime Minister. Finally, he chose Carlos Arias Navarro, who originally announced a partial relaxation of the most rigid aspects of the Francoist State, but quickly retreated under pressure from the búnker. After Franco's death Arias Navarro began relaxing Spanish authoritarianism.

During the Spanish transition to democracy, leftist organizations became legal once again. In modern Spain trade unions now contribute massively towards Spanish society, being again the main catalyst for political change in Spain, with cooperatives employing large parts of the Spanish population such as the Mondragon Corporation. Trade unions today lead mass protests against the Spanish government, and are one of the main vectors of political change.

United Kingdom

Moderate New Model Unions dominated the union movement from the mid-19th century and where trade unionism was stronger than the political labour movement until the formation and growth of the Labour Party in the early years of the 20th century.

Trade unionism in the United Kingdom was a major factor in some of the economic crises during the 1960s and the 1970s, culminating in the "Winter of Discontent" of late-1978 and early-1979, when a significant percentage of the nation's public sector workers went on strike. By this stage, some 12,000,000 workers in the United Kingdom were trade union members. However, the election victory of the Conservative Party led by Margaret Thatcher at the 1979 general election, at the expense of Labour's James Callaghan, saw substantial trade union reform which saw the level of strikes fall. The level of trade union membership also fell sharply in the 1980s, and continued falling for most of the 1990s. The long decline of most of the industries in which manual trade unions were strong—e.g. steel, coal, printing, the docks—was one of the causes of this loss of trade union members.

In 2011, there were 6,135,126 members in TUC-affiliated unions, down from a peak of 12,172,508 in 1980. Trade union density was 14.1% in the private sector and 56.5% in the public sector.

United States

Labor unions are legally recognized as representatives of workers in many industries in the United States. In the United States, unions were formed based on power with the people, not over the people like the government at the time. Their activity today centres on collective bargaining over wages, benefits and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and supporting endorsed candidates at the state and federal level.

Most unions in America are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL–CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL–CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.

In 2010, the percentage of workers belonging to a union in the United States (or total labor union "density") was 11.4%, compared to 18.3% in Japan, 27.5% in Canada and 70% in Finland.

The most prominent unions are among public sector employees such as teachers, police and other non-managerial or non-executive federal, state, county and municipal employees. Members of unions are disproportionately older, male and residents of the Northeast, the Midwest, and California.

The majority of union members come from the public sector. Nearly 34.8% of public sector employees are union members. In the private sector, just 6.3% of employees are union members—levels not seen since 1932.

Union workers in the private sector average 10–30% higher pay than non-union in America after controlling for individual, job, and labour market characteristics. Because of their inherently governmental function, public sector workers are paid the same regardless of union affiliation or non-affiliation after controlling for individual, job, and labour market characteristics.

Vatican (Holy See)

The Association of Vatican Lay Workers represents lay employees in the Vatican.

Structure and politics

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled workers (craft unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US), a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, the UK and the US), or attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism, found in Australia, Canada, Germany, Finland, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US). These unions are often divided into "locals", and united in national federations. These federations themselves will affiliate with Internationals, such as the International Trade Union Confederation. However, in Japan, union organization is slightly different due to the presence of enterprise unions, i.e. unions that are specific to a plant or company. These enterprise unions, however, join industry-wide federations which in turn are members of Rengo, the Japanese national trade union confederation.

In Western Europe, professional associations often carry out the functions of a trade union. In these cases, they may be negotiating for white-collar or professional workers, such as physicians, engineers or teachers. Typically such trade unions refrain from politics or pursue a more liberal politics than their blue-collar counterparts.

A union may acquire the status of a "juristic person" (an artificial legal entity), with a mandate to negotiate with employers for the workers it represents. In such cases, unions have certain legal rights, most importantly the right to engage in collective bargaining with the employer (or employers) over wages, working hours, and other terms and conditions of employment. The inability of the parties to reach an agreement may lead to industrial action, culminating in either strike action or management lockout, or binding arbitration. In extreme cases, violent or illegal activities may develop around these events.

In other circumstances, unions may not have the legal right to represent workers, or the right may be in question. This lack of status can range from non-recognition of a union to political or criminal prosecution of union activists and members, with many cases of violence and deaths having been recorded historically.

Unions may also engage in broader political or social struggle. Social Unionism encompasses many unions that use their organizational strength to advocate for social policies and legislation favourable to their members or to workers in general. As well, unions in some countries are closely aligned with political parties.

Unions are also delineated by the service model and the organizing model. The service model union focuses more on maintaining worker rights, providing services, and resolving disputes. Alternately, the organizing model typically involves full-time union organizers, who work by building up confidence, strong networks, and leaders within the workforce; and confrontational campaigns involving large numbers of union members. Many unions are a blend of these two philosophies, and the definitions of the models themselves are still debated.

In Britain, the perceived left-leaning nature of trade unions has resulted in the formation of a reactionary right-wing trade union called Solidarity which is supported by the far-right BNP. In Denmark, there are some newer apolitical "discount" unions who offer a very basic level of services, as opposed to the dominating Danish pattern of extensive services and organizing.

In contrast, in several European countries (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland), religious unions have existed for decades. These unions typically distanced themselves from some of the doctrines of orthodox Marxism, such as the preference of atheism and from rhetoric suggesting that employees' interests always are in conflict with those of employers. Some of these Christian unions have had some ties to centrist or conservative political movements and some do not regard strikes as acceptable political means for achieving employees' goals. In Poland, the biggest trade union Solidarity emerged as an anti-communist movement with religious nationalist overtones and today it supports the right-wing Law and Justice party.

Although their political structure and autonomy varies widely, union leaderships are usually formed through democratic elections. Some research, such as that conducted by the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training, argues that unionized workers enjoy better conditions and wages than those who are not unionized.

Shop types

Companies that employ workers with a union generally operate on one of several models:

- A closed shop (US) or a "pre-entry closed shop" (UK) employs only people who are already union members. The compulsory hiring hall is an example of a closed shop—in this case the employer must recruit directly from the union, as well as the employee working strictly for unionized employers.

- A union shop (US) or a "post-entry closed shop" (UK) employs non-union workers as well, but sets a time limit within which new employees must join a union.

- An agency shop requires non-union workers to pay a fee to the union for its services in negotiating their contract. This is sometimes called the Rand formula.

- An open shop does not require union membership in employing or keeping workers. Where a union is active, workers who do not contribute to a union may include those who approve of the union contract (free riders) and those who do not. In the United States, state level right-to-work laws mandate the open shop in some states. In Germany only open shops are legal; that is, all discrimination based on union membership is forbidden. This affects the function and services of the union.

An EU case concerning Italy stated that, "The principle of trade union freedom in the Italian system implies recognition of the right of the individual not to belong to any trade union ("negative" freedom of association/trade union freedom), and the unlawfulness of discrimination liable to cause harm to non-unionized employees."

In Britain, previous to this EU jurisprudence, a series of laws introduced during the 1980s by Margaret Thatcher's government restricted closed and union shops. All agreements requiring a worker to join a union are now illegal. In the United States, the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 outlawed the closed shop.

In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights found Danish closed-shop agreements to be in breach of Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It was stressed that Denmark and Iceland were among a limited number of contracting states that continue to permit the conclusion of closed-shop agreements.

Diversity of international unions

Union law varies from country to country, as does the function of unions. For example, German and Dutch unions have played a greater role in management decisions through participation in corporate boards and co-determination than have unions in the United States. Moreover, in the United States, collective bargaining is most commonly undertaken by unions directly with employers, whereas in Austria, Denmark, Germany or Sweden, unions most often negotiate with employers associations.

Concerning labour market regulation in the EU, Gold (1993) and Hall (1994) have identified three distinct systems of labour market regulation, which also influence the role that unions play:

- "In the Continental European System of labour market regulation, the government plays an important role as there is a strong legislative core of employee rights, which provides the basis for agreements as well as a framework for discord between unions on one side and employers or employers' associations on the other. This model was said to be found in EU core countries such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, and it is also mirrored and emulated to some extent in the institutions of the EU, due to the relative weight that these countries had in the EU until the EU expansion by the inclusion of 10 new Eastern European member states in 2004.

- In the Anglo-Saxon System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is much more limited, which allows for more issues to be decided between employers and employees and any union or employers' associations which might represent these parties in the decision-making process. However, in these countries, collective agreements are not widespread; only a few businesses and a few sectors of the economy have a strong tradition of finding collective solutions in labour relations. Ireland and the UK belong to this category, and in contrast to the EU core countries above, these countries first joined the EU in 1973.

- In the Nordic System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is limited in the same way as in the Anglo-Saxon system. However, in contrast to the countries in the Anglo-Saxon system category, this is a much more widespread network of collective agreements, which covers most industries and most firms. This model was said to encompass Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Here, Denmark joined the EU in 1973, whereas Finland and Sweden joined in 1995."

The United States takes a more laissez-faire approach, setting some minimum standards but leaving most workers' wages and benefits to collective bargaining and market forces. Thus, it comes closest to the above Anglo-Saxon model. Also, the Eastern European countries that have recently entered into the EU come closest to the Anglo-Saxon model.

In contrast, in Germany, the relation between individual employees and employers is considered to be asymmetrical. In consequence, many working conditions are not negotiable due to a strong legal protection of individuals. However, the German flavor or works legislation has as its main objective to create a balance of power between employees organized in unions and employers organized in employers associations. This allows much wider legal boundaries for collective bargaining, compared to the narrow boundaries for individual negotiations. As a condition to obtain the legal status of a trade union, employee associations need to prove that their leverage is strong enough to serve as a counterforce in negotiations with employers. If such an employees association is competing against another union, its leverage may be questioned by unions and then evaluated in a court trial. In Germany, only very few professional associations obtained the right to negotiate salaries and working conditions for their members, notably the medical doctors association Marburger Bund and the pilots association Vereinigung Cockpit. The engineers association Verein Deutscher Ingenieure does not strive to act as a union, as it also represents the interests of engineering businesses.

Beyond the classification listed above, unions' relations with political parties vary. In many countries unions are tightly bonded, or even share leadership, with a political party intended to represent the interests of the working class. Typically this is a left-wing, socialist, or social democratic party, but many exceptions exist, including some of the aforementioned Christian unions. In the United States, trade unions are almost always aligned with the Democratic Party with a few exceptions. For example, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters has supported Republican Party candidates on a number of occasions and the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) endorsed Ronald Reagan in 1980. In Britain trade union movement's relationship with the Labour Party frayed as party leadership embarked on privatization plans at odds with what unions see as the worker's interests. However, it has strengthened once more after the Labour party's election of Ed Miliband, who beat his brother David Miliband to become leader of the party after Ed secured the trade union votes. Additionally, in the past, there was a group known as the Conservative Trade Unionists, or CTU, formed of people who sympathized with right wing Tory policy but were Trade Unionists.

Historically, the Republic of Korea has regulated collective bargaining by requiring employers to participate, but collective bargaining has only been legal if held in sessions before the lunar new year.

International unionization

The oldest global trade union organizations include the World Federation of Trade Unions created in 1945.

The largest trade union federation in the world is the Brussels-based International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), created in 2006, which has approximately 309 affiliated organizations in 156 countries and territories, with a combined membership of 166 million. The ITUC is a federation of national trade union centres, such as the AFL-CIO in the United States and the Trades Union Congress in the United Kingdom.

National and regional trade unions organizing in specific industry sectors or occupational groups also form global union federations, such as Union Network International, the International Transport Workers Federation, the International Federation of Journalists, the International Arts and Entertainment Alliance or Public Services International.

Impact

Economics

The academic literature shows substantial evidence that labor unions reduce economic inequality. The economist Joseph Stiglitz has asserted that, "Strong unions have helped to reduce inequality, whereas weaker unions have made it easier for CEOs, sometimes working with market forces that they have helped shape, to increase it." The decline in unionization since the Second World War in the United States has been associated with a pronounced rise in income and wealth inequality and, since 1967, with loss of middle class income. Right-to-work laws have been linked to greater economic inequality in the United States.

Research from Norway has found that high unionization rates lead to substantial increases in firm productivity, as well as increases in workers' wages. Research from Belgium also found productivity gains, although smaller. Other research in the United States has found that unions can harm profitability, employment and business growth rates. Research from the Anglosphere indicates that unions can provide wage premiums and reduce inequality while reducing employment growth and restricting employment flexibility.

In the United States, the outsourcing of labour to Asia, Latin America, and Africa has been partially driven by increasing costs of union partnership, which gives other countries a comparative advantage in labour, making it more efficient to perform labour-intensive work there. Trade unions have been accused of benefiting insider workers and those with secure jobs at the cost of outsider workers, consumers of the goods or services produced, and the shareholders of the unionized business. Milton Friedman, economist and advocate of laissez-faire capitalism, sought to show that unionization produces higher wages (for the union members) at the expense of fewer jobs, and that, if some industries are unionized while others are not, wages will tend to decline in non-unionized industries.

Politics

In the United States, the weakening of unions has been linked to more favorable electoral outcomes for the Republican Party. Legislators in areas with high unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the poor, whereas areas with lower unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the rich. Higher unionization rates increase the likelihood of parental leave policies being adopted. Republican-controlled states are less likely to adopt more restrictive labor policies when unions are strong in the state.

Research in the United States found that American congressional representatives were more responsive to the interests of the poor in districts with higher unionization rates. Another 2020 American study found an association between US state level adoption of parental leave legislation and labor union strength.

In the United States, unions have been linked to lower racial resentment among whites. Membership in unions increases political knowledge, in particular among those with less formal education.

Health

In the United States, higher union density has been associated with lower suicide/overdose deaths. Decreased unionization rates in the United States have been linked to an increase in occupational fatalities.

Union publications

Several sources of current news exist about the trade union movement in the world. These include LabourStart and the official website of the international trade union movement Global Unions. A source of international news about unions is RadioLabour which provides daily (Monday to Friday) news reports.

Labor Notes is the largest circulation cross-union publication remaining in the United States. It reports news and analysis about union activity or problems facing the labour movement. Another source of union news is the Workers Independent News, a news organization providing radio articles to independent and syndicated radio shows in the United States.